Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

Surfing: A Cathartic Experience: Weber 1

Enviado por

api-283950834Descrição original:

Título original

Direitos autorais

Formatos disponíveis

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Surfing: A Cathartic Experience: Weber 1

Enviado por

api-283950834Direitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Weber 1

Meagan Weber

UWRT 1102-65

Julia Intawiwat

4/24/15

Surfing: A Cathartic Experience

Throughout history, individuals have sought out ways to obtain a new perspective on life

or develop an enlightened sense of purpose. For many people, specifically for those in coastal or

island cultures, that life-changing experience comes through engaging with the ocean in an

intimate and unusual way: surfing. As Chris McCandless noted, you do not need me or

anyone else to bring about this new kind of light in your life. It is simply waiting out there for

you to grasp it, and all you have to do is reach for it (Krakauer 41). Metaphorically speaking,

the ocean always exists, waiting for someone to reach out and experience its power with the

assistance of only a thin surfboard. Physical and psychological interactions, historical accounts,

and present day occurrences all prove that surfing can not only provide a cathartic experience for

an individual, but can also encourage social change or solidarity within broader cultures.

To comprehend why surfing has such a powerful impact, it is important first to

understand the techniques and practices of the sport itself. For the purposes of this paper, I will

focus primarily on the Hawaiian perspective of surfing, but also touch on some aspects of the

sport in California. There are six types of surfing found in Hawaiis history: board surfing,

outrigger canoe surfing, body surfing, body-boarding, sand sliding, and rifer surfing (Clark 19).

The type of surfing that most people think of when imagining the sport is board surfing. In this

subset, Hawaiians swim out slightly into the ocean, hold on to the board with their hands and

kick with their feet; they then swim further out, dipping their bodies underneath the water of

Weber 2

smaller waves until they finally find a wave large enough to ride back to the shoreline (Clark

19-20). Perhaps the cathartic experience begins when the individual realizes they must paddle

and push through forceful waves in order to reach the finale; the physical exertion of preparing to

surf the final wave requires a certain degree of motivation and dedication. A sense of

empowerment no doubt ensues after such a struggle and achievement.

This empowerment could be described in terms of what Bron Taylor denotes as soul

surfing. Soul surfing is a powerful, elemental activity that surfers indulge in for the pure act of

riding on a pulse of natures energy and contentment in the heart (Taylor 926). Interestingly,

the ocean is described as having an energy and a pulse, two concepts related with adrenaline,

excitement, and happiness. Consequently, those terms are related with cathartic experiences. This

insinuates that it is the power residing within the water itself that could act as the basis for an

emotional release. If the surfer feels a connection with the ocean, he or she can hypothetically

sense the energy residing within its waves and feed upon it. As one surfer said, when practicing

the sport, you connect spiritually and physically with all the elements around you; this is a part

of you (Walker 4). This notion is supported by the fact that many Hawaiian surfers see surfing

as a way of life, the greatest pleasure, vital to living, and even an all-consuming need (Clark

14). Surfing is many peoples heartbeat; it is their reason for existing. It can also provide

advantageous lifestyle benefits outside of the water. Soul surfers believe that engaging in the

activity allows them to obtain perspective and achieve peace in otherwise tragic situations

(Taylor 935).

Not only do the native people of Hawaii view surfing as an individualistic advantage, but

they also have shown historically that they can use it to promote social solidarity and cultural

revival. The primary example of this comes from the Hui O Hee Nalu, a group of thirty-five

Weber 3

Native Hawaiian men who worked together to prevent tourism and Calvinist colonialism from

destroying natural habitats and traditional surfing practices within Hawaii (Walker 1). They

essentially used their knowledge of surfing and of their land to protect what they held to be

important. Surfing was used as a tool to protect cultural identity. Additionally, the environmental

advocacy organization, Save our Surf, was founded in Hawaii in 1961; it sought to prevent

developments that would endanger surfing breaks and areas (Taylor 937). This depicts how

surfers in Hawaii have employed a cyclical method in preserving their history and interests. They

first work to save their culture by means of surfing, then they work to save surfing by use of their

culture.

In todays society, surfing is being used as therapy for a variety of diseases and illnesses.

Perhaps surfings most well-known and widely spread therapeutic advantage is for

developmental disorders. In Malibu, California, a couple has created an organization called

THERAsurf that utilizes surfing in the treatment of those with diseases on the autism spectrum

(Magruder). Kim Gamboa, one of the two cofounders of the institution, states that when disabled

children return to the shore after surfing in the ocean, they exude a sense of calm and

confidence and that some have actually shown developmental improvements in balance and

motor skills since beginning the program (Magruder). These changes and improvements indicate

that there is something psychological and even physiological in the act of surfing that creates a

higher state of well-being. Additionally, this organization also helps to show that surfing can

encourage social solidarity and inclusion; it encourages active involvement of a minority

population in a popular pastime of the state. As Gamboa also notes, to see the surfing

community connect with the special needs community is very special (Magruder). The

Weber 4

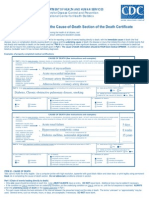

following picture accurately captures both the joy and the inclusive nature of the THERAsurf

program.

Given the colorful history and the present day applications of surfing, it is apparent that

the activity has both emotional and cultural significance. Within the individual, it encourages an

overwhelming feeling of joy, excitement, and power. Within a culture, it produces a common

interest and can be used to preserve the values of entire groups of people. Finally, within nature,

it promotes a connection between humanity and the forces of the earth. The sport requires a

reliance upon and a respect of the power of the ocean, but it also provides a cathartic release for

those who participate in it. Surfing, in many ways, is more than just a sport and more than just a

hobby; for countless people, it is a way of life and a reason for being.

Weber 5

Works Cited

Clark, John R.K. Hawaiian Surfing: Traditions from the Past. Honolulu: Unversity of Hawaii,

2011. WorldCat. Web. 25 Mar. 2015. <http://uncc.worldcat.org/title/hawaiian-surfingtraditions-from-the-past/oclc/794925343&referer=brief_results>.

Krakauer, Jon. Into the Wild. New York: Anchor, 1997. Print.

Magruder, Melanie. "Surfing as Therapy." Malibu Times. The Malibu Times, 24 July 2013. Web.

19 Mar. 2015. <http://www.malibutimes.com/malibu_life/article_50255c3a-f425-11e2b318-001a4bcf887a.html>.

Taylor, Bron. "Surfing into Spirituality and a New, Aquatic Nature Religion." Journal of the

American Academy of Religion 75.4 (2007): 923-51. JSTOR. Web. 20 Mar. 2015. <

http://www.jstor.org/stable/40005969?Search=yes&resultItemClick=true&searchText=su

rfing&searchText=experience&searchUri=%2Faction%2FdoBasicSearch%3FQuery%3D

surfing%2Bexperience%26amp%3Bacc%3Don%26amp%3Bwc%3Don%26amp%3Bfc

%3Doff%26amp%3Bgroup%3Dnone&seq=1#page_scan_tab_contents>.

Walker, Isaiah H. Waves of Resistance: Surfing and History in the Twentieth-Century Hawaii.

Honolulu: University of Hawaii, 2011. UNC Charlotte. WorldCat. Web. 20 Mar.

2015. <http://uncc.worldcat.org/title/waves-of-resistance-surfing-and-history-intwentieth-century-hawaii/oclc/794925379&referer=brief_results>.

Você também pode gostar

- Ride the Wave of Change: The Ultimate Guide to Life SurfingNo EverandRide the Wave of Change: The Ultimate Guide to Life SurfingAinda não há avaliações

- Freediving Manual: Learn How to Freedive 100 Feet on a Single BreathNo EverandFreediving Manual: Learn How to Freedive 100 Feet on a Single BreathNota: 5 de 5 estrelas5/5 (4)

- Swimming HandoutsDocumento13 páginasSwimming Handoutsangel louAinda não há avaliações

- Swim Fit Swimming - Swimming For Fitness And Health!No EverandSwim Fit Swimming - Swimming For Fitness And Health!Nota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (3)

- Essay PE3Documento1 páginaEssay PE3rjdc972Ainda não há avaliações

- Swimming HandoutsDocumento13 páginasSwimming HandoutsJoymae Olivares TamayoAinda não há avaliações

- Return to the Sea: The Life and Evolutionary Times of Marine MammalsNo EverandReturn to the Sea: The Life and Evolutionary Times of Marine MammalsAinda não há avaliações

- Prelim P.E SwimmingDocumento2 páginasPrelim P.E SwimmingPreciousmae Talay JavierAinda não há avaliações

- Surfing Research PaperDocumento6 páginasSurfing Research Paperapi-302531975Ainda não há avaliações

- Surfing SubcultureDocumento18 páginasSurfing SubcultureMartin McTaggartAinda não há avaliações

- Swimming Science: Optimizing Training and PerformanceNo EverandSwimming Science: Optimizing Training and PerformanceG. John MullenNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (1)

- SurfingDocumento5 páginasSurfingTunelyAinda não há avaliações

- Chapter 2 Aquatic ActivitiesDocumento5 páginasChapter 2 Aquatic ActivitiesAshly Mateo100% (1)

- Swimming Scientifically Taught: A Practical Manual for Young and OldNo EverandSwimming Scientifically Taught: A Practical Manual for Young and OldAinda não há avaliações

- Clearing the Coastline: The Nineteenth-Century Ecological & Cultural Transformations of Cape CodNo EverandClearing the Coastline: The Nineteenth-Century Ecological & Cultural Transformations of Cape CodNota: 5 de 5 estrelas5/5 (1)

- 4 PagespreadjhrealDocumento4 páginas4 Pagespreadjhrealapi-463291401Ainda não há avaliações

- Ocean of Self: An ocean diver explores the nature of consciousnessNo EverandOcean of Self: An ocean diver explores the nature of consciousnessAinda não há avaliações

- Module 2: Inroduction To SwimmingDocumento11 páginasModule 2: Inroduction To SwimmingJomir Kimberly DomingoAinda não há avaliações

- Wave 2 Manual DigitalDocumento60 páginasWave 2 Manual Digitalderekb100% (3)

- Ocean Outbreak: Confronting the Rising Tide of Marine DiseaseNo EverandOcean Outbreak: Confronting the Rising Tide of Marine DiseaseNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (3)

- Astonishing Book about New Swimming Invented and Collected the Swimming Savant More than 150 Swimming Strokes, Kicks, Tips and Great DrillsNo EverandAstonishing Book about New Swimming Invented and Collected the Swimming Savant More than 150 Swimming Strokes, Kicks, Tips and Great DrillsAinda não há avaliações

- Sharks in the Shallows: Attacks on the Carolina CoastNo EverandSharks in the Shallows: Attacks on the Carolina CoastAinda não há avaliações

- Fishers At Work, Workers At Sea: Puerto Rican Journey Thru Labor & RefugeNo EverandFishers At Work, Workers At Sea: Puerto Rican Journey Thru Labor & RefugeAinda não há avaliações

- Stung!: On Jellyfish Blooms and the Future of the OceanNo EverandStung!: On Jellyfish Blooms and the Future of the OceanNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (5)

- AquaticsDocumento26 páginasAquaticsVanessa Mae Delos SantosAinda não há avaliações

- Surfing and CultureDocumento8 páginasSurfing and CultureGuilherme PereiraAinda não há avaliações

- Truth and Myths About The Essence of SwimmingDocumento8 páginasTruth and Myths About The Essence of SwimmingPoseMethod100% (1)

- In a Perfect Ocean: The State Of Fisheries And Ecosystems In The North Atlantic OceanNo EverandIn a Perfect Ocean: The State Of Fisheries And Ecosystems In The North Atlantic OceanAinda não há avaliações

- Between the Sea and the Sky: Lived Religion on the Sea ShoreNo EverandBetween the Sea and the Sky: Lived Religion on the Sea ShoreAinda não há avaliações

- Sex, Drugs, and Sea Slime: The Oceans' Oddest Creatures and Why They MatterNo EverandSex, Drugs, and Sea Slime: The Oceans' Oddest Creatures and Why They MatterNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (14)

- The World's Beaches: A Global Guide to the Science of the ShorelineNo EverandThe World's Beaches: A Global Guide to the Science of the ShorelineAinda não há avaliações

- Douglas Booth - Ambiguities in Pleasure and Discipline - The Development of Competitive SurfingDocumento18 páginasDouglas Booth - Ambiguities in Pleasure and Discipline - The Development of Competitive SurfingSalvador E MilánAinda não há avaliações

- Lesson 1 Fundamentals of SwimmingDocumento13 páginasLesson 1 Fundamentals of Swimmingjayson gilbert susadaAinda não há avaliações

- Silay City Watersports and Recreation Park (Chapter I)Documento25 páginasSilay City Watersports and Recreation Park (Chapter I)Aisa Castro Arguelles67% (3)

- Wave 3 Manual DigitalDocumento63 páginasWave 3 Manual Digitalderekb100% (2)

- RoughdraftintroductonDocumento9 páginasRoughdraftintroductonapi-318345568Ainda não há avaliações

- Whales, Dolphins, and Porpoises of the Western North Atlantic A Guide to Their IdentificationNo EverandWhales, Dolphins, and Porpoises of the Western North Atlantic A Guide to Their IdentificationAinda não há avaliações

- The Complete Book of Striped Bass Fishing: A Thorough Guide to the Baits, Lures, Flies, Tackle, and Techniques for America's Favorite Saltwater Game FishNo EverandThe Complete Book of Striped Bass Fishing: A Thorough Guide to the Baits, Lures, Flies, Tackle, and Techniques for America's Favorite Saltwater Game FishNota: 5 de 5 estrelas5/5 (2)

- Swimming GGDocumento18 páginasSwimming GGClinton FabreAinda não há avaliações

- Jamaican Research PaperDocumento5 páginasJamaican Research Paperkhkmwrbnd100% (1)

- Crete Swim: An insider's guide to sightseeing from the waterNo EverandCrete Swim: An insider's guide to sightseeing from the waterAinda não há avaliações

- 5 Easy Pieces: The Impact of Fisheries on Marine EcosystemsNo Everand5 Easy Pieces: The Impact of Fisheries on Marine EcosystemsAinda não há avaliações

- All the Fish in the Sea: Maximum Sustainable Yield and the Failure of Fisheries ManagementNo EverandAll the Fish in the Sea: Maximum Sustainable Yield and the Failure of Fisheries ManagementAinda não há avaliações

- RM ORES BrochureDocumento4 páginasRM ORES BrochureSteve NelsonAinda não há avaliações

- Money and The Law of AttractionDocumento4 páginasMoney and The Law of AttractionJack KrenzAinda não há avaliações

- 1989 Book NewDirectionsForMedicalEducatiDocumento314 páginas1989 Book NewDirectionsForMedicalEducatiConceição Silva100% (1)

- Maclean Pathological Triad Article 2017Documento5 páginasMaclean Pathological Triad Article 2017linecur100% (1)

- Medical Office Procedures: KITAN, Maurine F. BSOA-3Documento5 páginasMedical Office Procedures: KITAN, Maurine F. BSOA-3naDz kaTeAinda não há avaliações

- G8 Q3 SUMMATIVE TEST - Performancde Task - StudentsDocumento17 páginasG8 Q3 SUMMATIVE TEST - Performancde Task - StudentsMay V CabantacAinda não há avaliações

- Mapeh 9 AssessmentDocumento4 páginasMapeh 9 AssessmentElmer John De LeonAinda não há avaliações

- Nursing AssignmentDocumento3 páginasNursing AssignmentVanny RosalinaAinda não há avaliações

- Volume 3 Issue 2 2023: Newport International Journal of Public Health and Pharmacy (Nijpp)Documento9 páginasVolume 3 Issue 2 2023: Newport International Journal of Public Health and Pharmacy (Nijpp)KIU PUBLICATION AND EXTENSIONAinda não há avaliações

- Pidato BHS InggrisDocumento4 páginasPidato BHS InggrisPutri altheaAinda não há avaliações

- Power of Thought Henry Thomas HamblinDocumento38 páginasPower of Thought Henry Thomas HamblinhabiotoAinda não há avaliações

- Calcium in Human Health PDFDocumento442 páginasCalcium in Human Health PDFMilan ValachovicAinda não há avaliações

- Reading Comprehension Chapter.Documento22 páginasReading Comprehension Chapter.Ajeet Singh Rachhoya100% (1)

- Fundamentals of Nursing (Midterm Topic 1)Documento7 páginasFundamentals of Nursing (Midterm Topic 1)Manuel, Precious Marie B.Ainda não há avaliações

- My Study Plan Guide For AmcDocumento7 páginasMy Study Plan Guide For Amc0d&H 8Ainda não há avaliações

- Healing Properties of Tai ChiDocumento32 páginasHealing Properties of Tai ChiMisty Hughey100% (2)

- Tata Trusts Annual Report 2021 22Documento100 páginasTata Trusts Annual Report 2021 22Shubham BeheraAinda não há avaliações

- Non Verbal LearningDocumento25 páginasNon Verbal LearningDruga DanutAinda não há avaliações

- Multiple SclerosisDocumento35 páginasMultiple SclerosisJc SeguiAinda não há avaliações

- Bulechek McCloskeyDocumento22 páginasBulechek McCloskeynikita priscilaAinda não há avaliações

- Week 1 PowerPointDocumento13 páginasWeek 1 PowerPointMilan FantasyAinda não há avaliações

- Approved Harmonized National RD Agenda 2017-2022 PDFDocumento90 páginasApproved Harmonized National RD Agenda 2017-2022 PDFJoemel Bautista100% (1)

- Australia Visa QuestionnaireDocumento5 páginasAustralia Visa Questionnairepmd20190707Ainda não há avaliações

- Blue FormDocumento2 páginasBlue Formalin_capilnean8371Ainda não há avaliações

- Chronic Disease Management and Remote Patient Monitoring: Research - Debate - Policy - NewsDocumento52 páginasChronic Disease Management and Remote Patient Monitoring: Research - Debate - Policy - NewsAlejandro CardonaAinda não há avaliações

- The Science and Fine Art of Fasting - Health Systems & ServicesDocumento5 páginasThe Science and Fine Art of Fasting - Health Systems & ServicesrumehuguAinda não há avaliações

- Diarrhea New Edited 2Documento82 páginasDiarrhea New Edited 2bharathAinda não há avaliações

- Diagnosis Holistik Kedokteran Keluarga PPT - Ulfi Nela YanarDocumento43 páginasDiagnosis Holistik Kedokteran Keluarga PPT - Ulfi Nela YanarUlfiYanarAinda não há avaliações

- Fact or FictionDocumento2 páginasFact or FictionClarixcAinda não há avaliações

- Boys Do (N'T) Cry Addressing The Unmet MentalDocumento7 páginasBoys Do (N'T) Cry Addressing The Unmet MentalJulz MariottAinda não há avaliações

- Cauze BoliDocumento90 páginasCauze BoliSeb SaabAinda não há avaliações