Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

Relationship Between Gender, Income and Education and Self-Perceived Oral Health Among Elderly Mexicans. An Exploratory Study

Enviado por

Taufiqurrahman Abdul DjabbarDescrição original:

Título original

Direitos autorais

Formatos disponíveis

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Relationship Between Gender, Income and Education and Self-Perceived Oral Health Among Elderly Mexicans. An Exploratory Study

Enviado por

Taufiqurrahman Abdul DjabbarDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

DOI: 10.1590/1413-81232015204.

00702014

Relao entre gnero, renda e educao com a autopercepo

da sade bucal em idosos mexicanos. Um estudo exploratrio

Rosa Diana Hernndez-Palacios 1

Velia Ramrez-Amador 2

Edgar Carlos Jarillo-Soto 2

Mara Esther Irigoyen-Camacho 2

Vctor Manuel Mendoza-Nez 1

Unidad de Investigacin

en Gerontologa, Facultad

de Estudios Superiores

Zaragoza, Universidad

Nacional Autnoma de

Mxico. Av Guelatao 66,

Iztapalapa, Ejrcito de

Oriente. 09230 Ciudad

de Mxico Mxico.

mendovic@unam.mx

2

Universidad Autnoma

Metropolitana-Xochimilco.

1

Abstract The aim of this study was to identify the relationship between sociodemographic

factors and self-perceived oral health (SPOH)

among the elderly. A cross-sectional, exploratory

examination of 150 elderly subjects whose ages

ranged from 60-86 was conducted. These subjects

used the Geriatric Oral Health Assessment Index

(GOHAI) to assess their SPOH. In addition, sociodemographic data were collected from study

participants. Data were analyzed using Students

t-test, the examination of odds ratio (OR) of logistic regression analysis, the chi-square test, and

analysis of variance (ANOVA). The mean decayed, missing, and filled teeth (DMFT) index for

the study participants was 20.1 5.8; 21.3% of

subjects were edentulous, and 69.3% of subjects

wore removable dentures. 62.7% of study participants had poor SPOH (defined as GOHAI score

<44). Poor SPOH was significantly more frequent

among males (OR = 2.72, 95% CI: 1.03-7.13, p

< 0.05), low-income individuals (OR = 2.7, 95%

CI: 1.3 -5.8, p < 0.01), and subjects with less education (OR = 2.26, 95% CI: 1.1-4.6, p < 0.05)

than among the overall subject population. The

findings suggest that gender (male), low income

and low educational levels have a significant influence on the self-perceived oral health status of

elderly individuals, irrespective of tooth loss.

Key words Oral health, Gender, Income, GOHAI

Resumo O objetivo deste estudo foi identificar a

relao entre os fatores sociodemogrficos com a

autopercepo da sade bucal (SPOH) em idosos.

Realizou-se um estudo transversal exploratrio de

150 idosos. Para avaliar a sua percepo da sade

bucal utilizou-se o Geriatric Oral Assesment Index (GOHAI) e tambm foram coletados dados

sociodemogrficos. Os dados foram analisados

utilizando o teste T Student, a razo de chances

(OR) de anlise de regresso logstica, o teste Chi

Quadrado (p < 0.05) e anlise de varincia ANOVA. A mdia do ndice de dentes cariados, perdidos ou obturados (CPO-D) dos participantes no

estudo foi de 20.1 5.8; 21.3% foram edntulos

e 69.3% eram portadores de prtese removvel.

O 62.7% dos participantes no estudo teve pobre

autopercepo da sade bucal (definida com uma

suma de GOHAI < 44), a qual foi significativamente mais frequente nos homens (OR = 2.72,

95% Cl: 1.03-7.13, p < 0.05), com baixa renda

(OR = 2.7, 95% Cl: 1.3 5.8, p < 0.01), e com

menor escolaridade (OR = 2.26, 95% Cl: 1.1-4.6,

p <0.05) do que entre a populao em geral. Os

resultados presentes sugerem que nos idosos a baixa renda e a menor escolaridade tm influncia

significativa na autopercepo da sade bucal, independentemente da perda dentria.

Palavras-chave Sade bucal, Gnero, Renda,

GOHAI

ARTIGO ARTICLE

Relationship between gender, income and education

and self-perceived oral health among elderly Mexicans.

An exploratory study

997

Hernndez-Palacios RD et al.

998

Introduction

Oral health and its self-perception are linked

to the life quality of older people, which is

influenced by socio demographic factors, such

as gender, income and education1,2. In this

sense, most individuals belonging to this social

group not only live in poverty and experience

marginalization and social inequality but

also frequently lack access to health services;

moreover, chronic and degenerative diseases

abound among this vulnerable group of

individuals3. These afflictions include mouth

diseases, which are regarded as a public health

problem because of their high prevalence and

incidence, with caries and periodontal disease as

the leading causes of tooth loss4,5.

Oral health status has traditionally been

assessed by objective clinical criteria; however,

it has become necessary to consider particular

subjective aspects of oral health to attain a more

comprehensive understanding of relevant health

and disease processes. A questionnaire known as

the GOHAI (Geriatric Oral Health Assessment

Index), which was developed by Atchison and

Dolan, has been used to measure the selfperceived oral health (SPOH) statuses of elderly

individuals6-8.

This instrument has been validated in several

languages and countries for the assessment

of the functional, psychological, and social

impact of oral conditions on daily life in various

sociocultural contexts and the determination of

the oral health needs of elderly populations9-13.

Several studies have addressed the factors that

affect SPOH. In such regard, it was found that

education and gender were factors associated

with poor SPOH14. Similarly, it has been revealed

that higher income was associated with better

SPOH15,16. Thus, the aim of this study was to

identify socio demographic factors associated

with self-perceived oral health (SPOH) among

elderly subjects.

Methods

Previous informed consent, an exploratory crosssectional study was carried out in a convenience

sample of 150 adults (of both genders) that

met the following criteria: (a) interest in

participating in the study; (b) literate; (c) absence

of handicapping illnesses or serious visual or

auditory disabilities. These subjects were selected

from 300 elderly adults who regularly attended a

public recreation center in the eastern portions

of Mexico City. The investigation protocol

was approved by the Ethics Committee of the

Universidad Nacional Autnoma de Mxico

(UNAM) Zaragoza Campus.

Self-perceived oral health (SPOH)

SPOH was assessed by administering the

Spanish version of the GOHAI questionnaire,

which was validated in Mexican older people.

This questionnaire assesses the following three

dimensions: the psychosocial dimension, which

relates to satisfaction with the appearance of

teeth, oral health concerns, and social networking

limitations caused by oral problems; the physical

dimension, which relates to the functions of

eating, speaking, and swallowing; and the pain or

discomfort dimension, which includes the use of

medications to treat oral health problems16.

The GOHAI questionnaire includes 12

oral health-related questions. Each item of the

questionnaire is scored using the following

Likert scale: 0, never; 1, rarely; 2, sometimes; 3,

often; 4, very often; and 5, always. The scores for

questions 3, 5, and 7 are encoded in reverse order.

We did an analysis of percentiles, and it was

established as cutoff point the value of the first

quartile ( 44 score) for poor SPOH statuses

and third quartile (GOHAI 51 score) for good

SPOH.

Sociodemographic variables

A questionnaire was administered to the study

subjects to assess the following sociodemographic

variables: age, sex, marital status, education,

income, and the identities of other persons living

with the subject. Subjects were classified into the

following three age categories: 60-69 years, 70-79

years, and > 80 years. With respect to education,

subjects were classified into the following three

categories based on the number of years of

schooling they had received: 0-6 years, 7-9 years,

and > 9 years. On the other hand, we did an

analysis of percentiles related to income, and it

was established as cutoff point the value of the

first quartile ( US$154) for lower income.

Oral health status

After this questionnaire had been

administered to the subjects, an oral examination

was performed in which a light source and plane

mirror were used to evaluate the oral health

999

Statistical Analysis

Data were analyzed with the SPSS 16.0

statistical software package, which was used to

obtain descriptive statistics for the study variables.

Students t-test and analysis of variance (ANOVA)

were used to determine the statistical significance

of quantitative variables, and the chi-square test

with a 95% confidence level was used to assess

qualitative variables. Odds ratios (ORs) of logistic

regression analysis with their associated 95%

confidence intervals (CIs) were used to calculate

risk estimates, were considering as independent

variables (age, gender, income, live alone,

schooling, DMFT, uses dentures, and tooth loss)

and possible risk factors for poor SPOH statuses

( 44). An OR > 1 and the associated CI did not

include 1 (p < 0.05) was considered as risk factor.

Results

The study involved a total of 150 participants,

including 119 (79.3%) women and 31 (20.7%)

men. The mean age of the study subjects was

67 6.4 years. In addition, 76 (50.6%) study

participants were married, 53 (35.3%) study

participants were widowed, and 62 (41.3%)

study participants lived with their children.

With respect to education, 86 (57.4%) study

subjects reported that they had six or fewer

years of schooling; with respect to income,

63 (42%) study subjects reported having a

monthly income of no more than US$154.

The mean value of the overall DMFT index for

the study subjects, which described the general

oral health status of the examined population,

was 20.1 5.8. The following mean values were

observed for specific components of the DMFT

index: 5.6 5.4 for sound teeth, 1.5 2.0 for

decayed teeth, 6.5 5.6 for filled teeth, and

12.0 8.6 for missing teeth. Notably, 51% of

study participants (77 subjects) had ten or more

missing teeth, and 21.3% (32 subjects) of study

participants were edentulous (i.e., these subjects

had lost all of their teeth).

The mean GOHAI score for the study

subjects was 46.5 8.1, with a minimum score

of 25 and a maximum score of 60. GOHAI scores

were significantly lower among the group of

low-income elderly individuals than among the

medium- to high-income group of study subjects

(41.5 9.9 versus 45.8 10.5, p < 0.01). GOHAI

scores did not significantly differ for subjects of

different genders (44.5 11.3 (for male) versus

43.8 10.2 (for female), p > 0.05) (Table 1).

With respect to SPOH, poor, normal, and

good SPOH statuses were reported by 94 (62.6%),

42 (28.0%), and 14 (9.3%) of the elderly subjects

of this study, respectively. The classification of

study participants by gender revealed that 69.8%

of female study subjects and 35.5% of male study

subjects had poor SPOH (Table 2).

Table 3 indicates the distribution of responses

received from the elderly study subjects for each

question of the GOHAI questionnaire. Notably,

66% (99) of the study participants reported

problems with chewing, 90.6% (136) of the

study participants reported discomfort when

eating, 84% (126) of the study participants were

unhappy with the appearance of their teeth, and

64% (96) of the study participants were required

to alter the types of food they consumed because

of problems with their teeth or dentures.

With respect to the risk factors associated

with poor SPOH (GOHAI score 44), poor

SPOH statuses were significantly more frequent

among male subjects (OR = 2.72, 95% CI: 1.037.13, p < 0.042), low-income subjects (OR = 2.7,

95% CI: 1.3-5.8, p < 0.007), and subjects with

lower education levels (OR = 2.26, 95% CI: 1.14.6, p < 0.02) than among the entire population

of study subjects. Also, high tooth loss 12 teeth)

was risk factor for poor SPOH (OR = 16.9, 95%

CI: 6.6-42.7, p < 0.04) (Table 4).

Discussion

Major oral health problems experienced

by elderly individuals include dental caries,

periodontal disease, and disorders related to the

prolonged and improper use of dentures18-20.

Moreover, assessments of SPOH among elderly

subjects have revealed that > 80% of elderly

individuals have concerns regarding their oral

health and/or poor SPOH status11,21,22. This

phenomenon cannot be attributed merely to

Cincia & Sade Coletiva, 20(4):997-1004, 2015

status of the elderly study participants. This

examination was conducted by a female dentist

who was previously standardized to perform the

measurements, obtaining a Kappa value of 0.85.

In accordance with World Health Organization

(WHO) criteria, dental caries were assessed using

the decayed, missing, and filled teeth (DMFT)

index, which accounts for teeth that are decayed,

missing, filled by restorative dental work, and

healthy17. The denture-wearing practices of the

elderly study participants were also recorded.

Hernndez-Palacios RD et al.

1000

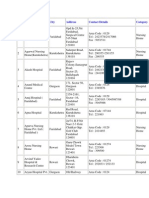

Table 1. GOHAI score related to sociodemographic

characteristics.

Variables

n = 150

Age (years)

60-69

70-79

> 80

Gender

Male

Female

Education (years)

0-6

7-9

>9

Monthly income

US$154

> US$154

Marital status

Married

Widowed

Divorced

Single

Living with

Nobody

Husband/wife

Children

Husband/wife/children

Others

GOHAI score

p

0.95

98

45

7

65.3 46.77 8.46

30.0 46.31 8.14

4.7 46.57 7.95

31

119

20.7 44.58 11.3

79.3 43.88 10.2

86

32

32

57.4 43.06 10.6

21.3 44.44 10.7

21.3 46.22 9.5

63

87

42.0 41.52 9.9

58.0 45.84 10.5

76

53

16

5

50.6 47.12 10.1

35.3 40.60 10.1

10.7 46.05 8.3

3.4 44.60 11.9

21

35

62

28

4

14.0

23.3

41.3

18.7

2.7

0.077

0.33

0.012*

0.03**

0.15

43.19 10.5

47.06 10.2

44.32 9.86

41.11 11.5

37.75 10.3

GOHAI, General Oral Health Assessment Index. Data are presented as

means SD. * Students t-test,** ANOVA.

Table 2. SPOH status frequencies among elderly Mexicans by

sex.

Gender

Good

51

Female (%)

Male (%)

Total (%)

9 (7)

5 (16)

14 (9)

Normal

45-50

27 (23)

15 (48)

42 (28)

Poor

44

Total

83 (70)

11 (36)

94 (63)

119 (100)

31 (100)

150 (100)

SPOH, self-perceived oral health.

age; in particular, a report from Latin America

has indicated that more than 70% of examined

institutionalized elderly individuals exhibited

good SPOH statuses22. In combination, the

aforementioned findings suggest that living

conditions, sociocultural characteristics, and

the availability of health services are important

determinants of SPOH.

In the current study, a relationship was

observed between sociodemographic conditions

and SPOH among the examined elderly subjects;

for instance, risk factors for poor SPOH included

a low income and a low educational level. These

findings are similar to the results reported by

Brennan & Spencer23, who found that poor SPOH

is related to income and to a low educational

level. Similarly, Lpez Soto et al.24 found that

individuals with poor SPOH also tended to have

low educational levels. Likewise, Tsakos et al.25 in

a study with community-dwelling non-disabled

people 65 yr of age and older, from suburban

London found that the low educational level

has an independent negative impact on poor

SPOH; and de Andrade et al.26 observed that

sufficient income and higher schooling ( years

8) are associated with significantly better GOHAI

scores in elderly Brazilians; also Fuentes-Garca et

al.27 found similar results in community-dwelling

older people of three cities in South America

(Santiago, Chile; Buenos Aires, Argentina and

Montevideo, Uruguay).

These findings suggest that individuals

with low incomes and low educational levels

must first satisfy their basic needs, such as food,

clothing, and transportation, before addressing

oral health; thus, oral health may be a relatively

low priority among low-income, relatively

uneducated elderly individuals. On the other

hand, it is necessary to assess lifestyles associated

with cultural characteristics linked to oral

health care; for instance, several participants

in the current study stated that when they

were children, their families not only lacked

the toothbrushes and toothpaste required for

practicing good oral hygiene but also ignored

the importance of keeping their teeth in good

condition. These study participants could not

access health services and did not receive timely

dental care for the detection of oral problems.

Thus, these individuals only sought medical care

after oral pathological processes had reached

an advanced stage; given that conservative

treatments are generally expensive, they typically

chose the option of dental extraction, leading to

the gradual loss of teeth observed to be associated

with poor SPOH.

In this study, we observed a higher frequency

of poor SPOH (GOHAI score 44) in the male

group. This finding contrasts with the results

reported by Locker & Slade8 who observed that

oral health and pain issues are a greater concern

for female gender than for male; this suggests that

gender-related sociocultural characteristics may

be determinants of individuals lifestyles with

respect to oral health, function, and aesthetics.

1001

GOHAI dimensions

Physical function

Food limitations

Chewing problems

Swallow easily

Speaking problems

Pain and discomfort

Discomfort when eating

The use of relevant medications

Dental pain with hot/cold stimuli

Psychological impact

Unhappy with appearance

Worried about teeth

Nervous about teeth

Uncomfortable eating with others

Avoid contact with people

Always

n (%)

Often

n (%)

27 (18.0)

32 (21.3)

85 (56.7)

14 (9.3)

27 (18.0)

25 (16.7)

12 (8.0)

22 (14.7)

50 (33.3)

1 (0.7)

3 (2.0)

36 (24.0)

41 (27.3)

10 (6.7)

10 (6.7)

3 (20)

Table 4. Factors associated with poor self-perceived

oral health (GOHAI 44).

Factor

OR

95% CI

Age ( 69 years)

0.6 0.3-1.2

Sex (male)

2.7 1.0-7.1

Income ( US$154/month) 2.7 1.3 -5.8

Live alone

0.5 0.3-0.7

Schooling ( 6 years)

2.2 1.1-4.6

DMFT ( 14)

0.8 0.3-2.1

Uses dentures

3.0 0.8-10.3

Tooth loss ( 12 teeth)

16.9 6.6-42.7

p-value

0.15

0.042

0.007

0.001

0.024

0.81

0.07

0.04

OR, Odds ratio. Logistic regression analysis.

In addition, results from the current study

indicated that married subjects reported better

SPOH levels than unmarried subjects. This

finding is consistent with observations by

Kressin et al.28, who concluded that married

subjects exhibited high GOHAI scores. These

results suggest that individuals with partners

will devote greater attention to their oral health

than individuals without partners because the

partnered individuals must please or at least live

with another person and will therefore engage

in higher levels of personal care in general and

health care in particular.

Based on the cutoff thresholds established

for Anglo-Saxon populations, the mean GOHAI

score obtained in the present study (46.5 8.1)

Sometimes

n (%)

Rarely

n (%)

Never

n (%)

17 (1.3)

21 (14.0)

29 (19.3)

20 (13.3)

25 (16.7)

21 (14.0)

13 (8.7)

23 (15.3)

54 (36.0)

51 (34.0)

11 (7.3)

71 (47.3)

34 (22.7)

0 (0.0)

8 (5.3)

27 (18.0)

9 (6.0)

17 (11.3)

25 (16.7)

44 (29.3)

28 (18.7)

14 (9.3)

96 (64.0)

94 (62.7)

35 (23.3)

24 (16.0)

22 (14.7)

22 (14.7)

16 (10.7)

31 (20.7)

27 (18.0)

39 (26.0)

25 (16.7)

27 (18.0)

24 (16.0)

29 (19.3)

22 (14.7)

29 (19.3)

31 (20.7)

24 (16.0)

29 (19.3)

57 (38.0)

64 (42.7)

73 (48.7)

corresponds to poor SPOH6. However, this mean

GOHAI score is similar to not only the mean

GOHAI score (45.84 7.0) observed in a study of

institutionalized elderly Mexican subjects16 but

also the mean GOHAI score (42.6) obtained in a

Chilean study15. These findings suggest that poor

oral health among elderly individuals in Latin

America is a consequence of economic conditions

and a lack of access to dental health services;

these issues lead to the deterioration of their oral

health and consequently produce poor SPOH.

In this study, measurements using the DMFT

index indicated that dental care greatly impacted

oral health. For the examined subjects, a mean

DMFT value of 20.1 affected teeth was obtained;

the major component of this DMFT value was

missing teeth, with an average of 12 teeth missing

per study participant. In this sense, several studies

have reported that the tooth loss in a predictor of

poor cognitive function in community-dwelling

adults older29-31. On the other hand, Zuluaga et

al.32 found a significantly better GOHAI scores

in elderly with mild cognitive impairment

(MCI) than cognitively normal residents in nine

geriatric institutions in the Spanish province of

Granada. Therefore suggest administer cognitive

screening combined with applying any OH-QoL

instrument would make the results more reliable.

Thus, we can assert that elderly experience

a high magnitude and severity of dental caries,

a phenomenon that is associated with living

conditions and with limited access to dental health

services. Therefore, it is urgent to implement

Cincia & Sade Coletiva, 20(4):997-1004, 2015

Table 3. Distribution GOHAI items across Likert scale.

Hernndez-Palacios RD et al.

1002

programs to promote oral health in the context

of active aging33,34, that incorporate preventive

practices and timely dental care at the community

level and can thereby forestall irreversible

dental damage and subsequent tooth loss.

In addition, this study found that 21.3% of the

examined elderly subjects were edentulous.

In such regard, it has been observed that

the rates of edentulism differ in each ethnic

group, which is determined by conditions and

life styles35,36. Notably, the high incidence of

edentulism has been erroneously regarded as a

normal aging-related change.

Most dental treatments received by lowincome elderly are crippling in nature because

these treatments are less expensive than

more conservative approaches. Thus, these

treatments affect biological, psychological, and

social domains and thereby influence SPOH.

In accordance with this reasoning, TrejoJuarz et al.11 observed an inverse relationship

between DMFT scores and positive psychosocial

perceptions.

Overall, the results of our study demonstrate

an inverse association between GOHAI score and

tooth loss. In particular, our findings showed

that elderly subjects with more than 12 missing

teeth are more likely to have poor SPOH statuses.

It has been observed a relationship between

the oral health status with the difficulties in

acquiring and preparing food; these difficulties,

in combination with social abandonment issues,

a diminished support network, and psychological

problems such as depression, can exacerbate the

nutritional problems of elderly individuals37.

The results of the current study also indicated

that because the ability of edentulous elderly

individuals to chew correctly is determined

by denture function, the use of an ill-fitting

denture is associated with poor SPOH among

the examined elderly subjects. Moreover, it was

determined that dentures worn by elderly adults

were frequently damaged and ill-fitting due to

long use and a lack of a periodic examination of

denture fit by a dentist. Importantly, the study

participants who used dental dentures generally

exhibited poor SPOH statuses; this phenomenon

could be caused by a lack of appropriate followup to ensure that dentures fit correctly. In this

sense, Albaker38 found that the mean GOHAI

score was significantly lower (p < 0.05) among

participants who had conventional denture

on both upper and lower jaw (28.25 3.67),

as compared to those who had conventional

denture only on one arch.

Among the limitations of the current study, we

emphasize that this research is a cross-sectional

study with a convenience sample, the percentage

of women was significantly higher than men

and age 60 to 69 years group was significantly

more numerous, hence is not representative; we

suggest that a longitudinal study with a large

representative sample of individuals both sexes,

more age groups, and different contexts should

be conducted to confirm our findings.

Conclusion

The elderly are considered to be a vulnerable

group because of their living conditions

frequently deteriorate over time. Our study

demonstrated that poor SPOH is associated with

gender (male), low income and low educational

level, independently and poor oral health. SPOH

affects not only functional and psychological

characteristics but also social relationships.

Therefore, the living conditions of elderly adults

must be improved, and preventive programs for

active aging that can prevent tooth loss and the

associated biological, psychological, and social

consequences must be developed.

1003

References

RD Hernandez-Palacios participated in the

design of this study and the collection, analysis,

and interpretation of study data. EC JarilloSoto participated in the development of study

concepts and the drafting of the paper. ME

Irigoyen-Camacho participated in data analysis.

V Ramirez-Amador participated in the design of

the study. M Mendoza-Nez participated in the

analysis and interpretation of study data and the

drafting of this paper.

1.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by Direccin General

de Asuntos del Personal Acadmico, Universidad

Nacional Autnoma de Mxico (DGAPA, UNAM).

2.

3.

4.

5.

6.

7.

8.

9.

10.

11.

12.

13.

14.

15.

16.

Skaar DD, Hardie NA. Demographic factors associated with dental utilization among community dwelling

elderly in the United States, 1997. J Public Health Dent

2006; 66(1):67-71.

Skaar DD, OConnor H. Dental service trends for

older US adults, 1998-2006. Spec Care Dentist 2012;

32(2):42-48.

Wong R, Espinoza M, Pallono A. Adultos mayores

mexicanos en contexto socioeconmico amplio: salud

y envejecimiento. Salud Publica de Mex 2007; 49(Supl.

4):S436- S447.

Soto-Smano C, Rubio-Cisneros J, Taboada-Aranza

O, Mendoza-Nez VM. Patologa bucal en el senecto: un estudio exploratorio. Dentista y Paciente 1998;

7(74):20-26.

Irigoyen ME, Velzquez C, Zepeda M, Meja A. Caries

dental y enfermedad periodontal en un grupo de personas de 60 aos o ms de edad de la ciudad de Mxico.

Rev ADM 1999; 44(2):64-69.

Atchison KA, Dolan TA. Development of the Geriatric Oral Health Assessment Index. J Dent Educ 1990;

54(11):680-687.

Locker D. Clinical correlates of changes in self-perceived oral health in older adults. Community Dent

Oral Epidemiol 1997; 25(3):199-203.

Locker D, Slade G. Association between clinical and

subjective indicators of oral health status in an older

adult population. Gerodontology 1999; 11(2):108-114.

Arlette S, Zunzunegui MV. Deteccin de necesidades

de atencin bucodental en ancianos mediante la autopercepcin de la salud oral. Rev Multidisciplinaria de

Gerontologa 1999; 9(4):216-224.

Tubert-Jeannin S, Riordan P, Morel-Papermot A,

Porcheray S, Saby-Collet S. Validation of an oral health

quality of life index (GOHAI) in France. Community

Dent Oral Epidemiol 2003; 31(4):275-284.

Trejo-Jurez EP, Rangel-Aldama R, Martnez-Zambrano IA, Hernndez-Palacios RD, Mendoza-Nez VM.

Relacin entre el ndice de caries dental (CPOD) con

la percepcin psicosocial en una poblacin de adultos

mayores. Rev Archivos de Geriatra 2004; 71(6):17-20.

Naito M, Suzukamo Y, Nakayama T, Hamajima N,

Fukuhara S. Linguistic adaptation and validation of

the General Oral Health Assessment Index (GOHAI)

in an elderly Japanese population. J Public Health Dent

2006; 66(4):273-275.

Momen A. Arabic version of the geriatric oral health

assessment index. Gerodontology 2008; 25(1):34-41.

Afonso-Souza G, Nadanovsky P, Chor D, Faerstein E,

Werneck GL, Lopes CS. Association between routine

visits for dental checkup and self-perceived oral health

in an adult population in Rio de Janeiro: the PrSade Study. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 2007;

35(5):393-400.

Montes J. Impacto de la salud oral en la calidad de vida

del adulto mayor. Rev Dental de Chile 2001; 92(3):2931.

Snchez-Garca S, Heredia-Ponce E, Jurez-Cedillo T,

Gallegos-Carrillo K, Espinel-Bermdez C, de la Fuente-Hernndez J, Garca-Pea C. Psychometric properties of the General Oral Health Assessment Index (GOHAI) and dental status of an elderly Mexican population. J Public Health Dent 2010; 70(4):300-307.

Cincia & Sade Coletiva, 20(4):997-1004, 2015

Collaborations

Hernndez-Palacios RD et al.

1004

17. World Health Organization (WHO). Oral health surveys, indices and methods for measurement of dental disease. 4th ed. Geneva: WHO; 1997.

18. Taboada-Aranza O, Mendoza-Nez VM, MartnezZambrano I. Prevalencia y severidad de la enfermedad

parodontal. Dentista y Paciente. Rev Universidad Tecnolgica de Mxico 2000; 8(9):10-16.

19. Valdez-Penagos G, Mendoza-Nez VM. Relacin del

estrs oxidativo con la enfermedad periodontal en

adultos mayores con diabetes mellitus tipo 2. Rev ADM

2006; 80(5):189-194.

20. Martnez-Zambrano IA, Hernndez-Palacios RD,

Garca-Barrera MJ, Mendoza-Nez VM. Prevalencia

y factores de riesgo de candidosis eritematosa crnica en una poblacin de adultos mayores usuarios de

prtesis dentales totales y removibles. Medicina Oral

2008; 10(1):12-15.

21. Esquivel R, Jimnez J. Necesidades de atencin

odontolgica en adultos mayores mediante la aplicacin del GOHAI. Rev ADM 2010; 67(3):127-132.

22. Piuvezam G, de Lima KC. Self-perceived oral health

status in institutionalized elderly in Brazil. Arch Gerontol Geriatr 2012; 55(1):5-11.

23. Brennan D, Spencer J. Life events and oral health related quality of life among young adults. Qual Life Res

2009; 18(5):557-565.

24. Lpez-Soto OP, Cardona-Rivas D, Parra-Snchez H,

Montes-Rojas DM, Arango-Ossa MA. Morbilidad oral

y factores de riesgo en adultos mayores. Revista Digital

Salud 2005; 1.

25. Tsakos G, Sheiham A, Iliffe S, Kharicha K, Harari D,

Swift CG, Gillman G, Stuck AE. The impact of educational level on oral health related quality of life in older

people in London. Eur J Oral Sci 2009; 117(3):286-292.

26. Andrade FB, Lebro ML, Santos JL, Cruz Teixeira DS,

Oliveira Duarte YA. Relationship between oral health

related quality of life, oral health, socioeconomic, and

general health factors inelderly Brazilians. J Am Geriatr

Soc 2012; 60(9):1755-1760.

27. Fuentes-Garca A, Lera L, Snchez H, Albala C. Oral

health-related quality of life of older people from three

South American cities. Gerodontology 2013; 30(1):6775.

28. Kressin NR, Atchison KA, Miller DR. Comparing the

impact of oral disease in two populations of older

adults: application of the geriatric oral health assessment index. J Public Health Dent 2007; 57(4):224-232.

29. Kaye EK, Valencia A, Baba N, Spiro A 3rd, Dietrich T,

Garcia RI. Tooth loss and periodontal disease predict

poor cognitive function in older men. J Am Geriatr Soc

2010; 58(4):713-718.

30. Park H, Suk SH, Cheong JS, Lee HS, Chang H, Do SY,

Kang JS. Tooth loss may predict poor cognitive function in community-dwelling adults without dementia

or stroke: the PRESENT project. J Korean Med Sci 2013;

28(10):1518-1521.

31. Lexomboon D, Trulsson M, Wrdh I, Parker MG.

Chewing ability and tooth loss: association with cognitive impairment in an elderly population study. J Am

Geriatr Soc 2012; 60(10):1951-1956.

32. Zuluaga DJ, Montoya JA, Contreras CI, Herrera RR.

Association between oral health, cognitive impairment

and oral health-related quality of life. Gerodontology

2012; 29(2):e667-673.

33. Martnez-Maldonado ML, Correa-Muoz E, Mendoza-Nez VM. Program of active aging in a rural Mexican community: a qualitative approach. BMC Public

Health 2007; 7:276.

34. Mendoza-Nez VM, Martnez-Maldonado ML, Correa -Muoz E. Implementation of an active aging model in Mexico for prevention and control of chronic diseases in the elderly. BMC Geriatrics 2009; 9:40.

35. Wu B, Liang J, Plassman BL, Remle C, Luo X. Edentulism trends among middle-aged and older adults in the

United States: comparison of five racial/ethnic groups.

Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 2012; 40(2):145-153.

36. Wu B, Liang J, Landerman L, Plassman B. Trends of

edentulism among middle-aged and older Asian Americans. Am J Public Health 2013; 103(9):e76-82.

37. Snchez-Garca S, Jurez-Cedillo T, Reyes-Morales H,

Fuente-Hernndez J, Solrzano-Santos F, Garca-Pea

C. Estado de la denticin y sus efectos en la capacidad

de los ancianos para desempear sus actividades habituales. Salud Publica Mex 2007; 49(3):173-181.

38. Albaker AM. The oral health-related quality of life in

edentulous patients treated with conventional complete dentures. Gerodontology 2013; 30(1):61-66.

Article submitted 14/06/2014

Approved 01/10/2014

Final version submitted 12/10/2014

Você também pode gostar

- Social Determinants of Health and Knowledge About Hiv/Aids Transmission Among AdolescentsNo EverandSocial Determinants of Health and Knowledge About Hiv/Aids Transmission Among AdolescentsAinda não há avaliações

- Cousson Et Al 2012 GerodontologyDocumento8 páginasCousson Et Al 2012 Gerodontologywiena aviolitaAinda não há avaliações

- Vision Screening for Elementary Schools: The Orinda StudyNo EverandVision Screening for Elementary Schools: The Orinda StudyAinda não há avaliações

- Uoi 142 FDocumento9 páginasUoi 142 FbkprosthoAinda não há avaliações

- Concepto Del Drenaje Linfatico ManualDocumento9 páginasConcepto Del Drenaje Linfatico ManualMontserrat SánchezAinda não há avaliações

- Jenny Abanto, Georgios Tsakos, Saul Martins Paiva, Thiago S. Carvalho, Daniela P. Raggio and Marcelo BöneckerDocumento10 páginasJenny Abanto, Georgios Tsakos, Saul Martins Paiva, Thiago S. Carvalho, Daniela P. Raggio and Marcelo BöneckerTasya AwaliyahAinda não há avaliações

- BrazJOralSci 2013 Vol12 Issue1 p5 10Documento6 páginasBrazJOralSci 2013 Vol12 Issue1 p5 10Taufiqurrahman Abdul DjabbarAinda não há avaliações

- Articol 1Documento10 páginasArticol 1Airam MAinda não há avaliações

- Comparative Oral Health of Children and Adolescents With Cerebral Palsy and ControlsDocumento7 páginasComparative Oral Health of Children and Adolescents With Cerebral Palsy and ControlsVinzAinda não há avaliações

- Paper 229Documento6 páginasPaper 229Tria Sesar AprianiAinda não há avaliações

- Oral Health-Related Quality of Life of Schoolchildren: Impact of Clinical and Psychosocial VariablesDocumento8 páginasOral Health-Related Quality of Life of Schoolchildren: Impact of Clinical and Psychosocial VariablesJuliana MoroAinda não há avaliações

- CDH 4550barasuol05Documento5 páginasCDH 4550barasuol05Deepakrajkc DeepuAinda não há avaliações

- Le N Et Al 2016 GerodontologyDocumento9 páginasLe N Et Al 2016 GerodontologyBrijesh MaskeyAinda não há avaliações

- Proposal FinalDocumento6 páginasProposal FinalYussuf OmarAinda não há avaliações

- 20socioeconomic and ClinicalDocumento9 páginas20socioeconomic and ClinicalAnonymous YC6V8JAinda não há avaliações

- Articol AutismDocumento5 páginasArticol AutismOanaFloreaAinda não há avaliações

- Determinants For Preventive Oral Health Care Need Among Community-Dwelling Older People: A Population-Based StudyDocumento8 páginasDeterminants For Preventive Oral Health Care Need Among Community-Dwelling Older People: A Population-Based StudyIvan CarranzaAinda não há avaliações

- Oral Health-Related Quality of Life, Sense of Coherence and Dental Anxiety: An Epidemiological Cross-Sectional Study of Middle-Aged WomenDocumento6 páginasOral Health-Related Quality of Life, Sense of Coherence and Dental Anxiety: An Epidemiological Cross-Sectional Study of Middle-Aged WomenAlexandru Codrin-IonutAinda não há avaliações

- Jcs 8 105Documento6 páginasJcs 8 105nadia syestiAinda não há avaliações

- Adj 12774Documento5 páginasAdj 12774Irfan HussainAinda não há avaliações

- tmp1F38 TMPDocumento6 páginastmp1F38 TMPFrontiersAinda não há avaliações

- 12 - Media Exposure and Oral Health Outcomes Among AdultsDocumento11 páginas12 - Media Exposure and Oral Health Outcomes Among AdultskochikaghochiAinda não há avaliações

- Scientific Articles: 1. Dalius Petrauskas, Janina Petkeviciene, Jurate Klumbiene, Jolanta SiudikieneDocumento8 páginasScientific Articles: 1. Dalius Petrauskas, Janina Petkeviciene, Jurate Klumbiene, Jolanta SiudikieneChandra Sekhar ThatimatlaAinda não há avaliações

- Final DNH PH Paper 1Documento9 páginasFinal DNH PH Paper 1api-598493568Ainda não há avaliações

- Machado, Fichman - 2009 - Normative Data For Healthy Elderly On The Phonemic Verbal Fluency Task - FAS-annotatedDocumento6 páginasMachado, Fichman - 2009 - Normative Data For Healthy Elderly On The Phonemic Verbal Fluency Task - FAS-annotatedHelena AlessiAinda não há avaliações

- Prevalence, Severity and Associated Factors of Dental Caries in 3-6 Year Old Children - A Cross Sectional StudyDocumento7 páginasPrevalence, Severity and Associated Factors of Dental Caries in 3-6 Year Old Children - A Cross Sectional StudysaravananspsAinda não há avaliações

- Mathur Et Al 2016 GerodontologyDocumento8 páginasMathur Et Al 2016 GerodontologyBrijesh MaskeyAinda não há avaliações

- Gradientes Sociales en El Estado de Salud Bucal en La Población de CoreaDocumento6 páginasGradientes Sociales en El Estado de Salud Bucal en La Población de CoreaStefania Vargas PerezAinda não há avaliações

- 903 1224 2 PBDocumento12 páginas903 1224 2 PBFatul Chelseakers ZhinZhaiAinda não há avaliações

- Oral HealthDocumento50 páginasOral HealthJelena JacimovicAinda não há avaliações

- Orofacial Dysfunction Nonnutritive Sucking Hab 2022 American Journal of OrtDocumento8 páginasOrofacial Dysfunction Nonnutritive Sucking Hab 2022 American Journal of OrtMario Ruiz RuizAinda não há avaliações

- Oral HygieneDocumento9 páginasOral HygieneemeraldwxyzAinda não há avaliações

- International Journal of Pediatric OtorhinolaryngologyDocumento7 páginasInternational Journal of Pediatric OtorhinolaryngologyCristyanlordAinda não há avaliações

- 06 Navin IngleDocumento12 páginas06 Navin IngleFaradhillah KartonoAinda não há avaliações

- Proposal 2Documento4 páginasProposal 2Yussuf OmarAinda não há avaliações

- International Journal of Health Sciences and ResearchDocumento7 páginasInternational Journal of Health Sciences and ResearchNabila RizkikaAinda não há avaliações

- Assessment of Knowledge Regarding Oral Hygiene Among Parents of Pre-School Children Attending Pediatric Out Patient Department in Dhulikhel HospitalDocumento6 páginasAssessment of Knowledge Regarding Oral Hygiene Among Parents of Pre-School Children Attending Pediatric Out Patient Department in Dhulikhel HospitalSri HariAinda não há avaliações

- International Journal of Nursing Studies: Tze-Fang Wang, Chiu-Mieh Huang, Chyuan Chou, Shu YuDocumento7 páginasInternational Journal of Nursing Studies: Tze-Fang Wang, Chiu-Mieh Huang, Chyuan Chou, Shu YuRob21aAinda não há avaliações

- Amirabadi F, Rahimian-Imam S, Ramazani N, Saravani SDocumento5 páginasAmirabadi F, Rahimian-Imam S, Ramazani N, Saravani SABI AGUILAR SERVICOMPCAinda não há avaliações

- Fadila Kemala Dwi Ramadhani Ruslan - Revisi Kbpji 2Documento16 páginasFadila Kemala Dwi Ramadhani Ruslan - Revisi Kbpji 2Eugenia RussiavAinda não há avaliações

- Kumar2016 PDFDocumento7 páginasKumar2016 PDFEtna Defi TrinataAinda não há avaliações

- 2009 - Oral and General Health-Related Quality of Life Among Young PDFDocumento6 páginas2009 - Oral and General Health-Related Quality of Life Among Young PDFfarrasoyaAinda não há avaliações

- 2009 - Oral and General Health-Related Quality of Life Among YoungDocumento6 páginas2009 - Oral and General Health-Related Quality of Life Among YoungfarrasoyaAinda não há avaliações

- Jaber 2011Documento6 páginasJaber 2011Alvaro LaraAinda não há avaliações

- Impact of Orthodontic Treatment On Oral Health-Related Quality of Life in The Slovak Republic: A Cross-Sectional StudyDocumento10 páginasImpact of Orthodontic Treatment On Oral Health-Related Quality of Life in The Slovak Republic: A Cross-Sectional StudyKornist BufuAinda não há avaliações

- Original Article Oral Dryness Among Japanese Youth: Development of A Japanese Questionnaire On Oral Dryness and The Impact of Daily Life On ItDocumento6 páginasOriginal Article Oral Dryness Among Japanese Youth: Development of A Japanese Questionnaire On Oral Dryness and The Impact of Daily Life On ItDanis Diba Sabatillah YaminAinda não há avaliações

- Knowledge, Attitudes, Practices and Status of Oral Health Among Diabetic Patients at Kikuyu HospitalDocumento2 páginasKnowledge, Attitudes, Practices and Status of Oral Health Among Diabetic Patients at Kikuyu HospitalNthie UnguAinda não há avaliações

- School Performance 4Documento9 páginasSchool Performance 4Putik Benang Sari FloristAinda não há avaliações

- Thesis On Oral Health Related Quality of LifeDocumento5 páginasThesis On Oral Health Related Quality of Lifeafknawjof100% (2)

- The Relationship Between ChildrenDocumento14 páginasThe Relationship Between ChildrentirahamdillahAinda não há avaliações

- The Relationship Between Periodontal Disease and Public Health: A Population-Based StudyDocumento6 páginasThe Relationship Between Periodontal Disease and Public Health: A Population-Based StudyHtet AungAinda não há avaliações

- Articulo Variables 1Documento10 páginasArticulo Variables 1Diego LemurAinda não há avaliações

- 0718 381X Ijodontos 14 02 183Documento8 páginas0718 381X Ijodontos 14 02 183AlyaAinda não há avaliações

- Clinical Pediatrics: Parental Perspectives of Early Childhood CariesDocumento10 páginasClinical Pediatrics: Parental Perspectives of Early Childhood CariesBasant ShamsAinda não há avaliações

- Fel Cio 2017Documento12 páginasFel Cio 2017Edsh Radgedolf RosalesAinda não há avaliações

- Pengetahuan Dan Perilaku Kesehatan Gigi Pada Siswa SDN 174 Muara Fajar PekanbaruDocumento5 páginasPengetahuan Dan Perilaku Kesehatan Gigi Pada Siswa SDN 174 Muara Fajar PekanbaruTeddy Kurniady ThaherAinda não há avaliações

- Lollipop UCLA NursingStudyDocumento5 páginasLollipop UCLA NursingStudySam DyerAinda não há avaliações

- 198 842 2 PBDocumento12 páginas198 842 2 PBYusuf DiansyahAinda não há avaliações

- 2-Khanh Et Al. - 2015 - Early Childhood Caries, Mouth Pain, and NutritionaDocumento8 páginas2-Khanh Et Al. - 2015 - Early Childhood Caries, Mouth Pain, and Nutritionatitah rahayuAinda não há avaliações

- JADA 2011 Dye 173 83Documento12 páginasJADA 2011 Dye 173 83Risal RisamsahAinda não há avaliações

- JCDR 8 134 ZD07 PDFDocumento4 páginasJCDR 8 134 ZD07 PDFTaufiqurrahman Abdul DjabbarAinda não há avaliações

- A New System For Classifying Root and Root Canal Morphology: ReviewDocumento11 páginasA New System For Classifying Root and Root Canal Morphology: Reviewshamshuddin patelAinda não há avaliações

- Reviews: Oral and Maxillofacial Trauma, 4Th EditionDocumento1 páginaReviews: Oral and Maxillofacial Trauma, 4Th EditionTaufiqurrahman Abdul DjabbarAinda não há avaliações

- Dental Patient 0510 PDFDocumento1 páginaDental Patient 0510 PDFTaufiqurrahman Abdul DjabbarAinda não há avaliações

- Living Oracles of The Law and The Fallacy of Human Divination PDFDocumento14 páginasLiving Oracles of The Law and The Fallacy of Human Divination PDFTaufiqurrahman Abdul DjabbarAinda não há avaliações

- Caac172 PDFDocumento4 páginasCaac172 PDFTaufiqurrahman Abdul DjabbarAinda não há avaliações

- Obm 2004 04 s0283Documento7 páginasObm 2004 04 s0283Taufiqurrahman Abdul DjabbarAinda não há avaliações

- 49342Documento2 páginas49342Taufiqurrahman Abdul DjabbarAinda não há avaliações

- Management of C Shaped Canals: 3 Case ReportsDocumento3 páginasManagement of C Shaped Canals: 3 Case ReportsTaufiqurrahman Abdul Djabbar100% (1)

- GOHAIDocumento8 páginasGOHAITaufiqurrahman Abdul DjabbarAinda não há avaliações

- Social and Clinical Factors Associated With OralDocumento6 páginasSocial and Clinical Factors Associated With OralTaufiqurrahman Abdul DjabbarAinda não há avaliações

- OMS Resident ManualDocumento84 páginasOMS Resident ManualTaufiqurrahman Abdul DjabbarAinda não há avaliações

- Rgo 2010 2230Documento10 páginasRgo 2010 2230Taufiqurrahman Abdul DjabbarAinda não há avaliações

- Jurnal 4Documento26 páginasJurnal 4ferryAinda não há avaliações

- RM 15015Documento6 páginasRM 15015Taufiqurrahman Abdul DjabbarAinda não há avaliações

- 2012 Fabiola JAGSDocumento6 páginas2012 Fabiola JAGSTaufiqurrahman Abdul DjabbarAinda não há avaliações

- Vol09 2 3-5str PDFDocumento3 páginasVol09 2 3-5str PDFTaufiqurrahman Abdul DjabbarAinda não há avaliações

- V1 10 3 PDFDocumento5 páginasV1 10 3 PDFTaufiqurrahman Abdul DjabbarAinda não há avaliações

- Translation and Validation of The Arabic Version of The Geriatric Oral Health Assessment Index (GOHAI)Documento7 páginasTranslation and Validation of The Arabic Version of The Geriatric Oral Health Assessment Index (GOHAI)Taufiqurrahman Abdul DjabbarAinda não há avaliações

- Final Article Drugs and AgingDocumento11 páginasFinal Article Drugs and AgingTaufiqurrahman Abdul DjabbarAinda não há avaliações

- Residency BrochureDocumento12 páginasResidency BrochureTaufiqurrahman Abdul DjabbarAinda não há avaliações

- 17301Documento4 páginas17301Taufiqurrahman Abdul DjabbarAinda não há avaliações

- 0042 84501400077PDocumento8 páginas0042 84501400077PTaufiqurrahman Abdul DjabbarAinda não há avaliações

- Dentistry Residency Oral SurgeryDocumento3 páginasDentistry Residency Oral SurgeryTaufiqurrahman Abdul DjabbarAinda não há avaliações

- OmsDocumento41 páginasOmsTaufiqurrahman Abdul DjabbarAinda não há avaliações

- Open Positions ExternshipDocumento22 páginasOpen Positions ExternshipTaufiqurrahman Abdul DjabbarAinda não há avaliações

- Dentin and Pulp Reactions To Caries and Operative Treatment - Biological Variables Affecting TreatDocumento14 páginasDentin and Pulp Reactions To Caries and Operative Treatment - Biological Variables Affecting TreatMaria UiuiuAinda não há avaliações

- Jcpe 12081Documento14 páginasJcpe 12081Taufiqurrahman Abdul DjabbarAinda não há avaliações

- Life Review PaperDocumento8 páginasLife Review Papercompmom5100% (1)

- Old Age HomeDocumento10 páginasOld Age HomeRajan TiwariAinda não há avaliações

- Areas of Social WorkDocumento6 páginasAreas of Social WorkCindy PalenAinda não há avaliações

- Sarah J. (Englert) Dunham RN, BSN, MS, FNPDocumento3 páginasSarah J. (Englert) Dunham RN, BSN, MS, FNPapi-309264509Ainda não há avaliações

- Chapter 1 - ThesisDocumento11 páginasChapter 1 - ThesisSaileneGuemoDellosaAinda não há avaliações

- Caldeira 2018Documento6 páginasCaldeira 2018Engels Yeltsin Ponce GonzalesAinda não há avaliações

- 308904-The QLD FreemaDocumento40 páginas308904-The QLD Freemaagenzia massonica internazionaleAinda não há avaliações

- Iyeokan Ativie's Cover Letter 2013Documento1 páginaIyeokan Ativie's Cover Letter 2013Ella McAtiveAinda não há avaliações

- Restraint Paper 3Documento9 páginasRestraint Paper 3api-404185844Ainda não há avaliações

- NEWS2 Chart 4 - Clinical Response To NEWS Trigger Thresholds - 0 PDFDocumento1 páginaNEWS2 Chart 4 - Clinical Response To NEWS Trigger Thresholds - 0 PDFArisita Andy PutriAinda não há avaliações

- Caregivers JumpDocumento2 páginasCaregivers JumpSaerom Yoo EnglandAinda não há avaliações

- HW Independent Living 2014 WebDocumento14 páginasHW Independent Living 2014 WebDuca RadoAinda não há avaliações

- CKHA Imagine 2Documento2 páginasCKHA Imagine 2krobinetAinda não há avaliações

- Telephonic RN Case ManagerDocumento2 páginasTelephonic RN Case Managerapi-78703590Ainda não há avaliações

- What Is The CDR?Documento9 páginasWhat Is The CDR?Rizki Annisa RahardhianyAinda não há avaliações

- Braden Scale Risk Assessment SheetDocumento2 páginasBraden Scale Risk Assessment SheetAmyAinda não há avaliações

- Haryana Hospital ListDocumento20 páginasHaryana Hospital Listashutosh kumarAinda não há avaliações

- Cummings - Alzheimer's Disease and Parkinson's Disease: Comparison of Speech and Language AlterationsDocumento6 páginasCummings - Alzheimer's Disease and Parkinson's Disease: Comparison of Speech and Language AlterationsCami Sánchez SalinasAinda não há avaliações

- Strategies Used by Occupational Therapy To Maximize ADL IndependenceDocumento53 páginasStrategies Used by Occupational Therapy To Maximize ADL IndependenceNizam lotfiAinda não há avaliações

- 2 Assessments SNOMED OT Subset Oct2016 0Documento8 páginas2 Assessments SNOMED OT Subset Oct2016 0Shibli Rahman100% (2)

- GERIA Unit 4 LearnersDocumento34 páginasGERIA Unit 4 Learners3D - AURELIO, Lyca Mae M.Ainda não há avaliações

- Adult Nursing Research ProjectDocumento9 páginasAdult Nursing Research ProjectTracy KAinda não há avaliações

- Caidas en Urgencias 2023Documento16 páginasCaidas en Urgencias 2023Daniel GonzálezAinda não há avaliações

- Chap 004 BDocumento72 páginasChap 004 BJessica ColaAinda não há avaliações

- Moca ReviewDocumento4 páginasMoca ReviewLuthfi IndiwirawanAinda não há avaliações

- ClozapineDocumento4 páginasClozapinePaulo de JesusAinda não há avaliações

- DAFTAR PUSTAKA Proposal WidiaDocumento4 páginasDAFTAR PUSTAKA Proposal WidiaPutri Alin Kende RiaralyAinda não há avaliações

- This Is Me: My Care PassportDocumento23 páginasThis Is Me: My Care PassportdwightAinda não há avaliações

- Frontal Assessment Battery SVUH MedEl ToolDocumento2 páginasFrontal Assessment Battery SVUH MedEl ToolclauytomasAinda não há avaliações

- BSI BibDocumento41 páginasBSI BibdrmssAinda não há avaliações