Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

The Use of DDT in Malaria Vector Control

Enviado por

Isis BugiaDireitos autorais

Formatos disponíveis

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

The Use of DDT in Malaria Vector Control

Enviado por

Isis BugiaDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Global Malaria Programme

The use of DDT

in malaria vector control

WHO position statement

World Health Organization, 2011

All rights reserved.

The designations employed and the presentation of the material in this publication do not imply the

expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the World Health Organization concerning the legal

status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its

frontiers or boundaries. Dotted lines on maps represent approximate border lines for which there may

not yet be full agreement.

The mention of specic companies or of certain manufacturers products does not imply that they are

endorsed or recommended by the World Health Organization in preference to others of a similar nature

that are not mentioned. Errors and omissions excepted, the names of proprietary products are distinguished by initial capital letters.

All reasonable precautions have been taken by the World Health Organization to verify the information

contained in this publication. However, the published material is being distributed without warranty of

any kind, either express or implied. The responsibility for the interpretation and use of the material lies

with the reader. In no event shall the World Health Organization be liable for damages arising from its

use. The named authors alone are responsible for the views expressed in this publication.

WHO/HTM/GMP/2011

Global Malaria Programme

THE USE OF DDT

IN MALARIA VECTOR CONTROL

WHO Position Statement

ii THE USE OF DDT IN MALARIA VECTOR CONTROL

CONTENTS

1.

Introduction ......................................................................................

2.

2.1

2.2

2.3

Why is DDT still recommended? ...............................................................

Efcacy and effectiveness of DDT .............................................................

Concerns about the safety of DDT .............................................................

Insecticide resistance and the use of DDT ...................................................

2

2

2

3

3.

The use of DDT in disease vector control .....................................................

4.

Safe and effective use of DDT ..................................................................

Strict conditions to be met when using DDT ................................................

5

5

5.

Achieving sustainable malaria vector control in the context

of the Stockholm Convention ...................................................................

Conclusion .......................................................................................

References and background documents .....................................................

6.

Global Malaria Programme

1.

Introduction

Indoor residual spraying (IRS) is a major intervention for malaria control (1).

There are currently 12 insecticides recommended for IRS, including DDT.

The production and use of DDT are strictly restricted by an international

agreement known as the Stockholm Convention on Persistent Organic Pollutants (2). The Conventions objective is to protect both human health and the

environment from persistent organic pollutants. DDT is one of 12 chemicals

identied as a persistent organic pollutant that the Convention restricts. In

May 2007, 147 countries were parties to the Convention.

The Convention has given an exemption for the production and public health

use of DDT for indoor application to vector-borne diseases, mainly because of

the absence of equally effective and efcient alternatives. WHO actively supports the promotion of chemical safety1 and, together with the United Nations Environment Programme, shares a common commitment to the global

goal of reducing and eventually eliminating the use of DDT while minimizing

the burden of vector-borne diseases.

It is expected that there will be a continued role for DDT in malaria control

until equally cost-effective alternatives are developed. A premature shift to

less effective or more costly alternatives to DDT, without a strengthening of

the capacity (human, technical, nancial) of Member States will not only be

unsustainable, but will also have a negative impact on the disease burden in

endemic countries.

This position statement summarizes the issues surrounding the use of DDT

for vector-control purposes.

1.

World Health Assembly Resolution 50.13. Promotion of chemical safety, with

special attention to persistent organic pollutants, 1997.

THE USE OF DDT IN MALARIA VECTOR CONTROL

2.

Why is DDT still recommended?

2.1

Efcacy and effectiveness of DDT

DDT has several characteristics that are of particular relevance in malaria

vector control. Among the 12 insecticides currently recommended for this intervention, DDT is the one with the longest residual efcacy when sprayed on

walls and ceilings (612 months depending on dosage and nature of substrate).

In similar conditions, other insecticides have a much shorter residual efcacy

(pyrethroids: 36 months; organophosphates and carbamates: 26 months).

Depending on the duration of the transmission season, the use of DDT alternatives might require more than two spray cycles per year, which would be very

difcult (if not impossible) to achieve and sustain in most settings.

DDT has a spatial repellency and an irritant effect on malaria vectors that

strongly limit human-vector contact. Vector mosquitoes that are not directly

killed by DDT are repelled and obliged to feed and rest outdoors, which contributes to effective disease-transmission control.

2.2

Concerns about the safety of DDT

DDT has a low acute toxicity on skin contact, but if swallowed it is more toxicand must be kept out of the reach of children. Because of the chemical stability of DDT, it accumulates in the environment through food chains and in

tissues of exposed organisms, including people living in treated houses. This

has given rise to concern in relation to possible long-term toxicity.

The risks that DDT poses to human health are re-evaluated by WHO whenever

there is significant new scientific information. In 2000, the Joint FAO/WHO

Meeting on Pesticide Residues* undertook a comprehensive re-evaluation of

DDT and its primary metabolites including storage of DDT and its metabolitesin human body fat; the presence of residues in human milk and the potential carcinogenicity; and biochemical and toxicological information including

hormone-modulating effects. While a wide range of effects were reported inlaboratory animals, epidemiological data did not support these findings in

humans.

* World Health Organization (2011). Environmental Health Criteria 241. DDT in Indoor Residual Spraying: Human Health Aspects. World Health Organization, Geneva.

Global Malaria Programme

New information published since 2000 was evaluated by a WHO Expert Consultation held in December 2010. This information included new epidemiological studies, up-to-date reported levels in human milk, and new information

on exposures to DDT occurring as a result of IRS. A detailed exposure assessment was undertaken, including potential exposure to both residents in IRStreated homes as well as to spray operators. The WHO Expert Consultationconcluded that in general, levels of exposure reported in studies were below

levels of concern for human health. In order to ensure that all exposures are

below levels of concern, best application practices must be strictly followed to

protect both residents and workers.

Based on the most recent information, WHO has no reason to change its cur-rent recommendations on the safety of DDT for disease vector control. How-ever, WHOs position on the safety and use of DDT will be revised if new

information on the potential hazards of DDT becomes available justifying such

a revision.

2.3

Insecticide resistance and the use of DDT

Only insecticides to which vectors are susceptible (including DDT) should be

used for IRS. Insecticide resistance in malaria vectors has commonly resulted

from the use of the same insecticides for crop protection. In certain settings,

products sprayed on crops contaminate malaria vector breeding sites. This

direct exposure has resulted in the development of vector resistance in several parts of the world. Despite decades of widespread and intensive application, signicant levels of DDT resistance in malaria vectors have been limited

to some vector species and geographical areas. Since DDT use is restricted

to public health activities, vector populations are no longer exposed to DDT

through other applications, which further reduces prospects for selection and

spread of vector resistance.

Effective management of insecticide resistance entails the use of several unrelated insecticides in combination or rotation. The 12 insecticides recommended for IRS belong to only four chemical groups, and DDT represents one

group by itself. Given the very limited arsenal of recommended insecticides,

it is advisable to retain DDT for resistance management until suitable alternatives are available.

THE USE OF DDT IN MALARIA VECTOR CONTROL

3.

The use of DDT in disease vector control

In high-transmission areas, such as in most parts of sub-Saharan Africa, IRS

and insecticide-treated nets are the most effective interventions to control

malaria. When transmission and prevalence of the parasites have been substantially reduced through these two interventions, alternative measures can

increasingly contribute in the context of integrated vector management.

WHO recommends DDT only for indoor residual spraying. Countries can use DDT for as long as necessary, in the quantity needed,

provided that the guidelines and recommendations of WHO and

the Stockholm Convention are all met, and until locally appropriate and cost-effective alternatives are available for a sustainable

transition from DDT. At its third meeting in May 2007, the Conference of the Parties of the Stockholm Convention concluded that

there is a continued need for use of DDT in disease vector control.

This need will be evaluated every two years.

Many malaria-endemic countries have replaced DDT with alternative insecticides, mostly pyrethroids. In some instances this change has compromised

the efcacy of vector-control programmes. For instance, in South Africa the

switch from DDT to pyrethroids in 1997 soon resulted in the reappearance of

Anopheles funestus, a major malaria vector, eliminated from the country for

decades and found to be resistant to pyrethroids. This reappearance resulted

in severe malaria outbreaks, which justied reintroduction of DDT in 2000.

This situation raised awareness of the risks associated with insecticide resistance and potential danger of eliminating DDT too early. Subsequently, several

countries in Africa have introduced, or are planning to reintroduce, DDT in IRS

operations.

Global Malaria Programme

4.

Safe and effective use of DDT

DDT should be used under strict control and only for the intended purpose,

according to a WHO position statement on IRS (1). Using it in any other way

would have important consequences, such as the contamination of food and

agricultural products, including export goods, with a potential impact on international trade. Effective use and safe storage of DDT rely on compliance with

well-established and well-enforced rules and regulations in accordance with

national guidelines and with WHO technical guidance. This should be within

the context of the Stockholm Convention.

There are strict conditions to be met when using DDT and they are described

below.

(i) As DDT is one of the 12 insecticides recommended by WHO for

IRS, the prerequisites for safe and effective implementation of IRS

(1) apply to DDT, including susceptibility status of vectors and

proper monitoring of insecticide resistance to implement resistance-management tactics.

(ii) The use of DDT for IRS must be closely monitored and reported to

WHO and to the Secretariat of the Stockholm Convention2.

(iii) To avoid undue exposure of householders and spray operators

to DDT, standard operating procedures and national guidelines

should be in place and strictly followed. Appropriate management

of DDT also entails adoption and enforcement of stringent rules

and regulations to avoid leakage (into e.g. agriculture) and misuse

(when used in, e.g., domestic hygiene). This includes the possibility of appropriate legal measures in the event that individuals

or entities do not comply with this condition.

(iv) To complement the continued review of information on DDT safety

by the International Programme on Chemical Safety, there is a need

to establish and implement appropriate monitoring strategies to

better characterize DDT exposure (to humans and the environment) under the operational conditions in which DDT is used for

vector control.

2.

Stockholm Convention on Persistent Organic Pollutants, Annex B, paragraph 4.

THE USE OF DDT IN MALARIA VECTOR CONTROL

(v) The status of insecticide resistance, including to DDT, must be

continuously monitored in order to (a) select insecticides to which

vectors are susceptible and (b) implement resistance-management tactics, such as rotation of unrelated insecticides.

(vi) The continued need for DDT should be evaluated regularly by the

parties to the Stockholm Convention and reports made to WHO

and the Secretariat of the Stockholm Convention3. The results

from these evaluations will depend, among other things, on: insecticide resistance status of local vectors; availability of alternative insecticides; control methods and strategies; and level of

funding allocated to malaria vector control.

2.

Stockholm Convention on Persistent Organic Pollutants, Annex B, paragraph 6.

Global Malaria Programme

5.

Achieving sustainable malaria vector control

in the context of the Stockholm Convention

To improve the cost-effectiveness, ecological soundness and sustainability of

vector control, a global strategic framework for integrated vector management

(IVM) has been developed (4). IVM involves the use of proven vector-control

methods, separately or in combination, tailored according to knowledge of

local determinants of disease, including vector ecology, disease epidemiology and human behaviour. IVM is based on the premise that effective control

requires the collaboration of actors within the health sector itself and their collaboration with other sectors, and the engagement of local communities and

other stakeholders.

IRS, including DDT, should be used as a component of an IVM strategy. This

ensures that options for control of local malaria vectors are determined by a

sound understanding of local eco-epidemiological conditions, and are appropriate and effective. IVM creates opportunities to generate synergies between

different vector-borne disease-control programmes: a single intervention can

control more than one vector-borne disease, such as malaria, leishmaniasis or

lymphatic lariasis, that is transmitted by indoor resting vectors.

Alternative insecticides or alternative vector-control strategies and methods of

equivalent efcacy will have to be developed to reduce reliance on DDT. The

rst step is the development of new formulation technologies to increase residual life of existing insecticides to a level equivalent to that of DDT. Additionally, it will be essential to develop new insecticides or active molecules that will

replace DDT, as soon as possible, and that will respond to the challenges of

pyrethroid resistance. These steps require a sustained and high level of effort

and resource mobilization in the context of public-private partnerships. DDT is

still needed today because investment to develop alternatives over the past 30

years has been grossly inadequate.

Non-chemical vector-control methods, such as environmental management or

improvement of house construction (e.g. window screens), should be actively

promoted. Additionally, greater resources should be allocated to research and

development in such methods.

THE USE OF DDT IN MALARIA VECTOR CONTROL

6.

Conclusion

DDT is still needed and used for disease vector control simply because there is

no alternative of both equivalent efcacy and operational feasibility, especially

for high-transmission areas. The reduction and ultimate elimination of the use

of DDT for public health must be supported technically and nancially. It is

essential that adequate resources and technical support are rapidly allocated

to countries so that they can adopt appropriate measures for sound management of pesticides in general and of DDT in particular. There is also an urgent

need to develop alternative products and methods, not only to reduce reliance

on DDT and to achieve its ultimate elimination, but also to sustain effective

malaria vector control.

Global Malaria Programme

References and background documents

1.

Indoor residual spraying: use of indoor residual spraying for scaling up global malaria control

and elimination. Geneva, World Health Organization, 2006 (WHO/HTM/MAL/2006.1112).

2.

Stockholm Convention on persistent organic pollutants. New York, NY, United Nations Environment Programme, 2001 (http://www.pops.int/documents/convtext/convtext_en.pdf, accessed 20 July 2007).

3.

Pesticide residues in food 2000: DDT (para,para-Dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane) (addendum) (http://www.inchem.org/documents/jmpr/jmpmono/v00pr03.htm, accessed 20 July

2007).

4.

Global strategic framework for integrated vector management. Geneva, World Health Organization, 2004 (WHO/CDS/CPE/PVC/2004.10).

5.

Najera J A, Zaim M. Malaria vector control: insecticides for indoor residual spraying. Geneva,

World Health Organization, 2001 (WHO/CDS/WHOPES/2001.3).

6.

Manual for indoor residual spraying: application of residual sprays for vector control. Geneva, World Health Organization, 2002 (WHO/CDS/WHOPES/GCDPP/2000.3/Rev.1).

For further information, please contact:

Global Malaria Programme

World Health Organization

20. avenue Appia CH-1211 Geneva 27

infogmp@who.int

www.who.int/malaria

Você também pode gostar

- The Biology of HomosexualityDocumento201 páginasThe Biology of HomosexualityIsis Bugia100% (1)

- An Overview of Chinas Fruit and Vegetables IndustryDocumento50 páginasAn Overview of Chinas Fruit and Vegetables IndustryAnonymous 45z6m4eE7pAinda não há avaliações

- Fertigation of TurmericDocumento37 páginasFertigation of TurmerictellashokAinda não há avaliações

- Vector-Borne Disease Management ProgrammesDocumento44 páginasVector-Borne Disease Management ProgrammesInternational Association of Oil and Gas Producers100% (1)

- Fundamentals of Agricultural Engineering PDFDocumento2 páginasFundamentals of Agricultural Engineering PDFpohza83% (6)

- Introduction To Agriculture: Esther S.lancitaDocumento25 páginasIntroduction To Agriculture: Esther S.lancitaEsther Suan-Lancita100% (1)

- International Code of Conduct on Pesticide Management: Guidelines on Good Labelling Practice for Pesticides (Revised) August 2015No EverandInternational Code of Conduct on Pesticide Management: Guidelines on Good Labelling Practice for Pesticides (Revised) August 2015Ainda não há avaliações

- Multiple Choice - Exam - Irrigation - 09 - 10Documento9 páginasMultiple Choice - Exam - Irrigation - 09 - 10Gemechu100% (1)

- Zuidberg Frontline Systems BV - Pricelist Valid From 01-01-2012Documento143 páginasZuidberg Frontline Systems BV - Pricelist Valid From 01-01-2012emmanolanAinda não há avaliações

- A Micropropagation System For Cloning of Hemp (Cannabis Sativa L.) by Shoot Tip CultureDocumento6 páginasA Micropropagation System For Cloning of Hemp (Cannabis Sativa L.) by Shoot Tip CultureFco Javier Navarta PiquetAinda não há avaliações

- Guidelines for Personal Protection When Handling and Applying Pesticides: International Code of Conduct on Pesticide ManagementNo EverandGuidelines for Personal Protection When Handling and Applying Pesticides: International Code of Conduct on Pesticide ManagementAinda não há avaliações

- Biodiesel From Micro AlgaeDocumento3 páginasBiodiesel From Micro Algaeraanja2Ainda não há avaliações

- He PhaseDocumento1 páginaHe PhasenimrguwahatiAinda não há avaliações

- Study of DDT (G6) PDFDocumento15 páginasStudy of DDT (G6) PDFNajihah JaffarAinda não há avaliações

- DDTDocumento2 páginasDDTManoloAinda não há avaliações

- Global Surveillance of DDT and Dde Levels in Human Tissues: Kushik Jaga and Chandrabhan DharmaniDocumento14 páginasGlobal Surveillance of DDT and Dde Levels in Human Tissues: Kushik Jaga and Chandrabhan DharmaniInstituto Pablo JamilkAinda não há avaliações

- Jurnal 4Documento6 páginasJurnal 4Asniar RAinda não há avaliações

- Dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane (DDT) For IndoorDocumento15 páginasDichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane (DDT) For Indoorlilibeth paola duran plataAinda não há avaliações

- Al Amin 2020 PV 13 622Documento15 páginasAl Amin 2020 PV 13 622poonamAinda não há avaliações

- Do You Now Think That DDT Should Have Been Banned or Should Still Be UsedDocumento3 páginasDo You Now Think That DDT Should Have Been Banned or Should Still Be UsedJuan Manuel Herrera NavasAinda não há avaliações

- Journal of Global Antimicrobial ResistanceDocumento9 páginasJournal of Global Antimicrobial ResistancerehanaAinda não há avaliações

- Covid 19 Strategy UpdateDocumento19 páginasCovid 19 Strategy UpdateintellectualpseudoAinda não há avaliações

- Pesticide Residues in FoodsDocumento9 páginasPesticide Residues in FoodsderrickAinda não há avaliações

- 51523-Article Text-161459-1-10-20210120Documento2 páginas51523-Article Text-161459-1-10-20210120Azhar HussainAinda não há avaliações

- Ethical Dilemma Applied in Pesticide DDTDocumento9 páginasEthical Dilemma Applied in Pesticide DDTichablubsAinda não há avaliações

- 0902 Reversion Fo ResistranceDocumento3 páginas0902 Reversion Fo ResistranceVibhaMalikAinda não há avaliações

- DDT Case StudyDocumento9 páginasDDT Case Studymaheswari.kumar2784Ainda não há avaliações

- Science of The Total EnvironmentDocumento20 páginasScience of The Total EnvironmentharshAinda não há avaliações

- Policy Guidance On Drug-Susceptibility Testing (DST) of Second-Line Antituberculosis DrugsDocumento20 páginasPolicy Guidance On Drug-Susceptibility Testing (DST) of Second-Line Antituberculosis DrugsrehanaAinda não há avaliações

- Public Health in Outbreak of Covid and ManagementDocumento16 páginasPublic Health in Outbreak of Covid and ManagementMuhammad JavedAinda não há avaliações

- Vector 001 To 004Documento4 páginasVector 001 To 004Jin SiclonAinda não há avaliações

- WHO HCWM Policy Paper 2004Documento2 páginasWHO HCWM Policy Paper 2004Heri PermanaAinda não há avaliações

- FDA Guidance DILs and PAGs For Food ContaminationDocumento59 páginasFDA Guidance DILs and PAGs For Food ContaminationDorje PhagmoAinda não há avaliações

- DdtpersuasiveessayDocumento3 páginasDdtpersuasiveessayapi-269169613Ainda não há avaliações

- Implementation and Challenge in Dealing With The BMW Disposal Guidelines and LegislationsDocumento14 páginasImplementation and Challenge in Dealing With The BMW Disposal Guidelines and LegislationsIJAR JOURNALAinda não há avaliações

- Tugas Jurnal 2Documento12 páginasTugas Jurnal 2RahmaAinda não há avaliações

- International Code of Conduct Om Pesticides 2013Documento32 páginasInternational Code of Conduct Om Pesticides 2013Naku MosesAinda não há avaliações

- Effectiveness of The Most Commonly Used Mosquitoes Repellent in Households in Niameycity (Niger)Documento10 páginasEffectiveness of The Most Commonly Used Mosquitoes Repellent in Households in Niameycity (Niger)IJAR JOURNALAinda não há avaliações

- Preprints202307 1828 v1Documento16 páginasPreprints202307 1828 v1Shandana QasimAinda não há avaliações

- Laboratory Biorisk ManagementDocumento18 páginasLaboratory Biorisk ManagementAni IoanaAinda não há avaliações

- Implications of The COVID-19 Pandemic On Eliminating Trachoma As A Public Health ProblemDocumento17 páginasImplications of The COVID-19 Pandemic On Eliminating Trachoma As A Public Health ProblemZahra Kesturi RifandariAinda não há avaliações

- TDR Ide Den 03.1Documento40 páginasTDR Ide Den 03.1fabio.fagundes6986Ainda não há avaliações

- Guide Handling Cytoxic Drugs Related Waste PDFDocumento89 páginasGuide Handling Cytoxic Drugs Related Waste PDFDewi Ratna SariAinda não há avaliações

- Bourguet & Guillemaud Sustainable Agriculture Review 2016-1Documento87 páginasBourguet & Guillemaud Sustainable Agriculture Review 2016-1azhariAinda não há avaliações

- Gens 102 Assignment 2Documento4 páginasGens 102 Assignment 2mirabelle LovethAinda não há avaliações

- Traditional Medicines: An Alternative Preferencial Remedy For Covid-19 ControlDocumento15 páginasTraditional Medicines: An Alternative Preferencial Remedy For Covid-19 ControlMOULIANNA8949Ainda não há avaliações

- Articulo 3Documento9 páginasArticulo 3nataliameloAinda não há avaliações

- ARMSTRONG JW Fruit Fly Disinfestation Strategies Beyond Methyl BromideDocumento14 páginasARMSTRONG JW Fruit Fly Disinfestation Strategies Beyond Methyl BromideDwik RachmantoAinda não há avaliações

- Neglected Tropical Diseases - Progress Towards Addressing The Chronic PandemicDocumento14 páginasNeglected Tropical Diseases - Progress Towards Addressing The Chronic PandemicVivi AlvarezAinda não há avaliações

- Hygiene Response COVID19 V4Documento70 páginasHygiene Response COVID19 V4Mustafa AdelAinda não há avaliações

- JurnalDocumento4 páginasJurnalAnonymous pfHZusnAinda não há avaliações

- Guidelines For PMDT in India - Dec 11 (Final)Documento199 páginasGuidelines For PMDT in India - Dec 11 (Final)manishwceAinda não há avaliações

- Review: David H Molyneux, Lorenzo Savioli, Dirk EngelsDocumento15 páginasReview: David H Molyneux, Lorenzo Savioli, Dirk EngelsYosia KevinAinda não há avaliações

- TELEDERDocumento7 páginasTELEDERSajin AlexanderAinda não há avaliações

- International Journal of Infectious DiseasesDocumento4 páginasInternational Journal of Infectious DiseasesPedro MalikAinda não há avaliações

- Indoor Residual Spray - 5Documento12 páginasIndoor Residual Spray - 5srinivasthAinda não há avaliações

- An Ethical Risk Management Approach For MedicalDocumento9 páginasAn Ethical Risk Management Approach For Medicalpievee27102004Ainda não há avaliações

- Tele 2Documento10 páginasTele 2Sajin AlexanderAinda não há avaliações

- Current Research in Pharmacology and Drug DiscoveryDocumento10 páginasCurrent Research in Pharmacology and Drug Discoverydev darma karinggaAinda não há avaliações

- DTT&MalariaDocumento3 páginasDTT&MalariaAKARSH RAOAinda não há avaliações

- Who Guidelines TB Ro 2019 PDFDocumento104 páginasWho Guidelines TB Ro 2019 PDFrima melliaAinda não há avaliações

- DDTDocumento5 páginasDDThuyarchitect89Ainda não há avaliações

- Covid Strategy Update 13april2020Documento18 páginasCovid Strategy Update 13april2020garuda unriAinda não há avaliações

- From Concept To Action: A United, Holistic and One Health Approach To Respond To The Climate Change CrisisDocumento7 páginasFrom Concept To Action: A United, Holistic and One Health Approach To Respond To The Climate Change CrisisAndrew FincoAinda não há avaliações

- Abdullahi Muhammad Musa PCC AssignmentDocumento2 páginasAbdullahi Muhammad Musa PCC AssignmentAbdullahi Muhammad MusaAinda não há avaliações

- Covid-19 Prevention StrategiesDocumento6 páginasCovid-19 Prevention StrategiesJackson PaulAinda não há avaliações

- Human Health: and PesticidesDocumento26 páginasHuman Health: and PesticidesLaney SommerAinda não há avaliações

- Agreement of Sanitary and Phytosanitary MeasuresDocumento10 páginasAgreement of Sanitary and Phytosanitary MeasuresShazaf KhanAinda não há avaliações

- 2021 New Trend in The Extraction of Pesticides Applying MicroextractionDocumento28 páginas2021 New Trend in The Extraction of Pesticides Applying MicroextractionSITI NUR AFIQAH MAHAZANAinda não há avaliações

- WHO Dengue Guidelines 2013Documento160 páginasWHO Dengue Guidelines 2013Jason MirasolAinda não há avaliações

- How To Wrtie The Perfect Data Analysis EvaluationDocumento1 páginaHow To Wrtie The Perfect Data Analysis EvaluationIsis BugiaAinda não há avaliações

- Melton Transforming Cookbook LabsDocumento11 páginasMelton Transforming Cookbook LabsIsis BugiaAinda não há avaliações

- Structure Based Drug Design - Muya PDFDocumento831 páginasStructure Based Drug Design - Muya PDFIsis BugiaAinda não há avaliações

- Brooker CH 6 SampleDocumento20 páginasBrooker CH 6 SampleIsis BugiaAinda não há avaliações

- Vector Control Saving LivesDocumento13 páginasVector Control Saving LivesIsis BugiaAinda não há avaliações

- ProteinFolding Dynamics - PDFDocumento29 páginasProteinFolding Dynamics - PDFIsis BugiaAinda não há avaliações

- Manual-5 0Documento312 páginasManual-5 0Isis BugiaAinda não há avaliações

- Practica-III-2 - Um Curso Laboratorial em Química Medicinal Introduzindo A Modelagem MolecularDocumento24 páginasPractica-III-2 - Um Curso Laboratorial em Química Medicinal Introduzindo A Modelagem MolecularIsis BugiaAinda não há avaliações

- Tutorial - Molecular Simulation Methods With GromacsDocumento12 páginasTutorial - Molecular Simulation Methods With GromacsIsis BugiaAinda não há avaliações

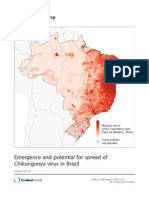

- Emergence and Potential For Spread of Chikungunya Virus in Brazil - FinishedDocumento11 páginasEmergence and Potential For Spread of Chikungunya Virus in Brazil - FinishedIsis BugiaAinda não há avaliações

- (Dufour, Castets,..) Lu. LongipalpisDocumento7 páginas(Dufour, Castets,..) Lu. LongipalpisIsis BugiaAinda não há avaliações

- Visceral Leishmaniasis TreatmentDocumento9 páginasVisceral Leishmaniasis TreatmentIsis BugiaAinda não há avaliações

- FT Baked Beans Tomate Heinz 420gDocumento3 páginasFT Baked Beans Tomate Heinz 420gNuno LeãoAinda não há avaliações

- Of Tribes, Hunters and Barbarians - Forest Dwellers in The Mauryan PeriodDocumento20 páginasOf Tribes, Hunters and Barbarians - Forest Dwellers in The Mauryan PeriodZaheen AkhtarAinda não há avaliações

- FAO Fisheries & Aquaculture - Fishery and Aquaculture Country Profiles - The Republic of GhanaDocumento15 páginasFAO Fisheries & Aquaculture - Fishery and Aquaculture Country Profiles - The Republic of Ghana최두영Ainda não há avaliações

- Kankana Ey SummaryDocumento1 páginaKankana Ey Summarychristian ifurungAinda não há avaliações

- Agricultural Sector in PakistanDocumento4 páginasAgricultural Sector in PakistanimranramdaniAinda não há avaliações

- Classic Cocktails Via ClementDocumento2 páginasClassic Cocktails Via ClementJason McCoolAinda não há avaliações

- Honeybee ProposalDocumento3 páginasHoneybee Proposalapi-284387524Ainda não há avaliações

- ClaydenDocumento52 páginasClaydenapi-194319130Ainda não há avaliações

- The Opportunities of Investing in Costa Rica Farm For Sale1Documento25 páginasThe Opportunities of Investing in Costa Rica Farm For Sale1pinki mollick-17 204 LaptopAinda não há avaliações

- Geo Chapter 4 Class 8 Extra QuestionDocumento6 páginasGeo Chapter 4 Class 8 Extra QuestionJivitesh MangalAinda não há avaliações

- BCS Brochure 2016Documento40 páginasBCS Brochure 2016TractorDiésel100% (1)

- Rural EconomicsDocumento8 páginasRural EconomicssaravananAinda não há avaliações

- History of NasugbuDocumento4 páginasHistory of NasugbuChristian Rey Sandoval DelgadoAinda não há avaliações

- The Imperial Vs The Metric SystemDocumento15 páginasThe Imperial Vs The Metric Systemapi-250910942Ainda não há avaliações

- tmp3397 TMPDocumento7 páginastmp3397 TMPFrontiersAinda não há avaliações

- Final ProposalDocumento29 páginasFinal Proposalgusto koAinda não há avaliações

- Morphology and Life Cycle of Puccinia and The Symptoms of SmutsDocumento21 páginasMorphology and Life Cycle of Puccinia and The Symptoms of SmutsRuchika PokhriyalAinda não há avaliações

- Jess 104Documento14 páginasJess 104ScoutAinda não há avaliações

- Estimating Soil Losses Using Universal Soil Loss Equation (USLE)Documento31 páginasEstimating Soil Losses Using Universal Soil Loss Equation (USLE)Walter F SilvaAinda não há avaliações

- Rice Sector ReportDocumento2 páginasRice Sector ReportHakam DaderAinda não há avaliações

- Chemicals JogiDocumento12 páginasChemicals JoginormanwillowAinda não há avaliações