Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

Transportation

Enviado por

Armil Busico PuspusDescrição original:

Direitos autorais

Formatos disponíveis

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Transportation

Enviado por

Armil Busico PuspusDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

TRANSPORTATION & PUBLIC SERVICE LAW Prof. Benjamin A. Cabrido Jr.

USJ-R College of Law Chapter 1 GENERAL CONCEPTS IN TRANSPORTATION LAW Contract of Transportation There is contract of transportation where a person obligates himself to transport persons or property from one place to another for a consideration. The contract may therefore involve carriage of passengers or carriage of goods. The person who obligates himself to transport the goods or passengers may be a common carrier or a private carrier. Parties in a contract of carriage Passenger one who travels in a public conveyance by virtue of contract, express or implied, with the carrier as to the payment of fare or that which is accepted as an equivalent thereof (Nueca v. Manila Railroad Co., G.R. 31731-R, Jan. 30, 1968) Common Carrier one that holds itself out as ready to engage in the transportation of goods for hire as a public employment and not as a casual occupation. (De Guzman v. CA, G.R. L-47822, Dec. 22, 1988) Baliwag Transit v. CA, G.R. 80447, Jan. 31, 1989 Facts: The parents of George, who is already of legal age filed a case against Baliwag for breach of contract alleging that because of the negligent manner by its driver, George was thrown off the bus as a result of which the latter sustained multiple serious physical injuries. His parents was seeking reimbursement of their medical expenses and other incidental expenses incurred by them due to hospitalization of George. While the case was pending, George signed a waiver of claim in favor of Baliwags insurer, Fortune Insurance. Ruling: Since the suit is one for breach of contract of carriage, the release of claims executed by Georg, as the injured party, discharging Fortune Insurance and Baliwag from any and all liability is valid. is valid. Significantly, the contact of carriage was actually between George, as the paying passenger, and Baliwag, as the common carrier. x x x x Since the contract may be violated only by the parties thereto, as against each other, in an action upon that contract, the real parties in interest, either as plaintiff or as defendant, must be parties to said contract. In the absence of any contract of carriage between Baliwag and Georges parents, the latter are not real parties in interest in an action for breach of that contract. Parties in Carriage of Goods Shipper is the person who delivers the goods to the carrier for transportation. He is the person who pays the consideration or on whose behalf payment is made. Consignee is the person to whom the goods are to be delivered. The consignee may be the shipper himself or a third person who is not actually party to the contract. Carrier (Ibid) Everett Steamship Corp. v. CA G.R. 122494, Oct. 8, 1998

Facts: Hernandez Trading imported three crates of bus spare parts from Japan. The crates were shipped onboard "ADELFAEVERETTE," a vessel owned by petitioner's principal, Everett Orient Lines. Upon arrival at the port of Manila, it was discovered that one of the crates was missing. The loss was confirmed and admitted by Everett. .. However, Everett offered to pay only One Hundred Thousand (Y100,000.00) Yen, the maximum amount stipulated under Clause 18 of the covering bill of lading which limits the liability of petitioner. Hernandez rejected. The trial found in favor of Hernandez. On appeal, Everett argued that consent of the consignee to the terms and conditions of the bill of lading is necessary to make such stipulations binding upon it. Ruling: When Hernandez formally claimed reimbursement for the missing goods from Everett and subsequently filed a case against the it based on the very same bill of lading, it accepted the provisions of the contract and thereby made itself a party thereto, or at least has come to court to enforce it. However, the liability of the carrier under the limited liability clause stands, which is limited to One Hundred Thousand (Y100,000.00) Yen. Perfection of Contract involving Carriage In General If contract to carry, i.e. an agreement to carry the passenger at some future date, perfection takes place upon mere consent since such contract is consensual in nature. If contract of carriage, which is a real contract, perfection takes place when the carrier is actually used and the latter has assumed its obligation as a carrier. Specific Perfections of Contract of Carriage: AIRCRAFT If contract to carry, there is perfection even if no tickets have been issued provided there was meeting of minds with respect to the subject matter and the consideration. If contract of carriage, there is perfection if it was established that the passenger had CHECKED IN at the departure counter, passed through customs and immigration, boarded the shuttle bus and proceeded to the ramp of the aircraft. Specific Perfections of Contract of Carriage: BUSES, JEEPNEYS, STREET CARS Once the bus or jeepney stops, it is in effect making a continuous offer to the passengers. Hence, it is the duty of the driver to stop their conveyances for a reasonable length of time in order to afford passengers an opportunity to board and enter. If passenger is injured upon boarding, liability based on contract of carriage already attaches to the common carrier since the passenger was deemed to be accepting the offer when he attempted to board. The contract is perfected from that precise moment. Specific Perfections of Contract of Carriage: TRAINS

Perfection takes place when a person, with bona fide intention to use the facilities of the carrier and possessing sufficient fare with which to pay for his passage, has presented himself to the carrier for transportation in the place and manner that he will be transported. Where a person has already purchased a LRT token and while waiting on the platform designated for boarding fell thereon and hit by the train, he was deemed a passenger. British Airways v. CA, G.R. 92288, Feb. 9, 1993 Facts: On two occasions, private respondent recruitment agency was not able to send its workers to Saudi Arabia despite the fact that its principal there had already purchased pre-paid tickets because petitioners computers broke down. Private respondent thereafter filed a case on breach of contract of carriage. Petitioner argued that there was no perfected contract. Ruling: Petitioner's repeated failures to transport private respondent's workers in its flight despite confirmed booking of said workers clearly constitutes breach of contract and bad faith on its part. There is no dispute as to the Petitioners consent to the said contract "to carry" its contract workers from Manila to Jeddah. The appellant's consent thereto, on the other hand, was manifested by its acceptance of the PTA or prepaid ticket advice that ROLACO Engineering has prepaid the airfares of the Petitioner's contract workers advising the appellant that it must transport the contract workers on or before the end of March, 1981 and the other batch in June, 1981. Accordingly, there could be no more pretensions as to the existence of an oral contract of carriage imposing reciprocal obligations on both parties. Common Carrier Defined Art. 1732. Common carriers are persons, corporation, firms or associations engaged in the business of carrying or transporting passengers or good or both by land, water, or air, for compensation, offering their services to the public. A common carrier is also defined as one that holds itself out as ready to engage in the transportation of goods for hire as a public employment and not as a casual occupation, (De Guzman v. CA, G.R. L-47822, Dec. 22, 1988) Concept of Common Carrier analogous to Public Service Public Service includes every person that now or hereafter may own, operate, manage, or control int he Philippines, for hire or compensation, with general or limited clientele, whether permanent, occasional or accidental. Done for general business purposes, any common carrier, railroad, street railway, traction railway, subway motor vehicle, either for freight or passenger, or both, with or without fixed route. ..

Whatever may be its classification, freight or carrier service of any class, express service, steamboat, or steamship line, pontines, ferries and water craft. Engaged in the transportation of passengers or freight or both, shipyard, marine repair shop, wharf or dock, ice plant, ice-refrigeration plant, canal, irrigation system, gas, electric light, heat and power, water supply and power petroleum, sewerage system, wire or wireless communications systems, wire or wireless broadcasting stations and other similar public services. Sorita v. Public Service Commission, G.R. L-20965, Oct. 29, 1966 Held: In drawing the line between "steamboats, motorships, and steamship lines" on one side and pontines, ferries, and water crafts" on the other, Congress apparently means to accept the view that "boat, craft and watercraft" are usually applied to small vessels, while larger vessels are usually referred to by the terms "steamer, steamship or vessel" Test in determining whether a party is a common carrier of goods He must be engaged in the business of carrying goods for others as a public employment, and must hold himself out as ready to engage in the transportation of goods for person generally as a business and not as a casual occupation He must undertake to carry goods of the kind to which his business is confined. He must undertake to carry by the method by which his business is conducted and over his established roads. .. The transportation must be for hire. [First Philippine Industrial Corp. v. CA, G.R. 125948, Dec. 29, 1998] Provided it has space, for all who opt to avail themselves of its transportation service for a fee [National Steel Corp. v. CA, G.R. No. 112287, Dec. 12, 1997, quoting Mendoza v. PAL, 90 Phil. 836] Common Carrier: Basic Rules STILL A COMMON CARRIER: Even if hauling is only ancillary. Even if clientele is limited. Even if it has no fixed and publicly known route, maintains no terminals and issues not tickets. Even if means transportation is not through motor vehicle.

Ancillary Activity Immaterial Art. 1732 makes no distinction between one whose principal business activity is carrying of persons or goods or both, and one who does such carrying only as an ancillary, nor does it make distinctions between one who offers the service to the general public or a narrow segment of the general population. Therefore, a party who back-hauled goods for other merchants from Manila to Pangasinan, even when such activity was only periodical or occasional and was not its principal line of business would be subject to the responsibilities and obligations of a common carrier. [See De Guzman v. CA, G.R. L-47822, Dec. 22, 1988] Limited Clientele Not a Defense Facts: Petitioner entered into a contract with SMC for the transfer of paper and kraft board from the port area to SMCs warehouse. Held: She is still a common carrier although she does not indiscriminately hold her services out to the public but offers the same to select parties with whom she may contract in the conduct of her business. [Virgines Calvo v. UCPB General Insurance Co., G.R. 148496, Mar. 19, 2002] Facts: Respondent shipping company transported the 75,000bags of cement to Petitioner in its barge. The bags of cement perished after its barge sank while being towed by a tug boat. Held: Respondent is a common carrier because it was engaged in the business of carrying goods for others for a fee. The regularity of its activities in the area indicates more than just a casual activity on its part. Neither can the concept of a common carrier change merely because individual contracts are executed or entered into with the patrons of the carrier. [Phil. American General Insurance Co., et al. v. PKS ShippingCo., G.R. 149038, Apr. 9, 2003] No fixed route, No terminal, No Ticket issued also not a Defense Facts: Petitioner is involved in the business of carrying goods through its barges. It has no fixed and publicly known route, maintains no terminals, and issues no tickets. Held: Petitioner is still a common carrier because its principal business is that of lighterage and drayage and it offers its barges to the public for carrying or transporting by water for compensation. [Asia Lighterage and Shipping, Inc. v. CA, G.R. 147246, Aug. 19, 2003] Drayage service is usually provided by a national trucking/shipping company or an International shipment brokerage firm in addition to the transportation of the freight to and from the exhibit site. Drayage service provides for: -Completing inbound carrier's receiving documents;

-Unloading and delivery of the goods to your booth/stand space from the receiving dock; -Storing of empty cartons/crates and extra products at aon/near-site warehouse; -Pickup of the goods from your booth/stand space to the receiving dock and loading back into the carrier; or -Completing outbound carrier's shipping documents. Means used in transporting not material [First Philippine Industrial Corp. v. CA, G.R. 147246, Aug. 19, Issue: Are pipeline operators common carriers as to subject them to business taxes on common carriers? Held: Yes. The Code makes no distinction as to the means of transporting, as long as it is by land, water or air. It does not provide that the transportation of the passengers or goods should be by motor vehicle. In fact, in the US, oil pipe line operators are considered common carriers. Also under the Petroleum Act of the Philippines (RA 387). Effect when Common Carrier enters into a charter party If only by contract of affreightment, whether voyage or time charter, it remains a common carrier. If by bareboat or demise charter, a common carrier is transformed into a private carrier. Planters Products Inc. v. CA, G.R. 101503, Sept. 15, 1993 It is only when the charter includes both the vessel and its crew, as in a bareboat or demise that a common carrier becomes private, at least insofar as the particular voyage covering the charter-party is concerned. Indubitably, a ship owner in a time or voyage charter retains possession and control of the ship, although her holds may, for the moment, be the property of the charterer. Common Carrier v. Private Carrier (National Steel Corp. v. CA, supra) The true nature of a common carrier is the carriage of passengers or goods, provided it has space, for all who opt to avail themselves of its transportation service for a fee. As a general rule, private carriage is undertaken by special agreement and carrier does not hold himself out to carry goods for the general public. In private carriage, the rights and obligations of parties, including liabilities for damage to cargo, are determined primarily by stipulations in their contract of carriage or charter party (demise or bareboat. In such case, the burden of proof is on the other party to show that the private carrier was responsible for the loss of, or injury to the cargo. FGU Insurance v. G.P. Sarmiento Trucking, G.R. 141910, Aug. 6, 2002 Facts:

GPS, as the exclusive hauler of Conception Industries, undertook to deliver thirty (30) units of Condura refrigerators from latters plant in Alabang to Dagupan City. While the truck was traversing the north diversion road along McArthur highway in Barangay Anupol, Bamban, Tarlac, it collided with an unidentified truck, causing it to fall into a deep canal, resulting in damage to the cargoes. Petitioner FGU as subrogee to Concepcion Industries filed a complaint for damages and breach of contract of carriage gainst GPS and its driver. Issue No. 1: WHETHER RESPONDENT GPS MAY BE CONSIDERED AS A COMMON CARRIER. Held: GPS, being an exclusive contractor and hauler of Concepcion Industries, Inc., rendering or offering its services to no other individual or entity, cannot be considered a common carrier. The above conclusion nothwithstanding, GPS cannot escape from liability. In culpa contractual, upon which the action of petitioner rests as being the subrogee of Concepcion Industries, Inc., the mere proof of the existence of the contract and the failure of its compliance justify, prima facie, a corresponding right of relief. A breach upon the contract confers upon the injured party a valid cause for recovering that which may have been lost or suffered. The remedy serves to preserve the interests of the promisee that may include his: Expectation interest," which is his interest in having the benefit of his bargain by being put in as good a position as he would have been in had the contract been performed; or ..Reliance interest," which is his interest in being reimbursed for loss caused by reliance on the contract by being put in as good a position as he would have been in had the contract not been made; or Restitution interest," which is his interest in having restored to him any benefit that he has conferred on the other party .. The effect of every infraction is to create a new duty, that is, to make recompense to the one who has been injured by the failure of another to observe his contractual obligation unless he can show extenuating circumstances, like proof of his exercise of due diligence(normally that of the diligence of a good father of a family or, exceptionally by stipulation or by law such as in the case of common carriers, that of extraordinary diligence) or of the attendance of fortuitous event, to excuse him from his ensuing liability. . In this case, the delivery of the goods in its custody to the place of destination -gives rise to a presumption of lack of care and corresponding liability on the part of the contractual obligor the burden being on him to establish otherwise. GPS has failed to do so. Respondent driver, on the other hand, without concrete proof of his negligence or fault, may not himself be ordered to pay petitioner. The driver, not being a party to the contract of carriage between petitioners principal and defendant, may not be held liable under the agreement. A contract can only bind the parties who have entered into it or their successors who have assumed their personality or their juridical position.

Consonantly with the axiom res inter alios acta aliis neque nocet prodest, such contract can neither favor nor prejudice a third person. Petitioners civil action against the driver can only be based on culpa aquiliana, which, unlike culpa contractual, would require the claimant for damages to prove negligence or fault on the part of the defendant.

Issue No. 2: WHETHER THE DOCTRINE OF RES IPSA LOQUITURIS APPLICABLE IN THE INSTANT CASE. Held: Res ipsa loquitur, a doctrine being invoked by petitioner, holds a defendant liable where the thing which caused the injury complained of is shown to be under the latter?s management and the accident is such that, in the ordinary course of things, cannot be expected to happen if those who have its management or control use proper care. It affords reasonable evidence, in the absence of explanation by the defendant, that the accident arose from want of care It is not a rule of substantive law and, as such, it does not create an independent ground of liability. Instead, it is regarded as a mode of proof, or a mere procedural convenience since it furnishes a substitute for, and relieves the plaintiff of, the burden of producing specific proof of negligence. The maxim simply places on the defendant the burden of going forward with the proof. Resort to the doctrine, however, may be allowed only when (a) the event is of a kind which does not ordinarily occur in the absence of negligence; (b) other responsible causes, including the conduct of the plaintiff and third persons, are sufficiently eliminated by the evidence; and (c) the indicated negligence is within the scope of the defendant's duty to the plaintiff. Thus, it is not applicable when an unexplained accident may be attributable to one of several causes, for some of which the defendant could not be responsible. Res ipsa loquitur generally finds relevance whether or not a contractual relationship exists between the plaintiff and the defendant, for the inference of negligence arises from the circumstances and nature of the occurrence and not from the nature of the relation of the parties. Nevertheless, the requirement that responsible causes other than those due to defendants conduct must first be eliminated, for the doctrine to apply, should be understood as being confined only to cases of pure (noncontractual) tort since obviously the presumption of negligence in culpa contractual, as previously so pointed out, immediately attaches by a failure of the covenant or its tenor. In the case of the truck driver, whose liability in a civil action is predicated on culpa acquiliana, while he admittedly can be said to have been in control and management of the vehicle which figured in the accident, it is not equally shown, however, that the accident could have been exclusively due to his negligence, a matter that can allow, forthwith, res ipsa loquitur to work against him. Common Carrier v. Towage

In towage, one vessel is hire to bring another vessel to another place. Thus, a tugboat may be hired by a common carrier to bring the vessel to a port. In this case, the operator of the tugboat cannot be considered a common carrier. In maritime law, towage refers to a service rendered to a vessel by towing for the mere purpose of expediting her voyage without reference to any circumstances of danger. It usually confined to vessels that have received no injury or damage. Common Carrier v. Arrastre An Arrastre operator performs the following functions: Receive, handle, care for, and deliver all merchandise imported and exported, upon or passing over Government-owned wharves and piers in the port; Record or check all merchandise which may bedelivered to said port at shipside; In general, furnish light, and water services and other incidental services in order to undertake its arrastre service Hence, the functions of an arrastre operator has nothing to do with the trade and business of navigation, nor to the use or operation of vessels. An arrastre operator is like a depositary or warehouseman. Even if the arrastre service depends on, assists, or furthers maritime transportation, it may be deemed merely incidental and does not make its service maritime Common Carrier v. Stevedoring The function of stevedores involve the loading and unloading of coastwise vessels calling at the port. Governing Laws on Common Carrier COASTWISE SHIPPING: -New Civil Code (Arts. 1732-1766) -Code of Commerce CARRIAGE FROM FOREIGN PORTS TO PHIL PORTS: -New Civil Code (primary) -Code of Commerce (suppletory) -Carriage of Goods by Sea Act [COGSA] (suppletory) .. CARRIAGE FROM PHIL PORT TO FOREIGN PORTS: -The laws of the country to which the goods are to be transported. OVERLAND TRANSPORTATION: -Civil Code (primary) -Code of Commerce (suppletorily) -R.A. 4136 [The Land Transportation and Traffic Code] AIR TRANSPORTATION: -Civil Code (primary) -Code of Commerce (suppletorily) -For international carriage Warsaw Convention [Convention for the Unification of Certain Rules Relating to the International Carriage by Air]

Nature of Business of Common Carriers, KMU V. Garcia, GR 115381, Dec. 23, 1994 Common carriers are public utilities within the contemplation of the public service law. Public utilities are privately owned and operated businesses whose services are essential to the general public. They are enterprises which specially cater to the needs of the public and conduce to their comfort and convenience. When, one devotes his property to a use in which the public has an interest, he, in effect grants to the public an interest in that use, and must submit to the control by the public for the common good, to the extent of the interest he has thus created. Salient Provisions in R.A. 4136 on Registration of Vehicles Motor vehicle defined: Any vehicle propelled by any power other than muscular power using the public highways, but excepting road rollers, trolley cars, streetsweepers, sprinklers, lawn mowers, bulldozers, graders, fork-lifts, amphibian trucks, and cranes if not used on public highways, vehicles which run only on rails or tracks, and tractors, trailers and traction engines of all kinds used exclusively for agricultural purposes. Trailers having any number of wheels, when propelled or intended to be propelled by attachment to a motor vehicle, shall be classified as separate motor vehicle with no power rating. The distinction between "passenger truck" and "passenger automobile" shall be that of common usage: Provided, That a motor vehicle registered for more than nine passengers shall be classified as "truck": And Provided, further, That a "truck with seating compartments at the back not used for hire shall be registered under special "S" classifications. In case of dispute, the Commissioner of Land Transportation shall determine the classification to which any special type of motor vehicle belongs. Articulated vehicle -means any motor vehicle with a trailer having no front axle and so attached that part of the trailer rests upon motor vehicle and a substantial part of the weight of the trailer and of its load is borne by the motor vehicle. Such a trailer shall be called as "semitrailer." Professional driver -means every and any driver hired or paid for driving or operating a motor vehicle, whether for private use or for hire to the public. Any person driving his own motor vehicle for hire is a professional driver. Owner -The actual legal owner of a motor vehicle, in whose name such vehicle is duly registered with the Land Transportation Commission. .. The "owner" of a government-owned motor vehicle is the head of the office or the chief of the Bureau to which the said motor vehicle belongs. Parking or parked -A motor vehicle is "parked" or "parking" if it has been brought to a stop on the shoulder or proper edge of a highway, and remains inactive in that place or close thereto for an appreciable period of time. A motor vehicle which properly stops merely to discharge a passenger or to take in a waiting passenger, or to load or unload a small quantity of freight with reasonable dispatch shall not be considered as "parked", if the motor vehicle again moves away without delay.

Sec. 5(a) -No motor vehicle shall be used or operated on or upon any public highway of the Philippines unless the same is properly registered for the current year in accordance with the provisions of this Act. Sec. 5(e) Encumbrances of motor vehicles. Mortgages, attachments, and other encumbrances of motor vehicles, in order to be valid, must be recorded in the Land Transportation Commission and must be properly recorded on the face of all outstanding copies of the certificates of registration of the vehicle concerned. Section 16. Suspension of registration certificate. -If on inspection, as provided in paragraph (6) of Section four hereof, any motor vehicle is found to be unsightly, unsafe, overloaded, improperly marked or equipped, or otherwise unfit to be operated, or capable of causing excessive damage to the highways, or not conforming to minimum standards and specifications, the Commissioner may refuse to register the said motor vehicle, or if already registered, may require the number plates thereof to be surrendered to him, and upon seventy-two hours notice to the owner of the motor vehicle, suspend such registration until the defects of the vehicle are corrected and/or the minimum standards and specifications fully complied with. Section 21. Operation of motor vehicles by tourists. -Bona fide tourist and similar transients who are duly licensed to operate motor vehicles in their respective countries may be allowed to operate motor vehicles during but not after ninety days of their sojourn in the Philippines. After ninety days, any tourist or transient desiring to operate motor vehicles shall pay fees and obtain and carry a license as hereinafter provided. If any accident involving such tourist or transient occurs, which upon investigation by the Commissioner or his deputies indicates that the said tourist or transient is incompetent to operate motor vehicles, the Commissioner shall immediately inform the said tourist or transient in writing that he shall no longer be permitted to operate a motor vehicle. Speed Restrictions Section 35(a) Any person driving a motor vehicle on a highway shall drive the same at a careful and prudent speed, not greater nor less than is reasonable and proper, having due regard for the traffic, the width of the highway, and of any other condition then and there existing; and No person shall drive any motor vehicle upon a highway at such a speed as to endanger the life, limb and property of any person, nor at a speed greater than will permit him to bring the vehicle to a stop within the assured clear distance ahead.

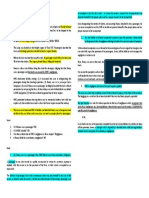

20 km. per hour 20 km. per hour 4. Through crowded streets, approaching intersections at "blind corners," passing school zones, passing other vehicles which are stationery, or for similar dangerous circumstance 30 km. per hour 30 km. per hour 3. On city and municipal streets, with light traffic, when not designated through streets 30 km. per hour 40 km. per hour 2. On "through streets" or boulevards, clear of traffic, with no " blind corners, when so designated. 50 km. per hour 80 km. per hour 1. On open country roads, with no "blinds corners" not closely bordered by habitations Motor trucks and buses Passengers Cars and Motorcycle MAXIMUM ALLOWABLE SPEEDS 20 km. per hour 20 km. per hour 4. Through crowded streets, approaching intersections at "blind corners," passing school zones, passing other vehicles which are stationery, or for similar dangerous circumstance 30 km. per hour 30 km. per hour 3. On city and municipal streets, with light traffic, when not designated through streets 30 km. per hour 40 km. per hour 2. On "through streets" or boulevards, clear of traffic, with no " blind corners, when so designated. 50 km. per hour 80 km. per hour 1. On open country roads, with no "blinds corners" not closely bordered by habitations Motor trucks and buses Passengers Cars and Motorcycle MAXIMUM ALLOWABLE SPEEDS

Exceptions to Rate Speed A physician or his driver when the former responds to emergency calls; The driver of a hospital ambulance on the way to and from the place of accident or other emergency; Any driver bringing a wounded or sick person for emergency treatment to a hospital, clinic, or any other similar place; The driver of a motor vehicle belonging to the Armed Forces while in use for official purposes in times of riot, insurrection or invasion; The driver of a vehicle, when he or his passengers are in pursuit of a criminal; A law-enforcement officer who is trying to overtake a violator of traffic laws; and The driver officially operating a motor vehicle of any fire department, provided that exemption shall not be construed to allow useless or unnecessary fast driving of drivers aforementioned. Section 36. Speed limits uniform throughout the Philippines. No provincial, city or municipal authority shall enact or enforce any ordinance or resolution specifying maximum allowable speeds other than those provided in this Act. Correct Driving Pass to the right when meeting persons or vehicle s coming toward him. Pass left when overtaking persons or vehicles going the same direction. Conduct to the right of the center of the intersection of the highway when turning left. Applicable every person operating a motor vehicle or ananimal-drawn vehicle. Exceptions: Different course of action is required in the interest of the safety and the security of life, person or property; or Because of unreasonable difficulty of operation in its compliance. Overtaking a vehicle [Sec. 39] Pass at a safe distance to the left; Not again drive to the right side of the highway until safety is clear of such overtaken vehicle. Exceptions: Passing at right allowed On highways with two or more lanes; or When to be overtaken vehicle is turning left.

Duty of Driver of Vehicle to be Overtaken [Sec. 40] To give way to the overtaking vehicle on suitable and audible signal being given by the driver of the overtaking vehicle; and Not to increase the speed of his vehicle until completely passed by the overtaking vehicle. Restrictions on overtaking and passing [Sec. 41] Do not drive to the left side of the center line of a highway in overtaking or passing another vehicle proceeding in the same direction, unless such left side is clearly visible, and is free of oncoming traffic for a sufficient distance ahead to permit such overtaking or passing to be made in safety. Do not overtake: when approaching the crest of a grade; upon a curve in the highway; driver's view along the highway is obstructed within a distance of five hundred feet ahead. Exception: When on a highway having two or more lanes for movement of traffic in one direction where the driver of a vehicle may overtake or pass another vehicle: Provided, Exception to exception: On a highway within a business or residential district, having two or more lanes for movement of traffic in one direction, overtaking or passing at right is allowed.

Do not overtake: Do not overtake: at any railway grade crossing; at any intersection of highways unless such intersectionor crossing is controlled by traffic signal, or unlesspermitted to do so by a watchman or a peace officer. Exception: On a highway having two or more lanes formovement of traffic in one direction where the driver of a vehicle may overtake or pass another vehicle on theright. Nothing in this section shall be construed to prohibit adriver overtaking or passing upon the right anothervehicle which is making or about to make a left turn.

Do not overtake, pass or attempt to pass: between any points indicated by the placing of official temporary warning or caution signs indicating that men are working on the highway; in any "no-passing or overtaking zone."

Right of way [Sec. 42] When two vehicles approach or enter an intersection at approximately the same time: Driver of the vehicle on the left to yield the right of way to the vehicle on the right; Driver of vehicle traveling at an unlawful speed forfeits right of way.

Driver of a vehicle approaching but not having enteredan intersection: To yield right of way to a vehicle within suchintersection or turning therein to the left across the line oftravel of such first-mentioned vehicle; Provided, driver of the vehicle turning left has given aplainly visible signal of intention to turn.

Driver of any vehicle upon a highway within a businessor residential district: To yield right of way to a pedestrian crossing such highway within a crosswalk; Exception: at intersections where the movement of traffic is being regulated by a peace officer or by traffic signal. Every pedestrian crossing a highway within a businessor residential district, at any point other than a crosswalkshall yield the right of way to vehicles upon thehighway.

When about to approach through highway or raildroad crossing: Full stop before traversing; Provided, That when it is apparent that no hazard exists, the vehicle may be slowed down to five miles per hour instead of bringing it to a full stop.

Exception to the right of way rule [Sec. 43] Yield right of way to all vehicles approaching whenentering a highway from a private road or drive; Yield to police or fire department vehicles andambulances when such vehicles are operated on officialbusiness and the drivers thereof sound audible signal oftheir approach;

Yield to all vehicles approaching from either directionwhen entering a "through highway" or a "stopintersection. Provided, That nothing in this subsection shall beconstrued as relieving the driver of any vehicle beingoperated on a "through highway" from the duty ofdriving with due regard for the safety of vehiclesentering such "through highway" nor as protectingthe said driver from the consequence of an arbitraryexercise off such right of way.

NO PARKING (a) Within an intersection (b) On a crosswalk (c) Within six meters of the intersection of curb lines. (d) Within four meters of the driveway entrance toand fire station. (e) Within four meters of fire hydrant (f) In front of a private driveway (g) On the roadway side of any vehicle stopped orparked at the curb or edge of the highway (h) At any place where official signs have been erected prohibiting parking.

Reckless driving [Sec. 48]

No person shall operate a motor vehicle on any highway recklessly or without reasonable caution considering the width, traffic, grades, crossing, curvatures, visibility and other conditions of the highway and the conditions of the atmosphere and weather, or so as to endanger the property or the safety or rights of any person or so as to cause excessive or unreasonable damage to the highway.

Right of way for police & other emergency vehicles [Sec. 49] Upon the approach of any police or fire departmentvehicle, or of an ambulance giving audible signal, The driver of every other vehicle shall immediatelydrive the same to a position as near as possible andparallel to the right-hand edge or curb of thehighway Clear of any intersection of highways, and Shall stop and remain in such position, unlessotherwise directed by a peace officer, until suchvehicle shall have passed.

Vehicle Tampering [Sec. 50] No unauthorized person shall sound the horn, handle the levers or set in motion or in any way tamper with a damage or deface any motor vehicle.

Prohibition on Vehicle Hitching [Sec. 51] No person shall hang on to, ride on, the outside or the rear end of any vehicle; and No person on a bicycle, roller skate or other similar device, shall hold fast to or hitch on to any moving vehicle; and No driver shall knowingly permit any person to hang on to or ride, the outside or rear end of his vehicle or allow any person on a bicycle, roller skate or other similar device to hold fast or hitch to his vehicle.

Prohibition on Sidewalk Driving or Parking [Sec. 52] No person shall drive or park a motor vehicle upon or along any sidewalk, path or alley not intended for vehicular traffic or parking.

Driving Under The Influence [Sec.53] No person shall drive a motor vehicle while under the influence of liquor or narcotic drug.

Obstruction of Traffic [Sec. 54] No person shall drive his motor vehicle in such a manner as to obstruct or impede the passage of any vehicle; Nor, while discharging or taking on passengers or loading or unloading freight, obstruct the free passage of other vehicles on the highway.

Duty of Driver In Case of Accident [Sec. 55] In the event that any accident should occur as a result of the operation of a motor vehicle upon a highway, the driver present, shall show his driver's license, give his true name and address and also the true name and address of the owner of the motor vehicle.

.. No driver of a motor vehicle concerned in a vehicular accident shall leave the scene of the accident without aiding the victim, except under any of the followingcircumstances: 1. If he is in imminent danger of being seriouslyharmed by any person or persons by reason of theaccident; 2. If he reports the accident to the nearest officer ofthe law; or 3. If he has to summon a physician or nurse to aidthe victim.

Traffic Violations For registering later than seven days after acquiringtitle to an unregistered motor vehicle or afterconversion of a registered motor vehicle requiringlarger registration fee than that for which it wasoriginally registered, or for renewal of a delinquentregistration. For failure to sign driver's license or to carry samewhile driving.

Driving a vehicle with a delinquent or invalid driver's license Driving a motor vehicle with delinquent, suspended or invalid registration, or without registration or without the proper license plate for the current year Driving a motor vehicle without first securing a driver's license

Driving a motor vehicle while under the influence of liquor or narcotic drug. Violation of Section thirty-two, thirty-four (a), (b) and (b1), thirty-five and forty-six Violations of Sections forty-nine, fifty and fifty-two.

For making, using or attempting to make or use adriver's license, badge, certificate or registration, numberplate, tag or permit in imitation or similitude of thoseissued under this Act, or intended to be used as or for alegal license, badge, certificate, plate, tag or permit orwith intent to sell or otherwise dispose of the same toanother, or false or fraudulently represent as valid andin force any driver's license, badge, certificate, plate, tagor permit issued under this Act which is delinquent orwhich has been suspended or revoked

For using private passenger automobiles, private trucks, private motorcycles, and motor wheel attachments for hire, in violation of Section seven, subsections (a), (b), and (c), of this Act For permitting, allowing, consenting to, or tolerating the use of a privately-owned motor vehicle for hire in violation of Section seven, subsections (a), (b), and (c), of this Act,

For violation of any provisions of this Act or regulationspromulgated pursuant hereto, not hereinbeforespecifically punished In the event an offender cannot pay any fine imposedpursuant to the provisions of this Act, he shall be madeto undergo subsidiary imprisonment as provided for inthe Revised Penal Code.

If, as the result of negligence or reckless or unreasonable fast driving, any accident occurs resulting in death or injury of any person, the motor vehicle operator at fault shall, upon conviction, be punished under the provisions of the Revised Penal Code.

Presumption of Negligence Art. 2185, Civil Code It is presumed that a person driving a motor vehicle is negligent if at the time of the mishap, he was violating any traffic regulation, unless the contrary.

Registered Owner Rule The person who is the registered owner of a vehicle isliable for any damage caused by the negligentoperation of the vehicle although the same wasalready sold or conveyed to another person at thetime of the accident. This is subject to the right of recourse by theregistered owner against the transferee or buyer. The registered owner rule is applicable whenever thepersons involved are engaged in what is known asthe kabit system.

CLASSIFICATIONS OF MOTOR REGISTRABLE VEHICLES [Sec. 7] CLASSIFICATIONS OF MOTOR REGISTRABLE VEHICLES [Sec. 7] a) Private passengerautomobiles; b) Private trucks; c) Private motorcycles, scooters, or motor wheel attachments d) Public utilityautomobiles; e) Public utility trucks; f) Taxis and auto-calesas g) Garage automobiles h) Garage trucks i) Hire trucks; j) Trucks owned bycontractors and customs brokers and customs agents; k) Undertakes; l) Dealers; m) Government automobiles n) Government trucks; o) Government motorcycles; p) Motor vehicles oftourists [for 90 days]; q) Special

.. Vehicles registered under classification under (a), (b) & (c) cannot be used for hire under any circumstances andcannot be used to solicit, accept, or be used to transportpassengers or freight for pay. Laborers necessary to handle freight in private trucksmay ride on it (but not to exceed 10 laborers) Dealers vehicle can be operated only for the purpose of transporting the vehicle itself from the pier or factory to the warehouse or sales room or for delivery to a prospective purchaser or for test or demonstration

CONCLUSIVE PRESUMPTION OF A VEHICLE IS FOR HIRE A vehicle habitually used to carry freight not belonging to the registered owner thereof, or passengers not related by consanguinity or affinity within the fourth civil degree to such owner, shall be conclusively presumed to be "for hire."

KABIT SYSTEM It is an arrangement whereby a person who has beengranted a certificate of public convenience allowsother persons who own motor vehicles to operatethem under his license, sometime for a fee or percentage of earning. Such arrangement is void for being contrary to publicpolicy [Abelardo Lim, et al. v. CA, GR 125817, Jan. 16,2002]

PARTIES IN KABIT SYSTEM COVERED BY IN PARI DELICTO RULE Ex pact illicito non oritur action No action arises out of an illicit bargain. Having entered into an illegal contract, parties to the kabit system cannot seek relief from the courts, and each must bear the consequences of his acts.

Teja Marketing v. IAC, GR 65510, Mar. 9, 1987 Facts: Petitioner was constrained to file an action for damages because private respondent allegedly failedto pay the balance of the purchase price of itsmotorcycle sold. The motorcycle which was used forsidecar remained under the name of petitioner andoperated under its franchise under an arrangementcalled kabit system. Held: Dismissal of case sustained. Both parties are in pari delicto. The court will not aid either party to enforce an illegal contract.

Chapter 2 OBLIGATIONS OF THE PARTIES

OBLIGATION OF CARRIER: Duty to Accept; Duty to Deliver Goods On Time; Duty to Deliver Goods at the Place and to the person named in the BL; and Duty to Exercise Due Diligence

OBLIGATION OF SHIPPER OR PASSENGER Duty to exercise due diligence. Duty to pay the amount of freight or passage on time.

1. Carriers Duty to Accept A common carrier granted CPC is duty bound to accept passengers or cargo without any discrimination. Exceptions: Dangerous objects or substances including dynamites and other explosives; Unfit for transportation; Acceptance would result in overloading;

Contrabands or illegal goods; Goods are injurious to health; Good will likely be exposed to untoward danger like flood, capture by enemies and the like; Livestock with disease or exposed to disease; Strike; and Failure to tender goods on time

Rule on Hazardous and Dangerous Substances A carrier may be granted authority to carry goods that are by nature dangerous and hazardous. A carrier specially designed to carry dangerous chemicals and goods may be granted CPC for such purpose. All other carriers may validly refuse to accept such cargoes.

MARINA Memorandum Circular No. 105, Apr. 6, 1995 Documentary Requirements for Special Permit to Carry Dangerous/Hazardous Cargoes and Goods in Packaged Form: Letter of Intent PPA Clearance on packaging, marking and labeling of cargoes or goods in packaged forms Cargo Stowage Plan

Classification of Dangerous or Hazardous Goods Under MC 105 Class 1 Explosives Class 2 Gases: Compressed, liquefied or dissolvedunder pressure Class 3 Inflammable Liquids Class 4 Inflammable Solids or Substances: a) Inflammable Solid; b) Inflammable Solids, or Substancesliable to spontaneous combustion; and c) InflammableSolids, or Substances which in contact with waters emitinflammable gases;

Class 5 a) Oxidizing Substances; b) OrganicPeroxide Class 6 -a) Poisonous (toxic) substances; b) Infectious Substances Class 7 Radioactive Substances Class 8 Corrosives Class 9 Miscellaneous Dangerous Substances

MARINA Memorandum Circular No. 147 Rules on carriage of vehicles, animals, forest products, fish and aquatic products, minerals and mineral products & toxic and hazardous materials on board vessels: Master to accept only if these are covered by necessary clearance from appropriate agencies; Non-compliance will subject the shipowner and master administrative penalties without prejudice to criminal or civil suits

2. Carriers Duty to Deliver The Goods General Rule: Carrier is not an insurer against delay in transportation of goods. Exception: When there is agreement as to the time of delivery

When delay is deemed reasonable Ordinary Goods 2 months [Maersk Line v. CA, May 17, 1993] Perishable Goods 2 to 3 days [Dissenting: Tan Chiong Sian v. Inchausti, GR 6092, Mar. 8, 1912]

Rules on Delay on Overland Transportation (Code of Commerce) Art. 358, Code of Commerce: If there is no period fixed for the delivery of the goods the carrier shall be bound to forward them in the first shipment of the same or similar goods which he may make to the point of delivery; and should he not do so, the damages caused by the delay should be for his account.

Delay When Period Is Fixed Art. 370. If a period has been fixed for the delivery of the goods, it must be made within such time, and, for failure to do so, the carrier shall pay the indemnity stipulated in the bill of lading, neither the shipper nor the consignee being entitled to anything else. If no indemnity has been stipulated and the delay exceeds the time fixed in the BL, the carrier shall be liable for the damages which the delay may have caused.

Procedure in Abandonment by Consignee In Case of Delay (Type 2) Art. 371. In case of delay through the fault of thecarrier referred to in the preceding articles, theconsignee may leave the goods transported in thehands of the former, advising him thereof in writingbefore their arrival at the point of destination. When this abandonment takes place, the carrier shallpay the full value of the goods as if they had been lostor mislaid.

If the abandonment is not made, the indemnification for the losses and damages by reason of the delaycannot exceed the current price which the goodstransported would have had on the day and at theplace in which they should have been delivered; thissame rule is to be observed in all other cases in which this indemnity may be due.

FIVE TYPES OF ABANDONMENT UNDER MERCANTILE LAW WHEN DAMAGE IS SO GREAT [Art. 365, Code ofCommerce] WHEN GOODS ARRIVE BEYOND THE DATE AGREED ON [Art. 371, Code of Commerce] ABANDONMENT BY SHIPOWNER WHEN LIABILITY EXCEEDS VALUE OF VESSEL [Art. 578, Code of Commerce] DAMAGE TO GOODS IN LIQUID FORM [Sec. 687, Code of Commerce] CONSTRUCTIVE LOSS UNDER THE INSURANCE CODE [Sec. 138, Insurance Code of the Phil.]

1st Type: WHEN DAMAGE IS SO GREAT Where the shipper ships goods and goods arrive indamaged condition and damage is so great thatshipper may not use goods for the purpose for whichthey have been shipped, the shipper may exerciseright of abandonment. NOTICE TO THE CARRIER IS SUFFICIENT consent of carrier is not necessary and once perfected, the ownership over damaged goods passes to thecarrier and carrier must pay the shipper market valueof goods at point of destination.

2nd Type: WHEN GOODS ARRIVE BEYOND DATE AGREE ON Under this set-up, shipper and carrier agreed in advance that cargo must arrive on a certain date. The date has passed but the cargo has not yet arriveddue to carriers fault. Shipper/consignee may exercise the right of abandonment by NOTIFYING the carrier. Once carrier has been notified, ownership over thegoods undelivered passes to carrier. But carrier must pay shipper market value of thegoods at the point of destination.

3rd Type: ABANDONMENT BY SHIPOWNER WHEN LIABILITY EXCEEDS VALUE OF VESSEL Reflects the hypothecary nature of maritime transactions. Instances when vessel carries goods and goods are damaged. Liability of the carrier over the damage goods exceedsthe value of the vessel. Shipowner of ship agent may exercise right of abandonment by simply NOTIFYING TO THE SHIPPER. Liability of the shipowner is now limited to the value ofthe vessel.

4th Type: DAMAGE TO GOODS IN LIQUID FORM Charterers and shippers may abandon the merchandise damaged if cargo should consist of liquids; The contents have leaked out; What remains in the container is but of its content; The cause was on account of inherent defect or fortuitous event.

5th Type: CONSTRUCTIVE LOSS UNDER THE INSURANCE CODE

Shipowners right of abandonment for constructive loss; Takes place when vessel suffers damage in excess of of its insured value; Notice to Insurer from the insured is sufficient; Thereafter, ownership over the damaged vessel passes to the insurer; and Insurer must pay insured as if it were an ACTUAL LOSS.

Characteristics of Abandonment It is unilateral right; It is perfected by mere notice; Once perfected, ownership over damaged goods passes to carrier; and Carrier must pay the shipper market value of goods at the point of destination

Bar, Mercantile Law [1979] Problem: A, in Manila, shipped on board a vessel of B, chairs tobe used in the moviehouse of consignee C in Cebu. No date for delivery or indemnity for delay wasstipulated. The chairs, however, were not claimedpromptly by C and were shipped by mistake back toManila, where it was discovered and re-shipped toCebu. By the time the chairs arrived, the date ofinauguration of the moviehouse passed by and it hadto be postponed. C brings an action for damagesagainst B claiming loss of profits during theChristmas season when he expected the moviehouseto be opened. Decide the case with reason

Suggested Answer: C may sue B for the loss of his profits provided that ample proof thereof are presented in court. The carrier is obligated to transport the goods without delay. The carrier is liable if he is guilty of delay in the shipment of cargo, causing damages to the consignee.

Mora in Civil Law distinguished from Mora in Mercantile Law Under Art. 1169, Civil Code requires demand by the creditor in order that delay may exist. Exceptions: Obligation or law expressly so provides; Time is of the essence; and Demand would be useless.

BUT under the Code of Commerce, demand, as a generalrule, is not necessary in commercial contracts in order forthe obligor to incur delay [Arts. 61, 62 & 63, Code ofCommerce]. Exceptions: a) When fixed by contract, b) when recognized or allowed by law. In commercial contracts, time is always of the essence.

Code of Commerce Provisions on Mora [Arts. 61, 62,& 63] Art. 61. Day of grace, courtesy or others which underany name whatsoever defer the fulfillment ofcommercial obligations, shall not be recognized, except those which the parties may have previouslyfixed in contract or which are based on a definite provision of law. Art. 62. Obligations which do not have a periodpreviously fixed by the parties or by the provisions ofthis Code, shall be demandable ten days after havingbeen contracted if they give rise only to an ordinaryaction, and on the next day if they involve immediateexecution.

..Art. 63. The effect of default in the performance ofcommercial obligation shall commence: 1. In contracts with a day for performance fixed bythe will of the parties or by the law, on the day followingtheir maturity; 2. In those which do not have such day fixed, fromthe day on which the creditor makes judicial demand onthe debtor or notifies him of protest of loss and damagesmade against him before a judge, notary or other publicofficial authorized to admit the same.

SUMMARY: When Debtor incurs Delay in Commercial Contracts

If period of performance is fixed, debtor incurs delaythe day following the day fixed, without need ofdemand; If no period fixed, ten (10) days from execution ofcontract and on 11th day, debtor incurs delay without need of demand; Potestative period (e.g. when the debtor desires) debtor in delay from date of demand. Note: distinguish from a potestative condition, e.g. ifthe debtor desires. Under the Civil Code and Code of Commerce, such condition is void.

KINDS OF DELAY UNDER CIVIL CODE Mora solvendi Delay of an obligor to deliver or toperform an obligation: a. Mora solvendi ex re delay when the obligation is to give or to deliver; b. Mora solvendi ex persona delay when the obligationis to do or to perform a personal service. Mora accipiendi Delay of an obligee in accepting thedelivery of the thing due; Compensatio morae Delay in reciprocal obligations(Art. 1169, last par.). Neither party is in default unlessthe other is ready to comply with his obligation.

UNDER CIVIL CODE: DEMAND NECESSARY FOR DELAY In Compania General de Tabacos vs. Araza, 7 Phil. 455, held: The contract does not provide for the payment of any interest. There is no provision in it declaring expressly that the failure to pay when due should put the debtor in default. There was therefore no default which would make him liable for interest until a demand was made. There was no evidence of any demand prior to the presentation of the complaint. The plaintiff is therefore entitled to interest only from the commencement of the action.

DEEMED MERCHANCE UNDER THE CODE OF COMMERCE Those who, having legal capacity to engage in commerce, habitually devote themselves thereto [Art. 1] Legal presumption of habituality: From the moment a person who intends to engage in commerce announces through circulars, newspapers, handbills, posters exhibited to the public, or in any manner whatsoever, an establishment which has for its object some commercial operation [Art. 3]

COMMERCIAL CONTRACTS GOVERNED BY CODE OF COMMERCE Art. 50. Commercial contracts, in everything relativeto their requisites, modifications, exceptions, interpretations, and extinction and to the capacity oftheir contracting parties, shall be governed in allmatters not expressly provided for in this Code or inspecial laws, by the general rules of civil law. HIERARCHICAL APPLICABILITY OF LAWS TO COMMERCIAL TRANSACTIONS: 1. Code of Commerce 2. Commercial customs (in the absence of #1); and 3. Civil Code (in the absence of 1 & 2)

PERFECTION OF COMMERCIAL CONTRACTS BY CORRESPONDENCE Art. 54. Contracts entered into by correspondence shall be perfected from the moment an ANSWER IS MADE ACCEPTING THE OFFER OR THE CONDITIONS by which the latter may be modified. Above is in contrast to Art. 1319, NCC where negotiated contracts by correspondence are perfected only FROM THE TIME THE OFFEROR HAS ACTUAL KNOWLEDGE OF ACCEPTANCE

PERFECTION OF COMMERCIAL CONTRACTS BY AGENT OR BROKER Art. 55. Contracts in which an agent or broker intervenes shall be perfected WHEN THE CONTRACTING PARTIES SHALL HAVE ACCEPTED HIS OFFER. Compare Art. 1989, NCC: If the agent contracts in thename of the principal, exceeding the scope of his authority, and the principal does not ratify the contract, it shall bevoid if the party with whom the agent contracted is awareof the limits of the powers granted by the principal. In thiscase, however, the agent is liable if he undertook to securethe principals ratification.

CONSEQUENCE OF DELAY Art. 1740, NCC: If the common carrier negligently incurs in delay in transporting the goods, a natural disaster shall not free such carrier from responsibility. Art. 1747: If the common carrier, without just cause, delays the transportation of the goods or changes the stipulated or usual route, the contract limiting the common carriers liability cannot be availed of in case of the loss, destruction or deterioration of the goods

RIGHT OF PASSENGER IN CASE OF DELAY Code of Commerce: Art. 698 In case a voyage already begun has been interrupted; Passengers to pay the fare in proportion to the distance covered; No right to recover for losses and damages if interruption is due to fortuitous event or force majeure;

Except when interruption was caused by the Captainexclusively. If interruption is due to disability of the vessel andpassenger agrees to await the repair; He is not required to pay any increased price of passage; BUT HIS LIVING EXPENSES DURING THE STAY FOR HIS OWN ACCOUNT. (But see MARINA MC112)

MARINA MEMORANDUM CIRCULAR NO. 112 In case the vessel cannot continue or complete her voyage FOR ANY CAUSE; Carrier is under obligation to transport the passenger to his/her destination AT THE EXPENSE OF THE CARRIER including FREE MEALS and LODGING before said passenger is transported to his destination.

A passenger may opt to have his ticket refunded in full if the cause of the unfinished voyage is due to the negligence of the carrier; or To an amount that will suffice to defray transportation cost at the shortest possible route towards his destination if the cause is fortuitous event.

If arrival is delayed, carrier shall provide for meals, freeof charge, during mealtime. If departure is delayed due to carriers negligence, carrier is also under the obligation to provide meals, freeof charge, during meal time to TICKETEDPASSENGERS for the particular voyage. If departure is delayed due to fortuitous event, thecarrier is under no obligation to serve free meals to the passengers.

3. CARRIERS DUY TO DELIVER GOODS AT THE PLACE DESIGNATED AND TO PERSON NAME IN BL Art. 360 (Code of Commerce): The shipper may change the consignment of goods, without necessarily changing the place of delivery; But must, at the time of ordering the change of consigneein the BL signed by the carrier; Return the BL to the carrier in lieu of another BL containing the novated contract. Expenses of the change of consignee at the expense ofthe shipper.

Bar, Mercantile Law [1975] Bar Question: If a shipper, without changing the place of delivery changes the consignment of consignee of the goods (after said goods had been delivered to the carrier), under what condition will the carrier be required to comply with the new order of the shipper?

Suggested Answer: Art. 360 of the Code of Commerce provides that if the shipper should change the consignee of the goods without changing their destination, the carrier shall comply with the new order provided the shipper RETURNS TO THE CARRIER the bill of lading and a new one is issued shoving the novation of the contract. However, all expenses for the change must be paid by the shipper.

4. CARRIER DUTY TO EXERCISE EXTRAORDINARY DILIGENCE Art. 1733 (NCC). Common carriers, from the nature oftheir business and for reasons of public policy, arebound to observe extraordinary diligence in the vigilanceover the goods and for the safety of the passengerstransported by them, according to all the circumstancesof each case.

Such extraordinary diligence in the vigilance over the goods is further expressed in Arts. 1734, 1735, and 1745, Nos. 5, 6, and 7, while the extraordinary diligence for the safety of the passengers is further set forth in Arts. 1755 and 1756.

Art. 1755. A common carrier is bound to carry the passengers safely as far as human care and foresight can provide, using the utmost diligence of very cautious persons, with a due regard for all the circumstances.

The foregoing provisions in the Civil Code modify Arts. 363, 364 & 365 of the Code of Commerce: Art. 363 on the requirement of the carrier to deliver thegoods shipped in the same condition where they werefound at the time they were received; and Art. 364 on when damage is merely diminution in thevalue of the goods, carriers liability shall be reduced tothe payment of the amount constituting the difference invalue determined by experts.

Art. 365 on instance when goods are rendered useless for sale and consumption for the purposes they are destined, consignee may not receive them and may demand only their value at the current price of the day.

PRESUMPTION OF NEGLIGENCE In case of loss of effects or cargo; or In case of death or injury of passenger; Common carrier is presumed to be at fault; Unless, it can prove that it had observed extraordinary diligence in the vigilance thereof.

BATANGAS TRANSPORT CO. v. CAGUIMBAL, ET AL., G.R. L-22985, Jan. 24, 1968 In an action based on a contract of carriage, the court need not make an express finding of fault or negligence on the part of the carrier in order to hold it responsible to pay the damages sought; It is sufficient that plaintiff shows: a) there exist a contract between the passenger or the shipper and the common carrier; and b) the loss, deterioration, injury or death took place during the subsistence of the contract.

MRASOL v. THE ROBERT DOLLAR COMPANY, G.R. L-29721, Mar. 27, 1929 Facts: Mirasol is consignee of two cases of Encyclopedia Britannica books that he ordered from New York, shipped in good order and condition on board MS President Garfield, principal defendant company. The books arrived in bad order and condition. There was total loss of one case and partial loss on the other, all in all amounting to P2,080.

Held: Defendant having received the two boxes in goodcondition, its legal duty was to deliver them to theplaintiff in the same condition in which it received them. As the boxes were damaged while in transit, the burdenof proof then shifted, and it devolved upon thedefendant to both allege and prove that the damage wascaused by reason of some fact which exempted it fromliability.

As to how the boxes were damaged, was a matter peculiarly and exclusively within the knowledge of the defendant. To require plaintiff to prove as to when and how the damage was caused would force him to call and rely upon the employees of the defendants ship. That is not the law.

The evidence for the defendant shows that the damagewas largely caused by sea water, from which itcontends that it is exempt. Damage by sea water, standing alone and within itself, is not evidence that they were damaged by force majeureor for a cause beyond defendants control. The words perils of the sea apply to all kinds of marine casualties, such as shipwreck, foundering, stranding, etc. Where the peril is the proximate cause of the loss, theshipowner is excused. But something fortuitous and outof the ordinary must be involved in both words peril oraccident

DURATION OF DUTY TO EXERCISE EXTRAORDINARY DILIGENCE [Carriage of Goods] Art. 1736, NCC: The extraordinary responsibility of the common carrier lasts from the time the goods are unconditionally placed in the possession of, and received by the carrier for transportation until the same are delivered, actually or constructively, by the carrier to the consignee, or the person who has a right to receive them, without prejudice to the provisions of Art. 1738.

Art. 1737 (NCC): Art. 1737 (NCC): The common carriers duty to observe extraordinarydiligence over the goods remains in full force and effecteven when they are temporarily unloaded or stored intransit, unless the shipper or owner has made use of theright of stoppage in transitu. Note: Right to stoppage in transitu is the right of theunpaid seller who has parted with the possession of thegoods, when the buyer is or becomes insolvent, to stopthem and resume possession while they are in transit. The unpaid seller will become entitled to the same rigthsto the goods, as if he had never parted with possession. [Art. 1530, NCC]

Art. 1738 (NCC): The extraordinary liability of the common carrier continues to be operative even during the time the goods are stored in a warehouse of the carrier at the place of destination, until the consignee has been advised of the arrival of the goods and has had reasonable opportunity thereafter to remove them or otherwise dispose of them.

ART. 1736 CONSTRUED [Macam v. CA, G.R. 125524, Aug. 25, 199] Facts: Ben-Mac Enterprises shipped on board MV NenJiang, represented by local agent Wallem Shipping, 3,500 boxes of watermelons valued at $5,950 and 1,611 boxed of fresh mangoes valued at $14,273 withPakistan Bank (Hongkong) as consignee and GreatProspect Co., Hongkong as Notify Party. In the BL, it was stipulated that One of the Bills ofLading must be surrendered duly endorsed inexchange for the goods or delivery order.

As per letter of credit requirement, copies of the BL and commercial invoices were submitted by Ben-Mac to SolidBank. The latter then paid Ben-Mac the total value of the shipment. Upon arrival in Hongkong, the shipment was delivereddirectly to GPC, not to Pakistan Bank and without therequired BL having been surrendered.

GPC failed to pay Pakistan Bank. Pakistan Bank refused to pay Ben-Mac through Solidbank. Since SolidBank already pre-paid Ben-Mac the value of the shipment, it demanded payment from Wallem but was refused. Ben-Mac was forced to refund SolidBank.

Held: Held: We emphasize that the extraordinary responsibility ofthe common carriers lasts until actual or constructive delivery of the cargoes to the consignee or TO THEPERSON WHO HAS A RIGHT TO RECEIVE THEM. Pakistan Bank was indicated in the BL as consigneewhereas GPC was the notify party. However, in theexport invoices GPC was clearly named asbuyer/importer. Ben-Mac also referred to GPC as suchin his demand letter to Wallem. This premise draws us to conclude that the delivery toGPC as buyer/importer which, conformably with Art. 1736 had, other than the consignee, the right to receivethem was proper.

DURATION OF DUTRY TO EXERCISE DILIGENCE [Carriage of Passengers] For Trains: Starts from the moment the person whopurchases the ticket (or token or card) from the carrierpresents himself at the proper place and in a propermanner to be transported with bona fide intent to ridethe coach. Same for Ships & Aircrafts. For jeepneys/buses: Starts from the time the person stepson the platform.

WHEN CONTRACT OF CARRIAGE ENDS The relation of carrier does not cease at the moment the passenger alights from the carriers vehicle but continues until the passenger has had a reasonable time or a reasonable opportunity to leave the carriers premises.

La Mallorca v. CA, G.R. L-20761, July 27, 1966 Facts: Plaintiffs, as husband and wife boarded PambuscoBus No. 352 together with their (3) minor daughtersfrom San Fernando, Pampanga to Anao, Mexico, Pampanga. All alighted at the designated place of unloading butMariano, the father had to return to the bus to get oneof his bayong left under his seat. Unknown to him, her daughter Raquel followed him. She was ran over by the bus when it started to runagain.

Held: There can be no controversy that as far as the father isconcerned, when he returned to the bus for his bayongwhich was not unloaded, the relation of passenger andcarrier does not necessarily cease where the latter, afteralighting from the car, aids the carriers conductor inremoving his baggage.

The issue to be determined here is whether as to the child, who was already led by the father to a place about5 meters away from the bus, the liability of the carrier forher safety under the contract of carriage also persisted. In the present case, the father returned to the bus to getone of his baggages which was not unloaded when theyalighted from the bus. Raquel, the child that she was, must have followed thefather.

However, although the father was still on the runningboard of the bus awaiting for the conductor to hand himthe bag or bayong, the bust started to run, so the eventhe father had to ump down from the moving vehicle. It was at this instance that the child, who must be near the bus, was run over and killed. In the circumstances, it cannot be claimed that the carriers agent had exercisedthe utmost diligence required under Art. 1755. The presence of said passengers near the bus was notunreasonable and they are, therefore, to be consideredstill as passengers of the carrier, entitled to the protectionunder their contract.

ABOITIZ SHIPPING v. CA, G.R. 84458, Nov. 6, 1989 Facts: Anacleto was a passenger of MV Antonia from SanJose, Mindoro to Manila. Upon reaching Pier 4, NorthHarbor, he disembarked from the ship by jumpingfrom the 3rd deck which is at level with the pier. After 1 hour when all the passengers have alreadydisembarked and the crane started unloading thecargoes, Anacleto went back to the vessel afterrealizing that he left some of his cargoes there. It was while he was pointing to the crew the placewhere his cargoes were loaded that the crane hit him. He later died. His heir sued Aboitiz for breach of contract of carriage.

Held: Held: In consonance with common shipping procedure as tothe minimum time of 1 hr. allowed for the passengers todisembark, it may be presumed that the victim had justgotten off the vessel when he went to retrieve hisbaggage. Yet, even if he had already disembarked an hour earlier, his presence in petitioners premises was not withoutcause. The victim had to claim his baggage which waspossible only one (1) hour after the vessel arrived since itwas admittedly standard procedure in the case ofpetitioners vessels that the unloading operations shallstart only after that time. Consequently, the victim Anacleto is still deemed passenger at the time of his tragic death.

1. Flood, storm, earthquake, lightning, or other naturaldisaster or calamity; DEFENSES OF COMMON CARRIERS [Art. 1734, NCC] 2. Act of public enemy in war, whether internationalor civil; 3. Act or omission of the shipper or owner of thegoods; 4. The character of the goods or defects in the packingor in the containers; and 5. Order or act of competent public authority. Note: The enumeration is exclusive; no other defensemay be raised by the CC.

DEFENSE NO. 1: FORTUITOUS EVENT Requisites: Independent of human will; Impossible to foresee or if it can be foreseen, impossible to avoid; Must be such as to render it impossible for the obligorto fulfill the obligation in a normal manner; and Obligor must be free from any participation in or theaggravation of the injury [Lasam v. Smith, No. 19495, Feb. 2, 1924]

For fortuitous event to be a valid defense: It must be the PROXIMATE AND ONLY CAUSE OF THE LOSS; Carrier must be free from any participation in causingthe damage or injury; It must exercise due diligence to prevent or minimize theloss BEFORE, DURING AND AFTER the fortuitous event. [Art. 1739, NCC]

TAN CHIONG SIAN v. INCHAUSTI, G.R. No. 6092, March 8, 1921 Justice Moreland speaking: An act of God cannot be urged for the protection of aperson who has been guilty of gross negligence in nottrying to avert its results. One who has accepted responsibility for pay can notweakly fold his hands and say that he was preventedfrom meeting that responsibility by an act of God, whenthe exercise of the ordinary care and prudence wouldhave averted the results flowing from that act.

One who has placed the property of another, intrusted tohis care, in an unseaworthy craft, upon dangerouswaters, cannot absolve himself by crying, an act of God, when every effect which a typhoon produced upon thatproperty could have been avoided by the exercise ofcommon care and prudence. When the negligence of the carrier concurs with an act ofGod producing a loss, the carrier is not expempted fromliability by showing that the immediate cause of thedamage was the act of God, or, as it has been expressed, when the loss is caused by the act of God, if thenegligence of the carrier mingles with it as an active andcooperative cause, he is still liable.

FIRE NOT A NATURAL DISASTER OR CALAMITY [Cokaliong v. UCPB Gen. Insurance, G.R. 146018, June 25, 2003] Facts: M/V Tandag sank after a crack from her auxiliary engines fuel tank caused the spurt of fuel towards the heating exhaust manifold ignited a fire in the engine room

Held: Fire is not considered a natural disaster or calamity. This must be so as it arises almost invariably from some act of man or by human means. It does not fall within the category of an act of God unless caused by lighting or by other natural disaster or calamity.

HIJACKING NOT AN EXEMPTING CAUSE A Common Carrier can be held liable for failing to prevent a hijacking by frisking passengers and inspecting their baggages, especially when it had received prior notice of such threat. (Fortune Express v. CA, 305 SCRA 14)

BATANGAS TRANS. v. CAGUIMBAL, 22 SCRA 171 (1967) Problem: A BLTB Bus going north stopped on thehighway because a passenger wanted to alight. Another bus was going south fast and recklessly, trying to pass a carretela. In trying to overtake thecarretela, the driver of the approaching bus made amiscalculation and hit the bus of BLTB. The passenger who was then alighting was thrown outand killed. The heirs of the victim sought recovery. BLTB raised the defense of fortuitous event.

Answer: BLTB is still liable. In civil law, where a fortuitous event concurs with negligence, liability is not extinguished. The BLTB bus was then in a stop position but since it did not stop on the shoulder of the road at the time the passenger was alighting, the same can be considered negligence that concurred with fortuitous event and did not operate to extinguish the liability.

Facts: FIRECRACKERS EXPLODING FROM PASSENGER BAGGAGE: CARRIER EXCUSED (Nocum v. LTD, 30 SCRA 69) One of the bus passengers had firecrackers inside hisbag. They exploded after another passenger smokedcigarettes causing injuries to another passenger. Theinjure passenger sought to recover from the carrier. Held: Carrier not liable. The carrier cannot be expected toexamine and search each and every piece of baggageof passengers, otherwise the bus may not all togetherbe able to leave. This is only true so long as the cause of the accidentwas not apparent and the carrier or its employees arenot guilty of negligence.

RULE ON MECHANICAL DEFECTS Facts: [Necesito v. Paras, 104 Phil. 75] A Phil. Rabbit Bus was traveling fast. During the tripthe driver sensed that the wheels did not respond tothe movement of the steering wheel. The bus hit a rut (pothole) and it turned turtle, killing a passenger. The mechanic of the bus company discovered that theworn-out gear of the steering wheel had a crack, which could not be seen by the naked eye from theoutside. The bus company proved that the defect wasattributable to General Motors, manufacturer of thebus and that the defect could not have been discovered by expert mechanics.

Held: As a rule, a passenger is entitled to recover damagesfrom a carrier for injury resulting from a defect in anappliance purchased from a manufacturer PROVIDEDIT APPEARS THAT THE DEFECT WOULD HAVE BEEN DISCOVERED BY THE CARRIER IF IT HAD EXERCISED THE DEGREE OF CARE WITH REGARD TO INSPECTION AND APPLICATION OF THE NECESSARY TESTS. When the defect is LATENT, i.e. cannot be discovered bythe application of any known tests, then it qualifies as afortuitous event to exempt the common carrier fromliability.

YOBIDO v. CA, G.R. 113003, Oct. 17, 1997 Held: The explosion of a new tire cannot by itself beconsidered a fortuitous event to exempt the commoncarrier from liability in the absence of showing on thepart of the carrier that other human factors that couldhave intervened to cause the blowout of the new tire did not in fact occur. Moreover, a common carrier may not be absolvedfrom liability in case of force majeure or fortuitous event alone. It must still prove that it was notnegligent in causing the death or injury resultingfrom the accident.

PESTANO v. SUMAUYANG, 346 SCRA 870 (2000) Held: The fact that the driver was able to use a bus with a faulty speedometer shows that theemployer was remiss in the supervision of itsemployees and in the proper care of itsvehicles. Under Arts. 2180 and 2176 of the Civil Code, owners and managers areresponsible for damages caused by theiremployees.