Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

Seksual Desire Disorder

Enviado por

Larassati UthamiDireitos autorais

Formatos disponíveis

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Seksual Desire Disorder

Enviado por

Larassati UthamiDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

50-55_Montgomery.

qxp

6/16/08

3:15 PM

Page 50

[REVIEW]

Sexual Desire Disorders

by KEITH A. MONTGOMERY, MD

AUTHOR AFFILIATIONS: Dr. Montgomery is a fourth year resident at Wright State University School of Medicine, Department of Psychiatry,

Dayton, Ohio.

ABSTRACT

Hypoactive sexual desire disorder

(HSDD) and sexual aversion disorder

(SAD) are an under-diagnosed group

of disorders that affect men and

women. Despite their prevalence,

these two disorders are often not

addressed by healthcare providers

and patients due their private and

awkward nature. As physicians, we

need to move beyond our own

unease in order to adequately

address our patients sexual

problems and implement appropriate

treatment. Using the Sexual

Response Cycle as the model of the

physiological changes of humans

during sexual stimulation and the

Diagnostic and Statistical Manual

of Mental Disorders, Fourth

Edition this article will review the

current literature on the desire

disorders focusing on prevalence,

etiology, and treatment.

ADDRESS CORRESPONDENCE TO: Dr. Keith Montgomery, Wright State University School of Medicine, Department of Psychiatry, 627 S. Edwin

C. Moses Blvd., Dayton, Ohio 45408-1461; E-mail: montgoka@hotmail.com

KEY WORDS: sexual desire disorders, sexuality, sexual dysfunction, sexual disorders, sexual response cycle, desire disorder, sexual arousal

disorder, hypoactive sexual disorder

INTRODUCTION

Hypoactive sexual desire disorder

(HSDD) and sexual aversion disorder

(SAD) affect both men and women.

Despite their prevalence, these

disorders are often not addressed by

healthcare providers or patients due

to their private and awkward nature.

Using the Sexual Response Cycle as

the model of the physiological

changes of humans during sexual

stimulation and the Diagnostic and

Statistical Manual of Mental

50

Psychiatry 2008 [ J U N E ]

Disorders, Fourth Edition (DSMIV-TR), this article will review the

current literature on the two desire

disorders, focusing on prevalence,

etiology, and treatment. With this

knowledge, hopefully, physicians will

move beyond their unease with the

topic in order to adequately address

patients sexual problems and to

implement appropriate treatment.

Sexuality defined. Sexuality is a

complex interplay of multiple facets,

including anatomical, physiological,

psychological, developmental,

cultural, and relational factors.1 All of

these contribute to an individuals

sexuality in varying degrees at any

point in time as well as developing

and changing throughout the life

cycle. Sexuality in adults consists of

seven components:

Gender identity

Orientation

Intention

50-55_Montgomery.qxp

6/16/08

3:15 PM

Page 51

Desire

Arousal

Orgasm

Emotional satisfaction

Gender identity, orientation, and

intention form sexual identity,

whereas desire, arousal, and orgasm

are components of sexual function.

The interplay of the first six

components contributes to the

emotional satisfaction of the

experience. In addition to the

multiple factors involved in sexuality,

there is the added complexity of the

corresponding sexuality of the

partner. The expression of a persons

sexuality is intimately related to his

or her partners sexuality.2,3

Sexual response cycle. The

sexual response cycle consists of

four phases: desire, arousal, orgasm,

and resolution. Phase 1 of the sexual

response cycle, desire, consists of

three components: sexual drive,

sexual motivation, and sexual wish.

These reflect the biological,

psychological, and social aspects of

desire, respectively. Sexual drive is

produced through

psychoneuroendocrine mechanisms.

The limbic system and the preoptic

area of the anterior-medial

hypothalamus are believed to play a

role in sexual drive. Drive is also

highly influenced by hormones,

medications (e.g., decreased by

antihypertensive drugs, increased by

dopaminergic compounds to treat

Parkinsons disease), and legal and

illegal substances (e.g., alcohol,

cocaine).4

Phase 2, arousal, is brought on by

psychological and/or physiological

stimulation. Multiple physiologic

changes occur in men and women

that prepare them for orgasm,

mainly perpetuated by

vasocongestion. In men, increased

blood flow causes erection, penile

color changes, and testicular

elevation. Vasocongestion in women

leads to vaginal lubrication, clitoral

tumescence, and labial color

changes. In general, heart rate, blood

pressure, and respiratory rate as well

as myotonia of many muscle groups

increase during this phase.5

Phase 3, orgasm, has continued

51

elevation of respiratory rate, heart

rate, and blood pressure and the

voluntary and involuntary

contraction of many muscle groups.

In men, ejaculation is perpetuated by

the contraction of the urethra, vas,

seminal vesicles, and prostate. In

women, the uterus and lower third of

the vagina contract involuntarily.

The duration of the final phase,

resolution, is highly dependent on

whether orgasm was achieved. If

orgasm is not achieved, irritability

and discomfort can result, potentially

lasting for several hours. If orgasm is

achieved, resolution may last 10 to

15 minutes with a sense of calm and

relaxation. Respiratory rate, heart

rate, and blood pressure return to

baseline and vasocongestion

diminishes. Women can have

factors.7 In order for a patient to be

diagnosed with a sexual dysfunction

disorder, a psychophysiologic

problem must exist, the problem

must cause marked distress or

interpersonal difficulty, and the

problem cannot be better accounted

for by another Axis I diagnoses. Also,

two sexual disorders must be ruled

out before one can diagnosis HSDD

or SAD. These are substanceinduced sexual dysfunction and a

sexual disorder due to general

medical condition.

PREVALENCE

The prevalence of desire disorders

is often underappreciated. The

National Health and Social Life

Survey found that 32 percent of

women and 15 percent of men

Despite their prevalence, these disorders are often not

addressed by healthcare providers or patients due to their

private and awkward nature. Physicians must move beyond

their unease in order to adequately address patients sexual

problems and implement appropriate treatment.

multiple successive orgasms

secondary to a lack of a refractory

period.1 The vast majority of men

have a refractory period following

orgasm in which subsequent orgasm

is not possible.6

CRITERIA

As previously stated, there are

two sexual desire disorders. HSDD in

the DSM-IV-TR7 is defined as

persistently or recurrently deficient

(or absent) sexual fantasies and

desire for sexual activity. The

judgment of deficiency or absence is

made by the clinician, taking into

account factors that affect sexual

functioning, such as age and the

context of the persons life. SAD is

defined as persistent or recurrent

extreme aversion to, and avoidance

of, all (or almost all) genital sexual

contact with a sexual partner. The

DSM-IV-TR lists six subtypes:

lifelong, acquired, generalized,

situational, due to psychological

factors, and due to combined

lacked sexual interest for several

months within the last year. The

study population was

noninstitutionalized US English

speaking men and women between

the ages of 18 and 59 years.8 There

are no large study prevalence figures

on SAD, but it is thought to be a rare

disorder. Both HSDD and SAD have

a higher female to male prevalence

ratio, although this discrepancy is

greater in SAD. The desire disorders

can be considered on a continuum of

severity with HSDD being the less

severe of the two disorders.1

ETIOLOGY

The proposed etiology of HSDD

influences how it is subtyped (i.e.,

generalized or situational, lifelong or

acquired). For example, lifelong

HSDD can be due to sexual identity

issues (gender identity, orientation,

or paraphilia) or stagnation in sexual

growth (overly conservative

background, developmental

abnormalities, or abuse). Conversely,

[JUNE]

Psychiatry 2008

51

50-55_Montgomery.qxp

6/11/08

2:40 PM

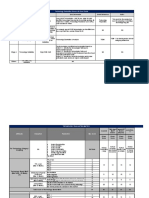

TABLE 1. Common psychotropic classes causing sexual

dysfunction

TRICYCLIC ANTIDEPRESSANTS

Mechanism of action (general)

Inhibits the re-uptake of norepinephrine and serotonin (5-HT)

Modulates norephinephrine and 5-HT activity at

the neural synapse

Mechanism of action (sexual)

Positive

Increased adrenergic 1 activity

Decreased cortisol

Negative

Decreased adrenergic activity

Decreased cholinergic activity

Decreased histamine

Decreased oxytocin

Increased prolactin

Increased serotonin

Direct sexual side effects*

Desire disorders

Dyspareunia

Erection difficulties

Orgasm disorders

Orgasmic inhibition

Anorgasmia

Spontaneous orgasm

Ejaculation disorders

Retarded ejaculation

Ejaculation without orgasm

Anesthetic ejaculation

* Despiramine appears to have the least amount of

sexual side effects of the TCAs

MONOAMINE OXIDASE INHIBITORS

Mechanism of action (general)

Decreases the neural monoamine oxidase enzymatic metabolic breakdown of norepinephrine and

serotonin I

Increases norepinephrine and serotonin activity at

the neural synapse

Mechanism of action (sexual)

Positive

Increased adrenergic 1 activity

Decreased monoamine oxidase

Negative

Decreased -adrenergic activity

Decreased cholinergic activity

Increased prolactin

Increased serotonin

Decreased testosterone

Direct sexual side effects*

Desire disorders

Erection difficulties

Orgasm disorders

Orgasmic inhibition

Decreased number

Ejaculation disorders

Retarded, inhibited

premature ejaculation

diminished

Adapted from Crenshaw TL, Goldberg JP. Sexual

Pharmacology: Drugs That Affect Sexual Functioning.

New York, NY: W. W. Norton & Company, 1996.

52

Psychiatry 2008 [ J U N E ]

Page 52

difficulty in a new sexual

relationship may lead to an acquired

or situational subtype of HSDD.

Although it is theoretically possible

to have no etiology, all appropriate

avenues should be explored,

including whether the patient was

truthful in responses to questions

regarding sexuality and if the patient

is consciously aware that he or she

has a sexual disorder.2,3

Diagnosis and treatment of desire

disorders is often difficult due to

confounding factors, such as high

rates of comorbid disorders and

combined subtype sexual disorders

involving medical and substanceinduced contributors.13 For example,

in a patient being treated for

recurrent major depressive disorder

and obstructive sleep apnea (OSA),

it would be difficult to separate out

whether the cause of his or her

decreased sexual desire was due to

the depressive episode,

antidepressant treatment, OSA,15

multiple potential interpersonal

problems, or a combination of

factors.

Even with a detailed and accurate

longitudinal history, honing in on the

main factor can be difficult.

Decreased sexual desire has been

seen in multiple psychiatric

disorders. For example, individuals

with schizophrenia and major

depression experienced decreased

sexual desire. Before treatment

commences for HSDD and SAD, a

thorough work-up must be done to

first rule out a general medical

condition or a substance that caused

decreased desire or aversion. This

would include a thorough physical

exam and laboratory work-up. An

important physiological maker for

which to test is a thyroid profile,

which would be abnormal in

hypothyroidism and could cause

decreased sexual desire.16 Also, low

testosterone has been shown affect

to desire. Normal physiological

testosterone concentrations range

from 3 to 12ng/mL. The apparent

critical level for sexual function in

males is 3ng/mL.14

A variety of medical conditions

can also decrease sexual desire (e.g.,

diabetes mellitus, hypothyroidism,

Addisons disease, Cushings disease,

temporal lobe lesions, menopause,16

coronary artery disease, heart

failure, renal failure, stroke, and

HIV). Also, as we naturally age,

desire can lessen.14 Many psychiatric

medications can lead to decreased

desire for sex including multiple

classes of antidepressants (selective

serotonin reuptake inhibitors,

norepinephrine serotonin reuptake

inhibitors, tricyclic antidepressants,

monoamine oxidase inhibitors, and

antipsychotics (Table 1).22

Two important biological

mediators of sexual desire are

dopamine and prolactin. Dopamine

acting through the mesolimbic

dopaminergic reward pathway is

hypothesized to increase desire,

whereas prolactin is thought to

decrease libido, although the

mechanisms are poorly understood.

Dopamine directly inhibits prolactin

release from the pituitary gland.

Medications that increase prolactin

release or inhibit dopamine release

can decrease sexual desire along

with other sexual side effects.19

If a patient has no history of

sexual desire problems and has

started a new sexual relationship,

other possibilities for low sexual

desire must be excluded. It is

possible that neither individual has a

desire disorder but rather there is a

marked difference between each

individuals level of desire, creating a

discrepancy. Separate interviews

with each partner are important to

obtain a more accurate picture of the

relationship.13

Important to remember that

HSDD in men is often misdiagnosed

as erectile dysfunction because of

the common misconception that all

men desire sex. This myth has

caused men to not seek treatment

and has also led to misdiagnosis by

health professionals. This may partly

explain the failure rate of adequately

treating erectile dysfunction. As part

of an initial history and physical

examination, a sexual history is

necessary because most patients will

not divulge any sexual problems

unless explicitly asked. There are

50-55_Montgomery.qxp

6/11/08

2:40 PM

Page 53

tests that deal entirely with sexual

desire (Sexual Desire Inventory) and

others have subscales for sexual

desire (International Index of

Erectile Function).14

TREATMENT

Psychotherapy. Although there

are many proposed treatments for

desire disorders, there are virtually

no controlled studies evaluating

them.20 Psychotherapy is a common

treatment for desire disorders. From

a psychodynamic perspective, sexual

dysfunction is caused by unresolved

unconscious conflicts of early

development. Treatment focuses on

bringing awareness to these

unresolved conflicts and how they

impact the patients life. While

improvement may occur, the sexual

dysfunction often becomes

autonomous and persists, requiring

additional techniques to be

employed.

An approach that has shown some

success in the treatment of desire

disorders as well as other sexual

dysfunctions, pioneered by Masters

and Johnson, is dual sex therapy.5 In

this therapy, the couple along with

one male and one female therapist

(gay and lesbian couples may opt for

same-sex therapists) meet together.

The relationship is treated as a

whole, with sexual dysfunction being

one aspect of the relationship.

Another important underlying

premise of this form of therapy is

that only one partner in the

relationship is suffering from sexual

dysfunction and absence of other

major psychopathology. The aim is to

reestablish open communication in

the relationship. Homework

assignments are given to the couple,

the results of which are discussed at

the following session. The couple is

not allowed to engage in any sexual

behavior together other than what is

assigned by the therapists.

Assignments start with foreplay,

which encourages the couple to pay

closer attention to the entire process

of the sexual response cycle as well

as the emotions involved and not

solely on achieving orgasm.

Eventually the couple progresses to

intercourse with encouragement to

try various positions without

completing the act.1

Cognitive behavioral therapy has

been shown to be efficacious in the

treatment of anxiety, depression, and

other psychiatric disorders. Its core

premise is that activating events lead

to negative automatic thoughts.

These negative thoughts in turn

result in disturbed negative feelings

and dysfunctional behaviors. The

goal is to reframe these irrational

beliefs through structured sessions.21

CBT has been also used to treat

sexual desire disorders by focusing

on dysfunctional thoughts,

unrealistic expectations, partner

behavior that decreases desire in

intercourse, and insufficient physical

stimulation. These sessions often

include both partners.20 Specific

exercises may be used. For example,

men with sexual desire disorder or

male erectile disorder may be

instructed to masturbate to address

performance anxiety related to

achieving a full erection and

ejaculation.

Finally, analytically oriented sex

therapy combines sex therapy with

psychodynamic and psychoanalytic

therapy and has shown good results.1

Specifically, for desire disorders due

to developmental and identity issues,

long-term psychodynamic

psychotherapy could be helpful.9 In

general, lifelong and generalized

desire disorders are more difficult to

treat.13

SAD is often progressive and

rarely reverses spontaneously. It is

also treatment-resistant.2 Poor

prognostic indicators are global,

lifelong, comorbid depression, or

associated with anorgasmia.24 Despite

difficulty in treatment, behavioral

therapy has been shown to be

effective for managing SAD.25,26

Pharmacotherapy. Multiple

hormones have been studied for

treatment of sexual desire disorders.

For example, androgen replacement

has been studied as a possible

treatment for HSDD. In patients

with induced or spontaneous

hypogonadism, either pathological

withdrawal and re-introduction or

TABLE 1. Common psychotropic classes causing sexual

dysfunction, continued

SELECTIVE SEROTONIN REUPTAKE INHIBITORS

Mechanism of action (general)

Work through selective serotonin-uptake

inhibition

Mechanism of action (sexual)

Negative

Increased cortisol

Increased opioids

Increased prolactin

Increased serotonin (5-HT)

Direct sexual side effects

Desire disorders

Hyposexuality

Hypersexuality

Orgasm disorders

Orgasmic inhibition

Anorgasmia

Spontaneous orgasm

Ejaculation disorders

Retarded ejaculation

Ejaculatory inhibition

Erection disorders

Inability/difficulty obtaining erection

Decreased quality of erection

Decreased or absent nocturnal/morning erections

ANTIPSYCHOTICS

Mechanism of action (general)

Block dopamine activity

Block sigma receptors and/or 5-HT2 serotonin

receptors

Mechanism of action (sexual)

Negative

Decreased adrenergic 1 activity

Decreased cholinergic activity

Decreased dopamine

Increased prolactin

Decreased testosterone

Decreased LHRH pulsatile activity

Direct sexual side effects

Desire disorders

Hyposexuality

Hypersexuality (rare)

Orgasm disorders

Orgasmic inhibition

Anorgasmia

Diminished number of orgasms

Ejaculation disorders

Retarded ejaculation

Ejaculatory inhibition

Decreased ejaculatory volume

Anesthetic ejaculation

Orgasm without ejaculation

Dyspareunia

Erection disorders

Inability/difficulty obtaining erection

Decreased quality of erection

Priapism

Adapted from Crenshaw TL, Goldberg JP. Sexual

Pharmacology: Drugs That Affect Sexual Functioning.

New York, NY: W. W. Norton & Company, 1996.

[JUNE]

Psychiatry 2008

53

50-55_Montgomery.qxp

6/11/08

2:40 PM

Page 54

exogenous androgens affects the

frequency of sexual fantasies,

arousal, desire, spontaneous

erections during sleep and in the

morning, ejaculation, sexual

activities with and without a partner,

and orgasms through coitus and

masturbation.14 Unfortunately, the

evidence for the efficacy of

testosterone in eugonadal men is

conflicting. Some studies show no

benefit,27 whereas others studies do

show some benefit. For example, a

study by OCarroll and Bancroft

showed that testosterone injections

did have efficacy for sexual interest,

but unfortunately this did not

translate into an improvement in

their sexual relationships.34 One

theory for the lack of efficacy in

eugonadal men is that it is more

difficult to manipulate endogenous

androgen levels with administration

of exogenous androgens due to

efficient homeostatic hormone

mechanisms.14 Androgen

supplementation is available in many

forms, including oral, sublingual,

cream, and dermal patch. Side

effects of testosterone

supplementation in women include

weight gain, clitoral enlargement,

facial hair, hypercholesterolemia,32

changes in long-term breast cancer

risk, and cardiovascular factors.16

Side effects in men of androgen

supplementation include

hypertension and prostatic

enlargement.1 The benefit of

androgen therapy in women is also

not clear.28 Although studies using

supraphysiologic levels of androgens

have shown increased sex libido,

there is the risk of masculinization

from chronic use.18 Testosterone

therapy has shown to improve sexual

function in postmenopausal women

in multiple ways, including increased

desire, fantasy, sexual acts, orgasm,

pleasure, and satisfaction of sexual

acts.16 Roughly half of all

testosterone production in women is

from the ovaries. Thus, an

oophorectomy can cause a sudden

drop of testosterone levels.18 Shifren,

et al.,17 studied 31- to 56-year-old

women who had hysterectomies and

oophorectomies. They were given

54

Psychiatry 2008 [ J U N E ]

150 or 300g of testosterone daily

for 12 weeks. Both groups, with a

dose response relationship, showed

increased frequency of sexual

activities and pleasurable orgasms.

At the 300g dose, there was even

higher scores for frequency of

fantasy, masturbation, and engaging

in sexual intercourse at least once a

week.18 Feelings of general wellbeing

were also increased.17

Estrogen replacement in

postmenopausal women can improve

clitoral and vaginal sensitivity,

increase libido, and decrease vaginal

dryness and pain during intercourse.

Estrogen is available in several

forms, including oral tablets, dermal

patch, vaginal ring, and cream.

Testosterone supplementation has

demonstrated increased libido,

increased vaginal and clitoral

sensitivity, increased vaginal

lubrication, and heightened sexual

arousal.32

Dehydroepiandrosterone-sulfate

(DHEA-S), a testosterone precursor,

has also been studied for the

treatment of sexual desire disorders.

Low physiologic levels of DHEA-S

have been found in women

presenting with HSDD.30 Increased

libido was observed in women with

adrenal insufficiency who were given

DHEA-S.31 Women with breast cancer

reported increased libido while

receiving tamoxifen, which increases

gonadotropin-releasing hormone

levels and therefore testosterone

concentrations.1

Some medications can be used to

increase desire due to their receptor

profiles. For example, amphetamine

and methylphenidate can increase

sexual desire by increasing dopamine

release. Bupropion, a norepinephrine

and dopamine reuptake inhibitor, has

been shown to increase libido.19 A

study by Segraves, et al.,33 showed

that bupropion treatment in

premenopausal women increased

desire, but not to a statistically

significant level compared to

placebo. But, bupropion SR group

did show statistically significant

difference in other measures of

sexual function: increased pleasure

and arousal, and frequency of

orgasms. Multiple herbal remedies,

such as yohimbine and ginseng root,

are purported to increase desire, but

this has not been confirmed in

studies.1

CONCLUSION

Sexual desire disorders are underrecognized, under-treated disorders

leading to a great deal of morbidity

in relationships. A thorough history

and physical examination are critical

to properly diagnosis and determine

the causative agent(s). With

appropriate treatment, improvement

can be made but continued research

in sexual dysfunction is critical in the

sensitive yet ubiquitous area. By

becoming more familiar with

prevalence, etiology, and treatment

of sexual desire disorders, physicians

hopefully will become more

comfortable with the topic so that

they can adequately address

patients sexual problems and to

implement appropriate treatment.

REFERENCES

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

6.

7.

Sadock BJ, Sadock VA. Kaplan

and Sadocks Synopsis of

Psychiatry: Behavioral Sciences

and Clinical Psychiatry, Ninth

Edition. Philadelphia: Lippincott

Williams & Wilkins, 2003.

Levine SB, Risen CB, Althof SE

(eds). Handbook of Clinical

Sexuality for Mental Health

Professionals. New York: BrunnerRoutledge, 2003.

Levine SB. Sexual disorders. In:

Tasman A, Kay J, Lieberman J

(eds). Psychiatry, Second

Edition. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley, 2003.

Levine SB. Reexploring the

concept of sexual desire. J Sex

Marital Ther 2002;28:3951.

Masters WH, Johnson VE. Human

Sexual Response. Boston: Little,

Brown & Co., 1966.

Bechtel S. The practical

encyclopedia of sex and health:

From aphrodisiacs and hormones

to potency, stress, vasectomy, and

yeast infection. Emmaus (PA):

Rodale, 1993.

American Psychiatric Association.

Diagnostic and Statistical

Manual of Mental Disorders,

50-55_Montgomery.qxp

8.

9.

10.

11.

12.

13.

14.

15.

6/11/08

2:40 PM

Page 55

Fourth Edition, Text Revision.

Washington, DC: American

Psychiatric Press Inc., 2000.

Laumann EO, Paik A, Rosen RC.

Sexual dysfunction in the United

States: prevalence and predictors.

JAMA 1999;281:537544.

Kaplan HS. Sexual aversion, sexual

phobias, and panic disorder. New

York: Brunner: Mazel, 1987.

Coleman CC, King BR, BoldenWatson C et al. A placebocontrolled comparison of the

effects on sexual functioning of

bupropion sustained release and

fluoxetine. Clin Ther

2001;23:1040101058.

Hindermarch I. The behavioral

toxicity of antidepressants: effects

on cognition and sexual function.

Int Clin Psychopharmacol

1998;13 (Suppl. 6):S58.

Balercia G, Boscaro M, Lombardo

F, et al. Sexual symptoms in

endocrine diseases: psychosomatic

perspectives. Psychother

Psychosom 2007;76:134140.

Wincze JP, Carey MP. Sexual

Dysfunction: A Guide for

Assessment and Treatment,

Second Edition. New York:

Guilford Press, 2001.

Meuleman E, Van Lankveld J.

Hypoactive sexual desire disorder:

an underestimated condition in

men. Presented at University

Medical Centre St Radboud and

Pompekliniek, Nijmegen, the

Netherlands. 12 July 2004.

Douglas N. Sleep apnea. In: Fauci

AS, Braunwald E, Kasper DL

(eds). Harrisons Principles of

Internal Medicine, Seventeenth

Edition. New York: McGraw Hill,

16.

17.

18.

19.

20.

21.

22.

24.

25.

26.

2008.

Abdallah RT, Simon JA.

Testosterone therapy in women: its

role in the management of

hypoactive sexual desire disorder.

Int J Impotence Res

2007;19:458463.

Shifren JL, Braunstein GD, Simon

JA, et al. Transdermal testosterone

treatment in women with impaired

sexual function after

oophorectomy. N Engl J Med

2000;343:682688.

Basson R. Womens sexual

dysfunction: revised and expanded

sexual definitions. CMAJ

2005;172(10):13271333.

Stahl SM. Essential

Psychopharmacology:

Neuroscientific Basis and

Practical Applications, Second

Edition. New York: Cambridge

University Press, 2000.

Trudel G, Marchand A, Ravart M,

et al. The effect of a cognitivebehavioral group treatment

program on hypoactive sexual

desire in women. Sex Relat Ther

2001;16:145164.

Ellis A, Harper R. A New Guide to

Rational Living. Chatsworth, CA:

Wilshire Book Company, 1975

Crenshaw TL, Goldberg JP. Sexual

Pharmacology: Drugs That Affect

Sexual Functioning. New York,

W. W. Norton & Company, 1996.

Crenshaw TL. The sexual aversion

syndrome. J Sex Marital Ther

1985;11:285292.

Ponticas Y. Sexual aversion versus

hypoactive sexual desire: a

diagnostic challenge. Psychiatr

Med 1992;10:273281.

Crenshaw TL, Goldberg JP, Stern

27.

28.

29.

30.

31.

32.

33.

34.

WC. Pharmacologic modification of

psychosexual dysfunction. J Sex

Marital Ther 1987;13:239252.

Morales A, Heaton JP. Hormonal

erectile dysfunction. Evaluation

and management. Urol Clin North

Am 2001;28:279288.

Waxenberg SE, Drellich MG,

Sutherlamd AM. The role of

hormones in human behavior. I.

Changes in female sexuality after

adrenalectomy. J Clin Endocrinol

Metab 1959;19:193202.

Basson R. Androgen replacement

for women. Can Fam Physician

1999;45:21002107.

Guay AT, Jacobson J. Decreased

free testosterone and

dehydroepiandrosterone-sulfate

(DHEA-S) levels in women with

decreased libido. J Sex Marital

Ther 2002;28(Suppl 1):129142.

Arlt W, Callies F, van Vlijmen JC, et

al. Dehydroepiandrosterone

replacement in women with

adrenal insufficiency. N Engl J

Med 1999;341:10131020.

Walsh KE, Berman JR. Sexual

dysfunction in the older woman: an

overview of the current

understanding and management.

Drugs Aging 2004;21:655675.

Segraves R, Clayton A, Croft H, et

al. Bupropin sustained release for

the treatment of sexual desire

disorder in premenopausal women.

J Clin Psychopharmacol

2004;3:339342.

OCarroll R, Bancroft J.

Testosterone therapy for low

sexual interest and erectile

dysfunction in men: a controlled

study. Br J Psychiatry

1984;145:146151.

[JUNE]

Psychiatry 2008

55

Você também pode gostar

- Overcoming Sexual Deficiency: A Comprehensive Guide to Restoring IntimacyNo EverandOvercoming Sexual Deficiency: A Comprehensive Guide to Restoring IntimacyAinda não há avaliações

- Sexuality and Sexual DisordersDocumento13 páginasSexuality and Sexual DisordersCharmaigne Aurdane PajeAinda não há avaliações

- Decoding Male Sexual Disorders: A Comprehensive Guide for Patients and PartnersNo EverandDecoding Male Sexual Disorders: A Comprehensive Guide for Patients and PartnersAinda não há avaliações

- Icu BookDocumento140 páginasIcu BookRaMy “MhMd” ElaRabyAinda não há avaliações

- Power BI AssignmentDocumento147 páginasPower BI AssignmentAditya SharmaAinda não há avaliações

- Medical Record StaffDocumento84 páginasMedical Record StaffTuan DzungAinda não há avaliações

- List of DisordersDocumento4 páginasList of DisordersRain Simonette GuanAinda não há avaliações

- Maternal Mortality Rates Report For 2022Documento5 páginasMaternal Mortality Rates Report For 2022ABC Action NewsAinda não há avaliações

- Nonoperating Room Anesthesia Anesthesia in The Gastrointestinal SuiteDocumento16 páginasNonoperating Room Anesthesia Anesthesia in The Gastrointestinal SuiteGustavo ParedesAinda não há avaliações

- Sexual DisordersDocumento18 páginasSexual DisordersKadek Fabrian KhamandanuAinda não há avaliações

- Poverty & Sex TraffickingDocumento11 páginasPoverty & Sex TraffickingBryan GraczykAinda não há avaliações

- 06 Addictive and Sexual DisordersDocumento58 páginas06 Addictive and Sexual DisordersSteven T.Ainda não há avaliações

- Social Work and Resouces Development in Malaysia PDFDocumento76 páginasSocial Work and Resouces Development in Malaysia PDFErmanita AnikAinda não há avaliações

- Social Work Practice With DisabilityDocumento34 páginasSocial Work Practice With DisabilityNamrata SinhaAinda não há avaliações

- Sex Trafficking EssayDocumento11 páginasSex Trafficking EssayInked LacunaAinda não há avaliações

- Anggota BadanDocumento1 páginaAnggota BadanAinurNazuraAinda não há avaliações

- Welcome To N.G Acharya and D.K. Maratha College: - Aditya NashteDocumento5 páginasWelcome To N.G Acharya and D.K. Maratha College: - Aditya NashteTHE ELECTRONIC SQUADAinda não há avaliações

- CATIE Trial Summary PaperDocumento14 páginasCATIE Trial Summary PaperNim RodAinda não há avaliações

- Diabetic Foot Ulcer ClinicalDocumento28 páginasDiabetic Foot Ulcer Clinicaladharia78Ainda não há avaliações

- Anesthesia and Sedation Outside ofDocumento9 páginasAnesthesia and Sedation Outside ofPutriRahayuMoidadyAinda não há avaliações

- Sexual DysfunctionDocumento14 páginasSexual DysfunctionMik Leigh CruzAinda não há avaliações

- Pharmacology of Sexually Compulsive BehaviorDocumento9 páginasPharmacology of Sexually Compulsive Behaviorsara_vonAinda não há avaliações

- SHypo Active Sexual Desire DisorderDocumento74 páginasSHypo Active Sexual Desire Disorderimdad MagfurAinda não há avaliações

- Psychiatric Medicine II The Sexual Disorders Meg Kaplan, PH.DDocumento10 páginasPsychiatric Medicine II The Sexual Disorders Meg Kaplan, PH.DPradeep100% (1)

- Nzomo Elijah MutuaDocumento6 páginasNzomo Elijah MutuaElijahAinda não há avaliações

- 3.-Func y Disf Sex FemeninaDocumento15 páginas3.-Func y Disf Sex FemeninaCristina Bravo100% (1)

- Factors of Sexual DysfunctionDocumento5 páginasFactors of Sexual Dysfunctionaftab khanAinda não há avaliações

- Female Sexual Dysfunction - Sexual Pain DisordersDocumento44 páginasFemale Sexual Dysfunction - Sexual Pain DisordersDian Wijayanti100% (1)

- Sexuality in Older AdultDocumento10 páginasSexuality in Older AdultNisa100% (1)

- ReportDocumento10 páginasReportCindy Mae CamohoyAinda não há avaliações

- Psychosexual DisordersDocumento12 páginasPsychosexual DisordersEJ07100% (1)

- Sexuality and Its Disorders - 1Documento21 páginasSexuality and Its Disorders - 1Adepeju Adedokun AjayiAinda não há avaliações

- How Does Premature Ejaculation Impact A Man S LifeDocumento11 páginasHow Does Premature Ejaculation Impact A Man S LifeSubham TalukdarAinda não há avaliações

- Female Sexual: Assessing & ManagingDocumento8 páginasFemale Sexual: Assessing & ManagingJazmin GarcèsAinda não há avaliações

- Psychiatry SeminarDocumento152 páginasPsychiatry SeminarMichael GebreamlakAinda não há avaliações

- Sexual and Gender Identity DisorderDocumento13 páginasSexual and Gender Identity DisorderWillington ShinyAinda não há avaliações

- Sexual Disorders or Sexual Dysfunction: Linda C. Shafer, M.DDocumento14 páginasSexual Disorders or Sexual Dysfunction: Linda C. Shafer, M.DNur AzizaAinda não há avaliações

- To TransgenderHealth 2015Documento4 páginasTo TransgenderHealth 2015kiki leungAinda não há avaliações

- HypersexualityDocumento7 páginasHypersexualitysuzyAinda não há avaliações

- Lecture 6 Part 2Documento35 páginasLecture 6 Part 2Natia Badridze100% (1)

- Psychosexual DisordersDocumento22 páginasPsychosexual DisordersMaria Zamantha GatchalianAinda não há avaliações

- Female Sexual DysfunctionDocumento18 páginasFemale Sexual DysfunctionRisky SetiawanAinda não há avaliações

- Write Up On Aphrodisiac by Sanusi OluwagbotemiDocumento41 páginasWrite Up On Aphrodisiac by Sanusi OluwagbotemiOLUWAGBOTEMI SANUSIAinda não há avaliações

- Psychosexual DisordersDocumento7 páginasPsychosexual Disordersvivek100% (1)

- By: DR Aini SimonDocumento54 páginasBy: DR Aini SimonRusman BustamanAinda não há avaliações

- Treatment of Sexual DysfunctionDocumento70 páginasTreatment of Sexual DysfunctionCeleste Velasco100% (4)

- Sexual Dysfunctions Self StudyDocumento6 páginasSexual Dysfunctions Self StudymelissagoldenAinda não há avaliações

- Abnormal Psychology IiDocumento3 páginasAbnormal Psychology Iipujitha7122Ainda não há avaliações

- SLP MM20705 Psychosexual Disorders 2019.3.17 PDFDocumento7 páginasSLP MM20705 Psychosexual Disorders 2019.3.17 PDFBrandonRyanF.MosidinAinda não há avaliações

- Antidepressants and Sexual DysfunctionDocumento15 páginasAntidepressants and Sexual DysfunctionGe NomAinda não há avaliações

- Sexual Dysfunctions, Paraphilic Disorders & Gender DysphoriaDocumento23 páginasSexual Dysfunctions, Paraphilic Disorders & Gender DysphoriaJosh Polo100% (3)

- Sexual & Gender Identity DisordersDocumento41 páginasSexual & Gender Identity Disordersrmconvidhya sri2015Ainda não há avaliações

- SexdysguidDocumento19 páginasSexdysguidhitchbashaAinda não há avaliações

- Factsheet: Low Libido (Sexual Desire)Documento1 páginaFactsheet: Low Libido (Sexual Desire)vdphbfiuAinda não há avaliações

- Phases of The Sexual Response CycleDocumento7 páginasPhases of The Sexual Response CyclesimonAinda não há avaliações

- Nejmcp1008161.Pdf - Care of Transsexual PersonsDocumento7 páginasNejmcp1008161.Pdf - Care of Transsexual PersonsCarol RochaAinda não há avaliações

- Sexual Problems EssayDocumento2 páginasSexual Problems EssayPAMELA CLAUDIA SORIAAinda não há avaliações

- Sexual & Gender Identity DisordersDocumento42 páginasSexual & Gender Identity DisordersVikas SamotaAinda não há avaliações

- Sexual Disorders FinalllllDocumento35 páginasSexual Disorders FinalllllYohanes Bosco Panji PradanaAinda não há avaliações

- Systemic Rituals in Sexual Therapy by Gary L. SandersDocumento17 páginasSystemic Rituals in Sexual Therapy by Gary L. SandersOlena BaevaAinda não há avaliações

- The Social SelfDocumento7 páginasThe Social SelfPatricia Ann PlatonAinda não há avaliações

- Mental Health Team by Delicia Ann SDocumento3 páginasMental Health Team by Delicia Ann SDelicia SohtunAinda não há avaliações

- An Overview of Sigmund Freud's TheoriesDocumento13 páginasAn Overview of Sigmund Freud's TheoriesChi NguyễnAinda não há avaliações

- Intro Abnormal PsychologyDocumento30 páginasIntro Abnormal Psychology1989920198950% (2)

- Introduction To Cognitive and Physiological Psychology Week1v2Documento33 páginasIntroduction To Cognitive and Physiological Psychology Week1v2Odaine BennettAinda não há avaliações

- Developing Professional CapacityDocumento6 páginasDeveloping Professional Capacityapi-476189522Ainda não há avaliações

- Istrazivanja Moralnog Razvoja I Moralnog PDFDocumento23 páginasIstrazivanja Moralnog Razvoja I Moralnog PDFlejla13Ainda não há avaliações

- 2 - Management of InstructionDocumento15 páginas2 - Management of InstructionMyla Ebillo100% (4)

- Specific Learning DisabilitiesDocumento44 páginasSpecific Learning DisabilitiesNeeti Moudgil100% (1)

- Linda Leonard - The Puella and The Perverted Old ManDocumento12 páginasLinda Leonard - The Puella and The Perverted Old ManIuliana IgnatAinda não há avaliações

- Types of Speech ContextDocumento2 páginasTypes of Speech ContextKatrina Jade Pajo79% (14)

- 01-People - Psychology - CXL Institute PDFDocumento1 página01-People - Psychology - CXL Institute PDFEarl CeeAinda não há avaliações

- Educ1 Module 1Documento10 páginasEduc1 Module 1Kristina Marie lagartoAinda não há avaliações

- AT2 Tivar VictorioDocumento2 páginasAT2 Tivar VictorioVic TivarAinda não há avaliações

- Ed. 421 Ed. PsychologyDocumento7 páginasEd. 421 Ed. PsychologyHari Prasad100% (1)

- Abridged Report Executive SummaryDocumento5 páginasAbridged Report Executive SummaryledermandAinda não há avaliações

- EMDR WorksheetDocumento2 páginasEMDR WorksheetEcaterina IacobAinda não há avaliações

- Empathy, Mimesis, Magic of AlterityDocumento31 páginasEmpathy, Mimesis, Magic of AlterityVinícius Pedreira100% (1)

- What Is Classroom Observation Guide For ReportingDocumento4 páginasWhat Is Classroom Observation Guide For ReportingMark Bryan CervantesAinda não há avaliações

- Running Head: DRIVING MISS DAISY 1Documento11 páginasRunning Head: DRIVING MISS DAISY 1api-216578352Ainda não há avaliações

- The Hearing Voices Movement: Sandra Escher and Marius RommeDocumento9 páginasThe Hearing Voices Movement: Sandra Escher and Marius RommeJavier Ladrón de Guevara MarzalAinda não há avaliações

- Report For Cynefin FrameworkDocumento3 páginasReport For Cynefin FrameworkAlfadzly AlliAinda não há avaliações

- Kormbip 2Documento300 páginasKormbip 2DerickAinda não há avaliações

- CAS 104-Human Relations and Group DynamicsDocumento46 páginasCAS 104-Human Relations and Group DynamicsERVY BALLERASAinda não há avaliações

- 2ND CotDocumento14 páginas2ND CotJessa MolinaAinda não há avaliações

- Exceptional MemoryDocumento9 páginasExceptional MemoryDoina MiruzarAinda não há avaliações

- Burnout in CounselingDocumento54 páginasBurnout in CounselingmokaAinda não há avaliações

- Barrett's TaxonomyDocumento19 páginasBarrett's TaxonomyAlice100% (5)

- PART 1 Health Assessment Lec Prelim TransesDocumento11 páginasPART 1 Health Assessment Lec Prelim TransesLoLiAinda não há avaliações

- Gender ContinuumDocumento3 páginasGender ContinuumTrisha MariehAinda não há avaliações

- Tears of the Silenced: An Amish True Crime Memoir of Childhood Sexual Abuse, Brutal Betrayal, and Ultimate SurvivalNo EverandTears of the Silenced: An Amish True Crime Memoir of Childhood Sexual Abuse, Brutal Betrayal, and Ultimate SurvivalNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (136)

- The Longest Race: Inside the Secret World of Abuse, Doping, and Deception on Nike's Elite Running TeamNo EverandThe Longest Race: Inside the Secret World of Abuse, Doping, and Deception on Nike's Elite Running TeamNota: 5 de 5 estrelas5/5 (59)

- You Can Thrive After Narcissistic Abuse: The #1 System for Recovering from Toxic RelationshipsNo EverandYou Can Thrive After Narcissistic Abuse: The #1 System for Recovering from Toxic RelationshipsNota: 5 de 5 estrelas5/5 (16)

- Unwanted Advances: Sexual Paranoia Comes to CampusNo EverandUnwanted Advances: Sexual Paranoia Comes to CampusNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (22)

- Emotional Abuse: Recovering and Healing from Toxic Relationships, Parents or Coworkers while Avoiding the Victim MentalityNo EverandEmotional Abuse: Recovering and Healing from Toxic Relationships, Parents or Coworkers while Avoiding the Victim MentalityNota: 5 de 5 estrelas5/5 (12)

- The Myth of Repressed Memory: False Memories and Allegations of Sexual AbuseNo EverandThe Myth of Repressed Memory: False Memories and Allegations of Sexual AbuseNota: 3 de 5 estrelas3/5 (6)

- What Is a Girl Worth?: My Story of Breaking the Silence and Exposing the Truth about Larry Nassar and USA GymnasticsNo EverandWhat Is a Girl Worth?: My Story of Breaking the Silence and Exposing the Truth about Larry Nassar and USA GymnasticsNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (40)

- Unbound: My Story of Liberation and the Birth of the Me Too MovementNo EverandUnbound: My Story of Liberation and the Birth of the Me Too MovementNota: 5 de 5 estrelas5/5 (147)

- The Courage to Heal: A Guide for Women Survivors of Child Sexual AbuseNo EverandThe Courage to Heal: A Guide for Women Survivors of Child Sexual AbuseAinda não há avaliações

- Body Language for Women: Learn to Read People Instantly and Increase Your InfluenceNo EverandBody Language for Women: Learn to Read People Instantly and Increase Your InfluenceNota: 5 de 5 estrelas5/5 (1)

- In the Body of the World: A Memoir of Cancer and ConnectionNo EverandIn the Body of the World: A Memoir of Cancer and ConnectionNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (68)

- Dear Professor: A Woman's Letter to Her StalkerNo EverandDear Professor: A Woman's Letter to Her StalkerNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (157)

- QAnon & the #Pizzagates of Hell: Unreal Tales of Occult Child Abuse by the CIANo EverandQAnon & the #Pizzagates of Hell: Unreal Tales of Occult Child Abuse by the CIANota: 3 de 5 estrelas3/5 (2)

- Girls Like Us: Fighting for a World Where Girls Are Not for Sale, an Activist Finds Her Calling and Heals HerselfNo EverandGirls Like Us: Fighting for a World Where Girls Are Not for Sale, an Activist Finds Her Calling and Heals HerselfNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (49)

- Unheard Screams: A True Childhood Horror Story of a CODA Survivor and How She Overcame Her Father's Sexual AbuseNo EverandUnheard Screams: A True Childhood Horror Story of a CODA Survivor and How She Overcame Her Father's Sexual AbuseAinda não há avaliações

- Breaking the Silence Habit: A Practical Guide to Uncomfortable Conversations in the #MeToo WorkplaceNo EverandBreaking the Silence Habit: A Practical Guide to Uncomfortable Conversations in the #MeToo WorkplaceAinda não há avaliações

- I Love You Baby Girl... A heartbreaking true story of child abuse and neglect.No EverandI Love You Baby Girl... A heartbreaking true story of child abuse and neglect.Nota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (7)

- Invisible Abuse - Instantly Spot the Covert Deception and Manipulation Tactics of Narcissists, Effortlessly Defend From and Disarm Them, and Effectively Recover: Deep Relationship Healing and RecoveryNo EverandInvisible Abuse - Instantly Spot the Covert Deception and Manipulation Tactics of Narcissists, Effortlessly Defend From and Disarm Them, and Effectively Recover: Deep Relationship Healing and RecoveryNota: 5 de 5 estrelas5/5 (2)

- Somebody's Daughter: Inside an International Prostitution RingNo EverandSomebody's Daughter: Inside an International Prostitution RingNota: 5 de 5 estrelas5/5 (3)

- Damaged: The Heartbreaking True Story of a Forgotten ChildNo EverandDamaged: The Heartbreaking True Story of a Forgotten ChildNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (131)

- Understanding Sexual Abuse: A Guide for Ministry Leaders and SurvivorsNo EverandUnderstanding Sexual Abuse: A Guide for Ministry Leaders and SurvivorsNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (3)