Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

Collecting Photographs

Enviado por

SolomonDireitos autorais

Formatos disponíveis

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Collecting Photographs

Enviado por

SolomonDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Collecting Photographs

A Short Guide On A Long Subject

Mary Street Alinder was Ansel Adams's chief of staff for five years until his death in 1984. She wrote the definitive Ansel Adams, A Biography and lectures on Adams at museums and universities around the world. James Alinder was a university professor of photography and Executive Director of The Friends of Photography in Carmel and San Francisco for eleven years. He is the author or editor of more than thirty photography books. The only good reason to buy a photograph is because you love it. Everything else, especially the question of investment, must be secondary. Of course, no one wants to purchase a work of art and lose money. The key is to know as much as you possibly can about the medium and about that artist, then follow your instincts. Photography is especially great to collect because the prices, even for the work of acknowledged masters, are very reasonable when compared to many other art forms. Excellent images by younger photographers can be bought for as little as $250 apiece. Works by the great masters are often only a few thousand dollars. But, because photography is such a new art, there are fewer established guides and the vocabulary is still being defined. Take "vintage," a word flung casually about by both dealers and collectors, and most often wrongly applied to any older print by an artist. More correctly, a vintage photograph is a print made very close in time to the making of the negative itself. Generally, it means that the print was made within a few years of the negative. Let's use an image by the photographer, Ansel Adams, as an example. On November 1, 1941 at 4:49:20 Mountain Standard Time, Adams created perhaps his most famous negative, Moonrise, Hernandez, New Mexico. He made the first two prints from that negative some time between December and February,1942. These closely reflected his original visualization of the scene before his lens on that November day. Adams made only a few prints of Moonrise, but to fill outstanding orders for it and to provide gifts for his dearest friends, in December of 1948 he went into his darkroom and made about twelve. This proved to be just the beginning. Adams was an artist who printed to order and Moonrise provoked a clamor like none other of his photographs. Decades later, Adams announced that he would stop taking print orders as of December 31, 1975, perhaps spurred on more than anything else because he did not want to have make one more Moonrise, which, as luck would have it was the most difficult to print of all 40,000 of his negatives. Photography began coming into its own as a collectible art in the 1970s as thousands of college students graduated and began earning enough to luxuriate in "disposable income." Many of these former students had studied photography or been exposed to it in museums and through the burgeoning market of photographic books. Photography, also, was refreshingly low-priced. In 1948, Adams charged $50 for a 16x20-inch print of Moonrise. In 1975, his price had risen to $1,200. Today, consider yourself lucky to find a Moonrise (in superb condition, of course) for $25,000. Most of Ansel's Moonrise prints were made and sold in the 1970s to accommodate this new collector interest in photography. The last were printed in 1980 and 1981 for a project he termed the Museum Set. These rarely find their way to market. Moonrise's made before 1948 can certainly be termed vintage. Generally a strict, but good rule is to say that a print made within three years of the negative is vintage. Moonrise's made between 1948 and the 1960s are "older." A Moonrise from the 1970s is often called a

modern or later print. Vintage does not mean better; it is the artist's initial interpretation of the negative. There are collectors who believe that the artist's first understanding is the most important. Vintage prints usually sell at a substantial premium over later prints. But Adams, for one, would be the first to campaign for his latest print, believing that everything he had learned through the many years of printing the negative added up to a stronger finished print than his first attempts. Generally speaking, most contemporary photographers issue their photographs in limited editions, but this has not always been the case. Traditionally, the number of photographs has been limited by the death of the photographer, who can no longer sign prints. In some cases prints are made from the negative after the artist's death by their family or Trust; Edward Weston and Imogen Cunningham are two examples. These prints will never have the value of artist made/signed photographs. In 1932, a band of friends formed a photography club of sorts that they called Group f/64. Led by Edward Weston, Imogen Cunningham, Ansel Adams and Willard Van Dyke, they issued a manifesto demanding that photographers maximize the medium's potential. The prevalent style for many years had been pictorialism, where the photographic print was manipulated to look more like an etching, charcoal or painting -- already recognized arts. Photography still held the title of Cinderella but longed to dance with the prince at the ball (translation: demanded to be acknowledged as an art form itself). Group f/64 proclaimed the only way for photography to assume its rightful position in the arts was to celebrate its own strengths: the sharpness of imagery that a lens can provide; a broad range of tonalities from black to white and all "zones" of gray in-between; depth of field, total focus from near objects to the far distant; and multiplicity. This last trait has long been seen as a primary strength in photography. Theoretically, an infinite number of prints can be made from a negative. This does not mean that most great photographs are "mass-produced." When he pulled his Moonrise negative from the vault and placed it in his enlarger, it often took Ansel Adams days to achieve one print that would be satisfactory to him. Trained as a classical pianist, he often used musical analogies to explain photography. He described a negative as a musical score and each print would be his new performance of that score. In photography, each print is as unique as a fingerprint. No matter how much two prints might look the same, they are never identical. But as photography entered the world of museums and galleries and collecting, the rules of other media began to bear. Collectors became concerned that there could be so many prints out of an image. And, indeed, since Moonrise was Adams most sought after work, he made the most prints of it, approximately 1,300 in all sizes, but mainly 16x20-inches. But this must be placed in context where Picasso would sign his name to editions of 10,000 or more lithographs. The numbers of Moonrise are most definitely finite as with every year, fewer are available as more and more come to reside in permanent museum and corporate collections. There are way more people in this world -- from China to Switzerland, from South Africa to America -- who yearn for an original print of Moonrise, made by the master, himself, than there are prints of Moonrise. When Adams died in 1984, that was it. No more Moonrise's, or Monolith's, or Mt. Williamson's. All of his negatives were picked up in a highly insured and air conditioned "art" delivery truck and transported to his archive at the Center of Creative Photography, University of Arizona, Tucson. There, if enough permissions are granted, a student can study his negatives under highly supervised conditions. The University is not allowed by contract to allow the making of any prints for sale. The one exception is that a handful of Yosemite negatives are still printed by an assistant to be sold in Yosemite as good quality souvenirs. These prints are approximately 8x10-inches and are clearly stamped on the verso of the mount as "Special Edition Prints." In 1974, when Adams issued Portfolio VI, ten fine, signed gelatin-silver prints in an edition of 110, over drinks a young photographer convinced him that he must start limiting all of his photographs. That night, Adams ran a Wells Fargo check canceller through all ten negatives. He awoke the next morning and rued his actions. He knew that he had betrayed one of his cardinal beliefs, and a tenet of Group f/64: the strength of the multiple. For so many years, people could afford to buy his prints just because he had not limited

their numbers. He was never a snob about art and certainly not about his own photography. He was happy to sell his prints to whomever wanted one. Today, one can still purchase an original Cartier-Bresson photograph. One of the greatest photojournalists of all times, Cartier-Bresson is still alive and signing prints. From a completely different photographic tradition than Adams, Cartier-Bresson does not make his own prints. He has been most concerned with the content of an image, not with making the fine print. The only reason that I can buy a print of Behind the Gare St. Lazare to hang on my wall is that the artist never limited the number of prints. I don't have any idea how many of those prints have been made and sold. It would be nice to know, but Cartier-Bresson is not saying. In the end, I have the photograph because I love that photograph. And, I do realize, that down the line, when Cartier-Bresson floats up to Leica heaven, that will be that. No more infinite possibility, just what there is. Another living master of photography, though much younger than Cartier-Bresson, is Jerry N. Uelsmann. In his sixties, Uelsmann, like almost all of his contemporaries has never limited his editions. As he says, even with all his recognition, from hundreds of museum exhibitions to over ten monographs of his work, most collectors want to purchase the same ten images. What would he have done if he had limited those ten? He could not have made it financially as an artist, even though in his case (as in the case of most artists), his primary means of support was as a college professor. At the same time, we counsel younger photographers to limit their editions. The times seem to call for it. On the positive side, the photographer does not need to arrive at the point of perpetual frustration that seemed to plague Adams when every new order for Moonrise arrived. A step-up in prices occurs as a certain percentage of the edition is sold. Using the photographs of California photographer, Chip Hooper, for example, his editions total 90 gelatin-silver prints in all sizes. He prints most of his large format negatives in 8x10-inch, 16x20-inch and 20x24-inches. 8x10 prints in the first group numbered from 1-20 are $350. The same size print numbered 21-40 is $450, and numbers 41-60 are $550. Numbers 61-80 are $650, and the price of the last ten is yet to be determined. The prices are raised as the edition sells out and the photograph becomes more rare.

The Ten Commandments of Buying a Photograph

1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. 9. 10. Thou must love it Thou must realize that thou are now the steward of that photograph Thou must learn everything that thou canst about the photographer Thou must have knowledge that the seller is of the highest repute, who will when possible provide you with provenance, the history of that print Thou must know the photograph's process and its likely stability Thou must be assured that it is an original photograph and not a "fine" lithographic reproduction Thou must know if the photograph is from a limited edition and, if not, how many prints of the image exist or could there be Thou must receive a certificate of authenticity from the seller Thou must learn how to care for the print Thou must know how to frame and display the photograph.

Você também pode gostar

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeNo EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (5794)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceNo EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (895)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)No EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Nota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (98)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingNo EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (400)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerNo EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (271)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItNo EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (838)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyNo EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (2259)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureNo EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryNo EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnNo EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (234)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaNo EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (266)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersNo EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (345)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaNo EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreNo EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)No EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Nota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (121)

- Christopher Walter. Theodore, Archetype of The Warrior Saint. Revue Des Études Byzantines, Tome 57, 1999. Pp. 163-210.Documento49 páginasChristopher Walter. Theodore, Archetype of The Warrior Saint. Revue Des Études Byzantines, Tome 57, 1999. Pp. 163-210.Patrologia Latina, Graeca et OrientalisAinda não há avaliações

- CultureDocumento55 páginasCultureRajiv KumarAinda não há avaliações

- Agapae 2017Documento44 páginasAgapae 2017api-403618226Ainda não há avaliações

- Stone WashDocumento3 páginasStone WashMuhammad MustahsinAinda não há avaliações

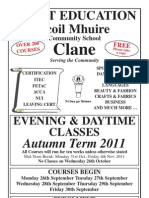

- Scoil Mhuire Clane - Autumn 2011Documento40 páginasScoil Mhuire Clane - Autumn 2011gerrymcgowanAinda não há avaliações

- Soft SuedeDocumento3 páginasSoft SuedeMakv2lisAinda não há avaliações

- Gimp Manual English PDFDocumento951 páginasGimp Manual English PDFJoseEspanAinda não há avaliações

- Tactica y Estrategia - Stan AllenDocumento1 páginaTactica y Estrategia - Stan AllenbelpcAinda não há avaliações

- The Argive Heraeum - Waldstein, Charles, Sir, 1856-1927Documento544 páginasThe Argive Heraeum - Waldstein, Charles, Sir, 1856-1927Grypas Sp100% (1)

- Ancient Greek ArtDocumento42 páginasAncient Greek Artkarina AlvaradoAinda não há avaliações

- Arts DLP 1Documento3 páginasArts DLP 1Pat HortezanoAinda não há avaliações

- Constellation Making RubricDocumento4 páginasConstellation Making RubricXynaAinda não há avaliações

- Office of The Sangguniang Kabataan: SK Funds P 30,000.00Documento3 páginasOffice of The Sangguniang Kabataan: SK Funds P 30,000.00Hello WorldAinda não há avaliações

- A Frame CabinDocumento3 páginasA Frame Cabinmondomondo75% (4)

- Cho - Interpretive Issues in Performing The Piano Suite "Goyescas" by Enrique GranadosDocumento119 páginasCho - Interpretive Issues in Performing The Piano Suite "Goyescas" by Enrique GranadosMauricio Albornoz GuerraAinda não há avaliações

- Describing Cities and PlacesDocumento3 páginasDescribing Cities and PlacesMalejandra Rivera BarreraAinda não há avaliações

- About School LifeDocumento5 páginasAbout School Lifekarthika4aAinda não há avaliações

- BDJC B B Herringbone FlowersDocumento5 páginasBDJC B B Herringbone Flowerscamicarmella100% (4)

- Vol. 01 PDFDocumento306 páginasVol. 01 PDFIlia RodovAinda não há avaliações

- Victorian PoetsDocumento567 páginasVictorian PoetsDea FieldAinda não há avaliações

- Estrutura Da Lua I PDFDocumento3 páginasEstrutura Da Lua I PDFLina CésarAinda não há avaliações

- Rennie Bottali & Sheralee BottaliDocumento5 páginasRennie Bottali & Sheralee BottaliSheralee BottaliAinda não há avaliações

- Saic-W-2xxx-15 Pre Welding & Joint Fit-Up InspectionDocumento4 páginasSaic-W-2xxx-15 Pre Welding & Joint Fit-Up InspectionAnsuman Kalidas100% (1)

- Einstein, Picasso, and Cubism: Seeing' The Fourth DimensionDocumento2 páginasEinstein, Picasso, and Cubism: Seeing' The Fourth DimensionAna LucaAinda não há avaliações

- Typographic Rules 1-10Documento11 páginasTypographic Rules 1-10Robert LieuAinda não há avaliações

- 250 Yonge Building SpecificationsDocumento5 páginas250 Yonge Building SpecificationskuchowAinda não há avaliações

- SAi Production Suite 12 Readme PDFDocumento16 páginasSAi Production Suite 12 Readme PDFEmersonSilva0% (1)

- Contemporary Arts Module 3.docx 1 1Documento24 páginasContemporary Arts Module 3.docx 1 1Sydney CagatinAinda não há avaliações

- Color ConversionDocumento29 páginasColor Conversionsofyan_shahAinda não há avaliações

- DBZ MonopolyDocumento18 páginasDBZ Monopolyapi-326542433Ainda não há avaliações