Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

Management Accounting

Enviado por

Al MahmunDireitos autorais

Formatos disponíveis

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Management Accounting

Enviado por

Al MahmunDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Contents

CONTENTS

Chapter 1: Financial accounting review ........................................................................................ 1

1. Framework for Financial Reporting ....................................................................................................................................... 1

2. Structure and content of Financial Statements ................................................................................................................ 3

3. Consolidated Financial Statements......................................................................................................................................20

Chapter 2: Managing Organisation ............................................................................................. 23

1. The Nature of Limited Companies .......................................................................................................................................23

2. Mission, Objectives and Targets ...........................................................................................................................................24

3. Performance Measurement and Performance Management ...................................................................................25

4. Responsibility Centre .................................................................................................................................................................26

5. Cost Accounting and Management Accounting ............................................................................................................29

6. Organisational Structures ........................................................................................................................................................31

7. Divisionalisation, Departmentation and Decentralisation ..........................................................................................32

Chapter 3: Cost Management ....................................................................................................... 35

1. Costing .............................................................................................................................................................................................35

2. Cost classification in the financial statement ..................................................................................................................36

3. Absorption Costing ....................................................................................................................................................................39

4. Activity-Based Costing ..............................................................................................................................................................44

Chapter 4: Managing Budgets ...................................................................................................... 51

1. Purpose and Functions of a Budget ....................................................................................................................................51

2. Process of preparing budget ..................................................................................................................................................54

3. Types of Budget ...........................................................................................................................................................................57

Chapter 5: Breakeven analysis ...................................................................................................... 72

1. The Breakeven Point ..................................................................................................................................................................72

2. Breakeven Graph .........................................................................................................................................................................75

3. Application of CVP and BEP ....................................................................................................................................................78

Chapter 6: Costing Decisions ........................................................................................................ 81

1. Relevant Costs for Decision Making....................................................................................................................................81

2. Cost behaviour and decision making .................................................................................................................................82

3. Limiting factor analysis .............................................................................................................................................................88

4. Make or buy decisions ..............................................................................................................................................................92

5. Decision making under uncertainty ....................................................................................................................................95

Chapter 7: Price Management ...................................................................................................... 97

1. Pricing Policy .................................................................................................................................................................................97

2. Factors affecting the pricing ...................................................................................................................................................97

3. Pricing methods ...........................................................................................................................................................................99

4. Transfer pricing ......................................................................................................................................................................... 105

Chapter 8: Variance Analysis....................................................................................................... 112

1. Types of Variance ..................................................................................................................................................................... 112

Contents

Chapter 9: Quality Management ................................................................................................ 120

1. Measures of shareholder value .......................................................................................................................................... 120

2. Critical success factors and key performance indicators ......................................................................................... 122

3. Balanced scorecard .................................................................................................................................................................. 124

4. Benchmarking ............................................................................................................................................................................ 127

5. Key elements of operations management..................................................................................................................... 130

6. Operational structures and process-based structures .............................................................................................. 130

7. World-class manufacturing and the re-design of operations ............................................................................... 131

8. Materials requirements planning (MRP I) ...................................................................................................................... 138

9. Manufacturing resource planning (MRP II) ................................................................................................................... 140

10. Optimised production technology (OPT) .................................................................................................................... 141

11. Enterprise resource planning (ERP) systems .............................................................................................................. 143

12. Just-in-time production and purchasing ..................................................................................................................... 144

13. Total quality management (TQM) .................................................................................................................................. 150

14. Value for money (VFM) ....................................................................................................................................................... 154

ii

Chapter 1: Financial accounting review

Chapter 1: Financial accounting review

The relationship between Financial Accounting and Management Accounting (also known as

Managerial Accounting) has been described by International Federation of Accountants (IFAC) in

the International Good Practice Guidance: Evaluation and Improving Costing in Organizations.

Figure 1 Financial Accounting and Management Accounting

1. Framework for Financial Reporting

The primary objective of financial reporting is to provide useful information for decision making

by the user. Investors and creditors needs specific cash flow information for making appropriate

business decisions. International Accounting Standards Council (IASC) developed Framework for

the Preparation and Presentation of Financial Statements in 1989 which was adopted by

International Accounting Standards Board (IASB) in 2001. Later on IASB approved Conceptual

Framework for Financial Reporting 2010 which is widely used by the practitioners.

Page | 1

Chapter 1: Financial accounting review

The IFRS Framework describes the basic concepts that underlie the preparation and presentation

of financial statements for external users. The IFRS Framework serves as a guide to the IASB in

developing future IFRSs and as a guide to resolving accounting issues that are not addressed

directly in an International Accounting Standard or International Financial Reporting Standard or

Interpretation.

In addition, the framework may assist:

Preparers of financial statements in applying international standards and in dealing with

topics that have yet to form the subject of an International Accounting Standard

Auditors in forming an opinion as to whether financial statements conform with IASs and

IFRSs

Users of financial statements in interpreting the information contained in financial

statements prepared in conformity with IFRS

Those who are interested in the work of IASB, providing them with information about its

approach to the formulation of accounting standards.

1.1 Purpose and scope of the Framework

The IFRS Framework addresses:

the objective of financial reporting

the qualitative characteristics of useful financial information

the reporting entity

the definition, recognition and measurement of the elements from which financial

statements are constructed

concepts of capital and capital maintenance

1.2 Underlying assumptions

There are two underlying assumptions for the preparation of financial statements, these are:

Accrual Basis

Page | 2

Chapter 1: Financial accounting review

Under the accrual basis, the effects of transactions and other events are recognised when they

occur, and not as cash is received or paid. Under the accruals basis, events are recorded in the

accounting records and reported in the financial statements of the periods to which they relate.

Financial statements prepared on the accrual basis inform users not only to past transactions

when cash was paid or received but also of obligations to pay cash in the future and of cash or

its equivalents to be received in the future.

Going Concern Basis

The going concern basis of accounting is the assumption in preparing the financial statements

that an entity will continue in operation for the foreseeable future and does not plan to go into

liquidation, and will not be forced into liquidation or to curtail its operations.

If such an intention or need exists, the financial statements may have to be prepared on a different

basis and, if so, the basis used is disclosed. The going concern assumption is very important for

the valuation of assets, as they may require valuation on a break-up basis if the company will

cease trading.

2. Structure and content of Financial Statements

IAS 1 Presentation of Financial Statements sets out the overall requirements for financial

statements, including how they should be structured, the minimum requirements for their

content and overriding concepts such as going concern, the accrual basis of accounting and the

current/non-current distinction. The standard requires a complete set of financial statements to

comprise a statement of financial position, a statement of profit or loss and other comprehensive

income, a statement of changes in equity and a statement of cash flows.

A complete set of financial statements includes:

a statement of financial position (balance sheet) at the end of the period

a statement of profit or loss and other comprehensive income for the period

a statement of changes in equity for the period

a statement of cash flows for the period

notes, comprising a summary of significant accounting policies and other explanatory

notes

Page | 3

Chapter 1: Financial accounting review

comparative information prescribed by IFRSs and IASs.

An entity may use titles for the statements other than those stated above. All financial statements

are required to be presented with equal prominence. Reports that are presented outside of the

financial statements including financial reviews by management, environmental reports, and

value added statements are outside the scope of IFRSs.

Financial statements cannot be described as complying with IFRSs unless they comply with all the

requirements of IFRSs (which includes International Financial Reporting Standards, International

Accounting Standards, IFRIC Interpretations and SIC Interpretations).

IAS 1 requires an entity to clearly identify:

the financial statements, which must be distinguished from other information in a

published document

each financial statement and the notes to the financial statements.

In addition, the following information must be displayed prominently, and repeated as necessary:

the name of the reporting entity and any change in the name

whether the financial statements are a group of entities or an individual entity

information about the reporting period

the presentation currency (as defined by IAS 21 The Effects of Changes in Foreign

Exchange Rates)

the level of rounding used (e.g. thousands, millions).

2.1 Statement of financial position (balance sheet)

Current and non-current classification

An entity must normally present a classified statement of financial position, separating current

and non-current assets and liabilities, unless presentation based on liquidity provides information

that is reliable. In either case, if an asset (liability) category combines amounts that will be received

(settled) after 12 months with assets (liabilities) that will be received (settled) within 12 months,

note disclosure is required that separates the longer-term amounts from the 12-month amounts.

IAS 1 classified Current assets as assets that are:

expected to be realised in the entity's normal operating cycle

Page | 4

Chapter 1: Financial accounting review

held primarily for the purpose of trading

expected to be realised within 12 months after the reporting period

cash and cash equivalents (unless restricted).

All other assets are non-current assets.

IAS1 defined Current liabilities as those:

expected to be settled within the entity's normal operating cycle

held for purpose of trading

due to be settled within 12 months

for which the entity does not have an unconditional right to defer settlement beyond 12

months (settlement by the issue of equity instruments does not impact classification).

Other liabilities are non-current liabilities as per IAS1.

When a long-term debt is expected to be refinanced under an existing loan facility, and the entity

has the discretion to do so, the debt is classified as non-current, even if the liability would

otherwise be due within 12 months.

If a liability has become payable on demand because an entity has breached an undertaking

under a long-term loan agreement on or before the reporting date, the liability is current, even

if the lender has agreed, after the reporting date and before the authorisation of the financial

statements for issue, not to demand payment as a consequence of the breach. However, the

liability is classified as non-current if the lender agreed by the reporting date to provide a period

of grace ending at least 12 months after the end of the reporting period, within which the entity

can rectify the breach and during which the lender cannot demand immediate repayment.

Line items of financial statements:

The line items to be included on the face of the statement of financial position are:

i.

property, plant and equipment

ii.

investment property

iii.

intangible assets

iv.

financial assets (excluding amounts shown under (v), (vii), and (ix))

v.

investments accounted for using the equity method

Page | 5

Chapter 1: Financial accounting review

vi.

biological assets

vii.

inventories

viii.

trade and other receivables

ix.

cash and cash equivalents

x.

assets held for sale

xi.

trade and other payables

xii.

provisions

xiii.

financial liabilities (excluding amounts shown under (xi) and (xii))

xiv.

current tax liabilities and current tax assets, as defined in IAS 12

xv.

deferred tax liabilities and deferred tax assets, as defined in IAS 12

xvi.

liabilities included in disposal groups

xvii.

non-controlling interests, presented within equity

xviii.

issued capital and reserves attributable to owners of the parent.

Additional line items, headings and subtotals may be needed to fairly present the entity's financial

position.

When an entity presents subtotals, those subtotals shall be comprised of line items made up of

amounts recognised and measured in accordance with IFRS; be presented and labelled in a clear

and understandable manner; be consistent from period to period; and not be displayed with

more prominence than the required subtotals and totals.

Further sub-classifications of line items presented are made in the statement or in the notes, for

example:

classes of property, plant and equipment

disaggregation of receivables

disaggregation of inventories in accordance with IAS 2 Inventories

disaggregation of provisions into employee benefits and other items

classes of equity and reserves.

2.2 Format of financial statements

IAS 1 does not prescribe the format of the statement of financial position. Assets can be

presented current then non-current, or vice versa, and liabilities and equity can be presented

current then non-current then equity, or vice versa.

Page | 6

Chapter 1: Financial accounting review

A net asset presentation (assets minus liabilities) is allowed.

The long-term financing approach used in UK and elsewhere fixed assets + current assets short term payables = long-term debt plus equity is also acceptable.

Share capital and reserves

Regarding issued share capital and reserves, the following disclosures are required:

numbers of shares authorised, issued and fully paid, and issued but not fully paid

par value (or that shares do not have a par value)

a reconciliation of the number of shares outstanding at the beginning and the end of the

period

description of rights, preferences, and restrictions

treasury shares, including shares held by subsidiaries and associates

shares reserved for issuance under options and contracts

a description of the nature and purpose of each reserve within equity.

Additional disclosures are required in respect of entities without share capital and where an entity

has reclassified puttable financial instruments.

2.3 Statement of profit or loss and other comprehensive income

Concepts of profit or loss and comprehensive income

Profit or loss is defined as "the total of income less expenses, excluding the components of other

comprehensive income". Other comprehensive income is defined as comprising "items of income

and expense (including reclassification adjustments) that are not recognised in profit or loss as

required or permitted by other IFRSs". Total comprehensive income is defined as "the change in

equity during a period resulting from transactions and other events, other than those changes

resulting from transactions with owners in their capacity as owners".

Comprehensive income

for the period

Profit

or loss

Other

comprehensive income

All items of income and expense recognised in a period must be included in profit or loss unless

a Standard or an Interpretation requires otherwise. Some IFRSs require or permit that some

Page | 7

Chapter 1: Financial accounting review

components to be excluded from profit or loss and instead to be included in other comprehensive

income.

Examples of items recognised outside of profit or loss

Changes

in

revaluation

surplus

where

the

revaluation

method

is

used

under IAS 16 Property, Plant and Equipment and IAS 38 Intangible Assets

Remeasurements of a net defined benefit liability or asset recognised in accordance

with IAS 19 Employee Benefits (2011)

Exchange differences from translating functional currencies into presentation currency

in accordance with IAS 21 The Effects of Changes in Foreign Exchange Rates

Gains and losses on remeasuring available-for-sale financial assets in accordance

with IAS 39 Financial Instruments: Recognition and Measurement

The effective portion of gains and losses on hedging instruments in a cash flow hedge

under IAS 39 or IFRS 9 Financial Instruments

Gains and losses on remeasuring an investment in equity instruments where the entity

has elected to present them in other comprehensive income in accordance with IFRS 9

The effects of changes in the credit risk of a financial liability designated as at fair value

through profit and loss under IFRS 9.

In addition, IAS 8 Accounting Policies, Changes in Accounting Estimates and Errors requires the

correction of errors and the effect of changes in accounting policies to be recognised outside

profit or loss for the current period.

Choice in presentation and basic requirements

An entity has a choice of presenting:

a single statement of profit or loss and other comprehensive income, with profit or loss

and other comprehensive income presented in two sections, or

two statements:

o

a separate statement of profit or loss

a statement of comprehensive income, immediately following the statement of

profit or loss and beginning with profit or loss

The statement(s) must present:

Page | 8

Chapter 1: Financial accounting review

profit or loss

total other comprehensive income

comprehensive income for the period

an allocation of profit or loss and comprehensive income for the period between noncontrolling interests and owners of the parent.

Profit or loss section of statement

The following minimum line items must be presented in the profit or loss section (or separate

statement of profit or loss, if presented):

revenue

gains and losses from the derecognition of financial assets measured at amortised cost

finance costs

share of the profit or loss of associates and joint ventures accounted for using the equity

method

certain gains or losses associated with the reclassification of financial assets

tax expense

a single amount for the total of discontinued items

Expenses recognised in profit or loss should be analysed either by nature (raw materials, staffing

costs, depreciation, etc.) or by function (cost of sales, selling, administrative, etc.). If an entity

categorises by function, then additional information on the nature of expenses at a minimum

depreciation, amortisation and employee benefits expense must be disclosed.

Other comprehensive income section

The other comprehensive income section is required to present line items which are classified by

their nature, and grouped between those items that will or will not be reclassified to profit and

loss in subsequent periods.

An entity's share of OCI of equity-accounted associates and joint ventures is presented in

aggregate as single line items based on whether or not it will subsequently be reclassified to

profit or loss.

When an entity presents subtotals, those subtotals shall be comprised of line items made up of

amounts recognised and measured in accordance with IFRS; be presented and labelled in a clear

and understandable manner; be consistent from period to period; not be displayed with more

Page | 9

Chapter 1: Financial accounting review

prominence than the required subtotals and totals; and reconciled with the subtotals or totals

required in IFRS.

Other requirements

Additional line items may be needed to fairly present the entity's results of operations. Items

cannot be presented as 'extraordinary items' in the financial statements or in the notes.

Certain items must be disclosed separately either in the statement of comprehensive income or

in the notes, if material, including:

write-downs of inventories to net realisable value or of property, plant and equipment to

recoverable amount, as well as reversals of such write-downs

restructurings of the activities of an entity and reversals of any provisions for the costs of

restructuring

disposals of items of property, plant and equipment

disposals of investments

discontinuing operations

litigation settlements

other reversals of provisions

2.4 Statement of cash flows

Rather than setting out separate requirements for presentation of the statement of cash flows,

IAS 1 refers to IAS 7 Statement of Cash Flows.

Statement of changes in equity

IAS 1 requires an entity to present a separate statement of changes in equity. The statement must

show: total comprehensive income for the period, showing separately amounts attributable to

owners of the parent and to non-controlling interests

the effects of any retrospective application of accounting policies or restatements made

in accordance with IAS 8, separately for each component of other comprehensive income

reconciliations between the carrying amounts at the beginning and the end of the period

for each component of equity, separately disclosing:

Page | 10

profit or loss

other comprehensive income

Chapter 1: Financial accounting review

transactions with owners, showing separately contributions by and distributions

to owners and changes in ownership interests in subsidiaries that do not result

in a loss of control

The following amounts may also be presented on the face of the statement of changes in equity,

or they may be presented in the notes:

amount of dividends recognised as distributions

the related amount per share.

Notes to the financial statements

The notes must:

present information about the basis of preparation of the financial statements and the

specific accounting policies used

disclose any information required by IFRSs that is not presented elsewhere in the financial

statements and

provide additional information that is not presented elsewhere in the financial statements

but is relevant to an understanding of any of them

Notes are presented in a systematic manner and cross-referenced from the face of the financial

statements to the relevant note.

IAS 1 suggests that the notes should normally be presented in the following order:

a statement of compliance with IFRSs

a summary of significant accounting policies applied, including:

o

the measurement basis (or bases) used in preparing the financial statements

the other accounting policies used that are relevant to an understanding of the

financial statements

supporting information for items presented on the face of the statement of financial

position (balance sheet), statement(s) of profit or loss and other comprehensive income,

statement of changes in equity and statement of cash flows, in the order in which each

statement and each line item is presented

other disclosures, including:

o

Page | 11

contingent liabilities (see IAS 37) and unrecognised contractual commitments

Chapter 1: Financial accounting review

non-financial disclosures, such as the entity's financial risk management

objectives and policies (see IFRS 7 Financial Instruments: Disclosures)

2.5 Other disclosures

Judgements and key assumptions

An entity must disclose, in the summary of significant accounting policies or other notes, the

judgements, apart from those involving estimations, that management has made in the process

of applying the entity's accounting policies that have the most significant effect on the amounts

recognised in the financial statements.

Examples cited in IAS 1 include management's judgements in determining:

when substantially all the significant risks and rewards of ownership of financial assets

and lease assets are transferred to other entities

whether, in substance, particular sales of goods are financing arrangements and

therefore do not give rise to revenue.

An entity must also disclose, in the notes, information about the key assumptions concerning the

future, and other key sources of estimation uncertainty at the end of the reporting period, that

have a significant risk of causing a material adjustment to the carrying amounts of assets and

liabilities within the next financial year. These disclosures do not involve disclosing budgets or

forecasts.

Dividends

In addition to the distributions information in the statement of changes in equity (see above), the

following must be disclosed in the notes:

the amount of dividends proposed or declared before the financial statements were

authorised for issue but which were not recognised as a distribution to owners during

the period, and the related amount per share

the amount of any cumulative preference dividends not recognised.

Capital disclosures

An entity discloses information about its objectives, policies and processes for managing capital.

To comply with this, the disclosures include:

Page | 12

Chapter 1: Financial accounting review

qualitative information about the entity's objectives, policies and processes for managing

capital, including:

o

description of capital it manages

nature of external capital requirements, if any

how it is meeting its objectives

quantitative data about what the entity regards as capital

changes from one period to another

whether the entity has complied with any external capital requirements and

if it has not complied, the consequences of such non-compliance.

Puttable financial instruments

IAS 1 requires the following additional disclosures if an entity has a puttable instrument that is

classified as an equity instrument:

summary quantitative data about the amount classified as equity

the entity's objectives, policies and processes for managing its obligation to repurchase

or redeem the instruments when required to do so by the instrument holders, including

any changes from the previous period

the expected cash outflow on redemption or repurchase of that class of financial

instruments and

information about how the expected cash outflow on redemption or repurchase was

determined.

Other information

The following other note disclosures are required by IAS 1 if not disclosed elsewhere in

information published with the financial statements:

domicile and legal form of the entity

country of incorporation

address of registered office or principal place of business

description of the entity's operations and principal activities

if it is part of a group, the name of its parent and the ultimate parent of the group

if it is a limited life entity, information regarding the length of the life

Page | 13

Chapter 1: Financial accounting review

2.6 Deferred Taxes

IAS 12 Income Taxes implements a so-called 'comprehensive balance sheet method' of

accounting for income taxes which recognises both the current tax consequences of transactions

and events and the future tax consequences of the future recovery or settlement of the carrying

amount of an entity's assets and liabilities. Differences between the carrying amount and tax base

of assets and liabilities, and carried forward tax losses and credits, are recognised, with limited

exceptions, as deferred tax liabilities or deferred tax assets, with the latter also being subject to a

'probable profits' test.

Deferred tax liabilities is defined as the amounts of income taxes payable in future periods in

respect of taxable temporary differences. Taxable temporary differences are the temporary

differences that will result in taxable amounts in determining taxable profit (tax loss) of future

periods when the carrying amount of the asset or liability is recovered or settled.

Deferred tax assets is the amounts of income taxes recoverable in future periods in respect of:

o

deductible temporary differences

the carry forward of unused tax losses, and

the carry forward of unused tax credits

Deferred tax assets and deferred tax liabilities can be calculated using the following formulae:

Temporary difference

Carrying amount

Tax base

Deferred tax asset or liability

Temporary difference

Tax rate

Where, the tax base of an asset or liability is the amount attributed to that asset or liability for tax

purposes.

The following formula can be used in the calculation of deferred taxes arising from unused tax

losses or unused tax credits:

Deferred tax asset

Unused tax loss or unused tax credits

Tax rate

The general principle in IAS 12 is that a deferred tax liability is recognised for all taxable temporary

differences. There are three exceptions to the requirement to recognise a deferred tax liability, as

follows:

liabilities arising from initial recognition of goodwill

Page | 14

Chapter 1: Financial accounting review

liabilities arising from the initial recognition of an asset/liability other than in a business

combination which, at the time of the transaction, does not affect either the accounting

or the taxable profit

liabilities arising from temporary differences associated with investments in subsidiaries,

branches, and associates, and interests in joint arrangements, but only to the extent that

the entity is able to control the timing of the reversal of the differences and it is probable

that the reversal will not occur in the foreseeable future.

2.6.1 Measurement of deferred tax

Deferred tax assets and liabilities are measured at the tax rates that are expected to apply to the

period when the asset is realised or the liability is settled, based on tax rates/laws that have been

enacted or substantively enacted by the end of the reporting period. The measurement reflects

the entity's expectations, at the end of the reporting period, as to the manner in which the

carrying amount of its assets and liabilities will be recovered or settled.

IAS 12 provides the following guidance on measuring deferred taxes:

Where the tax rate or tax base is impacted by the manner in which the entity recovers its

assets or settles its liabilities (e.g. whether an asset is sold or used), the measurement of

deferred taxes is consistent with the way in which an asset is recovered or liability settled

Where deferred taxes arise from revalued non-depreciable assets (e.g. revalued land),

deferred taxes reflect the tax consequences of selling the asset

Deferred

taxes

arising

from

investment

property

measured

at

fair

value

under IAS 40 Investment Property reflect the rebuttable presumption that the investment

property will be recovered through sale

If dividends are paid to shareholders, and this causes income taxes to be payable at a

higher or lower rate, or the entity pays additional taxes or receives a refund, deferred

taxes are measured using the tax rate applicable to undistributed profits

Deferred tax assets and liabilities cannot be discounted.

The following formula summarises the amount of tax to be recognised in an accounting period:

Tax to recognise for

the period

Page | 15

Current tax for the period

Movement in deferred tax

balances for the period

Chapter 1: Financial accounting review

2.7 Earnings Per Share (EPS)

IAS 33 Earnings Per Share sets out how to calculate both basic earnings per share (EPS) and

diluted EPS. The calculation of Basic EPS is based on the weighted average number of ordinary

shares outstanding during the period, whereas diluted EPS also includes dilutive potential

ordinary shares (such as options and convertible instruments) if they meet certain criteria.

Basic EPS is calculated by dividing profit or loss attributable to ordinary equity holders of the

parent entity (the numerator) by the weighted average number of ordinary shares outstanding

(the denominator) during the period.

=

Net profit or loss attributable to ordinary shareholders

Weighted average number of ordinary shares outstanding during the period

The earnings numerators (profit or loss from continuing operations and net profit or loss) used

for the calculation should be after deducting all expenses including taxes, minority interests (NCI),

and preference dividends.

The denominator (number of shares) is calculated by adjusting the shares in issue at the

beginning of the period by the number of shares bought back or issued during the period,

multiplied by a time-weighting factor.

Diluted EPS is calculated by adjusting the earnings and number of shares for the effects of dilutive

options and other dilutive potential ordinary shares. The effects of anti-dilutive potential ordinary

shares are ignored in calculating diluted EPS.

Diluted EPS = [(net income - preferred dividend) / weighted average number of shares

outstanding - impact of convertible securities - impact of options, warrants and other dilutive

securities]

If EPS is presented, the following disclosures are required:

the amounts used as the numerators in calculating basic and diluted EPS, and a

reconciliation of those amounts to profit or loss attributable to the parent entity for the

period

the weighted average number of ordinary shares used as the denominator in calculating

basic and diluted EPS, and a reconciliation of these denominators to each other

Page | 16

Chapter 1: Financial accounting review

instruments (including contingently issuable shares) that could potentially dilute basic

EPS in the future, but were not included in the calculation of diluted EPS because they

are antidilutive for the period(s) presented

a description of those ordinary share transactions or potential ordinary share transactions

that occur after the balance sheet date and that would have changed significantly the

number of ordinary shares or potential ordinary shares outstanding at the end of the

period if those transactions had occurred before the end of the reporting period.

Examples include issues and redemptions of ordinary shares issued for cash, warrants

and options, conversions, and exercises

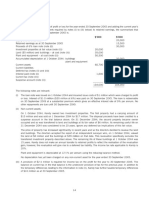

Illustration of EPS and Diluted EPS

Consider the income statement and the balance sheet below:

Page | 17

Chapter 1: Financial accounting review

How did we get $3.82 and $3.61 respectively?

The companys $32.47 million net income is divided by the 8.5 million shares of stock the business

has issued to compute its $3.82 EPS.

Assume that its capital stock is being traded at $70 per share. The Big Board (as it is called)

requires that the market cap (total value of the shares issued and outstanding) be at least $100

million and that it have at least 1.1 million shares available for trading.

With 8.5 million shares trading at $70 per share, the companys market cap is $595 million, well

above the NYSEs minimum. At the end of the year, this corporation has 8.5 million stock shares

outstanding, which refers to the number of shares that have been issued and are owned by its

stockholders. Thus, its EPS is $3.82, as just computed.

The business is committed to issuing additional capital stock shares in the future for stock options

that the company has granted to its executives, and it has borrowed money on the basis of debt

instruments that give the lenders the right to convert the debt into its capital stock.

Under terms of its management stock options and its convertible debt, the business may have to

issue 500,000 additional capital stock shares in the future. Dividing net income by the number of

Page | 18

Chapter 1: Financial accounting review

shares outstanding plus the number of shares that could be issued in the future gives the

following computation of EPS:

$32,470,000 net income 9,000,000 capital stock shares issued and potentially issuable =

$3.61 EPS

2.8 Inventory

Inventories include assets held for sale in the ordinary course of business (finished goods), assets

in the production process for sale in the ordinary course of business (work in process), and

materials and supplies that are consumed in production (raw materials).

However, IAS 2 excludes certain inventories from its scope:

work in process arising under construction contracts (see IAS 11 Construction Contracts)

financial instruments (see IAS 39 Financial Instruments: Recognition and Measurement)

biological assets related to agricultural activity and agricultural produce at the point of

harvest (see IAS 41 Agriculture).

Also, while the following are within the scope of the standard, IAS 2 does not apply to the

measurement of inventories held by:

producers of agricultural and forest products, agricultural produce after harvest, and

minerals and mineral products, to the extent that they are measured at net realisable

value (above or below cost) in accordance with well-established practices in those

industries. When such inventories are measured at net realisable value, changes in that

value are recognised in profit or loss in the period of the change

commodity brokers and dealers who measure their inventories at fair value less costs to

sell. When such inventories are measured at fair value less costs to sell, changes in fair

value less costs to sell are recognised in profit or loss in the period of the change.

IAS 2 Inventories contains the requirements on how to account for most types of inventory. The

standard requires inventories to be measured at the lower of cost and net realisable value (NRV)

and outlines acceptable methods of determining cost, including specific identification (in some

cases), first-in first-out (FIFO) and weighted average cost.

In measuring the value of inventory, the cost should include all:

Page | 19

Chapter 1: Financial accounting review

costs of purchase (including taxes, transport, and handling) net of trade discounts

received

costs of conversion (including fixed and variable manufacturing overheads) and

other costs incurred in bringing the inventories to their present location and condition

IAS 23 Borrowing Costs identifies some limited circumstances where borrowing costs (interest)

can be included in cost of inventories that meet the definition of a qualifying asset.

Inventory cost should NOT include:

abnormal waste

storage costs

administrative overheads unrelated to production

selling costs

foreign exchange differences arising directly on the recent acquisition of inventories

invoiced in a foreign currency

interest cost when inventories are purchased with deferred settlement terms.

The standard cost and retail methods may be used for the measurement of cost, provided that

the results approximate actual cost.

For inventory items that are not interchangeable, specific costs are attributed to the specific

individual items of inventory.

3. Consolidated Financial Statements

Consolidated financial statements is the financial statements of a group in which the assets,

liabilities, equity, income, expenses and cash flows of the parent and its subsidiaries are presented

as those of a single economic entity.

IFRS 10 Consolidated Financial Statements outlines the requirements for the preparation and

presentation of consolidated financial statements, requiring entities to consolidate entities it

controls. Control requires exposure or rights to variable returns and the ability to affect those

returns through power over an investee.

A parent prepares consolidated financial statements using uniform accounting policies for like

transactions and other events in similar circumstances.

Page | 20

Chapter 1: Financial accounting review

However, a parent need not present consolidated financial statements if it meets all of the

following conditions:

it is a wholly-owned subsidiary or is a partially-owned subsidiary of another entity and

its other owners, including those not otherwise entitled to vote, have been informed

about, and do not object to, the parent not presenting consolidated financial statements

its debt or equity instruments are not traded in a public market (a domestic or foreign

stock exchange or an over-the-counter market, including local and regional markets)

it did not file, nor is it in the process of filing, its financial statements with a securities

commission or other regulatory organisation for the purpose of issuing any class of

instruments in a public market, and

its ultimate or any intermediate parent of the parent produces financial statements

available for public use that comply with IFRSs, in which subsidiaries are consolidated or

are measured at fair value through profit or loss in accordance with IFRS 10.

Consolidated financial statements:

combine like items of assets, liabilities, equity, income, expenses and cash flows of the

parent with those of its subsidiaries

offset (eliminate) the carrying amount of the parent's investment in each subsidiary and

the parent's portion of equity of each subsidiary (IFRS 3 Business Combinations explains

how to account for any related goodwill)

eliminate in full intragroup assets and liabilities, equity, income, expenses and cash flows

relating to transactions between entities of the group (profits or losses resulting from

intragroup transactions that are recognised in assets, such as inventory and fixed assets,

are eliminated in full).

A reporting entity includes the income and expenses of a subsidiary in the consolidated financial

statements from the date it gains control until the date when the reporting entity ceases to

control the subsidiary. Income and expenses of the subsidiary are based on the amounts of the

assets and liabilities recognised in the consolidated financial statements at the acquisition date.

The parent and subsidiaries are required to have the same reporting dates, or consolidation based

on additional financial information prepared by subsidiary, unless impracticable. Where

impracticable, the most recent financial statements of the subsidiary are used, adjusted for the

effects of significant transactions or events between the reporting dates of the subsidiary and

Page | 21

Chapter 1: Financial accounting review

consolidated financial statements. The difference between the date of the subsidiary's financial

statements and that of the consolidated financial statements shall be no more than three months.

Page | 22

Chapter 3: Cost Management

Chapter 2: Managing Organisation

Business organisation is an entity formed for the purpose of carrying on commercial enterprise.

Business enterprises customarily take one of three forms: individual proprietorships, partnerships,

or limited-liability companies (or corporations).

In the first form, a single person holds the entire operation as his personal property, usually

managing it on a day-to-day basis. Most businesses are of this type. The second form, the

partnership which may have from 2 to 50 or more members, as in the case of large law and

accounting firms, brokerage houses, and advertising agencies. This form of business is owned by

the partners themselves; they may receive varying shares of the profits depending on their

investment or contribution. Whenever a member leaves or a new member is added, the firm must

be reconstituted as a new partnership.

The third form, the limited-liability company, or corporation, denotes incorporated groups of

personsthat is, a number of persons considered as a legal entity (or fictive person) with

property, powers, and liabilities separate from those of its members. This type of company is also

legally separate from the individuals who work for it, whether they be shareholders or employees

or both; it can enter into legal relations with them, make contracts with them, and sue and be

sued by them. Most large industrial and commercial organisations are limited-liability companies.

1. The Nature of Limited Companies

A company can be defined as an "artificial person", invisible, intangible, created by or under law,

with a discrete legal entity, perpetual succession and a common seal. It is not affected by the

death, insanity or insolvency of an individual member. A limited company is a company in which

the liability of each shareholder is limited to the amount individually invested" with corporations

being "the most common example of a limited company."

The ownership of a limited company is represented by shares. There may be several 'classes' of

shares in a company. Ordinary shares represent the 'real' ownership of a company. Preferred

shares do not convey any right to ownership. They entitle their holders to a dividend each year.

A preferred dividend is usually fixed, and expressed as a percentage amount each year on the

nominal value of the shares. Ordinary shareholders receive dividends out of profits, after

Page | 23

Chapter 3: Cost Management

preferred dividends have been paid. The amount of dividend in any year depends on the

profitability of the company.

A company can contract, sue and be sued in its incorporated name and capacity. Shareholders

liability for the losses of the company is limited to their share contribution only. This is what

makes it a separate legal entity from its shareholders. The business can be sued on its own and

not involve its shareholders. The company does not belong to any person since one person can

own only a part of it.

2. Mission, Objectives and Targets

Mission statements are normally short and simple statements which outline what the

organisation's purpose is and are related to the specific sector an organisation operates in.

Mission statements are concerned about the current times and tend to answer questions about

what the business does or what makes them stand out compared to the competition. There is no

standard format for setting a mission statement, but they should possess certain characteristics:

Brevity - easy to understand and remember

Flexibility - to accommodate change

Distinctiveness - to make the firm stand out.

The objectives, unlike the mission statement, are actionable and measurable steps. There are

usually multiple goals and objectives needed to achieve the businesss mission statement. There

is a primary corporate objective (restricted by certain constraints on corporate activity) and other

secondary objectives which are strategic objectives which should combine to ensure the

achievement of the primary corporate objective.

(a) For example, if a company sets itself an objective of growth in profits, as its primary objective,

it will then have to develop strategies by which this primary objective can be achieved.

(b) Secondary objectives might then be concerned with sales growth, continual technological

innovation, customer service, product quality, efficient resource management (e.g. labour

productivity) or reducing the company's reliance on debt capital.

Objectives may be long-term or short-term as well.

Page | 24

Chapter 3: Cost Management

(a) A company that is suffering from a recession in its core industries and making losses in the

short term might continue to have a primary objective in the long term of achieving a steady

growth in earnings or profits, but in the short term, its primary objective might switch to survival.

(b) Secondary objectives will range from short-term to long-term. Planners will formulate

secondary objectives within the guidelines set by the primary objective, after selecting strategies

for achieving the primary objective.

Target is a measurement of how successfully the aim is reaching its objective. Targets are the

SMART and precise details of the objectives to be realised in a time frame. Targets can also be

used as standards for measuring the performance of the organisation and departments in it.

3. Performance Measurement and Performance Management

Its the 2012 Olympics. How do you think performance is going to be measured at the games by

the teams involved? The number of gold medals? The number of world records? Their position

in the medals table?

Now come back to the present day as teams are preparing for the games. How do you think

performance is being managed? One thing is for sure, it wont involve counting the number of

medals they hope to win. Instead the focus will be on the type of training being given, the diets

being prepared, and the way in which equipment and facilities are being used. To ensure these

can take place, budgets and other resources will be allocated to the most appropriate activities,

while reporting will look at their progress and whether the athlete has achieved set milestones.

In short, performance management is all about preparing and monitoring the athlete, and not on

measuring the outcomes they hope to achieve.

Performance measurement focuses on results and allows users to analyse those results through

charts, grids, trends, and by drilling-down to even greater depths of detail. However, what they

dont reveal is the process that individual managers went through in setting the initial targets;

the actions that were going to be required; the anticipated state of the business environment for

which those actions were conceived; whether or not the required actions were actually carried

out; and whether those actions actually contributed to success.

Without this knowledge,

measures are at best misleading, and in the worst case will promote responses that are ill

considered and damaging to the long-term prospects of the organisation.

Page | 25

Chapter 3: Cost Management

Performance management by contrast is all to do with the business processes and day-to-day

actions that lead to strategic goals. This includes how management choose a particular course

of action in a given business environment, as well as how those actions relate to other

departments and the overall achievement of company strategy. A true performance management

system combines many processes. It starts out by supporting the setting up of an operational

plan that is tied to strategic goals. It allows managers to collaborate with others on developing

initiatives to which resources can be allocated that will eventually form part of a departmental

budget.

Performance management systems allow these initiatives to be assessed in various combinations

so that the best can be selected as part of an agreed plan. The system will then go on to track

the implementation of agreed initiatives and warn users and appropriate managers if activities

have not been completed or if they are not having the desired effect on strategic goals.

Where goals are not being met or are being forecast to miss, a performance management system

will allow mangers to propose changes and try out alternative scenarios to put the plan back on

course. Once these are agreed, the system will adjust any budgets, warn users of those changes

and then track the new version.

4. Responsibility Centre

Responsibility centres are identifiable segments within a company for which individual managers

have accepted authority and accountability. Responsibility centres define exactly what assets and

activities each manager is responsible for. How to classify any given department depends on

which aspects of the business the department has authority over.

Managers prepare a responsibility report to evaluate the performance of each responsibility

centre. This report compares the responsibility centres budgeted performance with its actual

performance, measuring and interpreting individual variances.

Responsibility centres can be classified by the scope of responsibility assigned and decisionmaking authority given to individual managers.

The following are the four common types of respon-sibility centres:

Page | 26

Chapter 3: Cost Management

4.1. Cost Centres

A cost or expense centre is a segment of an organisation in which the managers are held

re-sponsible for the cost incurred in that segment but not for revenues. Responsibility in a cost

centre is restricted to cost. For planning purposes, the budget estimates are cost estimates; for

control purposes, performance evaluation is guided by a cost variance equal to the difference

between the actual and budgeted costs for a given period. Cost centre managers have control

over some or all of the costs in their segment of business, but not over revenues. Cost centres

are widely used forms of responsibil-ity centres.

In manufacturing organisations, the production and service departments are classified as cost

centre. Also, a marketing department, a sales region or a single sales representative can be

defined as a cost centre. Cost centre may vary in size from a small department with a few

employees to an entire manufacturing plant. In addition, cost centres may exist within other cost

centres.

For example, a manager of a manufacturing plant organised as a cost centre may treat individual

depart-ments within the plant as separate cost centres, with the department managers reporting

directly to plant manager. Cost centre managers are responsible for the costs that are controllable

by them and their subordinates. However, which costs should be charged to cost centres, is an

important question in evaluating cost centre managers.

4.2. Revenue centres

A revenue centre is a segment of the organisation which is primarily responsible for generating

sales revenue. A revenue centre manager does not possess control over cost, investment in assets,

but usually has control over some of the expense of the marketing department. The performance

of a revenue centre is evaluated by comparing the actual revenue with budgeted revenue, and

actual marketing expenses with budgeted marketing expenses. The Marketing Manager of a

product line, or an individual sales representative are examples of revenue centres.

4.3. Profit Centre

A profit centre is a segment of an organisation whose manager is responsible for both revenues

and costs. In a profit centre, the manager has the responsibility and the authority to make

decisions that affect both costs and revenues (and thus profits) for the department or division.

Page | 27

Chapter 3: Cost Management

The main purpose of a profit centre is to earn profit. Profit centre managers aim at both the

production and marketing of a product.

The performance of the profit centre is evaluated in terms of whether the centre has achieved its

budgeted profit. A division of the company which produces and markets the products may be

called a profit centre. Such a divisional manager determines the selling price, marketing

programmes and production policies.

Profit centres make managers more concerned with finding ways to increase the centres revenue

by increasing production or improving distribution methods. The manager of a profit centre does

not make decisions concerning the plant assets available to the centre. For example, the manager

of the sporting goods department does not make the decisions to expand the available floor

space for the department.

Mostly profit centres are created in an organisation in which they (profit divisions) sell products

or services outside the company. In some cases, profit centres may be selling products or services

within the company. For example, repairs and maintenance department in a company can be

treated as a profit centre if it is allowed to bill other production departments for the services

provided to them. Similarly, the data processing department may bill each of companys

administrative and operating departments for providing computer-related services.

An example of profit centres in a super market having different retail departments is displayed in

the figure below.

Figure 2 Super Market Profit Centres

In profit centres, managers are encouraged to take important decisions regarding the activities

and operations of their divisions. Profit centres are generally created in terms of product or

process which has grown in size and has profit responsibility. In some organizations, profit centres

are given complete autonomy on sourcing supplies and making sales.

However, in other organisations, such independence may not be found. Top management does

not allow profit centre divisions to buy from outside sources if there is idle capacity within the

Page | 28

Chapter 3: Cost Management

firm. Also, the top management may be hesitant to part with designs and other specifications to

maintain quality and safety of the product and due to fear of losing the market that the firm has

already created for its products.

4.4. Investment Centre

An investment centre is responsible for both profits and investments. The investment centre

manager has control over revenues, expenses and the amounts invested in the centres assets.

He also formulates the credit policy which has a direct influence on debt collection, and the

inventory policy which determines the investment in inventory.

The manager of an investment centre has more authority and responsibility than the manager of

either a cost centre or a profit centre. Besides controlling costs and revenues, he has investment

responsibility too. Investment on asset responsibility means the authority to buy, sell and use

divisional assets.

5. Cost Accounting and Management Accounting

Cost accounting is a task of collecting, analysing, summarising and evaluating various alternative

courses of action. Its goal is to advise the management on the most appropriate course of action

based on the cost efficiency and capability. Cost accounting provides the detailed cost

information that management needs to control current operations and plan for the future.

Since managers are making decisions only for their own organisation, there is no need for the

information to be comparable to similar information from other organisations. Instead,

information must be relevant for a particular environment. Cost accounting information is

commonly used in financial accounting information, but its primary function is for use by

managers to facilitate making decisions. A costing system is designed to monitor the costs

incurred by the business. The system is comprised of a set of forms, processes, controls, and

reports that are designed to aggregate and report to management about revenues, costs, and

profitability. Unlike the accounting systems that help in the preparation of financial reports

periodically, the cost accounting systems and reports are not subject to rules and standards i.e.

IFRS. As a result, there is a wide variety in the cost accounting systems of the different companies

and sometimes even in different parts of the same company or organisation.

Page | 29

Chapter 3: Cost Management

Management accounting involves preparing and providing timely financial and statistical

information to business managers so that they can make day-to-day and short-term managerial

decisions.

Management accounting (also known as managerial or cost accounting) is different from financial

accounting, in that it produces reports for a companys internal stakeholders, as opposed to

external stakeholders. The result of management accounting is periodic reports for e.g. the

companys department managers, chief executive officer, etc.

The following table summarises the main differences between management accounting and

financial accounting:

Management accounting

Financial accounting

A management accounting system produces

A financial accounting system produces

information

information that is used by parties external to

that

is

used

within

an

organisation, by managers and employees.

the organisation, such as shareholders, banks

and creditors.

Management accounting helps management

Financial accounting provides a record of the

to record, plan and control activities and aids

performance of an organisation over a

the decision-making process.

defined period and the state of affairs at the

end of that period.

There is no legal requirement for an

Limited companies are required by the law of

organisation to use management accounting.

most countries to prepare financial accounts.

Management

Financial accounting concentrates on the

accounting

can

focus

on

specific areas of an organisation's activities.

organisation

Information may aid a decision rather than be

revenues and costs from different operations.

an end-product of a decision.

Financial accounts are an end in themselves.

Management accounting information may be

Most financial accounting information is of a

monetary or alternatively non-monetary.

monetary nature.

Management accounting provides both an

Financial accounting presents an essentially

historical record and a future planning tool.

historical picture of past operations.

Page | 30

as

whole,

aggregating

Chapter 3: Cost Management

No strict rules govern the way in which

Financial accounting must operate within a

management

framework determined

accounting

operates.

The

by law and by

management accounts and information are

accounting standards (e.g., IASs and IFRSs). In

prepared in a format that is of use to

principle the financial accounts of different

managers.

organisations can be easily compared.

6. Organisational Structures

An organisational structure defines how activities such as task allocation, coordination and

supervision are directed toward the achievement of organisational aims.

The way that a companys structure develops often falls into a tall (vertical) structure or a flat

(horizontal) structures. Tall structures are more of what we think of when we visualise an

organisational chart with the CEO at the top and multiple levels of management. Flat

organisational structures differ in that there are fewer levels of management and employees often

have more autonomy.

Tall Organisational Structure

Large, complex organisations often require a taller hierarchy. In its simplest form, a tall structure

results in one long chain of command similar to the military. As an organisation grows, the

number of management levels increases and the structure grows taller. In a tall structure,

managers form many ranks and each has a small area of control. Although tall structures have

more management levels than flat structures, there is no definitive number that draws a line

between the two.

The pros of tall structures lie in clarity and managerial control. The narrow span of control allows

for close supervision of employees. Tall structures provide a clear, distinct layers with obvious

lines of responsibility and control and a clear promotion structure. Challenges begin when a

structure gets too tall. Communication begins to take too long to travel through all the levels.

These communication problems hamper decisionmaking and hinder progress.

Page | 31

Chapter 3: Cost Management

Figure 3: Tall Organisational Structure

Figure 4: Flat Organisational

Structure

Flat Organisational Structure

Flat structures have fewer management levels,

with each level controlling a broad area or group. Flat organizations focus on empowering

employees rather than adhering to the chain of command. By encouraging autonomy and selfdirection, flat structures attempt to tap into employees creative talents and to solve problems by

collaboration.

Flat organisations offer more opportunities for employees to excel while promoting the larger

business vision. That is, there are more people at the top of each level. For flat structures to

work, leaders must share research and information instead of hoarding it. If they can manage to

be open, tolerant and even vulnerable, leaders excel in this environment. Flatter structures are

flexible and better able to adapt to changes. Faster communication makes for quicker decisions,

but managers may end up with a heavier workload. Instead of the military style of tall structures,

flat organizations lean toward a more democratic style.

The heavy managerial workload and large number of employees reporting to each boss

sometimes results in confusion over roles. Bosses must be team leaders who generate ideas and

help others make decisions. When too many people report to a single manager, his job becomes

impossible. Employees often worry that others manipulate the system behind their backs by

reporting to the boss; in a flat organisation, that means more employees distrusting higher levels

of authority.

7. Divisionalisation, Departmentation and Decentralisation

Divisionalisation is the division of a business into autonomous divisions, regions or product

businesses, each with its own revenues, expenditures and capital asset purchase programmes,

and therefore each with its own profit and loss responsibility.

Each division of the organisation might be:

A subsidiary company under the holding company

Page | 32

Chapter 3: Cost Management

A profit centre or investment centre within a single company

Successful divisionalisation requires certain key conditions.

(a) Each division must have properly delegated authority, and must be held properly accountable

to head office (e.g. for profits earned).

(b) Each unit must be large enough to support the quantity and quality of management it needs.

(c) The unit must not rely on head office for excessive management support.

(d) Each unit must have a potential for growth in its own area of operations.

(e) There should be scope and challenge in the job for the management of each unit.

(f) If units deal with each other, it should be as an 'arm's length' transaction. There should be no

insistence on preferential treatment to be given to a 'fellow unit' by another unit of the overall

organisation.

The benefits and drawbacks of divisionalisation may be summarised as follows.

Advantages

Disadvantages

Focuses the attention of management below

In some businesses, it is impossible to identify

'top level' on business performance.

completely independent products or markets

for which separate divisions can be set up.

Reduces

the

likelihood

of

unprofitable

products and activities being continued.

Divisionalisation is only possible at a fairly

senior management level, because there is a

limit to how much discretion can be used in

the division of work. For example, every

product needs a manufacturing function and

a selling function.

Encourages a greater attention to efficiency,

There may be more resource problems. Many

lower costs and higher profits.

divisions get their resources from head office

in competition with other divisions.

Gives more authority to junior managers, and

Reduces the number of levels of management.

so grooms them for more senior positions in

The top executives in each division should be

the future (planned managerial succession).

able to report directly to the chief executive of

the holding company.

Page | 33

Chapter 3: Cost Management

Departmentation is a process of grouping and sub-grouping. This is the first task and does not

directly relate to decentralisation. Organisations can be departmentalised on a functional basis

(with separate departments for production, marketing, finance etc.), a geographical basis (by

region, or country), a product basis (e.g. worldwide divisions for product X, Y etc.), a brand basis,

or a matrix basis (e.g. someone selling product X in country A would report to both a product X

manager and a country A manager). Organisation structures often feature a variety of these types,

as hybrid structures.

Decentralisation, however, is a diffusion of authority within the entire enterprise and also within

a department. It relates to positions characterised by organisation for better management.

Page | 34

Chapter 3: Cost Management

Chapter 3: Cost Management

Cost management is the process of planning and controlling the budget of a business. Cost

management is a form of management accounting that allows a business to predict impending

expenditures to help reduce the chance of going over budget.

1. Costing

A cost management systems (CMS) is part of an overall management information and control

system. A cost management system consists of a set of formal methods developed for planning

and controlling an organisations cost-generating activities relative to its short-term objectives