Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

Birnie and Boyle (2009) - International Law and The Environment

Enviado por

chinahxcTítulo original

Direitos autorais

Formatos disponíveis

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Birnie and Boyle (2009) - International Law and The Environment

Enviado por

chinahxcDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

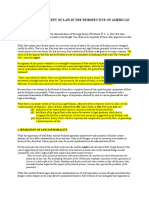

i1iv.1io.i i.w .

u 1ui ivivomi1

This page intentionally left blank

international

law and the

environment

Tird Edition

patricia birnie

alan boyle

catherine redgwell

1

3

Great Clarendon Street, Oxford ox2 6uv

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford.

It furthers the Universitys objective of excellence in research, scholarship,

and education by publishing worldwide in

Oxford New York

Auckland Cape Town Dar es Salaam Hong Kong Karachi

Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Nairobi

New Delhi Shanghai Taipei Toronto

With om ces in

Argentina Austria Brazil Chile Czech Republic France Greece

Guatemala Hungary Italy Japan Poland Portugal Singapore

South Korea Switzerland Tailand Turkey Ukraine Vietnam

Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press

in the UK and in certain other countries

Published in the United States

by Oxford University Press Inc., New York

P. W. Birnie, A. E. Boyle and C. Redgwell 2009

Te moral rights of the authors have been asserted

Crown copyright material is reproduced under Class Licence

Number C01P0000148 with the permission of OPSI

and the Queens Printer for Scotland

Database right Oxford University Press (maker)

First published 2009

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced,

stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means,

without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press,

or as expressly permitted by law, or under terms agreed with the appropriate

reprographics rights organization. Enquiries concerning reproduction

outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department,

Oxford University Press, at the address above

You must not circulate this book in any other binding or cover

and you must impose the same condition on any acquirer

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

Data available

Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data

Birnie, Patricia W.

International law and the environment / Patricia Birnie, Alan Boyle,

Catherine Redgwell.3rd ed.

p. cm.

Includes index.

ISBN 9780198764229

1. Environmental law, International. I. Boyle, Alan E. II. Redgwell,

Catherine. III. Title.

K3383.B37 2009

344.046dc22 2008048609

Typeset by Newgen Imaging Systems (P) Ltd., Chennai, India

Printed in Great Britain

on acid-free paper by

Ashford Colour Press Ltd, Gosport, Hampshire

ISBN 978-0-19-876422-9

1 3 3 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

vvii.ci

Te development of modern international environmental law, starting essentially in

the 1960s, has been one of the most remarkable exercises in international lawmaking,

comparable to the law of human rights and international trade law in the scale and

form it has taken. Since the Rio Conference in 1992, the subject as a whole has come of

age. Its gestation may have been slow, but international environmental law has proved

a very vigorous plant. If the 1980s and 1990s are best remembered for treaty conges-

tion because of the large number of multilateral environmental agreements under

negotiation, the frst decade of the new millennium has seen an unparalleled growth

in the environmental jurisprudence of international tribunals. No longer is it neces-

sary to squeeze every drop of life out of the immortal trio of arbitrationsBering Sea

Fur Seals, Trail Smelter and Lac Lanouxwhich have sustained international environ-

mental law throughout most of its existence.

In this third edition we have concentrated on revising and updating the text rather

than adding signifcant amounts of new material. A small number of treaties are cov-

ered for the frst time, but the principal additions are from the case law of the ICJ,

the ITLOS, the WTO, international arbitral awards, and decisions of human-rights

courts and commissions. Te treatment of climate change and the Kyoto Protocol has

been expanded, as has the introductory chapter. We have also taken the opportunity

to reorganize some chapters and relocate material to places where it now seems more

appropriate, including the waste bin, but the basic structure of the book remains the

same. Our intention has been to cover signifcant developments up to mid-2008, but

in such a large and ever-expanding topic it is impossible to be comprehensive, and

there is much more that could be said on everything. Te book remains primarily

an introduction to the general corpus of international environmental law, including

the lawmaking and regulatory processes, approached from the perspective of gener-

alist international lawyers rather than specialist environmental lawyers. Experience

of international litigation suggests that this is the right way to approach the subject, at

least in that context.

Te most signifcant change has been the retirement from active participation

by Patricia Birnie, co-author of the frst and second editions. Her inspiration and

unrivalled understanding of the law and context of international protection of the

environment have been indispensable from the very beginning of what has proved a

far larger project than was ever imagined. In her place, Catherine Redgwell has taken

over responsibility for revising Chapters 11 and 12, as well as Chapter 14, originally

drafed by Tom Schoenbaum. In order to keep abreast of the vitally important and fast

developing subject of climate change we were very pleased when Navraj Ghaleigh of

the University of Edinburgh agreed to deploy his expertise on a substantial revision of

what is now Chapter 6.

vi preface

We are indebted to several colleagues and friends for sharing their knowledge on

various topics, but especial thanks are due to Lorand Bartels, Bradnee Chambers,

Louise de La Fayette, Bill Edeson, Sebastian Lopez Escarcena, David Freestone, James

Harrison, Na Li, and Richard Tarasofsky.

As always we have been well served by a series of research assistants who have

greatly eased the task of keeping on top of new material. Safya Ali, Daniela Diz,

Pierre Harcourt, Bonnie Holligan, Sam McIntosh, Frida Petersson, Danielle Rached,

Meerim Razbaeva, Christian Schall, Felicity Stewart, Emmanuel Ugirashebuja, and

Andreas Woitecki, all of Edinburgh University, and Silvia Borelli of University College

London, have been a great help. We are very grateful to them all, and to our many PhD,

LLM and LLB students for asking the questions that keep any author alert and con-

scious. Eleanor Williams of OUP has provided timely and above all patient support

for authors who may at times have seemed unlikely ever to deliver, and our thanks go

to all those working for OUP who have made this edition happen.

Alan Boyle and Catherine Redgwell

31 July 2008

co1i1s

Abbreviations: Journals and Reports xi

Table of Cases xix

Table of Major Treaties and Other Instruments xxvii

1 i1iv.1io.i i.w .u 1ui ivivomi1 1

1 Introduction 1

2 Lawmaking Processes and Sources of Law 12

3 Overview 37

2 i1iv.1io.i coviv.ci .u 1ui iovmUi.1io oi

ivivomi1.i i.w .u voiicv 43

1 Introduction 43

2 Te Development of International Environmental Policy 48

3 Te UN and Environmental Governance 38

4 Other International Organizations 71

3 International Regulatory Regimes 84

6 Scientifc Organizations 99

7 Non-Governmental Organizations 100

8 Conclusions 103

3 vicu1s .u oniic.1ios oi s1.1is cocivic

vvo1ic1io oi 1ui ivivomi1 106

1 Introduction 106

2 Sustainable Development: Legal Implications 113

3 Principles of Global Environmental Responsibility 128

4 Prevention of Pollution and Environmental Harm 137

3 Conservation and Sustainable Use of Natural Resources 190

6 Military Activities and the Environment 203

7 Conclusions 208

4 i1ivs1.1i iiovcimi1: s1.1i visvosiniii1v, 1vi.1v

comvii.ci, .u uisvU1i si11iimi1 211

1 Introduction 211

viii contents

2 State Responsibility for Environmental Damage 214

3 Treaty Compliance 237

4 Settlement of International Environmental Disputes 230

3 Conclusions 266

3 o-s1.1i .c1ovs: ivivomi1.i vicu1s,

ii.niii1v, .u cvimis 268

1 Introduction 268

2 Human Rights and the Environment 271

3 Transboundary Environmental Rights 303

4 Harmonization of Environmental Liability 316

3 Corporate Environmental Accountability 326

6 Environmental Crimes 329

7 Conclusions 334

6 ciim.1i cu.ci .u .1mosvuivic voiiU1io 333

1 Introduction 333

2 Transboundary Air Pollution 342

3 Protecting the Ozone Layer 349

4 Te Climate Change Regime 336

3 Conclusions 377

7 1ui i.w oi 1ui si. .u vvo1ic1io oi 1ui m.vii

ivivomi1 379

1 Introduction 379

2 Customary Law and the 1982 UNCLOS 386

3 Regional Protection of the Marine Environment 390

4 Marine Pollution from Ships 398

3 Pollution Incidents and Emergencies at Sea 423

6 Responsibility and Liability for Marine Pollution Damage 430

7 Conclusions 441

8 i1iv.1io.i vicUi.1io oi 1oxic sUns1.cis 443

1 Introduction 443

2 International Regulation of Toxic Chemicals 443

3 Protection of the Marine Environment from Toxic Substances 431

contents ix

4 International Trade in Hazardous Substances 473

3 Conclusions 486

9 Ucii.v iivcv .u 1ui ivivomi1 488

1 Introduction 488

2 Te International Regulation of Nuclear Energy 492

3 Control of Transboundary Nuclear Risks 308

4 State Responsibility for Nuclear Damage 316

3 Civil Liability for Nuclear Damage 320

6 Conclusions 333

10 i1iv.1io.i w.1ivcoUvsis: ivivomi1.i

vvo1ic1io .u sUs1.i.nii Usi 333

1 Introduction 333

2 Protection of Watercourse Environments 347

3 Regional Cooperation and Environmental Regulation 372

4 Conclusions 380

11 cosivv.1io oi .1Uvi, icosvs1ims, .u niouivivsi1v 383

1 Introduction 383

2 Concepts of Nature Conservation and Natural Resources 383

3 Te Role of Law in the Protection of Nature 393

4 Codifcation and Development of International Law on

Nature Protection 602

3 Te Convention on Biological Diversity 612

6 Conclusions 648

12 cosivv.1io oi micv.1ovv .u i.u-n.siu

sviciis .u niouivivsi1v 630

1 Introduction 630

2 Implementation of Principles and Strategies through

Conservation Treaties 631

3 Signfcance and Efectiveness of the Major Global

Wildlife Conventions 671

4 Post-UNCED Instruments for Conservation of

Nature and Biodiversity 692

3 Te Regional Approach 696

x contents

6 Coordination of Conventions and Organs 697

7 Conclusions 698

13 cosivv.1io oi m.vii iivic visoUvcis

.u niouivivsi1v 702

1 Introduction 702

2 Jurisdiction over Fisheries and Marine Mammals 706

3 Te Development of International Fisheries Regimes 711

4 Te 1982 UN Convention on the Law of the Sea 714

3 Post-UNCLOS Developments 730

6 Conservation of Marine Biodiversity 744

7 Conclusions 731

14 i1iv.1io.i 1v.ui .u ivivomi1.i vvo1ic1io 733

1 Introduction 733

2 Te Multilateral Trading System 736

3 Multilateral Environmental Agreements and Trade Restrictions 766

4 Trade Restrictions to Protect Resources beyond National Jurisdiction 769

3 Trade Restrictions to Protect the Domestic Environment 778

6 Pollution Havens: Trade Restrictions to Improve the

Environment of Other Countries 788

7 Te Export of Hazardous Substances and Wastes 793

8 Environmental Taxes 796

9 Te TRIPS Agreement and the Biodiversity Convention 801

10 Conclusions 809

Bibliography 811

Index 833

.nnvivi.1ios: ,oUv.is

.u vivov1s

ACHPR African Convention/Commission on Human and Peoples

Rights

AC Appeal Cases (House of Lords) (UK)

ACOPS Advisory Committee on Pollution of the Sea

All ER All England Reports

AFDI Annuaire Franais de Droit International

AIR All India Reports

AJIL American Journal of International Law

ALJ Australian Law Journal

ALJR Australian Law Journal Reports

ALR Australian Law Reports

Ann Droit Mar &

Ocanique

Annuaire de Droit Maritime et Ocanique

Ann Rev Ecol Syst Annual Review of Ecological Systems

Ann Rev Energy &

Env

Annual Review of Energy and Environment

Ann Inst DDI Annuaire de lInstitut de Droit International

Ann Suisse DDI Annuaire Suisse de Droit International

Am UJILP American University Journal of International Law and

Politics

ASIL American Society of International Law Proceedings

AULR American University Law Review

AYIL Australian Yearbook of International Law

BAT Best Available Techniques

BEP Best Environmental Practice

BFSP British and Foreign State Papers

Boston CICLJ Boston College International and Comparative Law Journal

BISD Basic Instruments and Selected Decisions of the GATT

Boston Coll Env

Af LR

Boston College Environmental Afairs Law Review

BTA Border Tax Adjustment

Brooklyn JIL Brooklyn Journal of International Law

xii abbreviations: journals and reports

Burhenne International Environmental Law: Multilateral Treaties, ed.

W. Burhenne (Berlin, 1974)

BYIL British Yearbook of International Law

Colorado JIELP Colorado Journal of International Environmental Law and

Policy

Columbia JTL Columbia Journal of Transnational Law

Columbia JEL Columbia Journal of Environmental Law

CLB Commonwealth Law Bulletin

CLP Current Legal Problems

CLR Commonwealth Law Reports

CMLR Common Market Law Review

Columbia HRLR Columbia Human Rights Law Review

Cornell ILJ Cornell International Law Journal

CWILJ California Western International Law Journal

CWRJIL Case Western Reserve Journal of International Law

CYIL Canadian Yearbook of International Law

CBD Convention on Biological Diversity

CCAMLR Convention for the Conservation of Antarctic Marine Living

Resources

CDM Clean Development Mechanism

CEC Commission for Environmental Co-operation

CITES Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species

CDM Clean development mechanism

CEC Commission for Environmental Co-operation

CITES Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species

COLREGS Collision Regulations

COP Conference of the Parties

CSCE Conference on Security and Cooperation in Europe

CTE Committee on Trade and Environment

Dal LJ Dalhousie Law Journal

Den JILP Denver Journal of International Law and Politics

DLR (AD) Dominion Law Reporter (Appellate Division) (Bangladesh)

Duke LJ Duke Law Journal

ECHR European Court of Human Rights Reports

ECJ European Court of Justice

ECR European Court Reports

abbreviations: journals and reports xiii

EHRR European Human Rights Reports

EJIL European Journal of International Law

ELQ Environmental Law Quarterly

ELR European Law Review

DSB Dispute Settlement Body

Emory Int LR Emory International Law Review

Envtl L Environmental Lawyer

Ency of Pub Int L Encyclopaedia of Public International Law

EPL Environmental Policy and Law

ETS Council of Europe Treaty Series

Eur Env LR European Environmental Law Review

Eur J of Crime,

Crim L & Crim Just

European Journal of Crime, Criminal Law & Criminal

Justice

EC European Community

ECHR European Convention/Court of Human Rights

ECOSOC Economic and Social Committee

EEZ Exclusive Economic Zone

EFZ Exclusive Fishery Zone

EIA Environmental Impact Assessment

EMEP Programme for Monitoring and Evaluation of Long-range

Transmission of Air Pollutants in Europe

EPA Environmental Protection Agency

EU European Union

FAO Food and Agriculture Organization

FC Federal Courts (Canada)

FNI Fishing News International

Fordham ELJ Fordham Environmental Law Journal

GATT General Agreement on Tarifs and Trade, 1947

Georgia LR Georgia Law Review

Georgetown IELR Georgetown International Environmental Law Review

GYIL German Yearbook of International Law

Hague YIL Hague Yearbook of International Law

Harv ELR Harvard Environmental Law Review

Harv HRYB Harvard Human Rights Yearbook

FSIC Flag State Implementation Committee

xiv abbreviations: journals and reports

GEF Global Environmental Facility

GESAMP Group of Experts on Scientifc Aspects of Marine Pollution

Harv ILJ Harvard International Law Journal

Harv LR Harvard Law Review

HRLJ Human Rights Law Journal

HRR Human Rights Reports

Hum & Ecol Risk

Assessment

Human and Ecological Risk Assessment

HMS Highly migratory species

ICJ International Court of Justice

ICLQ International and Comparative Law Quarterly

Idaho LR Idaho Law Review

IJECL International Journal of Estuarine and Coastal Law

IJMCL International Journal of Marine and Coastal Law

ILA International Law Association

ILC International Law Commission

ILM International Legal Materials

ILR International Law Reports

Indian JIL Indian Journal of International Law

Int Afairs International Afairs

Inter-American YB

on Hum Rts

Inter-American Yearbook on Human Rights

Int Env L Reps International Environmental Law Reports

Int Org International Organisation

Int Orgs LR International Organisations Law Review

Ital YIL Italian Yearbook of International Law

ITLOS International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea

IUCN Bull International Union for the Conservation of Nature Bulletin

IACHR Inter-American Court of Human Rights

IAEA International Atomic Energy Agency

ICCPR International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights

ICES International Council on Exploration of the Seas

ICESCR International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural

Rights

ICRW International Convention for the Regulation of Whaling

IFC International Finance Corporation

abbreviations: journals and reports xv

INC Intergovernmental Negotiating Committee

INSC International North Sea Conference

IOPC International Oil Pollution Compensation Fund

IPCC Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change

ISBA International Seabed Authority

ITTA International Tropical Timber Agreement

ITTO International Tropical Timber Organization

Jap Ann IL Japanese Annual of International Law

JEL Journal of Environmental Law

J Env & Devmnt Journal of Environment and Development

J Eur Env & Plng L Journal of European Environmental and Planning Law

JIEL Journal of International Economic Law

JIWLP Journal of International Wildlife Law and Policy

JIELP Journal of International Environmental Law and Policy

JLS Journal of Law and Society

JMLC Journal of Maritime Law and Commerce

Jnl of Bus Admin Journal of Business Administration

JPEL Journal of Planning and Environmental Law

JPL Journal of Planning Law

J Transnatl L & Pol Journal of Transnational Law and Policy

JWT Journal of World Trade Law

LGERA Local Government and Environment Reports of Australia

LJIL Leiden Journal of International Law

LNTS League of Nations Treaty Series

Loyola ICLJ Loyola University International and Comparative Law

Journal

LOSB Law of the Sea Bulletin

Mar Poll Bull Marine Pollution Bulletin

Max Planck

YbUNL

Max Planck Yearbook of United Nations Law

McGill LR McGill Law Review

Melb ULR Melbourne University Law Review

Mich JIL Michigan Journal of International Law

Minn J Global

Trade

Minnesota Journal of Global Trade

xvi abbreviations: journals and reports

MLJ Malaysia Law Journal

MLR Modern Law Review

ND New Directions in the Law of the Sea (Dobbs, Ferry, 1974- )

NILR Netherlands International Law Review

NLB Nuclear Law Bulletin

Nordic JIL Nordic Journal of International Law

NRJ Natural Resources Journal

NYIL Netherlands Yearbook of International Law

NYJILP New York Journal of International Law and Policy

NY Law School LR New York Law School Law Review

NYUEnvLJ New York University Environmental Law Journal

NZLR New Zealand Law Reports

O&C Man Ocean and Coastal Management

Ocean YB Ocean Yearbook

ODIL Ocean Development and International Law

OGTLR Oil and Gas Taxation Law Review

OJ Of cial Journal (of the European Community)

Oregon LR Oregon Law Review

OPN Ocean Policy News

OsHLJ Osgoode Hall Law Journal

PACE ELR Pace Environmental Law Review

Otago LJ University of Otago Law Journal

PCIJ Permanent Court of International Justice Reports

Proc ASIL Proceedings of the American Society of International Law

Pub.Admin Public Administration

RBDI Revue Belge de Droit International

RECIEL Review of European Community and International Environ-

mental Law

Rev Int de Droit

Pnal

Revue International de Droit Pnal

Rev jurid de lenv Revue juridique de lenvironment

Rev Espanola DI Revista Espanola Derecho Internacional

Rev Eur Droit de

lEnv

Revue Europen du Droit de lEnvironnement

RGDIP Revue Gnral de Droit International Public

RIAA Reports of International Arbitration Awards

abbreviations: journals and reports xvii

Ruster and Simma International Protection of the Environment, ed. B. Ruster

and B. Simma, (Dobbs Ferry, 1975- )

SALJ South African Law Journal

Scal LR Southern California Law Review

SCC Supreme Court Cases (India)

S Ct Supreme Court (US)

San Diego LR San Diego Law Review

Stanford JIL Stanford Journal of International Law

Stan ELJ Stanford Environmental Law Journal

Sydney LR Sydney Law Review

Texas ILJ Texas International Law Journal

Tulane ELJ Tulane Environmental Journal

Tulane JICL Tulane Journal of International and Comparative Law

UBCLR University of British Columbia Law Review

UCLA J Envtl L &

Poly

University of California at Los Angeles Journal of Environ-

mental Law and Policy

UCLALR University of California at Los Angeles Law Review

UKTS United Kingdom Treaty Series

UNCLOS United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea, 1982

UN Doc United Nations Document

UNGA United Nations General Assembly

UNGAOR United Nations General Assembly Of cial Records

UNHRC United Nations Human Rights Commission

UN Jurid YB United Nations Juridical Yearbook

UN Leg Ser United Nations Legislative Series

UNTS United Nations Treaty Series

U Penn LR University of Pennsylvania Law Review

US United States Reports

USPQ United States Patents Quarterly

UST United States Treaties

UTLJ University of Toronto Law Journal

Vand JTL Vanderbilt Journal of Transnational Law

Va Envtl LJ Virginia Environmental Law Journal

VJIL Virginia Journal of International Law

VUWLR Victoria University of Wellington Law Review

Wash & Lee LR Washington and Lee Law Review

xviii abbreviations: journals and reports

Wis ILJ Wisconsin International Law Journal

WLR Weekly Law Reports (England)

Wm & Mary Envtl

L & Pol Rev

William and Mary Environmental Law & Policy Review

Yale LJ Yale Law Journal

Ybk of the AAA Yearbook of the Hague Academy of International Law

YEL Yearbook of European Law

YbIEL Yearbook of International Environmental Law

YBILC Yearbook of the International Law Commission

ZARV Zeitschrif fr Auslndisches und fentliches Recht und

Vlkerrecht

1.nii oi c.sis

Administration of the Foreign Investment Review

Act, GATT BISD (30th Supp.) 140, (1984) . . .

739

Advisory Opinions on the Legality of the Use

by a State of Nuclear Weapons in Armed

Confict, ICJ Reports (1996) 66 (WHO) and

226 (UNGA). See Nuclear Weapons Advisory

Opnion

Advisory Opinion on the Interpretation of the

American Declaration on the Rights and

Duties of Man (1989) IACHR Series A, No. 10

. . . 273

Aegean Sea Continental Shelf Case, ICJ Reports

(1978) 3 . . . 20

Aguinda v. Texaco Inc. 830 F.Supp. 282 (1994);

943 F.Supp.623 (1996) . . . 308, 309, 313

Air Services Arbitration, 34 ILR (1978) 304 . . .

238, 777

Alabama Claims Arbitration (1872) 1 Moores

Int. Arbitration Awards, 483 . . . 148

Al-Adsani v. UK (2001) 123 ILR 24 . . . 236

Albert v. Frazer Companies Ltd. [1937] 1 DLR.

39 . . . 308

Allen v. Gulf Oil [1981] 1 All ER 333 . . . 323

Antonio Gramsci Case, IOPC Fund 1st Annual

Report (1990) 23 . . . 230, 437, 438

Apirana Mahuika et al v. New Zealand (2000)

ICCPR No. 347/1993 . . . 287, 293

Asahi Metal Co. Ltd. v. Superior Court, 480 US

102 (1987) . . . 313

Asbestos Case see EC-Measures Afecting

Asbestos and Asbestos-Containing Products

Association Greenpeace France v. France,

Novartis and Monsanto (Transgenic maize

case) (1998) 2/IR Recueil Dalloz 240 . . . 162

Athanassoglou v. Switzerland (2001) 31 EHRR

13 . . . 290

Augsburg v. Federal Republic of Germany

(WaMsterben case) (1988) 103 Deutsches

Verwaltungsblatt 232 . . . 162

Axen v. Federal Republic of Germany (1983)

ECHR Ser. A/72 . . . 309310

Barcelona Traction, ICJ Reports (1970) 3 . . . 131,

233, 136

Balmer-Schafroth v. Switzerland (1997-IV)

ECHR . . . 290

Bandhua Mukti Morcha v. Union of India (1984)

3 SCC 161 . . . 139, 276, 297

Bankovic v. Belgium (2002) 41 ILM 317 . . . 299

Beef Hormones case see EC-Measures

Concerning Meat and Meat Products

Behring Sea Fur Seals Arbitration (1898) 1

Moores Int. Arbitration Awards 733, repr. in 1

Int.Env.L.Reps (1999) 43 . . . 38, 180181, 190,

193, 226

Belgian Family Allowances (Allocations

Familiales) GATT BISD (1st Supp.) 39

(1933) . . . 737

Belgian Waste Case See EC v. Belgium

Belize Alliance of Conservation Non-

Governmental Organizations v. Dept. of

Environment (2003) JCPC . . . 174

Bhopal Case See In re Union Carbide

Corporation Gas Plant Disaster at Bhopal

Biotech Case See EC-Measures Afecting the

Approval and Marketing of Biotech Products

Blue Circle Industries Pic v Ministry of Defence

[1998] 3 All ER 383 . . . 324

Bluefn Tuna Cases See Southern Bluefn Tuna

Cases

Bond Beter Leefmilieu Vlaanderen VZW-

Belgium, Compliance Committee, UNECE/

MP.PP/C.l/2006/4/Add.2 (2006) . . . 294

Border Tax Adjustments, GATT BISD (18th

Supp.) 97, (1972) . . . 799

Bordes v. France, UNHRC No. 643/1993, Rept.

Human Rights Committee (1996) GAOR

A/31/40, vol. . . . 284, 283

Bosnian Genocide Case, ICJ Reports (2007) . . .

148, 133, 214, 228

BP v. Libya, 33 ILR (1973) 297 . . . 191

British South Africa Company v. Compania de

Moambique [1893] AC 602 . . . 308

Brun v. France (2006) ICCPR Communication

No. 1433/2006 . . . 301

Burnie Port Authority v. General Jones Pty. Ltd.

(1994) 179 CLR 320 . . . 219

Bystre Deep-water Navigation Canal

Findings and Recommendation with regard

to compliance by Ukraine, ECE/MP.PP/

C.l/2003/2/Add.3 (2003) . . . 292

Cambridge Water Co. v. Eastern Counties

Leather plc [1994] 1 All ER 33 . . . 219

Canada Beer Cases See Import, Distribution,

and Sale of Alcoholic Drinks by Canadian

Provincial Marketing Agencies

xx table of cases

Canadian Wildlife Federation v. Minister of

Environment and Saskatchewan Water Comp.

(1989) 3 Federal Court 309 (TD) . . . 168

Caesar v. Trinidad and Tobago (2003) IACHR

Sers. C, No. 123 . . . 301

Cassis de Dijon Case See Rewe-Zentral AG v.

Bundesmonopolverwaltung fr Branntwein

Certain Phosphate Lands in Nauru, ICJ Reports

(1993) 322 . . . 121, 138

Charan Lal Sahu v. Union of India (1986) 2 SCC

176 . . . 283, 298

Chassagnou v. France, ECHR (1999); 3 Int.Env.

LR (2001) . . . 287

Chorzow Factory Case (Indemnity) PCIJ, Ser. A,

No. 8/9 (1927); ibid. No. 17 . . . 27, 226, 228,

238, 237

City of Philadelphia v. New Jersey, 437 US 617

(1978) . . . 796

CME Czech Republic B.V. v. Te Czech Republic

(2001) UNCITRAL . . . 327

Comitato Communa Bellis e Sanctuario v.

Commune di Ostiglia (2006) Consiglio di

Stato No. 3760/2006 . . . 297

Commission v. Ireland (MUX Plant Case) ECR

[2006] 14633 . . . 298

Commonwealth of Australia v. State of

Tasmania, 46 ALR (1983) 623 . . . 298, 680

Commonwealth of Puerto Rico v. SS Zoe

Colocotroni, 436 F. Supp. 1327 (1978); 628 F.

2d. 632 (1980) . . . 230, 324, 437, 438

Community of San Mateo de Huanchor v. Peru,

Case 304/03, Report No. 69/04, Inter-Am

CHR, OEA/Ser.L/V/II.122 Doc. 3 rev. 1, 487

(2004) . . . 284

Connelly v. RTZ Corp. plc [1998] AC 834 . . . 309,

310

Continental Shelf Case (Italian Intervention) ICJ

Reports (1984) 3 . . . 233

Corfu Channel Case, ICJ Reports (1949) 1 . . . 27,

144, 148, 133, 182, 183, 106, 213, 217, 221, 222,

413, 417, 423, 479, 316, 372

Cyprus v. Turkey [2001] ECHR No. 23781/94 . . .

229

Dagi v. Broken Hill Proprietary Co. Ltd. (1997) 1

Victoria Reps. 428 . . . 308, 310

Dalma Orchards Armenia, Compliance

Committee, UNECE/MP.PP/C.l/2006/2/Add.l

(2006) . . . 293

Danish Bottles Case See EC v. Denmark

Defenders of Wildlife Inc. v. Endangered Species

Authority, 639 F. 2d 168 (1981) . . . 298

Denev v. Sweden, ECHR App. No. 12370/86

(1989); 3 Int. Env,LR (2001) . . . 287

Diamond v. Chakrabarty, 447 US 303

(1980) . . . 806

Diplomatic and Consular Staf in Tehran Case,

ICJ Reports (1980) 3 . . . 148, 214, 316, 363

Diversion of Water from the Meuse Case, PCIJ

Ser. A/B, No. 70 . . . 333

Dombo Beheer v. Netherlands (1993) ECHR Sers.

A/274 . . . 310

Donauversinkung Case, 1 Int.Env.LR (1999) 444

. . . 181

Drozd and Janousek v. France and Spain (1992)

ECHR Sers. A/240 . . . 299

Duke Power Co. v. Environmental Study Group,

438 US 39 (1978) . . . 324

Dunne v. NW Gas Board [1964] 2 QB 603 . . .

219, 323

East Timor Case, ICJ Reports (1993) 2 . . . 131,

233

EC - Biotech Case - See EC-Measures Afecting

the Approval and Marketing of Biotech

Products

EC - Measures Concerning Meat and Meat

Products [Beef Hormones Case] WTO

Appellate Body (1997) WT/DS26/AB/R . . .

28, 108, 109, 133, 136, 138, 160, 174, 781, 782,

783

EC - Measures Afecting Asbestos [Asbestos

Case] WTO Appellate Body (2001) WT/

DS133/AB/R . . . 108, 234, 738, 761, 763, 763,

766, 773, 774

EC - Measures Afecting the Approval and

Marketing of Biotech Products [EC-Biotech

Case] WTO Panel (2006) WT/DS29l/R, WT/

DS292/R, WT/DS293/R . . . 647, 763, 776, 780,

781

EC - Trade Descriptions of Sardines, WTO

Appellate Body (2002) WT/DS23l/AB/R . . .

782

EC v. Belgium, ECJ No. 2/90 [1993], 1 CMLR

(1993) 363 [Belgian Waste Case] . . . 796

EC v. France, ECJ No.182/89 [1990], ECR-I

[1990] 4337 . . . 298

EC v. France, ECJ Case C-239/03 [2004] . . . 298

EC v. Denmark, CJ No. 382/86 [1988]; ECR

[1988] 4607; [1989] 1 CMLR 619 [Danish

Bottles Case] . . . 783, 783

Emilio Agustin Mafezini v Te Kingdom of

Spain, ICS ID No. ARB/97/7 (2000) . . . 327

Environmental Defence Society v. South

Pacifc Aluminium (No. 3) (1981) 1 NZLR

216 . . . 297

Environmental Defense Fund Inc. v. Massey 986

F. 2d 328 (1993) . . . 168

table of cases xxi

Ex parte Allen, 2 USPQ 1423 (1987) . . . 806

Fadeyeva v. Russia [2003] ECHR 376 . . . 283,

284, 320

Farooque v. Government of Bangladesh (1997) 49

DLR (AD) 1 . . . 297

Fisheries Jurisdiction Cases (UK and Germany

v. Iceland) ICJ Reports (1974) 3 and 173 See

Icelandic Fisheries Cases

Fogarty v. UK (2001) 123 Int LR 34 . . . 23, 138

Fredin v. Sweden, ECHR, Sers. A/192 (1991); 3

Int.Env.LR (2001) . . . 287

Free Zones of Upper Saxony and the District of

Gex Case (Second Phase) PC1J Ser. A, No. 24

(1930); (Merits) Ser. A/B, No. 46 (1932) . . . 27

Friends of the Earth v. Laidlaw, 120 SCt 693

(2000) . . . 297

Fundepublico v. Mayor of Bugalagrande (1992)

ECOSOC, UN Doc. E/CN.4/Sub.2/1993/7, 16

. . . 297

Gabkovo-Nagymaros Dam Case, ICJ Reports

(1997) 7 . . . 2, l3, l6, 2l, 23, 28, 30, l07, 109, 110,

112, 113, 117, 124, 126, 127, 131, 139, 139, 163,

170, 173, 179, 181, 207, 213, 214, 216, 226, 227,

238, 233, 237, 279, 302, 316, 339, 342, 344, 346,

349, 331, 331, 338, 361, 362, 363, 699, 764

Gateshead Metropolitan Council v. Secretary of

State for the Environment (1993) JPL 432 . . .

162

Gatina, Gatin, Konyushkova Kazakhstan,

Compliance Committee, UNECE/MP.PP/

C.l/2006/4/Add.l (2006) . . . 294

German Interests in Polish Upper Silesia Case

(1923) PCIJ Sers. A, Nos. 6 and 7 (1926) . . .

237

Great Belt Case See Passage Trough the Great

Belt Case

Greenpeace v. Stone 748 F. Supp. 749 (1990) . . .

168

Guerra v. Italy, 26 EHRR (1998) 337 . . . 283, 284,

296

Gulf of Maine Case, ICJ Reports (1984) 246 . . .

343, 710, 716

Gut Dam Arbitration, 8ILM (1968) 118 . . . 333,

377

Handelskwekerij Bier v. Mines de Potasse

dAlsace, ECJ No 21/76, II ECR (1976)1733;

(1979) Nederlandse Jurisprudentie, No. 113; 11

NYIL (1980) 326; UNYIL (1984) 471; 19 NYIL,

(I988) 496 . . . 312, 314, 313

Hatton v. UK [2003] ECHR (Grand Chamber)

. . . 126, 180, 287, 299

Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Ontario v. US

Environmental Protection Agency 912 F.2d

1323 (1990) . . . 307

Hesperides Hotels Ltd. v. Mufizade [1979] AC

308 . . . 308

Hunt v. Washington State Apple Advertising, 432

US 333 (1977) . . . 783

ICAO Council Case, ICJ Reports (1972) 46 . . .

238

Icelandic Fisheries Cases (UK & Germany v.

Iceland) ICJ Reports (1974) 3 & 173 . . . 173,

179, 181, 193, 196, 200, 201, 202, 204, 232, 418,

343, 369, 709, 710, 713, 777

Ilmari Lansman et al v. Finland (1996) ICCPR

No. 311/1992 . . . 286, 288, 293

Import, Distribution, and Sale of Alcoholic

Drinks by Canadian Provincial Marketing

Agencies, GATT BISD (33th Supp.) 37 (1989)

(Canada BeerI) . . . 799

Import, Distribution, and Sale of Alcoholic

Drinks by Canadian Provincial Marketing

Agencies, GATT BISD (39th Supp.) 27 (1993)

(Canada Beer II) . . . 799, 800

Import Prohibition of Certain Shrimp and

Shrimp Products, WTO Appellate Body (1998)

WT/DS38/AB/R; 38 ILM (1999) 118 (Shrimp/

Turtle Case) . . . 20, 21, 22, 93, 108, 109, 111,

117, 127, 234, 237, 262, 742, 733, 763, 764, 763,

766, 767, 768, 769, 772, 773, 773, 776, 789, 793

Indian Council for Environmental

Action v. Union of India (1996) 3 SCC

212 . . . 298

In re Oil Spill by Amoco Cadiz 934 F.2d 1279

(1992) . . . 312

Interpretation of the Peace Treaties Case, ICJ

Reports (1930) 63 . . . 237

Intertanko Case (2007) ECJ C-308/06 . . . 440

Iron Rhine Case, PCA (2003) . . . 2, 6, 16, 19, 21,

108, 109, 112, 116, 117, 119, 127, 237

Italian Discrimination Against Imported

Machinery, GATT BISD (7th Supp.) 60 (1939)

. . . 738

Jacobsson v. Sweden (No.2) (1998-I) ECHR . . .

287

Jan Moyen Case, ICJ Reports (1993) 38 . . . 190,

710, 716

Jan Moyen Conciliation, 20 ILM (1981) 797 . . .

263

Japan Measures Afecting the Import of Apples,

WT/DS243/AJ3/R (2003) . . . 142, 174

Japan Shochu Case See Taxes on Alcoholic

Beverages

xxii table of cases

Japanese Whaling Association v. American

Cetacean Society, 478 US 221 (1986) . . . 298

Jagannath v. Union of India (1997) 2 SCC 87 . . .

276, 283, 298

Kalkar Case (1979) 49 Entscheidungen des

Bundesverfassungsgerichts 89 . . . 162

KasilikilSedudu Island Case (Botswana/

Namibia) ICJ Reports (1999) 1033 . . . 19

Katsoulis and ors v. Greece (2004) ECHR . . .

287

Katte Klitsche and de la Grange v. Italy (1994)

ECHR Sers. A/293B . . . 28

Ketua Pengarah Jabatan Sekitar & Anor v.

Kajing Tubek & Ors. [1997] 3 MLJ 23 . . . 297

Kichwa Peoples of the Sarayaku community and

its members v Ecuador, Case 167/03, Report

No. 62/04, Inter-Am CHR, OEA/Ser.L/V/

II.l22 Doc. 3 rev 1 at 308 (2004) . . . 286

Kingdom of Spain v. American Bureau of

Shipping, US Dist. Ct, SD New York (2008)

. . . 439

Kyrtatos v. Greece [2003] ECHR 242 . . . 273,

283, 301

La Bretagne Arbitration (Canada/France) (1986)

82ILR 391 . . . 20

Lac Lanoux Arbitration, 24 ILR (1937) 101 . . .

38, 144, 176179, 194, 204, 226, 478, 313, 342,

343, 330, 333, 333, 367, 368, 369, 370

Land, Island and Maritime Frontier Case

(Nicaragua Intervention) ICJ Reports (1990)

92 . . . 233

Land Reclamation Arbitration, PCA (2003) . . .

108, 227

Land Reclamation by Singapore in and around

the Straits ofJohor (Provisional Measures)

Case [Land Reclamation Case] (2003) ITLOS

No. 12 . . . 108, 140, 138, 168, 170, 172, 173,

179, 226227, 388, 462

LandSarre v. Minister for Industry, Posts and

Telecommunications, ECJ Case 187/87 (1988)

1 CMLR (1989) 329 . . . 306

Landelijke Vereniging tot Behoud van de

Waddenzee, Nederlandse Vereniging tot

Bescherming van Vogels v. Staatssecretaris van

Landbouw, Natuurbeheer en Visserij (2004)

ECR (Waddenzee Case) . . . 163

LCB v. United Kingdom, 27 EHRR (1999) 212

. . . 121

Leatch v. National Parks and Wildlife Service

(1993) 81 LGERA 270 . . . 162

Libya-Malta Continental Shelf Case, ICJ Reports

(1983) 13 . . . 22, 23, 418, 470, 343, 713

Lopez Ostra v. Spain (1994) 20 EHRR 277 . . .

283, 284

Lotus Case, PCIJ Ser. A, No. 10 (1927) . . . 23,

332, 401, 422, 470, 478

Loizidou v. Turkey (Preliminary Objections)

(1993) ECHR, Sers. A/310; (Merits) (l996 - VI)

ECHR . . . 299

Lubbe v. Cape plc [2000] 1 WLR 1343 . . . 306,

309, 310

Lujan v. Defenders of Wildlife 304 US 333 (1992)

. . . 297

Matos eSilva Lda v. Portugal (1996-IV) ECHR; 3

Int.Env.LR (2001) . . . 287

Marsh v. Oregon Natural Resources Council, 490

US 360 (1989) . . . 174

Maya indigenous community of the Toledo

District v. Belize, Inter-Am CHR, OEA/

Ser.L/V/II.122 Doc. 3 rev. 1 (2004) . . . 126,

274, 284, 283, 288 293, 320

Mayagna (Sumo) Awas Tingni Community v

Nicaragua (2001) IACHR Ser. C, No. 20 . . .

274, 273, 284, 286

McGinley andEgan v. U.K. (1998-I) ECHR . . .

296

M.C. Mehta v. Union of India (1987) 1 SCC 393; 1

SCC 471; 4 SCC 463 . . . 297

M.C. Mehta v. Union of India (1997) 2 SCC 333

. . . 139, 276

M.C. Mehta v Kamal Nath (2000) 6 SCC 213 . . .

283

M.V. Saiga (Provisional Measures) ITLOS No. l

(1997); 37 ILM (1998) 360 . . . 400, 401

Measures Afecting Agricultural Products, WTO

Panel (1998) WT/DS76/R . . . 781

Measures Afecting Asbestos and Asbestos-

Containing Products, WTO Panel (2001) WT/

DS133/AB/R; 40 ILM (2001) 1193 (Asbestos

Case) . . . 108, 234, 738, 761, 763, 763, 766,

773, 774

Measures Afecting the Import of Salmon, WTO

Appellate Body (1998) WT/DS18/AB/R . . .

7818

Measures Concerning Meat and Meat Products,

WTO Appellate Body (1997) WT/DS26/AB/R

(Beef Hormones Case) . . . 28, 108, 109, 133,

136, 138, 160, 174, 781, 782, 783

Merlin v. BNFL [1990] 2 QB 337 . . . 324

Metalclad Corporation v. United Mexican States,

ICSID No. ARB(AF)/97/1 (2000) . . . 326, 327

Methanex Corporation v. United States of

America, UNCITRAL Final Award (2003) . . .

111, 326

Metropolitan Nature Reserve v. Panama,

Inter-Am. C.H.R., OEA/Ser.L/V/II.118 Doc.

7O rev 2, 324 (2003) . . . 301

table of cases xxiii

Michie v. Great Lakes Steel Division, 493 F. 2d.

213 (1974) . . . 324

Minors Oposa v. Secretary of the Department of

Environment and Natural Resources, 33 ILM

(1994) 173 . . . 122, 297, 298

Missouri v. Illinois, 200 US 496 (1906) . . .

333

MOX Plant Arbitration (Jurisdiction and

Provisional Measures) PCA (2OO3) . . . 20,

140, 214, 232, 239

MOX Plant Case (Provisional Measures) ITLOS

No. 10 (2001) . . . 140, 149, 136, 138, 168,

170171, 173, 181, 204, 214, 226, 260, 298, 388,

462

Mullin v. Union Territory of Delhi, AIR 1981 SC

746 . . . 283

Namibia Advisory Opinion, ICJ Reports (1971)

16 . . . 20, 233, 238

National Organization for the Reform of

Marijuana Laws v. US Dept. of State 432 F.

Supp. 1226 (1978) . . . 168

Natural Resources Defense Council Inc. v.

Nuclear Regulatory Commission 647 F.2d

1343 (1981) . . . 168

NEPA Coalition of Japan v. Aspin 837 F. Supp.

466 (1993) . . . 168

New York v. New Jersey, 236 US 296 (1921) . . .

333

Nicaragua Case see Paramilitary Activities in

Nicaragua Case

Nicholls v. DG of National Parks and Wildlife

(1994) 84 LGERA 397 . . . 162

North Dakota v. Minnesota, 263 US 363 (1923)

. . . 333

North Sea Continental Shelf Case, ICJ Reports

(1969) 3 . . . 16, 22, 24, 30 31, 179, 181, 322,

470, 343, 369

Norwegian Fisheries Case, ICJ Reports (1931) 116

. . . 190, 776, 777

Nottebohm Case, ICJ Reports (1933) 4 . . . 23, 236

Nuclear Tests Cases (Australia v. France)

(Interim Measures) ICJ Reports (1973) 99;

(Jurisdiction) ICJ Reports (1974) 233 . . . 107,

131, 144, 177, 201, 228, 233234, 490, 309, 311,

313, 318

Nuclear Tests Cases (New Zealand v. France)

(Interim Measures) ICJ Reports (1973) 133;

(Jurisdiction) ICJ Reports (1974) 437 . . . 131,

138, 201, 228, 233234, 490 309, 311, 313, 318

Nuclear Tests Case (New Zealand v. France)

ICJ Reports (1993) 288 see Request for an

Examination of the Situation etc.

Nuclear Weapons Advisory Opinions, ICJ

Reports (1996) 66 (WHO) and 226

(UNGA) . . . 1, 31, 39, 109, 112, 120, 1389,

143, 169170, 184, 183, 206, 207, 213, 233, 234,

491, 310

calan v. Turkey (2003) 37 EHRR 10 . . . 273

Ogoniland Case: see Social and Economic Rights

Action Center and the Center for Economic

and Social Rights v. Nigeria

Ohio v. Wyandotte Chemicals Corp. 401 US 493

(1971) . . . 313

Oil Platforms Case (Jurisdiction), ICJ Reports

(1996) 803 . . . 237

Oil Platforms Case (Merits), ICJ Reports (2003)

161 . . . 20, 21, 109

Ominayak and Lubicon Lake Band v. Canada

(1990) ICCPR Comm. No. 167/1984 . . . 273, 288

neryildiz v. Turkey [2004] ECHR 637 . . . 283,

284, 287, 296

Organizin Indigena deAnioquia v. Codechoco

andMadarien (1993) ECOSOC, UN Doc E/

CN.4/Sub.2/1993/7, 16 . . . 297

OSPAR Convention Arbitration, PCA (2003) . . .

21, 22, 232, 237, 291

Owusu v. Jackson (2003) ECJ C-281/02 . . . 310

Paramilitary Activities in Nicaragua Case

(Merits), ICJ Reports (1986) 14 . . . 23, 24, 33,

206, 236, 414, 310

Passage Trough the Great Belt Case, ICJ Reports

(1991) 12 and (1992) 348 . . . 138

Patmos Case, IOPC Fund, Annual Report (1990)

27 . . . 437

Pakootas v. Teck Cominco Metals Ltd [2004] US

Dist Lexis 23041 (ED Wash) [Trail Smelter

II] . . . 311, 313, 378

Passage Trough the Great Belt Case [Great

Belt Case], ICJ Reports (1991) 12 and ibid,

(1992)348 . . . 138

People of Saipan v. US Dept. of Interior 336 F.

Supp. 643 (1973) . . . 168

People United for Better Living in Calcutta v.

West Bengal AIR 1993 Cal 213 . . . 298

Prineas v. Forestry Commission of New South

Wales (1983) 49 LGRA 402 . . . 174

Pfzer Inc. v. Govt. of India 434 US 308 (1978)

. . . 307

Pfzer Animal Health v. Council of the EU (2002)

II ECR 3303 . . . 136, 137, 161, 164

Phosphate Lands in Nauru, ICJ Reports (1993)

322 . . . 121, 138

Pike v. Bruce Church Inc., 397 US 137 (1970) . . . 783

Pine Valley Developments Ltd. v. Ireland (1991)

ECHR Sers. A/222; 3 Int.Env.LR (2001) . . .

287

xxiv table of cases

Piper Aircraf Co. v. Reyno 434 US 233 (1981)

. . . 309

Port Hope Environmental Group v. Canada,

ICCPR No. 67/1980, 2 Selected Decisions of the

UNHRC (1990) 20 . . . 283

Pulp Mills on the River Uruguay Case

(Provisional Measures)(Argentina v Uruguay)

ICJ Reports (2006) . . . 81, 111, 116, 118, 119,

127, 139140, 148149, 138139, 169171, 173,

174, 176177, 179, 181, 182, 214, 226227, 243,

234, 238, 261, 308, 430, 361, 363

Queensland v. the Commonwealth of Australia

(1989) 167 CLR 232 . . . 298

R v. Secretary of State for the Environment ex

parte Rose Teatre Trust Ltd. [1991] 1 QB 304

. . . 294

R v. Secretary of State for Foreign and

Commonwealth Afairs, ex parte World

Development Movement [1993] 1 All ER 611

. . . 294

R v. Secretary of State for Trade and Industry ex

parte Duddridge (1996) 2 CMLR 361 . . . 162

R v Secretary of State ex parte Greenpeace [1994]

4 All ER 332 . . . 294

R. (ex parte Greenpeace Ltd) v Secretary of State

for Trade and Industry [2007] EWHC 311

Reparation for Injuries Sufered in the Service of

the United Nations Case, ICJ Reports (1949)

174 . . . 46, 38

Request for an Examination of the Situation in

Accordance with the Courts Judgment in the

Nuclear Tests Case (New Zealand v. France)

[Nuclear Tests Case], ICJ Reports (1993) 288

. . . 112, 138, 169

Reservations to the Genocide Convention Case,

ICJ Reports (1931) 13 . . . 18

Restrictions on Imports of Tuna, GATT, 30 ILM

(1991) 1398 [Tuna/Dolphin I Case] . . . 734,

763, 767, 768, 769, 770, 772, 773, 774, 776, 777,

778, 786, 791, 810

Restrictions on Imports of Tuna, GATT, 33 ILM

(1994) 839 [Tuna/Dolphin II Case] . . . 734,

763, 770, 771, 772, 773, 774, 776, 777, 778, 789,

793, 810

Rewe-Zentral AG v. Bundesmonopolverwaltung

fur Branntwein [Cassis de Dijon Case] ECJ

Case 120/78 [1979] ECR 649 . . . 783

Rhine Chlorides Convention Arbitral Award

(FrancelNetherlands) PCA (2004) . . . 322

Richardson v. Tasmanian Forestry Commission

(1988) 77 ALR 237 . . . 298

River Oder Case See Territorial Jurisdiction

of the International Commission of the River

Oder Case

Robertson v. Methow Valley Citizens Council,

490 US 332 (1989) . . . 174

Rural Litigation and Entitlement Rendra v. State

of Uttar Pradesh, AIR 1983 SC 632; AIR 1987

SC 339; AIR 1988 SC 2187 . . . 283, 297, 298

Rylands v. Fletcher (1868) LR 3 HL 330 . . . 219

S.S. Wimbledon Case, PCIJ Ser. A, No. 1 (1923)

. . . 234

Saugbruksforeningen Case, Norsk Retstidende

(1992) 1618 . . . 307

SD Myers Inc v Canada, UNCITRAL (2000) . . .

326

Section 337 of the Tarif Act of 1930, GATT

B.I.S.D. (36th Supp.) 343 (1990) . . . 758

Shela lia v. WAPDA (1994) SC 693 (Pakistan) . . .

139, 297

Shevill v. Presse Alliance SA [1993] 2 WLR 499

. . . 314

Shrimp Turtle Case see Import Prohibition of

Certain Shrimp and Shrimp Products

Sierra Club v. Morton, 403 US 727 (1972) . . . 297

Silkwood v. Kerr McGee Corp., 464 US 238 (1984)

. . . 323

Social and Economic Rights Action Center and

the Center for Economic and Social Rights

v. Nigeria, ACHPR Comm. 133/96 (2002)

[SERAC v. Nigeria] . . . 126, 273, 277, 286,

289, 293, 320, 327

Soering v. UK (1989) 11 EHRR 439 . . . 273

Sosa v. Alvarez-Machain 124 S.Ct. 2739 (2004)

. . . 327

Soucheray et al. v. US Corps of Engineers, 483 F

Supp. 332 (1979) . . . 306

South West Africa Cases, ICJ Reports (1930) 128;

ICJ Reports (1962) 319: ICJ Reports (1966) 9

. . . 21, 27, 220, 232, 241, 321

South West Africa (Voting Procedure) Case, ICJ

Reports (1933) 67 . . . 241

Southern Bluefn Tuna Cases (Provisional

Measures) (l999) ITLOS Nos. 3&4 . . . 108,

138, 160, 163, 172, 176, 199, 204, 226, 227, 260,

388

Southern Bluefn Tuna Arbitration, 39 ILM

(2000) 1339 . . . 232, 239

Sovereignty over Pulau Ligitan and Pulau

Sipadan (Indonesia/Malaysia) ICJ Reports

(2002) 623 . . . 19

Spiliada Maritime Corp. v. CansulexLtd. [1987]

AC 460 . . . 309

Sporrong and Lonnroth v. Sweden, EHCR Sers.

A/32 (1982) . . . 287, 320

Standards for Reformulated and Conventional

Gasoline, WTO Appellate Body (1996) WT/

DS2/AB/R; 33 ILM (1996) 274 (US

table of cases xxv

Gasoline Standards case) . . . 760, 76l, 763,

766, 772, 773

Stichting Greenpeace Council v. EC Commission

(1998) I-ECR 1631; 3 CMLR (1998) 1 . . . 297

Subhash Kumar v. State of Bihar, AIR 1991 SC

420 . . . 283

Svidranova v. Slovak Republic, ECHR App.No.

33268/97 (1998); 3 Int.Env.LR (2001) . . . 287

Swordfsh Case (Chile v. EC) JTLOS No. 7 (2001);

40 ILM (2001) 473 . . . 261, 766

Syndicat Professionel etc v. EDF (2004) ECJ Case

C-213/03 . . . 298

T. DamodharRao v. Municipal Corporation of

Hyderbad, AIR 1987 AP 171 . . . 283, 297, 298

Taskin v. Turkey [2006] 42 EHRR 30 . . . 173,

283, 284, 283, 287, 288, 290, 293, 293

Taxes on Petroleum and Certain Imported

Substances, GATT BISD (34th Supp.) 136

(1988) [US Superfund case] . . . 797, 799, 800

Taxes on Alcoholic Beverages, WTO Appellate

Body, WTO Doc. AB-19962 (1996) [Japan

Shochu case] . . . 738, 771, 798, 799

Tehran Hostages Case, ICJ Reports (1980) 29 . . .

148, 214, 316, 363

Territorial Dispute (Libyan Arab Jamahiriya/

Chad) ICJ Reports (1994) 6 . . . 14

Territorial Jurisdiction of the International

Commission of the River Oder Case [River

Oder Case], PCIJ Ser. A, No. 23 (1929) . . . 342

Texaco v. Libya, 33 ILR (1977) 389 . . . 32, 191

Tomas v. New York, 802 F. 2d. 1443 (1986) . . .

303

Trade in Semi-Conductors, GATT B.I.S.D. (33th

Supp.) 113 (1989) . . . 739

Trail Smelter Arbitration, 33 AJIL (1939) 182 &

33 AJIL (1941) 684 . . . 27, 38, 107, 111, 142,

143, 143, 146147, 133, 134, 173, 180181, 184,

186, 211, 216, 217, 218, 226228, 230, 263, 308,

319, 344, 332, 330, 331, 333, 377

Tuna/Dolphin Cases See Restrictions on Import

of Tuna

Tunisia-Libya Continental Shelf Case, ICJ

Reports (1982) 18 . . . 343

In re Union Carbide Corporation Gas Plant

Disaster at Bhopal 634 F.Supp.842 (1986; 809

F.2d 193 (1987) [hopal Case] . . . 298, 309,

310, 312, 313

Unprocessed Salmon and Herring case, GATT

B.I.S.D. (33th Supp.) 98 (1989) [Canada

Herring Case]

United Kingdom v. EC Commission (1998) IECR

2263 . . . 162

US Gasoline Standards Case See Standards for

Reformulated and Conventional Gasoline

United States Shrimp, Recourse to Art 21.5 of

the DSU by Malaysia, WTO Appellate Body

(2001) WT/DS38/AB/RW . . . 767

United States Measures Afecting the Cross-

Border Supply of Gambling and Betting

Services, WTO Appellate Body (2003)

WT/DS283/AB/R . . . 774

Vellore Citizens Welfare Forum v. Union of India

(1996) 7 SCC 373 . . . 139, 222, 298

Ville de Tarbes Case, Conseil dEtat, Decision of

26 April 1983 . . . 297

Voth v. Manildra Flour Mills (1990) 171 CLR 338

. . . 310

Te Wagonmound (No.2) [1967] 1 AC 67 . . . 219

Western Sahara Advisory Opinion, ICJ Reports

(1973) 12 . . . 234

Wilderness Society v. Morton, 463 F. 2d. 1261

(1972) . . . 168

World Wildlife Fund Geneva v. France (1997)

Cahiers Juridique de lElectricit et Gaz 217

. . . 162

YakyeAxa imligenous community of the Enxet-

Lengua people v. Paraguay, Case 12.313,

Report No. 2/02, Inter-Am CHR, Doc. 3 rev 1,

387 (2002) . . . 286

Yanomani Indians v. Brazil, Decision 7613,

Inter-Am CHR, Inter-American YB on Hum.

Rts. (1983)264 . . . 274, 283

Yemen-Eritrea Maritime Boundary Arbitration,

40 ILM (2001) 983 . . . 710

This page intentionally left blank

1.nii oi m.,ov 1vi.1iis

.u is1vUmi1s

Only those treaties and other instruments which are cited frequently in the text or

are of particular signifcance are listed here. References to other treaties will be found

in the footnotes. Not in force indicates that the treaty had not come into force by 31

December 2007. Most of the major agreements can be found in Birnie and Boyle, Basic

Documents on International Law and the Environment (Oxford, 1993)[hereafer B&B

Docs]. Almost all of these treaties and other instruments are readily accessible on the

internet via a Google search.

1909 Treaty between the United States and Great Britain Respecting Boundary Waters Between

the United States and Canada (Washington) 4AJIL (Suppl.) 239. In force 3 May 1910 . . . 263,

340, 343, 348, 333, 334, 367, 376, 377, 378

1940 Convention on Nature Protection and Wild-Life Preservation in the Western Hemisphere

(Washington) 161 UNTS 193. In force 1 May 1942 . . . 399, 632, 634, 667, 696

1944 United StatesMexico Treaty Relating to the Utilization of Waters of the Colorado and

Tijuana Rivers and of the Rio Grande, 3 UNTS 313. In force 8 November 1943 . . . 348, 370

1945 Charter of the United Nations (San Francisco) 1 UNTS xvi; UKTS 67 (1946) Cmd. 7013; 39

AJIL Suppl. (1943) 190. In force 24 October 1943 . . . 32, 33, 44, 39, 62, 63, 119, 203, 211, 230,

328

1946 International Convention for the Regulation of Whaling (Washington) 161 UNTS 72; UKTS

5 (1949) Cmd. 7604; B&B Docs, 386. In force 10 November 1948. Amended 1936, 338 UNTS

366. In force 4 May 1939 . . . 18, 83, 87, 90, 120, 243, 244, 600, 634, 637, 663,697, 724, 723

1948 Convention on the International Maritime Organization (Geneva) 289 UNTS 48; UKTS 34

(1930) Cmnd. 389; 33 AJIL (1948) 316. In force 17 March 1938 . . . 73, 76, 496,

Universal Declaration of Human Rights, UNGA Res 217A (III) . . . 33, 604

1950 International Convention for the Protection of Birds (Paris) 638 UNTS 183. In force 17

January 1963 . . . 633

European Convention for the Protection of Human Rights and Freedoms (Rome) 213 UNTS

221; UKTS 71 (1933) Cmd. 8969. In force 3 September 1933. Amended by Protocol No. 11, in

force 1 November 1998 . . . 247, 282, 299, 306

1954 International Convention for the Prevention of Pollution of the Sea by Oil (London) 327

UNTS 3; UKTS 34 (1938) Cmnd. 393; 12 UST 2989, TIAS 4900. In force 26 July 1938.

Amended 1962 and 1969 . . . 386, 387, 403, 404

1956 Statute of the International Atomic Energy Agency (New York) 276 UNTS 3; UKTS 19 (1938)

Cmnd. 430; 8 UST 1043, TIAS 3873. In force 29 July 1937 . . . 77, 78, 489, 493499, 303

1957 Interim Convention on Conservation of North Pacifc Fur Seals (Washington) 314 UNTS 103;

8 UST 2283, TIAS 3948. In force 14 October 1937 . . . 663, 712

Treaty Establishing the European Atomic Energy Community (Euratom) (Rome) 298 UNTS

167, UKTS 13 (1979) Cmnd. 7480. In force 1 January 1938 . . . 490, 303307

1958 Convention on Fishing and Conservation of the Living Resources of the High Seas (Geneva)

339 UNTS 283; UKTS 39 (1966) Cmnd. 3028; 17 UST 138, TIAS 3669. In force 20 March 1966

. . . 74, 193, 196, 199, 338, 386, 389, 390, 709, 718, 720, 742

Convention on the Continental Shelf (Geneva) 13 UST 471, TIAS 3378; 499 UNTS 311; UKTS

39 (1964) Cmnd. 2422. In force 10 June 1964 . . . 191, 382, 386, 776

Convention on the High Seas (Geneva) 430 UNTS 82; UKTS 3 (1963) Cmnd. 1929; 13 UST

2312, TIAS 3200. In force 30 September 1962 . . . 193, 201, 382, 386, 403, 422, 438, 636

xxviii table of major treaties and instruments

Convention on the Territorial Sea and Contiguous Zone (Geneva) 316 UNTS 203; 13 UST

1606, TIAS 3639; UKTS 3 (1963) Cmnd. 2311. In force 10 September 1964 . . . 382, 386, 413,

417, 479

1959 Antarctic Treaty (Washington) 402 UNTS 71; UKTS 97 (1961) Cmnd. 1333; 12 UST 794, TIAS

4780. In force 23 June 1961. 1991 Protocol (q.v.) . . . 243, 280, 468, 309

1960 Convention on Tird Party Liability in the Field of Nuclear Energy (Paris) 8 EYB 203; UKTS

69 (1968) Cmnd. 3733; 33 AJIL (1961) 1082. In force 1 April 1968. Amended 1964, UKTS 69

(1968) Cmnd. 3733, in force 1 April 1968; 1982, UKTS 6 (1989) Cm. 389, in force 7 October

1988. Amended by 2004 Protocol, not in force . . . 324, 323, 320, 321, 322, 323, 323, 326, 327,

328, 330, 331, 332

1962 Convention on the Liability of Operators of Nuclear Ships (Brussels) 37 AJIL (1963) 268. Not

in force . . . 314, 312, 321, 322, 323, 323, 326, 327, 331, 332

1963 Agreement Supplementary to the Paris Convention of 1960 on Tird Party Liability in

the Field of Nuclear (Brussels) UKTS 44 (1973) Cmnd. 3948; 2 ILM (1963) 683. In force 4

December 1974. Amended 1964 UKTS 44 (1973) Cmnd. 3948, in force 4 December 1974;

1982, UKTS 23 (1983) Cmnd. 9032, in force 1 August 1991. Amended by 2004 Protocol, not in

force . . . 322, 327, 328

Convention on Civil Liability for Nuclear Damage (Vienna) Misc. 9 (1964) Cmnd. 2333; 2

ILM (1963) 727. In force 12 November 1977. Amended by 1997 Protocol (q.v.) . . . 321, 322,

323, 323, 331, 333

Treaty Banning Nuclear Weapon Tests in the Atmosphere, in Outer Space and Under Water

(Moscow) 480 UNTS 3 (1964) Cmnd. 2243; 14 UST 1313, TIAS 3433. In force 10 October 1963

. . . 490, 310

1964 Convention for the International Council for the Exploration of the Sea (Copenhagen). UKTS

67 (1968) Cmnd. 3722. In force 22 July 1968 . . . 99

1966 International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, 6 ILM (1967) 368. In force 23 March

1976 . . . 113, 272, 281, 282, 283, 288, 290, 299, 306, 309

International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, 6 ILM (1967) 360. In force

3 January 1976 . . . 118, 272, 276, 278

1967 Treaty on Principles Governing the Activities of States in the Exploration and Use of Outer

Space, Including the Moon and other Celestial Bodies, 610 UNTS 203; UKTS 10 (19680,

Cmnd 18 UST 2410, TIAS 6347; 6 ILM (1967) 386. In force 10 October 1967 . . . 136, 143

Treaty for the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons in Latin America (Tlatelolco) 22 UST 762,

TIAS 7137; 6 ILM (1967) 321. In force 22 April 1968 . . . 491, 310

1968 African Convention on the Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources (Algiers) 1001

UNTS 4. In force 16 June 1969. Revised Convention of 2003 (q.v.) . . . 120, 192, 273, 274, 277,

286, 367, 632, 634, 636, 637, 661, 663, 666, 667, 696

1969 Convention on the Law of Treaties (Vienna) 8 ILM (1969) 689. In force 27 January 1980 . . .

16, 18, 19, 20, 21, 28, 30, 36, 207, 233, 238, 237, 327, 339, 764, 763

International Convention on Civil Liability for Oil Pollution Damage (Brussels) 973 UNTS

3; UKTS 106 (1973) Cmnd. 6183; 9 ILM (1970) 43. In force 19 June 1973. 1976 Protocol, UKTS

26 (1981) Cmnd. 8238; 16 ILM (1977) 617. In force 8 April 1981. Replaced by 1992 Convention

(q.v.) . . . 313, 434, 433, 436, 437, 438, 322, 326

International Convention Relating to Intervention on the High Seas in Cases of Oil Pollution

Damage (Brussels) UKTS 77 (1971) Cmnd. 6036; 9 ILM (1970) 23. In force 6 May 1973.

1973 Protocol UKTS 27 (1983) Cmnd. 8924; 68 AJIL (1974) 377. In force 30 March 1983 . . .

426429

1971 Convention on Wetlands of International Importance (Ramsar) 996 UNTS 243 UKTS 34

(1976) Cmnd. 6463; 11 ILM (1972) 963. In force 21 December 1973. Amended 1982 and 1987,

repr. in B&B Docs, 447, in force 1 May 1994 . . . 81, 361, 637, 632, 636, 637, 639, 664, 666, 669,

671, 672, 673, 674, 673, 677, 678, 679, 680, 683, 697

Convention Relating to Civil Liability in the Field of Maritime Carriage of Nuclear Material

(Brussels) Misc. 39 (1972) Cmnd. 3094. In force 13 July 1973 . . . 317, 321

Convention on the Establishment of an International Fund for Compensation for Oil

Pollution Damage (Brussels) UKTS 93 (1978) Cmnd. 7383; 11 ILM (1972) 284. In force 16

October 1978. Replaced by 1992 Convention (q.v.) . . . 434, 433, 436, 438, 440

table of major treaties and instruments xxix

1972 Declaration of the United Nations Conference on the Human Environment (Stockholm) UN

Doc.A/CONF/48/14/REV.l; B&Bdocs, 1 . . . 3, 7, 14, 26, 33, 37, 43, 48, 49, 60, 63, 73, 110, 117,

120, 128, 144, 143, 176, 188, 189, 221, 271, 274, 277, 303, 329, 339, 341, 382, 403, 466, 491

UNESCO Convention Concerning the Protection of the World Cultural and Natural

Heritage, UKTS 2 (1983) CMND. 9424; 27 UST 37, TIAS 8223; 11 ILM (1972) 1338; B&B Docs,

373. In force 17 December 1973 . . . 36, 60, 81, 90, 91, 192, 200, 234, 280, 612, 614, 632, 637,

638, 664, 666,669, 670, 671,672, 673, 676, 677, 679, 680, 694, 697, 698

Convention on the Prevention of Marine Pollution by Dumping of Wastes and other Matter

(London) 26 UST 2403, TIAS 8163; UKTS 43 (1976) Cmnd. 6486; 11 ILM (1972) 1294; B&B

Docs, 174. In force 30 August 1973. Replaced by 1996 Protocol (q.v.) . . . 13, 143, 240, 238, 239,

330, 387, 389, 392, 394, 414, 413, 416, 417, 467, 468, 469, 470, 471 ,472

Convention on International Liability for Damage Caused by Space Objects, 961 UNTS 187;

UKTS 16 (1974) Cmnd. 3331; 24 UST 2389, TIAS 7762. In force 1 September 1972 . . . 218, 229,

317, 318, 322, 324

Convention for the Conservation of Antarctic Seals (London) 29 UST 441, TIAS 8826; 11 ILM

231. In force 11 March 1978 . . . 727

Convention on the International Regulations for Preventing Collisions at Sea, UKTS 68

(1984) Cmnd. 9340, in force 1 June 1983 . . . 401

1973 Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora

(Washington) 993 UNTS 243; UKTS 101 (1976) Cmnd. 6647; 12 ILM 1083 (1973); B&B Docs,

413. In force 1 July 1973 . . . 18, 20, 70, 81, 83, 90, 91, 92, 93, 94, 192, 200, 234, 240, 243, 246,

238, 280, 330, 482, 484, 399, 614, 649, 632, 637, 638, 661, 664, 663, 670, 671, 672, 678, 679, 684,

683, 686, 687, 688, 689, 690, 691, 697, 698, 699, 700, 734, 734, 764, 766, 767

International Convention for the Prevention of Pollution by Ships (MARPOL) (London)

UKTS 27 (1983) Cmnd. 8924; 12 ILM (1973) 1319. Amended by Protocol of 1978 (q.v.) before

entry into force . . . 76, 83, 146, 130, 207, 240, 243, 238, 239, 330, 381, 382, 387, 389, 400,

401413, 414, 417, 418, 419, 420, 422, 428, 434, 440, 441, 446, 477, 479, 480, 481, 302

Agreement on the Conservation of Polar Bears (Oslo) 27 UST 3918, TIAS 8409; ILM 13 (1974)

13. in force 26 May 1976 . . . 632, 633

1974 Nordic Convention on the Protection of the Environment (Stockholm) 13 ILM (1974) 311. In

force 3 October 1976 . . . 132, 263, 303, 307, 366

Convention on the Protection of Marine Environment of the Baltic Sea Area (Helsinki) 13

ILM (1974) 346. In force 3 May 1980. Replaced by 1992 Helsinki Conventior (q.v.) . . . 87, 393,

423, 432

Convention for the Prevention of Marine Pollution from Land-Based Sources (Paris) UKTS

64 (1978) Cmnd. 7231; 13 ILM (1974) 332. In force 6 May 1978. Amended by Protocol of

1986,27 ILM (1988) 623, in force 1 February 1990. Replaced by 1992 Paris Convention (q.v.)

. . . 87, 188, 344, 394, 372

International Convention for the Safety of Life at Sea, 1184 UNTS 2; UKTS 46 (1980) . . . 76,

401, 403, 406, 411, 414, 413, 416, 419, 429, 441, 308, 312, 3l3 Cmnd. 7874 TIAS 9700. In force

23 May 1980, as subsequently amended

1976 Convention for the Protection of the Mediterranean Sea Against Pollution (Barcelona);

Protocol Concerning Cooperation in Combating Pollution of the Mediterranean Sea by

Oil and Other Harmful Substances in Cases of Emergency; Protocol for the Prevention of

Pollution of the Mediterranean Sea by Dumping from Ships and Aircraf, 13 ILM (1976) 290.

All in force

12 February 1978. 1980 and 1982 Protocols (q.v.). Revised convention and protocols 1993/6

(q.v.) . . . 393, 396, 424, 423

Convention on Conservation of Nature in the South Pacifc (Apia) Burhenne, 976: 43. In force

28 June 1980 . . . 632

Convention on the Protection of the Rhine Against Chemical Pollution (Bonn) 1124 UNTS

373; 16 ILM (1977) 242. In force 1 February 1979. Replaced by 1999 Convention (q.v.) . . . 87,

181, 183, 187, 323, 337, 333, 371, 373, 374

Convention for the Protection of the Rhine from Pollution by Chlorides (Bonn) 16 ILM

(1977) 263. In force 3 July 1983. Amended by 1991 Protocol . . . 87, 323, 371, 373

xxx table of major treaties and instruments

Convention on the Prohibition of Military or Any Other Hostile Use of Environmental

Modifcation Techniques (Geneva) 31 UST 333, TIAS 9614; 16 ILM (1977) 88. In force 3

October 1978 . . . 203

1977 Protocols I and II Additional to the Geneva Conventions of 12 August 1949 and Relating to

the Protection of Victims of International Armed Conficts, 1123 UNTS 3; 1123 UNTS 609; 16

ILM (1977) 1391. In force 7 December 1978 . . . 310311

1978 Protocol Relating to the Convention for the Prevention of Pollution from Ships (MARPOL)

17 ILM (1978) 346; B&B Docs, 189. In force 2 October 1983. Annexes I-VI in force. Current

texts in IMO, MARPOL Consolidated Edition . . . 92, 136, 130, 238, 239, 381, 387, 389,

401413, 418, 419, 420, 422, 428, 434, 440, 441, 446, 477, 479, 480, 481, 484, 302

Convention on Future Multilateral Co-operation in the North-West Atlantic Fisheries. Misc.

9 (1979) CMND. 7369. In force 1 January 1979. Amended 1979, Misc. 9 (1980) Cmnd. 7863 . . .

92, 94, 244

Regional Convention for Cooperation on the Protection of the Marine Environment from

Pollution (Kuwait) 1140 UNTS 133; 17 ILM (1978) 311. In force 1 July 1979. Protocols 1978,

1989, 1990 (q.v.) . . . 423, 431, 461

Protocol Concerning Regional Cooperation in Combating Pollution by Oil and Other

Harmful Substances in Cases of Emergency (Kuwait) 17 ILM (19780, 326. In force 1 July 1979

. . . 424, 423, 432

Treaty for Amazonian Cooperation (Brasilia) 17 ILM (1978) 1043. In force 2 February 1980

. . . 337, 344

United States-Canada Agreement on Great Lakes Water Quality with Annexes, 30 UST

1383, TIAS 9237. In force 27 November 1978. Amended 1983; TIAS 10798 . . . 337, 372,

377, 378

UNEP Principles on Conservation and Harmonious Utilization of Natural Resources Shared

by Two or More States, 17 ILM (1978) 1094; B&B Docs, 21 . . . 26, 68, 176, 193

1979 Convention on the Conservation of Migratory Species of Wild Animals (Bonn) 19 ILM

(1980) 13; B&B Docs, 433. In force 1 November 1983 . . . 17, 20, 68, 90, 388, 614, 632, 634, 636,

639, 663, 666, 670, 672, 676, 678, 681, 682, 683, 684, 683, 697, 698, 764

Convention on the Conservation of European Wildlife and Natural Habitats (Berne) UKTS

36 (1982) Cmnd. 8738; ETS 104; B&B Docs, 433. In force 1 June 1982 . . . 90, 280, 399, 614, 633,

639, 663, 667, 683, 696, 697

Convention on Long-Range Transboundary Air Pollution (Geneva) UKTS 37 (1983) Cmd,

9034; TIAS 10541; 18 IILM (1979) 1442; B&B Docs, 277. In force 16 Marci 1983. Protocols of

1984, 1983, 1988, 1991, 1994 and 1998 (q.v.) . . . 17, 72, 73, 81, 91, 144, 181, 187, 247, 333, 339,

343343, 348, 330, 331, 791

Agreement Governing the Activities of States on the Moon and Other Celestial Bodies, 18

ILM (1979) 1434. In force 11 July 1984 . . . 96, 143

Convention for the Conservation and Management of the Vicuna (Lima) Burhenne 979: 94.

In force 19 March 1982 . . . 632, 633

1980 Protocol for the Protection of the Mediterranean Sea against Pollution from Land-Based

Sources (Athens) 19 ILM (1980) 869. In force 17 June 1983. Replaced by 1996 Protocol (q.v.)

. . . 170, 439, 460, 464

Convention on the Conservation of Antarctic Marine Living Resources (Canberra) UKTS 48

(1982) CMND. 8714; TIAS 10240; 19 ILM (1980) 837; BB Docs, 628. In force 7 April 1982 . . .

6, 87, 94, 280, 389, 392, 632, 633, 633, 660

Convention on Future Multilateral Co-operation in North-East Atlantic Fisheries, Misc. 2

(1980) Cmnd. 8474. In force 17 March 1982 . . . 244

1981 African Charter on Human Rights and Peoples Rights (Banjul) 21 ILM (1982) 32 In force 21

October 1986 . . . 273, 278, 279

Convention and Protocol for Cooperation in the Protection and Development of the

Marine and Coastal Environment of the West and Central African (Abidjan) and Protocol

concerning Co-operation in Combating Pollution in Cases of Emergency, 20 ILM (1981) 746.

In force 3 August 1984 . . . 392, 424, 423, 432, 431432, 461, 462

table of major treaties and instruments xxxi

Convention for the Protection of the Marine Environment and Coastal Area of the South-

East Pacifc (Lima) ND (Looseleaf) Doc. J. 18. In force 19 May 1986 . . . 392

Agreement on Regional Cooperation in Combating Pollution of the South-East Pacifc by

Hydrocarbons on Other Harmful Substances in Cases of Emergency (Lima) ND (Looseleaf)

Doc. J. 18. In force 14 July 1986 . . . 392, 424, 423, 432, 461, 462

1982 Regional Convention for the Conservation of the Red Sea and Gulf of Aden Environment

(Jeddah) and Protocol Concerning Regional Co-operation in Combating Pollution by Oil

and Other Harmful Substances in Cases of Emergency, 9 EPL 36 (1982) All in force 20 August

1983 . . . 424, 432, 432, 461

Protocol Concerning Mediterranean Specially Protected Areas (Geneva) ND (Looseleaf)

Doc. J. 20. In force 23 March 1986. Replaced by 1996 Protocol (q.v.) . . . 416

World Charter for Nature, UNGA Res. 37/7, 37 UNGAOR Suppl. (No. 31) at 17, UN Doc.

A/37/31 (1982) . . . 69, 329

Convention for the Conservation of Salmon in the North Atlantic Ocean (Reykjavik) EEC OJ

(1982) No. L378, 23; Misc. 7 (1983) Cmnd. 8830. In force 10 October 1983 . . . 94, 728

UN Convention on the Law of the Sea (Montego Bay) Misc. 11 (1983) Cmnd. 8941; 21 ILM

(1982) 1261. In force 16 November 1994 . . . 3, 6, 13, 13, 17, 18, 20, 23, 39, 46, 74, 76, 83, 89, 94,

93, 97, 107, 111, 128, 133, 136, 141, 144. 143, 149, 132, 160, 163 167168, 170, 173, 176, 182, 183,

183, 193, 197198, 201, 207, 218, 241, 231, 232236, 238, 239, 263, 319, 330, 332, 333, 338, 330,

382442, 431, 433, 434, 433, 461, 462, 463, 466, 468, 469, 470, 471, 479, 480, 481, 486, 487, 493,

301, 302, 312, 316, 343, 331, 334, 337, 389, 391, 393, 634, 637, 638, 661, 662, 668, 696, 704, 703,

709, 711, 712, 713, 714, 713, 716, 717, 718, 719, 720, 721, 722, 723, 724, 727, 729, 730, 732, 733,

734, 733, 736, 737, 739, 741, 742, 743, 743, 746, 748, 730, 731, 764, 777

1983 Convention for the Protection and Development of the Marine Environment of the Wider

Caribbean Region (Cartegena de Indias) and Protocol Concerning Co-operation in

Combating Oil Spills in the Wider Caribbean Region, 22 ILM (1983) 221: UKTS 38 (1988) Cm

399. In force 11 October 1986. (1990 Protocol q.v.) . . . 170, 392, 423, 423, 432, 432, 461, 462

Protocol for the Protection of the South-East Pacifc Against Pollution from Land-Based

Sources (Quito): Burhenne, 983: 33. In force 23 September 1986 . . . 183, 397, 432, 433, 436,

461, 462

1985 Convention for the Protection of the Ozone Layer, (Vienna) UKTS 1 (1990) Cm. 910; 26 ILM

(1987) 1329; B&B Docs 211. In force 22 September 1988 (1988 Protocol q.v.) . . . 6, 8, 13, 16, 17,

18, 39, 68, 83, 88, 90, 91, 107, 111, 136, 144, 146, 137, 183, 186, 188, 234, 333, 341, 349, 330, 669

South Pacifc Nuclear Free Zone Treaty (Raratonga) 24 ILM (1983) 1442. In force 11

December 1986 . . . 491, 310

Convention for the Protection, Management and Development of the Marine and Coastal

Environment of the Eastern African Region (Nairobi); Protocol Concerning Protected Areas

and Wild Flora and Fauna in the Eastern African Region; Protocol Concerning Co-operation

in Combating Marine Pollution in Cases of Emergency in the Eastern African Region,

Burhenne, 383: 46; ND (Looseleaf) Doc. J. 26 In force 30 May 1996 . . . 388, 392, 397, 424, 432,

433, 461, 462

Protocol on the Reduction of Sulphur Emissions, (Helsinki) 27 ILM (1988) 707. In force 2

September 1987 . . . 346

ASEAN Agreement on the Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources (Kuala Lumpur,

13 EPL (1983) 64. Not in force . . . 399, 632, 661, 668, 693, 696

1986 Convention on Early Notifcation of a Nuclear Accident, (Vienna) Misc. 2 (1989) Cm. 363; 23

ILM (1986) 1370; B&B Docs, 300. In force 27 October 1986 . . . 36,314313

Convention on Assistance in the Case of a Nuclear Accident or Radiological Emergency,.

((Vienna) Misc. 3 (1989) Cm.366; 23 ILM (1986) 1377. In force 26 February 1987 . . . 313

Convention for the Protection of the Natural Resources and Environment of the South

Pacifc Region by Dumping; and Protocol Concerning Co-operation in Combating Pollution

Emergencies in the South Pacifc Region, 26 ILM (1987) 38. In force 18 August 1990 . . . 392,

397, 432, 432, 433, 461, 462, 469, 470, 471, 474479, 309

1987 Protocol on Substances that Deplete the Ozone Layer (Montreal) UKTS 19 (1990) Cm. 977; 26

ILM (1987) 1330; B&B Docs, 224. Current amended text in UNEP, Handbook of the Montreal

xxxii table of major treaties and instruments

Protocol. In force 1 January 1989 . . . 107, 132, 134, 149, 137, 246, 340, 331333, 430, 431, 637,

734, 766, 767, 768

1988 Convention on the Regulation of Antarctic Mineral Resource Activities (Wellington) Misc. 6

(1989) Cm. 634; 27 ILM (1988) 868. Not in force.

Protocol (to the 1979 Geneva Convention) Concerning the Control of Emissions of Nitrogen

Oxides or Teir Transboundary Fluxes (Sofa) Misc. 16 (1989) Cm. 883; 27 ILM (1988) 698. In

force 14 February 1991 . . . 347

Protocol to the 1969 American Convention on Human Rights in the Area of Economic,

Social and Cultural Rights (San Salvador) 28 ILM (1989) 136. In force 16 November 1999 . . .

278

1989 Convention on the Control of Transboundary Movements of Hazardous Wastes and Teir

Disposal (Basel), 28 ILM (1989) 637; B&B Docs, 322. In force 24 May 1992 . . . 18, 19, 47, 68,

81, 144, 137, 182, 242, 243, 243, 330, 403,413, 440, 470, 473486, 494, 303, 309, 734, 766

International Convention on Salvage (London) IMO/LEG/CONF.7/27 (1989). In force 14 July

1996 . . . 229, 388, 429, 433

ILO Convention No. 169 Concerning Indigenous and Tribal Peoples in Independent

Countries, 72 ILO Of. Bull. 39 (1989); 28 ILM (1989) 1382. In force 3 September 1991 . . . 272

Protocol for the Conservation and Management of Protected Marine and Coastal Areas of

the South-East Pacifc (Paipa) ND (Looseleaf) Doc. J. 33. In force 17 October 1994 . . . 397

Protocol for the Protection of the South-East Pacifc Against Radioactive Pollution (Paipa)