BLIND SPOTS

ON A DELHI PLAYGROUND in the late 2000s, five-year-old Azania was about to kick a football with her white canvas shoes, when a boy from the rival team screamed, “Get away from the ball, you Paki.” When the author Nazia Erum heard about this—one of several instances of Islamophobia in elite schools in the National Capital Region, she writes—she wondered whether she should give her own daughter a Muslim name. When did schools become like this? She remembered that her elder brother was called “Hamas” in the 1990s, but that had felt somewhat lighthearted by comparison.

A few years before the playground incident, another child in a different part of the city found that there was an unexpected problem with her new home. After moving near her workplace in a Muslim-dominated locality near Jamia Millia Islamia, the author Rakhshanda Jalil sent handmade cards to her daughter’s classmates to invite them home for her birthday. Most of her daughter’s friends declined the invitation. Over the phone, their mothers explained to Jalil what had changed. It was different when Jalil lived in Gulmohar Park, an elite outpost where Muslims are not conspicuous, they said, but “we have no idea about the Jamia side.”

In 2008, after night-time discounts for phone calls kicked in, the writer Neyaz Farooquee and his friends used to spend hours gossiping and mocking each other. They spoke about the women they were interested in, college life, and their friend Kafil’s obsession with trivia regarding guns and weapons. Days after the Batla House encounter in September that year, Farooquee deleted the numbers of his closest friends from his phone.

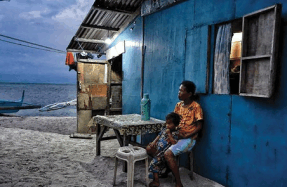

After the 1992 Mumbai riots, when Sumaiya’s family moved to the ghetto of Mumbra in Mumbai, her parents could not arrange for her to go to school. She had to drop out. In this new place, water and electricity were always in short supply, and there was garbage everywhere.

Things were not the same anymore.

A good deal of Muslim autobiographical writing in India seems to hinge on two points: a remembered past, and a present that is worse and more difficult in myriad ways. The sense of an escalating decline is ubiquitous, but the patterns signifying that something has been lost are less linear than they may initially seem. All Muslims did not inhabit the same havens to begin with.

There is a certain way in which “Muslim memoirs” are written and reviewed. The years of a writer’s life are often charted against depleting levels of secularism in the country. A few themes make frequent appearances: the pain surrounding Partition and a sense of disbelief that the Congress let it happen; the ostensible glory of the Nehruvian era—the 1960s and 1970s—when Muslims could do their jobs without being made aware of their religion, and how this started changing; the ulemas of the 1980s, who stymied attempts to reform the community and change antiquated personal laws; and the gradual institutional collapse of secularism after the demolition of the Babri Masjid in 1992. But is there more to Muslim lives in India that this arc obfuscates?

A wave of recent non-fiction books use the autobiographical form to tell the story of Muslims in India. Published in the last few years, faced with an escalating assault on Muslims under the Narendra Modi government, these writings provide an insight into Muslims’ minds as they witness these times. The writers contextualise their experiences against the broader history of independent India. In her book , Nazia Erum, faced with bringing up her daughter in an Islamophobic world, describes her conversations with other Muslim parents. Neyaz Farooquue, in , takes us into the petrified mind of a young Muslim man who fears, responds to the stereotypes she faces. Seema Mustafa’s and Saeed Naqvi’s compare the authors’ experiences of growing up in a secular, pluralist India to what they later witnessed as journalists reporting on events that reveal the erosion of the India they once knew.

You’re reading a preview, subscribe to read more.

Start your free 30 days