Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

Medicine Walk by Richard Wagamese

Enviado por

Random House of CanadaDireitos autorais

Formatos disponíveis

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Medicine Walk by Richard Wagamese

Enviado por

Random House of CanadaDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

MEDICINE WALK RICHARD WAGAMESE

McCLELLAND & STEWART

Copyright 2014 Richard Wagamese All rights reserved. The use of any part of this publication reproduced, transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, or stored in a retrieval system, without the prior written consent of the publisher or, in case of photocopying or other reprographic copying, a licence from the Canadian Copyright Licensing Agency is an infringement of the copyright law. Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication Wagamese, Richard, author Medicine walk / Richard Wagamese. Issued in print and electronic formats. ISBN 978-0-7710-8918-3 (bound).--ISBN 978-0-7710-8920-6 (html) I. Title. ps8595.a363m44 2014 c813'.54 c2013-903001-8 c2013-903002-6 This is a work of ction. Any similarity between the characters in this book and persons living or dead is purely coincidental. Lines from the poem A Sort of Song are taken from Early Poems by William Carlos Williams, Dover Thrift Editions, 1997. Reprinted by permission of the publisher. Cover image: Paul D. Andrews/Flickr/Getty Images Cover design: CS Richardson Text design: Leah Springate Typeset by Erin Cooper Printed and bound in the United States of America McClelland & Stewart, a division of Random House of Canada Limited, a Penguin Random House Company One Toronto Street Suite 300 Toronto, Ontario m5c 2v6 www.randomhouse.ca 1 2 3 4 5 18 17 16 15 14

For my sons, Joshua Richard Wagamese and Jason Schaffer.

Let the snake wait under his weed and the writing be of words, slow and quick, sharp to strike, quiet to wait, sleepless. through metaphor to reconcile the people and the stones. William Carlos Williams, A Sort of a Song

he walked the old mare out of the pen and led her to the gate that opened out into the eld. There was a frost from the night before, and they left tracks behind them. He looped the rope around the middle rail of the fence and turned to walk back to the barn for the blanket and saddle. The tracks looked like inkblots in the seeping melt, and he stood for a moment and tried to imagine the scenes they held. He wasnt much of a dreamer though he liked to play at it now and then. But he could only see the limp grass and mud of the eld and he shook his head at the folly and crossed the pen and strode through the open black maw of the barn door. The old man was there milking the cow and he turned his head when he heard him and squirted a stream of milk from the teat. Get ya some breakfast, he said. Ate already, the kid said. Better straight from the tit. Theres better tits. The old man cackled and went back to the milking. The kid stood a while and watched and when the old man started to whistle he knew thered be no more talk so he walked to the tack room. There was the smell of leather, liniment, the dry dust air of feed, and the low stink of mould and manure.

1

medicin e walk

He heaved a deep breath of it into him then yanked the saddle off the rack and threw it up on his shoulder and grabbed the blanket from the hook by the door. He turned into the corridor and the old man was there with the milk bucket in his hand. Got any loot? Some, the kid said. Enough. Aint never enough, the old man said and set the bucket down in the straw. The kid stood there looking over the old mans shoulder at the mare picking about through the frost at the grass near the fence post. The old man fumbled out his billfold and squinted to see in the semi-dark. He rustled loose a sheaf of bills and held them out to the kid, who shufed his feet in the straw. The old man shook the paper and eventually the kid reached out and took the money. Thanks, he said. Get you some of that diner food when you hit town. Bettern the slop I deal up. Shes some good slop though, the kid said. Its fair. Me, I was raised on oatmeal and lard sandwiches. Least we got bacon and I still do a good enough bannock. That rabbit was some good last night, the kid said and tucked the bills in the chest pocket of his mackinaw. Itll keep ya on the trail a while. Hes gonna be sick. You know that, dontcha? The old man xed him with a stern look and pressed the billfold back into the bib of his overalls. I seen him sick before. Not like this. I can deal with it. Gonna have to. Dont expect it to be pretty.

Never is. Still, hes my dad. The old man shook his head and bent to retrieve the bucket and when he stood again he looked the kid square. Call him what you like. Just be careful. He lies when hes sick. Lies when he aint. The old man nodded. Me, I wouldnt go. Id stick with what I got whether he called for me or not. What I got aint no hell. The old man looked around at the fusty barn and pursed his lips and squinted. Shes ripe, shes ramshackle, but shes ours. Shes yours when Im done. Thats moren he ever give. Hes my father. The old man nodded and turned and began to stump away up the corridor. He had to switch hands on the pail every few steps, and when he got to the sliding door at the other end he set it down and hauled on the timbers with both hands. The light slapped the kid hard and he raised a hand to shade his eyes. The old man stood framed in the blaze of morning. That mare aint much for cold. You gotta ride her light a while. Then kick her up. Shell go, he said. Is he dying? Cant know, the old man said. Didnt sound good but then, me, I gure hes been busy dying a long time now. He turned in the hard yellow light and was gone. The kid stood there a moment, watching, and then he turned and walked back through to the pen and nickered at the horse. It raised its head and shivered, and the kid saddled her quickly and mounted and they walked off slowly across the eld.

medicin e walk

The bush started thin where the grass surrendered at the edge of the eld. There were lodgepole pines and rs where the land was atter, but when it arched up in a swell that grew to mountain there were ponderosa pines, birch, aspen, and larch. The kid rode easily, smoking and guiding the horse with his knees. They edged around blackberry thickets and stepped gingerly over stumps and stones and the sore-looking red of fallen pines. It was late fall. The dark green of r leaned to a sullen greyness, and the sudden bursts of colour from the last clinging leaves struck him like the are of lightning bugs in a darkened eld. The horse nickered, enjoying the walk, and for a while the kid rode with his eyes closed trying to hear creature movement farther back in the tangle of bush. He was big for his age, raw-boned and angular, and he had a serious look that seemed culled from sullenness, and he was quiet, so that some called him moody, pensive, and deep. He was none of those. Instead, hed grown comfortable with aloneness and he bore an economy with words that was blunt, direct, more a mans talk than a kids. So that people found his silence odd and they avoided him, the obdurate Indian look of him unnerving even for a sixteen-year-old. The old man had taught him the value of work early and he was content to labour, nding his satisfaction in farm work and his joy in horses and the untrammelled open of the high country. Hed left school as soon as he was legal. He had no mind for books and out here where he spent the bulk of his free time there was no need for elevated ideas or theories or talk and if he was taciturn he was content in it, hearing symphonies in wind across a ridge and arias in the screech of hawks and eagles, the huff of grizzlies and the pierce of a wolf call against the unblinking eye of the moon. He was Indian. The old man

said it was his way and hed always taken that for truth. His life had become horseback in solitude, lean-tos cut from spruce, res in the night, mountain air that tasted sweet and pure as spring water, and trails too dim to see that he learned to follow high to places only cougars, marmots, and eagles knew. The old man had taught him most of what he knew but he was old and too cramped up for saddles now and the kid had come to the land alone for the better part of four years. Days, weeks sometimes. Alone. Hed never known lonely. If he put his head to it at all he couldnt work a denition for the word. It sat in him undened and unnecessary like algebra; land and moon and water summing up the only equation that lent scope to his world, and he rode through it eshed out and comfortable with the feel of the land around him like the refrain of an old hymn. It was what he knew. It was what he needed. The horse stepped up and he let her have her head and she trotted through the trees toward the creek that cut a southwest swath along the belly of a ravine. She was a mountain horse. It was why hed picked her from the other three they kept. Surefooted, dependable, not prone to spook. When they got to the creek she walked in and bent her head to drink and he sat and rolled a smoke and looked for deer sign. The sun was creeping over the lip of the mountain and it would soon be full morning in the hollow. It was a days ride to the mill town at Parsons Gap and he gured to cut some time by going directly over the next ridge. There was a deer trail that snaked around it and hed follow that and let the horse pick her pace. Hed ridden her there a dozen times and she knew the smell of cougar and bear so he was content to let her walk while he sat and smoked and watched the land.

medicin e walk

When shed taken her ll he backed her out of the creek and turned her north to the trailhead. She followed the trail easily, the memory of warm livery, oats and fresh straw, and the sour apples the kid brought her before bedding down beside her for the night urging her forward, and the kid sat in the pitch and sway and roll of her, smoking and singing in a rough, low voice, wondering about his father and the reason hed been called.

Você também pode gostar

- The Pot That Was Cracked and Other Ancient Teaching StoriesNo EverandThe Pot That Was Cracked and Other Ancient Teaching StoriesNota: 5 de 5 estrelas5/5 (1)

- Chameleon Mountain - The Forbidden Love that Started a DynastyNo EverandChameleon Mountain - The Forbidden Love that Started a DynastyAinda não há avaliações

- Blue Mercy: A Heartbreaking, Page-Turning Irish Family DramaNo EverandBlue Mercy: A Heartbreaking, Page-Turning Irish Family DramaNota: 2 de 5 estrelas2/5 (5)

- Pukka's Promise: The Quest for Longer-Lived DogsNo EverandPukka's Promise: The Quest for Longer-Lived DogsNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (17)

- Mail Order Bride: Emma Travels To Her Arizona Rancher, Malory, By Oxcart (A Clean Western Historical Cowboy Romance)No EverandMail Order Bride: Emma Travels To Her Arizona Rancher, Malory, By Oxcart (A Clean Western Historical Cowboy Romance)Ainda não há avaliações

- On A Hill Far AwayDocumento5 páginasOn A Hill Far AwayCristina Martins ValenteAinda não há avaliações

- Rosie The African Elephant by Janet KaschulaDocumento28 páginasRosie The African Elephant by Janet KaschulaAustin Macauley Publishers Ltd.100% (2)

- Twain TextDocumento3 páginasTwain Textapi-337652134Ainda não há avaliações

- The ScriptureDocumento3 páginasThe ScriptureiskanicAinda não há avaliações

- A Worn PathDocumento7 páginasA Worn Pathopenid_7ps3GfWPAinda não há avaliações

- Wide Reading Assignment 2Documento3 páginasWide Reading Assignment 2Ahmed AslamAinda não há avaliações

- The Tree of Story by Thomas Wharton (Excerpt)Documento27 páginasThe Tree of Story by Thomas Wharton (Excerpt)Random House of CanadaAinda não há avaliações

- Ruby Redfort Codebreaking Activity KitDocumento7 páginasRuby Redfort Codebreaking Activity KitRandom House of Canada100% (1)

- Beyond Magenta by Susan Kuklin Discussion GuideDocumento5 páginasBeyond Magenta by Susan Kuklin Discussion GuideRandom House of CanadaAinda não há avaliações

- SHH! We Have A Plan Activity KitDocumento2 páginasSHH! We Have A Plan Activity KitRandom House of Canada100% (4)

- Hoot Owl by Sean Taylor Activity SheetDocumento5 páginasHoot Owl by Sean Taylor Activity SheetRandom House of Canada100% (1)

- Marilyn's Monster Story Hour KitDocumento4 páginasMarilyn's Monster Story Hour KitRandom House of CanadaAinda não há avaliações

- Emma by Alexander McCall SmithDocumento19 páginasEmma by Alexander McCall SmithRandom House of CanadaAinda não há avaliações

- The Soup Sisters and Broth Brothers Edited by Sharon HaptonDocumento12 páginasThe Soup Sisters and Broth Brothers Edited by Sharon HaptonRandom House of CanadaAinda não há avaliações

- Edie's Ensemble Coloring PageDocumento1 páginaEdie's Ensemble Coloring PageRandom House of CanadaAinda não há avaliações

- Edie's Ensembles Paper DollsDocumento2 páginasEdie's Ensembles Paper DollsRandom House of CanadaAinda não há avaliações

- The Rat by Elise Gravel Teacher's GuideDocumento7 páginasThe Rat by Elise Gravel Teacher's GuideRandom House of CanadaAinda não há avaliações

- The Judy Moody Reading LogDocumento2 páginasThe Judy Moody Reading LogRandom House of CanadaAinda não há avaliações

- The Slug by Elise Gravel Teacher's GuideDocumento8 páginasThe Slug by Elise Gravel Teacher's GuideRandom House of CanadaAinda não há avaliações

- Appetite Announces New Cookbook From Nigella LawsonDocumento2 páginasAppetite Announces New Cookbook From Nigella LawsonRandom House of CanadaAinda não há avaliações

- Margaret Atwood PosterDocumento1 páginaMargaret Atwood PosterRandom House of CanadaAinda não há avaliações

- The Fly by Elise Gravel Teacher's GuideDocumento9 páginasThe Fly by Elise Gravel Teacher's GuideRandom House of Canada100% (1)

- Plague by CC HumphreysDocumento16 páginasPlague by CC HumphreysRandom House of Canada100% (1)

- Panic in Pittsburgh Teacher GuideDocumento9 páginasPanic in Pittsburgh Teacher GuideRandom House of CanadaAinda não há avaliações

- Up Ghost River by Edmund MetatawabinDocumento18 páginasUp Ghost River by Edmund MetatawabinRandom House of Canada100% (1)

- Between Gods by Alison PickDocumento14 páginasBetween Gods by Alison PickRandom House of CanadaAinda não há avaliações

- A Spy Among Friends by Ben MacintyreDocumento13 páginasA Spy Among Friends by Ben MacintyreRandom House of Canada75% (4)

- The Book of Unknown Americans by Cristina HenriquezDocumento14 páginasThe Book of Unknown Americans by Cristina HenriquezRandom House of Canada19% (31)

- The Mystery of The Russian Ransom Teacher GuideDocumento11 páginasThe Mystery of The Russian Ransom Teacher GuideRandom House of CanadaAinda não há avaliações

- Reader's Guide: All The Broken Things by Kathryn KuitenbrouwerDocumento6 páginasReader's Guide: All The Broken Things by Kathryn KuitenbrouwerRandom House of CanadaAinda não há avaliações

- The Reluctant Journal of Henry K. Larsen GuideDocumento14 páginasThe Reluctant Journal of Henry K. Larsen GuideRandom House of Canada100% (1)

- Remains of The Day by Kazuo IshiguroDocumento19 páginasRemains of The Day by Kazuo IshiguroRandom House of Canada67% (21)

- Julia, Child Recipe CardDocumento3 páginasJulia, Child Recipe CardRandom House of CanadaAinda não há avaliações

- Delicious! by Ruth Reichl - Book Club Party KitDocumento6 páginasDelicious! by Ruth Reichl - Book Club Party KitRandom House of CanadaAinda não há avaliações

- The Table of Less Valued Knights by Marie PhillipsDocumento14 páginasThe Table of Less Valued Knights by Marie PhillipsRandom House of CanadaAinda não há avaliações

- Caesars: The Essential Guide To Your Favourite Cocktail by Clint Pattemore, Connie DeSousa, John JacksonDocumento15 páginasCaesars: The Essential Guide To Your Favourite Cocktail by Clint Pattemore, Connie DeSousa, John JacksonRandom House of Canada0% (1)

- J Robison 103 02 Note Taking GuideDocumento4 páginasJ Robison 103 02 Note Taking Guideapi-335814341Ainda não há avaliações

- Tracing A Red Thread PDFDocumento25 páginasTracing A Red Thread PDFIosifIonelAinda não há avaliações

- Origin and Brief History of The Church: I.God'S MessageDocumento4 páginasOrigin and Brief History of The Church: I.God'S MessageDanilyn Carpe Sulasula50% (2)

- Transistores PEAVEYDocumento25 páginasTransistores PEAVEYjefriAinda não há avaliações

- Me, Myself, and I - The New YorkerDocumento16 páginasMe, Myself, and I - The New YorkeredibuduAinda não há avaliações

- A Restaurant Dinning HallDocumento2 páginasA Restaurant Dinning HallEvanilson NevesAinda não há avaliações

- The World of Apu - RayDocumento21 páginasThe World of Apu - Rayjim kistenAinda não há avaliações

- ABELE Trad ALWYN The Violin and Its History 1905. IA PDFDocumento156 páginasABELE Trad ALWYN The Violin and Its History 1905. IA PDFAnonymous UivylSA8100% (2)

- College Fun and Gays: Anthology One by Erica Pike: Read Online and Download EbookDocumento7 páginasCollege Fun and Gays: Anthology One by Erica Pike: Read Online and Download EbookAsriGyu CullenziousAinda não há avaliações

- Banarasi Sari#Documento7 páginasBanarasi Sari#SHIKHA SINGHAinda não há avaliações

- Asinaria PDFDocumento176 páginasAsinaria PDFCésar Arroyo LAinda não há avaliações

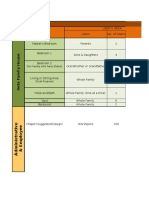

- Space Programming: Area/Space User'S Area Users No. of UsersDocumento6 páginasSpace Programming: Area/Space User'S Area Users No. of UsersMary Rose CabidesAinda não há avaliações

- Melissa May Robinson: Multimedia ArtistDocumento3 páginasMelissa May Robinson: Multimedia ArtistMd Gollzar HossainAinda não há avaliações

- 500 MilesDocumento4 páginas500 Milesshing6man6kwokAinda não há avaliações

- The Bane Chronicles: Vampires, Scones and Edmund Herondale ExtractDocumento14 páginasThe Bane Chronicles: Vampires, Scones and Edmund Herondale ExtractWalker Books60% (5)

- Rishikesh: "Yoga Capital of The World"Documento19 páginasRishikesh: "Yoga Capital of The World"Mahek PoladiaAinda não há avaliações

- Unit and Direct Support Maintenance Manual General Repair Procedures For ClothingDocumento443 páginasUnit and Direct Support Maintenance Manual General Repair Procedures For ClothingC.A. MonroeAinda não há avaliações

- Christie Agatha Eng 1201Documento33 páginasChristie Agatha Eng 1201Pfeliciaro FeliciaroAinda não há avaliações

- AFAR2 - Sales Agency, H.O., & Branch AccountingDocumento18 páginasAFAR2 - Sales Agency, H.O., & Branch AccountingVon Andrei MedinaAinda não há avaliações

- Films That Sell Moving Pictures and AdveDocumento169 páginasFilms That Sell Moving Pictures and AdveAlek StankovicAinda não há avaliações

- Musescore 3 Shortcuts: Other Score Elements Note EntryDocumento2 páginasMusescore 3 Shortcuts: Other Score Elements Note EntryLauRa Segura VerasteguiAinda não há avaliações

- Buddhism KhryssssDocumento2 páginasBuddhism KhryssssRhea MaeAinda não há avaliações

- Lesson 3.1 Jesus, The Epitome of A Prophet's Fate MartyrdomDocumento5 páginasLesson 3.1 Jesus, The Epitome of A Prophet's Fate MartyrdomBianca MistalAinda não há avaliações

- Landsat Manual 1 - Revised2019Documento6 páginasLandsat Manual 1 - Revised2019ខេល ខេមរិន្ទAinda não há avaliações

- Creative Nonfiction Q1 Week1 Day3Documento2 páginasCreative Nonfiction Q1 Week1 Day3Mary Jane Sebial ManceraAinda não há avaliações

- String QuartetDocumento2 páginasString QuartetChad GardinerAinda não há avaliações

- Meg Has To Move! - ExercisesDocumento2 páginasMeg Has To Move! - ExercisesGisele FioroteAinda não há avaliações

- OMAS Limited Editions 2009-2010Documento53 páginasOMAS Limited Editions 2009-2010MarcM77Ainda não há avaliações

- Coffin Texts Vol 8Documento0 páginaCoffin Texts Vol 8shasvinaAinda não há avaliações

- LetrasDocumento37 páginasLetrasOnielvis BritoAinda não há avaliações