Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

Village Pointe Planning Paper Part II Final

Enviado por

api-283774863Descrição original:

Título original

Direitos autorais

Formatos disponíveis

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Village Pointe Planning Paper Part II Final

Enviado por

api-283774863Direitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Running head: PLANNING PAPER PART II

Village Pointe Planning Paper Part II

Shannon Harris, Victoria Grigorita, Sonny Pascale, Aubrey Hogge, Marian Gemender, Melissa

Johnston, Laura Pozo, Jessica Chamberlin, Cecile, Perez-Collantes

Old Dominion University

PLANNING PAPER PART II

2

Village Pointe Planning Paper Part II

The purpose of this assignment is to utilize the Health Planning Model to improve

aggregate health and to apply the nursing process to the aggregate within a systems framework.

Our aggregate is comprised of the residents living at Village Pointe (VP), a 60-unit retirement

facility that provides affordable housing for older adults. All residents must be 62 years of age or

older to apply to live at VP. The residents are diverse in age, gender, race, ethnicity, and marital

status, but all are well accepted into the VP apartment community. This aggregate was selected

due to the variety of health issues that are present in the older population in general, the

socioeconomic status of the residents at VP, and the established rapport between the School of

Nursing from Old Dominion University and VP. Utilizing previously gathered assessment data

and having an identified nursing diagnosis with specific outcomes, we implemented

interventions and evaluated outcomes to enhance the nutritional aspects of the aggregate as well

as improve overall well being and quality of life.

Planning

Health Problems of Aggregate

Health problems in the Village Pointe population were determined based on assessment

data gathered through surveys and open discussions with the residents during the assessment

phase of our planning project. The priority diagnosis for the aggregate is readiness for enhanced

nutrition related to deficient knowledge about healthy and proper food choices. This was

evidenced by 75% of the aggregate having doctor-diagnosed hypertension, 25% having doctordiagnosed diabetes, and the majority of the aggregate admitting to a lack of proper education on

appropriate nutrition. This diagnosis was made to assist in managing or preventing hypertension

and diabetes in the aggregate as well as to prevent continual consumption of non-nutritious food

PLANNING PAPER PART II

items. It was apparent that members of the aggregate lacked proper education on appropriate

nutrition because of statements they made about their diet consisting of food such as canned

vegetables, pre-packaged lunch meat, chips, and sodas as well as eating large portion sizes. This

priority diagnosis was made based on assessment findings and interest from the residents on

nutrition education.

The second diagnosis is impaired physical mobility related to decreased muscle

endurance and pain experienced from certain disease processes evident in the elderly population.

Readiness for enhanced self-care with regards to dental hygiene is the third diagnosis, which is

related to expressed interest about dental health and lack of knowledge on the importance of

regular dental checks. The fourth diagnosis, based on the previous assessment phase, is chronic

pain related to disease processes experienced by the aggregate as evidenced by 30% of the

residents stating that they experience chronic pain. The final diagnosis is knowledge deficit

related to advanced directives as evidenced by residents stating not being familiar with advanced

directives or not having one and expressing interest in learning more about them.

Priority Diagnosis with Goal and Objectives

Our priority diagnosis identified for our aggregate is readiness for enhanced nutrition

with a focus on managing hypertension and diabetes through an incorporation of a healthy diet,

which would also provide additional, associated health benefits. This diagnosis is related to a

lack of knowledge within the aggregate on what constitutes a healthy diet. Widespread interest in

initiating and maintaining a healthier diet was noted, including a desire for information on

nutritional items, recipes, and what foods to consume and what to avoid. This diagnosis is also

related to the 75% of residents with doctor-diagnosed hypertension, the 25% of residents with

PLANNING PAPER PART II

doctor-diagnosed diabetes, and the continual consumption of foods high in salt, such as

processed foods, and foods high in sugar, such as cookies and sodas.

Our ultimate goal is that the aggregate will report having improved knowledge about

healthy and balanced nutrition. Our first objective to achieve this goal is that 85% of the

aggregate will verbalize three benefits of adopting a healthy eating pattern by the end of the

teaching sessions carried out. Our second objective is that 80% of the aggregate will list a

minimum of three dietary recommendations that can assist in managing hypertension and

diabetes by the end of the teaching sessions carried out. The third objective is that 80% of the

aggregate will demonstrate appropriate selection of weekly meal planning that incorporates at

least five recommendations of healthy eating by the end of the teaching sessions carried out. The

fourth objective is that 85% of the aggregate will describe three snacking habits/patterns or

emotions that are detrimental to nutritional change by the end of the teaching sessions carried

out. Our final objective is that 90% of the aggregate will identify at least three positive benefits

to assist them in maintaining dietary changes by the end of the teaching sessions carried out.

These objectives were mutually agreed upon by the students and the aggregate through group

discussions and surveys that aimed to determine what topics the residents would be most

interested in learning about.

Alternative Interventions

An alternative intervention to accomplish our objectives of managing healthy nutrition

would be couponing. The residents at VP are low-income older adults with a limited amount of

money to buy groceries. Some residents stated that they have tried to buy healthier options for

certain food items but were unable due to financial restraints. Couponing would be a successful

alternative intervention for this aggregate due to the ease of being able to find coupons in the

PLANNING PAPER PART II

newspapers, which are delivered to VP, as well as being able to use Internet access to find

coupons online. Through implementing this intervention, residents would be able to choose

healthier items that they would be able to afford to ensure they are maintaining a healthy diet.

Another alternative intervention that would be beneficial for our aggregate is discussing

the benefits of shopping at a farmers market. There are various farmers markets in Norfolk and

surrounding cities that residents can attend whether through personal transportation or VP

transportation. The farmers markets have fresh fruits and vegetables available for purchase.

Furthermore, VP can receive vouchers that can assist in purchasing these items at a lower cost.

This alternative intervention would be successful for the aggregate because farmers markets

provide affordable, fresh produce that can directly assist in maintaining a healthy diet for this

population.

Intervention

The interventions implemented were chosen based on the research findings that the

students located. Poor eating habits and inadequate nutrition knowledge are major problems in

the United States, which can eventually lead to malnutrition and other chronic conditions,

including diabetes, hypertension, and coronary artery disease (CAD) (Craven, 2012). Living

with these issues significantly reduces the quality of life among the aging population. One

research study was conducted in order to assess the nutritional status and dietary habits of older

adults and analyze their association with nutritional knowledge (Turconi, Rossi, Roggi, &

Maccarini, 2012). Two hundred older adults took part in the survey. According to the results,

only 30% of the participants demonstrated adequate nutritional status and good dietary habits,

while the majority of subjects were overweight (Turconi, Rossi, Roggi, & Maccarini, 2012, p.

51). Moreover, people with healthy weight demonstrated greater knowledge in nutrition than

PLANNING PAPER PART II

people with a high body mass index (BMI). Based on these findings and the results of the

nutrition surveys that we conducted last semester, we concluded that our aggregate needs a better

understanding of healthy nutrition. By providing various educational sessions on how to improve

nutrition, the gap that has formed between knowledge and poor habits will be filled, which will

improve the overall health status of the aggregate.

Using teaching as an intervention will enable all those present to benefit from the

information provided, because teaching can serve both primary and tertiary levels of

interventions. Teaching represents a primary intervention for the portion of the aggregate that

does not currently have the disease in which the education provided is about; therefore,

prevention by education is implemented for those individuals. Teaching also represents a tertiary

level of intervention for the portion of the aggregate that is currently diagnosed with the

particular disease process. In this case, teaching is beneficial to help manage health conditions

and prevent further complications associated with them. The ultimate goal of teaching about

healthy nutrition practices is to maximize the quality of life for the aggregate. One systematic

review of 15 randomized control trials (RCT) was conducted in order to evaluate the

effectiveness of nutrition interventions for older adults implemented in community settings

(Bandayre & Wong, 2011). According to the results, nutritional education positively influenced

diet choices and helped to improve physical function among the participants. Moreover, the

authors concluded that more active forms of interventions, which involved active participation

and collaboration, demonstrated the most promising outcomes. We applied these findings as our

rationale by actively involving our aggregate in the teaching sessions. For example, we

incorporated food tasting, cooking class, question and answer sessions, and food label readings.

PLANNING PAPER PART II

The first teaching session covered positive benefits of healthy eating and how to

accurately read food labels. Discussion of how to read food labels is important to implement in

this aggregate, due to the high rates of those with hypertension and diabetes, to ensure they

understand how to find the amounts of sodium and sugar in products they purchase. The

aggregate was provided with a handout of examples of food labels to follow along with the

discussion and to identify certain sections of the label when asked (See Appendix A, figure 1).

Rationale for this intervention is supported by a study that was conducted in order to determine

whether knowledge in food label reading impacts quality of nutrient intake (Post, Mainous, Diaz,

Matheson, & Everett, 2010). The study surveyed about 3,700 adults with and without knowledge

in food labeling. According to the results, those who had knowledge of reading food labels

consumed fewer amounts of calories, saturated fat, and sugar and consumed greater amounts of

fiber. These results suggest that implementation of teaching on how to read food labels is of great

benefit.

The second teaching session introduced healthy eating patterns and the use of MyPlate in

order to increase awareness of portion sizes. Each member was given a plate that was divided

into recommended portion sizes, and in each section there was a list of foods that should be used

to fill that portion of the plate during meals (See Appendix A, figure 2). The next few teaching

sessions had a focus on diabetes and hypertension in order to present the residents with

information that is helpful for their specific health issues. The pathophysiology of each condition

was discussed as well as signs and symptoms and how nutrition can be used to help manage the

conditions. Also, handouts were utilized in these sessions for the aggregate to have something to

look at while they listened (See Appendix A, figures 3 and 4). Another teaching session was

focused on meal planning so as to provide the residents with healthy meal suggestions. The

PLANNING PAPER PART II

aggregate was provided with reduced sodium recipes for full meals and also received a sample of

one of the reduced sodium crock-pot meals.

The next nutritional teaching focused on healthy snacking because the majority of the

aggregate admitted to snacking throughout the day. The rationale for this intervention is that

snacking plays a vital role in daily nutrition intake. One RCT was conducted to find an

association between snacking and nutrient intake among 123 postmenopausal women with high

BMI (Kong et al., 2011). According to the findings, snack meals served as a good source of daily

fruit, vegetable, and fiber intake. However, the findings also demonstrated that unhealthy choices

of snacks might lead to weight gain. Therefore, in order for our aggregate to benefit from

snacking, during this session, the residents were given suggestions and handouts on how to shop

for and prepare easy and nutritious snacks (See Appendix A, figure 5). In addition, nutritious and

easy-to-make snacks were provided, including frozen yogurt-covered fruit and

cucumber/cheese/turkey sliders.

The final nutrition teaching was implemented by a registered dietician. The dietician

answered questions that the residents had about nutritional aspects of hypertension, diabetes, and

other conditions (e.g., arthritis) that could assist in managing and/or preventing them. Having the

registered dietician assisted with tertiary intervention by helping residents diagnosed with

hypertension and diabetes manage these conditions. Also, it assisted with primary intervention by

preventing these conditions in residents who have not been diagnosed. This intervention was

successful because it allowed the residents to have questions answered by someone who has

more experience in the nutritional world and provided them with more clarity in different aspects

of nutrition with certain health conditions.

PLANNING PAPER PART II

Secondary intervention was also implemented throughout the semester by monitoring

vital signs, height, and weight weekly. The vital signs were taken first before any teaching

session, which helped get the group active to participate in the teaching discussions. The

rationale for this intervention is that weekly tracking of blood pressure and heart rate is one

method for early detection of hypertension and can also be used to note when a known case of

hypertension is not being controlled by medication and diet. Hypertension is one of the major

problems in the US; however, it can be easily treated, preventing life-threatening complications

such as stroke and CAD (Craven, 2012).

Regular blood pressure screenings are of great benefit and easy to implement in

community settings; however, they are not routinely done. The authors of one study conducted a

blood pressure screening in a rural area on a random sample of 150 adults that were 50-years-old

and above (John, Muliyil, & Balraj, 2010). According to the results, hypertension was detected in

almost half of the participants, but only 25% of those people were aware of their status prior to

the study (John et al., 2010, p. 68). Furthermore, 64% of those who were referred for further

evaluation initiated hypertension treatment within three months (John et al., 2010, p. 68). These

findings suggest that there is a tremendous benefit to implementation of blood pressure screening

for detection and initiation of treatment for hypertension. If done on a regular basis, blood

pressure screening can help to detect prehypertension, which would help in preventing the

development of hypertension itself. Therefore, regular blood pressure screening that we

implemented with VP residents is of great benefit and supported by research. Taking vital signs

enriched teaching sessions regarding healthy nutrition due to their significance when it comes to

eating habits and changes needed.

PLANNING PAPER PART II

10

Barriers

Barriers confronted during the Village Pointe experience included weather, attendance

issues, financial barriers to the students, and physical barriers to exercises. Weather played a role

in attendance due to heavier snowfall during the winter months that accumulated on the ground.

This limited both the residents ability to traverse the property in order to make it to the Village

Pointe community room from Village Gardens and also the students ability to commute to

Village Pointe for one of the regularly scheduled events. This was handled by combining

multiple teaching sessions into the following meeting time.

A concentrated effort was paid towards building up attendance with weekly flyers and

attempts to go door to door. Weekly flyers were created and sent to Delores Harris who posted

them on the Village Pointe and Village Gardens announcement boards. Unfortunately, there was

a restriction on door-to-door outreach. Supervision was required and this outreach could only

occur at certain times of the day, and because of government housing restrictions, any form of

solicitation needed to be approved in advance. Despite the restriction, the students were given

approval to go door-to-door, but due to communication issues amongst the Village Pointe staff,

those attempts were canceled. Instead, the students continued to use flyers to promote

attendance.

Another barrier the students faced was the financial expense of attracting residents to

participate in weekly events. Residents requested games and prizes to be present every week. To

address this barrier, the students explained to the residents that entertainment was funded by the

students and not by the university. However, students made use of limited financial resources by

shopping for prizes at dollar stores and limiting the number of prizes given to two or three per

PLANNING PAPER PART II

11

meeting. As a result, the number of residents in attendance decreased over time to a smaller but

more consistent group.

With respect to exercise, the students had to address the barrier of limited mobility among

the aggregate. Limits in strength, balance, and endurance were addressed by implementing

stretching exercises as opposed to more physically active exercises, encouraging the residents to

use chairs to support themselves during stretching exercises, and by slowing the pace of the

exercises so as not to fatigue the aggregate. Positive reinforcement, one on one instruction and

assistance, and easy-listening music were incorporated to help make a more positive experience

for the aggregate.

Evaluation

The main goal, or the expected outcome, of our interventions is that the aggregate will

report an increase in knowledge about balanced nutrition. In order to achieve this main goal,

different interventions were implemented, such as how to read nutrition labels, appropriate snack

options, dietary recommendations to control hypertension and diabetes, and positive benefits of

eating a healthy diet. After six weeks of implementing the necessary nutrition-related

interventions, we administered a brief, twelve-question post-quiz to the residents based on the

five objectives established during the assessment phase (See Appendix B). We determined that a

multiple choice post-quiz would be an adequate form of evaluation because it enables the

residents to recall information that was covered. This post-quiz was written at a seventh-grade

reading level, questions were simple and brief, and familiar vocabulary was used with the

intention of making the post-quiz easy for the aggregate to comprehend, which would enable a

more reliable evaluation of outcome achievement. Also, a large print (14 point font) and a simple

style type (Times New Roman) were used to make the post-quiz easy to read. To ensure that our

PLANNING PAPER PART II

12

evaluation tool could be easily read and understood, technical jargon, medical terminology, and

multiple connective words were avoided (Bastable, 2007).

In order to evaluate the effectiveness of our interventions, the questions in the post-quiz

were individually graded and grouped by which objective they tested. The scores of the questions

covering the same objective were then averaged together in order to determine what percentage

of the aggregate met the objective. There were two multiple choice questions that covered

information regarding the first objective, which focused on verbalizing two methods of adopting

healthy eating patterns. Residents scored 100% on these questions, surpassing our goal of 85%.

Our second objective, which covered dietary recommendations to manage hypertension and

diabetes mellitus, was evaluated with four multiple-choice questions. Our goal of 80% was not

met, as only 64% of the aggregate correctly answered these questions. The third objective, which

focused on appropriate selection of weekly meal planning, was evaluated with two more

multiple-choice questions. This objective was unmet because while our goal was 80%, only 64%

of the aggregate answered these questions correctly. Our fourth objective, which covered

snacking habits, was met because 93% of the aggregate answered the evaluation questions

correctly. Our fifth goal regarding positive benefits of dietary changes was also met because the

residents scored 100% on the respective questions. A chart comparing our expected and actual

outcomes can be found in Appendix C, figure 1.

Also, blood pressure and weight were measured weekly. Although all of those who

attended meetings had their vitals taken, there were 8 residents who attended meetings on a

regular basis. The data gathered from weekly blood pressure and weight assessments can be

found in Appendix C, figure 2. There was a decrease in a majority of the systolic and diastolic

blood pressures among the residents based on our assessment from both semesters. The

PLANNING PAPER PART II

13

aggregate as a group lost 2.6 pounds with one aggregate losing approximately 8 pounds (See

Appendix C, figure 2).

Limitations

There were several limitations to the process used in evaluating the desired outcomes.

The sample size of those who took the nutrition post-quiz was only seven, which is significantly

less than the 10 to 20 residents who attended teaching sessions in the previous semester. Because

the attendance of the events is optional and Village Pointe prohibits soliciting, this could be

resolved by making events more enticing with more games and prizes. Also, some of the

residents were not attentive while taking the post-quiz, which may have influenced the scores,

resulting in lower scores, specifically in the hypertension and diabetes sections. This could be

resolved by reading the questions aloud to enable the aggregate to fully understand and fully

participate in the evaluation process. The environment where the evaluation was conducted

might have also affected the results. Residents trickled into the community room while the postquiz was being taken, which provided distraction and made it difficult for the aggregate to focus.

Also, creating one post-quiz as opposed to multiple post-quizzes was a limitation to the

evaluation process. It would have been more beneficial to create a post-quiz after each teaching

session to better evaluated the residents understanding of each topic. Finally, recording of vital

signs was inconsistent because some residents either refused to have their vital signs

assessed/recorded or some did not attend events regularly.

Recommendations

After spending two semesters with the aggregate, recommendations have been

established for future groups of nursing students working with Village Pointe. The first

recommendation is to create a questionnaire for the aggregate members to take upon first

PLANNING PAPER PART II

14

meeting with them. The questionnaire would be a way to determine what they are interested in

learning about during their time with the nursing students. By catering the lectures or activities to

what the aggregate is interested in, there is an increased probability for maximal participation.

Another suggestion to take into consideration during the first meeting with the aggregate is to

refrain from including games or food as rewards right away. The members love to play bingo and

enjoy trying new foods, but students noticed that if these activities were not advertised for the

next meeting, fewer residents would attend. Bingo was a popular activity to include occasionally

as long as the residents know that there will not be games every week.

A positive addition to the Village Pointe meetings would be collaboration with the

physical therapy students at ODU. Weekly exercises were already established in the residents

routine with the nursing students, but this interdisciplinary approach can increase their

knowledge on mobility, proper body mechanics, and appropriate exercises for individuals with

arthritis. A final recommendation is to create assessment and evaluation tools that are appropriate

for the aggregates education level. The wording should be simple and easy to understand. It is

also suggested that instead of having the aggregate members read each question themselves, one

nursing student should read the questions and answer choices aloud. This may keep residents

more focused and can make it easier for the aggregate to comprehend each question.

Implications and Conclusion

Through time spent with the aggregate at Village Pointe, teaching was implemented to

include nutrition and its use to manage hypertension and diabetes. Through surveys and ongoing

assessment it was determined that this teaching was effective in community health education.

Nurses can utilize this process, including assessment, implementation, and evaluation within a

community setting to provide preventative and curative education to a specific population. For

PLANNING PAPER PART II

15

example, community health nurses can provide nutritional education as a method of treating or

preventing common health issues, such as diabetes and hypertension. Another implication for

community health nursing involves the importance of providing access to the older population

for regular vital sign check-ups, especially blood pressure, as a means of early detection and

treatment of hypertension. The interventions implemented at Village Pointe show that the nursing

process can be used to successfully provide care in the community setting.

PLANNING PAPER PART II

16

References

Bandayre, K., & Wong, S. (2011). Systematic literature review of randomized control trials

assessing the effectiveness of nutrition interventions in community-dwelling older adults.

Journal of Nutrition Education & Behavior, 43(4), 251-262.

doi:10.1016/j.jneb.2010.01.004

Bastable, S. B. (2007). Nurses as Educator: Principles of teaching and learning for nursing

practice. Sudbury, MA: Jones and Bartlett Publishers.

Craven, R., Hirnle, C., & Jensen, S. (2010). Fundamentals of nursing: Human health and

function. Seattle, WA: Wolters Kluwer

John, J., Muliyil, J., & Balraj, V. (2010). Screening for hypertension among older adults: a

primary care "high risk" approach. Indian Journal of Community Medicine, 35(1), 67-69.

doi:10.4103/0970-0218.62561

Kong, A., Beresford, S. A., Alfano, C. M., Foster-Schubert, K. E., Neuhouser, M. L., Johnson,

D. B., & ... McTiernan, A. (2011). Associations between snacking and weight loss and

nutrient intake among postmenopausal overweight to obese women in a dietary weightloss intervention. Journal of the American Dietetic Association, 111(12), 1898-1903.

doi:10.1016/j.jada.2011.09.012

Post, R., Mainous, A., Diaz, V., Matheson, E., & Everett, C. (2010). Use of the nutrition facts

label in chronic disease management: results from the national health and nutrition

examination survey. Journal of the American Dietetic Association, 110(4), 628-632.

doi:10.1016/j.jada.2009.12.015

Turconi, G., Rossi, M., Roggi, C., & Maccarini, L. (2012). Nutritional status, dietary habits,

PLANNING PAPER PART II

nutritional knowledge and self-care assessment in a group of older adults attending

community centers in Pavia, Northern Italy. Journal of Human Nutrition and Dietetics,

26, 48-55. doi:10.1111/j.1365-277X.2012.01289

17

PLANNING PAPER PART II

18

Appendix A

Handouts

PLANNING PAPER PART II

Figure A1

19

Figure A2

Figure A3

Figure A4

PLANNING PAPER PART II

20

Figure A5

PLANNING PAPER PART II

21

Appendix B

Post-Quiz

1. What ingredients can be used as a healthy substitute for salt? (Select all that

apply)

a. Butter

b. Black pepper

c. Garlic

d. Lemon

2. How can you decrease arthritis using nutrition?

a. Take vitamin E supplements daily.

b. Use butter as lotion over joints with pain.

c. Eat red and purple foods and take a fish oil supplement daily.

d. Eat green vegetables at least once a week.

3. What is an example of a healthy snack?

a. Popcorn

b. Blueberries and yogurt

c. Chips and salsa

d. Sugar free cookies

4. How many meals should you eat in a day?

a. One big meal at night

b. 3 portion-sized meals, with snacks in between

c. Only eat lunch and dinner

5. How many food categories should you divide your plate to have the

adequate nutrients according to the American Diabetic Association?

a. 3

b. 4

PLANNING PAPER PART II

22

c. 1

6. What are these food categories?

a. Vegetables, grains, and protein

b. Sweets, grease food, vegetables

c. Salty food, sweets, grains

7. Which of the following is a positive benefit of eating a healthy diet?

a. Decreases energy

b. Maintains/Decreases weight

c. Hinders self-esteem

d. Worsens hypertension/diabetes

8. Positive benefits of eating a healthy diet include promoting energy,

sharpening the mind, and improving digestion.

a. True

b. False

9. What are some ways we can manage DM?

a. Regular Blood glucose testing

b. Regular Exercise

c. Hemoglobin A1C testing

d. Drinking Alcohol Beverages

e. A B & C only

10.What are the two types of Diabetes Mellitus?

a. DM type 1 and type 2

b. DM Type a and type b

c. Cushing Diabetes

d. Parkinsons Diabetes

11.Which of the following can help manage high blood pressure? (select all that

apply)

PLANNING PAPER PART II

a. Reduce sodium intake

b. Increase calcium intake

c. Increase saturated fat intake

d. Choose foods with a heart-check mark

e. Rinse canned vegetables

12.True or false. The DASH diet is recommended to help manage high blood

pressure.

a. True

b. False

23

PLANNING PAPER PART II

24

Appendix C

Evaluation Charts

Figure C1

Figure C2

Você também pode gostar

- V Grigorita Progress SummaryDocumento16 páginasV Grigorita Progress Summaryapi-283774863Ainda não há avaliações

- Victoria Grigorita Resume 2015Documento2 páginasVictoria Grigorita Resume 2015api-283774863Ainda não há avaliações

- Chn470amended FinalgradehealthteachingpaperDocumento31 páginasChn470amended Finalgradehealthteachingpaperapi-283774863Ainda não há avaliações

- V Grigorita Grand RoundsDocumento18 páginasV Grigorita Grand Roundsapi-283774863Ainda não há avaliações

- V Simonyakina Ob PaperDocumento12 páginasV Simonyakina Ob Paperapi-283774863Ainda não há avaliações

- Philosophy Project 300Documento5 páginasPhilosophy Project 300api-283774863Ainda não há avaliações

- Running Head: Client Case Study 1Documento14 páginasRunning Head: Client Case Study 1api-283774863Ainda não há avaliações

- V Grigorita Philosophy of Nursing-1Documento9 páginasV Grigorita Philosophy of Nursing-1api-283774863Ainda não há avaliações

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItNo EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (838)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeNo EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (5794)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)No EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Nota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (98)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceNo EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (894)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingNo EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (399)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureNo EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryNo EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (231)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaNo EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (265)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerNo EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (271)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersNo EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (344)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaNo EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (45)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnNo EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (234)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyNo EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (2219)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreNo EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)No EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Nota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (119)

- Elimination DietDocumento22 páginasElimination Diettheboss010100% (1)

- 013 Seafood Dishes PDFDocumento38 páginas013 Seafood Dishes PDFusama0% (2)

- 4ds0315e P2 (F)Documento1 página4ds0315e P2 (F)nagravAinda não há avaliações

- Confectionery Fats From PO and PKODocumento5 páginasConfectionery Fats From PO and PKOluise40Ainda não há avaliações

- Chicken RecipesDocumento89 páginasChicken RecipesAravindan SadhanandhamAinda não há avaliações

- Repaso de Preguntas Tipo ExamenDocumento1 páginaRepaso de Preguntas Tipo ExamenAlberto Linan MartinAinda não há avaliações

- 4-6 Months Baby DevelopmentDocumento8 páginas4-6 Months Baby DevelopmentHyeAinda não há avaliações

- Reaction PaperDocumento3 páginasReaction Papergemkoh0250% (2)

- KISAN HUT FOUNDATION PRICE LISTDocumento10 páginasKISAN HUT FOUNDATION PRICE LISTGurleen NandhaAinda não há avaliações

- Who Says These Restaurant ExpressionsDocumento3 páginasWho Says These Restaurant Expressionsclaudia gomezAinda não há avaliações

- How To Measure Dry Ingredients Quick ConversionsDocumento2 páginasHow To Measure Dry Ingredients Quick Conversionsehm-ar. SilvaAinda não há avaliações

- Soal UTS Bahasa Inggris 3-DikonversiDocumento5 páginasSoal UTS Bahasa Inggris 3-DikonversiHakim AzisAinda não há avaliações

- Soal Akm Bahasa Inggris Kelas Ix Final - Tendri SolongDocumento11 páginasSoal Akm Bahasa Inggris Kelas Ix Final - Tendri SolongSakat SakatAinda não há avaliações

- Fanelli Et Al., Copra, Palm, AB, April, 2023Documento8 páginasFanelli Et Al., Copra, Palm, AB, April, 2023Fina Mustika SimanjuntakAinda não há avaliações

- English Day ACERODocumento12 páginasEnglish Day ACEROAlejandroAinda não há avaliações

- Module Fish PreservationDocumento31 páginasModule Fish Preservationmelissaembuido565Ainda não há avaliações

- Countable Nouns: Things I Can CountDocumento16 páginasCountable Nouns: Things I Can CountFrida Magda SumualAinda não há avaliações

- Daily breakfast, lunch and dinner menu for a weekDocumento1 páginaDaily breakfast, lunch and dinner menu for a weekKevin JoseAinda não há avaliações

- The Potato and The Industrial RevolutionDocumento2 páginasThe Potato and The Industrial RevolutionharpreetAinda não há avaliações

- Penelitian Bakso Pilihan KonsumenDocumento10 páginasPenelitian Bakso Pilihan KonsumenEstri MahaniAinda não há avaliações

- Hoc Guan's Eight Decades as a Critical Player in CondimentsDocumento3 páginasHoc Guan's Eight Decades as a Critical Player in CondimentsJeric Louis AurinoAinda não há avaliações

- Presentation On Fruit JuiceDocumento16 páginasPresentation On Fruit JuiceNkAinda não há avaliações

- Attention: Mam Junilyn Ella Tfyd Tayabas City: Nawawalangparaiso Resort and HotelDocumento3 páginasAttention: Mam Junilyn Ella Tfyd Tayabas City: Nawawalangparaiso Resort and HotelHazel Jael HernandezAinda não há avaliações

- Development of Food Tourism The Role of Food As A Cultural Heritage of Malwan (Maharashtra)Documento7 páginasDevelopment of Food Tourism The Role of Food As A Cultural Heritage of Malwan (Maharashtra)International Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyAinda não há avaliações

- Question No 1-4 My School: 7. Eating - Like - Some - I-Cake in Good Sentence IsDocumento4 páginasQuestion No 1-4 My School: 7. Eating - Like - Some - I-Cake in Good Sentence IsEl MinienAinda não há avaliações

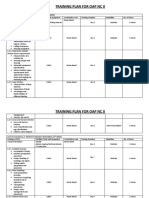

- Training Plan For Oap NC Ii: Unit of Competency 1: RAISE ORGANIC CHICKEN (1 Week)Documento11 páginasTraining Plan For Oap NC Ii: Unit of Competency 1: RAISE ORGANIC CHICKEN (1 Week)Judy Mae Lawas100% (1)

- The History of Chocolate (Key)Documento2 páginasThe History of Chocolate (Key)Cuong Huy NguyenAinda não há avaliações

- Nutrition and Digestion 1Documento11 páginasNutrition and Digestion 1findpeace313Ainda não há avaliações

- Morgan Lagueux - Final Draft Research PaperDocumento6 páginasMorgan Lagueux - Final Draft Research Paperapi-548143942Ainda não há avaliações

- ZerocalDocumento15 páginasZerocalFaiyazKhanTurzoAinda não há avaliações