Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

Vester Class Culture Germany Print 2003 42a02

Enviado por

Alex RegisTítulo original

Direitos autorais

Formatos disponíveis

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Vester Class Culture Germany Print 2003 42a02

Enviado por

Alex RegisDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

CLASS AND CULTURE IN GERMANY

Michael Vester

Abstract The article develops a typological map of the class cultures in Germany

(including a short comparison with the typologies of France, Italy and Britain). It is

based on ample qualitative research and representative surveys organised by a

new, dynamic interpretation of the theory of class habitus and social space

developed by Bourdieu. Its methodology centers on Durkheims concept of

milieu which unites the occupational and the cultural dimensions of class. Social

classes are defined primarily not as aggregates of the official employment statistics

but as aggregates of social action, i. e. as groups united and distinguished by

common habitus, practices and tastes. However, the class cultures of everyday life

do not translate directly into political or ideological cleavages. The main six

ideological camps of the political field draw their adherents from different, though

neighbouring milieus in distinct zones of social space. As a whole, the research

supports the hypothesis of class differentiation and not of class erosion.

Keywords

Class change, milieu, habitus, political cleavages.

In this article, there will be developed a typological map of class cultures in

Germany. It is based on a series of research projects organised by a new, dynamic

interpretation of the Bourdieu approach to class habitus and social space. In its

methodology, the research centered on Durkheims concept of milieu which unites

the occupational and the cultural dimensions. Social classes were defined

primarily not as the aggregates of the official employment statistics but as

aggregates of social action, i.e. as groups united by a common habitus and the

respective patterns of practice and taste by which they distinguish themselves

from other milieus. According to its habitus type, each milieu follows specific

stra te gi es of the life cour se which also in clu de spe ci fic edu ca ti o nal and

occupational goals and means and, when frustrated, their substitutes.

Thus, occupational positions are not eliminated from structural analysis as

some of the theorists of post-materialism, affluence and classlessness will have it.

Inste ad, it is seen in a di a lec ti cal rela ti on to the so ci al groups prac ti cal

self-definition. As will be shown, this multi-level approach unites the dimensions

in their relations and therefore allows to locate each milieu in a multidimensional

map of the occupational positions (fig. 3) as well as in historical maps which

identify their descendence from older milieus and class cultures (fig. 4), in maps of

the spatial configuration of milieus in society as a whole (fig. 5) and in maps of their

political dispositions (fig. 6).

In this article, the presentation of German research on the dynamics of

milieus is connected with the discussion of three questions:

SOCIOLOGIA, PROBLEMAS E PRTICAS, n. 42, 2003, pp. 25-64

26

Michael Vester

How can the Bourdieu approach be utilized in different national contexts?

How can the Bourdieu approach be related to the issues of social and cultural

change?

If habitus is the pivot of class analysis, how can research on habitus be

methodologically carried out?

The milieu approach, as developed in Germany under the influence of Bourdieu

and of English cultural studies, is only one of the contributions to solve the first

question, concerning the transnational applicability. It seems that none of these

efforts was content to only apply the Bourdieu approach, imitating it as it had

been developed for the study of the apparently rigid class structures of France.

Each of them tried, in interestingly different aspects, to develop, enlarge or modify

Bourdieus approach in order to enhance its capacity to comprise more aspects of

complex, advanced societies.

Michle Lamont, in her study Money, Morals and Man ners, compared four

factions of the French and United States up per middle class, which comprise

10-15 per cent of the population. In her 160 semi-directive interviews in four

regions, she went into the depth of the habitus patterns, using Bourdieu as a

base (1992: 181, 275). Her results suggest revisions of the main models of

human nature currently in use in social sciences, especially the ontological

model of human na ture of Marxist, structuralist and rational choice theories

which assume that humans are essentially mo tivated by utility maximization,

and that because economic resources are more valuable than other resources

they are the main determinant of social action. (1992: 179, 5) Focussing on

different types of symbolic boundaries drawn by middle-class members, she

found that moral boundaries are still very salient at the discursive le vel. In her

view, even Bour di eu un de res ti ma tes mo ral boun da ri es as com pa red to

socio-economic and cultural boundaries. Mike Savage et al. (1992), in Property,

Bu re a u cracy and Cul ture, studi ed three fac ti ons of the same midd le class,

analy zing the life-style sur vey data and ot her data of pu blic-sec tor

professionals, of managers and government bureaucrats and of postmoderns

in parts of the more modern service occupations. Much like Lamont and

contrary to Bourdieu, they also found a non-distinctive group and also

stressed the importance of culture as an in dependent variable concerning class

position and habitus. They also differ from Bourdieus typology of capital as sets

by paying more attention to the organisational assets in middle-class careers

which loose weight and to an increasing fragmentation of the middle classes.

Still another encouragement to widen the scope of the Bourdieu approach

was formulated by Jan Rupp (1995, 1997), in Rethinking Cultural and Economic

Capital, who suggested to pay more attention to the horizontal axis of Bourdieus

social space. In his study on the educational strategies of workers in the Netherlands,

he noted a strong disposition for investments in the childrens cultural capital which

could be explained not only by vertical mobility striving towards petty bourgeois

standards but also by a horizontal movement towards the left or intellectual pole of

social space, towards more personal autonomy and emancipation.

CLASS AND CULTURE IN GERMANY

27

The implications of Rupps study point to the second question, the capacities

of the Bourdieu approach to explain change. Bourdieus own work, especially in

Distinction, mainly concentrates on the static aspects related to the reproduction of

class. Post-materialism, affluence and modern life styles are regarded, but largely

viewed from the perspective how classes change in order to conserve. This

interpretation is evidently connected with Bourdieus concentration on the upper

classes and their petty bourgeois followers, which are, by definition, interested to

defend their own elevated or elevating position. The dominated classes which, as

we will see later, comprise more or less four fifths of the total population, are only

tre a ted in a short chap ter, which hardly dif fe ren ti a tes sub-groups. Here,

Bourdieus argument is mainly that of a sceptic realism, opposed to the naive

intellectual idealisations of working class consciousness and rebellion forwarded

by leftist and orthodox Marxists in the 1970s.

Rupp (1995, 1997), instead, centers on the emancipatory potentials and

dynamics of the skilled working classes, as a development of cultural capital on the

horizontal axis. Here, Rupp also formulates a missing link relating Bourdieus class

analysis to a central field of his research, the sociology of education. This parallels

our own approach (Vester, 1992 and Vester et al., 1993, 2001), which sees class

dynamics in the contradiction of cultural processes on the horizontal axis and

power relations on the vertical axis of social space. The concepts of the axes of social

space can be enlarged, when they are related to the underlying theoretical concepts

of division and labour or differentiation (horizontal axis), of domination and

counter power (vertical axis), of the differentiation of institutional field levels

(third axis) and of time, as the medium of social practice (fourth axis). These

theoretical differentiations which are elaborated elsewhere (Vester et al., 2001,

Vester, 2002) will be treated in this article mainly implicitly, in connection with the

methodology of our research.

The third question is how the naive intellectual schematisms as criticized by

Lamont could be overcome by a methodology of typological habitus analysis.

Following the English culturalists, especially Raymond Williams (1963), E. P.

Thompson (1963) and Stuart Hall (Hall and Jefferson, 1977), it was possible to

develop the necessary hermeneutic methods. Combining it with Bourdieus

approach, we could attempt to redefine the relation between occupation and

habitus types, trying to solve the problems pointed out by the critics of the

employment aggregate approach, especially by Rosemary Crompton (1998).

The steps of milieu research

Our research was carried out in a series of studies since 1987. The basis was laid in a

first, larger project, supported by the Volkswagen Foundation. Designed after the

Bourdieu approach, it combined three levels of analysis. The most important level

was the qualitative analysis of intergenerational change of class habitus in the new

28

Michael Vester

social milieus. Its results, explicated later, supported the thesis that the new life

styles and habitus did not constitute a radical rupture but a relative modification of

the older class habitus identities. To find the causes and conditions of this

modification, it was related first to a separate statistical analysis of occupational

change in Bourdieus multidimensional social space. The data showed a strong

movement towards the left, cultural pole of social space. Was this the cause of

habitus change, as supporters of the employment aggregate approach suggested?

Or was it produced autonomously by the social milieus and movements, as the

theorists of individualization assume? To test this second hypothesis, we made

three regional case studies of the new social movements and their habitus changes.

Our research finally confirmed the hypothesis that the change of class habitus

was not the result of monocausal dynamics, either of occupational change (as

suggested, e.g., by Bell or by Giddens) or of individual self-activity (as suggested

by Beck), but it was influenced by both, in their status of necessary, but not

sufficient causes of societal change.

In order to assess the relative impact of the different forces, we had to develop

research instruments, which could relate these levels systematically for the whole

society. The only approach available to interrelate the societal dimensions was that

of Bourdieu (1992). Among these instruments, explained below, there was a specific

survey instrument, the 44-statement Milieu Indicator developed by the Sinus

Institute in Heidelberg, which promised to explore the main habitus and life-style

types of society (see SPD, 1984). Used in our representative survey, it offered us a

complete typology of milieu or habitus types, their relative size and the distribution

of the important demographic and socio-economic variables in the milieus.

This map of the totality of class milieus, however, cannot be used in an

isolated manner expecting automatic solutions. It had to be treated with care,

keeping in mind the limits of indicators which only indicate something that has to

be studied separately and directly. To avoid the risk to construct statistical artefacts,

we therefore mainly used the milieu indicator as a heuristic instrument, i.e. a tool for

further qualitative research into the milieus and their habitus. In our basic study we

only had studied the small segment of the new or alternative social milieus

going back to the 1968 movements. To explore these possible ten per cent of the total

population, we had to invest the work of about 250 long qualitative interviews,

which had to be interpreted at length to find out the habitus structures of each case.

To fill the other white spaces in the map of milieus, a series of subsequent

research projects was undertaken for which support was not always easy to be

raised. The most important of these projects were a study on the East German

milieus, conducted in the early nineties (Vester et al., 1995), a later study on

workers education (Bremer, 1999) and a study on the milieus addressed to by the

protestant church (Vgele, Bremer and Vester, 2002). In these qualitative studies,

we mainly concentrated on the milieus formerly associated with the working class

milieus and the labour movements and on their upper neighbours, the milieus of

higher education and services. By these, we could cover more or less 60 per cent of

the total population, developing a first typology, which still has to be improved by

further differentiation of sub-groups.

CLASS AND CULTURE IN GERMANY

29

Step by step, a highly dynamic differentiation of the modernizing milieus of

the popular and employee classes was discovered. In the gradual progress of

research, it was also necessary to test and revise the theoretical and methodological

tools. We soon observed that our original maps of social space did not allow a

consistent placing of the milieus of skilled work and their family tree. This was

only possible after a new statistical analysis of these milieus (Vester, 1998) which

helped to overcome the inconsistencies by the improved concept of axes still in use

(Vester et al., 2001). Solving problems of consistency also makes clear that much

work still has to be done to continue exploring the inner differentiation of the

milieus found and also to explore the still missing third of the population, i.e. the

more traditional and conservative milieus in the right part of social space. 1

Research questions and methodology

The basic research project,2 was designed as an empirical test of the hypotheses on the

dissolution of class and class culture, as presented by Ulrich Beck, Anthony Giddens

and post-modern sociology. In its qualitative parts, we concentrated on the new social

movements and milieus which were supposed to exemplify this dissolution by a

habitus of humanistic values beyond class (Offe, 1985). In further steps, we widened

our scope to West German social space as a whole which was analysed with the help of

the national occupational statistics as well as our own representative survey of 1991

and the named subsequent studies and secondary data analyses.

The research questions and the design of the project were following the

multi-level field concept of Bourdieu by first analysing three main fields (habitus

change, occupational change, and the change of social cohesion) separately and

finally integrating these fields. The methodology could not be taken ready-made

from Bourdieu.3 The following short summary may give some impression of the

operational dimensions developed during the research process.

This work is presently organized in a project on the inner differentiation, also by gender, of the

two central family trees of the milieus, the tradition line of skilled work and the tradition line

of the petty bourgeois popular classes (see Vester, 1998; Vester et al., 2001: 55-57).

The project Social structural change and the new socio-political Milieus, carried out at the

University of Hannover from 1988 to 1992, was especially supported by the Volkswagen

Foundation. The study and its methodology are documented in Vester et al., 1993, 2001. East

German society was not included because the German Democratic Republic was not accessable

when the project began in 1988 and, moreover, it constitutes a different variant of social

structure, which we studied in a separate project (Vester et al., 1995).

As shown more completely in our book, we had to develop the specific hermeneutics of typological

habitus analysis (Vester et al., 2001: 215-218, 311-369), the operational criteria of positioning

occupational groups (ib.: 219-221, 373-426) and habitus groups (ib.: 26-64) in social space and an

analysis of the field dynamics of social movements (ib.: 221, 253-279). Also newly developed was

the design of a representative survey combining attitude and socio-statistical variables according to

Bourdieus theory and to the four axes of social space (ib.: 221-250, 427-502).

30

Michael Vester

The main part of the project (point 3. in the synopsis of fig. 1) asked for the

intergenerational habitus or mentality4 change: Was it true that the alternative milieus

and the new social movements represented a new universalist habitus and practice which

was no more linked to particular class milieus?

In our habitus analyses we took the opposite procedural direction as

Bourdieu took. Bourdieu mainly started with the occupational group and then asked

what life style attributes and practices its members preferred. From these, then, he

reached, by interpretation, the habitus patterns. Interviews were mainly used to

exemplify these habitus patterns. This procedural direction certainly contributed to

Bourdieus alleged economic determinism. Our main starting point, instead, were

the attitude patterns themselves which we found by the interpretation of large

samples of non-directive biographical interviews. Only after having found the

habitus type, we asked which occupation, social relations etc. were typical or

not typical for it.

The sample of the new social milieus was recruited according to a specific

scouting procedure in the three selected regions, cho osing people with

distinctive attributes and practices of the life style of the new social milieus (ib.:

328). The sam ple con sis ted of 24 in ter vi ews for the ini ti al non-di rec ti ve

biographical interviews (which had a length up to five hours) and the subsequent

220 semi-directive interviews, controlling informally that the five basic fields of

experience were covered (see point 2. 3. in fig. 1). For the detection of habitus change

we interviewed two generations. Considering the gender differences of habitus,

the female half of the sample was interviewed as compared to the mothers and the

male half as compared to the fathers.

The habitus types were reached at according to the syndrome concept. By an

intensive procedure of text interpretation, the schemes of valuation, classification

and action (Bourdieu) and their interrelational structure in a comprehensive

habitus syndrome were extracted. The procedure followed the rules of sequence

analysis, i.e. the hermeneutic interpretation of only a few lines of text at one time by

a selected interpretation group which had to discuss and note all variants of

interpretation. In later stages, special attention was given to the balance of these

patterns according to dimensions like ascetic vs. hedonistic, dominance vs.

partnership (also in gender relations), isolation vs. cohesion, popular vs.

distinctive taste etc. Finally, the single habitus traits found in the interpretation

had to be analyzed as to their syndrome structure: How were the single traits

related, which traits had priorities (or a status of goals) and which traits were

representing competing goals or mere means etc?

Habitus structure can be understood as organized like the ethics of everyday

life, defining which values should come first in social practice (e.g., work before

German sociology is mainly following the terminology of Theodor Geiger, who already in 1932,

in the first panoramic analysis of German social structure and class mentalities, uses the term

mentality which he defines interchangably with habitus (Geiger, 1932: 13-16, 77ff; see also

Rschemeyer, 1958). To avoid misunderstandings, we are generally using the term habitus, in

this article.

31

CLASS AND CULTURE IN GERMANY

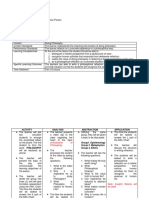

1. Milieus and social practice

2. Occupational structures

3. Habitus and life styles

1.1. Dynamics of cohesion and distinction

in new social milieus

2.1.Reconstruction of the space of social

positions since 1950

3.1.Patterns of social classification in the

new milieus

Exploration of three selected regions

(Hannover, Oberhausen, Reutlingen);

expert interviews, document analyses;

elaboration of milieu biographies: phases

and patterns of development and cohesion

of alternative life style and movement

milieus. 4-12/89; 6/91-2/92

Delimitation of 163 occupational groups

according to Bourdieus capital types; data

collection and catalogization of qualitative

characteristics of each group;

agglomeration and positioning of 102

groups in soc. space; topics and dynamics

of occup. Structure. 9/88-5/89; 9-12/89;

3-6/ 92

Qualitative content analyses of documents

of everyday culture (classification and

valuation patterns in comics by Brsel,

Poth, Fr.Beker, Seyfried, in advertising, in

attributes of the life style etc.); testing the

patterns found in group discussions in

three selected sub-milieus. 9/88 - 3/89

1.2. (= 2.2.) Regional socio-structural change

Expert interviews; collection of data and documents; analysis of the phases of

socio-economic modernization and the iopening of social space since 1950;

comparison of regional development problems of de-industrialization (Oberhausen),

tertiarisation (Hannover) and industrial modernization (Reutlingen); analysis of local

social and electoral structures. 10 - 12/88; 5 - 8/89; 3 - 8/91

3.2.Habitus syndromes and generational

change

Non-directive biographical interviews in

the 3 regions: sample of 12 women and

men of the new milieus plus 12 parent

interviews of same sex; sequence

analyses and hermeneutic interpretation

of the transcripts concerning persistence

and change of habitus patterns. 3/89-1/90

1.3. Urban quarters and politics

2.3. (= 3.3.) The field of new habitus types

Expert interviews, document collection

and observation concerning attributes,

practices and topologies of everyday

culture and social cohesion of milieus in

selected urban quarters (subsequent

research projects in Hannover)

220 narrative interviews of 2-3 hours focussing on five spheres (work and occupation;

family and partnership; leisure, life style and social relations; views of society and

ideologies; socio-political participation) with members of the new milieus and one

parent of the same sex (plus standardized questionnaire and observation resp.

photographs in the home); interpretation and construction of five habitus types.

1/90 - 5/91

4. Social space as a whole

4.1.Macro-analysis of social space

Proportions, structures and dynamics of social milieus, occupational groups and socio-political camps: representative survey

Socio-political milieus in West Germany: development of the analytical instruments concerning social situations, occupational

positions, habitus, cohesion patterns in their temporal and intergenerational change; June/July 1991 by the Marplan Institute;

basic results; cluster- and factor analyses for the identification of types of habitus, cohesion and socio-political camps;

identification of modernizing zones in social space. 1/1991-7/1992, continued later

4.2. Interpretation of the basic patterns of the topics and dynamics of social space as a whole on the base of all four project parts;

integration in a concept of a pluralised class society (1 - 12/92), published in Vester et al., 1993.

4.3. Towards a completion of the qualitative milieu typology

Using the basic patterns or general map of class milieus as a heuristic tool, the qualitative analyses of habitus types and their

historical tradition lines were completed step by step in subsequent projects on the other zones of social space, especially the

three family trees of the popular classes and of higher Education; in a project on workers ecducation (published in: Bremer 1999)

using the methodologies of focussed narrative interviews (see 2.3.) and the newly developed tool of the group workshop, and in a

project on the protestant church and the social milieus in Lower Saxony (published in: Vgele, Bremer and Vester, 2002).

4.4.Completing a revised version of the macroanalysis of social space

The enlarged typology of milieus and their family trees (see 4.3. and Vester et a. 1993) and a multivariate statistical analysis of the

Meritocratic Employee Milieu (published in Vester et al., 2001) revealed contradictions in the first concept and maps of social

space (see 4.2.). The problems were solved by a revised theoretical definition of the concept of the four axes of social space (see

Vester et al., 2001). A subclustering of the milieus of the initial survey (see 4.1.) was done along these axes and produced a better

compatibility of the qualitative and the survey-based typology of now 20 milieus, grouped in 5 milieu tradition lines (see Vgele,

Bremer and Vester, 2002).

Figure 1

Research project Change of social structure and new social milieus (1988-1992) and its

completion by subsequent research

32

Michael Vester

leisure) and which should come to their right, later. In the milieus of skilled work, e.

g., personal autonomy is the primary goal, but embedded in a context of

dispositions for learning, good work performance, solidarity, mutuality, social

justice etc. By this contextual interpretation the classification of the working classes

by isolated properties can be replaced. These properties, e. g. physical work or

collectivism, which lay at the base of the intellectual myth of the proletariat, are

seen to be traits which do occur under special conditions but are not essential for

class identity. The complete syndrome structures are exemplified in the typological

descriptions, later in this text.

The attitude syndromes were first analysed for each case separately. In a

second step, the individual cases had to be grouped to types according to their

different syndrome structures.5 The cases of our sample could be easily separated

into five habitus syndromes or types of the new social milieus, which could be

easily distinguished by their basic structures. For each of the five types a portrait

was formulated (2001: 331-363). Later, the types could be identified as the youngest

and most radical parts of already existing parent milieus. Most interesting among

these newly discovered types was the Modern Employee Milieu, a descendant of

the Traditional Working Class Milieu, which grew to 8 per cent of the population,

until 2000.

The habitus types of the younger generation were not completely different

from the parent generation, as the individualisation thesis supposes, but variations

of the same basic patterns which. This confirmed our initial hypothesis of a

generational habitus metamorphosis, which had been inspired by the Birmingham

cultural studies (Hall and Jefferson, 1977). To find the generational similarities was

mainly possible because each type could be formulated in rather general terms of

the moral and symbolic meaning and not by the surface attributes and

practices of life style, which expectedly differed between the generations.

The next part of the study (no. 2 in fig. 1) asked for the dynamics of the

occupational field: How was habitus change linked to changes in the occupational and

economic position? And where was this occupational change to be located in the total

occupational change of West Germany? The changes of the occupational field since

1950 were analysed by processing the available occupational data according to the

ascending method of Geiger (1932: 17f) and Bourdieus concept of social space.

Geigers method was designed to avoid a main fallacy of the employment

aggregate approaches. Geiger did not start with the larger occupational categories

but split them into smaller, elementary groups, in order to get more adequate

approximations to the cultural and practical dimensions of occupational groups.

The new groups were less heterogeneous in the specific properties of professional

They were not grouped according to types already existing, e.g. in the typologies of Williams

(1963) or Bourdieu (1992). They were also not grouped according to single traits, e.g.

individualization or post-materialism. Not single statements or attitudes but the interrelation of

the statements, the structure of their syndrome as a whole concept of an everyday ethic (Weber),

allowed to group them together. To find a valid typological structure, a maximum of about

twenty cases was necessary. Additional cases gave little additional information.

CLASS AND CULTURE IN GERMANY

33

situation, income, tradition, organizational status etc. After this, Geiger regrouped

them one by one into larger, more homogeneous units, thus ascending from the

single, elementary group to possible larger units. By analysing 163 occupational

groups this way,6 we could map a selection of important occupational fields,

especially in the sectors of the educational, health, technical and agricultural

occupations also divided by gender cleavages (Vester et al., 2001: 413-422).

The principal result of this part of the study was that, according to the data

since 1950, there was a significant movement from the right to the left pole of social

space. This supported the hypothesis of a historical drift towards more cultural

capital on all vertical levels of society. These findings had important consequences

for the theories of the tertiary knowledge society (Bell, 1973). On the one hand,

these tendencies were strongly represented in the data, showing a rise of tertiary

occupations from about 20 to almost 60 per cent up to 1990. But this growth mainly

remained a horizontal movement which did not basically change the vertical

relations of domination between social classes and also the gender, age and

eth nic clas ses. As a con se quen ce, it could be seen that clas ses, whet her

occupational or cultural, did not erode but only move to the left part of social space.

This implies that social conflict, too, did not disappear but move towards a new

level of class conflict, based on the higher competences and aspirations for

autonomy in the popular milieus.

The third part of the study (point 1 in fig. 1) was dedicated to the logic and

patterns of the change of everyday culture and of political camps: How did the

milieus of the new social movements develop their cohesion and identity since the end

sixties? Case histories in the three regions showed by which logics, especially

dynamics of conflicts and coalitions, the new movements and milieus had

developed in the regional field of socio-political camps.

The main finding of this part of the study was that protest action primarily

did not arise according to a logic of repression, material or moral deprivation or

marginalisation, as the conventional hypotheses will have it. Also, the new

identities were not only linked to occupational change, as the employment

aggregate approach suggests. Almost half of the persons interviewed in the survey

who shared the new, more qualified and modernized occupational profiles did not

share the new habitus dispositions. This supports the hypothesis that habitus change

was due to a more general change in the societal field of forces, i.e. the opening of

social space for hitherto unrealized or unrealizable designs of life (according to the

theory of Merleau-Ponty (1965: 503-508) and to the social and political conflicts

between the generations (see Hall and Jefferson, 1977) since the sixties.

The last part (point 4. in fig. 1) aimed at a synthesis, i.e. the changes of the class

configuration as a whole: How did the dynamics of the different fields, studied separately

in the first parts, correlate? How representative were the selected milieus for social

6

Each group was assessed according to a catalogue of eleven socio-economic properties: size and

change of size since 1950, gender, age, educational and occupational diploma, occupational

position, economic sector, main activity, weekly working time, net income of full and part time

employed, immigrant quotas, incidence of unemployment (ib.: 381).

34

Michael Vester

1. Habitus and politics

Everyday culture (1.1. -1.3.) and

socio-political orientations (1.4.-1.6.)

ANALYTICAL CATEGORIES

NO. & CONTENTS OF QUESTION

INTERROGATION MODEL/TIME (MIN.)

1.1 Habitus (mentality types)

(1) basic attitudes towards everyday culture

aspects (work/leisure motivation,

hedonistic/ascetic preferences, gender and family

relations, technological progress and politics)

milieu indicator, with 44 statements and a four

degree scale of consent and dissent, developed

by, used with permission of and data-processed by

the Sinus institute, Heidelberg (12)

1.2. Social cohesion (styles of gregariousness)

(7) basic attitudes towards social relations with

family, friends and acquaintances

1.3. Leisure practices (places of activities)

(13) frequency and scope of different gregarious,

social, cultural and political leisure actrivities

(social places and circles)

indicator of cohesion, with 39 statements

(developed from the projects qualitative

interviews) and a four degree scale of consent and

dissent (10)

list of 22 items and a scale of six degrees of

activity (6)

1.4. Socio-political camps (political styles)

(12) basic attitudes towards the social and political indicator of political styles, modified by the

project, with 45 statements and a four degree

order (social justice, political participation and

scale of consent and dissent (10)

representation, socio-political cleavages)

1.5. Political participation

(P) degree of interest in specific political issues

(4) party sympathies

(8) vote in 1987 general election

(14) vote in 1990 general election

closed question, five alternatives (0,5) five cards

for party ranking (0,5)

closed qn., nine alternatives (0,5)

closed question, 12 alternatives (0,5)

1.6. Socio-political tradition lines

(15b) trade union membersh.of father

open question (0,5)

2. Social situations and positions

community status - Vergemeinschaftung (2.1.-2.4.) and

societal status - Vergesellschaftung (2.5.-2.6.)

ANALYTICAL CATEGORIES

NO. & CONTENTS OF QUESTION

INTERROGATION MODEL/TIME (MIN.)

2.1. Type of Vergemeinschaftung

(household and family type)

(2) family status

(9) permanent partnership relation

(3) way of living together (with

partner/parents/children/friends/alone)

(L) no. of persons in household

(M) age of the household members

closed question, four alternatives (0,5)

open question (0,5)

closed question, four alternatives (0,5)

2.2. Status in Vergemeinschaftung

(A) gender

(B) age

(16) religious affiliation

(noted by interviewer)

open question (0,5)

closed question, four alternatives (0,5)

2.3. Societal status of partner

(social, cultural, econ. capital)

(10) present occup. status of partner

(11) present or last occup.of partner

closed question, 11 alternatives (0,5)

open question (coded according to occup.

statistics) (0,5)

2.4. Territorial milieu

(region, location, home)

(Q) size of building (no. of homes)

(-) size of location (political)

(-) federal state

(noted by interviewer)

(noted by interviewer)

(noted by interviewer)

2.5. Social status of the interviewed person

(cultural and economic capital)

(C) highest school diploma achieved

(D) highest occ.diploma achieved

(E) present occupational status

(F) present or last occupation

(G) occupational activity field (producing,

transporting, office etc.)

(H) present or last occup.position

(K) resources of living

(O) personal net income (monthly)

(N) household net income (monthly)

closed qn., seven alternatives (0,5)

closed question, six alternatives (0,5)

closed question, 12 alternatives (0,5)

open qn.(coded by occ.statistics) (0,5)

closed question, 17 alternatives (0,5)

(5) school diploma of father/mother

(6) last occupational status of father, mother and

grandfathers

closed question, 7 alternatives (1)

closed question, 26 alternatives resp. additional

question (2)

2.6. Social status of the parent and grand parent

generations

(intergenerational mobility)

Figure 2

open questions (0,5)

open question (1)

closed

closed

closed

closed

Analytical categories and instruments of the representative survey

question, 26 alternatives (1)

qun.for 2 of 10 alternatives (1)

question, 12 alternatives (1)

question, 12 alternatives (1)

CLASS AND CULTURE IN GERMANY

35

structure as a whole? What was their size and location in relation to the other social

milieus? These questions were studied by the representative survey of the 1991

West German population.7

Constructing the multi-dimensional questionnaire according to the Bourdieu

approach (see fig. 2 and Vester et al., 2001: 222-244, 546-557), each interviewed

person could be located on all field levels simultaneously. For each level we could

construct independent maps and then see which types of habitus were related to

which types of occupation, social cohesion, ideological camp etc. (Hall and

Jefferson, 1977). A central prerequisite was to find a possibility to identify the class

milieus by their habitus types. For this we were permitted to use the 44 statement

milieu-indicator developed and validated by the Sinus Institute (ib.: 546-548). This

indicator had been constructed to relate qualitative habitus analysis to habitus

detection by standardized methods. Without such an instrument representative

surveys could not disclose what proportion of the total population belonged to the

habitus types originally found by qualitative interviews (carried out as described

above). Initially, the Sinus Institute had extracted the statements of the indicator

from large numbers of non-directive interviews. It was soon clear that the

multidimensionality of the types did not allow batteries with less than forty

statements. The answers are processed by a special clustering procedure, which fixes

the centers of the clusters in order to reproduce the types in follow-up surveys.

When Sinus developed the indicator around 1982, the validity of the types

was tested by various validation procedures and by applying the indicator to a

so-called calibrating sample, i.e. a sample which before had been typologically

analysed by qualitative interviews. Meanwhile, the indicator has been successfully

applied for samples adding to more than 60.000.

In our own research, we used the indicator mainly as a heuristic tool for two

different purposes. First, it helped to quantify, on a representative level, the milieu

types which we had found by qualitative methods, before. Second it helped to

define the sample for qualitative research in those parts of social space about which

we did not yet have sufficient knowledge. This latter procedure was especially

used in our studies on the target groups of trade union adult education and of the

Protestant church (Bremer, 1999, Vgele et al., 2002).

This also helped us to correct inconsistencies of the Sinus model. In general,

the milieu indicator produces valid distinctions between the different types of

milieus. It is evident that the differences between hedonistic and ascetic milieus are

based on clear qualitative differences of the everyday ethics, which can also be

easily reproduced by statistical procedures. However, there are also milieus and

sub-milieus where the analysis of differences is more complicated. This was

especially the case between certain milieu factions of the Meritocratic Employee

Milieu and the Modern Petty Bourgeois Employee Milieu. Qualitative research

revealed that these sub-factions both believe in social hierarchies, which, however,

7

The interviews were made in June and July of 1991 by the Marplan Institute, with a random

sample of 2.699 German speaking inhabitants of 14 years and older, representative according to

the demographic structure of the 1988 micro census.

36

Michael Vester

for the first group is based on personal work achievement (leistung) and for the

second group is based on hierarchical relations of loyalty. But, in modern German

milieus, hierarchies are not openly legitimated by other than work achievement criteria.

It was, however, possible to find the underlying differences by clustering procedures

splitting the milieus into more homogeneous sub-groups which allowed a re-grouping.8

In our survey, additional dimensions of habitus were explored by three other

item batteries and with questions concerning political and trade union participation

as well as trade union participation of the parent generation (see fig. 2).

From the habitus types we proceeded to the second level, the occupational

field. Thus, we could identify the typical occupational profile of each milieu. It is

important to note that none of these profiles followed the distinctions of the official

statistics, i.e. between production and services, secondary and tertiary sectors, blue

and white collar etc. Instead, according to the data, the occupational profiles of the

milieus rather followed (in a loose but clearly significant relation) the capital

dimensions of Bourdieu. When we locate the milieus in Bourdieus map (fig. 3) we

see that no milieu is exclusively limited to a single occupational aggregate. Instead,

each milieu spreads over a certain zone of social space, which covers occupations

with similar combinations of cultural and economic capital.

Our hypothesis had been that habitus changes might at least in part be related to a

secular increase of educational and cultural capital and in the growth of occupations

requiring high standards of cultural capital, on the horizontal axis of social space. Our

results confirmed this horizontal movement. As already noted, only about one half of

the people who took part in this movement also could be counted as part of the

modernized younger mentality types. This confirms the assumption that the mere growth

of cultural capital and a respective leftward movement of the social position may well be a

necessary cause of modernized habitus. But it is not a sufficient cause. It presumably will

not lead to a more autonomous and less hierarchical habitus when the biographical

conflict, the active sub-cultural struggle for emancipated life-styles is not waged.

As will be summed up at the end of this article, our empirical data confirm

that criticism of the employment aggregate approaches to class analysis, as

discussed especially by Rosemary Crompton (1998), is highly justified and that

the Bourdieu-based milieu approach can help to solve several of these problems.

The field structure of social space

To understand milieu change, it is especially important to understand how the

total map of class milieus or class cultures may be structured. We could show this

by three ways to locate the milieus.

The analysis of the two types, which was made by Gisela Wiebke, is to be found in Vgele et al.,

2002, pp. 338-356, 371-376.

CLASS AND CULTURE IN GERMANY

Figure 3

Location of the milieus in Bourdieus space of occupational positions

37

38

Michael Vester

The first way, shown in fig. 3, is to locate each milieu in Bourdieus social space

according to the occupations of its members. The elliptic lines surround the field

zones in which the majority of each milieu have their occupational position. There is a

certain spreading but also a centre of gravitation in the field. Three of the milieus are

dividing the upper part of space among themselves. One of the milieus is confined to

the lower pole of space. Five of the milieus share the middle. They are highly

differentiated on the horizontal axis, from a shrinking petty bourgeois employee

milieu in the right half to growing Modern Employee Milieus in the left half.

This first map (fig. 3) clearly shows a relative homology between economic

and habitus position. The positions the milieus take in the division of labour are

corresponding to a sort of functional division between the other activities of life as

structured by the habitus. Apparently, life style and habitus, as distinctive signs

and practices by which milieu members are finding a common identity and are

distinguishing themselves from other milieus, are the expression of a field of

structured social relations and tensions which are based on complementary

positions of the milieus.

In the second graph (fig. 4) we have grouped the milieus synoptically

to get her to show the ir his to ri cal tra di ti on li nes as well as the ir in ter nal

differentiation. In the case of the respectable popular classes, the data allow to

show a habitus metamorphosis manifested in a sort of family tree. The tradition

line of skilled work (no. 2. 1. the offsprings of the classical working class) consists

of three generational groups: the vanishing old generation of the Traditional

Working Class, the big, but stagnant middle generation of the Meritocratic

Employee Milieu and the growing younger generation of the Modern Employee

Milieu. This pattern of generational modernization does also show, in different

degrees, in Britain, France, and Italy (annexes A1, A2, A3) for which we have the

Sinus milieu data (see Vester et al., 2001: 34-36, 50-54).

The third graph (fig. 5) is structured not by the occupational positions but by

the habitus types. For this positioning we recurred to the implicit principles of

distinction by which each group delimitates itself from the other groups and which

are described in the next parts of this article. The top is taken by three milieus

around 20 per cent who distinguish themselves from the ordinary or popular

milieus below them by their valuation of higher education and culture and the

competences of taste. Below this line of distinction we find the popular classes

(about 70 per cent) for whom qualified work or a secure and respected social status

is the base of self-respect. Below them, we discover the milieus of the underclass,

with poor education and skills (about 10 per cent). They are less respected also

be ca u se of the ir cul tu ral ha bits adap ted to a si tu a ti on of in se cu rity and

powerlessness. They are below what we may call the line of respectability.

Curiously enough, this vertical proportioning of society (20: 70: 10) supports

what Goldthorpe et al. (1968) found out in the 1960s about one of the images of

society: a strong respectable middle, topped by the rich and powerful and

substratified by the underprivileged.

In the same map, we can also see a horizontal division of three zones

separated by two cleavage lines. A cleavage line of authoritarian status orientation

39

CLASS AND CULTURE IN GERMANY

Vertical class pyramid and its horizontal

differentiation by tradition lines

Differentiation of the tradition lines by sub-groups

resp. generations in West Germany (1982-2000)

1. Dominant Milieus

[subdivisions corresponding to upper service class

(a) and lower service class resp. middle class (b)]

1.1.Tradition line of power and property: milieus of the

economic and state functional lites (c. 10%)

1.1.The Conservative Technocratic Milieus

(.9% - c. 10%)

(a) The Grand Bourgeois Milieu

(b) The Petty Bourgeois Milieu

1.2. Tradition line of Higher Education and Services:

milieus of the humanist and service functional lites

(c. 10%)

1.2.The Liberal Intellectual Milieus

(c. 9% - c. 10%)

(a) The Progressive lite of Higher Learning

(b) The Milieu of the Higher Socio-Cultural Services

1.3. Tradition line of the cultural vanguard (c. 5%)

1.3.The Alternative Milieu (c. 5% - 0%)

The Post-modern Milieu (0% - c. 6%)

2. Milieus of the respectable popular and employee

classes [subdivisions corresponding to generations

(a,b,c)]

2.1.Tradition line of skilled work and practical

intelligence (c. 30%)

2.1.(a) The Traditional Working Class Milieu

(c. 10% - c. 4%)

(b) The Meritocratic Employee Milieu (c. 20% - c. 18%)

(c) The Modern Employee Milieu (0% - c. 8%)

2.2. Tradition line of the petty bourgeois popular

classes

(between 28% and 23%)

2.2.(a) The Petty Bourgeois Employee Milieu

(c. 28% - c. 14%)

(b) The Modern Petty Bourgeois Employee Milieu

(0% - c. 8%)

2.3. Vanguard of youth culture (c. 10%)

2.3. The Hedonist Milieu (c. 10% - c. 12%)

3. Underprivileged popular classes (between 8% and

13%) [subdivisions corresponding to orientation

towards the three respectable popular milieus]

3.The Underprivileged Employee Milieus (a) The Status

Oriented (c. 3%)

(b) The Fatalists (c. 6%)

(c) The Hedonist Rebels (c. 2%)

Figure 4

Tradition lines of class cultures (milieus) in West Germany

Note: The allocation of West German Milieus is based on our own representative Survey of 1991 (Vester et al.,

1993, 2001). The percentage data concerning West Germany were taken from Sinus surveys (SPD, 1984,

Becker et al., 1992, Flaig et al., 1993, Spiegel, 1996, stern, 2000).

delimits the petty bourgeois and conservative groups at the right margin. In the

horizontal middle, we find the milieus for which work is the base of self-reliance

and self-consciousness. At the left margin, the cleavage line of the vanguard separates

the hedonistic or cultural vanguard with its idealistic orientations, distinct from

the balancing realism of the middle.

Finally, the axis of time is shown by the inner differentiation of the tradition

lines. While Bourdieu (1992: 585-619) treated the popular classes in a rather short

and summary way, we found this elaborate differentiation of the popular milieus.

Each tradition line resembles a family tree, the younger branches ma inly

distinguishing themselves from the older by modernised cultural capital and

40

Figure 5

Michael Vester

The map of West German Class Milieus

habitus. (As the younger branches are distinguished by modernized cultural

capital and habitus, they are located a little higher and a little more to the left,

symbolized by a thin diagonal distinction line.) Our synopsis (fig. 4) shows how

this inner differentiation increased in a slow but constant movement, since 1982.

The presentation of the results of the 1991 representative survey could take

advantage of the fact that the Sinus Institute continued to use the milieu indicator

in its surveys which allowed us to adapt our data on the macrological proportions

up to the year of 2000. The readers will notice that the changes are relatively modest

another support of the assumption that milieu change mainly is a long-term

change by generations.

CLASS AND CULTURE IN GERMANY

41

The dominant class milieus: power, property and education

The upper social space is divided into five sub-milieus united culturally in their

distinction from those who have little academic education and are less propertied

and influential. This corresponds with their occupational concentration in the

fields of the larger employers, of higher corporate and public management and of

the professions.

At first sight, the dominant milieus as a whole remind of the service class,

as defined by Goldthorpe (1980). But Goldthorpes employment aggregate

approach which suggests a rather affirmative cultural homogeneity of the service

class cannot differentiate the factions which lie at the roots of the dynamics of change

in the upper milieus.9 Thus, it is certainly not true that the service class is united by the

trust in the employer. Like the research of Savage et al. (1992) on the middle class, our

empirical evidence in principle supports Bourdieus identification of sub-groups as

distinguished by their different strategies of social action. These factionings, which are

essential for political and generational change, cannot be identified by the Goldthorpe

approach, due to its confinement to vertical differences.

On the horizontal axis, we could identify three formations which, in

tendency, correspond to the differences found by Bourdieu and by Savage et al. The

first two of these formations are the tradition lines of power and property and of

higher learning and higher socio-cultural services.

In addition, inside each of the two lines we found an upper and a lower

faction. These are somewhat similar to the findings of Herz (1990) who, in West

Germany too, distinguished an upper and a lower service class by levels of

competence. But there is more to these differences than occupational competence.

Especially, the two upper groups play a culturally hegemonic role for the two lower

groups. Their cultural and social capital has been handed on since many generations

and is the highest in the society. The first of the two hegemonic groups follows the

grand bourgeois tradition, the second group follows the tradition of humanist higher

learning. The two lower groups are less endowed, the first being on the way

downward, the second on the way upward. Below the grand bourgeois faction we

find an aged petty bourgeois faction stemming from medium employers, civil

servants and farmers with outdated endowments of cultural capital. Contrasting with

this is the group we find below the humanist intellectual lite. It is a modern and

relatively dynamic service lite, which made its way upwards from the intellectual

factions of the milieus of skilled workers and employees below them.

9

Analysing the West German service class according to the Goldthorpe approach, Thomas Herz

(1990) started from mainly the same occupational groups as we arrived at. Consequently, the

sizes are rather similar, i.e. between 20 and 23 per cent (Herz, 1990: 234) and between 18 and 20

per cent (Vgele, Bremer and Vester 2002, 275-309). However, Herz remains confined to the

limits of the employment aggregate approach, which cannot give differentiated information

on milieus as action aggregates. He can give only wholesale information on the criteria of

socio-cultural class cohesion, stating as common a high concentration of cultural capital, of

privileges, of intergenerational continuity and of a common cultural identity.

42

Michael Vester

Concerning the career patterns, the Bourdieu criterion of social capital is

very helpful to explain the dimensions of historical class reproduction and class

reconversion as a whole. If we consider the specific dynamics to reach and to

maintain occupational positions, this can be better specified by the asset approach

of Savage et al. (1992) paying specific attention to the organisational resources and

relations in the occupational world.

A third horizontal formation is found at the left margin of space. It is a milieu

of the socio-cultural vanguard which is not simply to be explained by the same

in ter ge ne ra ti o nal ac cu mu la ti ons of cul tu ral, eco no mic, so ci al and/or

organizational capital. As a cultural or political vanguard group, it is a result of the

periodical secession from the core milieus of the top, waged by younger candidates

for symbolic lite functions.

The tradition line of power and property (1. 1.)

The tradition line of the Conservative-Technocratic Milieus (now about 10 per cent)

is united by a habitus of an explicit sense of success, hierarchy and power, of a

distinctive taste and of the exclusivity of their social circles and networks. They are

the milieus of property and of institutional domination. To them belong the

best-established parts of the employers, the professions, of the private and public

managements and administrations, and of science and culture.

Since 1945, the old authoritarian capitalist, state and military upper class factions

of Germany have lost their dominant positions to more modern and democratic

younger factions legitimating their hegemony as an lite of merit, education and

technocratic modernization and by cultivating a political discourse of social

partnership with the employee classes, supporting the new historical compromise of

the institutionalized class conflict (Geiger 1949, Dahrendorf 1957).

The dominant group follows the grand bourgeois tradition of erudite and

tolerant conservatism. According to the data, its members mainly consist of higher

private and public managers, the owners of medium and big enterprises and

members of the most privileged professions (especially in the medical and

jurisprudence sectors). They belong to these groups at least in the third generation.

This implies a long accumulation of social and cultural capital. Thus, the

sub-milieu has one of the highest quotas of cultural capital: 37 per cent have Abitur

(the secondary school diploma attesting the maturity to study at a university), 31

per cent have a university diploma.

In contrast, the dominated petty bourgeois faction of the milieu has

surprisingly modest standards of cultural capital (very near to the survey averages

of 13 percent for Abitur and of 5 per cent for the university diploma). Most of them

completed their educational careers in professional schools and then enter the

career ladders inside private or public managements. This pattern is connected

with specific family traditions. The parents, too, had reached only average

CLASS AND CULTURE IN GERMANY

43

educational diplomas and, like the grandparents, were employers, civil servants

and farmers of the medium level. This petty-bourgeois pattern of medium

resources and sustained career efforts corresponds to a cultural tradition of a rather

strict and less tolerant conservatism. The socio-historic explanation of these

specifics is evident when we consider the age of the milieu members. Two thirds

are over 65, the rest largely over 55 years of age (Wiebke, 2002: 304). This indicates

that the group is largely identical with that faction of the bourgeois class, which was

not able to join the reconversion towards or reinforcement of strategies of education

which the majority of the bourgeois milieus made in the 1960s (see Bourdieu and

Passeron, 1971) and consequently is leaving the historical stage, by and by.

Despite of these differences, the factions are united in their policies of

closure, rarely admitting newcomers and up-starts to their circles. These

policies, in Germany, are implemented mainly by subtle habitus and cultural

selection (Hartmann, 1998), working also as informal access barriers in the

educational system.

The tradition line of higher education and higher services (1. 2.)

The second tradition line distinguishes itself exactly against this power conscious

exclusiveness. Its milieus are not occupying the very highest but the higher

ranks of administration and civil service, of the professions, the cultural, social and

educational sectors and the arts. Being not at the very top, they tend to call

themselves middle class, while Bourdieu defines them as the dominated

faction of the dominating classes.

Opposing the materialism of its rivals, the Liberal-Intellectual Milieu (about

10 per cent) prefers distinction in cultural terms, combined with the assertion that

everybody could achieve higher intellectual standards if he or she only wanted. The

mi li eu le gi ti ma tes it self as an en ligh te ned van guard, respon si ble for the

universalistic values of justice, peace and democracy and for the social and

ecological problems caused by economic progress. Their claim of cultural hegemony

over society is somewhat mediated by benevolent or caritative condescension.

Moreover, there are differences between the two sub-groups of the milieu.

The dominating sub-group, the Progressive Elite of Higher Learning (about 5

per cent) is following older family traditions of humanist orientation. The

grandparents already belonged to the well-educated upper stratum of mainly

professionals, higher civil servants and self-employed. Today, they unite the

ma jo rity of the aca de mic in tel li gent sia in the oc cu pa ti ons of na tural and

engineering as well as the social and cultural sciences, in the sectors of publishing,

the media and advertising and in the pedagogical, psychological and therapeutical

services. As already their grandparents, they have high standards of cultural

capital, i.e. 41 per cent have an Abitur and 23 per cent have a university diploma.

Their litist progressism combines ascetic work ethics with an ethos of high

44

Michael Vester

professional performance and often with very distinctive cultural practices,

expressive self-stylization and a sense for unconventional ways.

The dominated faction is the modernized Milieu of the Higher Socio-Cultural

Services (about 4 per cent). It concentrates in higher administration (often

con nec ted with new in for ma ti on tech no lo gi es), es pe ci ally in pu blic

administration, financial departments and publishing sectors. Women, in addition

to this, often work in advisory, medical-technical and educational occupations. The

milieus cultural capital is high only on the Abitur level (27 per cent) and lower in

university diplomas (11 per cent) as, after school, most of them pass a professional

school before starting a career in their occupation. Most of their parents and

grandparents were skilled blue or white collar workers as well as small employers, i.e.

mainly part of the tradition line of skilled work (2. 1.) with its appreciation for

education. Their way into the upper milieus was facilitated by the expansion of new

qualified occupations in the economy and in the welfare state, after 1950. The heritage

of the skilled workers culture of modesty explains why this milieu keeps a certain

distance to the expressive and distinctive self-stylization of the dominant faction.

The tradition line of the cultural vanguard (1. 3.)

In the early 1990s, the place of the vanguard milieu was still taken by the old

Alter na ti ve Mi li eu charac te ri zed by the life-styles and ide als of the 1968

movements. Its members were mainly academic intellectuals working in the

educational, research and cultural sectors as well as in the medical, therapeutical

and social services, or preparing for these activities as students. They have a high

rate of Abitur diplomas (28 per cent) and a rate of university diplomas which, with

regard to the fact that many are still students, is also high (18 per cent).

Culturally, the group professed the post-materialist values of personal

eman ci pa ti on, in di vi du a lity, aut hen ti city as well as the uni ver sa lis tic or

class-less va lu es in the fi elds of gen der, eth ni city, eco logy, pe a ce and

participatory democracy. Since the early 1980s, when the respective movements

succeeded to form the Green Party, the milieu had found increasing public

acceptance. In turn, the alternative values were practiced in less class-less and

increasingly realistic forms. Many former protesters had reached their tacit

biographical aim to become part of the lites. In this process, the milieu, which in

1991 was already down to 2 per cent, was gradually re-absorbed by its parent

milieu, the progressive lite of higher learning.

Meanwhile, its place has been taken by new and younger vanguard milieu,

the Post-Modern Milieu (about 5 per cent). It combines esthetic vanguardism and a

self-oriented ambition to get to the top of life-style, consumption and social

positions. Mainly, its members are up-starts, often younger than 35, with higher

education and still living as singles. They are students or young academics

working on a medium employee, profession or employer level, preferably in

CLASS AND CULTURE IN GERMANY

45

vanguard occupations of symbolic services, culture, the media, the new technologies,

the arts and architecture, but also younger barristers, accountants and surveyors. (This

composition is very near to the postmoderns found by Savage et al. and partly to the

new petty bourgeoisie described by Bourdieu.) Meanwhile, the dreams of the new

economy have given place to an increasing realism, and the milieu may well be

re-absorbed by its parent-milieus in order to be replaced by the next vanguard.

The respectable popular and employee classes

The difference of the Bourdieu and the milieu approaches, as compared to the

employment aggregate approaches, is especially evident when we turn to the

popular classes. Here, we find a horizontal differentiation between rather static

and traditionalist milieus of employees (which largely consists of the offsprings of

the former small owners), a group of rather dynamic employee milieus combining

the search for education and autonomy with a sense of solidarity (being the

offsprings of the former working class) and, finally, a vanguard of life-style (which

mainly turns out to be a transitional stage of the children of the two other groups.)10

It is important to note that, contrary to the ahistoric myth of proletarian

collectivism, the key value of the new working or employee class is autonomy

which it already was when the working class was made (Thompson, 1968, Vester,

1970) and which it also still is in Britain (Savage, 2000).

Work orientation: the self-reliant labouring classes (2. 1.)

An additional remarkable result, confirmed by our survey data, is that the milieus

of the skilled working class, which historically formed the core of the labour

movement, have not eroded in their numbers or habitus. They keep representing

one third of the population (see fig. 4)11 although they changed their appearance.

Contrary to Beck and Giddens, taking part in the structural change towards more

tertiary and white collar occupations did not mean giving up the basic dispositions

of personal autonomy, ascetic work ethics and mutual help, though increasingly

balanced by a moderate hedonism in the younger generations. Their main groups

are the self-re li ant and skil led blue and whi te-col lar wor kers in mo dern

occupations and a smaller faction of the small owners.

10

11

This is shown below, in the portrait of the woman who reconciled herself with work after a

period of refusal.

Bismarck (1957) named the same percentage for the 1950s, and there are indications for a long

historical duration of this quota.

46

Michael Vester

The value system is opposed to that of the petty bourgeois popular classes

whose central value is social status, derived from hierarchical relations. Instead,

for the milieus of skilled work and practical intelligence, autonomy is the central

value, and it is primarily based on what a person can create independently, by his

or her work and practice. This striking parallel to the diagnosis of Savage (2000) is

well illustrated by the small portraits included in the text.

The other values are more or less derived from this. Education and culture are

seen as an important means to develop personal competences of work, autonomy and

orientation. Different personal achievements of work and learning may legitimate a

certain differentiation or hierarchy in the social order. But this hierarchy of skills does not

legitimate any class domination. Accordingly, natural or power inequalities as well

as deference towards social, religious or political authorities are abhorred. Work

orientation founds a meritocratic sense of equality. The value of a person should

depend on the practical works, independent from gender, ethnic or class belongings.

all in your own responsibility

(A Traditional Worker)

Karl, aged 48, after secondary school and an apprenticeship as a carpenter, works at Volkswagen as a

toolmaker. With his wife, a nurse, he lives in his own house in a small town. They have a son of 25.

Karls father was a carpenter, too, his mother was a housewife.

Going to Volkswagen was not only the financial way to fulfil his youths dream to build

my own hut, here, but also a struggle for autonomy at work. First working in a department with

degrading work and catastrophic emissions, he risked severe personal conflicts to be promoted to

his present working place which is rather good, a surrounding (of workmates) that fits: You

work independently, one is allowed to decide by oneself how it is done and so, is all in your own

responsibility.

In his leisure time, Karl is rather active, as a hobby photographer, going to the theatre, doing

carpenter work in his house, acquiring his yachting certificate. He meets his friends for card playing

but does not like to be a club person: Id rather be independent. However, this does not limit his

political activity, in the trade union and also the Social Democratic Party where he contributes to a

magazine being challenged to activate his talents to write: These are things to keep you going,

mentally, in order to have something different, a very different metier. Karl actively participates in

the courses of workers education, distinguishing himself from the young frustrated workers

interested in nothing, with their assembly line faces. He likes the courses to be well organized

and socially useful, e.g. relating his hobby photographing with the presentation of societal

problems.

Meanwhile, Karl says, I have got myself everything I wanted to have (a house, a sailing boat,

a computer etc.), but always caring that I really earned it, first. At the sametime, he is severely

worried about the unemployment of his son and his wife: There, I dont have a perspective.

Although active in labour politics, he is critical: the trade union is too much a closed bunch,

blocking unfamiliar ideas. (Bremer, 1999: 104-106)

Solidarity is not a value in itself but a necessary con dition of personal au to nomy

which is thought to be dependent on mu tual help and co-operation. It does not

mean collectivism but is following the older tradition of neigbourly help and

emergency ethics (Weber, 1964), which, is manifestly mobilized only on special

occasions and for special cases. If somebody is in distress without being

CLASS AND CULTURE IN GERMANY

47

personally responsible for it, help is the neighbours duty. This principle is also

transferred to the political field. The welfare state should not support any

feather-bedding. But it should help everybody who is in need without be ing

responsible for this situation.

Work and life style are largely structured by a special variant of Weberian

protestant ethic, a rational and realistic method of conducing life. In this variant,

however, work and self-discipline again are not values in themselves, which lead

to the proverbial puritan morosity, but combined with the conviction to be entitled

to enjoy the fruits of the own and common efforts and to receive social justice.

This general value pattern may articulate in many different ways, according

to the field situation. In situations of declassment and humiliation it may motivate

militant collective action. In a situation of occupational change it may motivate

reconversions for new occupational fields by strong educational efforts on a family

level. In a situation of prosperity, personal acquisition may come to the fore.

Historically, the habitus pattern itself may shift the balance of its different traits as

new generations with new formative experiences are developing their own ways.

Our data permit to distinguish three milieus each of which is mainly centered

around a different age cohort.

that I reconciled myself with work

(A Meritocratic and Former Hedonist Employee)

Christiane is aged 43. As her mother, she is an employee in public administration, while her father is

an engineer. After secondary school she hanged around at schools for quite some time, before her

parents (now it is enough) made her go to a training for an office occupation. However, she started

her professional career only after the five years of her first marriage, when she was alone with her

little son. Now, she lives together with her second husband, a dental technician, and her son.

Interest in my occupation has grown by and by as years passed and as family obligations

became less absorbing. She acquired additional education and a more interesting post in her office.

However: It could be a little more responsibility. Consequently she put up with the additional

strain and costs of a correspondence course to prepare for a further advancement. At her age, she is

glad to have found my warm place, that I reconciled myself with work and even find it

interesting. The pragmatic orientation of usefulness is also valid for her interest in adult education.

She prefers purposeful programmes, not chatting clubs where everybody tells what he is doing

and possibly returns home as stupid as he came. She wants to get something into her hand, while

the surrounding does not have to be luxurious.

This all leaves her little time for her leisure activities (photographing, movies, museums and

exhibitions), which she shares with her husband. Material things should not be put to the front

although they are not unimportant. Most important, however, is the reliability of social relations for

which you have to do something not only making use of it unilaterally We have lived to be

there for others. Her present husband is a good and equalitarian partner, still interesting after 12

years, despite different opinions on education.

Political education is important to be informed and to understand articles in the press. But: You

can read much, but it is better to discuss it with others. As already her mother, she is active in the works

council, without considering this as political. Trade unions are indispensable as representatives of

the interests of the employees, but their structures have become too rigid and immobile. Therefore, she