Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

The Journal of The Siam Society Vol. Liii Part 1-2-1965

Enviado por

pajamsaepTítulo original

Direitos autorais

Formatos disponíveis

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

The Journal of The Siam Society Vol. Liii Part 1-2-1965

Enviado por

pajamsaepDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

VOWME UU PART l

JANUARY

THE

;JOURNAl..

OF THE

' ' '

' .

TB)D SIAM SOOlETY

His Majestytb'el{ing

Ber Maj(!sty the

Her Majesty B11rni

;Her the ,Princess o Songkhla

I,\:ip:g.FrederikJX of Denmark

''I ' ( !.'.:' '. ., . ,, , /"' ,< " ', :' ': '

VOWME LIII PART 1 JANUARY 1965

THE

J URNAL

OF THE

BANGKOK

2508

TABLE OF CONTENTS

VOLU.!VIE LIII PART 1 ,JANUARY :l..IHH'i

Articles

H.G. Quaritch Wales

Professor Gordon H. Luce

John H. Brandt

Thamsook Nurnnonda

H.H. Prince Dhaninivat,

Kromarnun Bidyalabh

Phya Anuman Rajadhon

Larry Sternstein

Book Review

Larry Sternstein

Rece11t Siamese Publications :

Muang Bon, A Tawn of Northern Dvaravati

Dvaravatz and Old Burma

The Southeast Asian Negrito

The Anglo-Siamese Secret Convention of I 8D7

Hide Figures of the Ramakien

Notes : W at Sijum, Sriraja, Lavo

Data on Conditioned Poison

'K.rung K.ao' : The Old CajJital

of Ayutthaya

Text-Book Thailand

D.

318. Attributes of His Holiness Kromsanulecfna Param'iinujit

319. Letters to a friend during the state visit of

their Majesties to America

320.

Their Majesties' Official Visits to Pakistan and Malaya

321. The Story of the Sihala Image

Page

10

27

45

61

67

69

83

123

127

128

129

130

MUANG BON, A TOWN OF NORTHERN DV ARA v ATi

by

'J(.r:J. Qrwritdz, C(Q)alcs

In a previous article in this journal

1

I called attention to the

correct location of Williams-Hunt's supposed most easterly "metro-

polis", which is really situated ncar Ban Bon, on the left bank of the

Menam Chao Phya, some twenty miles south of Nnkhon Sawan

( Paknampo ). Further work with modern maps enabled me to plot its

position more exactly, as shown on the accompanying sketch-map

(Fig. 1 ). It lies about three miles south of r'yuhagiri, the main

north-south highway running alongside the other rampart. Con-

sequently it proved to be easily accessible. It is rather surprising that

it should have remained so long unknown, except or course to the Ban

Bon villagers, some of whom realized that the cat'lh works were the

ramparts of an ancient town.

MLiang Bon (Fig. 2 ), as the site may be called, has town status

by reason of its extensive outer enclosure, though it is smaller than I

had originally judged from the air photograph. The internal diameter

of the circular inner enclosure i:s only about 300 yards, that of an

average circular site on the Korat plateau, the total length of the outer

enclosure being about 1000 yards. Each enclosure has a moat,

now dry, averaging some 35 yards wide, and in the case of the outer

one often obliterated by agriculture. A small tributary of the Menum

running west of the outer rampart would have provided a good water

supply, and may have communicated with the moat. It would seem

that multiple moats and ramparts were not needed even i 11 the smaller

settlements of central Siam, as they were on the Korat plateau where

the people must have been much more exposed to the danger of attack.

It was during the first week of February 1964 that my wife and

I were enabled by the kind co-operation of Khun Dlmnit Yupho,

of the Fine Arts Department, to visit this site and

....... ---- --- - ---"----------

1 H.G. Quaritch "Wales, "An Early Duddhist Civilization in Eastern Siam ",

J.S.S., Vol. XLV. 1957, p. 5G.

2 H.G. QUAHITCH WALES

carry out some trial excavations. In this undertaking we were aided

by two members of the Department, Khun Mali Koksanfia and Khun

Raphisak Jaiwal, who proved most helpful.

The inner enclosure has a rampart outside the moat (Fig. 3 );

but not one inside it, as appeared from the air photograph, this ap-

pearance having been given by a ring of vegetation. The rampart,

some 20 yards broad at the base, stands at present about six feet higher

than the level of the ground in the enclosure. Traces of bricks were

seen at several places on the earth rampart when we walked round, and

at one point on the south they seemed to be of some depth, a trench

revealing laid bricks in two or three courses. I am unable to say what

was the purpose of this brickwork. Gaps indicated the positions of

former gateways at the cardinal points. The one on the south showed

earth abutments, jutting out from each bank of the moat, which would

have supported a bridge.

The interior of the inner enclosure was bare, except for occas-

ional trees and patches of scrub, most of it having been under bean

cultivation. Potsherds were frequently to be seen on the surface, and

were particularly abundant in the south-eastern part. So it was here

that I made arrangements with the owner of the land to make trial

excavations quite near to the moat, while about ten Ban Bon villagers

were engaged to work for us. Meanwhile we were shown a more or

less surface find, which had come to light when the ground was being

tilled in this area, and it certainly excited my interest. This was a

rather unusual terracotta votive tablet, a little over two inches high,

embossed on one side with a representation of the abiekha of Sri

(Fig. 4 A), a well-known Buddhist motif, which is found for example

on a Wheel of the Law from Nakhon Pathom. On the reverse of the

tablet (Fig. 4 B) there is a figure seated in the attitude of royal ease

which, despite its weathering, seems to show a laudable freedom and

mastery of design.

The owner of the land where we were to dig mentioned that

"enough beads to make a necklace" had been found after rain, but

he had given them to children who had lost them. From his descrip-

'

Fig. 1. Sketchmap showing position of Miiang Bon.

3

Mru;s

I

1

'I

c

I

I

I

..

Oo

/

31)

/

./

Fig. 2. Outline of Miiang Bon (based on an air photograph at the Pitt-Rivers Museum,

Oxford.) 1-4 positions of gateways ; A, inner enclosure excavation; B, outer

enclosure excavations; C, inscribed stone found here; lJ, approxnnate vusiuon

of stiipas.

Fig. :l. Miiang Bon: rnmpart and moat of inner enclosure. ( 1\uthor'N

Fig. 4. Votive tablet from inner encLosure of Mi.iang Bon. CFrom sketches made by f\:hun Raphisak).

Fig. 5. Mi.iang Bon: inner enclosure trial excavation. (Author's photograph)

Fig. 6. Examples of sherds. (Author's photograph)

\tijA\l; llll:\, .I TOll N OF \O!l!IIF!l\ 1>\ :i"ILIUJ'J :;

tion I should think they were common Kuala Sclinsing types, such as

have also been found at U T'ong.

A trial trench 23 feet long was dug at right nngles to the moat,

and ending 15 feet from it. Later this trench was extended right to

the moat and the pottery deposits were found to continue to within

six feet of the sloping edge of the moat. The upper six inches in the

trench consisted of soil disturbed by agriculture, with few sherds.

Below this was a layer of about 18 inches or undisturbed soil, with

potsherds, animal bones etc; that is to say the bottom of the habitation

level was about two feet beneath present ground level. A second

trench was then dug parallel to the first, about nine feet from it.

Then the intervening block (Fig. 5) was carefully cleared down to

natural soiL first the six inches of disturbed soil, then the 18 inches

with undisturbed deposits, which showed no stratification.

The slierds were of coarse reddish and wares, some

with simple impressed ornament (rigs. 6, 7, 8 ), while only a very

small proportion was cord-marked. The sherds were on the whole

very different from those previously found at the circular sites on the

Korat plateau.:; The site \vas probably not inhabited much af'ter the

Xth century A.D., since no gla;.cd pottery or porcelain was found.

ft is important to place sherds on record against the time when

documented material may be obtained !'rom many other Dvuravati

sites. Only then will it be possible to sec what conclusions may

emerge from their comparative st.udy. Besides the shcrds there were

also occasional pot-lid knobs, spouts and pottery counters. An iron

knife blade was found at a depth or 14 in., and another at 15 in. At

ll in. was found a small tin ring, probably f'rom a fishing net, and at

18 in. were found two broken portions of stone saddlc-qucrns and a

rubber, similar to others that have been found at Dvrira vali' sites.

Potsherds were also seen on the surface in many parts of the

outer enclosure. I decided to dig a trial trench (about 10 ft. long)

at a convenient spot some thirty yards south-east of the inner cnclo-

2

It may here be mentioned that at nnother D1:iravmi site, Ku B11a, I\atburi, a

collection of such glass bends, plus a few carnelian and other stone barrel

bends, all found locally, are now preserver! nt 'Vat Khan ( 18 ), Kij Bun,

3 J.S.S. Joe. cit., Figs. <1. G.

4 H.G. QUARITCH WALJ\S

sure rampart. The object was to see how the deposits compared with

those in the inner enclosure. We found a layer of similar sherds

extending from a depth of 6 in. beneath the surface down to 2H in.,

but within this layer the concentration of sherds was less than in the

inner town. From this one might be safe in drawing the conclusion

that, while the outer enclosure was added not long after the founding

of the original settlement, it was less densely populated.

At the bottom of the habitation level in this trench we were

fortunate in making a find such as is usually not to be expected in a

trial trench. This was the front half of an earthenware Roman style

lamp, the extant portion measuring 6 ~ in. long, ~ in. high, the mouth

still showing traces of blackening from a wick (Fig. 9 ). Apart from

the well-known bronze Roman lamp found at P'ong T'iik, there is a

complete earthenware one resembling the present one which came

from Nakhon Pathom, and is exhibited in the National Museum. Un-

fortunately such lamps cannot provide us with a date. Although

Roman prototypes in Italy may date from the first or second century

A.D., this type of lamp evidently became popular when introduced to

Dvaravati and may have been copied for centuries.

We were informed that lying by the border of a padi field in

the south-eastern part of the outer enclosure there was an inscribed

stone. We went to see this, and the owner of the field said that

formerly there had been two such stones, but the other one had been

destroyed. This one was about two feet high, roughly pointed at one

end (Fig. 10 ). It had evidently been a stele from which most of the

surface had flaked off, and only three or four isolated letters could be

distinguished. After it had been transported to the Bangkok Museum,

a rubbing was made which I subsequently sent to Monsieur Coedes.

He informs me that the style of the letters seems to indicate that they

date from about the VIIIth century A.D.

One day Khun Mali told me that he had heard of the existence

of six old stilpa-mounds, outside the town enclosure to the south-east,

and near to a modern wat. We went to inspect these and saw that

they were fairly large, the largest perhaps some forty feet in diameter,

and partly overgrown with vegetation (Fig. 11 ). The thorough in-

. . . . . ' .

I 3 INS----t

Fig. 7. Pot-rims I, :2 (above), :l, 1 ( belflw) C u t l u 1 1 ~ photograph)

Fig, 8. Sections of potrirns shown 111 Fig 7.

Fig. 10. The inscribed stone. (Author's photograph)

Fig. 11. Mi.iang Bon : one of the stiipa mounds. (Author's photograph)

Fig. 12. Stucco gures from a Miiang Bon stupa. (Author's photograph)

Fig. 13. Stucco dwarf caryatid from Mi.iang Bon stupa.

(From a sketch by Khun Raphisak )

Fig. 14. Dwarf earyatid from a Miiang Bon

stiipa. (Photo: Khun Raphisak)

Fig. 15. Stucco bead from a Miiang Bon

stfipa. (Photo: Khun Raphisak)

MliANG B O N ~ A TOWN OF NOBTUERN DV'ARAVAJ-1

5

vestigation of these would have entailed a larger task than I had

envisaged; hut I was later assured by the Director-General that their

excavation would be undertaken by the Fine Arts Department. For

the moment I was satisfied by the information I derived from the fact

that one of the stiipas had obviously been broken into, and some of the

objects that had been extracted were found to be in the possession of

another modern wat, situated not far away. These consisted of two

headless stucco figures of dancers or musicians, height 6! in. and 51,

in., (Fig. 12) two stucco dwarf caryatids, height 2ft., (Figs. !3, 14 ),

and a stucco head with foliage head-dress, height 14 in. (Fig. 15). All

these are unmistakably characteristic of Dvliravati art; but, on this

restricted amount of material, I should hesitate to ascribe objects

which may be rather provincial to a particular phase of it. However

the last mentioned object appears less stylized than rather similar

stucco pieces from P'ong T'!ik.

4

What appears to be certain is that

the st'llpas (five of them intact) are contemporary to MUang Bon, and

their full investigation may provide a wider range of material of great

interest.

Near the modern wat by the stlipa-mounds there was a rough

rectangular stone base measuring 41 in. by 21 in. Of a piece with it

were two stone feet, each 21 in. long, with sockets at the heels, on

which must have formerly stood a large image (Fig. 16 ). There were

several ancient bricks about, one measuring lOin. x ~ in. x 7in.

Here I will make mention of another circular village site, Ban

Thap Chumpbon, situated about three miles north of Nakbon Sa wan,

measuring under 300 yards in diameter and with moat and rampart.

l made only a superficial inspection of this place, and was shown the

spot where in 1961, in what appeared to be the remains of a brick

st'ii.pa, a number of Dvaravati style votive tablets bad been found, and

also some small votive stiipas, at least three of which were inscribed

with Buddhist credos. M. Coedes tells me that he has seen the rub-

bings of the inscriptions and that they date from the Vllth or Vlllth

century A.D. This evidence (bad it been published) might already

have been taken as sufficient to establish the northward extension of

Dvliravatr to this area; or again it might have been doubted, on the

4

Cf. P. Dupont, L'Archolof{ie M(;ne de DrOravari. Paris. 1959, page 113.

6

IT.G. QUAH!TCII VI'.\U:s

grounds that the Dvaravati objects could have merely been a hoard

placed there at some later time. Now, in view of the finds from

Miiang Bon, the material from Thap Chumphon certainly acquires

greater evidential value: indeed the two sites supplement each other.

It is not likely that Bon, which developed into a town, would be

situated right on the frontier. The stele we found there, probably of

the VIIIth century, was lying in the outer enclosure. Consequently it

seems likely that both Bon and Thap Chumphon were founded by the

end of the VIIth century. How much further north the authority of

Dvaravati extended it is not at present possible to say; but that that

distance was considerable is suggested by the legend that queen

Chammadevi from Lopburi evidently had to go as far afield as Lam-

phun to establish a new kingdom in the VIIIth century.

The archaeological and epigraphic discoveries made in recent

years both in central Siam and on the Korat plateau now give the

impression that the kingdom of Dvaravati, or at least its culture, was

virtually co-extensive with the subsequent kingdom of Siam, exclusive

of the Lao and Malay states. It seems to have controlled the Korat

plateau much longer than I thought when I wrote my previous article.

5

In this connection, I must, however, mention the apparently conflicting

deduction which M. Coedes draws from his study of two

that were recently found at Si T'ep. He has very kindly sent me a

proof of the section dealing with these two inscriptions, which will

appear in the seventh volume of his Inscriptions du Cambodge.

One of the new inscriptions ( K. 978) is a Sanskrit text of lhe

Vlth-VIIth century A.D., mentioning a King Bhavavarman, who

appears to be the well-known Bhavavarman I of Chen-la. From this

inscription we learn that he had enough authority in the Nam Sale

valley to set up Siva images on the occasion of his accession to

sovereignty. Incidentally this represents an abrupt change from the

religion of the former rulers of Si T'ep, who were Vai$l)avas. That

Bhavavarman I might well have made a raid, or temporarily extended

his power, into the Nam Sak valley in the disturbed times following

the break-up of Fu-nan is understandable enough. Briggs 6 has simi-

5 J.S.S., Joe. cit., p. 59.

6

r;.p. Briggs, Tire Ancifllf Kluner Empire, Philadelphia, 1951, p. 4::;,

1

larly taken the same king's comparable Tham Pet Thong inscription

in the upper Mun valley as indicating nothing more than the com-

memoration of a successful raid. Indeed Bhavavarman could well

have been the destroyer of old Si T'ep. For the next three centuries

r know of no evidence concerning SI T'ep, unless we can take the

recent finding of some large stone Dvaravati statues in a cave in a

mountain near Si T'ep as possibly significant. But Coedes concludes

with regard to this new Bhavavarman inscription ns follows: " L'im-

plantation de la puissance du Tchen-la, premier royaume khmer, au

moins a partir de cette epoque [early Vllth century A.D.], y est

d'ailleurs confirmee, d'une part par le fragment d'inscription K. 979

qui est en Khmer, et de l'autre par le l'existence des nombreux vestiges

khmeres signales par H.G. Quaritch Wales."

Now I did not record the finding of any Khmer remains at Si

T'ep which in my opinion were older than the XIth or XIIth century

A.D. The Khmer inscription K. 979, the second newly found one, in

script of the Xth century, can do no more than indicate the presence

of Khmer influence some time in the Xth century. Coedes has himself

recognized

7

the existence in the Karat region of a kingdom still

independent of the Khmer empire in the middle of the Xth century,

even if it employed the Khmer language in inscriptions as early as

the IXth. And he says of these Korat plateau inscriptions: ''Ces divers

documents epigraphiques assez disparates ont pour caraetere commun

d'etre etrangers au Cambodge, meme s'ils emploient la langue

khmere. Certains d'entre eux emanent peut-etre de pays ayant fait

partie, ou ayant reconnu la suzerainete, du royaume de Dvaravati. "

8

For the Khmers to have occupied the Nam Sak valley, while Dvaravati

dominated the Korat plateau and the Menam valley, would seem to

me to be a geographical and strategic impossibility.

7

G. Coedes, "Nouvelles donm!es epigraphiques Sllr de l'Indochine

centrale", Journal Asiatique, 1958, p. 127.

g ibid., p. 128.

DVARAV A Ti AND OLD BURMA

by

r]Jrofesso r o rdon r:H . ..uce

The so-called Burmese Era, dating from 638 A.D., should rather

be called the Pyu Era, for it is pretty certain that it was used, and

first used, by the Pyu of Sr"i (modern Hmawza, 4 miles S.E. of

Prome ).1 Indeed, I suspect that it is the date of the founding of that

city, the first capital of Burma in any large sense. Megaliths found

in the neighbourhood may well be older than that date; but I doubt if

anything Buddhist antedates it.

Old Mon inscriptions and late Burmese Chronicles lay great

stress on the founding; but the dates they give are far too early. In

the great Shwezigon inscription (c. 1100 A.D. )

2

the Buddha foretells

that the Rishi Vishnu (the future king of Pagan, Kyanzittha), "together

with my son Gavarhpati, and King Indra, and the (celestial architect)

Visvakarman, and Katakarma king of the Nagas, shall build the city

called Siszt" i.e. Sri Ksetra. The Chronicles

3

add that the Buddha

himself flew over and stood on Mt Po-u, north of the site, in order to

make his prophecy. Earth-convulsions, he said, would mark the

founding. The sea would retreat from its foundations (it is now 200

miles from the sea); and Mt. Popa, the 5000 ft. volcano in the heart

of Burma, would "arise like a cone out of the earth". Gavainpati,

the Rishi (Vishnu), Indra, the Naga king, Garur;la, Caqqi ( Di1rga)

and Paramesvara ( Shiva ), all were present at the founding. Indra

stood in the centre. The Naga king swished his head round, describing

the perimeter. The area enclosed by the walls, said to be 18 square

miles, is far larger than that of Pagan, whose walls, even allowing

for river-erosion, are barely 1 mile square. The difference lies in the

1. See C.O. Blagden. "The 'Pyu' Inscriptions", Epig. Indica Vol. XII, No. 16,

reprinted at J.S.R.S. Vol. VII Part l, PP 37-44 ( esp. pp. 42-43 ). The era was

used in the Pyu kings' urn-inscriptions, brilliantly read by Blagden. The period

covered .is from 3580, sc. 673-718 A.D. 718 is the last certain date in the history

of Pyu Sri K9etra.

2. Epig. Birm. I, II, Inscr. I, l'ace, A, ll. 30-33. The elate of the founding is given

in Inscr. III, l'ace C, 1.3: "in the year of my reaching ", i.e. 544 B.C.

according to Burma tradition.

3. See, e.g., Glass Palace Chronicle (trans!. from the ' Hmannan Yazawin' by Pe

Maung Tin and G.H. Luce, 1923, Oxford University Press) pp. 7, 14-15. The

date of the founding is given as 101 A.B., i.e. 443 B.C,

10

Gordon H. Lucc

presence or absence of ricefields. At Pagan there are none. At Sri

Ksetra, the northern half of the city, and much of the southern, is

ricefield.

All this fuss about the founding points, I suspect, to the fact

that it was the first strongly Buddhist capital in Burma. I used to

think that there was an earlier Buddhist capital. Chineses authors'

1

tell of plans made (but cancelled on his death) by Fan Shih Wan

(Sri Mara.), the great king of Fu-nan, to conquer the thriving port of

CHIN-LIN (or CiflN-CH'EN). This was near the beginning of the

3rd century A.D. Chin-lin was situated on a big bay over 2,000 li west

of Fu-nan. It was a populous kingdom, rich in silver and ivory. Chill,

the first syllable, means Gold, Suvanna. Two thousand li inland beyond

it, in a wide plain, was the kingdom of LIN-YANG (Liem-yang),

with an ardent Buddhist population of over 100,000 families, including

several thousand monks: "one goes there (from Chin-lin) by car-

riage or on horseback. There is no route by water. All the people

worship the Buddha". Two thousand li beyond Lin-yang, was NU-

HOU kingdom of "the descendants of slaves", over 20,000 families,

conterminous with Yung-ch'ang ( Pao-shan ).-There are some discre-

pancies in the texts, throwing doubt on whether .the ''great bay" was

the Gulf of Siam or the Gulf of Marta ban. I used to think the latter:

but now, in view of what we know about the antiquity of Dvaravatl,

and perhaps Haripunjaya, I incline to place Lin-yang in North Siam,

rather than in Central Burma. Lying equidistant between the sea

and Nu-hou Yung-ch'ang, it might be in either country.

Another reason that inclines me to place it in Siam is the re-

cent work of U Aung Thaw,

5

the energetic head of our present Burma

Archaeological Department. He has been excavating, 'Peikthano-

myo ', a large walled ruin at Kokkogwa, a hundred miles north of

4. For Chin-lin ( Chinch'en), ;#.!%" Lin-yang, and -:kll..,f!. Nu-hou, see

discussion at J.S.R.S. 1924, Vol. XIV, Part II, pp. 142-158; 1937, Vol. XXVII,

Part III, p. 2

1

10, n. I. The chief Chinese sources are Liang-shu, ch. 51 (Section

on Pu-nan ); Shui-ching-chu ch. 1, , 6 r

0

; T'ai-p'ing-yii-lan, ch. 787, f. 4 v

0

; 790,

f, 9 V

0

, 10 r

0

5. See Aung Thaw, Preliminary Report an the h";-;cavation at Peikthanomyo, 1959

(pub!. by the Asia foundation for the Archaeological Survey of Burma). A.S.S.

1959, PP 8-10 CBurmese), and Plates 1 to 28.

DVAHAVATI AND OLD 11

Sri It is certainly older than Sri U Aung Thaw has

revealed a number of large buildings and many interesting objects:

but, in spite of the name ("Vishnu City" ), hardly any Indian writing,

and little evidence of Indian workmanship, and none whatever of

Buddhism. Nor, I think, has he found megaliths. At Sri on

the other hand, almost everything dug up ( apart from megaliths )

shows the influence of India-whether Buddhist ( Hinayana or Maha-

yana) or Brahmanic ( Vaishnavaite ). The southern half of the city

is dotted with large cylindrical stupas, bell-like encased stupas, and

small vaulted temples with great variety of plan and sl1apc. There

are also cemeteries with pots of ashes ranged in terraces. The Pyu

kings still clung to megalithic customs: their ashes arc found in huge

stone urns, engraved with Pyu inscriptions, but otherwise 1 ike those

of the Plaine des Jarres in Laos.(i

Mr. Chairman, this is my first visit to Thailand. Let me admit

that I am appalled at my temerity in addressing Thailand's eminent

scholars about their antiquities. But with your permission, Sir, I

propose to try and compare the arts of Mon Dvuravati, as shown

especially in Dupont's book, with those of Burma: namely the Pyu of

Sri (7th-8th cent. ), the coastal Burma Mon (l(iima1l'iiadesa ),

and the inland Man/Burmese of Pagan ( 1 Hh--13th cent. ).

My first feeling, I confess, is how different they all arc-even

Dvaravati Mon and Burma Mon. There was little or no difference

between these Mons, either in language or race. The difference lay,

I suppose, in the different influences from India which informed them.

Dupont sees in Dvaravati Mon especially the influence of Amaravati:

and Ceylon. In Burma Mon, both architecture and sculpture, I sec

little Andhra influence except in the south. I only wish there were

more, for the Andhras were great sculptors.

I see hardly any Singhalese influence before the 11th century.

I see, on the other hand, the clear dominance of North Indian models,

at any rate at Pagan. Your ancient Buddhism was simpler and purer

than ours. It seems to date from before the wide diffusion of Shaivism

6. See M. Colani, Megalithe.\' du Haul-Laos, 2 vols., 1925 CParis, Ecole Francaise

d'Extreme-Orient). '

12

Gordon H. Luce

in Upper India. Our Buddhism, especially in the north (North Arakari,

Pagan and evenProme) had close contact with the Mahayanist, Tantric,

and Brahmanic schools of Pala and post-Pala Bengal. It was only, I

think, after 1070 A.D., with the obtaining of the full Pali Tipitaka

from Ceylon, that the great change to Theravada was finally possible

at Pagan. The chief agent in that change was King Kyanzittha, who

reigned from 1084 to 1113 A.D. Round about 1090, near the beginning

of his reign, he was building a Theravada temple, the Nagayon, on

one side of the road at Pagan, while his chief queen, (perhaps a lady

from East Bengal) was building a Tantric Mahayanist temple, the

Abeyadana, on the opposite side of the road. Kyanzittha's final

temple, the Ananda, which dates (I think) about 1105 or later,

7

marks

the final triumph of Singhalese Theravada in Burma.

LATERITE. Dupont says little about laterite architecture or

sculpture. At P'ong Tiik- one of your oldest site- Coedes noted plenty

of it:

8

buildings of brick and laterite, which foundations, round and

square, of laterite blocks, neatly arranged; high basement platforms

faced with laterite, with simple fine plinth-mouldings. My colleague,

Col. Ba Shin, who had the great privilege last year of visiting your

old sites under your guidance, thinks you may have here just as much

laterite-work as we have in coastal Burma. At P'ong Tiik, he noted

"huge laterite pillars and carved blocks for the waist and recesses of

the stupa". At the base of the Phra Fathom, "a lifesize torso-image,

a ten-spoke Wheel of the Law, 3 small stupas, a carved pedestal, a

large vase on a pedestal, and (perhaps) a litJga-all in laterite. Near

7. Dupont ( pp. 6, 57, etc.) follows Duroiselle (A. S.l. 191311, pp. 64-65) in giving

1090 A. D. as the date of the completion of the Anand a. I think this is much too

early. The Mon inscription cited by Duroise!le, which was later edited by Blagden

in Vol. III, Part 1, of Epigraphia Sirmmzica, records the building of the palace

( 1102 A.D.), not of the Ananda. The "Burmese oral tradition" that the king

"had the architect put to death, lest any similar edifice should be erected by any

of his successors", to which Harvey (History of Burma, P 41) adds the further

refinement that "at the foundation a child was buried alive to provide the building

with a guardian spirit", is just folklore cliche, not to say rubbish. It should not

be repeated in serious history, any more than Governess Anna's account of Gate-

in 1865 Siam -a libel finally exposed by Mr. A.B. Griswold in his King

Mongkut of Siam (Asia Society, New York, 1961).

8. See" The excavations at P'ong Ti.ik and their importance for the ancient history

of Siam", Joumal of the Siam Society, XXI, Part 3, pp. 195-209.

IlVAHAVATI AND OJ.IJ llllll\1\

Ratburi, "the Wut Mahathut built of laterite, together with its enclo-

sure-walls; also a seated Buddha image". At Lopburi, the Phra Prang

San Yot, "built entirely of laterite. with pediments and spires beauti-

fully carved"; and within the round-about across the railway-line,

'a ruin which looks like a hillock of laterite blocks, with two stone,

images of' Vishnu" (he thought). Finally, ncar Prachinburi to the

cast, " a huge laterite block, shaped like the m_I(la or a stupa ".

Was not Laterite the first native material. in the coastal regions

of both our countries, to be used for Buddhist and pre-Buddhist art'!

As for Burnt Brick, though hallowed by A ~ o k a s usc of it, it is a

foreign Indian word ( i!(haka) in nearly all our languages -Thai, Shan,

Mon, Khmer, Burmese, etc. Laterite was certainly the old building

and art-stone in Ramannadesa. It was used for drains, gargoyles,

square wells, ramps, pillars and pedestals, casings of relic-caskets; for

animal sculptures, platforms, city-walls and all the oldest Buddhas

and pagodas; for colossal monolith such as the Htamal6n seated Bud-

dha, 17 ft. 9 in. high. Such images soon lose their surface features,

but the beauty ol' their colouring (if not buried in paint unci plaster)

remains for centuries.

At Zolcthok

9

ncar our Keli:'isa, where some or the Rulqas turned

Buddhist and offered their "ropes of hair'' ( Mrm juk sok), they us-

sembled huge beams ol' laterite, artfully piled, to construct the pagoda.

All around there is a glorious congregation---all native monoliths or

reel iron claystone, skilfully carved: umbrellas with bead and tassel

fringes resting on octagonal posts, altars hour-glass shaped with double

lotus mouldings, knobbed pillars with table-tops, ends or ramps with

volutes, 'buds' for corner-posts with little niches for candles, four-sided

stupas, pinnaclcd, with four shrines for seated Buddhas, and all man-

ncr of carved stands with leaf-patterns. All arc in laterite. They

outblaze the noonday sun in April, yet keep their porous calm and

coolness. For sheer workaday beauty, what stone in the world can

beat it!

REREDOS. There is one great difference in iconology bet-

ween Mon and Pyu. The earliest Mon images, both in Burma and

9. Sec U Mya, Arch. Sun. Ind., Report 1934-35, pp. 51-52 and Plate XXI.

i4

Gordon H. Luce

(I think) Siam, were always in the round. With the Pyu, and usually

the Bunnans, they must be backed with a reredos (' tag,e '). It a

relic, I suspect, from megalithic religion. The oldest images at Sri

are massive stone reliefs, Buddhist or Brahmanic.L

0

But what

is massive is not the figure but the stone 'tage '. Right down to Pagan

times, even when both are made of brick, the 'tagt: ', often plain,

seems almost as prominent as the image. It has even recurred to me

that one could measure the decay of one religion and the advance of

the other by the relative thickness of 'tage' and image!

VAULTING. In the temples, the greatest difference between

Siam and Burma lies in the vaulting. From Pyu times (7th-8th cen-

tury), right through our Pag{m and Pinya periods, and (rarely) beyond,

the Radiating Pointed Arch has been the main, preserving feature of

Burma's architecture. No two Pyu temples are alike in plan; but all

employ the radiating arch. The graining of the four pendentives at

Sri Ksetra is sometimes crude and two-dimensional (e.g. the Bebe

shrine), but it can be perfect (e.g. the East Z6gu temple). This neg-

lected temple, as M. Henri Marchal realized,ll is a small masterpiece,

the prototype of Pagan.

Radiating arches have also been found in Old

but not

yet at Thaton. The Mons, even at Pagan, did not entirely trust the

radiating arch. At the centre of the arch way they usually insert a

lintel of carved or fossil wood. The original 'Mon' type of temple

appears to have been a square shrine, with elaborate plinth-mouldings

on the outer side, tall niches richly embossed above them, pre-

forated stone windows with pediments, dado, and Kirtimuldta frieze

and cornice. A lean-to corridor was later added, with perforated

windows on three sides, and a broad entrance-hall on the fourth. This

lean-to corridor had only a half -vault, which could not bear the shock

10. See, e.g., Arch. Surv. Ind., Report 1909-10, Plate L (r), "Stone Sculpture from the

Kyaukkathein Pagoda".

11. See his "Notes d' Architecture, Birmane, 1 o Est", with its excellent drawings

at B.E.F.E.O. t. XI, 1940, pp. 425-431.

12. See ].A. Ste.wart, "Excavation and Exploration in Pegu", J. Burma Research

Society Vol. VIr, Part I (Aprill917), pp. 17-18, 20. There are also radiating

arches in the modernized Theinbyu pagoda, N. NW. of Kamanat village, E.

of Pegu Old City.

DVAilAVATI- AND OLD BURMA

15

of earthquake, as full keystone vaulting could. That is why the

ridor roofs of so many of the' Mon' type of temples at Pagan, have

fallen in. The Old Bmmans, taught by Mon experience, avoided this

mistake: their fully vaulted temples have stood Lhe shocks of centuries.

Dupont is wrong in saying (on p. 125) that vaulting was not

used in Burma monasteries, partly because the spans were too broad.

There is great variety in plan of the brick monasteries of Pagan; but

all are vaulted. One monastery,

13

dated 1223 A.D. N.E. of

ethna temple, Minnanthu, has two large vaulted halls ( 44 x 20ft., and

40x 15 ft.), set at right angles to each other, with a mezzanine corridor

crossing between the spandrels. Sad to say, nearly all these daring

monasteries are in ruin, because the walls were too thin, quite

cal, and not buttressed; no allowance was made for the outward thrust

of the vaulting.

Where did the Pyu learn the art of vaulting?-Not, I think, from

the Chinese Later Han dynasty tombs in Tongking, as M. Henri

chal suggested;14 for there the style of bricklaying is quite different:

the brick's broad face being at right angles to the plane of the arch.l5

In Burma, as at Ni.i'landa

16

and in Central Asia,17 the brick's broad

face is always parallel to the arch-face. No radiating arches survive

in Eastern India, so far as I am aware, as old as those of Sri Ksetra.

But I expect the Pyu learnt their fine technique from North Indian

13. See Plate 5 of Mr. Braxton Sinclair's article, "The Monasteries of Pagan" in

J.B.R.S., Vol. X, Part T, reprinted at pp. 5858 of the Fiftieth Anniversary Pub-

lication No. 2. The Lernyethna dedications are recorded under date 585 s., in

Inscriptions of Burma, Portfolio I, Plate 73. The pillar is still in situ.

14. lac. cit .. PP 428, 435-6.

15. See, e.g., Q.R.T. Janse, Archaeological Research iulndo-China, Vol. I (f-Jarvard

University Press, 1947), Plate 7 (2), which shows "the undisturbed brick con

struction" of one of the Thanhhoa tombs. Or see G. Coedes. Les pe11p!es de fa

peninsule indochinoises (Paris, 1962), Pl. V Cbas).

16. Nalanda Monastery No. 1 (Granary) has two radiating barreJ.arches, between

vertical front and back walls, the bricks of voussoir being laid Cas in Burma)

parallel to the archface. Here wooden lintels are also usual. The date is thought

to be 9th cent. These vaults, says Dr. Ghosh, are "among the first specimens of

the true arch in ancient India": see his Guide to Nalanda ( Delhi 1959) p. 8.

17. See L. Bey lie, Prome et Samara (Paris, 1907 ), p. 99, flg. 71, for a sketch of an

8th cent. burrel-vault in Chinese Turkestan. Here too the broad face of the

bricks is parallel to the arch-face.

16

Gordon H. Luce

architects, whether from Bihar, Orissa or Bengal. Heavy rainfall and

earthquake may account for the disappearance of such vaulting, both

in Eastern India and at That6n.

MON PEDIMENT ( clec, clac).- For architectural ornament

the Pagan Burman was deeply indebted to the Mon. The Mon

pediment is the most conspicuous detail of Pagan architecture,

crowning or enclosing almost every arch and window. Sri, Goddess

of Luck and wife of Vishnu, is often seen in the top centre. This

goes back to the carved stone jambs and architraves of Buddhist

tora11as at Sanci,lS or to the entrance of the Jain Ananta Gumpha

Khandagiri, in Orissa. But the two elephants with trunks bathing

her, have passed at Pagan into floral arabesques. At the lower

corners of the pediment, there are spouting makaras. Sri and Makara

are, properly speaking, Vaishnava figures. King Kyanzittha, who

declared himself an Avatar of Vishnu, popularized the Mon clec at

Pagan, though it occurs earlier on the Nan-paya and the Nat-hlaung-

gyaung ( a Vishnu temple ). The word claco, a pure Mon word, oc-

curs in one of the Vat Kukut inscriptions at Haripunjaya;

1

9 and the

pediment itself crowns every tiered niche in that magnificent monu-

ment.20 Judging from photographs, I guess that the makams are

shown, but not the SRI. I do not know if the clac occurs in Dvara-

vati art. The two Mon words, K.yax Sri, ''Goddess Sri", have

passed into Burmese ' kyesthye ' as an abstract noun meaning

"splendour".

VOTIVE TABLETS.-Burma's art here comes nearest to that

of Dvaravati. For the origin of Votive Tablets-often shown by the

Buddhist Credo ( ye dharma hetuprabhava etc. ) stamped in Sanskrit-

Nagari, usually on the obverse-is clearly from N.E. India, especially

Bodhgaya. After comparison, not only with Dupont's book ( where

few tablets are shown), but also with Coedes' admirable article,

"Siamese Votive Tablets", published in the Siam Society's Journal,2

1

18. See e.g., H. Zimmer, The Art of Indian Asia, Plates Vol., Nos. 18, 27 CSanci).

19. See B.E.F.E.O. t. XXX, p. 97 (Vat Kukut Inscr. II, 1.4 ).

20. See The Arts of Thailand C ed. by T. Bowie, 1960 ), P 50.

21. J.S.S. Vol. XX (Part I,) 1926, pp. 1-23, with 15 plates. Reprinted in the

Fiftieth Anniversary Vol. I, pp. 150172 ( 1954 ),

AN!J OLD 17

also with notes made by Col. Ba Shin on his visits to the Bang-

kok and other museums, we have found 8 or 9 types of plaques in

Burma which arc exact, or close, copies of yours in Thailand.

( i) Coedes' Plate I (top) illustrates the First Sermon: the Bud-

dha seated between stupas in pralambanasana, dharmacalmnnudra, with

a Deer on either side of his footstool, and the Wheel of the Law below

it. Your plaque comes from P'ong Several variants, never

(I think) quite the same as yours but very similar, have been found

at

Sri

and Twant(!:!ri near Rangoon. A bronze

mould for such tablets has been found at Myinkaba, and is now in

Rangoon University Library.

( ii) A rare variety, from Nyaungbingan in Meiktila district,

shows the Buddha seated in the same attitude between two Bodhisat-

tvas, seated on the same throne in lalitasana.

21

i I do not know if

this variety is found in Thailand. But a third variety, oblong with

arching top, is shown in Coedes' Plate II, top, right und left corners.

Here the Bodhisattvas are standing, and three 'Dhyani' Buddhas arc

added at the top or the plaque. The plaques come from Budalung

and P'ra a! ready notes "an identical ta blct" from

Burma, "pictured by R.C. This comes f'rom Kawgun

Cave, 30 miles above Moulmein. There is a duplicate in the Indian

Museum, Calcutta, said to come from Sri Ksetra. We have a similar

oval plaque, also from Sri

(iii) Coedcs' plate III (centre) shows an oval plaque with

the Buddha seated in the centre preaching to 8 ( Coedes says 12)

22. Sec correction at J.S.LS. Vol. XXI. (Part :D, 192:3, p. lDG, n. 1.

23. See Thomann, Pagan, (Stuttgart, 192:.!), Abbildung 70 and P lOil. Bunn.

Archaeol. Neg. 2710 Cl92G-27). llrch, ,)'urv. lnd 1915, Part I, Plate XX (f),

and p. 24 U M ya, Votive Tablets of Burma, Part I, figs. 57 .(i2.

24. See U Mya, Votive Tablets of Burma, Part II, figs. 87 .88.

25. See A.S.I. 190G, Plate LIII, fig. 2, and p. 134.

26. Burm. Archaeol Neg. 2436 (1923-24). Arch. Sun1. Bun11. 1922, fh 11.

27. See Indian Antiquary 189t! plate XVI (top right).

28. See U Mya, V.T.B., Pnrt IT, figs. 53, 54.

is

Gordon H. Luce

persons, seated in ecstatic attitudes around him. It comes from Tharri

Guha Svarga. A good specimen of the same plaque, from Sri

is in the Indian Museum, Calcutta, and a worn specimen from the

same place is also shown by U Mya.

29

( iv) On the same plate (bottom right), coming from the

same cave, is a round Mahayanist plaque showing the Green Tara

(Syama or Khadiravan'i sitting in lalittisana, right hand on knee in

varadamudra. This also is in the Indian Museum, found at Sri

( v) Coedes Plate V (centre) shows a high triangular plaque

with the Earth-touching Buddha, royally adorned, mounted on three

elephant- heads, with many other Buddhas beside and above him.

This type was found at Bejraburi. Specimens have also been found

at Rangoon Tadagale.3

1

(vi ) Col. Ba Shin has a photograph of an oval plaque, show-

ing the Earth-touching Buddha seated between stupas within an arch

crowned with an umbrella. It is said to come from a cave in Khao

Ngu hill near Ratburi. The strong tall-torsoed figure with long arm

falling vertically, is found in East Benga1;:

12

but it is so characteristic

of Aniruddha's work at Pagan that I have ventured to call it 'the

Aniruddha type'. Aniruddha's own plaques have 2 full lines of San-

skrit/Nagari below the double lotus, containing the Icing's signature.:3:l

Others like yours, have 3 full lines, containing the Buddhist C1'edo.34

The former come from the Icing's pagoda, Pagan Shwehsanda w; the

latter from other sites at Pagan. A terracotta mould has also been

found.

(vii) Col. Ba Shin has 3 photographs of a plaque, squared at

the base, pointed at the top, which shows the same type of Earth-

29. V.T.B. Part II, :figs. 84, 85.

30. Cf. U. Mya, V.T.B., Part II figs. 86.

31. See U. My a V .T.B. Part I, Fig. 88.

32. e.g. N.K. Bhattasali, Iconograj)hy of Buddhist and Brahmanical Sculj>tures

in the Dacca Museum (Dacca, 1929), Plate IX (a).

33. See A.S.I. 1927, pp. 1623 and Plate XXXIX Ca); 1915, Part I, Plate XX (h).

U Mya, V.T.B., Part I, fig. 4.

:34. See U Mya, V.T.B., Part I, fig. 18, Mon Bo Kay, "Ye dhammii hetuppabhavii,"

Yin-yf:-lmm magazine, Vol. III, Part 9 (Feb. 1961), P 116.

DVARAVA'l'f AND OLD BURMA 19

touching Buddha, seated between stupas on a high recessed throne,

under an arch crowned with sikhara and stupa. They come, I think,

from Kaficanaburi.-This type, in Burma, we associate with Anirud-

dha's son and successor, 'Saw Lu ', whose title, stamped on some of

these plaques in Sanskrit/Nagari, is Sri Bajrabharava. These have only

I line of writing below the throne,3

5

while yours have two. Our Sawlu

plaques have been found so far only in the north, at Mandalay,

Tagaung, and Kanthida in Katha township.

(viii) Col. Ba Shin has also photographs of plaques, squared

below, arching to a point above, showing a similar Earth-touching

Buddha seated on double lotus, with 3 stupas below the lotus, as well

as 2 faint lines of what looks like Mon writing. They come from

Tham Rsi, Khao Ngu hill, Ratburi-Mr. David Steinberg of the Asia

found the lower half of a suntar plaque at Mokti pagoda,

at the mouth ofTavoy river. It is now with the Burma Historical Com-

mission. Several other plaques from the same site had Mon writings on

the back, showing that they were made by governors ( sambeit) of Tavoy

( Daway ), under king Kyanzittha (Sri Tribhovartaditya ).36

( ix) Finally, Col. Ba Shin has a photograph of a thick-rimmed

plaque from Uthong, Suphanburi, showing the Earth-touching Buddha

under an arch crowned with an umbrella, between 4 other small

Buddhas in two tiers. Below is a line of inscription in Old Mon

saying; "This Buddhamuni was made by Matrarajikar", governor of the

Madra, a people N.W. of India. Perhaps he was a minister of Kyan-

zittha who gave several of his ministers fanciful Sanskrit titles.-

Dozens of this type of plaque have been found at Pagan, E. of the

Mingalazedi.37 Often they have Mon writings on the rims. One is

to be seen in the Tresor at Pegu, Shwemawdaw pagoda.

THE EIGHT SCENES.-One large and important group of

votive tablets at Pagan, illustrates the Eight Scenes (

in the life of Gotama Buddha. These have a long history in Indian

35. See U Mya. V.T.B., Part I, fig. 38. A.S.B. 1918-52, Plate I (right).

36. See U Mya, V. T.B., Part I, figs. 79, 80. Cf. A.S.B., 1924, pp. 38-40; Ibid.

1959, Plate 31.

37. See U Mya, V.T.B., Part I, fig. 98.

20 Gordon H. Luce

art, from Gandhara onwards. At Old Nalanda one of the Pala kings

built a colossal image of the Earth-touching Buddha against a reredos

15ft. high and 9k ft. broad, showing the Eight Scenes.3

8

This, and

the many Pala carvings on black slate, must have spread the fashion

to both our countries. In Burma, at Sri only two fragments

of a votive tablet of the Eight Scenes have yet been found.

39

At

Pagan they are plentiful. They may be painted, as in Loka-hteikpan

temple, on a large scale, 18ft. in height.

40

They may be condensed

onto terracotta tablets barely 3 inches high. The finest are intricately

carved on what we call 'Andagu' stone, defined in the dictionaries as

Dolomite.

41

Not having previously seen mention of the Eight Scenes in

Thailand, I was delighted to read, in Artibus Asiae,

4

2 an artiCle by

Coedes: "Note sur une stele indienne d'epoque Pala decouverte i1

Ayudhya (Siam)". It is a small gilded stone, a little over 6 inches

high. The kind of stone is not stated; one would like to know whether

it is a stone common to Bengal and Thailand, or one peculiar to either:

for although the style is plainly Pa:la, the size is that of our 'andagu'

carvings, not of ordinary Pala black slate reliefs. The scenes shown

include the usual Eight:

1. Nativity,

2. Enlightenment,

at Kapilavatthu.

at Bodhgaya.

3. First Sermon, near Benares.

4. Great Twin Miracles, at Savatthi.

(bottom left corner )

(center)

( middle tier, left )

(middle tier, right)

38. See A. Ghosh, A Guide to Nalanda, PP 20-21. Burgess, The Ancient Monuments.

Temples, and Sculptures of India, Part II, fig. 226, Duroiselle, A.S.B. 1923, p. 31.

39, See L. de Bey lie, Prome et Samara, Plate V, fig. 2, and L'Architecture Hindoue en

Extreme-Orient, p. 245, fig. 198 (from the temple). A.S.I. 1910, Pl.

XLIX 7 and p. 123, (from the East Zegu). Col. Ba Shin reports that a complete

specimen (except for damaged rims) has been found 300 yds W. of the Li:!myet-hna,

Sri and is now in the library-museum of Shwehponpwint pagoda, Prome

h ;i" B d l

2

" Tl I 1

3 11

Town. He1g t 5 .t rea t 1 45 11c mess Th

40. See Col_ Ba Shin, Loka-hteikpan (Rangoon, 1962), pp. 10-12, and Plates 10, 13, 14,

16, 17a, 18a, 19a, 21.

41. See, e.g., A.S./. 1923, Plate XXXIII (d) and p. 123; 193034, Part I, p. 180 (items

4 and 5), and Part II, Plate C ( c, d). A.S.B. 1935, Plates 9 and p, 14.

42. Artibus Asiae, Vol. XXII 1/2, 1959, pp. 9-14,

5.

6.

7.

8.

IJ\'AHAVATI AND OLIJ II\ liMA

Descent from

Tavatin.1sa,

to Sarikassa.

Monkey's offering

of honeycomb,

ncar Vcs'iili.

Taming of Nata-

giri elephant, at Rajagaha.

Parini rvui.Hl, at Kusinagara.

(top tier. lef't)

(bottom right corner)

(top tier, right)

(top)

There are also 3 additional figures in the middle ol' the lower tier-the

Buddha sheltered by the Mucalinda Naga, flanked by two Buddhas

with outer hands on knee, and inner raised in abhayamzulra. Coedes

dates the carving 11th or 12th century, judging partly from the writing

of the Sanskrit/Pali Buddhist Credo engraved on the reverse.

The arrangement of these scenes is not rigid, except that the

ParinirvaJ}a is always shown at the top, and the Nativity at the bot-

tom; but the latter may be either on the left or the right, and the same

applies to the other scenes. Burma plaques sometimes add an extra

scene at the bottom centre; and several 'andagu' slabs udd, bet ween

the 6 side-scenes and the central Buddha, another series or 6 (or !:l )

scenes in intermediate relief', showing the Seven Sites'

1

:

1

in the ncigh-

boUJhood of the Bodhi tree, where the Buddha, according to the later

texts, spent the first seven weeks after the Enlightenment.

THE FAT MONK.- Dupont ( p. 87, and fig. 253 ) shows a re-

markable' votive tablet' from Wat P'ru Pat'on in which a Fat Monk,

seated with both hands supporting his belly (or is he in dhyamanuulra'!),

takes the place of the Buddha. rn one of his reports

4

1

Duroise!Ie men-

tions, without illustrating it, a similar plaque round in a mound near

Tilominlo temple, Pag{tn. Statuettes of the Fat Monk arc plentiful

in Burma, in stone, bron?.c, silver-gilt, bronze-gilt, plaster, terracotta

unburnt clay. They arc found frequently in old relic-chambers:

at Sri Rangoon, Pegu, Mandalay, Pagan etc., from the 7th to

the 17th Century. Perhaps the oldest is a stone statuette, once lac-

quered and gilded, found in the stone casket in the relic-chamber or

Kyaik De-ap ( Bo-ta-htaung) pagoda, Rangoon.

4

ii

'13. See, e.g., A .S.l. 193034, Part I, p. 180 (item 5 ), and Part II, Plate C (e): A .S.J.

1929, Plate LII (e) and p. 113; A.S.A. 1923, Plate llJ, f1g. 1, and pp.

44. A.S.!. 1928-29, p. 111.

45. A.S.B. 1948-52, Plate III a, o.

22

Gordon I-I. Luce

In Thailand, I believt< you call this Fat Monk K.acciJyana. -Is

this the 5th-6th century author of the first Pal i grammar, K.accayana

vyakarm.za? Or is it the eminent disciple of the Buddha, MalzUlwccana,

famous for his golden complexion? - The rich youth of Soreyya,

according to the Dhanunapada-auhalwtha (I, 324 ff ), wished that his

wife were like the latter: a prayer that seems improbable if he was

really so obese. In Burma we hardly know how to identify him.

Personally, I follow our venerable archaeologist, U Mya, in thinking

he is Gavainpati, patron saint of the Mons, and a sort of ' elder states-

man' in Buddhism, whose gilded images are mentioned in our in-

scriptions.46 But I know no text that says Gavatnpati was abnormally

fat. And Burmese scholars have suggested that the monk is the Great

Disciple of the Left, Moggallana, uncomfortably swelled by the

naughty Mara entering his belly, as told in the Maratajjaniya Sutta of

the Majjhinza Nikaya.41

THE DVARA VATI BUDDHA-IMAGE. - Our experts, Dr.

Dupont and Dr. Le May,

48

are pretty well agreed about the distinctive

features of the Buddha image in Mon Dvaravati. Dupont ( pp. 177-

185 ) defines three of them:-

( i ) the brow-arches are joined.

(ii) the figure seems almost naked, but sexless (''lc nu ascxue").

(iii) both hands tend to execute the same mudra.

For ( i ), Dr. Le May says "lightly outlined eyebrows, in the form of

a swallow springing ".

For ( ii ), he says "torso ... like a nude sexless body under a fine

diaphanous cloth".

For (iii), he distinguishes two types:-

( a ) the standing Buddha with right hand raised in abhaya

rnudra, or both in

(b) the image seated European wise ( pralambanl'tsana), either

in dharrnacakramudra, or with right hand raised, left in

lap.

46. inscrs. of Burma, Portfolio I, Plate 6, 11. 4-6, where gilded

tra C 1 ), Mokkallin C 1 ), and Gavathpati C 2 ), are mentioned.

47. See A.S.l. 192829, p. 110.

48. See LeMay, The Culture of Soutlz-J:,ast Asia (1954, London, Allen and

Unwm ), pp. 65 f,

He also adds other features:--

( iv ) spiral curls of hair, or abnormal size.

( v ) elliptical form of face.

( vi ) bulging upper eyelids.

(vii) the material never sandstone, but a hard bl uc-black

limestone.

How docs all this compare with our images in Burma.- I find

it difficult to say. Nearly all these features, except the last, occur in

some Burma images, both stone, bronze and terracotta. They arc

commonest perhaps at Pegu; but they occur everywhere from N.

Arakan to Sri And they do not exclude other, different feat-

ures. In many cases the images arc so old or damaged that \Ve can-

not be sure about the curls, the eyelids or the brow-arches. VIc can,

however, usually determine the mudrli and the "iisana. The Burma im-

age seated European wise, represents (with f'cw exceptions) tither the

First Sermon, or the Parileyyaka Retreat. In the former case hands

arc in r!lzannacahrannulra, with Wheel and Deer usually visible at the

base. But the j>ralamf)(mflsmuz is not obligatory in this scene. More

often the Buddha sits crosslcggecl in Indian fashion. In the Parikyyakll

scene he nearly always sits in Jmilambanasana, sometimes turned hulf-

lel't towards the Monkey in the right corner. He has usually almsbowl

in lap. The Elephant is generally shown in the lcl't corner, with un

irrelevant monk behind.

SJJJVIE MlJJ)lUI FOR FJ(J1'11 11/INJ>S. Images, seated or

standing, where both hands execute the same mudr7i, arc always, in

Burma, an;haic. Here I would readily admit Dvaravati influence:

with this difference, that standing images arc commoner in Dvaravati,

while seated images arc commoner with us. Here is a sunumuy ,of.'

the Burma evidence:-

From Sri come at least 4 such images, 3 seated cross-

legged, 1 standing; 3 in bronze, l in gold. All have both hands raised

in vitarkamudra. The gold image, seated right leg on left, was found

south of the Tharawady Gate, in a garden just outside it. 49 A beau-

tiful bronze, seated in much the same pose, comes from the octagonal

49. See A.S.J. 1929, Plate LI (g) and pp. 106-7. Burm. Arch. Neg. 3097, 3098

( 1928-29).

Gordon H. Luce

ruin at Kan-wet-hkaung-g6n.

50

Here the robe covers the left shoulder

only. A similar bronze image, much cruder in style, is clearly a Pyu

attempt to copy an Indian original, with features exaggerated, bulging

almond eyes, large hands propped on the robe, and legs awkwardly

superposed, right on left. It comes from a site west of Yindaik-

kwin.51 The standing bronze image, found by the Shwenyaungbin-

yo abbot near his monastery S. of Taunglonnyo village.

52

wears a

heavy pointed crown: but in all other respects he is dressed as a

monk, with an indented line across the waist, and plain robe spreading

behind the legs.

From the relic-chamber of a ruined pagoda at Twante, some

15 miles W. of Rangoon, comes a fine bronze image of the Buddha

seated in pralambanasana, his delicate hands raised from the elbow in

vitarkamudra. His robe covers only the left shoulder.

53

At Pagan, 3 bronzes and 1 terracotta illustrate this feature.

One small weathered bronze comes perhaps from Paunggu pagoda,5'1

now mostly fallen into the river, just N. of the junction of Myinkaba

Chaung and the Irawady. It is a Buddha seated cross-legged, right

leg on left, with large hands propped at the wrist, raised in abhaya-

mudra. With it was found another archaic bronze of the Pyu

Maitreya. I have a note also, written in Pagan Museum, of a similar

"small bronze of' Pyu' style, headless, with tiny round legs and feet

barely crossing, and both large hands in abhayamudra ". Another

bronze, from Pagan Shwehnsandaw,

55

shows the Buddha seated on

double lotus, right leg on left, with both hands propped at the wrist.

Here, I think, the attitude is vitarlwmudra. The Shwehsanclaw, built

by Aniruddha c. 1060 A.D. or earlier, contained some of the oldest

Pagan tablets and bronzes, including Pyu.56

--------------------------------

50. See A.S.l. 1928, Plate LlV ( b ) and p. 129 (item c). Burm. Arch. Neg. 3040

( 1927-28 ).

51. See A.S.J. 1929, p. 105, item ( v ). Burm. Arch. Neg. 3055 ( 192.8-29 ).

52. A.S.B. 1939, Appendix F, p. xii, no. 79. Burm. Arch. Neg. 4124 ( 1938-39 ).

53. See A.S.B. 1920, Plate II, figs. 1 and 2, and p. 25. Burm. Arch. Neg. 2179,

2180 ( 1920-21 ) .

54. It is now at Pagan Museum, oddly labelled as foui)d in a "stone mound W. of the

Myazedi, 4 furlongs W. of the main road". I guess that the reference is to

Paunggu pagoda.

55. Burm. Arch. Neg. 2721 ( 1926-27 ).

56. See Duroiselle, A.S.T. 1927, pp. 161-5 and Plate XXXIX (f).

iJVARAVATl AND OLD BURMA 25

The Hpetleik pagodas at Lokananda, 3 miles S. of Pagfm, are

probably older than Aniruddha. It was he, doubtless, who encased

them each with a corridor to hold 550 unglazed Jataka-plaques, the

finest in Burma. In doing so, he reorientated the pagodas so as to face

East, instead of North or West where the old stairways are still visible.

At the West Hpetleik, the North steps led up to the main niche in

the a1J{la or bell. Here a row of very antique bricklike tablets can

be seen, and 3 similar ones at Pagan Museum. They have long

tenons which ran back into the bell. Faintly visible in the centre is

a haloed Buddha of Dvaravati type, standing with Iarge

1

hands raised,

palms forward, perhaps in the pose of Argument ( vitarkamudra)

rather than Freedom from Fear ( abhayamudra). Of the three tiers

on each side, the upper one may hold stupas, the two lower ones

worshippers.

57

CONCLUSION.-Perhaps you will feel, as I do, that the really

distinguishing features of Mon, or any other art, are not really con-

tained in such rigid criteria. Useful as they are as workaday means

of identification, they do not contain the essence of works of art,

such as the many noble specimens from Dvaravati to which Dr. Le

May has introduced us. I do not think that we can rival these in

Burma. But our archaeological record of Ramai'ii'iadesa is far more

incomplete, I fear, than is yours of Dvaravati. And while we talk,

with some confidence, about the 'Mon' element in the early temples

of Pagan, we still write 'Mon' in inverted commas: for though we

see clearly that it is different from Burmese, we are not always

absolutely sure that it is Mon. To ascertain this, we shall have to

do much more excavation in Tenasserim.

57. See A.S.I. 1907, Plate L (d) and p. 127, where Taw Sein Ko suggested that

they represent "Dipankara ... prophesying that Sumedhn and Sumitta, a ilower-

girl, would respectively become Prince Siddhatlhu and his wife, Yasodhara.'' Cf.

A.S.B. 1908, pp. 11-12.

8 '' "''

ASIA

INDIA

.. KNOWN NEGRITO oR PYGHOID TYPES

0 OCEANIC NEGROIDS

AUSTRALOIDS

m INTER t-11;\E'D Ne:GRITIC PYGHOI DS

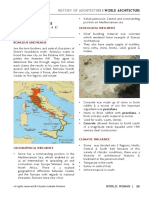

Ethnological distribution map of South Asi:J :;howing locations of I'ygrnoid, Negroid and Austr;tl.,id ral'ial t) I""'

.......

THE SOUTIII<:AST ASIAN NEGIHTO

Further Notes on the Ncgrito of South Thailand

by

/John r::n. q; ramlt

Professur Carleton S. Coon wrote in his recent publication

The Origin of Races", "One of the most controversial subjects in

human taxonomy is the classification of Pygmies, including principally

those of Africa, the Anclaman Islands, the Semang of the Malay

Peninsula, and the Philippine Negrito." In his reclassification of the

races he has placed the Asiatic Negri to in a grouping with the Austra-

loid proper, including as an additional race within the Australiod

subspecies of man, the Tasmanian and Papuan-Melanesian.

Negroids however, in the more traditional racial classifications,

arc usually divided into African Negroids and Oceanic Negroids, which

include the J>apuan-Melanesiun and the South East Asian Negroids.

Among the Asian Negroids arc the pygmoid Aetas of the Philippines,

the various tribal groups ol' the Andaman Islands in the Bay of Bengal

and the Semang Ncgrito uf' the Malay Peninsula.

Although a pygmoid type of' being, the Tapiro and the Aiome

Pygmy of Central New Guinea, the Bismark Mountains and the upper

Jimmi River, related by physical appearance and blood relationships

lo the Papuan has cvol ved, only the African Negro and the Negroids

o[' Asia ha vc produced true pygmo id versions of themselves. The

J'ormcr in the Bambuti Pygmies or the fturi Forest in the Congo and

other pygmoid groups extending into the forests or West Africa com-

prising some five known groups.

The Asian Ncgrito are today represented by surviving members

or some twelve tribal divisions consisting of approximately 2,000 in-

dividuals of the Andaman Islands where several tribes have already

ceased to exist or have been reduced to such low numbers that their

~ u r v i v l as a cultural entity is doubtful. The Andamancse Negrito is

probably one of the only pure examples of this subracc surviving to-

day since the Andnmans till very recent times have been completely

isulatccl from contact \\'ith the Asiatic Mainland. In the

roughly 25,000 Negrito li\e on several pf the larger islands ll(' the

;trchipelago. Some 3,000 Scmang Negrito, divided into seven known

bands, today inhabit the junglcd intcrinr of Northern Malaya and

northward on the Peninsula of Thailand as far N. Latitude. (Sec

Brandt 1962 ). Currently dwelling only in remote junglcd mountains,

the Negri to seem tu han: in the past also been lowland and

dwellers who were pushed into the interior by encroaching Malays or

Thai. The surviving tribes or the Andamans :-.till arc adept fisherman

and usc canoes in coastal waters.

At times the pygmoid bushman or the Kalahari desert of South

Africa is also classified among true pygmies.

The now extinct inhabitants or Tasmania have been described

as Ncgrito of medium stature with broad noses, thick lips, medium

racial protrusion, frizzly black hair and brachycephalic skulls in con-

trast to the present lnng headed, dolicocephalic, Australnid. h>r

Negritos to have reached Tasmania from the Australian continent, a

crossing or water at the Bass Straits would have been required by bual,

assuming a late migration southward from Asia proper. Even here

islands or the htrneaux, Curtis ami Kents would have facilitated such

a passage. Earlier migration from Asia could have been accomplished

by a short boat trip acrnss the straits scperating the Sunda and Sahul

shelves of present Indonesia which joined Horne(), Malaya, Sumatra

and Java in the former and Australia, New Guinea and Tasmania in

the latter, for some million years during the Pleistocene. An alternate

theory of Tasmanian origins by simple craft from the New I fcbrides

exists. However, more reasonable speculation is that Australia itself

was originally inhabited by Negrito people later replaced by Austra-

loids pushing south f'rum the Asian Mainland. Further support is given

this proposition by the facl that the Australian aborigine of today,

arc themselves divided into what appear to be three sub-types. One

a southern type with profuse body hair; a sparse haired dark northern

variety and a frizzly haired negroid stock from the rain forests of

Queensland, which intermixed and was largely replaced by the two

others. This Ncgritic element, it is suggested, is the remaining

nant of the original inhabitants.

The thidc wooly hair of t h t ~ Negrito has Parned him the name " Khon

Ngo" in Thai whieh likens his hair to the curly spincs on the outside of

tlw fruit 1\ambutan.

TIW .\SI\N NEI:lll"rO

Further cast, the Sahul shelf continued on to include several or

the larger Melanesian islands of the western Pacific. In tracing the

migrations or the Pulyncsians across the Pacific, Dr. Robert C. Suggs,

points out that there is reason to believe that some or the islands

reached by the Polynesians as early as P.OO BC were already occupied

by Negri to Pygmy or Negroid gruups. The place or '' Menuhenes ",

or small black forest dwarf's, armed with long bows dwelling in the

mountained interior of the islands is a living part or Polynesian and

Micronesian mythology and folk lore. The Negrito in all likelihood

moved into the island area on fool during the Pleistocene crossing

short distance of water with primitive craft where necessary.

During this early period, much or southeast Asia was occupied

by Negroids and primitive Paleo-Caucasoicl people. Which of' the

principle world races developed first is an unanswered question but

many authorities lean towards the Pygmy or Negrito as being one of

the earliest examples of primitive man although this is still not too

well documented by fossil remains. Contemporaneous development

or a perhaps slightly later origin is well for the Australoid

who has been described by Prof. E.A. Hooton an archaic form uf'

modern white man", or Puleo-Caucasoid. Mongoloid intrusion into

Southeast Asia is of a rather recent vintage and the area seems to have

been largely inhabited by a primitive caucasoid who derived wooly

hair and dark pigmentation !"rom whatever Negroid clements, probably

Negrito, that existed in the area at that time.

Evidence of an Auslraloid existence on the Asiatic Mainland

bas been purported by many physical relationships bet ween these

people and the remaining Veddalts of Ceylon as well as umnng several

hill tribes or southern India. It would he reasonable to include in

the Australoid classification all autochthonous Dravidian people of

south India. The Senoi ( Temiar and Semai) of' Central Malaya have

suggestions of certain primitive Australoicl characteristics as do the

Mokcn or Selung Sea Gypsies of Thailand's west coast centering in

the Mergui Archipelago of south Burma. Farther north such physical

types are found in the Hairy Ainu of Hokkaido, Sakhalin and the Kuril

Islands of Japan and in certain bearded Ainoid tribes of the Amur

River in Siberia. All of these are marginal people who seem to have

l'li'IWd h\ :Ill llllt:!llal pre;'.\!l't: [,, !ill' oltl!\:r Pl'llpiK'lY ut' !ltc

land ttLt,: .. :Ill individual<. jlr the lvpt

:1! the "''!'It:.: t.'\L't . .'Jll f,,r i.<dated t'\:lll!JdL:.

I lte .outltern Aw.tr:!ltdd \ariant. \lith

hllllld. quite prt,hahl;. dnl'ltped intn lhL: pre.ent Papuan. Tht:>t:

ph;. sit.:al pc r(lu;hly dat.d a < keanio. arL' cltaral'leri;ed

h;. d n:ry dtdicJcepllalic "ktdl, '' ith a indn v. ell ht.:lu\'. 75, a

deeply t'PIIt, Pl''!!nathi:.m am! ;1 :.kull \', iih

'itk' Skulh in han: been f'nund in :\mt.rica :1nd the

in l'a\'l>r i:; that the fir:;! prirniti

1

;L: 1t1 enter

'\urth America\ ia tilt.: Bering Strait:; were pf this mi\ed :\ustralnid-

'\letroid typl'. 1 were replaced at a tntH:h hy the

.\1onJ!tlltlitl ract v. hen it had den! oped It' it':' later :.tal!\: 111' Asian

dominance.

Btil.h .ft,,,. ;l!ld llaruld (il:tdwin in their writifl)!' un

tilt Jll'jllllatin:' .. r the l'<ntintnt the pll:;:-ihility uf

h;l\ inv the Ill'\\' \',ttl'ld. Thl: jli'C'>l'lll'l' or pygrnnid

t'ilaritcll:ri:.ti.:, in "me SPuth American Indian vr!IIIJ"' vaguely indi-

pu.:.ihk carl:. While tilt: rcmainill)' Auslra-

l(lid-0k!'l'>id V.Clc nradllally being pu:,hcd inl11 l ht: 11\llt:r Cd)!e:; of the

t'tllltinent. 111 hed. till: much later Mnllf'Ploith replal:ed them not

''nly in A'>1;1 h11t llli)rated on lP bccnrnc the Amerit.an \ll'

tlttLt\'.

rt:lnnam. ,,ftlw early mixed Au.,fraltid-I'h:gwid remains

;m.: in e; id..:tKc ''ll .. ,;vera I nf' t hL: 1 I : .. lands :.uch as among

the Tuala in till'< 'debe:; and alsP in Java. traces arc evident

in ',t:veral rc1rtainirw. lnd,mc;ian jungk people nn cast Sumatra and

lJ<ll'!lCI I <l' \\ 1.!J I.

( ln the ul' 1:1nn.:s in Indonesia, Dutch antllrupul11gists 111

l'J:\5 several identified a!; N!.!grito and

gave undocumented evidence of llll estimated age ul' 30,000 tu 40,000

years.

An 0lcgrito skull, which unl'ortunatdy cuuld not be

prupcrly dated. was discovered before 1921 under ten feet of alluvial

deposit beneath the Rio Pasig in Manila. Whatever the arrival date

TilE !:;tli

1

'I'IIEAST ASIAN NJo:t;){ITO :n

of the Negri to in this area may eventually pwve to he it appears his

extremely early presence seems i mlicutcd.

Going north into Southeast Asia, severn! Neolithic skulls and

fragments have been found indicating the early presence of' Negritos.

At Tam Hang and Lang-CLiom in Indochina a series of skeletal remains

excavated by French archaeologists have been iclcHtificd as Negrito.

Some indications arc that these people had started mixing with early

Mongoloids which apparently began filtering into the area in early

post-glacial times.

Dr. M. Abadie in 19:24 wrote that the Ho-Nhi tribes of Tong-

king had Ncgrito hair and a dark skin color. A skull found at Minh-

carn Cave in Annam has been identified as Negrito.

Early Chinese chronicles identify many or the dark skinned

jungle people or Indo-China as Negri to and called the people or Funan

(Cambodia) Negritos. Natives or the island of' Pulo Condorc, off

Vietnam, were identified as Negrito and ancient references identify

Negri to slaves in South China during the Seventh Century. Although

such evidence of Ncgritos is questionable due to lonsc interpretation

of the word "Negro'' the substantiated apparent intermingling or

Negroid, Paleo-Caucasoid and Mongoloid types in the Annamese area

seems to account for the dark skinned types which appears tn have

remained as late as the 'J"ang Dynasty ( 700 A.D.).

On the Thailand-Cambodian border, in the Cardamon Moun-

tains, dwell dark skinned jungle tribes called Piirr or Chong. Dr.

Jean Brengucs classified ulotrichi hair types among these people indi-

cating quite possibly the absorption or a Negrilo group into the now

predominantly Mongoloid population. Similm evidence of' Negroid

phenotypes throughout Southeast Asia indicate intermixture with an

earlier negroid type which existed in the area. LiLLie actual physical

evidence exists in Thailand and Burma of the existence of early Negri to

distribution patterns since little actual field exploration has been done

here. However, in many rural areas a strong negritic cast is evident

in remote communities of the western part of Thailand and continuing

south on the Peninsula through the isthmus of Kra.

,Iilli\ If. lii!ANilT

The May, Cuci and RuP tribes ul' the ut' <,luang-hinh

in Vietnam, though raci:dly mixed, show derm:nts in statme,

<.:.:phalk and nasal indi...:cs. sugge:-.ting :1 Ne!fritu

In India, the Kadar ut' the Anamalai !Jill ut' Cuchin and

Cuimhatore, a short dark PH'.muid aboriginal group strung negri-

tic clmracteristics. Based on physical and cultural the

anthropologists F.hrent'ds and Gulla have :-.uggcsted their atlinitics

with the Negritt,,d Malaya. Some suggested characteristics have also

been c>bser\'ed among the Naga ut' the Burma-India frontier area.

Still further afield in Taiwan, the researcher Tadeo Kano, has

uncovered traditions among Paiwan and Saisat aborigines

regarding former dark skinned dwarfs nn Taiwan. Certain areas ure

identified as Ncgritn burial sites and carry strong local taboos.

The question ul' whether a Negrilo is a separate :-.ub-spccitk

race a mutated Negm undergoing parallel in htl!h

Al'rica and Asia is still umcsolved. Certainly adverse living condi-

tions and iII nourishment will produce individuals of short stature

with examples the Mabri or Phi Tong Luang of north Thailand who

average for males 152.9 Cms. in height or just over the pygmy standard

ol' 150 Cms. The Veddahs, Lapps, some Eskimos and several jungle

tribes of Asia, At' rica and South America might he so calegori;t.ed where

because or poor rood and climate, through long selection, the tall

hereditary lines have gradually been clilllinali.!d producing a short

pygmoid type. 1 lowcvcr, it is also to be remembered that this is not

always true and equally unl'avorablc environmental conditions in other

instances permitted continuation of normal sized individuals.

The other possibility is that ur a specifit: mutation which was

then, through selective breeding or adaptability, developed to the

complete extirpation of the original normal size factor. '!'his would

lead to the ultimate development ot' a pygmy genotype. There is no

indication that a pygmy raised in normal surroundings would become

anything but a pygmy. Yet it seems peculiar that or all the divergent

varieties or man that only the Negroid would have produced a dwarf