Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

Running Head: Correcting Vitamin A Deficiency 1

Enviado por

api-287737986Descrição original:

Título original

Direitos autorais

Formatos disponíveis

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Running Head: Correcting Vitamin A Deficiency 1

Enviado por

api-287737986Direitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Running Head: CORRECTING VITAMIN A DEFICIENCY

Correcting Vitamin A Deficiency:

Reducing the Prevalence of VAD of Preschool-Aged Children in India

Leo Ontiveros

Adam Hernandez

Nicole Keally

Alejandro Valenzuela

California State University, Los Angeles

CORRECTING VITAMIN A DEFICIENCY

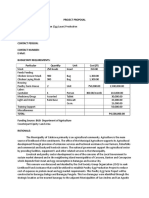

Table of Contents

Title Page.1

Table of Contents.2

Abstract....3

Introduction......4-6

Literature Review...7-10

Description of the Population of Interest..10-11

Summary....11

References12-14

Appendices....15

CORRECTING VITAMIN A DEFICIENCY

I.

Abstract

Around the world and especially in developing countries, nutrient deficiencies are a lot

more common than one might suspect. This proposal focuses specifically on vitamin A

deficiency (VAD) as it relates to children in the country of India. VAD in children is associated

with blindness, limited growth, weakened immune systems, increased severity of infections and

increased mortality rates that have been well documented. In India, more than 60% of preschool

aged children are vitamin A deficient, and according to the World Health Organization (WHO),

half of them will go blind every year.

Our proposal lays out a plan whose goal is to reduce the prevalence of VAD in India.

Working together with WHO to take advantage of the infrastructure in place, we propose a

mobile health center similar to a blood drive. The objectives are to reduce blindness caused by

VAD in children, expand nutritional education among the population, and decrease the number of

cases of VAD as a whole by introducing supplements and vitamin A fortified foods. We will also

emphasize breastfeeding in our education in hopes of increasing the number of mothers who

chose to breastfeed. Based on the research, VAD is caused by a variety of issues; biological,

nutritional and socioeconomics. Past peer reviewed research suggests that supplementation alone

is not enough to solve the problem, implying that education and introducing a well-balanced or

fortified diet along with supplementation is ideal.

Keywords: vitamin a, deficiency, VAD, correcting, supplementation, VAS, xerophthalmia,

blindness, nutrition intervention, children, preschool, India

CORRECTING VITAMIN A DEFICIENCY

II.

Introduction

A. Vitamin A deficiency (VAD) is a major public health nutrition related problem that exists among

young children, especially in developing nations. VAD can cause blindness, limit growth,

weaken the immune response, increase the incidence and severity of infections, and increase the

risk of death. Xerophthalmia, the inability to produce tears resulting in dry eyes, is a condition

associated with vitamin A deficiency and further increases the risk of morbidity and mortality.

Approximately 130 million preschool-age children are vitamin A deficient worldwide (West,

2003) and in India alone it is estimated that 62% of all preschool-age children are vitamin A

deficient. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), an estimated 250,000 to 500,000

of the children experiencing vitamin A deficiency go blind every year, half of them dying within

12 months of losing their eyesight.

B.

a. The goal is to reduce the prevalence of vitamin A deficiency in preschool-aged children in India

by providing a short-term solution via supplementation in combination with a long-term strategy

largely based on food fortification and nutrition education.

b. The expected outcome is to decrease VAD related blindness, ensure proper growth, reduce

xerophthalmia and lessen the risk of morbidity and mortality. With VAD correction the immune

response should be enhanced, decreasing the incidence and severity of infections, resulting in an

improved quality of life.

c. The impact on the area of interest is to work in conjunction with the World Health Organization

to take advantage of the infrastructure they have in place to further promote the importance of

breastfeeding, vitamin A supplementation, and food fortification.

d.

i.

ii.

Reduce VAD related blindness by 50% in 1 year.

Expand access to help by creating a mobile movement using vitamin A awareness trucks, similar

iii.

iv.

to a blood drive.

Identify and correct vitamin A deficiency in preschool-aged children via supplementation.

Workshops will provide education and support for women to practice proper breastfeeding.

CORRECTING VITAMIN A DEFICIENCY

v.

vi.

Increase the rate of mothers breastfeeding from 25% to 50% in 1 year.

Introduce fortified Roti bread, new foods such as fortified whole-grain bread and identify foods

rich in vitamin A to grow in the area.

C. Inclusion criteria were as follows:

Children of preschool-age (6 months-5 years)

Vitamin A deficient

Vitamin A supplementation

Both mothers who breastfeed and those who do not

Exhibit symptoms associated with vitamin A (xerophthalmia, blindness, infections, limited

growth)

Programs who have attempted to intervene

Exclusion criteria were as follows:

Children aged under 6 months or over 5 years

Children of more economically developed countries

Data that predates 2009

Search for relevant studies:

The studies in this review were obtained through electronic databases. The

electronic databases PUBMED, SCIENCEDIRECT and Google Scholar were

searched using the following keywords: vitamin a, deficiency, VAD, correcting,

supplementation, VAS, xerophthalmia, blindness, nutrition intervention, children,

preschool, India. The databases were searched for the period of January 2009 to

February 2015. Title and abstracts were examined and, if the abstracts met the

inclusion criteria, the full text of the article was retrieved.

Critical appraisal, data extraction and analysis:

CORRECTING VITAMIN A DEFICIENCY

The abstract of every article was read and then the full article was obtained. The

inclusion criteria was applied resulting in publications that were related to vitamin

A deficiency in India. The following data was summarized in the literature review

section below: causes of VAD, health concerns, factors contributing to VAD,

hindrances to program effectiveness, program benefits, and nutrition intervention.

Further analysis and comparisons of the findings are reported below.

III.

Literature Review

Malnutrition is the main underlying cause of VAD as a public health nutrition related

problem, insufficient vitamin A in the diet can lead to lower body stores and failure to meet

physiological needs to support tissue growth, resistance to infection, and establish a normal

metabolism. VAD is characterized as low serum levels of retinol (<20 g/dL). Prolonged

inadequate intake of vitamin A causes liver stores to become exhausted, leading to damage in

cellular function along with other associated risks of vitamin A deficiency (Groper & Smith,

2013).

Laxmaiah, A. et al., 2011 researched preschool-aged children (6 months to 5 years) in

India with VAD and found that the major health concerns associated with these children are night

blindness, conjunctival xerosis, bitot spots, corneal ulceration, keratomalacia, and total blindness.

Night blindness occurs when rhodopsin is compromised in the rod cells of the eye. Without

adequate amounts of vitamin A trans-retinal cannot be converted back to cis-retinal when light

CORRECTING VITAMIN A DEFICIENCY

hits the eye. Xerophthalmia, as referenced in the introduction, is a result of inadequate mucus

production from the loss of goblet cells in the conjunctiva along with the enlargement and

keratinization of epithelial cells known as corneal xerosis. As xerosis exacerbates, corneal

scarring, ulcerations and softening of the cornea (keratomalacia) may transpire which can lead to

corneal perforation and ultimately blindness. Vitamin A deficiency can also result in Bitots

spots, characterized as small, white, foamy-looking accumulations of sloughed cells (Groper &

Smith, 2013).

The following are factors contributing to VAD: illiteracy, low socioeconomic status,

occupation and poor sanitation (Laxmaiah, A. et al., 2011). Gebremedhin, 2014 found that

families of higher socioeconomic status were associated with lower rates of VAD. Another factor

of VAD is a cultural belief system of scheduled castes, scheduled tribes, and other backward

classes that contribute to the delay of VAS and exacerbate VAD (Laxmaiah, A. et al., 2011). This

system of castes results in a certain population receiving better health care than others. Education

also contributes to VAD, supplementation is predominantly given to mothers who are educated

compared to those with no education (Semba, Pee, Sun, Bloem, & Raju, 2015).

However, in order to properly combat VAD there are systematic blocks hindering the

implementation and distribution of vitamin A supplementation (VAS). A major gap in the

research pertaining to VAS is poor vitamin A program coverage and improper distribution of

VAS, with roughly only 34% of children receiving a dose/year (Chow, Klein, & Laxminarayan

2010). It is a problem stemming from the governments lack of political stability and regulation

on a federal, state, and local level. This is evidenced by VAS programs in India not extending to

all those in need, but rather covering about half the population and not providing the full dose

proposed (Laxmaiah et al., 2011). Another gap of VAS programs in India is that more than a third

CORRECTING VITAMIN A DEFICIENCY

of mothers of children in need of supplementation reported not being aware of any existing VAS

program, with half stating that the location and time of VAS were inconvenient (Laxmaiah et al.,

2011).

However, there are examples of VAS programs that have had benefits such as that of Faber et al.,

2015, which found that rural children benefited more from the national food fortification

program in terms of vitamin A intake. This suggests that program initiatives do work as long as

they are properly governed.

Beyond programs of VAS to help alleviate VAD, practices that include the engineering of

food to increase their vitamin A content are being devised. One such method is to genetically

modify foods such as mustard oil (Chow, Klein, & Laxminarayan 2010) and ultra-rice (Li, Lam,

Diosady, & Jankowski 2009) which is a local food staple for the poor. Golden rice provides

enough beta-carotene to supply vitamin A in humans (Tang, Qin, Dolnikowski, Russell, &

Grusak 2009). Fortification is a method of intervention conducted by Uchendu & Atinmo, 2012

who used vitamin A fortified bread that significantly reduced VAD.

A study conducted by Awasthi et al., 2013 contradicted later works that found VAS

reduced child mortality by 20-30%. Instead, Awasthi et al., 2013 found only an 11% reduction.

Another article inconsistent with WHO and other data was that of Yakymenko et al., which found

that the effects of lowering VAS levels was more beneficial in young children (12 months and

younger) (2011).

In conjunction with WHO, we to take advantage of their current infrastructure to prevent

VAD and disperse VAS. The novelty of our intervention is a proposed mobile health center

delivery system, which would educate the locals on proper breastfeeding and use preventative

methods to stop VAD through education while giving VAS to those in need.

CORRECTING VITAMIN A DEFICIENCY

In summary, the serious health consequences to VAD include cellular damage, a

compromised immunity, night blindness, conjunctival xerosis, bitot spots, corneal ulceration,

keratomalacia, total blindness and Xerophthalmia. What the research shows is that certain

program interventions have been addressed in the efforts to prevent and halt VAD in rural and

poor communities. However, there are systematic problems in Indias cultural beliefs such as

scheduled castes, scheduled tribes, and other backward classes allowing only certain groups to

receive better health care than others. Another issue exacerbating VAD is Indias federal, state,

and local policies that are hindering those that need VAS by not regulating the distribution of

these supplements. While some of the data was contradictory or inconsistent, the major

consensus of these articles argued in favor of VAS and food fortification and GMOs to help

alleviate VAD in South Asia, India.

IV.

Description of the Population of Interest

The population of interest we decided to focus our research on are preschool-aged

children living in India, the seventh largest country in the world with the second highest

population (Population Reference Bureau, 2014).

Laxmaiah et al. (2011) found illiteracy, low socioeconomic status, occupation and poor

sanitation to be contributors to VAD. Indias literacy rate for those 7 years and older is 72.99%

according to the 2011 India Census. The Economic Times: India reports that 55% of Indias

population is poor as measured by a composite indicator made up of ten markers of education,

health and standard of living achievement levels and only 39.1% of the total population make up

the Indian workforce (2011 India Census). Most of Indias underprivileged sections of society as

recognized by the Indian Constitution belong to a scheduled caste, scheduled tribe or other

CORRECTING VITAMIN A DEFICIENCY

10

backward classes (Laxmaiah et al., 2011). The 2011 India Census reports that 53.1% of Indian

household have no latrine and 48.9% have no drainage. In 2013, The World Bank reported that

68% of Indias population lives in rural areas.

The rationale for focusing on preschool-age children in this area is because almost half of

the worlds micronutrient-deficient population is in India (USAID, 2005). A large proportion of

the worlds malnourished children live in India (Pasricha et al., 2010). It is reported that Bitots

spots, a symptom of vitamin A deficiency, is 13 times more prevalent in children raised in the

scheduled caste and 20 times more prevalent in the children of laborers (Aplappa et al.).

According to the World Health Organization (WHO) (2104), 62% of Indian preschoolaged children are vitamin A deficient, having serum retinol concentrations lower than 20 g/dL,

making vitamin A deficiency a severe public health problem in India. An estimated 600,000

children in India go blind each year due to VAD (USAID, 2005).

V.

Summary

As mentioned earlier in the population section of this proposal, India is the second most

populated country in the world and this particular region holds close to half of the worlds

vitamin A deficient population. For this reason our proposed intervention could be significant in

reducing VAD in India by expanding the access of VAS to rural regions. Vitamin A is vital to the

development of young children, especially their eyes and immune function. VAD is the leading

cause of childhood blindness and is easily prevented with adequate vitamin A intake. The

proposal would help improve the health status of the population of interest by applying mobile

health centers to supply vitamin A and provide education. We estimate a decline in childhood

CORRECTING VITAMIN A DEFICIENCY

11

blindness, reduce xerophthalmia, improve immune function, increase growth, and lessen the risk

of morbidity and mortality

VI.

References

Awasthi, S., Peto, R., Read, S., Clark, S., Pande, V., & Bundy, D. (2013). Vitamin A

supplementation every 6 months with retinol in 1 million pre-school children in north

India: DETVA, a cluster-randomized trial. Lancet Elsevier, 381(9876) 1469-1477. doi:

10.1016/S0140-6736(12)62125-4

Census of India. (2011). Census 2011. [Data file]. Retrieved from http://censusindia.gov.in/2011prov-results/data_files/maharastra/6-%20Chapter%20-%203.pdf

Census of India (2011). Economic Activity. Retrieved from

http://censusindia.gov.in/Census_And_You/economic_activity.aspx

Census of India (2011). India Having latrine facility within the premises: Total Households.

Retrieved from

http://www.devinfolive.info/censusinfodashboard/website/index.php/pages/sanitation/tota

l/totallatrine/IND

CORRECTING VITAMIN A DEFICIENCY

12

Census of India (2011). India Literacy rate, 7+ yrs. Retrieved from

http://censusindia.gov.in/2011census/censusinfodashboard/index.html

Census of India (2011). India Type of waste water outlet connected to: No drainage

Households. Retrieved from

http://www.devinfolive.info/censusinfodashboard/website/index.php/pages/sanitation/tota

l/nodrainage/IND

Chow, J., Klien, Y. E., & Laxminarayan, R. (2010, August 10). Cost-Effectiveness of Golden

Mustard for Treating Vitamin A Deficiency in India. PLoS ONE 5(8): e12046. doi:

10.1371/journal.pone.0012046. http://www.plosone.org/article/fetchObject.action?

uri=info:doi/10.1371/journal.pone.0012046&representation=PDF

Faber, M., van Jaarsveld, P. J., Kunneke, E., Kruger, H. S., Schoeman, S. E., & van Stuijvenberg,

M. E. Vitamin A and anthropometric status of South African preschool children from four

areas with known distinct eating patterns. Elsevier 31(1), 64-71. http://ac.elscdn.com/S0899900714002160/1-s2.0-S0899900714002160-main.pdf?_tid=78b11f80c3af-11e4-a36e00000aab0f27&acdnat=1425612094_32394da85a8c9ccb9ac09bd62c3c3385

Gebremedhin, S. (2014). Effect of a single high dose vitamin A supplementation on the

hemoglobin status of children aged 6-59 months: propensity score matched retrospective

cohort study based on the data of Ethiopian Demographic and Health Survey 2011. BMC

Pediatrics 14(79), 1-8. doi: 10.1186/1471-2431-14-79

Laxmaiah, A., Nair, M. K., Arlappa, N., Raghu, P., Balakrishna, N., Rao, K. M., Galreddy, C.,

Kumar, S., Ravindranath, M., Rao, V. V., & Brahmam, G. N. V. (2011). Prevalence of

CORRECTING VITAMIN A DEFICIENCY

13

ocular signs and subclinical vitamin A deficiency. Public Health Nutrition, 15(4), 568577. doi: 10.1017/S136898001100214X

Li, Y. O., Lam, J., Diosady L. L., & Jankowski, S. (2009). Antioxidant system for the

preservation of vitamin A in Ultra Rice. Food and Nutrition Bulletin 30(1), 82-89.

http://www.ingentaconnect.com/content/nsinf/fnb/2009/00000030/00000001/art00009

Osei, A. K., Rosenberg, I. H., Houser, R. F., Bulusu, S., Mathews, M., & Hamer, D. H. (2010).

Community-Level Micronutrient Fortification of School Lunch Meals Improved Vitamin

A, Folate, and Iron Status of Schoolchildren in Himalayan Villages of India. The Journal

of Nutrition, 140 (6), 1146-1154. doi: 10.3945/jn.109.114751

Semba, R. D., Saskia, D. P., Sun, K., Bloem, M. W., & Raju, V. K. (2010). The Role of Expanded

Coverage of the National Vitamin A Program in Preventing Morbidity and Mortality

among Preschool Children in India. The Journal of Nutrition, 8, 208S-212S. doi:

10.3945/jn.109.110700. http://jn.nutrition.org/content/140/1/208S.full.pdf

Shrinivassan, R. (2010, July 15). 55% of Indias population poor: Report. The Economic Times:

India. Retrieved from http://articles.economictimes.indiatimes.com/2010-0715/news/27599998_1_child-mortality-nutrition-oxford-poverty

Tang, G., Qin, J., Dolinkowski, G. G., Russell, R. M., & Grusak, M. A. (2009). Golden Rice is an

effective source of vitamin A. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 89(6), 17761783. http://ajcn.nutrition.org/content/89/6/1776.full.pdf+html

Uchendu, F., & Atinmo T. (2012). Nigerian Bread Contribute One Half of Recommended

Vitamin a Intake in Poor-Urban Lagosian Preschoolers. International Journal of Social,

Education, Economics and Management Engineering, 6(10), 405-410.

CORRECTING VITAMIN A DEFICIENCY

14

http://waset.org/publications/7032/nigerian-bread-contribute-one-half-of-recommendedvitamin-a-intake-in-poor-urban-lagosian-preschoolers

U.S. Agency for International Development. (1996). OMNI Micronutrient Facts: India [Data

file]. Retrieved from http://pdf.usaid.gov/pdf_docs/pnacg701.pdf

World Health Organization. (2007). WHO Global Database on Vitamin A Deficiency: India

[Data file]. Retrieved from

http://who.int/vmnis/vitamina/data/database/countries/ind_vita.pdf

VII.

Appendices:

CORRECTING VITAMIN A DEFICIENCY

15

Você também pode gostar

- Declaration by The CandidateDocumento39 páginasDeclaration by The CandidateAswathy RCAinda não há avaliações

- NUTRITION ESSENTIALS A Guide For Health ManagersDocumento148 páginasNUTRITION ESSENTIALS A Guide For Health ManagersMatias CAAinda não há avaliações

- Ans2 Research Paper Vitamin ADocumento7 páginasAns2 Research Paper Vitamin Aapi-534404025Ainda não há avaliações

- Vitamin A Deficiency: Diverse Causes, Diverse SolutionsDocumento12 páginasVitamin A Deficiency: Diverse Causes, Diverse SolutionsAviolist AugustavaniaAinda não há avaliações

- VAD ProjectDocumento14 páginasVAD ProjectMr DanielAinda não há avaliações

- Materi MandiriDocumento6 páginasMateri Mandirip17311191006 RANINDYA DWI NOVIYANTIAinda não há avaliações

- Thesis On Vitamin A DeficiencyDocumento8 páginasThesis On Vitamin A DeficiencyLisa Garcia100% (1)

- Cabriadas 2r VadDocumento32 páginasCabriadas 2r VadTintin HonraAinda não há avaliações

- Bioscientific Review (BSR)Documento14 páginasBioscientific Review (BSR)UMT JournalsAinda não há avaliações

- Chapter Two and Three Project Kadpoly 2021Documento33 páginasChapter Two and Three Project Kadpoly 2021dahiru njiddaAinda não há avaliações

- Association Between Vitamin D Status and Undernutrition Indices in Children - A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Observational StudiesDocumento9 páginasAssociation Between Vitamin D Status and Undernutrition Indices in Children - A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Observational StudiesAnggie DiniayuningrumAinda não há avaliações

- Maternal Nutrition & Dietary Awareness in Rural India - Need For Strong Community Supportive MechanismsDocumento3 páginasMaternal Nutrition & Dietary Awareness in Rural India - Need For Strong Community Supportive MechanismsAhmad Jameel QureshiAinda não há avaliações

- Unveiling The Present Landscape of Malnutrition in India: A Comprehensive AssessmentDocumento5 páginasUnveiling The Present Landscape of Malnutrition in India: A Comprehensive AssessmentIJAR JOURNALAinda não há avaliações

- Chapter 2Documento7 páginasChapter 2Mick MickeyAinda não há avaliações

- Ayesha Ishtiaq BS HND 2021-033 (M) Section BDocumento13 páginasAyesha Ishtiaq BS HND 2021-033 (M) Section BAyesha IshtiaqAinda não há avaliações

- Vitamin K 11 21 16Documento13 páginasVitamin K 11 21 16api-345397204Ainda não há avaliações

- Title Defense: MembersDocumento19 páginasTitle Defense: MembersCharlotteAinda não há avaliações

- StuntingDocumento9 páginasStuntingtasyaAinda não há avaliações

- Chapter TwoDocumento12 páginasChapter TwoMuhd SaniAinda não há avaliações

- A Review of Stunting Growth in Children: Relationship To The Incidence of Dental Caries and Its Handling in ChildrenDocumento6 páginasA Review of Stunting Growth in Children: Relationship To The Incidence of Dental Caries and Its Handling in Childrenenda markusAinda não há avaliações

- CH - RH MergedDocumento753 páginasCH - RH MergedAneela KhanAinda não há avaliações

- ERLINFRISKA 2006505505 TheUtilizationofAndroid-BasedApplicationasaStuntingPreventionDocumento11 páginasERLINFRISKA 2006505505 TheUtilizationofAndroid-BasedApplicationasaStuntingPreventioninidurinidAinda não há avaliações

- Building A Prediction Model FoDocumento9 páginasBuilding A Prediction Model Fosyukrianti syahdaAinda não há avaliações

- Prevalence of Vitamin A Deficiency in South Asia: Causes, Outcomes, and Possible RemediesDocumento11 páginasPrevalence of Vitamin A Deficiency in South Asia: Causes, Outcomes, and Possible RemediesDhimas Ihza MahendraAinda não há avaliações

- MalnutritionDocumento7 páginasMalnutritionapurvaapurva100% (1)

- Ebiomedicine: Research PaperDocumento7 páginasEbiomedicine: Research PaperSri Widia NingsihAinda não há avaliações

- Anaemia Policy BriefDocumento7 páginasAnaemia Policy BriefAini DjunetAinda não há avaliações

- Nutritional Status of Children in India and SDGSDocumento7 páginasNutritional Status of Children in India and SDGSInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyAinda não há avaliações

- Factors Related To Stunting in Toddlers: 1 Indanah Kudus, Indonesia Indanah@umkudus - Ac.id 2 Ratna Dewi J Kudus, IndonesiaDocumento5 páginasFactors Related To Stunting in Toddlers: 1 Indanah Kudus, Indonesia Indanah@umkudus - Ac.id 2 Ratna Dewi J Kudus, Indonesiasitii nurlelaAinda não há avaliações

- Jurnal Defisiensi Vitamin ADocumento16 páginasJurnal Defisiensi Vitamin AAdlia Ulfa SyafiraAinda não há avaliações

- Albumin and Serum Vitamin A Status of Malnourished ChildrenDocumento6 páginasAlbumin and Serum Vitamin A Status of Malnourished ChildrenVidinikusumaAinda não há avaliações

- 782Documento20 páginas782Aarathi raoAinda não há avaliações

- POSHAN Abhiyaan: Fighting Malnutrition in The Time of A PandemicDocumento17 páginasPOSHAN Abhiyaan: Fighting Malnutrition in The Time of A PandemicBijay Kumar MahatoAinda não há avaliações

- Anam Khan - E163Documento13 páginasAnam Khan - E163jacacomarketingAinda não há avaliações

- Who NMH NHD 14.4 EngDocumento8 páginasWho NMH NHD 14.4 EngFahriah AsniarAinda não há avaliações

- Chapter One 1.1 Background To The StudyDocumento33 páginasChapter One 1.1 Background To The StudyTajudeen AdegbenroAinda não há avaliações

- Vitamin-A Deficiency and Its Determinants Among PRDocumento9 páginasVitamin-A Deficiency and Its Determinants Among PRaizah afifaturAinda não há avaliações

- Factors Related To Stunting in Toddlers: 1 Indanah 2 Ratna Dewi JDocumento4 páginasFactors Related To Stunting in Toddlers: 1 Indanah 2 Ratna Dewi Jsanita putriAinda não há avaliações

- 341 Nutrient Deficiency or Disease: Definition/Cut-off ValueDocumento7 páginas341 Nutrient Deficiency or Disease: Definition/Cut-off ValueTariqAinda não há avaliações

- Navigating The Clinical Landscape of Severe Acute Malnutrition in India's Pediatric DemographicDocumento10 páginasNavigating The Clinical Landscape of Severe Acute Malnutrition in India's Pediatric DemographicInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyAinda não há avaliações

- Malnutrition: The Crisis of Malnutrition in IndiaDocumento5 páginasMalnutrition: The Crisis of Malnutrition in IndiaDane PukhomaiAinda não há avaliações

- Micronutrient Program - Department of HealthDocumento3 páginasMicronutrient Program - Department of HealthMelvin MarzanAinda não há avaliações

- Meeting Nutritional Needs Through School FeedingDocumento40 páginasMeeting Nutritional Needs Through School Feedingjmn_0905Ainda não há avaliações

- Vitamin b12 ThesisDocumento4 páginasVitamin b12 ThesisSomeoneToWriteMyPaperForMeNewark100% (3)

- Micronutrient ThesisDocumento4 páginasMicronutrient Thesisabdiqadir ali adanAinda não há avaliações

- Chapter: OneDocumento44 páginasChapter: OneCare 101Ainda não há avaliações

- Children 10 00695Documento16 páginasChildren 10 00695BBD BBDAinda não há avaliações

- The Causes and Effect of Maknutrition Among Children at Tudun Wada in Makarfi Local Government Area of Kaduna State.Documento47 páginasThe Causes and Effect of Maknutrition Among Children at Tudun Wada in Makarfi Local Government Area of Kaduna State.YUSUF AMINUAinda não há avaliações

- Who NMH NHD 14.3 EngDocumento12 páginasWho NMH NHD 14.3 EngHanny Hernadha Putri DharmawanAinda não há avaliações

- WHO NMH NHD 14.3 EngDocumento14 páginasWHO NMH NHD 14.3 EngizzaaaaawAinda não há avaliações

- Ijret20140306114 PDFDocumento7 páginasIjret20140306114 PDFYolanda SimamoraAinda não há avaliações

- Berger. Et - Al 2008Documento8 páginasBerger. Et - Al 2008Trianto Budi UtamaAinda não há avaliações

- 543-Original Article-3692-1-10-20211219 - TerbitDocumento11 páginas543-Original Article-3692-1-10-20211219 - TerbitAtik PramestiAinda não há avaliações

- Strengthening Peer Educator On Mother's Knowledge and Attitudes of Stunting in Ogan Komering Ilir RegencyDocumento7 páginasStrengthening Peer Educator On Mother's Knowledge and Attitudes of Stunting in Ogan Komering Ilir RegencyIts4peopleAinda não há avaliações

- The Global Alliance For Vitamin A (GAVA) : Strategic Plan 2016-2020Documento20 páginasThe Global Alliance For Vitamin A (GAVA) : Strategic Plan 2016-2020MohammedAinda não há avaliações

- Akhtar S Et Al., 2013. Micronutrient Deficiencies in South AsiaDocumento8 páginasAkhtar S Et Al., 2013. Micronutrient Deficiencies in South AsiaAtulAinda não há avaliações

- Monica Ironsuppl FrontiersDocumento10 páginasMonica Ironsuppl FrontiersPia GayyaAinda não há avaliações

- Micronutrient Status of Indian Population.7Documento11 páginasMicronutrient Status of Indian Population.7Nishita SuratkalAinda não há avaliações

- User's Guide to Eye Health Supplements: Learn All about the Nutritional Supplements That Can Save Your VisionNo EverandUser's Guide to Eye Health Supplements: Learn All about the Nutritional Supplements That Can Save Your VisionNota: 5 de 5 estrelas5/5 (1)

- Breastfeeding and vitamin D supplementation: Do you need it?No EverandBreastfeeding and vitamin D supplementation: Do you need it?Ainda não há avaliações

- Theodore Henry Shackleford - My Country and Other PoemsDocumento246 páginasTheodore Henry Shackleford - My Country and Other Poemschyoung0% (1)

- Fruit Logistica Trend Report 2018 Part1Documento19 páginasFruit Logistica Trend Report 2018 Part1Jesu Gajardo OrósticaAinda não há avaliações

- Transcript of Let's Master English's Podcast Episode 1 PDFDocumento4 páginasTranscript of Let's Master English's Podcast Episode 1 PDFJulieta VillanuevaAinda não há avaliações

- Action Plan Gift GivingDocumento5 páginasAction Plan Gift GivingAnnie Lyn De ErioAinda não há avaliações

- Tutorial Wedge Shoe Cake by Sugar & Spice CakesDocumento51 páginasTutorial Wedge Shoe Cake by Sugar & Spice Cakesacdnadmin75% (4)

- Past Perfect Tense Past Perfect Continuous 3Documento4 páginasPast Perfect Tense Past Perfect Continuous 3Mau Diaz0% (1)

- TerrestrialDocumento19 páginasTerrestrialdebanjanr262Ainda não há avaliações

- Avocado Oil Refined Tx008222 PdsDocumento3 páginasAvocado Oil Refined Tx008222 Pdskwamina20Ainda não há avaliações

- Consumer Perception About Fastfood Centres in AsabaDocumento8 páginasConsumer Perception About Fastfood Centres in AsabaOpia AnthonyAinda não há avaliações

- Study Guide Cookery NC 2Documento7 páginasStudy Guide Cookery NC 2FRANCIS D. SACROAinda não há avaliações

- Budget of WorkDocumento18 páginasBudget of WorkCicille Grace Alajeño CayabyabAinda não há avaliações

- Batna BasicsDocumento43 páginasBatna BasicsPrabina ShakyaAinda não há avaliações

- Snow White and The Seven DwarfsDocumento15 páginasSnow White and The Seven DwarfsLê Đình TrungAinda não há avaliações

- At The Farm 16Documento18 páginasAt The Farm 16api-677034951Ainda não há avaliações

- Bahrain New Regulation For Medical DeviceDocumento2 páginasBahrain New Regulation For Medical Devicegulafsha1Ainda não há avaliações

- 11 - 19, 21-23, 24-25, 27Documento8 páginas11 - 19, 21-23, 24-25, 27Guile PTAinda não há avaliações

- The Vice Busting DIET - Julia HaveyDocumento237 páginasThe Vice Busting DIET - Julia HaveyCristiVlad100% (1)

- Good Gov Social Res. Module 9Documento5 páginasGood Gov Social Res. Module 9Sofia T. OlbesAinda não há avaliações

- Times Leader 12-04-2011Documento88 páginasTimes Leader 12-04-2011The Times LeaderAinda não há avaliações

- 1 2+PATHFI1+HandoutDocumento10 páginas1 2+PATHFI1+HandoutDonna Aizel MagbujosAinda não há avaliações

- Philippine Council For Agriculture and Fisheries Agricultural and Fishery Council ProfileDocumento2 páginasPhilippine Council For Agriculture and Fisheries Agricultural and Fishery Council ProfileRio Vic Aguilar GeronAinda não há avaliações

- The Nether Better Upgrade ManualDocumento24 páginasThe Nether Better Upgrade ManualJosue Mejia100% (1)

- MPUDocumento5 páginasMPU威陈Ainda não há avaliações

- Parent HandbookDocumento24 páginasParent Handbookapi-295769704Ainda não há avaliações

- Section2 1Documento13 páginasSection2 1JessicaAinda não há avaliações

- Egg Layer ProposalDocumento3 páginasEgg Layer ProposalCoronwokers Homebase94% (16)

- Bad Ac Action PlanDocumento5 páginasBad Ac Action PlanCamille Kristine Dionisio100% (7)

- Final Case StudyDocumento18 páginasFinal Case Studyapi-487702467100% (1)

- Manipur State InformationDocumento3 páginasManipur State InformationCHAITANYA SIVAAinda não há avaliações

- Chemistry Project CHIRANJIBIDocumento18 páginasChemistry Project CHIRANJIBIKrìsHna BäskēyAinda não há avaliações