Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

Encyclopedia of Global Environmental Change Vol 5

Enviado por

Artur De AssisDireitos autorais

Formatos disponíveis

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Encyclopedia of Global Environmental Change Vol 5

Enviado por

Artur De AssisDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Encyclopedia of

Global Environmental Change

e g e c

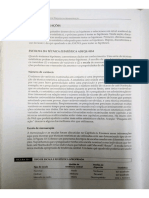

The volumes in this Encyclopedia are:

Volume One

The Earth system: physical and chemical dimensions of global environmental change

Volume Two

The Earth system: biological and ecological dimensions of global environmental change

Volume Three

Causes and consequences of global environmental change

Volume Four

Responding to global environmental change

Volume Five

Social and economic dimensions of global environmental change

Encyclopedia of

Global Environmental Change

e g e c

Editor-in-Chief

Ted Munn

Institute for Environmental Sciences, University of Toronto, Canada

5

Social and economic dimensions of global environmental change

Volume Editor

Peter Timmerman

IFIAS, Toronto, Canada

Copyright 2002 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, Chichester

Bafns Lane, Chichester

West Sussex PO19 1UD, UK

National: 01243 779777

International: ( 44) 1243 779777

e-mail (for orders and customer service enquiries): cs-books@wiley.co.uk

Visit our Home Page on http://www.wiley.co.uk

or http://www.wiley.com

Copyright Acknowledgments

A number of articles in the Encyclopedia of Global Environmental Change have been written by government employees in the United Kingdom, Canada

and the United States of America. Please contact the publisher for information on the copyright status of such works, if required. In general, Crown

copyright material has been reproduced with the permission of the Controller of Her Majestys Stationery Ofce. Works written by US government

employees and classied as US Government Works are in the public domain in the United States of America.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic,

mechanical, photocopying, recording, scanning or otherwise, except under the terms of the Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or under the terms

of a license issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency, 90 Tottenham Court Road, London, W1P 0LP, UK, without the prior permission in writing of

the publisher.

Other Wiley Editorial Ofces

John Wiley & Sons Inc., 605 Third Avenue,

New York, NY 10158-0012, USA

Wiley-VCH Verlag GmbH, Pappelallee 3,

D-69469 Weinheim, Germany

Jacaranda Wiley Ltd, 33 Park Road, Milton,

Queensland 4064, Australia

John Wiley & Sons (Asia) Pte Ltd, 2 Clementi Loop #02-01,

Jin Xing Distripark, Singapore 129809

John Wiley & Sons (Canada) Ltd, 22 Worcester Road,

Rexdale, Ontario M9W 1L1, Canada

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN: 0 471 97796 9

Typeset in 10pt Times by Laser Words Private Limited, Chennai, India

Printed and bound in Great Britain by Antony Rowe, Chippenham, Wiltshire

Editorial Board

Editor-in-Chief

Ted Munn

Institute for Environmental Studies, University of Toronto, Canada

Volume Editors

Volume One The Earth system: physical and chemical dimensions of global environmental change

Dr Michael C MacCracken, Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory, California, USA and

Dr John S Perry, formerly, National Research Council USA

Volume Two The Earth system: biological and ecological dimensions of global environmental change

Professor Harold A Mooney, Stanford University, Stanford, USA and

Dr Josep G Canadell, GCTE/IGBP, CSIRO Sustainable Ecosystems, Canberra, Australia

Volume Three Causes and consequences of global environmental change

Professor Ian Douglas, University of Manchester, Manchester, UK

Volume Four Responding to global environmental change

Dr Mostafa K Tolba, International Center for Environment and Development, Cairo, Egypt

Volume Five Social and economic dimensions of global environmental change

Mr Peter Timmerman, IFIAS, Toronto, Canada

International Advisory Board

Dr Joe T Baker

Commissioner for the Environment, ACT, Australia

Professor Francesco di Castri

CNRS, France

Professor Paul Crutzen

Max Planck Institute for Chemistry, Germany

Professor Eckart Ehlers

IHDP/IGU Germany

Professor Jos e Goldemberg

Universida de S ao Paulo, Brazil

Dr Robert Goodland

World Bank, USA

Professor Hartmut Grassl

WCRP, Switzerland

Professor Ronald Hill

University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong

Dr Yu A Izrael

Institute of Global Climate & Technology, Russia

Professor Roger E Kasperson

Clark University, USA

Professor Peter Liss

University of East Anglia, UK

Professor Jane Lubchenco

Oregon State University, USA

Mr Jeffrey A McNeely

IUCN, Switzerland

Professor Thomas R Odhiambo

Hon. President, African Academy of Sciences and

Managing Trustee, RANDFORUM, Kenya

Sir Ghillean T Prance

University of Reading, UK

Professor Steve Rayner

Columbia University, USA

Contents

Preface to the Encyclopedia of Global Environmental Change ix

Preface to Volume Five xv

The Human Dimensions of Global Change 1

The Changing Human Nature Relationships (HNR) in

the Context of Global Environmental Change 11

Economics and Global Environmental Change 25

Ecological Economics 37

Environmental Politics 49

Global Environmental Change and Environmental

Histor y 62

Globalization in Histor ical Per spective 73

Technological Society and its Relation to Global

Environmental Change 86

Relating to Nature: Spir ituality, Philosophy, and

Environmental Concer n 97

Social Science and Global Environmental Change 109

The Emer gence of Global Environment Change into

Politics 124

The Environment and Violent Conict 137

Development and Global Environmental Change 150

Anthropology and Global Environmental Change 163

Art and the Environment 167

Attenborough, David 175

Bahai Faith and the Environment 176

BAT (Best Available Technology) 183

Bateson, Gregory 183

Brent Spar 184

Brower, David 185

Buddhism and Ecology 185

Business-as-usual Scenarios 191

Carson, Rachel Louise 192

CBA (Cost Benet Analysis) 193

Chipko Movement 193

Christianity and the Environment 194

Circulating Freshwater: Crucial Link between Climate,

Land, Ecosystems, and Humanity 201

Commons, Tragedy of the 208

Cousteau, Jacques 209

Deep Ecology 211

Demographic transition 211

Discounting 214

Earth Charter 216

Earth Day 216

Earth First! 217

Ecocentric, Biocentric, Gaiacentric 217

Ecofeminism 218

Eco-socialism 224

Ecosystem Approach 225

Ecosystem Services 226

Emergy 228

Encyclopedias: Compendia of Global Knowledge 228

Enlightenment Project 229

Environmental Defense Fund 230

Environmental Economics 230

Environmental Ethics 231

Environmental Movement the Rise of Non-government

Organizations (NGOs) 243

Environmental Philosophy: Phenomenological

Ecology 253

Environmental Psychology/Perception 257

Environmental Security 269

Environmental Sociology 278

Equity 279

Exxon Valdez Oil Spill 283

Francis of Assisi 284

Friends of the Earth 285

Futures Research 285

Gaia Hypothesis 287

Gandhi, Mohandas Karamchand 290

Governance and International Management 292

Hazards in Global Environmental Change 297

Hinduism and the Environment 303

Homocentric 311

Human Body, Immediate Environment 312

Indigenous Knowledge, Peoples and Sustainable

Practice 314

International Environmental Law 324

ISEW (Index of Sustainable Economic Welfare) and GPI

(Genuine Progress Indicator) 331

viii CONTENTS

Islam and the Environment 332

ISSC (International Social Science Council) 339

Jains and the Environment 341

Judaism and the Environment 349

Kelly, Petra 355

Kondratyev, Nikolai Dmitrievich 356

Landscape, Urban Landscape, and the Human Shaping of

the Environment 357

Leopold, Aldo 367

Life Style, Private Choice, and Environmental

Governance 368

Literature and the Environment 370

Love Canal 382

Malthus, Thomas Robert 384

Man and Nature as a Single but Complex System 384

Modeling Human Dimensions of Global Environmental

Change 394

Modernity vs. Post-modern Environmentalism 408

Muir, John 411

Nasr, Seyyed Hossein 412

National Environmental Law 413

Nature 419

New Ageism 420

NIMBY (Not In My Backyard) 421

Noosphere 421

Phase Shifts or Flip-ops in Complex Systems 422

Political Movements/Ideologies and the

Environment 429

Political Systems and the Environment:

Utopianism 443

Post-normal Science 451

Precautionary Principle 455

Property Rights and Regimes 457

Religion and Ecology in the Abrahamic Faiths 461

Religion and Environment Among North American First

Nations 466

Roosevelt, Theodore 475

Scenarios 476

Seveso 482

Sierra Club 483

Small is Beautiful 483

Social Ecology 484

Social Impact Assessment (SIA) 484

Social Learning in the Management of Global

Atmospheric Risks 485

Soft Energy Paths 487

Sovereignty and Sovereign States 487

Sustainability: Human, Social, Economic and

Environmental 489

Theology 492

Theories of Health and Environment 492

Thoreau, Henry David 502

Three Mile Island 503

Torrey Canyon 503

UNU (United Nations University) 504

Virtual Environments 505

Waldsterben 508

WCC (World Council of Churches) 509

Alphabetical List of Articles 511

List of Contributors 523

Selected Abbreviations and Acronyms 553

Index 569

Preface to the Encyclopedia of Global

Environmental Change

THE ENVIRONMENT

The word environment, whose dictionary meaning is simply

that which surrounds, has in the last few decades become

a buzzword , encompassing an exceedingly diverse array

of elements and social issues. Taking the original meaning

as a point of departure, it is clear that we humans depend

totally on the environment provided by planet Earth for

the food we eat, the water we drink, and the air we

breathe. Thus changes in this environment must be of

vital concern. Will Earth continue to sustain humans in

a way that also encourages the ourishing of the other

living things with whom we share the planet? This question

has loomed ever larger as it has become more evident

that human activities have been inducing major changes

in all of the compartments of the global environment. We

have converted forests and savannas to farms and cities;

we have exhumed ancient treasures of fuels and minerals;

we have used the rivers and winds as convenient sewers;

and we have released entirely new chemical compounds

and organisms into the environment. In the 1960s, the

scienti c community began to use the word environment

in this new non-specialist sense. Soon too, Departments

of the Environment were created by many governments,

and new scienti c journals began publication while others

were re-named. For example, the International Journal of

Air Pollution became Atmospheric Environment ! In the

ensuing decades, the world community has come to see

the environment in many different ways, as a life-support

system, as a fragile sphere hanging in space, as a problem,

a threat and a home.

GLOBAL ENVIRONMENTAL CHANGE

A broader and deeper understanding of the global aspects of

environmental concerns emerged in the 1970s and 1980s,

and a new phrase global environmental change acquired

popular currency. Paleoresearch had revealed that environ-

mental change was far from new, and by no means the

sole result of the actions of heedless humans. Since the

planet s formation, virtually every element of its environ-

ment has been undergoing massive changes on all space and

time scales. Oxygen waxed and carbon dioxide waned in

the atmosphere. Continents moved about the planet s sur-

face like scum on a soup kettle. Great ice sheets grew and

shrank. Above all, the force of life (the biosphere) emerged

as a dominant driver of planetary change.

However, another vital insight began to emerge about

1980: the inescapably interlinked nature of these many

environmental changes. On the very longest time scales,

continental drift moved lands into different climates but

also changed the climate of the globe itself. Photosyn-

thetic life changed the atmosphere but also made possible

more advanced life forms that could take advantage of the

new environment. On shorter time scales, atmosphere and

ocean often interact to produce the massive changes in

the Southern Paci c that we term El Ni no and La Ni na,

whose consequences extend across the planet, and pro-

foundly affect even our socioeconomic systems. Indeed,

we have come to realize that human-induced perturbations

in the environment are becoming increasingly large, and

are potentially coming to dominate the natural workings of

the complex and interdependent global system that sustains

life on Earth. Humans and their global environment are no

longer independent; they are ever-increasingly becoming

interdependent components of a single global system.

Thus, the term global environmental change has come to

encompass a full range of globally signi cant issues relat-

ing to both natural and human-induced changes in Earth s

environment, as well as their socioeconomic drivers. This

implicitly includes concerns for the capacity of the Earth to

sustain life that have motivated the development of stud-

ies of global change and sustainable development in the

last few decades. Analyses of global environmental change

therefore demand input from the social sciences as well as

the natural sciences (and indeed also from the engineering

and health sciences) necessitating an inescapably inter-

disciplinary approach.

Scientists from many disciplines have been attracted

to this growing eld of global environmental change.

This is particularly noticeable in the biological sciences

through the encouragement of IGBP (International Geo-

sphere Biosphere Programme), which invites ecologists to

expand their eld of vision from the plot and landscape

scales to the regional, continental and global ones, and to

interact with scientists from other disciplines in exploring

environmental change at these larger scales. Indeed this

trend has encouraged publishers and scienti c societies to

introduce new journal titles, and these publications from all

accounts appear to be ourishing.

At the same time, human social, economic, and cultural

systems are rapidly changing under the in uence of growing

globalization. In the economic sphere, for example, today s

discourse centers on multinational corporations, the Global

x PREFACE TO THE ENCYCLOPEDIA OF GLOBAL ENVIRONMENTAL CHANGE

Economy, and the Globalization of Trade. Thus, the

agendas of most of the physical, life, and social sciences

increasingly focus on global-scale changes.

THE EVER-CHANGING ENVIRONMENT

Since the launching of Earth-viewing satellites, we have

been able to see a constantly updated moving picture of

our planet. Great weather systems sweep around the globe,

waves of green and brown ebb and ow over the continents

with the seasons, as do white waves of ice and snow.

Nevertheless, a remarkable feature of the Earth system

has been its relative stability. Since the dawn of life,

the planets environment has remained within a range of

conditions that has supported life. Moreover, with some

notable and perhaps cautionary exceptions, changes from

year to year, decade to decade, millennium to millennium,

have been modest, particularly during the last 10 000 years.

Many features of human society exhibit similar behavior.

Civilizations and cultures evolve slowly for the most part

in response to environmental, economic, and social driving

forces over their long lives. Great cities like Rome endure

through the ages. A citizen of ancient Babylon probably

would have little difculty understanding the politics of

modern Toronto.

But today we appear to be entering an era of change

unprecedented since Babylon was a cluster of mud huts.

There are many reasons to believe that changes greater than

humankind has experienced in its history are in progress

and are likely to accelerate.

Virtually every measure of human society numbers of

people and automobiles, airplanes, energy consumption,

generation of waste is increasing exponentially. While the

values of a few indicators are leveling off, the magnitudes

of annual increases of others remain immense.

Major changes are becoming evident in many critical ele-

ments of the environment increasing carbon dioxide con-

centrations, stratospheric ozone depletion (not to mention

the stratospheric Antarctic ozone hole and the possibility of

a similar Arctic event), rising sea level, declining produc-

tivity of soils, widespread collapses of sheries, dramatic

declines in biodiversity, destruction of tropical forests, etc.

Within living memory, the countryside around large cities

has been swallowed up by suburban developments and

highways. Humans are stepping on the gas pedal of the

planets environment, and perhaps recklessly breaking the

survivable speed limit of global change.

Paleoclimatological studies have shown that the sta-

ble environment that we take for granted has not always

prevailed. Indeed, the relatively brief period in which

human civilization has developed is somewhat unusual in

its equable stability. Neolithic hunters in Europe some

13 000 years ago saw their climate shift from temperate to

glacial in a single short lifetime. The evolution of human

society is punctuated by wars, pestilence, and technological

revolutions. Major perhaps even catastrophic change

could occur in the future, because we know it has occurred

in the past.

Rapidly advancing understanding of both natural and

human systems and above all the ability to translate that

understanding into quantitative models has enabled us to

explore the future of our global society and its global cli-

mate with unprecedented realism. Although prediction of

the single future path that we will follow is inherently

unpredictable, it is possible to map a broad range of future

environmental trajectories that we might take, each com-

pletely consistent with our understanding of how the system

works. Such scenario-building exercises amply conrm our

concerns that the changes of the 21st Century could be

far greater than experienced in the last several millennia.

Business-as-usual for human society appears to imply

business-as-highly-unusual for the global environment.

THE INTERLOCKING

BIOGEOPHYSICAL SOCIOECONOMIC

SYSTEMS

Recognition came in the 1970s that many of the environ-

mental issues are inter-connected through the biogeochem-

ical cycling of trace substances, especially carbon, sulfur,

nitrogen and phosphorus. In fact, in a prescient statement

on the main environmental research priority of the 1980s,

Mostafa Tolba (then Executive Director of the United

Nations Environment Programme) and Gilbert White (then

President of the Scientic Committee on Problems of the

Environment) drew the attention of both the scientic and

the science-policy communities to the need to understand

the major global biogeochemical cycles in order to main-

tain the global life support systems in a healthy state (Tolba

and White, 1979). Quoting from that statement,

We draw attention to the fundamental scientic importance of

understanding the biogeochemical cycles which link and unify

the major chemical and biological processes of the Earths sur-

face and atmosphere. The results will have practical signicance

for all of us who inhabit an Earth with limited resources and

who, by our actions, increasingly affect the quality of the human

environment.

So it is that many of the global environmental issues acid

rain, stratospheric ozone depletion, climate change, nitro-

gen over-fertilization are inter-related through the global

biogeochemical cycles.

One of the interesting results of the study of the Earths

history has been the discovery of the global teleconnec-

tions of the Earth system, with some major climatic shifts

occurring simultaneously in the two hemispheres. In an

analogous way, there has been recognition for a long time

that human social, economic, and cultural systems are glob-

ally inter-related. That these are connected in turn to the

PREFACE TO THE ENCYCLOPEDIA OF GLOBAL ENVIRONMENTAL CHANGE xi

Earth system was implicitly recognized as early as the 1972

Stockholm Conference on the Human Environment.

To manage the human responses to this enormously var-

ied but at least moderately coupled world system in an

era of increasing global change through the diverse array

of local, national and international organizations is indeed a

daunting challenge. An essential rst step is to describe past

and present states, then to explain the various phenomena

observed, and nally to develop predictive models (or at

least a range of scenarios) describing the future behavior of

this total SocioeconomicCultural Environmental system.

In this process, environmental scientists must learn how

to assimilate better the new information constantly being

received, although uncertainties, often large, will continue

to exist. Within this mix, rational and effective policies must

be developed that will balance the risks and costs of global

environmental change in an adaptive way. Only then will

we be able to even formulate, much less start to implement,

rational and effective policies that cope effectively with

global change. The prospect of change tempts us to think

in terms of winners and losers. However, such analyses

often do not play out in simple ways. For example, a mod-

est increase in rainfall would cause farmers to rejoice while

vacationers would despair. However, greater farm produc-

tion can lead to lower commodity prices, thereby reducing

farm incomes while making vacation food purchases less

expensive. Human society is pretty well adapted to the

present environment, so change is necessarily a challenge.

In the longer-term, much depends on the ability of soci-

eties to respond, to adapt. Societies will differ in the

resources natural, human, and technological that are

available to them. They will also differ in terms of the

values and priorities they attach to physical, social, and

environmental goals, and in the social and political mech-

anisms that they employ to seek these goals. These dif-

ferences in the human world of generations yet unborn

may be as great and as signicant as the changes in

the global environment. A major challenge for our times is

to develop frameworks for understanding complex interdis-

ciplinary issues of this complexity.

No discussion of change and the future can be complete

without consideration of risk. Projections of the future,

however imaginative or soundly based, necessarily cen-

ter on plausible, surprise-free scenarios population will

increase, economies will advance, climate will change all

typically slowly and smoothly. However, such projections

made at the beginning of the 20th Century would have

missed two World Wars, the automobile, aviation, space

travel, television, and McDonalds in Beijing. By deni-

tion, genuine surprises cannot be predicted. However, an

understanding of the impacts of past surprises may help us

to make our society and our world somewhat more robust

in the face of the unknown surprises that await us.

THE HUMAN DIMENSIONS OF GLOBAL

ENVIRONMENTAL CHANGE

The human dimension of global change has been dened

as the ways in which individuals and societies contribute

to global environmental change, are inuenced by it, and

adapt to it. Many empirical studies have been undertaken

that describe human activities in physical terms, based on

various kinds of indicators. Rates of deforestation, urban-

ization, and changing levels of emissions of greenhouse

gases are only some measurable contributors to environ-

mental change. But the dynamics of human activities and

global change are much more complex, and they reect the

complexities of the humannature relationship.

While the sheer burden of human activity on the planet

is important, we know that the major forces at work are

human beings operating together through political systems,

corporations, interest groups, and beliefs that sway whole

peoples. These raise questions about the nature of choice,

about the hopes, dreams, and frustrations that impel people

forward, or block them. At the moment, for instance, the

dream of the good life which has been a critical element

of every religious tradition in the world is increasingly

being dened in terms of material possessions and powerful

images that are shown on global media. Can this particular

version of human happiness be sustained on a limited

planet? Some people say that it can; others say that it

cannot.

The central questions about the role of human beings

in global environmental change revolve around social, cul-

tural, economic, ethical, and even religious issues. These

are becoming more and more pressing, and more and more

foundational as human beings deliberately or inadvertently

modify more and more of the planet. It is also obvi-

ous that in this generation the modication of organisms

and ecosystems may well extend to the modication of

human beings themselves. Among the fundamental ques-

tions are: What motivates us towards saving or harming

the environment? How do we see ourselves with regard to

nature? What is our responsibility to this and future gen-

erations? Who do we think we are, and who would we

like to become? Appropriately enough, Volume Five of this

Encyclopedia wrestles, in many different voices, with these

ultimate questions that remain intimately linked with the

sweep of physical, chemical, biological, geographical, and

institutional changes documented and discussed throughout

the earlier four volumes.

The Brundtland philosophy urges us not to reduce options

for future generations. Implementation of this idea is, how-

ever, difcult. For example, it often seems more compelling

to alleviate current poverty than to protect the environment

and renewable resources for future generations. Many sci-

entists agree that new approaches are needed to meld the

social with the natural sciences in the policy arena. Some of

the new methodologies that go beyond the physical sciences

xii PREFACE TO THE ENCYCLOPEDIA OF GLOBAL ENVIRONMENTAL CHANGE

are described in Volumes Four and Five of this Encyclo-

pedia, e.g., post-normal science, integrated environmental

assessment, and the precautionary principle.

In a commentary in which he described the 21st Cen-

tury as the century of the environment, Edward O. Wilson

began by referring to the growing consilience (the inter-

locking of causal explanations across disciplines) so that the

interfaces between disciplines become as important as the

disciplines themselves. He then stated that this interlock-

ing amongst the natural sciences will in the 21st Century

also touch the borders of the social sciences and humani-

ties. In the environmental context, environmental scientists

in diverse specialities, including human ecology, are more

precisely dening the arena in which that species arose,

and those parts that must be sustained for human survival

(Wilson, 1998).

This is a major challenge for environmental scientists.

Already through DNA techniques, for example, it is possi-

ble to trace back connections amongst prehistoric peoples

through the last Ice Age to modern times.

THIS ENCYCLOPEDIA OF GLOBAL

ENVIRONMENTAL CHANGE

More than two million papers are published every year in

science and medicine, a twentyfold increase since 1940 that

taxes the resources of concerned citizens, scientists, uni-

versity departments, research institutes and libraries. At the

same time, many policy-motivated organizations nd it dif-

cult to draw together the necessary expertise for resolving

the newly emerging environmental issues. The scientic

literature relating to the environment is burgeoning. How-

ever, research syntheses are in general still scattered across

a broad spectrum of journals and books, and information

on global environmental change is not readily available in

an inter-related way. In particular, it is quite uncommon

for contributions from the natural sciences to appear in

the same journal or workshop proceedings as contributions

from the social sciences and the humanities.

This Encyclopedia of Global Environmental Change is

a comprehensive and integrated reference in the broad

area of global environmental change that will be con-

veniently accessible and productively usable by students,

managers, administrators, legislators, and concerned citi-

zens. The Encyclopedia consists of ve volumes of inter-

related material:

Volume 1 The Earth system: physical and chemical

dimensions of global environmental change

(Michael C MacCracken and John S Perry,

editors)

Volume 2 The Earth system: biological and ecological

dimensions of global environmental change

(Harold A Mooney and Josep G Canadell,

editors)

Volume 3 Causes and consequences of global environ-

mental change (Ian Douglas, editor)

Volume 4 Responding to global environmental change

(Mostafa K Tolba, editor)

Volume 5 Social and economic dimensions of global env-

ironmental change (Peter Timmerman, editor)

The rst four volumes cover the broad issues of the sci-

ence and politics of global environmental change. Volume

Five adds an often understated but extremely important

aspect, linking as it does, global environmental change

to the socioeconomic, cultural and ethical dimensions of

human societies. Here will be found a rich panoply of writ-

ings by people who are not natural scientists but who have

thought deeply about the environment. It places global envi-

ronmental change in a refreshing historical, sociological and

cultural context. In many contributions, the time horizons

of most interest are the last hundred and the next hundred

years. However, some contributions dip backward millions

of years. Throughout, the emphasis is upon the dynam-

ics of the various processes discussed how and why did

they change? A second recurrent theme is the interconnec-

tion of processes and changes What produces change?

What is impacted by change? Finally, we attempt to deal

even-handedly with natural and human-induced change, and

with impacts on both the natural world and human society.

From the numerous diverse articles in the Encyclopedia,

we believe that the user can obtain a coherent picture of

this complex and dynamic system of which we all are

a part.

To assist in promoting this coherence, each volume

begins with a group of extended essays on major top-

ics that embrace the eld covered in that volume. These

are intended to provide an introduction to the topic, a

convenient road map through cross-references for explor-

ing the Encyclopedia. Then there follows, in alphabetical

order, shorter articles on a variety of scientic topics,

descriptions of scientic programs, denitions, acronyms,

and biographies of leading contributors to the eld from

Charles Darwin, through the Russian ecologist Vernad-

ski, to the three most recent environmental Nobel Laure-

ates Crutzen, Rowland and Molina. Indeed, these deni-

tions, biographies and acronym denitions are, we believe,

a uniquely valuable feature of the Encyclopedia. In the case

of acronyms of international organizations and programs, it

is no exaggeration to state that a young environmental sci-

entist requires not only a good understanding of science,

but also a good knowledge of acronyms, if they are to

follow the discussions taking place at many international

meetings! Also included in the alphabetic listings are abun-

dant cross-references to related topics in the same or other

volumes.

The substantive scientic articles that comprise the

meat of the Encyclopedia are original contributions

by active scientists from around the world, and thus

PREFACE TO THE ENCYCLOPEDIA OF GLOBAL ENVIRONMENTAL CHANGE xiii

represent authoritative and up-to-date summaries of the

state of current knowledge, direct from the producers of

this knowledge. A number of these articles break new

ground in synthesizing and summarizing our understanding

from novel viewpoints and in unconventional ways. Thus,

readers will nd a wide variety of styles and approaches

within the articles, reecting in a unique way the rich

diversity of todays world science. The articles have also

had the benet of careful reviews, particularly by our Edi-

tors.

The scientic essays and some of the program descrip-

tions begin with a few italicized paragraphs written for

non-specialists. These are not intended to be abstracts of

the paper to follow, but rather are aimed at providing the

reader with an introduction into why the topic is impor-

tant and where it ts into the broader aspects of global

change a kind of encouragement to read on. Reading

on should not be too difcult a task, since most of the

scientic essays are written at the level of journals such

as Scienti c American and AMBIO that are intended for

the non-specialist. The Encyclopedia will be a valuable

source of information for everyone with a general interest

or a need-to-know in the various environmental elds (the

natural sciences, socio-economics, engineering, the health

sciences, and policy analyses) particularly as they relate to

global-scale environmental change, its drivers, and its con-

sequences. It is also expected that among the audiences for

each volume will be practitioners and researchers in the

elds covered by the other four volumes. We believe that

this rather unusual indeed unique Encyclopedia will be

used in a variety of ways.

1. Some people will employ it simply as a convenient

source of information on specic topics What has been

happening recently to the sea ice in the Arctic Ocean?

Who was Roger Revelle? What is soil mineralization?

What is ICSU or IGBP? What is the Kyoto Protocol?

What is deep ecology?

2. Serious students in the environmental sciences may

begin by reading one or all of the introductory essays,

which present highly compressed crash courses in a

range of central topics.

3. We believe that the substantive specialized articles that

constitute the bodies of the volumes are productively

and enjoyably readable in their own right.

4. Finally, a case has been made by one of the volume edi-

tors (Peter Timmerman) for encyclopedia browsing as

an enjoyable and productive pastime (see Encyclope-

dias: Compendia of Global Knowledge, Volume 5).

We believe that these ve volumes are in the tradition of the

human aspiration towards the compilation of global knowl-

edge that sparked the preparation of the rst encyclopedias

in the 18th Century.

Our Editors have had the benet of a marvellous post-

graduate education in the course of the Encyclopedias

evolution! We are immensely grateful to the many, many

authors in our virtual university who have contributed

their wisdom to this project.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

Many helpful comments and draft paragraphs were received

from the Volume Editors during the preparation of this

Preface.

REFERENCES

Tolba, M K and White, Gilbert F (1979) Global Life Support

Systems, SCOPE Newsletter, No. 7, October. 2 pp.

Wilson, Edward O (1998) Integrated science and the coming

century of the environment, SCIENCE 279, 20482049.

Ted Munn

Editor-in-Chief

Preface to Volume Five

Volume Five is devoted to the social, political, economic,

and spiritual dimensions of global environmental change,

and as such represents a departure from the conventional

focus on the purely physical aspects of global change.

It highlights the profound shifts in human thinking and

awareness that are required to wrap our minds around the

advent of globalization, and our increasing ability to affect

natural systems, sometimes to our own benet, sometimes

not. This powerful role cannot simply be captured by

treating human beings as if they were another natural

force. Social, cultural, and economic ideas and institutions

shape the desires and hopes, the conicts and resolutions

of conict that are central to the human dimension of

global change. Yet, at the same time, human beings are

incontestably part of nature as other volumes in this

Encyclopedia demonstrate. Volume Five overlaps with, and

complements, these other volumes.

Because of the complex weave of interaction between

humanity and the environment, this volume contains many

essays and articles that are more in the realm of probes

than xed descriptions of their topics. Powerful words and

powerful ideas, metaphors, myths, beliefs, images and arte-

facts these are all vehicles for the creation and shaping

of meaning among human beings. Topics covered include

the great political and economic theories, the most inuen-

tial views of nature from Plato to Rachel Carson, and the

historic and literary seedbeds for the rise of environmental

thought and practice in our time.

Of particular importance in this volume are the introduc-

tory essays from leading gures in the eld, and special

efforts have been made throughout to give space to alterna-

tive voices and ideas. Dialogue and diversity are essential to

human development, and we hope that the reader is stim-

ulated by this volume towards his or her own thoughtful

response to the increasing responsibility for the future of

the Earth that has come upon us in our time.

Among the voices that we are privileged to present in

this volume, the Editors would like to single out that of

Ester Boserup, whose pathbreaking work as a student of

the social dynamics of technological change, and of the

role of women in economic development, make her an

exemplar of the kind of interdisciplinary thinker so often

proclaimed as necessary, and so seldom found. She died

before the Encyclopedia could go to press, but we would

like to dedicate this volume to her memory.

Peter Timmerman

Editor of Volume Five

The Human Dimensions of Global Change

PETER TIMMERMAN

University of Toronto, Toronto, Canada

The central icon of the environmental movement is the earth hanging in space, that mysterious and unexpected

cargo brought back from the voyages to the moon. See Figure 1 in The Earth System, Volume 1. It appears

on bedroom walls, refrigerators, and annual reports by multinational food companies. Blue-green and spherical

against the stark blackness of space, it speaks of all things natural, all things green, the vision of one earth,

one world.

Yet, part of its paradox is that this environmental symbol

was the result of the most advanced technological project

in human history (at that time), whose roots are easily

traceable to the challenge of the Cold War, the long-range

missile projects beginning in World War II, the atomic

bomb, the militarization of space, and even the elegant

camera technology that enabled the pictures to be taken.

But the image is even more iconic and mysterious than

that. At rst glance, it appears a lonely image the only

home we have devoid of human reference points, at least

at the distance of the moon. Yet a nagging question is:

where are we in this picture? The easy answer is that we

are in there somewhere, maybe waving, or drowning. The

more intriguing answer is that we are the picture: that it took

all of science and technology that is, all of the ability to

provide a temporary earth in a plastic suit in deep space

to keep a human alive and all of history, that is, not just

evolution, but all the social and cultural reasons that would

make a being turn around at a precise moment oating in

space, pick out the earth from the surrounding darkness

as something worth photographing, and then lift a camera

to his eyes, focus, and take a picture with some purpose

in mind.

The literary critic, Marshall McLuhan, made a typically

prophetic remark in 1970, in an obscure inaugural piece in

an early environmental magazine (since defunct):

whereas the planet had been the ground for the human popula-

tion as gure; since Sputnik, the planet has become gure and

the satellite surround has become the new ground . Once

it is contained within a human environment, Nature yields its

primacy to art.

McLuhan here invokes the familiar image of the gure-

ground reversal the faces that turn into vases, and back

again; or the duck that ips into a rabbit and ducks back

again to suggest that while up until the arrival of the

image from space, human beings saw themselves as gures

on a ground, the environment is now a mere gure on

human grounds.

The gure-ground reversal suggests that this is a sudden

perceptual shift; which may be the case, but its elements

have been arriving for some time.

One early element can be found in the idea that the

higher you go off the earth, the closer you approach the

realm of God. This is obviously exhilarating, but it is

also blasphemous and unsettling. An early source is the

temptation of Jesus, who, after being baptized by John,

goes into the wilderness where he is threatened by the devil.

Among the trials he undergoes is that of the potential for

total earthly power; and the devil takes him to the highest

point of the world and shows it all to him before Jesus

rejects it. Peaks are for falling off of, as well as for gaining

perspective.

In later medieval literature, airborne journeys of a more

lighthearted sort take to the skies, the hero drawn by geese

or lifted up by air currents, or in a dream. Yet when Dante

leaps off the earth and moves into the higher realms in The

Divine Comedy, it is clear that this is unsettling. A later

appearance of the earth from space, in Milton s Paradise

Lost is ominously seen from the perspective of Satan, newly

released from the prison of Hell, and ying around the

universe looking for a new home away from home.

This Godlike stance, epitomized by the image of the earth

from space, is, as literature suggests, powerful. The arrival

of global maps and globes in the 16th century was part of

the great surge of Western power that began with the age

of discovery and has only intensi ed its reach in the age

of the Internet. The ability to hold the world in our minds

is the forerunner of the ability to hold it in our hands, and

vice versa.

2 SOCIAL AND ECONOMIC DIMENSIONS OF GLOBAL ENVIRONMENTAL CHANGE

Today we continue the same process. Again, it was

McLuhan who said that in the age of satellites there is

no more wilderness. There is hardly anywhere on the earth

where one can hide, for example, from cruise missiles that,

guided by satellite, can drop on a designated square meter

of ground. The Hubble telescope, of which we have heard

so much, has sister scopes whose magnifying powers are

turned in to gaze on the details of our lives. It is clear

that the American Armed Forces believe that the next high

ground for military superiority is the satellite surround.

Evidence of this could be found during the Gulf War in

1991, when the rst action of the Allied powers was to cut

off access to international satellite pictures for the Iraqis,

the result being that they were forced to ght essentially

blind.

Another related element, contributing to the gure-

ground reversal, is the gradual increase in humankinds

inuence over the physical systems of the planet. Other

volumes in this encyclopedia highlight this encroachment,

where human beings are creaming off and rearranging vast

parts of the earths primary production for our own pur-

poses. Certainly human beings have affected large chunks

of the earths natural terrain before, but the ability to affect

whole physical and chemical cycles of the planet surely

represents a watershed (airshed, earthshed) in earths his-

tory. Our ngers and ngerprints are now and will continue

to be all over the genetic future of a myriad species. The

ground plans in which they will gure are human inu-

enced, human inspired.

THE HUMAN DIMENSION OF GLOBAL

CHANGE

A volume of an encyclopedia on global environmental

change that deals with the human dimension of global

change is thus necessarily confronted with fundamental

issues, of which the most fundamental remains: what does

it mean to be human?

Tightly related questions, but more obviously tractable

(though one need not get too carried away with tractability)

are: what is the relationship between human meanings and

goals, and the tools, such as science and technology, that

we are using to make those meanings and meet those

goals? What does the humanizing of the planet mean? Is it

manageable, possible, agreeable, delightful, horrifying?

In 1996, the philosopher Thomas Nagel published a

book called The View From Nowhere (Nagel, 1996), which

describes in detail the stance which modern science wishes

to take. Another philosopher, Hilary Putnam, actually refers

to this stance as Gods Eye View (Putnam, 1995). The ear-

liest intimation of that stance may be Archimedes famous

remark, that if he were allowed to place his lever anywhere,

he could move the world. This hints at the later stance,

which is that the earth is not a privileged vantage point,

and in fact there is no privileged vantage point. Science

seeks (or sought) to eliminate all the effects and inuences

of special locations, investigators, etc., in favor of univer-

sal laws. This has been undermined at least at the popular

level somewhat by the paradoxes of the observer and the

observed at the quantum mechanical level of science; but

the ethos remains intact.

The social critics (Max Horkheimer, Theodore Adorno,

and others) of the Frankfurt School in the 1930s were

among the rst to worry about the possibility that the

search for this particular kind of enlightenment what we

might call the universe lying spreadeagled on the dissect-

ing table was not itself neutral. They suggested that the

rhetoric of expanding human knowledge was harnessed to

a very powerful unexamined Puritanical drive towards a

pure objective truth, in the face of which ordinary human

experience would wither and die. They also suggested that

there is a complex connection between what we could call

objectivity and the treating of the world as if it were an

object.

The experience of the Nazi years (which, among other

things, led to the eeing of the Frankfurt School to Amer-

ica), and the arrival of the atomic bomb and the Cold War,

substantially undermined the claims of what has been called

the Enlightenment Project or the Age of Modernity (see

Enlightenment Project, Volume 5). The claim that reason

and science could improve the lot of humankind became

juxtaposed against the claim that it could also destroy

humankind. It was not enough to say that evil is always

possible, and reason and science could be misused; critics

began to question if there was something unreasonable in

the very framework of modernity.

The famous (or notorious) outcome of this was the

arrival of postmodernism whose antagonism to modernity

was described succinctly by the French philosopher, Jean-

Francois Lyotard, as a suspicion of all grand narratives

(Lyotard, 1984). These grand narratives included the spread

of reason over the world, universal human rights, the

redescription of the natural world in scientic terms, the

increasing recasting of natural resources by technology, and

globalization.

It is worth pointing out in this context that virtually all

the international organizations and initiatives represented

in this encyclopedia subscribe to the grand narrative tra-

dition, simply because they were either generated in the

19th century explosion of scientic networks and soci-

eties; or in the post-World War II heyday of the United

Nations.

Postmodernist thought is aligned to what is sometimes

called postnormal science (see Post-nor mal Science, Vol-

ume 5), which is an expression of a similar form of skep-

ticism about the rhetoric of neutral science. Postnormal

science interrogates this rhetoric, but also examines the

work practices of scientists, their worldview assumptions,

THE HUMAN DIMENSIONS OF GLOBAL CHANGE 3

the agenda-setting devices (e.g., why are scientists looking

at this particular part of the world and not another?) and

their communities.

Rayner and Malone, in their overview essay for this vol-

ume, describe in detail a number of the tensions between the

universalizing tendencies in the physical sciences and the

less powerful (but often similarly universalizing) counter-

strategies in the social sciences and the humanities (see

Social Science and Global Environmental Change, Vol-

ume 5).

To report on some personal experience, it was while I

was involved with the project to establish the International

Human Dimensions of Global Change Programme in the

late 1980s that the project leaders found themselves prac-

tically, as well as theoretically, faced with the implications

of the split between the worldviews of the physical sciences

and those of the social sciences and humanities. Roughly

speaking, however, the main dividing line is not between

the sciences and the social sciences; in fact, the dividing

line is within the social sciences, between those social sci-

ences whose practitioners see themselves engaged in some

form of quasi-physical science enterprise, and those that see

themselves engaged in (what for want of a better phrase)

what could be called meanings and frameworks.

The practical implications of this were (and are) that

models of global change generated by physical science

institutions treat human beings as if they were another ele-

ment in a diagram of boxes with wires. The output of certain

social sciences parts of physical geography, anthropol-

ogy, demography, etc. can t reasonably congenially into

these wiring diagrams. Social behavior, communications,

politics, and so on, are marginalized or added on as rhetor-

ical ourishes in the form of feedback loops. On the other

side of the dividing line, other social scientists and human-

ists assault the whole enterprise, i.e., that it is a symptom of

the global situation we are in (the rationalized objectica-

tion of the world) and not a solution. This kind of standoff

has complicated efforts to create international research pro-

grams that could usefully integrate the natural and the social

sciences.

THE RISE OF THE ENVIRONMENTAL

MOVEMENT

Traditionally, histories of the environmental movement

(especially in North America) begin with conservation

efforts and egregious examples of early industrial pollu-

tion, and trace its evolution through the creation of national

parks, the upsurge of interest in the 1960s through Rachel

Carsons (1963) Silent Spring, and the arrival of environ-

mental legislation in the 1970s and 1980s. This ts in with a

progressive model of a set of problems, problems identied,

an orderly political response, and so on.

In light of the above, however, I believe that a more

powerful history links environmentalism to some central

concerns of the Romantic movement in the late 18th century

about the fundamental relationship between human beings

and Nature, in particular the nature of Human Nature in a

world increasingly subjected to human inuence. Moreover,

the most compelling parts of works like Rachel Carsons

are not about this or that pesticide, but about threats to what

could be called the fabric of life, i.e., threats.

As discussed more fully in Ar t and the Environment,

Volume 5 and Liter ature and the Environment, Vol-

ume 5, the Romantic movement was driven by a desire

to overturn and reconstruct what the artists, poets, and

advanced political thinkers of the time believed to be an

outmoded, and indeed repressively dead, cosmology. This

cosmology patriarchal, hierarchical, and rational (in the

sense of a machine-like logic) was increasingly being

used to cage and tie down new expressions of human well-

being. Because it was outmoded, it was like a snake skin

or an exoskeleton that was too small externally applied,

not internally generated.

Among the metaphors applied to this cosmology were the

mask and the machine. The mask ultimately derived from

the critique of civilization fomented by the French philoso-

pher Jean-Jacques Rousseau symbolized the hypocrisy

and public demeanor of ancient powers, as well as the

emerging urban populace alienated from those powers, and

from each other. The opposite of the mask was the Man

of transparent virtue, and part of the increasingly vicious

theatre of the French Revolution (17891795) was the

relentless stripping off of, rst, the masks of rank and sta-

tion, and then, the stripping off of the masks of personal

life down to the bone.

The machine came to symbolize both the newfound

energy that could stimulate a new world of wealth creation,

but also the turning of people into creatures of the machine.

The early Industrial Revolution appeared to be like the maw

of some great creature, driving rural people away from their

farms and villages, and into hideously polluted factories

where they worked inexorably, hour after hour, day after

day. The fact that incomes and life-expectancies began

their also inexorable rise upward, and the uncomfortable

fact that supposedly happy rural life before industrialization

would not bear close examination, had less impact than the

immediately obvious relationship between the dismantling

of a seemingly organic world and the interim chaos that

ensued. Capitalism turned everything into a resource for

exploitation.

To the Romantic writers and poets William Blake,

Henry David Thoreau, Friedrich Schiller Nature becomes

many things in the wake of the extraordinary eruption of

industrialization into the world. Most obviously, it becomes

a refuge from the ills of modernizing life, which is one of

the sources for the conservation and parks movement. Less

4 SOCIAL AND ECONOMIC DIMENSIONS OF GLOBAL ENVIRONMENTAL CHANGE

obviously, it becomes a kind of comrade, or surrogate-

like human beings, Nature is under threat. Some social

ecologists see this as a central thread in modern environ-

mental politics. Another aspect of Nature is its presence

in the world as an alternative system or structure to that

being raised by human ingenuity. The fact that it has a

creative autonomy of its own, and is supremely inventive

and complex in its own right, challenges the arrogance of

technological man.

For some people, Nature becomes an entry into a spiritual

realm, and interestingly enough, it is critics like John

Ruskin and poets like Gerard Manley Hopkins, who fasten

on the intricate details of Natures design as the entry way;

and not, as earlier, on Nature as a grand symbol. In this, one

can see the growing inuence of natural science, initially on

the Victorians, and later in the synthesis that would become

the environmental movement.

However important this history may be, the real history

of the modern environmental movement, to my mind,

begins with Hiroshima, and is followed very quickly by the

revelations about the Nazi death camps. It was these events

that concentrated a growing unease about the capacity of

human beings to destroy themselves, and perhaps the world

around them. We can begin to see a change of tone in

environmental writing (still nature writing) in the 1950s

(Rachel Carsons rst successes appeared then); and it is

little remembered that the writing of Silent Spring coincided

with the rst great international grassroots environmental

action to stop the above-ground testing of nuclear weapons.

Part of what fueled that successful political activity was the

unsettling prospect of having what had hitherto been seen

as a most benign metaphor, mothers milk, poisoned; and

poisoned at a distance. Carsons pesticide poisoning at a

distance amplied and echoed that other concern.

These threats to the fabric of life to the possibility

that rents in the fabric might be caused by human igno-

rance were (in my mind) the spiritual dynamic behind the

environmental movement. In the 1970s, it went somewhat

underground, as the nuts and bolts of environmental man-

agement took center stage. I say somewhat, because it could

always be found, for example, in the concern for the poten-

tial loss of endangered species. But at various points, it has

returned in full force to revitalize environmental activism.

In the late 1980s, the prospect of a rent in the fabric of the

sky the ozone hole regenerated a whole array of envi-

ronmental actors and institutions. Similarly, if more slowly,

the prospect of irreversible climate change has begun to

concentrate the minds of many activists.

The current activist environmental movement in part

because of the political dynamic associated with global

environmental issues (symbolized by the Rio Earth Sum-

mit in 1992) appears to be more inclined to return to

the question of the role of modern industrialization and its

technological imperatives. Globalization as a phenomenon

is becoming widely seen as the interim step towards the ulti-

mate transformation of the Earth into a human enterprise.

Since multinational corporations and the rhetoric of global

free trade are propelling much of this, environmentalists

have begun making more and more sophisticated critiques

of mainstream economics.

ECONOMICS AND GLOBAL CHANGE

A central fact about contemporary life is that globalization

is rooted in a range of theories and practices that derive

from economics. This is contested by those who would

prioritize political structures such as the nation state, or

strategies of imperialism, or even social or legal or philo-

sophical forces deriving from the spread of Western models

of individualism across the globe. Nevertheless, if one sees

in economics a complex web of all of these, ultimately

justied by an almost religious belief in the virtues of the

market system whose every whim needs to be tended, then

its strength as a belief system for at least the elites in the

West and their acolytes can be hardly disputed.

Looked at historically, one of the most important aspects

of modern economic theory and practice is that it represents

the rst and most successful form of systems theory as

applied to social systems. This is part of its power; and

as will be discussed shortly, is essential to its ethical

dimension.

Economics, like the modern social sciences generally,

originated in various attempts to do for the social world

what Newton had done for the physical world, that is,

nd a set of simple laws that would explain and under-

pin a complex set of phenomena. The Scottish and French

enlightenment thinkers were haunted by this possibility;

and among the rst, and among the most controversial, of

the attempts at fullling this vision, was the provocative

work by the British writer (actually born in the Nether-

lands) Bernard de Mandeville (1714), The Fable of the

Bees.

In the Fable, Mandeville breaks with the moral and

spiritual traditions of the world, and argues that private

vice should be encouraged, because spending on luxury

goods, prostitutes, race horses, etc., generates many public

benets through employment. Here in embryo is the central

pillar of neo-conservative thought in our own day. What

made Mandevilles work so inuential was the linking

of local phenomena to global phenomena with opposite

characteristics. The social thinker is either to trace the

impacts of the local phenomena to their global outcomes

from a neutral stance (the view from nowhere), or, even

more inuentially, realize that the local phenomena can

be described quite differently when seen from a higher

vantage point. Moreover, the allocation of goods and bads

can be dissociated from any notion that the Deity bestows

them.

THE HUMAN DIMENSIONS OF GLOBAL CHANGE 5

This powerful systems model sat in the armory of the

early economists, awaiting further renement. In the mean-

time, these economists, including the physiocrats in France

(mid-18th century), and the classical economists Smith,

Malthus, and Ricardo (1750s1830s) began the task of

tracing out the transformation of Nature, people, and invest-

ments/nance/invention/buildings into land, labor, and cap-

ital. With each tracing, the relationship between economic

activity and the physical world diminished, and was re-

placed by the intricate workings of the market.

Perhaps one of the hardest things for a non-economist

(actually, for most economists as well) to recognize is

that economics does not deal with the physical world.

This became particularly true after the rst neo-classical

revolution in the mid 19th century associated with J S Mill,

William Stanley Jevons, and others; and continued into

the 20th century (with variations). Instead, it deals with

the subjective desires of individuals, as expressed through

competing demands signaled by prices, and adjudicated by

a market whose other component is supplies, drawn to the

market by the price signals, which are re-determined by

the interaction of demand and supply. More modern theory

speaks of rational allocation of scarce resources, but again,

the real world only appears in the tenuous link supplied by

an assumption of scarcity.

As a result, in contemporary economic theory and prac-

tice, the natural world enters only as it inuences prices.

If there is no price on koala bears, i.e., no one wants or

values them, they do not exist. To deal with this prob-

lem (and others) is the domain of the emerging discipline

of environmental economics (see Economics and Global

Environmental Change, Volume 5; Environmental Eco-

nomics, Volume 5). Among the tasks of this discipline are:

to nd shadow values for environmental goods that do not

show up in market prices; to develop surrogate measures

for environmental value; subject environmental goods that

currently have no legal or proprietary owners to privatiza-

tion; and generally to internalize within the market what

are called externalities.

This environmental economics approach can be com-

pared to the approach of ecological economics (see Ecolog-

ical Economics, Volume 5). Ecological economics repudi-

ates the entire superstructure of modern economic thought

polemically described above; and rather proposes to return

to the kinds of approaches characteristic of the French

physiocrats, and others. Specically, ecological economists

focus on a variety of physical aspects of human use of the

resources of the earth to sustain life.

This approach considers, among other things, what are

the physical requirements to feed human beings, sustain

agriculture year by year, harness energy, process mineral

and chemical feed stocks for industrial production, and

assess the ability of the earth systems to handle the waste

products of our activities. There are a number of problems

with this alternative approach, of which perhaps the least

serious is that there is no consistent set of measuring tools

and common language among the variety of competing ver-

sions of ecological economists. Economists such as Daly

and Cobb (1993) have been working for some years on

alternative measures of gross national product and moni-

toring systems other than price mechanisms.

More serious is the difculty of internalizing the other

economic approach, which, whatever ones views, does

currently drive the international economic system. The

price mechanism is ingrained into the workings of virtually

all decision-making processes, and acts as a fundamental

purveyor of information in current society.

Most serious of all are the intangible benets of the

standard economic approach as a moral and ethical system.

A lot that could be said about this, but I would like to

discuss two issues on this topic briey.

The rst, returning to where this section began, with

Mandevilles vision, is that one benet of the standard

economic approach is it allows people to repudiate com-

passion; or to put it another way, to feel good about being

self-interested. Obviously, technical economists (welfare

economists and the like) would protest this kind of remark;

but I am speaking here about a general cultural inuence.

Part of the neo-conservative agenda that has been so pow-

erful in recent years is an argument that people who act

compassionately towards the poor are acting inefciently.

Indeed, they are, in fact, standing in the way of the improve-

ment in the lot of the poor that would be produced by

allowing the market to operate more efciently. Everything

that interferes with the market social safety nets, public

insurance, public health care is by denition inefcient,

and thus drags down the potential for the economy. It is the

hard-hearted economic realist who is really the benefactor

of the poor.

A related moral aspect of this system is that it is sup-

posedly morally neutral. Since it derives from individual

wants, whatever those wants may be, it says nothing about

whether some wants are better than others. This classic

attack on the amorality of utilitarians is, in fact, a source of

pride to economic liberals; though they tend, paradoxically,

to bemoan the loss of conservative values like family life

that their system is happily destroying.

The second (and related) issue is that not only are the ori-

gins of those wants now subjected to gross manipulation by

corporate advertising; but at the heart of the system for a

variety of obscure historical and sociological reasons one

can nd a powerful model of the human which is being pro-

pounded. In this view, contrary to virtually all ethical and

spiritual traditions in the world, human beings are funda-

mentally self-interested, and possessed of innite desires

which can never be fully satised; and that rather than

try and eliminate these desires, they should be encour-

aged. Similarly, consumption patterns are now fully seen

6 SOCIAL AND ECONOMIC DIMENSIONS OF GLOBAL ENVIRONMENTAL CHANGE

as expressions of one s personality. The rise of fashion, the

need for status differentiation in an increasingly homog-

enized world, and the transformation of the citizen into a

consumer rather than a producer, have all contributed to the

seemingly unlimited growth in consumption in developed

countries.

As has been stated by numerous writers, the spread of this

in nitely desiring consumer model to the developing world

is doubly troubling. Analysts of the so-called ecological

footprint the amount of extra resources needed to ser-

vice developed country growth already argue that we will

need three or four new earths to service a world population

carrying around in its heads the lifestyles of North America.

MANAGING THE EARTH?

In the meantime, if we look at actual production patterns on

the earth, designed to service this population, we can see

very important trends in the technical means being deployed

in the reordering of the planet for human ends.

Approximately 40% of land-based net primary produc-

tion (that is, plant-generated material), and over 25% of

marine net primary production is now being diverted or

rearranged for human use. Much of this is taken by the

domestication of livestock, the harvesting of higher animals

and sh, and agriculture. This is completely unprecedented.

What is happening around the world is essentially a

restructuring of ecosystems in order to maximize produc-

tion, primarily through creating systems according to at

least ve rules.

1. organize for harvesting of natural products at the peak

of productivity. The productive peak for many natural

ecosystems is at the end of the juvenile phase;

2. concentrate for easier planting/monitoring/harvesting;

3. replace/buffer/enhance ecosystem processes;

4. add value at, and beyond, the farm gate;

5. suppress extra-market externalities.

Here are two examples of some of these rules in

operation.

One example is sh farming. Worldwide natural sh

stocks are in deep trouble, with something like 34% of

sh species threatened with extinction. One solution is

intensi ed sh farming in captive tanks. It is calculated

that one in four sh that reaches market today comes from

a sh farm. The problem is that a sh farm is a monoculture,

and all the supporting services have to be brought in from

the outside sh farmers are now competing with poultry

and pork producers for grain and protein meal supplements,

such as soybeans. These farms also produce high levels of

waste, they suffer from outbreaks of disease, and forms of

chemical pollution.

This is exactly the same situation as in monocultural

agriculture. The problem with the average managed eld

is that it is trying to turn back into a meadow or a forest.

Today s agriculture requires immense inputs of pesticides,

herbicides, gasoline for tractors, etc., in order to create an

outdoor factory. The most recent types of high-yield corn

require that all the microorganisms in the surrounding soil

be killed off. This kind of agriculture is becoming more and

more expensive, in part because the weeds and the bugs,

i.e., the ecological precursors of a return to a meadow, are

being chemically and biologically selected for resistance to

whatever the latest crop strategy is.

A similar process has been underway for many years in

forestry.

Rule one means that crops, trees and sh must be

harvested in the juvenile phase and before they level off as

adults, at which point it is economically inef cient for them

to just be sitting around. This means that there are no older

age cohorts left, which also means that the regeneration

through decomposition disappears. If you have no old trees,

you have no carbon being returned to the soil, no place for

insects and other decomposers to nestle in, and so on.

Rule two, which is essential to agriculture and mining,

concentration and simpli cation means, in living systems,

that there is no diversity, and that makes the system vul-

nerable to catastrophic attack by virus, bug, plague, weed,

or genetic mutation or rapid climate change.

Rule three means that all the processes of energy cycling,

nutrient creation, removal of wastes, and so on, have to

be imported into the simpli ed ecosystem from outside. In

order to do that, energy is required, in addition to resources

from somewhere else, which means that some other high-

quality ecosystem (or stock of fossil fuels) is being tapped

into and degraded. It is based on the assumption that there

is always somewhere else left to go to get the supplies

needed to feed the arti cial ecosystem.

Rule four, which is well known to farmers, means that

the primary production of the ecosystem is virtually worth-

less it is essentially a host for what will happen next.

A potato is worth nothing compared to barbacue potato

chips. That is where the money is. A particularly ironic

example of this came recently during the collapse of the

East Coast Fisheries. One of the largest Canadian sh pro-

cessors, which was instrumental in destroying the sheries,

and has now moved on to the South China Sea, turned its

attention to sh species that it had never bothered to sh

for before, ground them up, and then rebuilt them as sh

ngers in the shapes of star sh and seahorses, and was sell-

ing them at great pro t to Colonel Sanders and other fast

food outlets in the US.

Rule ve, which is perhaps the most important, is an

attempt to eliminate the environment as a part of economic

costs of production and marketing. The best example of

this the one that is causing global warming is the sup-

pression of geography to enable the smooth running of free

trade. Free trade, or if you like, international free markets,

THE HUMAN DIMENSIONS OF GLOBAL CHANGE 7

depend upon the ability to ship goods to any place in the

world without friction or at very low friction. Distance from

one place to another is no longer to be a consideration. The

reason this can be done more or less is the low price