Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

Women Entrepreneurship and Social Capital

Enviado por

api-2418961620 notas0% acharam este documento útil (0 voto)

132 visualizações16 páginasTítulo original

women entrepreneurship and social capital

Direitos autorais

© Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Formatos disponíveis

PDF, TXT ou leia online no Scribd

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoDireitos autorais:

Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Formatos disponíveis

Baixe no formato PDF, TXT ou leia online no Scribd

0 notas0% acharam este documento útil (0 voto)

132 visualizações16 páginasWomen Entrepreneurship and Social Capital

Enviado por

api-241896162Direitos autorais:

Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Formatos disponíveis

Baixe no formato PDF, TXT ou leia online no Scribd

Você está na página 1de 16

Women Entrepreneurship

and Social Capital

This anthology has been prepared

with full co-operation between the editors

Iiris Aaltio, Paula Kyr and Elisabeth Sundin

Editors

Women Entrepreneurship

and Social Capital

A Dialogue and Construction

Copenhagen Business School Press

Women Entrepreneurship and Social Capital

A Dialogue and Construction

Copenhagen Business School Press, 2008

Printed in Denmark by Narayana Press, Gylling

Cover design by BUSTOGraphic Design

Cover artwork:

Artist:

Marika Mkel

Title:

Give the Birth II

Oil and pigment on canvas, 2005/2006

Contact information:

Galleria Anhava

www.anhava.com

Email: galerie@anhava.com

First edition 2008

e-ISBN 978-87-630-9991-2

Published in cooperation with School of Economics and Business Administration

University of Tampere, Finland

Distribution:

Scandinavia

DBK, Mimersvej 4

DK-4600 Kge, Denmark

Tel +45 3269 7788

Fax +45 3269 7789

North America

International Specialized Book Services

920 NE 58th Ave., Suite 300

Portland, OR 97213, USA

Tel +1 800 944 6190

Fax +1 503 280 8832

Email: orders@isbs.com

Rest of the World

Marston Book Services, P.O. Box 269

Abingdon, Oxfordshire, OX14 4YN, UK

Tel +44 (0) 1235 465500, fax +44 (0) 1235 465655

E-mail: client.orders@marston.co.uk

All rights reserved.

No part of this publication may be reproduced or used in any form or by any means - graphic,

electronic or mechanical including photocopying, recording, taping or information storage or

retrieval systems - without permission in writing from Copenhagen Business School Press at

www.cbspress.dk

Table of Contents

Preface 9

Part I

Specics of Women`s Entrepreneurship Theory

Chapter 1 13

Introduction

Women Entrepreneurs

- Creators and Creations of Social Capital

Iiris Aaltio, Paula Kyr & Elisabeth Sundin

Chapter 2 23

Entrepreneurship in Organization

- Gender and Social Capital

Iiris Aaltio

Chapter 3 39

Gender in Entrepreneurship Research:

A Critical Look at the Literature

Camille Carrier, Pierre-Andr Julien & William Menvielle

Chapter 4 67

From Marginality to Centre Womens

Entrepreneurship Policy Challenges Governments

Gender Neutrality in Finland

Paula Kyr & Kaisa Hyrsky

6

Part II

Gendered Nature of the Social Capital

in Entrepreneurship

Chapter 5 95

Organisational Entrepreneurs in the Public Sectors

- Social Capital and Gender

Elisabeth Sundin & Malin Tillmar

Chapter 6 121

Network Credit: The Magic of Trust

May-Britt Ellingsen & Ann Therese Lotherington

Chapter 7 147

Examining the Role of Social Capital in Female Pro-

fessionals Reputation Building and

Opportunities Gathering: A Network Approach

Yuliani Suseno

Chapter 8 167

The Problematic Relationship between Social

Capital Theory and Gender Research

Helene Ahl

Table of Contents

7

Part III

Cross-Cultural Context of

Women`s Entrepreneurship

Chapter 9 193

Woman, Teacher, Entrepreneur: On Identity Construc-

tion in Female Entrepreneurs of Swedish Independent

Schools

Monica Lindgren & Johann Packendorff

Chapter 10 225

Impact of Women-Only Entrepreneurship Training in

Islamic Society

Muhammad Azam Roomi & Pegram Harrison

Chapter 11 255

Comparative Study of Women Small Business

Owners in the Americas

Terri R. Lituchy, Jo Ann Duffy, Silvia Monserrat, Suzy Fox, Ann

Gregory, Miguel R.Olivas Lujn, Betty J. Punnett, Neusa Santos,

Martha Reavley & John Miller

Authors 283

Name Index 289

Subject Index 301

Table of Contents

Preface

The origins of this book relate to the workshop held at Brussels, at the

EIASM Institute on Female managers, entrepreneurs and the social

capital of the frm`. This inspiring and IruitIul workshop proposed

Ior the frst time the idea oI creating a dialogue between women

entrepreneurship and social capital theory and research. Many oI the

articles introduced in this book originate Irom this dialogue. In the

Nordic Academy of Management Conference in Aarhus 2005 this

dialogue continued and expanded with new participants from the group

of researchers that gathers yearly together on the French governments

initiative in Dauphin University, in Paris. The shared understanding oI

these womens entrepreneurship researchers from different countries

and continents was that both the concept of entrepreneurship and social

capital are multiple and complex, but interrelated.

Encouraged by this view, we decided to compile this book edition to

demarcate this landscape of social capital as interplay between gender,

management and entrepreneurship. Thus this book seeks to contrib-

ute heuristically to the discussion between social capital and womens

entrepreneurship research. Hence it has its special place among other

womens entrepreneurship books, the number of which to our delight

has recently increased. Accordingly we hope this book will expand this

dialogue of womens entrepreneurship by strengthening them in some

respects fragmented voice of womens entrepreneurship research.

We would like to address our sincere thanks to our chapter evalua-

tors, Sinikka Vanhala and Marja-Liisa Kakkonen of Finland who evalu-

ated the articles in Part I, Nina Gunnerud Berg of Norway who was

responsible for reviewing Part II, and Raja Cherif, of Tunisia for evalu-

ating part III. Their valuable comments and ideas helped us to improve

this edition and fnalise its structure. We would also like to thank the

authors Ior their dedication and contribution in this process.

This book also started publishing collaboration between two coun-

tries; Copenhagen Business School Press in Denmark and the School

of Business and Administration at the University of Tampere in Finland

expanding also the collaboration with Helsinki School oI Economics,

Finland. We would also like to thank the entrepreneurship education

team members Sari Nyrhinen and Robert Mhekwa, who helped us all

with the editing and coordinating process and for the proof-reading

services of Virginia Mattila, Robin King and Mika Puukko. Finally as

10

always, we need to thank those institutions which broad-mindedly fore-

see the meaning and value of such projects in cherishing democracy and

equality, in this respect we own our thanks to Hme Centre oI Expertise

and the Academy of Finland, and the Research Council for Culture and

Society, Ior their fnancial support.

Iiris Aaltio Paula Kyr Elisabeth Sundin

Preface

Part I

Specics of Women`s

Entrepreneurship Theory

CHAPTER 1

Introduction

Women Entrepreneurs - Creators

and Creations of Social Capital

Iiris Aaltio, Paula Kyr & Elisabeth Sundin

This book discusses social capital as the multiple relationships between

gender and entrepreneurship. Human resources are the social capital

of an enterprise and also of business liIe. They are based on trust, and

also on expertise and values. This complexity demands knowledge and

understanding Irom diIIerent felds concerning individuals, organisa-

tions and society.

Gendered Entrepreneurs

Entrepreneurship fourishes Irom the spheres oI society and work-

liIe. Labour-markets all over the world are gender-segregated. The

proportion of women at managerial level within an organisation is lower

than within the organisation as a whole. Many international studies

relating to entrepreneurs and managers show that females continue to

be a minority as entrepreneurial and managerial decision-makers. This

is true for large enterprises as well as for owner-managerial micro-sized

frms. The nature oI the managerial jobs held by women and men differs:

Iemale managers are oIten Iound to hold human resource positions.

Whether this is because they are attracted to this area or because this is

the area open to them is a question of organisational theory and gender

theory concepts (Gherardi, 1995; Alvesson & Billing, 1994; Aaltio &

Mills, 2002). Organisations construct and are constructed by gender. By

studying organisations as sites in which gender attributes are assumed

and reproduced, we can highlight their gendered nature, thus enabling

us to gain a sensitive understanding of the issues beyond the statistics of

managerial positions. Women entrepreneurs participate in social capital

creation using their special expertise and skills.

The segregation between female and male entrepreneurship is re-

fected in the workIorce in general. The gender-label oI the felds varies

14

throughout the world, likewise the gender-segregated labour market.

Traditional occupations for women as owner-managers have been in

hairdressing, hotel and restaurant businesses and the like. Nowadays

female entrepreneurs also practise their professional expertise in other

felds such as training and consultancy. However, what remains is gen-

der-segregation and the gender-labels as such not what is actually

on the label. Females are scarce in the venture feld and in technology

management. ThereIore, when female entrepreneurs promote change,

they tend to base their innovations on social ideas. This may lead to

stereotyping claiming that women are less inclined to risk-taking,

women are carers, and women are not innovative as entrepreneurs.

Such stereotypes, however, fail to take into consideration that many of

these phenomena and concepts are constructed with men as the norm

(compare, Ior example, Ahl in this volume). They also underestimate

the importance of innovations in sectors dominated by women and

overlook the many women who are indeed active in technology and

industry. We should study these circumstances iI we are to understand

entrepreneurship or the reasons why Iemales avoid it. Entrepreneurship

is based on processes between people and the context; it is not an indi-

vidual property or a collection of peoples traits that leads them to en-

trepreneurship. This leads to an understanding oI entrepreneurship and

women entrepreneurs as creators and creations of social capital based

on relations between social actors.

Entrepreneurship nowadays is almost exclusively discussed with re-

lation to small and medium-sized frms (Fayolle, Kyr & Ulijn, 2005).

Established defnitions, like Schumpeters (1934, 1989), do not, how-

ever, restrict the concept and the phenomenon to SMEs. Entrepreneur-

ship occurs and has relevance in all kinds oI contexts. This view is

apparent in some of the articles in this volume whilst others hold the

mainstream view.

Gender perspectives and gender dimensions are, nowadays, part of

the fow oI knowledge in various disciplines such as sociology, psychol-

ogy, and anthropology. However, the position oI gender-dimensions

varies between disciplines and research felds and as such is illustrated

in this book. We are convinced that to know the meaning oI gender is

to understand its cultural dimensions in the context explored. While the

debate focusing on women as business agents are broad and burgeon-

ing, the connection between men and entrepreneurship also contributes

to our cultural knowledge in the feld.

Iiris Aaltio, Paula Kyr & Elisabeth Sundin

15

In some disciplines, studies on women entrepreneurs constitute a

subfeld, whilst in others they are integrated and in some disciplines to-

tally ignored. Essentialism continues to fgure in research on entrepre-

neurship as it does in research on management. OIten 'entrepreneurs

and 'managers are studied as the essential individual, without any

gender attributes.

Finally, although this is a book on WOMEN, male entrepreneurs are

also gendered individuals, and one should not generalise about women.

Nina Gunnerud Berg, when editing the book Entreprenrskap Kjnn,

livslop og sted` (2002), with Lene Foss, Iound that 'young male entre-

preneurs when interviewed in the late 1990s argued more or less like

the female entrepreneurs I interviewed in the late 1980`s (Berg,1994,

1997). The quote illustrates that gender is not only an essential but also

a fuid category.

Social Capital

In all of todays economies, social capital is highly valued and is also

discussed as a form of corporate capital. When human resources are

scarce, the invisible elements of human capital are often presented as

a substitute. Companies compete Ior capable managerial candidates. It

is common rhetoric that women are a resource, they are an invisible

potential for the organisation, and that female managers could even

increase the profts oI the frm. Apart Irom this rhetoric, there is

widespread scepticism Irom completely diIIerent points oI view.

Are women marched into the feld only iI there are no other viable

alternatives? Are frms open to the cultural diversities that may emerge

as a result? What can business life learn from the new traits introduced

by female managers? These questions need to be addressed through

perceptive analyses and interpretations around the issues of female

gender, management and the social capital of the frm.

As stated by Kovalainen (2005, 156-157) the elasticity of the term

social capital has led to a situation in which it is used very differently,

depending on the context and research purpose in question. Usually

political science and sociology refer to a set of norms, networks, institu-

tions and organisations through which access is gained to some actions

or power. As Coleman argues, it is embodied in relations among people

(2000, 36). In many ways trust is interlinked with social capital. Social

capital creates prosperity in societies (Fukuyama, 1999, 1995).

Keeping things together and saving society from disintegration are

popular themes of social capital and trust. In an earlier theorisation

Introduction:Women Entrepreneurs...

16

Schein (1997) defned organisational culture as an outcome of socio-

psychological processes between persons and groups that come to

integrate organisations, create collective social memory (Koistinen,

2003) and shape the social structures in any organisation. These

processes are not only intellectual but also emotional. The accumulation

of peoples knowledge, trust and emotional work are much needed in

the formulation of social capital. Social capital, developing through

economic infrastructure, can also be underlined (Bourdieu, 2005). Even

if social capital is a concept that creates images of boundaries, it is

fexible and metaphorical leading to many alterations.

The use of gendered lenses in the study of entrepreneurship adds to

our perspectives on the social-capital aspects oI society. How is change

possible? How can cultural diversity in economic life be promoted?

Entrepreneurs appear to have a special position in forming, develop-

ing and reorganising social capital in the business world. The three

concepts: gender, entrepreneurship and social capital are related in a

complex way. A choice must be made between the number oI relevant

questions and aspects iI comparison and synergy are to be possible.

Among these we fnd most interesting:

- Gendered knowledge of the social capital of entrepreneurs and owner-

managers

- Cross-cultural understanding of female entrepreneurship

- Institutional issues behind womens entrepreneurship

Structure of the Book

Knowing that trust and networks are now at the heart of social capital,

how does the question of female entrepreneurs come in? Do we consti-

tute social capital differently and if so, how? In the following chapters

prominent researchers from various parts of the world and from differ-

ent academic traditions present empirical fndings as well as theoreti-

cal refections on the main themes oI the book. As a consequence the

main concepts, social capital, entrepreneurship and gender are given

diIIerent meanings. We consider this a strength, not a problem, as the

multi-meaning refects an important discussion which can be explicated

heuristically through related concepts. Since diIIerences between the

authors are also seen in the spelling and use of the English language,

we have chosen to let the authors themselves decide on their linguistic

styles.

Iiris Aaltio, Paula Kyr & Elisabeth Sundin

Você também pode gostar

- Nusacc NgaDocumento5 páginasNusacc Ngaapi-241896162Ainda não há avaliações

- Cbsreflects Genderequality Report 2014aDocumento43 páginasCbsreflects Genderequality Report 2014aapi-241896162Ainda não há avaliações

- Columbia Uni Careers Womensept08Documento18 páginasColumbia Uni Careers Womensept08api-241896162Ainda não há avaliações

- Power Shift Women and Finance AgendaDocumento10 páginasPower Shift Women and Finance Agendaapi-241896162Ainda não há avaliações

- Many Cultures One Humanity Ministerial-Declaration-Sept-25-2013-FinalDocumento3 páginasMany Cultures One Humanity Ministerial-Declaration-Sept-25-2013-Finalapi-241896162Ainda não há avaliações

- Kritikos Presentation Aom BostonDocumento17 páginasKritikos Presentation Aom Bostonapi-241896162Ainda não há avaliações

- Bac Publicartwalk-1 FullDocumento2 páginasBac Publicartwalk-1 Fullapi-241896162Ainda não há avaliações

- Entrepreneur Middle East Sept14Documento47 páginasEntrepreneur Middle East Sept14api-241896162Ainda não há avaliações

- Women Development and The UnDocumento4 páginasWomen Development and The Unapi-241896162Ainda não há avaliações

- Gender Case For WomenDocumento20 páginasGender Case For Womenapi-241896162Ainda não há avaliações

- Women Development and The UnDocumento4 páginasWomen Development and The Unapi-241896162Ainda não há avaliações

- Msu Railway EdDocumento4 páginasMsu Railway Edapi-241896162Ainda não há avaliações

- Yellen Speech Feb 11Documento7 páginasYellen Speech Feb 11ZerohedgeAinda não há avaliações

- Women As Agents of Change-Coleman RobbDocumento13 páginasWomen As Agents of Change-Coleman Robbapi-241896162Ainda não há avaliações

- Gem Aom PDW Kelley Et Al 8-4-12Documento27 páginasGem Aom PDW Kelley Et Al 8-4-12api-241896162Ainda não há avaliações

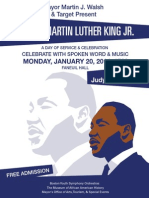

- MLK Day 2013-Self MailerDocumento6 páginasMLK Day 2013-Self Mailerapi-241896162Ainda não há avaliações

- White House Proc MLKDocumento2 páginasWhite House Proc MLKapi-241896162Ainda não há avaliações

- Railcamp PackageDocumento18 páginasRailcamp Packageapi-241896162Ainda não há avaliações

- The Treaty of Amsterdam The Next Step Towards Gender EqualityDocumento34 páginasThe Treaty of Amsterdam The Next Step Towards Gender Equalityapi-241896162Ainda não há avaliações

- MLK Jan10 tcm3-29993Documento1 páginaMLK Jan10 tcm3-29993api-241896162Ainda não há avaliações

- Irelauch Media Kit 2013w ChangesDocumento3 páginasIrelauch Media Kit 2013w Changesapi-241896162Ainda não há avaliações

- Intl Day of The Girl n1146902Documento2 páginasIntl Day of The Girl n1146902api-241896162Ainda não há avaliações

- Womens Economic Empowerment Program Fact SheetDocumento1 páginaWomens Economic Empowerment Program Fact Sheetapi-241896162Ainda não há avaliações

- JudyrichardsonbioDocumento1 páginaJudyrichardsonbioapi-241896162Ainda não há avaliações

- Ion Statusreport 2013 FinalDocumento2 páginasIon Statusreport 2013 Finalapi-241896162Ainda não há avaliações

- Take The Lead Webinars and Workshops InfoDocumento1 páginaTake The Lead Webinars and Workshops Infoapi-241896162Ainda não há avaliações

- Little WomenDocumento567 páginasLittle Womenapi-241896162Ainda não há avaliações

- Diaglogues Refugee Women 511d160d9Documento44 páginasDiaglogues Refugee Women 511d160d9api-241896162Ainda não há avaliações

- TTN Fact Sheet 2011 9 26 11Documento2 páginasTTN Fact Sheet 2011 9 26 11api-241896162Ainda não há avaliações

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeNo EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (5794)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingNo EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (399)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItNo EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceNo EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (895)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)No EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Nota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (98)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryNo EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (231)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureNo EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (474)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnNo EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (234)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerNo EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (271)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersNo EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (344)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaNo EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (266)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaNo EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (45)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyNo EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (2219)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreNo EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)No EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Nota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (120)

- Brekeke Tutorial DialplanDocumento22 páginasBrekeke Tutorial DialplanMiruna MocanuAinda não há avaliações

- Understanding the Doctrine of Volenti Non Fit InjuriaDocumento14 páginasUnderstanding the Doctrine of Volenti Non Fit InjuriaRishabh BhandariAinda não há avaliações

- Topic 2Documento9 páginasTopic 2swathi thotaAinda não há avaliações

- Chap 010Documento147 páginasChap 010Khang HuynhAinda não há avaliações

- Abraca Cortina Ovelha-1 PDFDocumento13 páginasAbraca Cortina Ovelha-1 PDFMarina Renata Mosella Tenorio100% (7)

- Welcome To All of You..: Nilima DasDocumento16 páginasWelcome To All of You..: Nilima DasSteven GarciaAinda não há avaliações

- Platinum Plans Phils. Inc Vs Cucueco 488 Scra 156Documento4 páginasPlatinum Plans Phils. Inc Vs Cucueco 488 Scra 156Anonymous b7mapUAinda não há avaliações

- Ijcisim 20Documento13 páginasIjcisim 20MashiroAinda não há avaliações

- Esaote MyLab70 Service Manual PDFDocumento206 páginasEsaote MyLab70 Service Manual PDFPMJ75% (4)

- CBM4Documento11 páginasCBM4Nathalie CapaAinda não há avaliações

- RBT-25/B Spec SheetDocumento2 páginasRBT-25/B Spec SheetSrpskiAinda não há avaliações

- P55-3 Rvge-17 PDFDocumento4 páginasP55-3 Rvge-17 PDFMARCOAinda não há avaliações

- English Form 01Documento21 páginasEnglish Form 01setegnAinda não há avaliações

- Kumba Resources: Case StudiesDocumento12 páginasKumba Resources: Case StudiesAdnan PitafiAinda não há avaliações

- Automation Studio User ManualDocumento152 páginasAutomation Studio User ManualS Rao Cheepuri100% (1)

- Komputasi Sistem Fisis 4Documento5 páginasKomputasi Sistem Fisis 4Nadya AmaliaAinda não há avaliações

- Maslows TheoryDocumento9 páginasMaslows TheoryPratik ThakkarAinda não há avaliações

- Distillation TypesDocumento34 páginasDistillation TypesJoshua Johnson100% (1)

- Amgen PresentationDocumento38 páginasAmgen PresentationrajendrakumarAinda não há avaliações

- Surface Additives GuideDocumento61 páginasSurface Additives GuideThanh VuAinda não há avaliações

- Oscilloscope TutorialDocumento32 páginasOscilloscope TutorialEnrique Esteban PaillavilAinda não há avaliações

- Basic Terms of AccountingDocumento24 páginasBasic Terms of AccountingManas Kumar Sahoo100% (1)

- D-Lux Railing System by GutmannDocumento24 páginasD-Lux Railing System by Gutmannzahee007Ainda não há avaliações

- Process Flow Diagram (For Subscribers Who Visits Merchant Business Premises)Documento2 páginasProcess Flow Diagram (For Subscribers Who Visits Merchant Business Premises)Lovelyn ArokhamoniAinda não há avaliações

- Tugas Kelompok Pend.b.asing 3Documento5 páginasTugas Kelompok Pend.b.asing 3Akun YoutubeAinda não há avaliações

- IGBC Certified BldgsDocumento26 páginasIGBC Certified BldgsNidhi Chadda MalikAinda não há avaliações

- IBP Cable and Pressure Transducers IncavDocumento6 páginasIBP Cable and Pressure Transducers Incaveng_seng_lim3436Ainda não há avaliações

- Characteristics: EXPERIMENT 08: SPICE Simulation of and Implementation For MOSFETDocumento11 páginasCharacteristics: EXPERIMENT 08: SPICE Simulation of and Implementation For MOSFETJohnny NadarAinda não há avaliações

- Chapter 3Documento2 páginasChapter 3RoAnne Pa Rin100% (1)

- Wolf Marshall's Guide To C A G E DDocumento1 páginaWolf Marshall's Guide To C A G E Dlong_tu02Ainda não há avaliações