Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

Shuzo Kuki and Jean Paul Sartre Influence and Counter Influence in The Early History of Existential Phenomenology

Enviado por

ilookieTítulo original

Direitos autorais

Formatos disponíveis

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Shuzo Kuki and Jean Paul Sartre Influence and Counter Influence in The Early History of Existential Phenomenology

Enviado por

ilookieDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

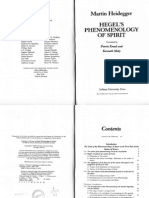

Page iii

2/693

Shuzo * Kuki and Jean-Paul Sartre

Influence And Counter-Influence In The Early History Of Existential Phenomenology

By Stephen Light Including The Notebook "Monsieur Sartre" And Other Parisian Writings Of Shuzo Kuki Edited and Translated By Stephen Light

3/693

Foreword by Michel Rybalka Published for The Journal of the History of Philosophy, Inc.

SOUTHERN ILLINOIS UNIVERSITY PRESS Carbondale and Edwardsville

title:

author: publisher: isbn10 | asin: print isbn13: ebook isbn13: language:

Shuzo Kuki and Jean-Paul Sartre : Influence and Counter-influence in the Early History of Existential Phenomenology Journal of the History of Philosophy Monograph Series Light, Stephen.; Kuki, Shuzo Southern Illinois University Press 0809312719 9780809312719 9780585033723 English

4/693

subject publication date: lcc: ddc: subject:

Kuki, Shuzo,--1888-1941, Sartre, Jean Paul,--1905- , Existential phenomenology, Time. 1987 B5244.K844L53 1987eb 181/.12 Kuki, Shuzo,--1888-1941, Sartre, Jean Paul,--1905- , Existential phenomenology, Time.

Page iv

For Tetsuo Kogawa and Osamu Mihashi Copyright 1987 by The Journal of the History of Philosophy, Inc. All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America Edited by Curtis L. Clark Designed by Cindy Small Production supervised by Natalia Nadraga Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

6/693

Light, Stephen, date Shuzo Kuki and Jean-Paul Sartre: influence and counter-influence in the early history of existential phenomenology. (The Journal of the history of philosophy monograph series) "Including the notebook 'Monsieur Sartre' and other Parisian writings of Shuzo Kuki, edited and translated by Stephen Light." Bibliography: p. Includes index. 1. Kuki, Shuzo *, 1888-1941. 2. Sartre, Jean Paul, 1905- 3. Existential phenomenology. I. Kuki, Shuzo, 1888-1941. II. Title. III. Series. B5244.K844L53 1987 181'.12 86-11861 ISBN 0-8093-1271-9 (pbk.)

7/693

CONTENTS

The Journal of the History of Philosophy Monograp Foreword Michel Rybalka Preface Richard H. Popkin Acknowledgments

Part One Shuzo Kuki and Jean-Paul Sartre: Influence and Co of Existential Phenomenology Stephen Light

9/693

Part Two Considerations on Time: Two Essays Delivered at P August 1928 Shuzo * Kuki

The Notion of Time and Repetition in Oriental Tim The Expression of the Infinite in Japanese Art

Part Three Propos on Japan Shuzo * Kuki Bergson in Japan Japanese Theater A Peasant He Is The Japanese Soul Time Is Money In the Manner of Herodotus Subject and Graft Geisha Two Scenes Familiar to Children General Characteristics of French Philosophy

11/693

Part Four "Monsieur Sartre": A Notebook Shuzo Kuki Bibliography Index

Page vii

THE JOURNAL OF THE HISTORY OF PHILOSOPHY MONOGRAPH SERIES

THE JOURNAL OF THE HISTORY OF Philosophy Monograph Series, consisting of volumes of 80 to 120 pages, attempts to accommodate serious studies in the history of philosophy that are between article length and standard book size. Editors of learned journals have usually been able to publish such studies only by truncating them or by publishing them in sections. In this series, the Journal of the History of Philosophy will present, in volumes published by Southern Illinois University Press, such works in their entirety.

13/693

The historical range covered by the Journal of the History of Philosophy Monograph Series will be the same as that covered by the Journal itselfthe range from ancient Greek philosophy to that of the twentieth century. We anticipate including extended studies on given philosophers, ideas, and concepts, as well as analyses of texts or controversies and new documentary findings about various thinkers and events in the history of philosophy. The editors of the Monograph Series, Richard H. Popkin and Richard A. Watson, will draw upon the directors of the Journal of the History of Philosophy and other qualified experts to evaluate submitted manuscripts.

14/693

We believe that a series of studies of this size and format will fulfill a genuine need of scholars in the history of philosophy, and we hope to present important new studies and texts to the scholarly community.

Page ix

FOREWORD

IT WAS GENERALLY KNOWN, THROUGH Simone de Beauvoir and Fernando Gerassi, that Jean-Paul Sartre had had substantial talks in the late twenties with an unnamed Japanese philosopher who had just met Heidegger in Germany, and that, later on, Sartre had tried unsuccessfully to obtain an assistantship in Japan. In 1966, during Sartre's stay in that country, it was learned from him that his interlocutor was indeed the philosopher Shuzo * Kuki, also known as Baron Kuki because of his aristocratic descent. This intriguing East-West encounter remained, however, a mystery; when I investigated it in France a few years ago, I was unable to come up with any precise information.1

16/693

Then, a miracle of research happened: Stephen Light, a young American scholar from Berkeley, helped by his knowledge of French, by his Japanese wife, and by his passion for philosophy, gained access, thanks to Professor Akio Sato, to Kuki's papers, among which was a notebook marked "Monsieur Sartre." This notebook contained a series of brief notes on French philosophy, and lo and behold! one page was in the handwriting of Sartre himself, thus giving an unforeseen dimension to the whole document.

17/693

In his well-researched introduction, Stephen Light provides all necessary information about the life and works of Baron Kuki and states that Kuki had weekly talks with Sartre during two and a half months in 1928, very likely from September to November. These dates can be confirmed from what we know of Sartre's schedule: in June 1928, he took the strenuous examinations for the agrgation de philosophie and failed because he had attempted to develop a line of thinking which was considered too personal; he had some vacations with his friend Nizan in August, and returned to Paris towards the end of the summer, being thus free for his talks with Kuki.

18/693

We know from the notebook what Sartre, more or less, said to Kuki, or at least we are able to read what Kuki found useful to jot down in a sometimes faulty French. It is likely that the experienced Kuki asked the young Sartre (who was then twenty-three) to tell him about the present state of French

Page x

philosophy, and that Sartre, fresh from the comprehensive preparation needed for agrgation,was happy to oblige, happy to make some money and to communicate his own personal ideas and preferences. Sartre, for instance, mentions an article by his former professor of philosophy at the Lyce Louis-le-Grand, Colonna d'Istria, and introduces remarks on communists and radical-socialists. The presence of names like Proust, Valry, and Breton associated with names like Nietzsche, Alain, and Bergson shows clearly the importance that Sartre was already attributing to the connection between philosophy and literature. Several pages are devoted to Descartes, Pascal, Valry, but no mention is made of Freud or Marx.

20/693

A comparison of Kuki's notes with his rather positivistic texts (to be found later in this volume) on the general characteristics of French philosophy or on Bergson clearly reveal, in my opinion, the difference between the Japanese philosopher and Sartre. It is striking, for instance, that the page in Sartre's handwriting insists on negation and proposes, as it appears, a dialectical approach to the problem of being and nothingness. The words "Premire solution: Esthtisme" linked to "pessimisme" refer already to a major theme in Sartre's literary philosophy, and especially to his studies of Baudelaire, Genet, Mallarm, and Flaubert.

21/693

Kuki's notes can certainly be read as an abbreviated text by Sartre (or as an interview), but it would be difficult to find in them a central unifying vision or a clear delineation of what Sartre's philosophy will become later. In this respect, texts written by Sartre in 1927-28such as his diplme d'tudes suprieures thesis on the image, such as his novel Une dfaite (where Sartre sees himself in the situation of Nietzsche in his relationship with Richard and Cosima Wagner), such as the recently discovered essay "Er l'Armnien," based on book 10 of Plato's Republicprovide a much richer, a more explicit and more original material. 2

22/693

Was there a meaningful dialogue between Sartre and Kuki? Was Sartre influenced by Kuki? To my knowledgebut this is to be verifiedthere is no written trace in Sartre's manuscripts of his encounter with the Japanese philosopher. In his mature life, Sartre repeated time and again that he thought that discussions among philosophers were futile and unproductive and that invention in philosophy could be achieved only through writing. The difference of age and of culture, the language barrier, the apparent respect with which Kuki treated "Monsieur Sartre" were probably not conducive to an open exchange of ideas. We can surmise, however, that Kuki explained to Sartre what he had heard about phenomenology in Germany and that this explanation had some importance in Sartre's further development.

Page xi

It is obvious today that the discovery of phenomenology by Sartre is not the simple affair related by Simone de Beauvoir in her memoirs. Much before the famous meeting (in 1932) with Raymond Aron in front of a peach cocktail, Sartre displayed in several of his early writings a strong predisposition to phenomenology and an acute sensitiveness to what will be defined later as "existentialist" themes. On the other hand, we know that the painter Fernando Gerassi, who had studied philosophy in German universities, had told Sartre specifically about phenomenology and about Husserl and Heidegger when he met him in 1929. Thus, Shuzo * Kuki is without a doubt an early and important link in Sartre's progress toward a philosophy of freedom: through Kuki's notebook, we learn that in 1928 already people were in a "triste et neurasthnique" state of mind, but that finally, "il faut croire la libert."

24/693

It would be unjust (some would say europocentric) to limit Kuki to his encounter with Sartre. He is obviously a major figure in Japanese philosophy, and we should be grateful to Stephen Light for introducing us to his work. MICHEL RYBALKA

Notes

1. The extensive biography of Sartre by Annie Cohen-Solal, published in October 1985 by Gallimard, does not mention this episode at all. 2. The text of Une dfaite and of "Er l'Armnien," edited by Michel Contat and me, will be published in 1986 by Gallimard in a volume entitled Les Ecrits de jeunesse de Sartre.

25/693

Page xiii

PREFACE

27/693

WHEN STEPHEN LIGHT FIRST TOLD ME of the relationship between Jean-Paul Sartre and Shuzo * Kuki, and of the existence of Kuki's notebook of conversations with Sartre, I thought it was an interesting historical curiosity that deserved to be explored, and I encouraged him to do so. (Light is married to Naoko Haruta, a Japanese artist, and through her he was able to make contact with the Japanese academicians who have given him Kuki's notebook, plus much additional information.) When he sent me the first draft of his paper, along with a photocopy of the notebook, I was truly amazed at the cross-cultural relationships involved, and at the role Baron Kuki of Japan, studying in Germany and France, played in bringing Sartre first into contact with Heidegger's and Husserl's thought, and then introducing Sartre to Heidegger. Later, when Light sent me copies of the talks and writings Kuki produced in France at the time, I realized there was more here than could be

28/693

contained in one article. Yet it all had to be read together to appreciate the picture of an intellectual explosion taking place as a result of the Sartre and Kuki meeting in 1928. The conclusions that flow from Light's account seemed to me so revolutionary and important that I suggested he send his original draft to several specialists in existentialist and phenomenological thought for their reaction. They all expressed amazement and excitement about what he had found. My colleague, Michel Rybalka, who has devoted so much time and energy to Sartre scholarship, then agreed to write a foreword.

29/693

In considering what form of publication to recommend to Light, I realized the material he had put togetherhis article, the Kuki-Sartre notebook, and Kuki's French talks and writings of 1928was too much for a single journal article, yet too little for a conventional book. It occurred to me that sometimes scholars cannot condense their findings to 30-40 pages of journal printing and would be stretching their material to expand it to the conventional 200 pages for a book. What was needed was something between these

Page xiv

two extremes: a monograph size roughly 80 to 120 pages for certain kinds of presentations. At the 1984 meeting of the Board of Directors of the Journal of the History of Philosophy,I presented a plan for such a monograph series to include Light's work, a study on Hume that will follow, and other such writings. The Board agreed to commence such a series, and so I am happy to present its first volume.

31/693

This particular study, presenting an important discovery about the history of modern philosophy, provides an excellent beginning for the Journal of the History of Philosophy Monograph Series. Not only is it a fine piece of work in its own right, it also should make us aware of currents of influence that do not fit into preconceived modes. We are too used to studying developments of philosophical movements primarily in terms of antecedents within their own cultures, or in terms of influences of adjacent cultures. Stephen Light's findings should make us aware that more distant cultural meetings can and do occur, and may have significant consequences in the history of thought. Perhaps once we assimilate the significance of the tale told by Light, we can explore what has obviously been happening through European colonization and imperialism and through the dislocation of intellectuals caused by wars, revolutions, and tyrannies, as well as by the spirit of

32/693

adventure, and find many more cases in which such unexpected cross-cultural fertilization has occurred. It is a genuine pleasure to have been able to encourage Stephen Light and to work with him and with my colleagues Richard A. Watson and Michel Rybalka in arranging this monograph series and bringing this volume to fruition. RICHARD H. POPKIN WASHINGTON UNIVERSITY, ST. LOUIS

Page xv

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

NAOKO HARUTA, PROFESSOR AKIO SATO * and Professor Richard Popkinwithout them this book could not have appeared. Thankful that Shuzo* Kuki can today come before a new audience, I am gratefully indebted to them, and especially to Professor Richard Popkin for his gracious interest and efforts on behalf of this volume. The notebook ''Monsieur Sartre" is reproduced with the kind permission of the Shuzo Kuki Archive at Konan* University (Kobe*, Japan) and of its director, Professor Akio Sato.

Page 1

PART ONE SHUZO * KUKI AND JEAN-PAUL SARTRE INFLUENCE AND COUNTERINFLUENCE IN THE EARLY HISTORY OF EXISTENTIAL PHENOMENOLOGY

By Stephen Light

Page 3

36/693

IN JAPAN IT HAS LONG BEEN SAID THAT THE Japanese philosopher Shuzo * Kuki (1888-1941) while in France in the 1920s had engaged a French student as a language tutor. This student was said to have been a philosophy student at the Ecole Normale Suprieure, one Jean-Paul Sartre.1 The interest in this matter has, of course, rested on the role Kuki, long versed in phenomenology and fresh from meetings with and studies on Husserl in Freiburg and studies with Heidegger in Marburg, might have played in turning Sartre's attention towards German phenomenology.2 The question has been of all the more interest because Simone de Beauvoir's second volume of memoirs, La Force de l'ge,has always been taken as a definitive account of Sartre's early philosophical development, recounting as it does that Sartre's interest in phenomenology was first sparked in 1932 by Raymond Aron, who, back from studies at the French Institute in Berlin, had spoken in a caf

37/693

on the rue Montparnasse to Sartre of Husserl and phenomenology. Sartre, eager to inform himself on the subject, rushed out to purchase Emmanuel Levinas's book on Husserl and "leafed through the volume as he walked along, without even cutting the pages."3

38/693

In fact, Kuki did meet Sartre in Paris, but not exactly in the context of having engaged a language tutor. Rather Kuki, desiring a partner with whom to discuss French philosophy, was directedmost probably by Emile Brhier (1876-1952), then professor of philosophy at the Sorbonneto the student Sartre4. Sartre himself, when he was in Tokyo in 1966, confirmed this in an interview with Takehiko Ibuki. In response to Ibuki's query about his encounter with Kuki, Sartre replied that when he had been in his third or fourth year at the Ecole Normale, he and Kuki had met weekly for the two and a half months Kuki had been in Paris and had discussed French philosophy from Descartes to Bergson. Sartre also confirmed the fact that Kuki had

Page 4

in the course of their discussions brought up the subject of Heidegger and phenomenology, noting that "Kuki . . . was very enthusiastic about Heidegger." 5 Clearly then, Kuki, a number of years before Aron, had articulated for Sartre the nature of the newly emergent German philosophy. In fact, the Japanese philosopher Takehiko Kojima has noted that when Sartre, impelled by Aron, arranged to succeed Aron at the French Institute in Berlin in 1933, he traveled to Germany bearing a letter of introduction to Heidegger from Kuki.6

40/693

We have, thus, in this meeting between Shuzo* Kuki and the then youthful Jean-Paul Sartre, a remarkable circumstance, one all the more interesting, as familiarity with Kuki will soon show, because of a series of striking similarities between Kuki and Sartre. Who then was Shuzo Kuki? the Western reader will ask. Kuki was born in Tokyo in 1888, the fourth son of Ryuichi* Kuki, later Baron Kuki, one time member of the Japanese delegation in Washington, D.C. Kuki began his higher education in German law, although he had earlier exhibited an interest in botany (an interest he would sustain throughout his life). Upon entering Daiichi Kotogakko* (First Higher School)the Japanese equivalent of the (at that time) French lyce Henri-IV or lyce Louis-le-GrandKuki changed over to the humanities (bunka).7 Kuki completed his studies at Daiichi Kotogakko in 1909 and in the fall of that same year entered the philosophy department at Tokyo University. There he studied with

41/693

Raphael von Koeber (1848-1923), "Koeber Sensei,"a Russian of German extraction who had been teaching in Japan since 1893 and who had exerted influence on an entire generation of Japanese philosophy students. Graduating in 1912, Kuki began graduate studies in philosophy in the same year, subsequently finishing at Tokyo University in 1917. In 1918 he married his brother's widow, and in 1921, under the auspices of the Japanese Department of Education, he and his wife left for Europe. There he would spend the next eight years, studying first at Heidelberg, then at the Sorbonne, and later at Freiburg and Marburg.

42/693

In October of 1922 Kuki attended the neo-Kantian Heinrich Rickert's lectures "From Kant to Nietzsche: An Historical Introduction to the Problem of the Present" at Heidelberg University, and at the same time engaged Rickert as a private tutor in order to read Kant's Critique of Pure Reason.8In addition, he also studied Kant with Eugen Herrigelhimself later known for his short book based on his experiences in Japan, Zen in the Art of Archeryattendingthe German philosopher's lectures on "Kant's Transcendental Philosophy." After a trip to Switzerland and to Dresden in the spring of 1923, Kuki

Page 5

44/693

returned to Heidelberg in May 1923 and once again attended Rickert's lectures, this time the summer lectures bearing the title "Introduction to Epistemology and Metaphysics," and participated in Rickert's seminar on "The Concept of Intuition." Kuki, it should be noted, was not the only Japanese philosopher in Heidelberg at this time. He had been joined by his friend Teiyu * Amano (1888-1980), and, in addition, Jiro* Abe* (18831959), Hyoe* Ouchi* (1888-1966), Mukyoku Naruse (1885-1958), Goro* Hani (1901-), and Kiyoshi Miki (1897-1945) all were in attendance at Heidelberg.9 In fact, the German philosopher Hermann Glockner, then Rickert's assistant, would later in his memoirs speak of various Japanese philosophers in residence in Heidelberg in the early 1920s: "One day Rickert surprised me with the news that he had now decided to take on a Japanese visitor in private study: an extremely well-to-do samurai, who had asked to read the Critique of Pure

45/693

Reason with him. This gentleman, of unusually distinguished bearing, appeared entirely different from his fellow countrymen: of tall, slender figure, he had a somewhat small face, an almost European nose, and hands of extremely delicate proportion. His name was Kuki. . . ." Kuki's private study with Rickert was not without influence, albeit an indirect one, on Rickert himself. Occasioned to once again take up the later Kant, Rickert, Glockner writes, ''daily made new discoveries." "Compared to Kant," Rickert animatedly tells Glockner, "Plato is only a beginnerand Hegel and Schopenhauer have much too carelessly thrown over the fundamentals of Kantianism. All recent philosophers, insofar as they are of any use, return to Kant."10 (I cannot help but note parenthetically that Kuki, never a partisan of neo-Kantianism, would not have entirely agreed with this reassertion of the neoKantian motto.)

46/693

Kuki left Heidelberg in August 1923 and traveled to the Alps. His botanical interests having remained with him, he spent much time collecting plants, thus joining a tradition of which Rousseau and Goethe are the better known names. In the autumn of 1924 Kuki journeyed to Paris.11 There he would remain until the spring of 1927, engaged in the study of French philosophy (he would begin attending lecture courses at the University of Paris in October 1925), in the preparation of two philosophical manuscripts later to become two of his most important works, and in the composition of a series of poetic manuscripts which he would begin sending to Japan for publication.

47/693

Thus it was that Kuki in April 1925 sent a series of tankastraditional Japanese short poemsbearing the title Pari Shinkei (Spiritual Views of Paris) to the Japanese journal Myojo*where they would later be published. During the course of 1925 and 1926 Kuki sent three other series of poems,

Page 6

this time poems in open form, to the same journal, series bearing the respective titles Pari no Mado (Window on Paris), Pari Shinkei (Spiritual Views of Paris), and Pari no Negoto *(Paris Sleep-Talking).12 In December 1926 Kuki finished a manuscript, Iki no Honshitsu (The Essence of Iki), the first draft of what would later become his classic work Iki no Kozo* (The Structure of Iki), first published in 1930.13 Before leaving Paris for Freiburg in April 1927 Kuki also completed another manuscript, Oin* ni Tsuite (On Rhyming), a manuscript which would subsequently become another key work in his oeuvre, Nihonshi no Oin (Rhyming in Japanese Poetry).14

49/693

In Freiburg Kuki studied phenomenology with Oskar Becker and was able to meet a number of times with Edmund Husserl. It would be at Husserl's home that he would meet Martin Heidegger.15 Thus, in November 1927 Kuki moved to Marburg in order to attend Heidegger's lectures, "Phenomenological Investigations of Kant's Critique of Pure Reason,"as well as Heidegger's seminar, "Schelling's Treatise on the Essence of Human Freedom."In the spring of 1928 Kuki attended Heidegger's lectures on "Leibniz' Logic" and Heidegger's seminar, "Phenomenological Studies: Interpretations of Aristotle's Physics."If Heidegger's philosophy found an admirer in Kuki, Kuki in turn left a lasting impression on Heidegger.16 Years later Heidegger would pay Kuki lasting homage and would recount the discussions in which the two had engaged at his, Heidegger's, home, discussions in which Kuki had attempted to convey to Heidegger the results of his philosophical

50/693

investigations on iki.17 It was in Marburg too that Kuki became friends with another philosopher, Karl Lwith, then Heidegger's assistant. Later, in 1936, Kuki would be responsible for securing Lwith a post at Tohoku Imperial University in Sendai, a position Lwith would hold from 1936 to 1941.18

51/693

Kuki returned to Paris in June of 1928. In August he was invited by the French writer and scholar Paul Desjardinsmember along with Henri Bergson and Jean Jaurs of the famed promotion of 1878 at the Ecole Normale Suprieure and founder and organizer of the famous dcades held at Pontignyto participate in a philosophical dcade on "Man and Time. Repetition in Time. Immortality or Eternity."19 Here at Pontigny on August 11 and on August 17, 1928, Kuki delivered two lectures, one on "The Notion of Time and Repetition in Oriental Time," the other on "The Expression of the Infinite in Japanese Art." These two lectures subsequently constituted Kuki's book Propos sur le temps,published in Paris in 1928.20

52/693

The first dcade of the summer of 1928: we can imagine the setting. In the audience are Gide, Martin du Gard, the German Curtius, the Russian Berdyaev, the Englishman Strachey; hosting are Desjardins and du Bos; on

Page 7

54/693

hand to make presentations are Dominique Parodi, Emile Namer, Alexandre Koyr, Vladimir Janklvitch, and fresh from success in the agrgation, (a success his "petit camarade" Jean-Paul Sartre had not found), the youthful Raymond Aron. At the head of the room a speaker from a foreign land, in immaculate dress, is reciting in French a celebrated Japanese poem: " ' . . . where those who know and those who do not know each other meet. . . .'" The poem concluded, the speaker pauses, and then begins a commentary: "Again, an example of 'time lost' and of 'time remembered.' It is that instant when two roads meet. . . . It is the moment of a present of infinite plentitude. . . . It is the blessed moment when one soul interrogates another soul. . . . It is also this moment which we pass here in this salon in Pontigny, here where I speak to you of a verse of Semimaru, where we wonder if we might not have lived this moment before, if we might not live it again. . . Let us

55/693

leave it to our venerable blind Semimaru to meditate on the problem of chance and circular time. Let us pray that he now takes up his biwa and plays us an ancient Yamato air." At Pontigny Kuki himself offered up the harmonies of the Yamato air, presented two superb discussions of Japanese culture, discussions bearing the imprint of an erudition ranging over many aspects of Japanese art and literature; of a philosophical conception of time marked by German phenomenology that, if here only touched upon, must nevertheless have marked one of the very first, if not the first, public discussions in France of Heidegger's recent reflections on temporality in Sein und Zeit;and of an appreciation for and a mastery of just that literary culture represented by La Nouvelle Revue Franaise and that musical culture represented by French impressionism constituting the predominant orientation of his audience at Pontigny. 21

56/693

In the first essay of Propos sur le temps,Kuki aims not at a sustained analysis of time. Rather, the discussion of time aims at the vindication of that 'will' found in Bushido*(as I shall have occasion to discuss in more detail below), aims at the derivation of an ethic on the basis of contingent existence. Thus, given the ethical context, it is quite natural that Kuki finds in "anticipation" the "most important characteristic of time."22

57/693

Kuki speaks of "anticipation" in time with reference to Guyau and Heidegger (and Hermann Cohen). Guyau (1854-1888), a moral philosopher of great talent whose life was cut short at the age of thirty-three, saw in time the growth of experience. Countering the Kantian notion in which time was the condition of experience, Guyau saw in time the result of that very experience. Thus, time, being considered in this philosophy of life the "concrete order of our experience," must be analyzed not in relation to the outward world of motion, transformation, and event, but in terms of mem-

Page 8

ory, imagination, and will. 23 If then Kuki, attempting to vindicate the will in Bushido*attentive,thus, to notions tying time to the willhas felt the impact not only of Guyau's critique of Kant, but of Bergson's as well (of Bergson's critique of time as empty and homogeneous milieu), it is quite natural that he will find congenial the recent Heideggerian notion whereby in a triadic structure of ekstases past, present, and future constituting time, the essential moment of temporality is located in the future. As will become apparent more fully below, elemental in the ethic here to be derived is the motto "Let not your encounters take place in vain!"

59/693

Appropriate Western notions surveyed, Kuki turns to those oriental notions in which time is considered dependent on the will, notions found primarily in Indian texts. Thus, Kuki begins his discussion of time by writing: "If one has the right to speak of 'oriental time,' it seems it can be a question of nothing other than the time of transmigration."24 Periodic time, the "time of transmigration," poses liberation from "the wheel of time," liberation from the endless cycle of reincarnated births, as a goal. And this question of the liberation from time gives Kuki the opportunity of setting Buddhism and Bushido in opposition, an opposition which, however, is set up only in terms of "their basic tendencies." ''There cannot be the least question," Kuki writes, "of denying the great value of Buddhism." "We owe an eminent part of our oriental civilization to Buddhism." With this in mind, Kuki, to the nirvana*of Indian inspiration, to deliverance from repetitive time by

60/693

means of the intellect, by means of the denial of time, to this Buddhistic intellectualism, Kuki offers the voluntarism of Bushido: a moral idealism, an immanent, not transcendent, liberation from timean unconcern with time "in order to live, truly live, in the indefinite repetition of the arduous search for the true, the good, the beautiful."25

61/693

With the beautiful we move to the second essay contained in Propos sur le temps,"The Expression of the Infinite in Japanese Art." The beautiful, liberation par excellence from time: in moving from moral idealism to the absolute idealism of Japanese art, "the inward art of Yamato," Kuki moves from the infinite striving of the good will found in Bushido,to the sensuous expression of the infinite, from eternal striving to the "beautiful image of eternity." Here in the aesthetic realm Kuki is no longer concerned with viewing Buddhism and Bushido from the standpoint of their opposition; rather, in taking up a Japanese art of pure spirituality, he takes up an art whose nature derives from a triple source, the mysticism of Indian religion (Buddhism), the pantheism of Chinese philosophy, and Bushido, the "cult of the absolute spirit."

62/693

In referring to this "triple source," an understanding of which alone enables an understanding of Japanese art,26 Kuki, as the opening quotation

Page 9

of his essay shows, follows the analyses of Kakuzo * Okakura's sagacious introduction of Japanese art to the West, The Ideals of the East,a study, written directly in a fine and lyrical English, which appeared in 1905.27 Here Okakura poses Indian religion and Chinese philosophy as the twin pillars of one single edifice, Asian culture: Asia is one. And in this perspective it became the privilege of Japan to realize with especial clearness this "unity-in-complexity" of Asian culture. Kuki, of course, is not here concerned with the question of the unity of Asian culture. But he is concerned with the utilization of an idealist heritage. Thus, his quotation from Okakura: "The history of Japanese art becomes the history of Asiatic ideals."28

64/693

Okakura had written: "Japanese art ever since the days of the Ashikaga masters, though subjected to slight degeneration in the Toyotomi and Tokugawa periods, has held steadily to the Oriental Romantistic idealthat is to say, the expression of the spirit as the highest effort in art. This spirituality, with us, was not the ascetic purism of the early Christian fathers, nor yet the allegorical idealisation of the pseudo-renaissance. It was neither a mannerism, nor a self-restraint. Spirituality was conceived as the essence or life of a thing, the characterisation of the soul of things, a burning fire within."29 The rise of the Ashikaga shoguns to power in the middle of the fourteenth centuryinitiating, thus, the Muromachi period (1392-1573)represents an important turn: Japan's reopening of intercourse with China and the concomitant influence upon Japanese art of Sung culture and of Zen; the developments in ink painting represented above all by Sesshu*; the rise to maturity of a national

65/693

music as well as the development of No* drama. The aesthetic ideal of the period: "Beauty . . . or the life of things, is always deeper as hidden within than as outwardly expressed, even as the life of the universe beats always underneath incidental appearances. Not to display, but to suggest, is the secret of infinity."30

66/693

What for Kuki is the meaning of Japanese art? It is "the idealist expression of the infinite in the finite."31 And in his discussion of Japanese art in Propos sur le temps,Kuki in a series of detailed analyses finds in all the realms of Japanese art techniques perfectly suited for the expression of just that metaphysical and spiritual experience lying at the bottom of these arts, the liberation from space and time to be found in Indian mysticism and Chinese pantheism. The liberation from time is everywhere accomplished in Japanese poetry and music. The liberation from space is accomplished in the plastic arts, above all in ink painting, an ink painting wherein a taste for simplicity and a nostalgia for the infinite serve in the perfect realization of the very "aesthetic of suggestion" characteristic of the "inward art."

67/693

In Kuki's little Parisian volume, then, are displayed, even in a language not his own, sentiments whose flavor will be apparent in all his subsequent

Page 10

works, an "I-know-not-what" flavor which will everywhere give the reader the feeling of having been truly and genuinely charmed.

69/693

While in Paris Kuki also authored a number of short pieces akin in theme to Propos sur le temps.With these pieces we find similarity to the propos of the French philosopher Alain (nom de plume of mile Chartier [1868-1951]), a genre created by him. Early in his career Alain began writing a series of short entries for a French provincial newspaper in Rouen. Limiting himself to two pages, Alain wrote almost without stop and almost without correction. Anecdotal, aphoristic, at once philosophic and literary, the propos could be called an essay in miniature, if it were not that the very use of the word "essay" would already encroach on the sui generis character of the propos.Genre unto itself, the propos would be improperly translated if rendered "remarks," or even if rendered more formally as "considerations." In Alain's work each propos became a world unto itself, and yet each propos could become the part of a greater whole. The propos became the building block of this genuis of

70/693

French prose, the building block of each of his marvelously lucid and unified works. For Alain, "whose richness [was] thought," the propos was an ideal form, enabling him to ''spread [his thought] everywhere" (Valry).

71/693

Kuki, consummate master of a French culture of which Alain was an essential part, found his own thoughts flowing with marvelous ease into this form par excellence, the propos.Thus, we will find his propossome of which, the one on "Thtre Japonais," for example, seeming to have been written with inclusion in Propos sur le temps in mindserving as prisms through which the thoughts of Propos sur le temps (where, however, Propos signified only "remarks") are spread in renewed refraction. The piece on "Japanese Theater" carries Kuki's analysis of the expression of the infinite in Japanese art into the realm of theater; the pieces on the "Japanese Soul," and on "Two Pictures Familiar to Children," take up Kuki's discussion of moral idealism; the piece entitled "Geisha" already hints at Kuki's analysis of iki.

72/693

English translations of Propos sur le temps and Kuki's propos pieces appear in the present volume, along with translation of one other piece, Kuki's "Caractres gnraux de la philosophie franaise," originally a lecture delivered in both Japanese and French in Japan in 1930 at the Japanese-French Cultural Society. 32 Kuki's charm, his unique sensibility, can serve to highlight the sui generis place occupied by Kuki in the world of modern Japanese philosophy and letters. When Kuki ultimately returned to Japan in 1929 he received a post at Kyoto University.33 There he joined on the philosophical faculty Kitaro* Nishida (1870-1945), whom Kuki in an article on Bergson had already

Page 11

referred to as "perhaps the most profound thinker in Japan today," and Hajime Tanabe (1885-1962). 34 But even though the relations between Nishida, Kuki, and Tanabe were those of the highest mutual esteem, Kuki never belonged to the Kyoto School. Kuki, like Nishida, had assimilated Husserlian phenomenology, but unlike Nishida, he remained distant from Hegelian phenomenology. Professor Hisayuki Omodaka in speaking of the intellectualism of Nishida and the voluntarism of Tanabeand thus of the strains of speculative Indian philosophy in Nishida and Chinese practical philosophy in Tanabemarks off Kuki's philosophy by the importance there given affectivity.35 Omodaka makes particular reference to Kuki's concern with those aspects of Japanese culture such as iki and furyu*.

74/693

Mention has, of course, already been made of the element of detachment in iki. Furyu,a word made up of the characters fu*(wind) and ryu*(flowing) and designating refined elegance, also signifies a form of detachment. In a study of furyu Kuki describes the transcendent character of the "free person of furyu"as that of a "current of wind" (kaze no nagare).36But it is important to emphasize that this is not a question of an other-worldliness, nor is it a question of the extreme aestheticism of, for instance, Huysman's Des Esseintes. We do not have here the detachment of the mystic or eremite, rather we have the detachment of the flneur.And in the flneur we have in many respects Kuki himself: "I wish to contemplate (shisakusuru),to feel (kankakusuru),to yearn (shokeisuru),wandering, with a few readers, the little path between philosophy and literature, seeking fervently the eternal tranquility of truth and beauty."37 Philosophical flneur,Kuki took the "little path.'' Thus, as

75/693

the Japanese philosopher Tetsuo Kogawa has noted: "too liberal for those adhering to the Nishida-Tanabe line of Japanese idealism, . . . too artistic for those of Marxist circles, . . . he never belonged to any mainstream, right or left."38

76/693

A philosophical flneur upon the "little path"but mistake should not be made as to the nature of this flneur's contemplations. And here I may cite the rigor of thought characteristic of an earlier stroller, the original Peripatetikos*.We have in Kuki a rare combination, one in which "delicate and passionate sentiments are linked to a calm and rigorous reason." Kuki held it a "crime to fashion a veil of grey philosophy." "I am too tormented by my passions," he writes, "to live in the grey world of abstractions."39 Partisan of the Bergsonian critique of abstract rationalism ("To seize the palpitation of life, to feel the shiver of life, that is philosophy," Kuki writes), Kuki is the author of a philosophy of which may be said exactly what has elsewhere been said of Bergson's, that it "submits itself to the exigencies of language whose exactitude require a complete analysis in order to translate precisely that which resists analysis."40 Dialectical rigor, meticulous and precise, will

77/693

Page 12

animate Kuki's works, works woven with a language whose gossamer-like purity will carry in its threads the marvelous clarity of his ideas. Sublime aesthetic sentiment, the rigor of philosophical calmthese will be found forever united in the "passages" of Kuki's ouevre.

79/693

In the autumn of 1928 Kuki once again visited Henri Bergson, whom he had come to know during his first visit in Paris. At Bergson's home he met Frdric Lefevre of Les Nouvelles Littraires,to which Kuki would subsequently contribute an article on the occasion of Bergson's 1928 reception of the Nobel Prize for literature. The article Kuki contributed, "Bergson au Japon"also included in the present volumecan in certain respects be considered a philosophical self-portrait, revealing the unique development whereby Japanese philosophy was led from neoKantianism to Husserlian phenomenology by way of the Bergsonian intuition. 41

80/693

With Kuki's return to Paris, we return to his encounter with Sartre. When did they in fact meet? Several different dates have been proposed: 1925, 1926, and 1928.42 Sartre, as noted earlier, spoke of the meeting as having taken place during his "third or fourth year at the Ecole Normale," which would correspond to the academic year of either 1926-27 or 1927-28. The date of their meeting is important because if Kuki met Sartre in 1928, rather than during his earlier stay in Paris, the meeting would have been after the publication of Sein und Zeit and after Kuki's studies in Freiburg and Marburg on and with Husserl and Heideggerin other words, after Kuki's full assimilation not only of Husserlian phenomenology but also of the new hermeneutical variation represented by Heidegger.

81/693

That the date of their meeting was 1928, sometime after Kuki's return to Paris in June of 1928, is, however, something that can be determined. In Kuki's private library, unexamined until it was organized by Professor Akio Sato* in 1976 during the preparation of the Shuzo* Kuki Archive at Konan* University in Kobe*,43 a notebook of Kuki's (approximately eight by six inches in size) with brown cover bearing the heading Sarutoru-shi,that is to say, "Monsieur Sartre," was discovered. This notebook contained notes (primarily in French with a few scattered jottings in Japanese) on what were obviously the various topics Kuki and Sartre discussed during their weekly meetings referred to by Sartre in his 1966 interview in Tokyo. What is more, one of the pages of the notebook was in Sartre's own hand! Here was happy confirmation of, and hitherto unsuspected insight into, the nature of the Kuki-Sartre encounter.44

82/693

The notebook, however, carried no date on any of its pages. Indeed, outside of a few seemingly personal reminders in Japanese"which book," "typewriter," and so forth (the most interesting of which reminders was an entry, on the ninth page of the text, reading "Chartier's address," leading

Page 13

one to wonder when and if Kuki met the French philosopher Alain)there were only the thirty-five pages of entries on the philosophical discussions. Thus, it seemed that the exact date of Kuki and Sartre's meeting would as yet remain unknown. But already on the first page of entries a reference to Julien Benda's La Trahison des clercs,published in 1927, can be found, and on the fourth page of text there is reference to Andr Breton's Nadja.Thus, the riddle can be solved, for an excerpt of Nadja appeared in La Revolution Surraliste (no. 11) in March 1928, the book itself appearing later that year. Sartre and Kuki must, then, have met sometime between Kuki's return to Paris in June 1928 and his subsequent departure for Japan in December 1928.

84/693

It was noted earlier that Sartre in his interview with Takehiko Ibuki said that he and Kuki had met weekly for the "two and a half months Kuki was in Paris." The remark is, of course, inaccurate as regards Kuki's stay in Paris, for Kuki was in Paris for more than two and a half months. Yet, perhaps not so inaccurate as all that. Kuki and his wife returned to Paris, as Madame Kuki's journal shows, on the evening of May 31, 1928. From August 11, Kuki was at Pontigny for the philosophical dcade and returned to Paris, after vacationing at the French seaside, on September 6, 1928. Kuki and his wife then departed for Japan on December 9, 1928. Thus, either the period from Kuki's return to Paris the last day of May until his departure for Pontigny in August or the period from his return to Paris in September until his departure for Japan in December could correspond to Sartre's "two and a half months Kuki was in Paris." Which of these periods to choose then? Perhaps, having

85/693

just returned from fourteen months in Germany, Kuki was anxious to brush up on his French conversation skills. This would account for Emile Brhier's remark, previously cited, implying that Kuki was, in part, looking for practice in employing his French. But in view of Kuki's language skills, his previous three-year stay in Paris, and Sartre's denial that he had served as a language tutor, this does not seem altogether likely. It is more likelyand this, again, merely to attempt to give a reason for choosing the first period referred to aboveKuki simply sought to once more immerse himself in French philosophy (such version would not be inconsistent with Emile Brhier's remark). On the other hand, in the "Monsieur Sartre" notebook, reference is made to Georges Friedmann and Pierre Morhange, members of a group of young leftwing philosophers to which Sartre's lyce and now Ecole Normale companion Paul Nizan also belonged. 45 And written beside Friedmann's

86/693

name is a parenthetical note reading ''camarade de Janklvitch." As we noted earlier, Vladimir Janklvitch, substituting for his former teacher Lon Brunschvicgdetained in Pariswas, along with Kuki, one of the participants in the August 1928 philosophical dcade at

Page 14

Pontigny. 46 May we take this to mean that Kuki's notebook and, thus, his meetings with Sartre date from after Kuki's appearance at Pontigny? We might do so only if we knew for certain that Kuki had not met or come to know of Janklvitch prior to his, Kuki's, participation at Pontigny, and if we knew whether the parenthetical note was a note of Kuki's or a note based on a remark of Sartre'swhich is to say, if we knew that which cannot be fully known. Thus, we are left with the choice between the period before and the period after Kuki's visit to Pontigny.

88/693

Nonetheless, with the discovery of Kuki's "Monsieur Sartre" notebook, we are given Kuki's confirmation of Sartre's account of their meetings on French philosophy, as well as access, muffled though it may be, to these very meetings. Many of the entries in this notebooklistings of articles and books, listings of various writers and philosophers, notes on aspects of these, and so forthhave all the appearance of notes jotted down during an ongoing conversation (the entry in Sartre's hand indicates this), while others could well have been written in preparation for, or following upon, a discussion. There is, of course, no definitive way of interpreting all of the various entries in the notebook, which is to say, no definitive way of giving the content of the discussions in question. It follows, then, that there is also no definitive way of determining in every case to what (or whom) the entries ought be attributed, to a remark of

89/693

Sartre's or to a thought of Kuki's (this for those entries appearing to come from a conversation). Of course, each entry determines its own range of possible interpretations. Here the way in which one positions the speakers in the discussion in question is crucial in determining an interpretation. How weigh the differences in age and intellectual development? Kuki was forty, Sartre twenty-three. How weigh Kuki's position as foreign visitor? Is this or that entry a function of Kuki making inquiry of, or statement to, Sartre in regard to an aspect of French philosophy or culture, or a function of Sartre seeking to inform his foreign visitor of something he, Sartre, might have felt important? Such questions could be multiplied.

90/693

Best, it seems, to imagine the several possibilities in each case; then, discarding and altering as may be necessary, arrive at an approximate picture. I shall not, of course, take up here the task of giving content to all of the discussions and entries. (And one must remember that there is no way of determining whether and how many discussions might have been omitted from entry coverage.) Rather, I would like to focus on those moments in the discussions of particular interest in regard to the significance of Kuki and Sartre's encounter. The notebook is devoted to French philosophy. And it is important, at the outset, to mention that even though French philosophy had by no means

Page 15

been ignored in JapanBoutroux, Bergson, and others having been assimilated before World War Inevertheless, French philosophy was not paid the attention of its German counterpart. It would be Kuki, in part through his lecture courses at Kyoto University on French philosophy, who upon his return to Japan, would be responsible for increasing Japanese attention in regard to this traditionlectures that can well be seen as quintessential examples of the transmission of a philosophical and cultural heritage. And in this context Kuki's notebook, with its entries on such philosophers as Brunschvicg, Alain, and Blondel, can be viewed as directly preparatory to these very lectures. 47

92/693

Sartre, as noted before, spoke of discussions on French philosophy from Descartes to Bergson. And the notebook, particularly with a number of pages containing listings of readings on, for example, Descartes, Pascal, Comte, and Maine de Biran, gives evidence of this; but the notebook also, primarily, gives significant attention to then contemporary French philosophy. Thus, and it would have been hard to imagine it otherwise, the early part of the notebook is devoted to two of the leading figures of post-World War I French philosophy, Lon Brunschvicg (1869-1944) and Alain.48 Brunschvicg was at that time, after Bergson, the most important philosophical presence in France, his major work, the two volume Le Progrs de la conscience dans la philosophie occidentale,having appeared the year previous to Kuki and Sartre's meeting. Given his position as a professor, the professor, at the Ecole Normale Suprieure, it was with Brunschvicg's philosophy that all the

93/693

normaliens of the time had to come to terms, positively or negatively as the case may have been. Paul Nizan's Les Chiens de garde,as even his Aden-Arabie before it, was of course the classical negative account, scathing and mordant, albeit from the politico-existential, not philosophical, standpoint.49 Be that as it may and in spite of our position retrospective to the developments in French philosophy initiated in part by one Bruschvicg pupil, Sartre, the remark of another distinguished pupil, Jean Hyppolite, is not without application: "Even when we reacted against his thought or sought in different directions a renovation of our intellectual perspectives, it could not escape our recognition that we had been profoundly marked by him and that beyond certain formulas, there was a spirit of Brunschvicgian philosophy to which we remained ever faithful."50 As for Alain, he was one of the central figures of French intellectual and literary life in the period between the two

94/693

wars and was a not unimportant influence on the young Sartre.51 Kuki and Sartre appear to have discussed Brunschvicg and Alain in detail. As part of this, the two French philosophers are found compared to one another in the notebook. On the first page of the notebookbeneath a

Page 16

96/693

figure in which the names Parodi and Le Senne are bracketed beside that of Hamelinis a reference to Brunschvicg's important essay 52 "L'Orientation du rationalisme," which had appeared in La Revue de Mtaphysique et de Morale in 1920. The article was Brunschvicg's response to Dominique Parodi's 1919 work La Philosophie contemporaine en France.There, Parodi, specifically targeting Brunschvicg's philosophy as exemplified, for instance, in the 1912 volume Les Etapes de la philosophie mathmatique,asks: "Must contemporary thought definitively draw back before the task of a properly philosophical systematization of nature?"53 He gave his response by way of presenting Octave Hamelin's 1907 Essai sur les lments principaux de la reprsentation as that representational form of idealism that could surmount what for Parodi was the reticent idealism, the idealism of judgment, of Brunschvicg. In "L'Orientation du rationalisme," an entry into

97/693

the orientation of Brunschvicg's rationalism and thus an excellent place to take up discussion of Brunschvicg's philosophy, Brunschvicgopposing Hamelin and behind him the finitist position of Renouvier's neo-criticism,54 the conceptualism in the Aristotelian il faut s'arrter quelque parteverywhere opposes concept and synthesis in the name of judgment and analysis. Thus, Brunschvicg states elsewhere, in a 1921 discussion of the Socit Franaise de Philosophie devoted to just this issue between Parodi and Brunschvicg:

98/693

"For the dialectician of categories who has constructed a finite and discontinuous tableau, the discovery of a new species of number, of a new kind of space, of a new model of mechanics, will result only in putting the equilibrium of the doctrine in peril. He will employ all his patience and all his ingenuity to preserve his ideal essences from dangerous contact with the diversity of the notion's aspects in order to reduce these aspects to the rank of secondary, derived forms. If, on the contrary, number and space, time and cause, are not frameworks forever fixed, but laws of indefinitely progressive activity, rational idealism will say so much the better there where synthetic idealism will say so much the worse."

99/693

For our purposes it is interesting that in just this particular discussion of the Socit Franaise de Philosophie Gabriel Marcel takes issue with Brunschvicg, arguing that if Hamelin attempts to construct being, Brunschvicg eliminates being altogether. Seeking to defend ontology on the one hand, the particular on the other, Marcel polemicizes against Brunschvicg by arguing that "what counts is to know if there is a hierarchy of planes of thought or modes of experience or categories . . . [and] if to this question one holds it necessary to respond negatively, then there can be no metaphysics, I would even say no philosophy. . . . Thought denies itself there where it

Page 17

denies being. . . ." The validity of Brunschvicg's ripostethat "to a hierarchy of concepts unfolding exterior to consciousness, as if on a painted canvas, I for my part oppose the progress of living thought, immanent to the soul in which it has taken root and which it carrys along within itself" 55cannot be our concern here. Rather, we might wonder to what degree the question of ontology, the question of being, seized upon by Marcel, might not also have emerged for Kuki in this context, leading him to bring up with Sartre just that philosophy which had so recently placed the question of being at its center. That Sartre was dissatisfied with the rationalism represented by Brunschvicg's philosophy and sought a way beyond it has already been noted. Was it here that he was first given an idea as to the philosophical tools with which he would eventually fashion his philosophical liberation?

101/693

There is, of course, little doubt that Brunschvicg's philosophy came under fire in Kuki and Sartre's discussions. The sudden reference in Kuki's notebook, in the midst of the notebook's remarks on Brunschvicg, to the aforementioned Friedmann-Morhange group (Nizan, Politzer, Guterman), as well as to surrealism and Andr Breton's Nadja, must have represented a break in the discussion of Brunschvicg, a break initiated by this very discussion and devoted to oppositional currents in French intellectual life. It does not seem inappropriate to attribute this reference to a remark of Sartre's.56 Nizan, as I have mentioned, played an important role in this philosophes group of young Marxist philosophers; his political choice served as significant reference for the young Sartre. Furthermore, surrealism together with Cline's 1932 Voyage au bout de la nuit would serve Sartre in his liberation from the classical prose style of an Alain or Valry evident in

102/693

Sartre's early work La Lgende de la vrit.In any case, it is not surprising to find reference to oppositional currents. Brunschvicg's absolutely supple thoughtNizan characterized Brunschvicg as a thinker having the "precision of a watchmaker . . . the sleight-of-hand of a conjurer . . ."57was the other side of a philosophy of culture, of a humanism of culture, which for all its magnanimity could not have represented, even in the non-Marxist Sartre's eyes, anything but an official culture.

103/693

The notebook's reference to oppositional currents in French culture is sign of a surprising political leitmotif that runs throughout the notebook's entries on both Brunschvicg and Alain. Thus, when Kuki and Sartre turn attention to Alain, it is to his Mars ou la guerre juge and to his Elments d'une doctrine radicale. Mars ou la guerre juge,Alain's brilliant condemnation of the war, appears to have been discussed quite extensively by Kuki and Sartre. The frequent references to Alain's politicshis radicalism (liberal variant) and socialismas well as a notebook entry charting all positions along the political spectrum, show that it was in a political, and not

Page 18

only ethical, context that Alain's texts were discussed. These references, together with a notebook entry detailing two forms of radicalism (now in its generic usage), one artistocratic, the other anarchistic, are all the more interesting given the relative absence of a political reflection in Kuki and given the young Sartre's studied, nuanced distance from the left-wing options to which he was, after all, inclined. We cannot, of course, find an answer to the intriguing question: How would Baron Kuki and the iconoclastic young Sartre have discussed these two forms of radicalism, aristocratic and anarchistic? But we should be reminded of what is already known: that Sartre's political history only partially lends itself to the view, thus schematic, of an apolitical young Sartre, a political postWorld War II Sartre. 58

105/693

In regard to Brunschvicg and Alain, it should also be mentioned that Sartre's undoubted opposition to their center-left politics and his evident dissatisfaction with their rationalisms of judgment ought not serve to obscure the influence, alluded to before, of Brunschvicg's philosophy, which for all that it was a philosophy of intelligence was by this very fact a philosophy of liberty; ought not obscure a more important fact, that the distinct stoic dimension in L'Etre et le nant was derived, in part, from the stoicism, however much mediated by its Cartesian and Spinozistic variants, of that stoic sage par excellence, Alain.

106/693

If for Sartre a polemical relation to Brunschvicg and Alain was in certain respects the other side of an undeniable influence,59 in the case of Kuki the fact of an already achieved intellectual independence, underscored by Kuki's implantation in another culture, would not have entailed the breaking of influences. Indeed, everything conspired to make of Alain a figure of affinity for Kuki. Kuki's valorization of the voluntarist element in Bushido* would lead him to an especial appreciation of Alain's stoic ethic, and Kuki's aesthetic sensibility could not but deepen his feeling of affinity with this philosopher who, par excellence, was un crivain,with the author of Systme des beaux-arts.

107/693

Indeed, Kuki and Sartre took up discussion of Systme des beaux-arts,perhaps the centerpiece in Alain's oeuvre. Worth nothing here are the specific references in Kuki's notebook to chapters 1 and 5 of the first section of Alain's work, chapters on the imagination. These specific references are worth noting precisely because they deal with chapters that Sartre would critically analyze in his first published book, the 1936 L'Imagination,a book in which Alain's theory of the imagination is analyzed (as a concluding example in a historical overview of theories of the imagination) and superceded by means of Husserl. That this 1936 work was the revised version of Sartre's thesis, written for his diplme at the Ecole Normale, offers the

Page 19

opportunity to wonder what type of discussion Kuki and Sartregiven Kuki's familiarity with Husserlian phenomenologyengaged in with reference to Alain's text.

109/693

Concluding their discussions of Brunschvicg and Alain, Kuki and Sartre turned their attention to another leading figure of then contemporary French philosophy, the Catholic Maurice Blondel (1861-1946), giving themselves over to a reading of Blondel's 1893 work L'Action. 60This choice is noteworthy; for these two future exponents of existential phenomenology to take up the reading of a work that in its depiction of action as, to use Louis Lavelle's phrase, "an elan by which being strives to surmount its own insufficiency" has been seen by some to have prefigured (albeit in a Catholic context where faith is the goal) notions in French existentialism. Thus, we have Blondel's "Condemned to life, condemned to death, condemned to eternity, how, and by what right, if I have neither known nor willed this?"61

110/693

The notebook contains a listing of a number of chapters of Blondel's book, presumably chapters to be read and discussed, but the notebook's page references refer only to the opening chapters of the work. Here Blondel carries out an intense polemic against a nihilist position, now dubbed aestheticism, now dubbed dilettantism, that would attempt to evade the problem of action, the condemnation to action, by "willing the nothingness of man and his acts." This solution is shown to break down because beneath every negation a love of negation is found; denial entails the constitution of denial, has a positive resolution. The nihilist's "nolont" itself "dissimulates a subjective end." '''I do not want to will,' nolo velle,is immediately translated in the language of reflection into these words, 'I want not to will,' volo nolle."It is in this context, Blondel's discussion of the aesthetic-nihilist solution, of this "volont de nant," that we find a page of the notebook in Sartre's own hand, a

111/693

schema of the aesthetic/pessimist solution and of the contradiction found at its base between, as Blondel terms it, "two divergent movements, the one bearing the will towards a grand idea, towards a noble love of being, the other giving it up to the desire, the curiosity, the obsession for the phenomenal."62 The existence of a notebook page in Sartre's hand isbeyond the immediately evident reasonsimportant, for it bears out the notion that certain of the notebook's entries were jotted down during an ongoing discussion. That just here, in the context of Blondel's critique of a "volont de nant," a page in Sartre's own hand appears is more than likely merely a matter of chance. But there is reason to wonder. In the course of his entries on Blondel, Kuki jotted down the phrase, "on nothingness, as in Bergson." Kuki had in mind, of course, Bergson's critique of the "deification of nothingness" in L'Evolution cratrice.63Nothingness, nihilism, negationKuki, it should be noted, was

112/693

Page 20

at just this time working on a paper, "Negation," begun during his participation the year before in Heidegger's seminar. 64 Would not this context have especially invited Kuki to introduce his youthful French partner to the new existential variant of phenomenology?

114/693

The discussion of Blondel gives way in the notebook to the aforementioned pages where listings of readings on Descartes, Pascal, Maine de Biran, Comte, and others are found. Various informal notes scattered among the listingsof the nature, for example, "bad translation" and "very good,"give one the feeling that Kuki may have consulted or perhaps even constituted these lists with Sartre. Following these lists the notebook moves on to Paul Valry. Earlier in the notebook, amid pages devoted to Alain, there are references to Eupalinos, L'Introduction la mthode de Leonardo di Vinci,and La Jeune Parque.In the latter part of the notebook, Kuki and Sartre give close attention to the pieces in Valry's Varit I. And here, in the context of Valry, is another intriguing feature of the KukiSartre encounter, for it is probable that in discussing this writer in whose poetics the position of the Muse was held by the Mistress Chance, Kuki and Sartre were led to a discussion of

115/693

contingency. It need hardly be mentioned the place contingency would hold in La Nausetheearly draft of which Sartre had referred to as Factum sur la contingence65aswell as in L'Etre et le nant.The young Sartre considered contingency his central philosophical intuition, as is illustrated by Simone de Beauvoir's description of Sartre's purchase of Levinas's book on Husserl: "[Sartre's] heart missed a beat when he found references to contingency. Had someone cut the ground from under his feet then? As he read on he reassured himself that this was not so. Contingency seemed not to play any very important part in Husserl's systemof which in any case Levinas only gave a formal and decidely vague outline."66

116/693

Contingency had, of course, been central to Sartre from the time of his days at the Ecole Normale. In a series of discussions with Simone de Beauvoir held in 1974 Sartre recounted that he had in his student years begun entering reflections on contingency into a notebook he had chanced (!) upon while riding the metro. Films, Sartre recalled, had been the occasion of his discovery of contingency. Exiting a movie theater, he had been struck by the contrast between the necessity of the events in films and the contingency of the comings and goings of people in the street. Contingency existed. So too, Sartre came to feel, existed an elective affinity between himself and this notion: "I found that the notion had been neglected. . . . All Marxist thought culminated in a world of necessity; there was no contingency, only determinism, dialectics; there were no contingent

Page 21

facts. . . . I thought that if I had discovered contingency in films and exits into the street, it was because I was meant to discover it. 67

118/693

We need not linger over this re-entry of necessity by way of destiny. Contingency and finality can be reconciled. Rather, what is so very interesting is that contingency occupied a central place in Kuki's own philosophy; indeed, his was precisely a philosophy of contingency.68 Contingency had been the topic of his 1932 doctoral dissertation, Guzensei*(Contingency), of which his 1935 work Guzensei no Mondai (The Problem of Contingency) was the considerable elaboration.69 Kuki's interest in contingency, however, well predated these works. He had, for example, delivered an important lecture on contingency in 1929 at Otani* University shortly after his return from Europe. And the notion was in evidence in his 1928 Propos sur le temps.In the first essay of this book, Kuki is concerned, as was noted earlier, with the derivation of an ethic on the basis of contingent existence. Setting off, in contradistinction to linear time, an oriental time, a "time of transmigration," Kuki

119/693

notes that, if the supreme evil for Buddhism lies in the perpetual repetition of the will, this is the supreme good for Bushido*. "Bushido is the affirmation of the will, the negation of the negation. The infinite good will, which can never be entirely fulfilled, which is destined always to remain deceived, must ever and always renew its efforts." Bushido says: "Let us confront transmigration fearlessly, valiantly. Let us pursue perfection with a consciousness well aware that it will remain ever deceived. . . ." Partisan of the voluntarism in Bushido,Kuki takes issue with what he sees as the Greek tendency to see in the myth of Sisyphus, for example, a myth of damnation. For Kuki there is no tragedy here, rather the possible foundation of a moral attitude: "Everything depends on the subjective attitude of Sisyphus. His good will, a will steadfast in always beginning anew, in ever rolling the rock, finds in this repetition itself a complete ethic, and, consequently, all its happiness."70

120/693

It is precisely these analyses that will reappear a number of years later and form part of Kuki's systematic treatment of contingency in Guzensei no Mondai (The Problem of Contingency). An account of this book cannot be given here. But I shall note that after a sustained analysis of contingency in its three modalitiescategorical, hypothetic, and disjunctivean analysis in which contingency is revealed as the metaphysical absolute, the arrival point of the work becomes the derivation of an ethic, the "interiorization of contingency." And here is why Kuki in Propors sur le temps valorized that Heideggerian temporality in which the meaning of time is founded on "the future as coming towards the self and passing, thereby, into the already existing past," that Heideggerian temporality in which "if possibility [is] a

Page 22

122/693

coming towards,"it is so "because the logical nature of possibility [lies] in the future"for in regard to the "interiorization of contingency" Kuki writes: "[That] 'nothing takes place in vain' signifies my future possibility of interiorizing the very thou (nanji)conditioning me. The almost impossible tiniest possibility (gokubi no kanosei *)becomes reality in contingency, and this contingency, ever giving rise to new contingencies, leads on toward necessity. Here lies the salvation of man. . . . A sense of eternal destiny can be given to contingency, containing nothingness in itself and whose destiny is ever to lose itself, only by vitalizing (ikashimuru)the present by means of the future." Thus, Kuki could bring Guzensei* no Mondai to close: "When reality is confronted with nothingness, unable to restrain our surprise we cry out with Milanda: Why? . . . To the 'why' of Milanda we can only respond that contingency is an inevitable condition of concrete reality in the domain of theory, but that

123/693

in the domain of action it is, perhaps, possible to fill the lacuna of theory if we give ourselves this order: Let not your encounters take place in vain (oute munashiku suguru nakare)."71Here in this concluding command, taken from the Buddhist Jodoron*,we find precisely that good will previously rendered to Sisyphus.

124/693

The author of a philosophy of contingency, Kuki was also the author of an aesthetic of contingency, fashioning a poeticsof which the first text was his 1927 Oin* ni Tsuite (On Rhyming)in which contingency holds central place. What, in this regard, is the function of rhyme? It is to "make of the poetic form a place of contingency, a place where, fugitively, words meet and sounds respond to one another; it is in poetry to signify symbolically the pulsation of life. . . . Thus, the full force of poetry is found where one knows how to make manifest in a precarious and fragile aesthetic form that sense of contingency which is at the heart of one's faith in language, in the spirit of words." And with contingency and rhyme we return to Kuki's notebook, for in fashioning his work on the poetics of rhyme, Kuki was influenced precisely by the poetics of Paul Valry: "From the point of view of form Paul Valry considers poetry as the pure

125/693

system of the destiny of language and speaks of the philosophical beauty possessed by rhyme."72 By what destiny, then, by what chance, this meeting between these two philosophers of contingency? We cannot, of course, know for certain whether Kuki and Sartre discussed the question of contingency, but in view of the attention paid Valry in Kuki's notebook, it seems likely. And if they did, it would carry all the more significance given Sartre's feeling of elective affinity with the philosophy of contingency and given the fact that they very certainly did discuss the philosophy of existence. Sartre, of course, could not later have read Guzensei no Mondai.Thus, only Kuki could have known of the subsequent reflections on contingency of his philosophical discussion

Page 23

partner. But a search of Kuki's library did not turn up La Nause nor any of Sartre's other prewar works. Kuki's knowledge of Sartre's subsequent development is not thereby ruled out, but it cannot, obviously, be demonstrated. 73 In any case, this "contingent" parallel remains arresting.

127/693

As for other parallels, they have already been well in evidence. Thus, if Sartre was to become the leading exponent of existential phenomenology in France, Kuki was to occupy a similar position in Japan. And Kuki's aforementioned 1933 work on Heidegger, his 1934 Jitsuzon no Tetsugaku (The Philosophy of Existence), and his 1937 Ningen to Jitsuzon (Man and Existence) were not only works representative of the existential phenomenological current in Japan, they were works that also made entry of this current into Japan possible in the singular way that in them a portion of the vocabulary of existential phenomenology, previously not existent in Japanese, was coined. Jitsuzon (existence), for example, was a word created by Kuki.74 And, then, a remaining parallel: Kuki and Sartre both divided their time between philosophy and literature, Sartre in the novel and drama, Kuki in poetry.

128/693

It remains, then, to consider Kuki's influence on Sartre, to consider the significance of their encounter. At the time of their meeting Sartre was a twenty-three-year-old student, one year away from passing the agrgation in philosophy.75 If in contingency he had already seized upon one of the central notions of his subsequent mature philosophy, he would not be in a position to systematically develop his intuitions until he had completed his apprenticeship in Husserl, Heidegger, and Hegel. Kuki, on the other hand, was forty years old, possessor of an enormous culture and, now having meditated on the lessons of German phenomenology, beginning an independent philosophical production that would make him one of the outstanding talents in modern Japanese philosophy. Sartre in his 1966 interview in Tokyo noted that if Kuki had introduced him to Heidegger's phenomenology, he, Sartre, as yet only a student, had not been in a position to take up Heidegger. As regards

129/693

Heidegger and phenomenology, then, it was Kuki's distinct role to have turned Sartre's attention to Heidegger and phenomenology, to have given Sartre an agenda,no matter that it could not be immediately attended. But what of the role given Raymond Aron in Simone de Beauvoir's La Force de l'ge? Clearly, Aron could not have introduced Sartre to phenomenology.76 But doubtless Sartre's 1932 conversation with Aron was important. That Sartre was thus impelled to make arrangements to study in Germany attests to that fact and shows that Aron had quickened the urgency of Sartre's agenda. Sartre's receptivity to phenomenology had surely increased in the years subsequent to, indeed by very virtue of, his encounter

Page 24

with Kuki. He was now better placed to hear that which Aron had to tell him. And today, with the seemingly ever-present journals of the drle de guerre,Sartre himself provides us insight into the nature of this receptivity and, what is more, offers us a way of discussing the significance of, as well as just that aforementioned destiny in, Sartre's encounter with Kukifor there at the head of an entry (of February 1940) is found: "If I want to understand the share of liberty and destiny in what is called 'undergoing an influence,' I can reflect on the influence Heidegger has exercised on me." 77

131/693

In this entry Sartre gives in a way not available before, the chronology and significance of his encounter with Heidegger. Sartre had journeyed to Berlin in the fall of 1933 with the intention of reading "the phenomenologists." Taking up first with Husserl, he plannedhaving purchased a copy of Sein und Zeit in Decemberto read Heidegger the following spring. However, he found upon commencing with Heidegger that he was "saturated with Husserl." The intense study of Husserl had exhausted him that year for philosophy. Of Sein und Zeit he was only able to read fifty pages, the difficulty of the vocabulary, in any case, putting him off.78 Sartre would find that his apprenticeship with Husserl would require four years, carrying well into 1937 the time of his composition of the never-to-be completed La Psyche (of which only the section on the emotions would ever be published). If Sartre broke off writing this work, it was because his dissatisfactions with it revealed to him his

132/693