Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

United States v. Mitchell Diamond, 820 F.2d 10, 1st Cir. (1987)

Enviado por

Scribd Government DocsDireitos autorais

Formatos disponíveis

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

United States v. Mitchell Diamond, 820 F.2d 10, 1st Cir. (1987)

Enviado por

Scribd Government DocsDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

820 F.

2d 10

UNITED STATES of America, Appellant,

v.

Mitchell DIAMOND, Defendant, Appellee.

No. 86-1380.

United States Court of Appeals,

First Circuit.

Argued May 6, 1987.

Decided June 1, 1987.

Susan R. Via, Asst. U.S. Atty., with whom Frank L. McNamara, Jr., U.S.

Atty., Boston, Mass., was on supplemental brief, for appellant.

David Berman with whom Berman and Moren, Lynn, Mass., was on

supplemental brief for defendant, appellee.

Before CAMPBELL, Chief Judge, and COFFIN, BOWNES, BREYER,

TORRUELLA and SELYA, Circuit Judges.

COFFIN, Circuit Judge.

This case comes to us on an appeal by the government from a ruling by the

district court granting defendant's pretrial motion to suppress thirteen

videotapes, other materials, and statements obtained in a search of his

residence. The challenged portion of the search warrant authorized the seizure

of videotapes "depicting prepubescent children or children under the age of 18

years involved in sexually explicit conduct." The court concluded that the

warrant failed to "meet the standard of specificity required when a warrant

authorizes seizure of materials which may be protected by the First

Amendment," because it impermissibly vested the searching officers with

discretion to determine whether the videotapes depicted children under the age

of 18. The district court relied especially upon our decision in United States v.

Guarino, 729 F.2d 864 (1st Cir.1984), wherein we held that the particularly

requirement of the Fourth Amendment1 was violated by a warrant permitting

police to seize "obscene materials of the same tenor as" three named

magazines.

A panel of this court affirmed the suppression of the videotapes in a divided

opinion, which was subsequently withdrawn when this case was ordered to be

considered by the entire court en banc. We now deem the record in this case

insufficiently developed to require us to address the particularity issue and

remand for further evaluation of the videotapes.

The affidavit presented to the magistrate identified six videotapes which

defendant had mailed to government undercover agents. Virtually all of these

films were described as depicting "Lolitas" a term the affiant said he knew was

"commonly used by pornography collectors and pedophiles to describe

prepubescent girls engaged in sexual activity." (Appendix at 9, para. 10.) Two,

received by a postal inspector on July 19, 1984, consisted of a "package," one

"Lolita" and a "teen tape" (Appendix at 12); two others received the same day

were labeled "Lol & Barnyard." The remaining two, received on August 10,

1984, consisted of "the better Lolitas" plus "teens and a few barnyard

[bestiality] films." (Appendix at 18.) Throughout the 45 paragraph affidavit

defendant is quoted as being interested in acquiring "Lolitas," which he

distinguishes repeatedly from "teenage" tapes and films.

After reviewing this affidavit and the six videotapes, the magistrate issued a

warrant on December 10, 1984, the relevant section of which (Paragraph C.1)

authorized the seizure of

All video tapes and/or 8 millimeter loops or other visual media depicting

prepubescent children or children under the age of 18 years involved in sexually

explicit conduct--i.e., sexual intercourse, including genital-to-genital, oralgenital, anal-genital, between persons of the same and/or opposite sex; and/or

masturbation.

Other portions of the warrant authorized the seizure of equipment used to

produce the videotapes referred to in paragraph C.1. and of records and

documents related to those videotapes.

Subsequently, on December 11, 1984, ten to fifteen police officers, postal

inspectors, and a United States Customs Agent executed the search of

defendant's home. (Suppression Hearing at 22.) Portions of the search were

recorded on a two-hour videotape. Defendant possessed some 800 videotapes,

and it is clear from the record of the suppression hearing that the defendant

identified for the searching officers videotapes he thought met the warrant's

description. (Suppression Hearing at 31-33.) The videotape shows defendant

taking tapes down from the shelves and stacking them. (Suppression Hearing at

52.) The defendant's answers to questions at the Suppression Hearing indicated

that he referred to these tapes interchangeably as "child pornography

videotapes" (Suppression Hearing at 33) and as "Lolitas" (Suppression Hearing

at 35). All fifteen of the videotapes seized were located in about an hour. The

officers then proceeded to view the videotapes and to execute other portions of

the search warrant. The entire search took a little over seven hours. (Appendix

at 154-57.)

8

After the search, defendant filed a motion to suppress "all VHS, Beta or other

videotapes," along with all books, papers, video recording or playing

equipment, and statements obtained during the search. Briefing and oral

argument proceeded on an all-or-nothing basis. The court, therefore, did not

examine the thirteen tapes that it suppressed.2

The question whether a warrant authorizing seizures of films depicting sexual

activity by children under 18 violates the particularity requirement of the

Fourth Amendment is a significant one of current interest. United States v.

Wiegand, 812 F.2d 1239 (9th Cir.1987) (upholding warrant authorizing seizure

of videotapes "depicting a person under the age of 18 years"). Before pushing

to the frontiers of constitutional analysis, however, we think it sound policy to

see if a more modest basis for resolving the suppression motion exists. See

Alabama State Federation of Labor v. McAdory, 325 U.S. 450, 461, 65 S.Ct.

1384, 1389-90, 89 L.Ed. 1725 (1945) (explaining the Court's policy not "to

decide any constitutional question in advance of the necessity for its decision,

... or to formulate a rule of constitutional law broader than is required by the

precise facts to which it is to be applied"). See also Rescue Army v. Municipal

Court, 331 U.S. 549, 568-72, 67 S.Ct. 1409, 1419-21, 91 L.Ed. 1666 (1947);

Ashwander v. Tennessee Valley Authority, 297 U.S. 288, 346, 56 S.Ct. 466,

482, 80 L.Ed. 688 (1936) (Brandeis, J., concurring). We, therefore, resist a rush

to judgment.

10

Both in its supplemental brief in support of rehearing en banc and at oral

argument, the government informed this court that each of the thirteen

videotapes suppressed by the district court contains at least one scene involving

prepubescent children. If this fact were established by the record, we think it

clear that there could be no successful motion to suppress based on improper

discretion allowed a seizing officer. The warrant's description of films

involving "prepubescent children" provides a relatively objective standard for

police officers to follow. Though there might be certain exceptional cases in

which mistakes might be made about the signs of puberty in a particular

individual, any tapes mistakenly seized under the description "prepubescent

children" would most certainly be of individuals under the age of 18: any such

tapes would, therefore, be of evidentiary value in a criminal prosecution under

the Child Protection Act, 18 U.S.C. Sec. 2252(a). Since the warrant's

description of films depicting "prepubescent children" was constitutionally

sufficient, such films could be properly seized and admitted into evidence

whether or not the additional phrase "children under the age of 18" was

particular enough. United States v. Riggs, 690 F.2d 298 (1st Cir.1982) (film

seized pursuant to valid portion of search warrant was admissible even if other

portions of the warrant were invalid).

11

From our reading of the affidavit and the transcript of the suppression hearing,

we think it a substantial possibility that many, if not all, of the seized

videotapes included scenes involving prepubescent children. Even if some of

the tapes prove to be of apparently pubescent or late teenage young people, and

were to be suppressed by the district court, we would assume that the

government would seek an appeal only if such tapes were deemed critical to the

prosecution. In short, it is possible that there will be no need to face the close

question concerning the "children under the age of 18" language.

12

We, therefore, direct the district court to review the videotapes to see how

many are admissible as depicting prepubescent children engaging in the

described sexually explicit conduct. If an issue remains concerning videotapes

which do not depict prepubescent children in such activity, the court, of course,

will address that issue. We add that the court should also specifically address

those portions of the warrant authorizing the seizure of video equipment and

other materials to see if they were drafted with particularity and supported by

probable cause.

13

The judgment is vacated and the case is remanded for further proceedings

consistent with this opinion.

"... no Warrants shall issue, but ... particularly describing the ... things to be

seized."

The government returned two of the videotapes which it alleged depicted adult

bestiality. (Appendix at 170.)

Você também pode gostar

- United States v. Ray Donald Loy, 191 F.3d 360, 3rd Cir. (1999)Documento14 páginasUnited States v. Ray Donald Loy, 191 F.3d 360, 3rd Cir. (1999)Scribd Government DocsAinda não há avaliações

- United States v. Karriem Al-Amin Shabazz, 724 F.2d 1536, 11th Cir. (1984)Documento6 páginasUnited States v. Karriem Al-Amin Shabazz, 724 F.2d 1536, 11th Cir. (1984)Scribd Government DocsAinda não há avaliações

- United States v. Frabizio, 459 F.3d 80, 1st Cir. (2006)Documento23 páginasUnited States v. Frabizio, 459 F.3d 80, 1st Cir. (2006)Scribd Government DocsAinda não há avaliações

- United States v. Burke, 10th Cir. (2011)Documento26 páginasUnited States v. Burke, 10th Cir. (2011)Scribd Government DocsAinda não há avaliações

- United States v. Burke, 633 F.3d 984, 10th Cir. (2011)Documento26 páginasUnited States v. Burke, 633 F.3d 984, 10th Cir. (2011)Scribd Government DocsAinda não há avaliações

- United States v. Michael Rodriguez, Michael Rodriguez, JR., William Donlan, Anthony Vessichio, and Fernando Diosa, 786 F.2d 472, 2d Cir. (1986)Documento10 páginasUnited States v. Michael Rodriguez, Michael Rodriguez, JR., William Donlan, Anthony Vessichio, and Fernando Diosa, 786 F.2d 472, 2d Cir. (1986)Scribd Government DocsAinda não há avaliações

- Huddleston v. United States, 485 U.S. 681 (1988)Documento10 páginasHuddleston v. United States, 485 U.S. 681 (1988)Scribd Government DocsAinda não há avaliações

- United States v. Juan Carols Arroyo-Reyes, 32 F.3d 561, 1st Cir. (1994)Documento6 páginasUnited States v. Juan Carols Arroyo-Reyes, 32 F.3d 561, 1st Cir. (1994)Scribd Government DocsAinda não há avaliações

- United States v. Luis Carbone, A/K/A "Luiggi,", 798 F.2d 21, 1st Cir. (1986)Documento10 páginasUnited States v. Luis Carbone, A/K/A "Luiggi,", 798 F.2d 21, 1st Cir. (1986)Scribd Government DocsAinda não há avaliações

- United States v. Hopkins, 47 F.3d 1156, 1st Cir. (1995)Documento6 páginasUnited States v. Hopkins, 47 F.3d 1156, 1st Cir. (1995)Scribd Government DocsAinda não há avaliações

- United States v. John Fabiano, 169 F.3d 1299, 10th Cir. (1999)Documento11 páginasUnited States v. John Fabiano, 169 F.3d 1299, 10th Cir. (1999)Scribd Government DocsAinda não há avaliações

- United States v. Alan Riggs, 690 F.2d 298, 1st Cir. (1982)Documento6 páginasUnited States v. Alan Riggs, 690 F.2d 298, 1st Cir. (1982)Scribd Government DocsAinda não há avaliações

- United States v. Alberto Ortiz-Rengifo, 832 F.2d 722, 2d Cir. (1987)Documento7 páginasUnited States v. Alberto Ortiz-Rengifo, 832 F.2d 722, 2d Cir. (1987)Scribd Government DocsAinda não há avaliações

- United States v. Khounsavanh, 113 F.3d 279, 1st Cir. (1997)Documento13 páginasUnited States v. Khounsavanh, 113 F.3d 279, 1st Cir. (1997)Scribd Government DocsAinda não há avaliações

- United States v. Tony Rucker, Robert Rucker, JR., 915 F.2d 1511, 11th Cir. (1990)Documento5 páginasUnited States v. Tony Rucker, Robert Rucker, JR., 915 F.2d 1511, 11th Cir. (1990)Scribd Government DocsAinda não há avaliações

- United States v. Soto-Cervantes, 10th Cir. (1998)Documento12 páginasUnited States v. Soto-Cervantes, 10th Cir. (1998)Scribd Government DocsAinda não há avaliações

- United States v. Julio Larracuente, 952 F.2d 672, 2d Cir. (1992)Documento4 páginasUnited States v. Julio Larracuente, 952 F.2d 672, 2d Cir. (1992)Scribd Government DocsAinda não há avaliações

- Filed: Patrick FisherDocumento10 páginasFiled: Patrick FisherScribd Government DocsAinda não há avaliações

- United States v. Femia, 9 F.3d 990, 1st Cir. (1993)Documento9 páginasUnited States v. Femia, 9 F.3d 990, 1st Cir. (1993)Scribd Government DocsAinda não há avaliações

- United States v. Vazquez-Guadalupe, 407 F.3d 492, 1st Cir. (2005)Documento11 páginasUnited States v. Vazquez-Guadalupe, 407 F.3d 492, 1st Cir. (2005)Scribd Government DocsAinda não há avaliações

- Filed: Patrick FisherDocumento12 páginasFiled: Patrick FisherScribd Government DocsAinda não há avaliações

- United States v. One Reel of Film. Gerard Damiano Productions, Inc., Claimant-Appellant, 481 F.2d 206, 1st Cir. (1973)Documento6 páginasUnited States v. One Reel of Film. Gerard Damiano Productions, Inc., Claimant-Appellant, 481 F.2d 206, 1st Cir. (1973)Scribd Government DocsAinda não há avaliações

- United States v. Eligio Palmer-Contreras and Jose A. Casanova Ortiz, 835 F.2d 15, 1st Cir. (1988)Documento6 páginasUnited States v. Eligio Palmer-Contreras and Jose A. Casanova Ortiz, 835 F.2d 15, 1st Cir. (1988)Scribd Government DocsAinda não há avaliações

- United States Court of Appeals, For The Fourth CircuitDocumento14 páginasUnited States Court of Appeals, For The Fourth CircuitScribd Government DocsAinda não há avaliações

- Janae Kingston, D/B/A Movie Buffs v. Utah County Carlyle K. Bryson, Utah County Attorney and David Bateman, Utah County Sheriff, 161 F.3d 17, 10th Cir. (1998)Documento8 páginasJanae Kingston, D/B/A Movie Buffs v. Utah County Carlyle K. Bryson, Utah County Attorney and David Bateman, Utah County Sheriff, 161 F.3d 17, 10th Cir. (1998)Scribd Government DocsAinda não há avaliações

- United States v. Clifton Thomas, 838 F.2d 1210, 4th Cir. (1988)Documento4 páginasUnited States v. Clifton Thomas, 838 F.2d 1210, 4th Cir. (1988)Scribd Government DocsAinda não há avaliações

- United States v. Angel Petit, Roger Fernandez, Francisco Pasqual, 841 F.2d 1546, 11th Cir. (1988)Documento17 páginasUnited States v. Angel Petit, Roger Fernandez, Francisco Pasqual, 841 F.2d 1546, 11th Cir. (1988)Scribd Government DocsAinda não há avaliações

- Astro Cinema Corp. Inc., John Justin and Jess Rockman v. Thomas J. MacKell District Attorney of Queens County, 422 F.2d 293, 2d Cir. (1970)Documento7 páginasAstro Cinema Corp. Inc., John Justin and Jess Rockman v. Thomas J. MacKell District Attorney of Queens County, 422 F.2d 293, 2d Cir. (1970)Scribd Government DocsAinda não há avaliações

- United States v. Djelilate, 4th Cir. (1999)Documento6 páginasUnited States v. Djelilate, 4th Cir. (1999)Scribd Government DocsAinda não há avaliações

- The United States v. Dean K. Felton, Nancy E. Bruce, John Zorak A/K/A Johnny, Anthony Serrao A/K/A Buddy, Richard Cox A/K/A Ricky, James Thurman, John Hathorne. Appeal of United States of America, 753 F.2d 256, 3rd Cir. (1985)Documento8 páginasThe United States v. Dean K. Felton, Nancy E. Bruce, John Zorak A/K/A Johnny, Anthony Serrao A/K/A Buddy, Richard Cox A/K/A Ricky, James Thurman, John Hathorne. Appeal of United States of America, 753 F.2d 256, 3rd Cir. (1985)Scribd Government DocsAinda não há avaliações

- UNITED STATES, Appellee, v. Noel FEMIA, Defendant, AppellantDocumento11 páginasUNITED STATES, Appellee, v. Noel FEMIA, Defendant, AppellantScribd Government DocsAinda não há avaliações

- United States v. Robert M. Friedland, 444 F.2d 710, 1st Cir. (1971)Documento4 páginasUnited States v. Robert M. Friedland, 444 F.2d 710, 1st Cir. (1971)Scribd Government DocsAinda não há avaliações

- United States v. Vincent Rizzo, 491 F.2d 215, 2d Cir. (1974)Documento5 páginasUnited States v. Vincent Rizzo, 491 F.2d 215, 2d Cir. (1974)Scribd Government DocsAinda não há avaliações

- United States Court of Appeals: For The First CircuitDocumento34 páginasUnited States Court of Appeals: For The First CircuitScribd Government DocsAinda não há avaliações

- United States v. Spencer, 10th Cir. (2005)Documento8 páginasUnited States v. Spencer, 10th Cir. (2005)Scribd Government DocsAinda não há avaliações

- United States v. Espino, 10th Cir. (2006)Documento10 páginasUnited States v. Espino, 10th Cir. (2006)Scribd Government DocsAinda não há avaliações

- United States v. Juan G. Rios, 611 F.2d 1335, 10th Cir. (1979)Documento21 páginasUnited States v. Juan G. Rios, 611 F.2d 1335, 10th Cir. (1979)Scribd Government DocsAinda não há avaliações

- United States Court of Appeals, Third CircuitDocumento22 páginasUnited States Court of Appeals, Third CircuitScribd Government DocsAinda não há avaliações

- United States v. Brunette, 256 F.3d 14, 1st Cir. (2001)Documento8 páginasUnited States v. Brunette, 256 F.3d 14, 1st Cir. (2001)Scribd Government DocsAinda não há avaliações

- United States v. Rodriguez-Pacheco, 475 F.3d 434, 1st Cir. (2007)Documento42 páginasUnited States v. Rodriguez-Pacheco, 475 F.3d 434, 1st Cir. (2007)Scribd Government DocsAinda não há avaliações

- United States v. Guadalupe Soto-Cervantes, 138 F.3d 1319, 10th Cir. (1998)Documento7 páginasUnited States v. Guadalupe Soto-Cervantes, 138 F.3d 1319, 10th Cir. (1998)Scribd Government DocsAinda não há avaliações

- United States v. Joseph John Valentich, A/K/A "Joe Valley", 737 F.2d 880, 10th Cir. (1984)Documento4 páginasUnited States v. Joseph John Valentich, A/K/A "Joe Valley", 737 F.2d 880, 10th Cir. (1984)Scribd Government DocsAinda não há avaliações

- United States v. Dennis Pennett, 496 F.2d 293, 10th Cir. (1974)Documento8 páginasUnited States v. Dennis Pennett, 496 F.2d 293, 10th Cir. (1974)Scribd Government DocsAinda não há avaliações

- United States v. 6 Fox Street, 480 F.3d 38, 1st Cir. (2007)Documento12 páginasUnited States v. 6 Fox Street, 480 F.3d 38, 1st Cir. (2007)Scribd Government DocsAinda não há avaliações

- United States v. Hilton, 386 F.3d 13, 1st Cir. (2004)Documento16 páginasUnited States v. Hilton, 386 F.3d 13, 1st Cir. (2004)Scribd Government DocsAinda não há avaliações

- United States v. Michael Peter Evanchik, Howard John Critzman, Carl Pugliese, and Thomas Sobeck, 413 F.2d 950, 2d Cir. (1969)Documento6 páginasUnited States v. Michael Peter Evanchik, Howard John Critzman, Carl Pugliese, and Thomas Sobeck, 413 F.2d 950, 2d Cir. (1969)Scribd Government DocsAinda não há avaliações

- United States v. Hilton, 386 F.3d 13, 1st Cir. (2004)Documento9 páginasUnited States v. Hilton, 386 F.3d 13, 1st Cir. (2004)Scribd Government DocsAinda não há avaliações

- United States v. Cattle King Packing Co., Inc., Rudolph G. "Butch" Stanko, and Gary Waderich, 793 F.2d 232, 10th Cir. (1986)Documento18 páginasUnited States v. Cattle King Packing Co., Inc., Rudolph G. "Butch" Stanko, and Gary Waderich, 793 F.2d 232, 10th Cir. (1986)Scribd Government DocsAinda não há avaliações

- Filed: Patrick FisherDocumento6 páginasFiled: Patrick FisherScribd Government DocsAinda não há avaliações

- United States Court of Appeals, Third CircuitDocumento12 páginasUnited States Court of Appeals, Third CircuitScribd Government DocsAinda não há avaliações

- United States v. Robinson, 144 F.3d 104, 1st Cir. (1998)Documento9 páginasUnited States v. Robinson, 144 F.3d 104, 1st Cir. (1998)Scribd Government DocsAinda não há avaliações

- United States v. Laine, 270 F.3d 71, 1st Cir. (2001)Documento6 páginasUnited States v. Laine, 270 F.3d 71, 1st Cir. (2001)Scribd Government DocsAinda não há avaliações

- United States v. Espinoza, 10th Cir. (2010)Documento9 páginasUnited States v. Espinoza, 10th Cir. (2010)Scribd Government DocsAinda não há avaliações

- United States v. John Paul Jones, 730 F.2d 593, 10th Cir. (1984)Documento6 páginasUnited States v. John Paul Jones, 730 F.2d 593, 10th Cir. (1984)Scribd Government DocsAinda não há avaliações

- United States v. Richard Mark Clinger and Charles Edward Harmon, 681 F.2d 221, 4th Cir. (1982)Documento5 páginasUnited States v. Richard Mark Clinger and Charles Edward Harmon, 681 F.2d 221, 4th Cir. (1982)Scribd Government DocsAinda não há avaliações

- United States v. Dalton Green, 887 F.2d 25, 1st Cir. (1989)Documento5 páginasUnited States v. Dalton Green, 887 F.2d 25, 1st Cir. (1989)Scribd Government DocsAinda não há avaliações

- United States v. Jesus Ortiz, 553 F.2d 782, 2d Cir. (1977)Documento11 páginasUnited States v. Jesus Ortiz, 553 F.2d 782, 2d Cir. (1977)Scribd Government DocsAinda não há avaliações

- United States v. Richard Torch, 609 F.2d 1088, 4th Cir. (1979)Documento7 páginasUnited States v. Richard Torch, 609 F.2d 1088, 4th Cir. (1979)Scribd Government DocsAinda não há avaliações

- United States v. Andrew M. Harvey, III, 2 F.3d 1318, 3rd Cir. (1993)Documento18 páginasUnited States v. Andrew M. Harvey, III, 2 F.3d 1318, 3rd Cir. (1993)Scribd Government DocsAinda não há avaliações

- Payn v. Kelley, 10th Cir. (2017)Documento8 páginasPayn v. Kelley, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government Docs50% (2)

- United States v. Kieffer, 10th Cir. (2017)Documento20 páginasUnited States v. Kieffer, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsAinda não há avaliações

- United States v. Olden, 10th Cir. (2017)Documento4 páginasUnited States v. Olden, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsAinda não há avaliações

- United States v. Garcia-Damian, 10th Cir. (2017)Documento9 páginasUnited States v. Garcia-Damian, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government Docs100% (1)

- City of Albuquerque v. Soto Enterprises, 10th Cir. (2017)Documento21 páginasCity of Albuquerque v. Soto Enterprises, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsAinda não há avaliações

- Apodaca v. Raemisch, 10th Cir. (2017)Documento15 páginasApodaca v. Raemisch, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsAinda não há avaliações

- Consolidation Coal Company v. OWCP, 10th Cir. (2017)Documento22 páginasConsolidation Coal Company v. OWCP, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsAinda não há avaliações

- Greene v. Tennessee Board, 10th Cir. (2017)Documento2 páginasGreene v. Tennessee Board, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsAinda não há avaliações

- Pecha v. Lake, 10th Cir. (2017)Documento25 páginasPecha v. Lake, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsAinda não há avaliações

- Coyle v. Jackson, 10th Cir. (2017)Documento7 páginasCoyle v. Jackson, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government Docs100% (1)

- Wilson v. Dowling, 10th Cir. (2017)Documento5 páginasWilson v. Dowling, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsAinda não há avaliações

- Brown v. Shoe, 10th Cir. (2017)Documento6 páginasBrown v. Shoe, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsAinda não há avaliações

- Harte v. Board Comm'rs Cnty of Johnson, 10th Cir. (2017)Documento100 páginasHarte v. Board Comm'rs Cnty of Johnson, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsAinda não há avaliações

- Publish United States Court of Appeals For The Tenth CircuitDocumento14 páginasPublish United States Court of Appeals For The Tenth CircuitScribd Government Docs100% (1)

- United States v. Roberson, 10th Cir. (2017)Documento50 páginasUnited States v. Roberson, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsAinda não há avaliações

- Publish United States Court of Appeals For The Tenth CircuitDocumento24 páginasPublish United States Court of Appeals For The Tenth CircuitScribd Government DocsAinda não há avaliações

- United States v. Magnan, 10th Cir. (2017)Documento27 páginasUnited States v. Magnan, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsAinda não há avaliações

- Publish United States Court of Appeals For The Tenth CircuitDocumento10 páginasPublish United States Court of Appeals For The Tenth CircuitScribd Government DocsAinda não há avaliações

- United States v. Windom, 10th Cir. (2017)Documento25 páginasUnited States v. Windom, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsAinda não há avaliações

- Webb v. Allbaugh, 10th Cir. (2017)Documento18 páginasWebb v. Allbaugh, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsAinda não há avaliações

- United States v. Voog, 10th Cir. (2017)Documento5 páginasUnited States v. Voog, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsAinda não há avaliações

- United States v. Henderson, 10th Cir. (2017)Documento2 páginasUnited States v. Henderson, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsAinda não há avaliações

- Publish United States Court of Appeals For The Tenth CircuitDocumento17 páginasPublish United States Court of Appeals For The Tenth CircuitScribd Government DocsAinda não há avaliações

- United States v. Kearn, 10th Cir. (2017)Documento25 páginasUnited States v. Kearn, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsAinda não há avaliações

- Northglenn Gunther Toody's v. HQ8-10410-10450, 10th Cir. (2017)Documento10 páginasNorthglenn Gunther Toody's v. HQ8-10410-10450, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsAinda não há avaliações

- NM Off-Hwy Vehicle Alliance v. U.S. Forest Service, 10th Cir. (2017)Documento9 páginasNM Off-Hwy Vehicle Alliance v. U.S. Forest Service, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsAinda não há avaliações

- United States v. Muhtorov, 10th Cir. (2017)Documento15 páginasUnited States v. Muhtorov, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsAinda não há avaliações

- United States v. Kundo, 10th Cir. (2017)Documento7 páginasUnited States v. Kundo, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsAinda não há avaliações

- Pledger v. Russell, 10th Cir. (2017)Documento5 páginasPledger v. Russell, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsAinda não há avaliações

- United States v. Magnan, 10th Cir. (2017)Documento4 páginasUnited States v. Magnan, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsAinda não há avaliações

- 397 L&O V 2023 Order Issued On Accelerated Promotions 0001Documento2 páginas397 L&O V 2023 Order Issued On Accelerated Promotions 0001md bashaAinda não há avaliações

- A Profile of Etta ConnorDocumento5 páginasA Profile of Etta ConnorToby P. NewsteadAinda não há avaliações

- MOU Campus Ambassador JYC20Documento5 páginasMOU Campus Ambassador JYC20Harshit UpadhyayAinda não há avaliações

- MOUs PDFDocumento73 páginasMOUs PDFRecordTrac - City of OaklandAinda não há avaliações

- Atf F 5400 13Documento7 páginasAtf F 5400 13AunvreAinda não há avaliações

- 1000 Lea Board QuestionsDocumento148 páginas1000 Lea Board QuestionsMakAinda não há avaliações

- Recruitment and PlacementDocumento9 páginasRecruitment and PlacementEthel Joi Manalac MendozaAinda não há avaliações

- PP Vs Sosing (Conspiracy)Documento13 páginasPP Vs Sosing (Conspiracy)nikkibeverly73Ainda não há avaliações

- 9.1 Censure Suspension or ExpulsionDocumento2 páginas9.1 Censure Suspension or ExpulsionAnonymous UZpqFni2WAinda não há avaliações

- Section 45 of The Air Force Act, 1950": Submitted byDocumento23 páginasSection 45 of The Air Force Act, 1950": Submitted byyash tyagiAinda não há avaliações

- Panganiban Vs PeopleDocumento3 páginasPanganiban Vs PeopleRose Mary G. Enano100% (1)

- Burciaga, Andres-Statement of Probable CauseDocumento2 páginasBurciaga, Andres-Statement of Probable CauseAnonymous AWI0cmAinda não há avaliações

- 07 20 11 SamplejobanalysisreDocumento66 páginas07 20 11 SamplejobanalysisreUsama Bin AlamAinda não há avaliações

- EU-US Data Protection Negotiations FactsheetDocumento3 páginasEU-US Data Protection Negotiations FactsheetvampiriAinda não há avaliações

- Services - Ref:: AdministrationDocumento3 páginasServices - Ref:: AdministrationGptc Chekkanurani100% (1)

- Hercor College Criminal Justice QuestionnaireDocumento3 páginasHercor College Criminal Justice QuestionnaireCatherine Joy CataminAinda não há avaliações

- Laundry OrientationDocumento1 páginaLaundry OrientationAlex GamegroupAinda não há avaliações

- Notice of Rescinsion of LicenseDocumento3 páginasNotice of Rescinsion of LicenseCkaStu100% (7)

- Shibu Soren Trial Court Judgement-Jha Murder CaseDocumento215 páginasShibu Soren Trial Court Judgement-Jha Murder CaseSampath BulusuAinda não há avaliações

- PP V Rosauro DigestDocumento2 páginasPP V Rosauro DigestGian BermudoAinda não há avaliações

- Flyers For CDMDocumento2 páginasFlyers For CDMErrych RychAinda não há avaliações

- Violation of Human Rights by The Police in Kerala-A StudyDocumento31 páginasViolation of Human Rights by The Police in Kerala-A StudyAarav TripathiAinda não há avaliações

- People vs. Delos ReyesDocumento48 páginasPeople vs. Delos ReyesIyaAinda não há avaliações

- SC upholds narrow reading of "transactionDocumento2 páginasSC upholds narrow reading of "transactionEarvin James AtienzaAinda não há avaliações

- Sally Beauty Supply Job ApplicationDocumento6 páginasSally Beauty Supply Job ApplicationCody BennettAinda não há avaliações

- Colorado Revised Statutes 2018Documento222 páginasColorado Revised Statutes 2018Michael_Lee_RobertsAinda não há avaliações

- Boc Guidelines Issuance and Lifting of Alert OrdersDocumento9 páginasBoc Guidelines Issuance and Lifting of Alert OrdersAriel Genaro JawidAinda não há avaliações

- Peoria County Booking Sheet 09/14/14Documento9 páginasPeoria County Booking Sheet 09/14/14Journal Star police documentsAinda não há avaliações

- People of The Philippines Vs ValencianoDocumento2 páginasPeople of The Philippines Vs ValencianoBruce EstilloteAinda não há avaliações

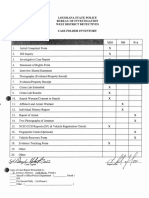

- Case Folder Inventory: Louisiana State Police Bureau of Investigation West District DetectivesDocumento60 páginasCase Folder Inventory: Louisiana State Police Bureau of Investigation West District DetectivesEthan Brown0% (1)