Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

Ancient Indian Medicine 10

Enviado por

pawansol0 notas0% acharam este documento útil (0 voto)

26 visualizações5 páginasAncient Indian Medicine

Direitos autorais

© © All Rights Reserved

Formatos disponíveis

PDF ou leia online no Scribd

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoAncient Indian Medicine

Direitos autorais:

© All Rights Reserved

Formatos disponíveis

Baixe no formato PDF ou leia online no Scribd

0 notas0% acharam este documento útil (0 voto)

26 visualizações5 páginasAncient Indian Medicine 10

Enviado por

pawansolAncient Indian Medicine

Direitos autorais:

© All Rights Reserved

Formatos disponíveis

Baixe no formato PDF ou leia online no Scribd

Você está na página 1de 5

Ancient Indian Medicine

152

WIM yeaq

qpeap juejsuy

yeep

pue jyooqfoyur Jo ssoy “Teay

quourayioxe — yeyuoUr sosned

SAOGE Se oLeS syNsoy

PeAourar st Joyuyds yr ynsex

ACUI Yyeap osMIAIIO “Tosyt

JO jNO suI0D 0} pamorfe 30

UPCWSr 0} Pamore st royuT|ds

oy} Se BuO] se oyes sy our

‘ujerey paspoy kpoq, usraI0,7

Aint fo 1nsay

peoy 9Y} Jo yorq amt

We POyM-qey om Jo Joasy

oY} Jnoge ye yoour ses ayy

oroyM soovjd oy} ye 100

SH @Aoge pue TNys oy UIETA

jeour afo ayy

pue asou om} ‘Ie9 aM) ‘qynour

oy} Wor savessed imoz oxy

sroya. xuAreyd 043 Jo qpem

Jorraysod pue saddn om) uO

winner

“BID Oy JO sommns cay ony.

80 aq} Jo y00r

at} 38 sMoIq-ofe oy} Toamjog

uonrlod

Arey oy jo AapIog oy) 78

sofdma; oq eroge jods ouL

uoyn207

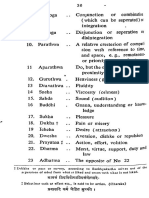

T "W lypues

y ‘Wiupueg

Ss "Wi lqpueg

T W Bg

ZW nkeug

daquinn

P Sapo,

pedpy. “eq

eqewsang “cy

emRWg “TT

medemg ‘or

uredaimn *6

Dudu

ay} {o aun

Surgery in Ancient India 153

Susruta gives detailed instructions as to the sites at which

incisions are to be made in connection with some of the important

marmas. An incision should be made at the spot of a finger’s

width remote from the urvi, kircha-sira, vitapa, kaksa and

parsva-marma ; whereas, a clear space of two fingers from it

should be left in making any incision about the stanamula, mani-

bandha or gulpha-marma. Similarly a space of three fingers

should be left from the Ardaya, vasti, kiarcha, guda or nabhi

marma ; and a space of four fingers from the four sringdtakas,

five simanthas, and ten marmas of the neck ; a space of half a

finger is the rule with the remaining 56. Men versed in the

Science of surgery have laid down the rule that, in a surgical

operation, the situation and dimension of each local marma

should be first taken into, account and the incision made in a

‘way so as not to affect it, inasmuch as an incision which extends

or affects the edge or side of the marma in the least may prove

fatal. Hence all the marma-sthanas should be carefully avoided

in a surgical operation. (S.S. III. 6. 81).

A marma is a junction or meeting place of the five organic

‘structures, that is, of ligaments, blood vessels, muscles, bones and

joints. Susruta thus explains the result of injury to the various

marmas and links it to the tri-dhatu theory. The marmas belong-

ing to the sadya-pranahara group are possessed of fiery virtues ;

as these are easily enfeebled, they prove fatal to life (in the

event of being injured in any way). Those belonging to the

kalantara-pranahara group are fiery and lunar (cool) in their

properties ; and as the fiery virtues are enfeebled easily and the

cooling virtues only after a considerable time, the marmas of

this group prove fatal in the long run (in the event of being

injured in any way), if not instantaneously like the preceding ones.

‘The visalyaghna marmas are possessed of vataja properties (i.e.,

they arrest the escape of the vital vdyu) ; so long as the dart

does not allow the vayu to escape from the injured interior, life

is prolonged ; but as soon as the dart is extricated, the vayu

escapes from inside the injury and this necessarily proves fatal.

‘The vaikalyakaras are possessed of saumya (lunar properties)

and they retain the vital fluid owing to their steady and cooling

virtues ; hence they tend only to deform the organism in the

event of being hurt, instead of bringing on death. The rujakara

marmas of fiery and vataja properties become extremely painful

when injured inasmuch as both of them are pain-generating in

their properties. Others, on the contrary, hold the pain to be

the result of the properties of the five material components of

the body (pancha-bhautika). (S.S. iii 6. 23).

154 Ancient Indian Medicine

But this opinion was not universally held and some authorities

tried to explain the effects of injury on marmas by the varying

composition of the latter. Taking the five varieties of effects,

some assert that marmas, which are the firm union of the above~

mentioned five structures (ligaments, blood vessels, muscles,

bones and joints) belong to the first group (sadya-pranahara) ;

and that those which form the junction of four such, or in which

there is one in smaller quantity, will prove fatal in the long run,

if hurt or injured (Adlantara-pranahara). Those which are the

junction of three such factors belong to the visalya-pranahara

group ; those of two belong to the vaikalyakara group; and

those in which only one exists belong to the pain-generating

type (rujakara). (S.S. iii. 6. 24-25).

There is no mystery about these marmas. From the results

produced by injury it can easily be inferred that they are danger

spots which surgery discovered during operations. They

consist of arteries and veins, nerves, tendons and ligaments, and.

bones and joints. The thoracic and abdominal marmas include

in addition the intestines, the bladder, and the ducts such as the

ureters, seminal vesicles, fallopian tubes, etc. We have seen

that the marmas are divided into 5 distinct groups : fatal in 24.

hours, within a fortnight or a month, as soon as a dart or any

other imbedded foreign matter is extracted, or maiming and

deforming, or painful, according as an injury produced the

aforesaid results. The marmds are arteries, veins, nerves, ten-

dons, and ligaments. A clear knowledge of the anatomy of the

vascular system, the nervous system, the muscles, their origin

and insertions, the ducts and their courses, would have enlighten-

ed the surgeon as to what. artery, vein, nerve or duct he is likely

to meet during the course of his operation. As we have seen,

this knowledge was lacking. Indian physicians since the time

of Susruta were convinced that anatomy securely based on

autopsy dissection is requisite for true medical knowledge. In

Practice, however, Indian anatomy was utterly unable to rise to

the achievement one might have expected from the keen interest

of surgeons in the structure of the human body. “The methodi-

cal dissection of a well preserved corpse after the manner of

modern research and training was excluded bythe tabus of

religion in subtropical’ India. They had to have recourse to the

most unsatisfactory method of dissection which was only possible

under those conditions. The results to be gained by this sort

of gently scrubbing asunder a soaked body on the verge of melting

away, were exactly what one would expect from such an exami-

nation of an object, preserved and decomposing at the same

eo oe Be

Surgery in Ancient India 155

time ; an almost perfect osteology, based on the bony structure

left intact for unlimited inspection ; a fair enumerative know-

ledge of the muscles, sinews and ligaments still sufficiently

preserved ; but no real insight into the intricacies of the nervous

system, the blood vessels, or into the exact course and purpose

cf the various canals and organs essential for metabolism.” *

What anatomy was expected to supply and did not, left no

option to the surgeon but to rely on his own experience. A

knowledge of the anatomy and physiology of the nervous and

vascular systems would have dispelled all the mystery surrounding

the marmas and made the task of the surgeon less hazardous

and dangerous and more certain. The concept of marmas is the

crystallisation of the wide experiences gained by the surgeons of

the dangers and hazards of inadvertently cutting vital structures

like the arteries, veins, nerves, tendons and ligaments. What

anatomy failed to do for him, he out of his own experience

mapped out with his theory of the marmas, the danger spots of

the body. It is this that made the surgery of ancient India

possible and enabled it to attain such an eminent position among

the ancient civilizations.

It has always been a matter of speculation how the ancients

ever carried out major surgery in the absence of anaesthetics,

haemostatics and antiseptics. “Surgical achievements are not

inconsiderable among the primitive people; considering the

paucity of anatomical knowledge, the boldness of operations

undertaken is surprising. Foreign bodies are extracted and ab-

scesses opened with thorns or other sharp pointed gbjects; in

the treatment of wounds suction is employed, sometimes even

a species of drainage by means of sections of bamboo; suture

or tight bandaging, to promote union, is not unknown amongst

some tribes. Stitching of small wounds is carried out by means

._ of thorns, which are used to transfix the edges of the incision,

the ends being then wrapped round. Among some Indian tribes

of Brazil it is customary to allow both edges of a wound to be

seized by the sharp head-nippers of certain ants, whose bodies

are then rapidly cut off; one ant after another: being used, the

wound is closed. In the treatment of ulcers cauterisation with

hot ashes, heated blades and irons are favourite methods. Arrest

of haemorrhage presents great. difficulties to aborigines; for the

most part they do not know how to attack it. It is sometimes

brought about by means of vegetable and mineral styptics, less

often it is attempted by means of circular pressure (tightly bound

bandages). The treatment of dislocations is baséd upon no

rational method, but we have astonishing reports of intelligence

14

156 Ancient Indian Medicine

with which fractures are set. Not only splints (of wood, bark

and bamboo) are employed, but even immobilising apparatus,

made of clay. Of operations the majority concern the sexual

sphere. Circumcision, male and female ; and the Mika opera-

tion (external urethrotomy from the orifice of the glans to the

scrotum, in order to limit the progeny), the Caesarean section and

ovariotomy, have all been performed by the primitive tribes.

“Cupping, blood-letting, in various forms were widespread

methods of treatment. Scarification was performed with thorns.

Venesection was performed upon various veins with splinters of

stone or knives. The instruments used were bone tubes, oxen

or buffalo-horns for cupping, thorns, fish-bones, splinters of

stone, mussel-shells, pieces of bone and glass or knives for scari-

fication, splinters of stone or knives mounted or unmounted were

used for venesection. Trephining and scraping of hollow bones

were undertaken. Intoxication or stupefaction by narcotics and

by hypnotism are the necessary preliminaries for severe measures.

“The not infrequent successful outcome of such operations,

done regardless of all antiseptic precautions, can only be explained

by the supposition that the aboriginal races have a greater power

of resistance against wound infection than highly civilized

nations.

“ Obstetrics, which lies almost exclusively in the hands of the

women, shows a very variable stage of development in different

races; thus among the Malays an attempt is made to rectify

unfavourable positions of the foetus in utero, whilst in Cochin-

China retained placenta is treated by trampling upon the abdo-

men.” $

The above observations on the art of primitive surgery enable

us to understand how the ancient Indians cultivated and perfected

it within their available means and attained a very great profi-

ciency in it. The range of their surgery was not wider than that

of the primitives, but their methods were vastly improved, sup-

plemented by newer knowledge and acquisitions. It is curious

to note that no reference has been made in Indian surgical

treatises to trephining. Susruta classifies surgical operations into

eight different kinds: (1) excision (bhedya); (2) incision

(chhedya) ; (3) scarification (lekhya) ; (4) puncture (vedhya) ;

(5) probing (eshya) ; (6) extraction (Gharya) ; (7) Drainage

or evacuation of fluids (visravya) ; and (8) suturing (sivya).

ASS. I. 5, 4).

A surgeon called upon to perform any of the above operations

should equip himself with such accessories as surgical appliances

-and instruments, viz., blunt instruments, cutting instruments,

Você também pode gostar

- Aadhunik Chikitsashastra 76 To 100Documento25 páginasAadhunik Chikitsashastra 76 To 100pawansolAinda não há avaliações

- Aadhunik Chikitsashastra 50 To 75Documento26 páginasAadhunik Chikitsashastra 50 To 75pawansolAinda não há avaliações

- Pawan Ayurveda Part 1Documento10 páginasPawan Ayurveda Part 1pawansolAinda não há avaliações

- Aayurveda Sikshaa Philosophical BackgroundDocumento12 páginasAayurveda Sikshaa Philosophical BackgroundpawansolAinda não há avaliações

- Regeneration in ManDocumento11 páginasRegeneration in ManpawansolAinda não há avaliações

- Dhanwantri 1Documento14 páginasDhanwantri 1pawansol100% (2)

- Fundamental of Ayurveda OneDocumento10 páginasFundamental of Ayurveda OnepawansolAinda não há avaliações

- A Text Book of Modern Medicine 6Documento14 páginasA Text Book of Modern Medicine 6pawansolAinda não há avaliações

- Fundamental of AyurvedaDocumento10 páginasFundamental of AyurvedapawansolAinda não há avaliações

- A Text Book of Modern Medicine 6Documento14 páginasA Text Book of Modern Medicine 6pawansolAinda não há avaliações

- Regeneration in Man Part 1Documento11 páginasRegeneration in Man Part 1pawansolAinda não há avaliações

- Ancient Indian Medicine 1962Documento14 páginasAncient Indian Medicine 1962pawansol100% (1)

- Dhanwantri 2Documento11 páginasDhanwantri 2pawansol0% (1)

- Textbook of Ayurveda Part 4Documento7 páginasTextbook of Ayurveda Part 4pawansolAinda não há avaliações

- Patanjali Yog DarshanDocumento8 páginasPatanjali Yog DarshanpawansolAinda não há avaliações

- Rogo Ki Achuk Chikitsa 1Documento5 páginasRogo Ki Achuk Chikitsa 1pawansol0% (1)

- Textbook of Ayurveda Part 5Documento7 páginasTextbook of Ayurveda Part 5pawansolAinda não há avaliações

- Textbook of Ayurveda Part 3Documento7 páginasTextbook of Ayurveda Part 3pawansolAinda não há avaliações

- Ancient Indian Medicine 1962Documento5 páginasAncient Indian Medicine 1962pawansolAinda não há avaliações

- Textbook of Ayurveda Part 1Documento7 páginasTextbook of Ayurveda Part 1pawansolAinda não há avaliações

- Dhanwantri 1Documento4 páginasDhanwantri 1pawansolAinda não há avaliações

- Textbook of Ayurveda Part 2Documento7 páginasTextbook of Ayurveda Part 2pawansol100% (1)

- Manav ShariraDocumento4 páginasManav SharirapawansolAinda não há avaliações

- Indian MateriaDocumento4 páginasIndian MateriapawansolAinda não há avaliações

- Swadeshi Chikitsya Part 1Documento107 páginasSwadeshi Chikitsya Part 1rajivdixitmp3.com96% (28)

- Patanjal Yog DarshanamDocumento6 páginasPatanjal Yog DarshanampawansolAinda não há avaliações

- CharakDocumento5 páginasCharakpawansolAinda não há avaliações

- Preparedness of Influenza 14.10.15Documento1 páginaPreparedness of Influenza 14.10.15pawansolAinda não há avaliações

- Patanjal Yog DarshanamDocumento6 páginasPatanjal Yog DarshanampawansolAinda não há avaliações

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeNo EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (5783)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)No EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Nota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (98)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItNo EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (838)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerNo EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (271)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceNo EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (890)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingNo EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (399)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnNo EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (234)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaNo EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (265)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryNo EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (231)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureNo EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (474)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersNo EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (344)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaNo EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (45)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyNo EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (2219)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreNo EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)No EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Nota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (119)