Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

(Go Igo Baduk Weiqi) (Eng) The Magic of Go - Richard Bozulich

Enviado por

Josh LuckerDescrição original:

Título original

Direitos autorais

Formatos disponíveis

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

(Go Igo Baduk Weiqi) (Eng) The Magic of Go - Richard Bozulich

Enviado por

Josh LuckerDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

The magic of Go

Richard Bozulich

By Richard Bozulich

The origins of go

The origins of go are concealed in unchronicled past of ancient China. There is a tangle of conflicting popular and scholarly anecdotes attributing its invention to two Chinese emperors, an imperial vassal, and court astrologers. One story has it that go was invented by the legendary Emperor Yao (ruled 2357-2256 B.C.) as an amusement for his idiot son. A second claims that the Emperor Shun (ruled 22552205 B.C.) created the game in hopes of improving his weak-minded son's mental prowess. A third says the person named Wu, a vassal of the Emperor Jie (ruled 1818-1766 B.C.), invented go as well as games of cards. Finally, a fourth theory suggests that go was developed by court astrologers during the Zhou dynasty (1045-255 B.C.). In any event, it is generally agreed that go is at least 3,000 and might be as much as 4,000 years old, which makes it the world's oldest strategic board game. Go probably evolved out of a method of divination practiced by the kings and shaman-astrologers of the early Zhou culture. One of these methods is believed to have entailed the casting of black and white pieces on a square board marked with astrological and geomantic symbols. Some fundamental go terms still in use today have astrological meanings. For example, the central point of the board is called tengen, "axis of heaven," and the eight specially marked points near the perimeter are called hoshi, "stars," the nine together making up the traditional "Nine Lights of Heaven," i.e., the seven stars of Ursa Major (the center of the Chinese astronomical system), the sun and the moon. The four quarters of the board are named after the four directions, each correlated to one of the basic trigrams of the "I-Ching" system. Beginning at the upper right and going clockwise, they are: Southwest (female, earth), Northwest (male, heaven), Northeast (hard, limit), and Southeast (gentle, yielding). The earliest mention of go appears in the "Analects" of Confucius, which was believed to have been written in the 5th century B.C., while the earliest physical evidence was a 17x17 line go board discovered in 1952 in a tomb of the former Han dynasty (206 B.C.- A.D. 9).

The magic of Go

Richard Bozulich

Go and the Immortals

The kanji character for "sage" or "immortal" is composed of two elements which signify "mountain person." The word was applied to someone who was not only wise but ageless, someone in possession of supernatural powers and able to wander through heaven and Earth at will. In China and Japan, mountains were regarded as realms of mystery. Uncanny things happened on mountaintops, and a person who spent years among the peaks, remote from everyday concerns, was believed to acquire a type of knowledge beyond the ken of ordinary folk. The progenitors of such awe-inspiring figures are to be found in the shamans and diviners of early China. Their activities were intimately bound up with the birth of Taoist philosophy and thus with the development of go itself. An interesting example of the gradual growth of supernatural ideas around the go board is given by Liu Tsung-yuen, writing in 815, when he described a mountain in southern China: "Below the shallows of the north-flowing Hsun water, and then west, is the socalled "Mountain of the Transcendents' Go Game." This mountain can be ascended from the west. There is a cavern at its top, and this cavern has screens, chambers and eaves. Under these eaves there are figures formed from flowing stone. After ascending to the topmost cavern, go out to the north and you will be looking down on a great wilderness and on flying birds--all you will discern of them is their backs. The first person to ascend here obtained a stone-and-board game on the summit, with red veins on a black surface, making eighteen pathways, suitable for go." There are many legends about people who by chance encounter an immortal. The old Chinese story, "Ranka," which made a deep impression on the Japanese mind, tells of a certain Wang Chih, a woodcutter: "Wang Chih was a hardy young fellow who used to venture deep into the mountains to find suitable wood for his ax. One day he went farther than usual and became lost. He wandered about for a while and eventually came upon two strange old men who were playing go, their board resting on a rock between them. Wang Chih was fascinated. He put down his ax and began to watch. One of the players gave him something like a date to chew on, so that he felt neither hunger nor thirst. As he continued to watch he fell into a trance for what seemed like an hour or two. When he awoke, however, the two old men were no longer there. He found that his ax handle had rotted to dust and he had grown a long beard. When he got back to his native village he discovered that his family had disappeared and that no one even remembered his name." In Japanese, the word "ranka" means "rotten ax handle," and it is often used as a poetic name for go.

The magic of Go

Richard Bozulich

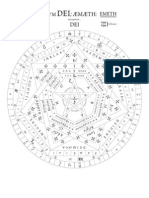

In 1715, the playwright Chikamatsu made use of this legend in a scene in his play "The Battles of Coxinga." Coxinga, called Go Sankei in Chikamatsu's play, notices two old men with shaggy eyebrows and white hair absorbed in a game of go, seemingly in perfect harmony with nature. Fascinated, Go Sankei muses, "Can this be the pure world of enlightenment?" Carried away with curiosity he cries out. "Old gentlemen, I am interested to see you playing go. Is there some special pleasure to be found in this contest?" One old man, without seeming to answer, speaks. "If it looks like a go board to you, it is a go board, and for the eye that sees go stones, they are merely go stones. But the go board is like the world. For those who see with their minds, the center of the universe is here. From the vantage point of this board, nothing will cloud our view of mountains, rivers, grasses, or trees of all China. The 90 intersections of each quarter of the board represent the 90 days of each of the four seasons. Together they come to 360. How foolish of you not to realize that we spend one day on each intersection!" "Extraordinary!" says Go Sankei. "But why should you two oppose each other as your sole pleasure?" "If there were not both yin and yang," the old man replies, "there would be no order in creation." Go Sankei: "And the result of your contest?" Old Man: "Does not the good and bad fortune of mankind depend on the chance of the moment?" Go Sankei: "And the black and the white?" Old Man: "The night and the day." Go Sankei: "What are the rules?" Old Man: "The stratagems of war."

Go comes to Japan

Go was probably brought to Japan from Korea by artists, scholars and former officials who migrated to Japan to escape political turmoil in their own land. There are no written records verifying the precise date of go's introduction into Japan, but according to the "Records of the Sui," the chronicle of a Chinese dynasty (597618), go was one of the three major pastimes enjoyed by early 7th-century Japanese (the other two were backgammon and gambling). In contrast to the documentary evidence from Chinese historical records, the popular belief in Japan is that go was brought directly from China in the year 735 by Kibi no Makibi, popularly known as Grand Minister Kibi. He was sent to the Tang capital of Chang-an with a commission from Emperor Shomu's daughter, who succeeded to her father's throne as the Empress Koken, to bring the best of Tang learning back to Japan. After 18 years in China, Kibi returned with a cargo of artifacts representing his choice of the best of Chinese culture. He also brought back a knowledge of go.

The magic of Go

Richard Bozulich

While go was undoubtedly one of many games enjoyed by the upper classes of early 7th-century Japan before Kibi's return from Chang-an, it is probable that when he informed those at the Imperial court of go's popularity at the Tang court, go was elevated to a special status, resulting in its establishment as a game worthy of the Japanese nobility. It is safe to say that while Kibi did not introduce go to Japan, he was responsible for its achieving the great prestige it has enjoyed here.

The development of go in Japan

In the 12th century, the warrior class supplanted the aristocracy as the effective rulers of Japan, and until the 17th century the country was engulfed in almost continual warfare. During this period, go was highly regarded by the warrior generals, some of whom believed that the study of its tactics and strategies was good moral and intellectual training for the operations of armies in the field. The three greatest Japanese warlords of the late 16th and early 17th centuries-Oda Nobunaga, Toyotomi Hideyoshi and Tokugawa Ieyasu-were devotees of go, and they all employed go teachers for themselves and their officers. In 1588, Nobunaga's successor, Toyotomi Hideyoshi, organized a large-scale competition to systematize the rankings of go players. Nikkai, a high-ranking Buddhist monk, who was Nobunaga's go teacher, won this competition and Hideyoshi decreed that from then on all other players should take black or a larger handicap from him. Nikkai was also awarded a stipend which began the government patronage that enabled go to flourish in Japan. At the beginning of the 17th century, four go houses were established: the Honinbo (of which Nikkai became the head, changing his name to Honinbo Sansa), Inoue, Yasui and Hayashi. These houses competed in the search for the most talented players and devoted great effort to the study and development of go theory and technique in order to surpass each other. Around the same time, in 1603, Tokugawa Ieyasu united Japan under the Tokugawa Shogunate. His government awarded stipends to the four go houses, established the office of Godokoro, held by Honinbo Sansa until his death in 1623, and instituted the annual castle games played in the presence of the shogun. The Godokoro was the top go post in the Edo-era go world. The holder of this office was the shogun's official go instructor. He also controlled promotions and the issuing of diplomas. In addition, the Godokoro decided pairings for the annual castle games and was responsible for all ceremonies connected with go, such as games played before the emperor and games with foreigners. Only the top player could become Godokoro, which meant that he would also be promoted to the ultimate rank of Meijin (master player). It is said that sometime in 1578 while Nobunaga was watching Nikkai play, he was so impressed with the latter's skill that he cried out "Meijin!'' This is apparently the origin of the term. It continues today as the name of one of the top three professional go titles.

The magic of Go

Richard Bozulich

Professional go in Japan

Although go was always esteemed by the upper classes in China and Korea, it was in Japan that it achieved its highest level of play and became widely popular with the masses. The game reached the zenith of its theoretical development at the end of the Edo period (1603-1868), but the prosperity it had achieved was swept away in the 1860s amid the confusion resulting from the collapse of the Tokugawa Shogunate. The system of government patronage it received was abolished in 1868, and the heads of the four go houses and their pupils found themselves adrift in a new world where ancient traditions were cast aside. Around 1880, interest in go was revived, this time under private auspices. Newspapers started publishing game records, and The Yomiuri Shimbun, nowadays a leading sponsor of go in Japan, was one of the first when it started publishing game records in 1885. By 1910, there were more than a dozen newspapers with go columns, and it became feasible to make a living as a go player again. In July 1924, the Japan Go Association was founded, and professional go in its current form began. Today, there are nearly 500 active professional players in Japan. Professional go players can make substantial earnings through game fees and prize money from the many tournaments they compete in. In addition, they can also earn money by officiating at tournaments, making TV appearances, teaching amateurs, and receiving royalties on books and videos. How does one become a professional go player? In Japan, the usual way is to become an apprentice at the Japan Go Association or the Western Japan Go Association. The associations usually accept only youngsters from age 5 to 18 who show exceptional talent. Every Saturday and Sunday, these young students compete with each other in a rating tournament. To qualify as professionals, they must work their way up to the upper echelons of the tournament. Out of 48 aspirants, only five are admitted to professional rank each year. Once apprentices have become professional, they start out at the rank of 1-dan. To rise above this rank, they play against other professionals in a rating tournament. The system for gaining promotion is complicated, but, in essence, if a player wins a certain percentage of an increasing number of games, he or she will be promoted to the next rank. The highest rank attainable is 9-dan.

Go in China

Despite having been invented in China, go has not always enjoyed a place of honor in that country. During the Cultural Revolution (1966-1976), go was out of favor with the zealous Red Guards, although the Chinese government officially supported about 30 go players, classed as "national sportsmen and sportswomen." It was not until 1981 that the current, well-supported professional system was initiated.

The magic of Go

Richard Bozulich

Over the past 38 years, however, there has been an active go exchange between China and Japan, consisting of goodwill tours featuring games between Japanese professionals and the top Chinese players. They began in 1960 and, with the exception of a six-year suspension from 1967 through 1972, have continued until the present. The rivalry between Japan and China took on a different character with the introduction in 1984 of the annual Japan-China Super Go knockout team match, which the Chinese won more often than not. In 1996, Japan's defeat was apparently so humiliating--nearly its entire team was wiped out by the 20-year-old Chang Hao--that the series was canceled. Regular tournaments and title matches were first held in the late 1970s. Today, there are a number of big titles, similar to those in Japan, with about 100 professionals competing for them. The strongest Chinese players are Chang Hao and Ma Xiaochun. Nie Weiping was the first Chinese player to seriously challenge Japanese supremacy in go. In the late 1970s, he consistently defeated some of the strongest Japanese players. On numerous occasions, he anchored the Chinese team in the Japan-China Super Go series to save China from defeat by beating the best players Japan could field. From the late 1980s, a new player, Ma Xiaochun, began to dominate the Chinese tournament scene. However, his supremacy is now being challenged by a new generation of players, the foremost of whom is Chang Hao, who is only 21. Last year, he defeated Ma Xiaochun in a major title match. Two other young professionals, Zhou Heyang, 22, and Wang Lei, 20, have achieved significant successes not only in Chinese tournaments but also in international tournaments. In spite of the short history of China's professional go system, there is no gap between the playing strength of the top Chinese players and that of the top Japanese and Korean players. How did the Chinese become so strong so fast? For one thing, the government sponsors go in public schools, so talented young players have a chance to compete for local and national titles at the primary, junior high and high school levels. In addition, Chinese professionals say that they have learned a lot from Japanese pros who acted as tutors during the early years of the Japan-China go exchanges. They also had available all the go theory that was developed in Japan over the last 400 years.

Go in South Korea

Although go was played in Korea long before it arrived in Japan, it is only since 1956 that it has been played professionally there. Go, called "paduk" in Korean, was traditionally regarded only as a pastime or a gambling game, but in 1980 it was officially recognized by the South Korean government as an important cultural asset. The (South) Korean Go Association was founded almost single-handedly in September 1955 by Cho Nam Chul.

The magic of Go

Richard Bozulich

Today, there are more than 150 professional players competing for prizes in 16 different tournaments, including eight newspaper tournaments and three TV tournaments. From the middle of the 1970s, the player who dominated the South Korean titles was Cho Hun Hyun, a ninth-dan. In his youth, Cho studied in Japan, but instead of making his career there, as did his compatriot Cho Chikun, he returned to South Korea with the intention of raising the strength of his countrymen. His efforts have borne fruit. His disciple Lee Chang Ho, at the age of 22, is clearly the strongest player in South Korea and some think the strongest in the world. He holds most South Korean titles as well as some important international titles. Another South Korean title-holder, Yoo Chang Hyuk, is also a disciple Cho Hun Hyun. Because of Lee Chang Ho's spectacular successes in domestic tournaments as well as in the international go arena, he has become a hero in his native land where he has ignited a huge following, somewhat like that of a rock star. This has caused a surge in the popularity of go in South Korea. Large South Korean companies have poured vast amounts of money into international tournaments and a legion of young prodigies are emerging. It has been predicted that in 10 years, South Korea will be the preeminent go-playing country in the world.

Go in Europe

Over the past few decades, go has become increasingly popular in the West, especially in the United States and Europe. In the United States, there are more than 120 go clubs, representing almost every state, while in Europe the European Go Federation brings together go organizations from both eastern and western Europe. The history of go in Europe began in 1900 with the founding of a go circle in a naval officer's club in Pula, a Croatian port in the Adriatic Sea. This club was apparently quite active, with about 200 members, and from here the game spread throughout Croatia, Slovenia and Austria. In the aftermath of World War I, only a nucleus of about 12 players were left, but they held regular meetings in Vienna until around 1939. Meanwhile, go had also established a foothold in Germany. A German engineer, Otto Korschelt, who had learned go from Honinbo Shuho while working in Japan, published a report on the game in a German journal around 1880. Based on this report, two introductory books on go were published around 1908. Around this time Prof. L. Pfaundler published a go magazine Deutsche Go Zeitung. But it had only about 50 readers and it was discontinued in about one year after publishing 10 issues. But in 1920, Bruno Ruger resumed publication in Dresden. It was published continuously until 1943 and provided unity to all go groups throughout Germany and Austria. In 1937, the German Go Association was founded. It was the first official nationwide go organization established outside of Asia and in 1938 it organized the first European Go Championship.

The magic of Go

Richard Bozulich

World War II effectively put a stop to most go activities in Europe, but by 1953 go clubs had sprung up in both the Netherlands and Britain and there was enough interest to warrant annual European go congresses. In 1958, the European Go Championship was restarted as part of the European Go Congress, and it has been held every year sincethen. By 1960, go clubs had sprung up in Yugoslavia and by the 1970s it had spread to France, Switzerland and Denmark. Today, go is played in 27 countries throughout western and eastern Europe. Each of these countries holds a national championship and the winner is usually entitled to go to Japan to represent his or her country in the World Amateur Go Championship. The responsibility of organizing inter-European go activities falls to the European Go Federation. The biggest and most important event is the European Go Congress that includes the European Open Championship. This event is held every year during the last week of July and the first week of August, and is usually attended by about 500 players. This year's congress will be held in Slovakia. Besides the go congress, the EGF organizes a tournament to determine the European who will play in the Fujitsu World Championship. It also organizes youth championships as well as many other tournaments. In 1992, the European Go Center was opened in Amstelveen, Netherlands. It was founded and financed by Kaoru Iwamoto who held the Honinbo title for two terms in the 1940s. The center is more than a venue where players can meet for games: it is also the main center for popularizing the game throughout Europe. It publishes books for beginners as well as teacher manuals and has had them translated into 16 European languages. It also actively promotes go in elementary schools, thereby ensuring that go will be an important game in Europe as well as in Asia in the next century.

International tournaments

With the emergence of Chinese and Korean go players who were clearly as strong as the top Japanese title holders, it became clear that a venue was needed in which all the top players in the world could compete against each other to determine who was the world's strongest player. The first professional international tournament was the Fujitsu Cup, first held in 1988 and dubbed the World Go Championship. In this tournament top players from all over the world vie for a 20,000,000 yen first prize. The following year, the Ing Cup was established by Ing Chang-ki, a Taiwanese industrialist. This event was held only once every four years, but the winner's prize was 400,000, dollars so it attracted a lot of interest. In 1990, the Tong Yang Securities Cup was transformed from being a solely Korean affair to an international tournament with a winner's prize of 120,000,000 won (about 91,000 dollars at today's exchange rate). In 1996, two tournaments were founded by Korean companies. The first was the LG Cup, offering a first prize of 200,000,000 won (about 152,000 dollars).

The magic of Go

Richard Bozulich

Quickly following on the heels of this tournament came the Samsung Cup, which offers a 400,000,000 won (about 304,000 dollars) first prize. This last tournament is unique in that it is an open tournament in which anyone can compete to join the seeded players in the main tournament. However, all competitors in the preliminaries must pay their own expenses, something previously unheard of in a professional tournament. For every win in the preliminaries, there is some prize money, about 1,000. dollars The big lure, however, is the 400,000 dollars prize for the winner. There is also a world championship tournament for women called the Bohai Cup. Since its inauguration in 1995, it has been dominated by Rui Naiwei, who is indisputedly the world's strongest woman go player. She has won this tournament three times, while her main rival, Feng Yun, has won it once. Both Rui and Feng are Chinese, but Rui now lives in the United States, where she teaches go and competes in various international tournaments. Her go strength is on the same level as the top male professionals. There is also an international TV tournament in which the finalists from the TV tournaments in China, Korean and Japan play a knockout tournament for the TV Asia Cup. The games of this tournament are broadcast live in the participants' countries. Each player must make a move within 30 seconds, but has 10 minutes free-thinking time.

World Amateur Go Championship

Every year, the World Amateur Go Championship, sponsored by Japan Airlines, is held in Japan. At the first championship in 1979, only 15 countries participated. In this year's event, held from June 8 to 11 in Oita, there were players from 55 countries, with five--Vietnam, Madagascar, Guatemala, Colombia and Peru represented for the first time. In the first championship, the countries outside of Asia that took part were mainly from Europe and North America. Argentina did send a player, but this year representatives from nine Central and South America countries took part. In Africa, go seems to be spreading in countries outside of South Africa as evidenced by Madagascar sending its first competitor. It was also reported by the South African representative that a large number of young people in the townships are regularly going to Johannesburg to take part in classes for beginners. The go situation in Madagascar is truly exciting. The organization there has 240 members, half of which are women. Two countries from the Middle East--Israel and Turkey--took part, and countries that one might not expect to participated, namely, North Korea and Yugoslavia, were also represented. Since participating countries must have a sufficient number of members to form an organization, the increase in the number of participating countries shows that go has truly become an international game. Indeed, go, with its 36 million players worldwide, may even exceed chess in popularity. 9

The magic of Go

Richard Bozulich

In past championships, the winner was usually from China or Japan. However, this year, for the second year in a row, South Korea took top place with eight straight wins. Japan was second with seven wins, while North Korea and Chinese Taipei were third and fourth, respectively. Canada took fifth place with six wins, while China also ended with six wins for seventh place, being nosed out by Hong Kong China on a point system called "sum of opponent's scores." The United States took the eighth-place slot, also with six wins. The most surprising and impressive result of the tournament was the 10th place taken by a teenager from Hungary. Fifteen-year-old Diana Koszegi also managed six wins in this tournament. Her two losses came from the eventual winner of the championship, Yoo Jae Sung of South Korea, and sixth-place finisher Kan Ying of Hong Kong China. Koszegi clearly has enormous talent, but she says her first goal is to finish high school. After that, she might try embarking on a professional career in go. One of the big attractions at this year's championship was a giant go board 40 meters square with each of the black and white styrofoam stones measuring two meters in diameter. Using this huge go board and stones, a game was played between Mayu Hosaka 2-dan and amateur Miyoshi Abe with about 150 people watching. Next year, the championship will be held in Sendai. We can expect the participation of at least one other country, Morocco, putting North Africa on the go map.

Women in go

One of the earliest references to women playing go in Japan can be found in "The Tale of Genji. Not only was this novel written by a women, the only go players in it were women. No doubt go was a popular pastime in the medieval court of the time, and the game was clearly enjoyed by women as well as men. Go playing was also one of the arts that many of the geisha of the Edo period mastered. Evidence for this is in the numerous woodblock prints of geisha featuring go as its main theme. Only a few women who played go professionally during the Edo period. The most famous was Sano Hayashi (1825-1901). As a child she showed sufficient talent for the game to be adopted by the Hayashi go house. By 1840 she had reached 1-dan and became 3-dan in 1846. She was an active player until 1890. Perhaps her most important legacy was in her disciple Fumiko Kita (1875-1950). Kita's father was a famous doctor who compiled the first Japanese-German dictionary, but, when he died, her mother gave her up for adoption to the Hayashi go school and Sano Hayashi became her adoptive mother. She became 1-dan in 1889 and eventually was awarded the rank of 6-dan, the highest rank ever attained by a woman at that time, and, when she died in 1950, she was posthumously awarded the rank of 7-dan. As a go player, being a woman was no handicap; she was clearly the equal of most of her male rivals.

10

The magic of Go

Richard Bozulich

She became famous and earned great respect by winning five straight games against male opponents on three different occasions. Kita is considered to be the mother of modern-day women's professional go. Virtually all female players who turned professional before World War II were taught by her. Before the war, only one or two women played go professionally, but now there are more than 50 female professional go players. One of the most promising postwar players is Izumi Kobayashi 3-dan (b. 1977). She is the daughter of Koichi Kobayashi 9-dan, (considered to be Japan's No. 2 player) and the late Reiko Kobayashi (nee Kitani) 7-dan, who was the daughter of the great Minoru Kitani. She has beaten many top-ranked players in open tournaments, and currently holds the Women's Kisei title. Many feel she will develop into a top player. Although she holds no title, Kikuyo Aoki 7-dan is another very promising as well as an ambitious competitor--she hopes to be the first woman to take a top open title. She came close when she played in the best-of-three match for the King of the New Star tournament two years ago. At present, she is challenging Terumi Nishida 5-dan for the Women's Meijin title. She has held a number of women's titles in the past, including the 1990 Women's Meijin title. In spite of Japan's long history of women go players, Chinese female players seem to be much stronger than their Japanese counterparts. The most stellar is Rui Naiwei 9-dan (b. 1963). She has defeated many top professionals in international tournaments, and she has won the Bohai Cup, a world championship tournament exclusively for women, three times. Rui emigrated to the United States a number of years ago with her husband, who is also a 9-dan. She is unaffiliated with any of the major go associations, so her appearances are limited to the international open tournaments and others that she is invited to participate in. Her results, however, would seem to indicate that she is among the 20 top players in the world. The other Chinese woman 9-dan is Feng Yun. She has won the Bohai Cup twice and has played in every final of that tournament that she has entered, but each time she faced Rui, she was convincingly defeated, indicating that, although the second strongest female player in the world, Rui is clearly a cut above her.

Go and computers

The year 1997 was a bad year for world chess champion Gary Kasparov-he was defeated by Deep Blue, an IBM computer designed to play chess. This result might lead you to believe that go would also be an easy game for a computer to play well. Its rules are few and simple. Unlike chess, with its different pieces and complicated rules, go is played only with equal-valued black and white stones, which would seem to make it compatible with the binary nature of computers. The object of go is to control more territory than your opponent, so the best move in any position is simply the one that gives the player of that move the maximum amount of territory-a simple counting procedure, a chore computers excel at. But it is not so easy.

11

The magic of Go

Richard Bozulich

Indeed, fewer than 100 lines of computer code are needed to program a computer to play go. Add a few more lines to the program and the computer will be able to evaluate the amount of territory controlled by each side. But when it comes to tactics and strategy, the best go-playing programs are not much stronger than a beginner. One reason chess can be programmed to such a high level is that it is essentially a tactical game in which material gain is important. The most sophisticated chess programs look ahead seven or eight moves to find the best way to give a material or a positional advantage. In go, however, material gains are strongly linked to strategic considerations. A tactical success, such as the capture of a large group in one part of the board, might be a game-losing blunder. Another factor that makes go more difficult to program than chess is the size of the board. On the standard 19 x 19 grid, there can be anywhere from 100 to over 300 possible moves to consider. Thus, making exhaustive whole-board searches, as chess programs do, is impractical. Moreover, considering that go players routinely look more than 10 moves deep, it would not make for a strong program. In most chess positions there are usually around 30 possible moves, and 95 percent of human players make oversights within a search horizon of three or four moves. If a computer is to play go well, it will not be able to rely on brute force; it will have to be programed to play intelligently. In other words, heuristics will have to constitute a large part of the program. In chess the two main heuristics are material gain and mobility. The problem in go is that there are so many principles that constitute a good move; there is no one dominating factor. The most likely candidate that comes to mind for an evaluation function is "size of territory." But to quantify the concept of territory is not so simple. Superficially, certain kinds of defensive moves may not seem to have a territorial meaning. In fact, in the short term they let one's opponent get more territory. But it is essential that they be played because they maximize the efficiency of other stones. Ultimately, such moves, if they are good, will translate into territorial gains elsewhere. In some positions, a group may not define territory, but it radiates influence that, with skillful play, can be turned into territory elsewhere. In other cases, moves must be made to maintain the integrity of a position. Such moves may seem to duplicate the work of the other stones in a particular locale, but if they are omitted, the local position could collapse. Of course, there are moves that directly take territory, but it is hard to instruct the computer to recognize when such moves should be made. Clearly, quantifying a general concept of territory for go, which a computer can understand, is not easy. It would be possible to compile heuristics for go, but they would give contradictory suggestions as to where a move should be played, so they would contribute little to increasing the strength of a go program. Strength in go relies too much on intuition and pattern recognition. These are the areas where computers, as yet, have almost no ability.

12

The magic of Go

Richard Bozulich

Because of go's complexity, it could provide the vehicle to help make important advances in artificial intelligence. Most applied-AI tasks take place in the real world, but this is a "noisy" domain that makes problems difficult to solve. Go has many features in common with the targets of applied AI and it also provides a clean environment in which to solve these problems. Although I am skeptical that computers will ever be able to compete on equal terms with even moderately strong amateur go players, the challenge of go might provide the impetus for many of the future advances that will be made in artificial intelligence.

Go online

In the past, if you wanted to play go, your only options would be to visit a go club or play with a friend at his home or yours. Today, however, the Internet offers a third option--playing online. There are a lot of advantages to playing go on the Internet. Since go is played in different time zones, you can always find an opponent day or night. There are a large number of players at all levels, from beginners to professionals, so you can easily find an opponent around your playing strength. You do not have to worry about equipment: the online graphics are superb with easy to follow instructions. And with the option of choosing from a number of computergenerated language modes, there are no language problems. There are a number of sites where you can play go, but the most popular is IGS, or the Internet Go Server at http://igs.joyjoy.net. At peak hours, there may be as many as 800 players logged on. Another site is the NNGS (No Name Go Server). Among Japanese-language sites, "San-san" is popular, and Toshiba Corp. has just opened its own go server, WWGo. A number of large Japanese companies are planning to launch similar servers, so these organizations will no doubt be spending a lot of money advertising their go servers, thereby promoting the popularity of the game. You can also play go on the Internet in Yahoo's gaming area (http://games.yahoo.com) and at Microsoft's MSN Gaming Zone (http://zone.msn.com). However, these two sites are not designed for the serious go player and are best for beginners who just want to get a few games under their belts. Online go is starting to cut into the clubs where go players have traditionally congregated. There has recently been a decline in membership, and new clubs are having a hard time attracting members. This trend has not been so noticeable in Japan where most players are of the older generation and are not as computer savvy as those in their 20s and 30s. But, as time goes by, this is bound to change. In contrast, most players in Europe and the United States are about college age, and this is the age group that is quite knowledgeable about computers and finding its way around the Internet. In spite of the decline in clubs, the go population in the United States and Europe seems to be increasing dramatically because of the Web.

13

The magic of Go

Richard Bozulich

Beginners can learn go on the Internet and weaker players can easily enjoy games with strong players who will instruct them, pointing out their mistakes and suggesting better moves. Since participants can use a pseudonym on the Web, beginners are spared the embarrassment of having their mistakes associated with their real names. The Web has also been a boon for the propagation of go among children. On the first Friday of every month, IGS runs a "cybercamp" where children can log on and play games with each other. Still, with all its advantages, Internet go seems to lack a human element. Go, like all games, is a social activity, and the anonymity of the Web does not lend itself well to human contact nor the friendships that so often comes from meeting an opponent face-to-face. Also lacking are the tactile feel of the stones and the resonant click they produce on the board when fine equipment is used. But whatever misgivings traditionalists such as myself might have about Internet go, playing go on the Web seems to be the wave of the future and is perhaps best way for go to become a major game in the West.

The Yomiuri Shimbun, 1999

14

Você também pode gostar

- Slave Girl in ChineseDocumento1 páginaSlave Girl in ChineseJennifer BallAinda não há avaliações

- Appendix Being and Time TravelDocumento9 páginasAppendix Being and Time TravelSolángel RoccocuchiAinda não há avaliações

- The Dialogues of PlatoDocumento2.157 páginasThe Dialogues of PlatoanonaymoosAinda não há avaliações

- Beyond Good and Evil - F. NietzscheDocumento250 páginasBeyond Good and Evil - F. NietzscheSiddharthaGuatamaAinda não há avaliações

- Ngaunts5x8 With CoverDocumento116 páginasNgaunts5x8 With CoverTristan TkNyarlathotep Jusola-SandersAinda não há avaliações

- Card Repertory CompleteDocumento7 páginasCard Repertory CompleteRahul RamanAinda não há avaliações

- Longevity: HistoryDocumento7 páginasLongevity: HistorytechzonesAinda não há avaliações

- The Game of GODocumento27 páginasThe Game of GOsaffwan100% (1)

- Sayings of BuddhaDocumento305 páginasSayings of Buddhapeter911xAinda não há avaliações

- Of Futility Decay Compilation of TextsDocumento116 páginasOf Futility Decay Compilation of Texts0000000000Ainda não há avaliações

- The Simple Magic of Homeopathic InductionDocumento4 páginasThe Simple Magic of Homeopathic InductionGianna Barcelli FantappieAinda não há avaliações

- Piccione SenetDocumento4 páginasPiccione SenetAlfonsoMontagni100% (1)

- Scroll of Shongto - The COS 9 Page Fun Print and Tape and Roll Up Taoist ScrollDocumento9 páginasScroll of Shongto - The COS 9 Page Fun Print and Tape and Roll Up Taoist ScrollshangtsungmakAinda não há avaliações

- DR Shah Homeopathic Doctor For Best TreatmentDocumento7 páginasDR Shah Homeopathic Doctor For Best TreatmentlifeforcehomeopathyAinda não há avaliações

- The Maya Apocalypse and Its Western RootsDocumento169 páginasThe Maya Apocalypse and Its Western RootsGowolAinda não há avaliações

- Miasms, Nosodes and Essences by Peter MorrellDocumento12 páginasMiasms, Nosodes and Essences by Peter Morrellsergiomiguelgomes9923Ainda não há avaliações

- Life After DeathDocumento7 páginasLife After Deathanon-159884100% (1)

- Walk On WaterDocumento4 páginasWalk On Waterjoebob19Ainda não há avaliações

- Hymn of Isis and Osiris ReportDocumento18 páginasHymn of Isis and Osiris ReportJohn Matthew CruelAinda não há avaliações

- Mahavira's TeachingsDocumento6 páginasMahavira's TeachingsH.J.PrabhuAinda não há avaliações

- Alexander PushkinDocumento7 páginasAlexander Pushkinapi-38426080% (1)

- The Human Person As An Embodied SpiritDocumento31 páginasThe Human Person As An Embodied Spiritjljakelee1003Ainda não há avaliações

- Ovid MetamorphosisDocumento1.363 páginasOvid MetamorphosisJake Simon100% (1)

- The Symbolism of ChessDocumento6 páginasThe Symbolism of ChesssakhoibAinda não há avaliações

- The Day View Opposite The Night View-English-Gustav Theodor FechnerDocumento208 páginasThe Day View Opposite The Night View-English-Gustav Theodor Fechnergabriel brias buendiaAinda não há avaliações

- Mecidine in EgypttDocumento25 páginasMecidine in Egypttemmanuella otaAinda não há avaliações

- BHAGWAD GITA-consequentialism Vs Non ConsequentialismDocumento3 páginasBHAGWAD GITA-consequentialism Vs Non ConsequentialismPrakhar Nema100% (1)

- The Roman Origins of HalloweenDocumento3 páginasThe Roman Origins of HalloweenGabriela MejiaAinda não há avaliações

- PDFDocumento222 páginasPDFmbutelmanAinda não há avaliações

- Penelope GreekDocumento3 páginasPenelope Greekchappy_leigh118Ainda não há avaliações

- Buddhist Hybrid Sanskrit Grammar and Dictionary, Vol. 1 Grammar PDFDocumento261 páginasBuddhist Hybrid Sanskrit Grammar and Dictionary, Vol. 1 Grammar PDFVo Thutruoc100% (2)

- Cleary Samurai Wisdom PDFDocumento257 páginasCleary Samurai Wisdom PDFEdwin WellingerAinda não há avaliações

- The Human EgoDocumento35 páginasThe Human Egohmxa91Ainda não há avaliações

- A Thousand BooksDocumento58 páginasA Thousand Booksashok kulkarni100% (3)

- Analysis of Serial Experiments Lain 2Documento22 páginasAnalysis of Serial Experiments Lain 2Michael CrawfordAinda não há avaliações

- BlancoMourelle Columbia 0054D 14014 PDFDocumento261 páginasBlancoMourelle Columbia 0054D 14014 PDFruyaaliiqAinda não há avaliações

- The Casket of MedicineDocumento104 páginasThe Casket of Medicinejivasumana100% (4)

- Interview With Frank Herbert and Beverly Herbert by Willis E. McNellyDocumento25 páginasInterview With Frank Herbert and Beverly Herbert by Willis E. McNellyMattYancik100% (1)

- The Essays of Arthur Schopenhauer Religion, A Dialogue, Etc. by Schopenhauer, Arthur, 1788-1860Documento46 páginasThe Essays of Arthur Schopenhauer Religion, A Dialogue, Etc. by Schopenhauer, Arthur, 1788-1860Gutenberg.orgAinda não há avaliações

- The Tradition of Stephanus Byzantius PDFDocumento17 páginasThe Tradition of Stephanus Byzantius PDFdumezil3729Ainda não há avaliações

- What They Said: Quotes From Over Two Thousand Years of Go HistoryDocumento6 páginasWhat They Said: Quotes From Over Two Thousand Years of Go Historydsaads adssdaAinda não há avaliações

- Study Guide: Ishikawa Jun "Moon Gems" (Meigetsushu, 1946)Documento4 páginasStudy Guide: Ishikawa Jun "Moon Gems" (Meigetsushu, 1946)BeholdmyswarthyfaceAinda não há avaliações

- Kwaidan - Stories and Studies of Strange ThingsNo EverandKwaidan - Stories and Studies of Strange ThingsNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (142)

- ShogiDocumento5 páginasShogiannca7Ainda não há avaliações

- (Go Igo Baduk Weiqi) The Classics of WeiqiDocumento37 páginas(Go Igo Baduk Weiqi) The Classics of Weiqiapi-3737188100% (2)

- Secrets of Chinese Divination: A Beginner's Guide to 11 Ancient Oracle SystemsNo EverandSecrets of Chinese Divination: A Beginner's Guide to 11 Ancient Oracle SystemsAinda não há avaliações

- Haunted Japan: Exploring the World of Japanese Yokai, Ghosts and the ParanormalNo EverandHaunted Japan: Exploring the World of Japanese Yokai, Ghosts and the ParanormalNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (4)

- (Go Igo Baduk Weiqi) I B S C - Guide of Korean BadukDocumento12 páginas(Go Igo Baduk Weiqi) I B S C - Guide of Korean BadukDiego EslavaAinda não há avaliações

- Ledyard - Galloping Along With The HorseridersDocumento39 páginasLedyard - Galloping Along With The HorseridersIngrid FeierAinda não há avaliações

- Seikyo Yoroku 2Documento24 páginasSeikyo Yoroku 2Cemec CursosAinda não há avaliações

- Guan-Yu the Hero: Romance of the Three Kingdoms (??, ??????)No EverandGuan-Yu the Hero: Romance of the Three Kingdoms (??, ??????)Ainda não há avaliações

- The Last King of Shang, Book 1: Based on Investiture of the Gods by Xu Zhonglin, In Easy Chinese, Pinyin and English: The Last King of Shang, #1No EverandThe Last King of Shang, Book 1: Based on Investiture of the Gods by Xu Zhonglin, In Easy Chinese, Pinyin and English: The Last King of Shang, #1Ainda não há avaliações

- Pathways of A Hidden LineageDocumento7 páginasPathways of A Hidden LineageSean AskewAinda não há avaliações

- Far Eastern Fox LoreDocumento34 páginasFar Eastern Fox Loreardeegee100% (1)

- Kwai DanDocumento267 páginasKwai DanIH InanAinda não há avaliações

- The First Quality Books To ReadDocumento2 páginasThe First Quality Books To ReadMarvin I. NoronaAinda não há avaliações

- Task 1 Methods in Teaching LiteratureDocumento2 páginasTask 1 Methods in Teaching LiteratureJaepiAinda não há avaliações

- Rulings On MarriageDocumento17 páginasRulings On MarriageMOHAMED HAFIZ VYAinda não há avaliações

- Press ReleaseDocumento1 páginaPress Releaseapi-303080489Ainda não há avaliações

- Resume - General Manager - Mohit - IIM BDocumento3 páginasResume - General Manager - Mohit - IIM BBrexa ManagementAinda não há avaliações

- How We Organize Ourselves-CompletedupDocumento5 páginasHow We Organize Ourselves-Completedupapi-147600993Ainda não há avaliações

- مذكرة التأسيس الرائعة لغة انجليزية للمبتدئين?Documento21 páginasمذكرة التأسيس الرائعة لغة انجليزية للمبتدئين?Manar SwaidanAinda não há avaliações

- Shipping Operation Diagram: 120' (EVERY 30')Documento10 páginasShipping Operation Diagram: 120' (EVERY 30')Hafid AriAinda não há avaliações

- TSH TestDocumento5 páginasTSH TestdenalynAinda não há avaliações

- Perception On The Impact of New Learning Tools in Humss StudentDocumento6 páginasPerception On The Impact of New Learning Tools in Humss StudentElyza Marielle BiasonAinda não há avaliações

- Gender Religion and CasteDocumento41 páginasGender Religion and CasteSamir MukherjeeAinda não há avaliações

- Selfishness EssayDocumento8 páginasSelfishness Essayuiconvbaf100% (2)

- 1.3 Digital Communication and AnalogueDocumento6 páginas1.3 Digital Communication and AnaloguenvjnjAinda não há avaliações

- AIW Unit Plan - Ind. Tech ExampleDocumento4 páginasAIW Unit Plan - Ind. Tech ExampleMary McDonnellAinda não há avaliações

- Erotic Massage MasteryDocumento61 páginasErotic Massage MasteryChristian Omar Marroquin75% (4)

- Chuyen de GerundifninitiveDocumento7 páginasChuyen de GerundifninitiveThao TrinhAinda não há avaliações

- Phrygian Gates and China Gates RecordingsDocumento1 páginaPhrygian Gates and China Gates RecordingsCloudwalkAinda não há avaliações

- Scholarly Article: Ritam Mukherjee: Post-Tagore Bengali Poetry: Image of God' and SecularismDocumento6 páginasScholarly Article: Ritam Mukherjee: Post-Tagore Bengali Poetry: Image of God' and SecularismbankansAinda não há avaliações

- John Dee - Sigillum Dei Aemeth or Seal of The Truth of God EnglishDocumento2 páginasJohn Dee - Sigillum Dei Aemeth or Seal of The Truth of God Englishsatyr70286% (7)

- Merger of Bank of Karad Ltd. (BOK) With Bank of India (BOI)Documento17 páginasMerger of Bank of Karad Ltd. (BOK) With Bank of India (BOI)Alexander DeckerAinda não há avaliações

- Laurel VS GarciaDocumento2 páginasLaurel VS GarciaRon AceAinda não há avaliações

- Causing v. ComelecDocumento13 páginasCausing v. ComelecChristian Edward CoronadoAinda não há avaliações

- Final DemoDocumento14 páginasFinal DemoangieAinda não há avaliações

- Decretals Gregory IXDocumento572 páginasDecretals Gregory IXDesideriusBT100% (4)

- Literary Terms Practice Worksheet 3Documento11 páginasLiterary Terms Practice Worksheet 3Jiezl Abellano AfinidadAinda não há avaliações

- Ponty Maurice (1942,1968) Structure of BehaviorDocumento131 páginasPonty Maurice (1942,1968) Structure of BehaviorSnorkel7Ainda não há avaliações

- Ready For First TB Unit3Documento10 páginasReady For First TB Unit3Maka KartvelishviliAinda não há avaliações

- Fouts Federal LawsuitDocumento28 páginasFouts Federal LawsuitWXYZ-TV DetroitAinda não há avaliações

- Short Tutorial On Recurrence RelationsDocumento13 páginasShort Tutorial On Recurrence RelationsAbdulfattah HusseinAinda não há avaliações

- Schemes and Tropes HandoutDocumento6 páginasSchemes and Tropes HandoutJohn LukezicAinda não há avaliações