Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

RESEARCH PROPOSAL SAMPLE On Women Empowerment and Micro Finance

Enviado por

Jonathan AliogoDescrição original:

Título original

Direitos autorais

Formatos disponíveis

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

RESEARCH PROPOSAL SAMPLE On Women Empowerment and Micro Finance

Enviado por

Jonathan AliogoDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

RESEARCH PROPOSAL SAMPLE - BY MUTALE TRICIA

RESEARCH PROPOSAL

IMPACT OF MICRO FINANCE INSTITUTIONS ON WOMEN EMPOWERMENT IN ZAMBIA By Mutale Tricia Bwalya

Background Information Micro Finance Institutions (MFIs) are organizations which were originally set up in order to help finance those small

scale micro-enterprises and local economic activities which were largely excluded from formal finance and mainstream banking practice. However, in Sub-Saharan Africa, microfinance is not yet widespread and most low income earners, including many of the poor, cannot access financial services (CGAP, 2009; Spencer & Wood, 2005) while poverty is officially widespread and acute (World Bank, 2009). There are also significant disparities in the level of development and performance across different countries (MIX, 2010). While the developed micro finance institutions (MFIs) of South Asia and Latin America are challenged to become more commercially viable, emerging often donor dependent - MFIs in sub-Saharan Africa can struggle to survive. Inexperienced staff, questionable working practices, poor internal controls, substandard governance (Mersland

and Strom, 2009; Hartarska, 2005) and inadequate management information systems all contribute to African MFI underperformance (CGAP, 2009). In Zambia, for example, a lack of competent and skilled human capital has been identified as a particular failing ploblem facing micro institutions in Zambia (Microfinance Africa, May 2010). In Zambia, Siwale (2006) previously scrutinized Christian Enterprise Trust of Zambia (CETZAM)s near collapse and observed how its subsequent restructuring embraced policy and senior management, product diversification, and further grassroots staff changes in branches. Similarly, Moroccan MFIs were found to lack the necessary skills, knowledge and experience with some being accused of fraud and embezzlement of depositors funds. Studies elsewhere suggest that many crises are not just random, one off events

apart, but originate in serious, and maybe also potentially predictable and/or avoidable, management and intelligence failings (Vaughan, 1996). Under performance shadows MFI development in Southern Africa (Lafourcade, Isern,

Mwangi, & Brown, 2005; Chiumya, 2006; Dixon, et al, 2007) and formal evaluations of impact assessment, program replication, client outreach and financial sustainability (Copestake, 2002) typically suggest that progress here lags significantly behind that which has been claimed for South Asia and Latin America (MIX, 2010; Basu, Blavy, & Yulek, 2004).

1.2 Statement of the Problem Despite many international agreements affirming their human rights, women are still much more likely than men to

be poor and illiterate. They usually have less access than men to medical care, property ownership, credit, training and employment. They are far less likely than men to be politically active and far more likely to be victims of domestic violence. Therefore the study is aimed at examining the impact of Micro Finance Institutions on women empowerment in Zambia. 1.3 HYPOTHESIS It has been hypothised that micro Finance Institutions are ineffective in empowering women in Zambia.

LITERATURE REVIEW

The roles that men and women play in society are not biologically determined -- they are socially determined, changing and changeable. Although they may be justified as being required by culture or religion, these roles vary widely by locality and change over time. Girl Guide Association has found that applying culturally sensitive approaches can be key to advancing womens rights while respecting different forms of social organization. Addressing womens issues also requires recognizing that women are a diverse group, in the roles they play as well as in characteristics such as age, social status, urban or rural orientation and educational attainment. Although women may have many interests in common, the fabric of their lives and the choices available to them may vary widely. Girl Guide Association seeks to identify groups of women who

are most marginalized and vulnerable (women refugees, for example, or those who are heads of households or living in extreme poverty), so that interventions address their specific needs and concerns. This task is related to the critical need for sex-disaggregated data, and UNFPA helps countries build capacity in this area of Women Empowerment and in the promotion of all rights for all. Empowerment of women has been identified as a valuable attribute, one that is essential to the effective functioning of an organization (Palmier, 1998). Theoretical discussions about structural power and its relationship to the development of empowerment in employees are abundant in the literature (Kanter, 1993; Kluska, Laschinger-Spence & Kerr, 2004; Sui, Laschinger & Vingilis, 2006).

Empowerment has also been shown to be essential to the

goals and outcomes of shared governance models (Anthony, 2004; Erickson, Hamilton, Jones & Ditomassi, 2003). Empowerment is evidenced by organizational members who are inspired and motivated to make meaningful

contributions and who have the confidence that their contributions will be recognized and valued. Impact of lack of women Empowerment in Zambia As women are generally the poorest of the poor ... eliminating social, cultural, women in the political is a and economic of

discrimination eradicating

against

prerequisite of

poverty

context

sustainable

development. International Conference on Population and Development (ICPD) Programme of Action, 1994. The third Millennium Development Goal (MDG), promoting gender equality and the empowerment of women, has given

prominence to recent efforts to target gendered poverty. Gendered poverty is the recognition that women and men face poverty for different reasons and both experience and respond to it differently. Studies have revealed that the indicators of education and literacy, the metrics used to measure progress towards MDG 3, do not sufficiently capture gendered poverty or gender disparities. There are many other factors that influence the status of women, such as income, reproductive health and environmental and socio - cultural constraints. Bradshaw and Lingerer (2003, in Chant, 2003) list three factors that contribute to the relative poverty of women: (1) women generally have fewer opportunities to transform work into income, (2) women still have limited decision-making

authority, and (3) when women actually do make decisions, they tend to act for the benefit of others first. Micro finance in a Zambian Context Zambian MFIs donor dependence (Bateman,2010) has potentially serious implications. For example, Musona (2002), Chiumya (2006), and Dixon etal (2007) reveal how relatively high operating costs, delinquency and default, low client intake/retention, potential fraud, and high staff turnover impede sustainability, and much vaunted outreach levels have been lagging behind East Africa for example. This high dependence on donor funds that can be found in many sectors in Zambia is particularly damaging in microfinance, where financial sustainability is of

fundamental importance.

Indeed, many face important management and corporate governance challenges. Major Zambian MFIs, except for FINCA, have struggled to reach desired client numbers (fig 1.0). As early as 2002, certain donor driven MFIs nevertheless maintained that market-based approaches could transform this situation even though most Zambian MFIs were only just founded in the late 1990s (Siwale, 2006). Since then microfinance has not grown in line with outside expectation (see figure 1.0 regarding major MFIs) and Chiumya (2006) indeed identified rising signs of its possible stagnation and contraction. The PZ case is therefore broadly emblematic of microfinance development at large and indicative of the threats posed to it. Zambian MFIs might potentially provide much needed, but hitherto scarce, financial services in a country where, even

by prevailing standards, access remains extremely low (FinScope, 2010; Mattoo and Payton, 2007). The Association of Microfinance Institutions of Zambia (AMIZ) has estimated that the industrys outreach is in the region of 250,000 to 300,000 active borrowers (largely due to an influx of new consumption based MFIs). 19 out of 25 licensed MFIs founded in the last 5 years have indeed been expressly consumer lending based. Since these MFIs do not emphasize small scale enterprise development they simply require formal employment before making a loan. However, an estimated 60,000 borrowers occupy the same enterprise loan market niche in which PZ operated. Additionally, the scope of services has also been particularly limited, with little savings mobilization to date (Dixon, Ritchie, & Siwale, 2006).

The law however has changed following the 2006 Banking and Financial Services (micro-finance) Regulations Act which has enabled MFIs to mobilize further public deposits and savings. According to BOZ out of 25 licensed institutions have been granted deposit taking licenses. More importantly, the Act has established governance rules and formal accountability channels with the central bank, so that MFIs might evolve into limited companies with identifiable share holders (AMIZ magazine, June 2010). However, there is as yet little serious empirical study of Zambian microfinance, where institutional performance data is still considered proprietary, and remains difficult to access Micro Finance. Enhanced disclosure might reveal more but, so far, the few impact studies have concentrated upon CETZAM (Cheston, et al., 2000; Copestake et al. 2001; Copestake, 2002), except for Copestake, Bhalotra and

Johnsons (1998) study of the Peri-Urban Lusaka Small Enterprise (PULSE). No similar impact studies have been conducted on Micro Finance institutions. METHODOLOGY Study Design The study will use both the qualitative and quantitative designs in which will use graphical presentation of observed phenomena order to give accurate information on the impact of micro finance institutions in women empowerment in Kabwe, Zambia. The process will depict the prevailing situation using random sampling method. Sample size

The sample size will comprise of 50 respondents that will comprise of 40 Women running micro finance businesses, FINCA field Officers and Management members.

Target Population The research intends to cover Women who will be currently beneficiaries of FINCA Loans, FINCA Field Officers and Staff members in Kabwe, Zambia. Data Collection Both primary and secondary data will be used in collecting information.

Data Collection Instruments

Interview Guide This will cover a wide range of questions on women empowerment and micro Finance. It will be designed and administered to those who will be willing to be interviewed at their own convenient time.

Questionnaires It will be used in data collection where it will not be possible to meet all the respondents at one point. Sampling Procedures

The simple random sampling procedures will be used in this research for its high degree of representatives. In this

particular case, a rotary method of sampling wills applies. In an attempt to choose 40 women from different groups without bias.

Data Analysis Analysis of data will be done by using graphs, bar charts and pie charts showing responses from participants. References Basu, A., Blavy, R.,&Yulek, M. (2004). Microfinance in Africa: Experience and lessons from selected African Countries. IMF Working Paper. African Department, WP/04/174. CGAP Brief, December 2009. The Rise, Fall, and Recovery of the Microfinance Sector in Morocco

Chiumya C, (2006) The Regulation of Microfinance Institutions: A Zambian Case Study, University of Manchester, Unpublished PhD Copestake, J. (2002). Inequality and the polarizing impact of microcredit: Evidence from Zambias Copperbelt. Journal of International Development, 14(6), 743755. Copestake, J., Bhalotra, S., & Johnson, S. (2001). Assessing the impact of microfinance: A Zambian case study, Journal of Development Studies, 37(4), 81100. Dixon, R., Ritchie, J. and Siwale J. (2007) Loan officers and loan delinquency in microfinance: A Zambian case, Accounting Forum 31:47-71. Dixon, R., Ritchie, J. and Siwale, J. (2006) Microfinance: Accountability from the grassroots, Accounting, Auditing and Accountability Journal 19 (3): 405-427. Eisenhardt, K. (1989), Building theories from case study research, Academy of Management Review, Vol. 14 No.4, pp. 532-50. Fisher, T. (2002). Emerging lessons and challenges. In T. Fisher & M. S. Scriam (Eds.), Beyond micro-credit: Putting

development back into micro-finance (pp. 325360). New Delhi: Vistaar publication.

Hartaska, V. (2005) Governance and Performance of Microfinance Institutions in Central and Eastern Europe and the Newly Independent States World Development, Vol. 33, No.10, pp. 1627-1643 Labie, M. (2001). Corporate governance in microfinance organizations: a long and winding road. Management Decision 39 (4), 296 -301 Lafourcade, A. L., Isern, J., Mwangi, P., & Brown, M. (2005). Overview of the outreach and financial performance of microfinance institutions in Africa. MicroBanking Bulletin, Issue, 11. Law, John (2004). After Method: Mess in Social Science Research. London, Routledge McGahan, A.M. and Porter, M.E. (1997). How much does industry matter, really? Strategic Management Journal, 18, 15-30

Mellahi, K (2005) The dynamics of Boards of Directors in Failing Organizations Long Range Planning (38): 261-279 Mellahi, K and Wilkinson, A (2010) Managing and Coping with Organizational Failure: Introduction to the Special Issue Group and Organization Management, 35 (5) 531-541 Mellahi, K., and Wilkinson, A. (2004). Organizational failure: A critique of recent research and a proposed integrative framework. International Journal of Management Reviews, 5/6 (1), 21-41 Mersland, R and Strom, R (2009) Performance and governance in microfinance institutions Journal of Banking and Finance 33, pp662-669 Mersland, R and Strom,R. (2009) Performance and governance in microfinance institutions, Journal of Banking and Finance 33: 662-669. Mukama, J., Fish T., and Volschenk, J. (2005) Problems Affecting the Growth of Microfinance Institutions in Tanzania. The African Finance Journal Vol. 7, part 2:42-63. Power, M. (2007). Organized Uncertainty: Designing a world of risk management. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Pugliese, G,M. (2010). Same game, different league? What microfinance institutions can learn from the large banks corporate governance debate Geneva Papers on inclusiveness No. 11, October, 2010. PRIDE Zambias Narrative Report (-04-Aug-1009-Mar-05) to SIDA (2004) Rumelt, R.P. (1991). How much does industry matter? Strategic Management Journal, 12, 167-185 Siwale, J. (2006). The role of loan officers and clients in the diffusion of microfinance: A study of PRIDE Zambia and CETZAM in Zambia. University of Durham: Unpublished Ph.D. Thesis. Spencer, S., & Wood, A. (2005) Making the financial sector work for the poor. Journal of Development Studies, 41(4), 657675. Tedlow, R.S. (2008). Leaders in denial. Harvard Business Review, 86 (7/8), 18-19 Vaughan, D. (1996), The Challenger Launch Decision. Chicago: University of Chicago Press

World Bank (2009). World Washington, DC: World Bank

Development

Report.

Yin, R.K. (2003). Case Study Research: Design and Methods (3rd Ed.). Sage publication APPENDIX SECTION Am a student at the Womens University in Africa, Harare, Zimbabwe doing my final year project. I am conducting a study in Kabwe on the impact of micro finance institutions on women empowerment in Kabwe, Zambia. You have been randomly selected to answer a few questions on this topic. Be assured that all responses given will be treated with utmost confidentiality and privacy. This exercise is purely for academic purposes.

Você também pode gostar

- Impact of Microfinance To Empower Female EntrepreneursDocumento6 páginasImpact of Microfinance To Empower Female EntrepreneursInternational Journal of Business Marketing and ManagementAinda não há avaliações

- Research Proposal: Impact of Micro Finance Institutions On Women Empowerment in Zambia by Mutale Tricia BwalyaDocumento19 páginasResearch Proposal: Impact of Micro Finance Institutions On Women Empowerment in Zambia by Mutale Tricia BwalyaUtkarsh MishraAinda não há avaliações

- Asia Small and Medium-Sized Enterprise Monitor 2020: Volume I: Country and Regional ReviewsNo EverandAsia Small and Medium-Sized Enterprise Monitor 2020: Volume I: Country and Regional ReviewsAinda não há avaliações

- Microfinance in GhanaDocumento5 páginasMicrofinance in Ghanarexford100% (11)

- Shg-Self Help GroupDocumento56 páginasShg-Self Help Groupkaivalya chaaitanya ugale100% (2)

- Report On MicrofinanceDocumento79 páginasReport On MicrofinanceParmarth Varun67% (3)

- Research ProposalDocumento9 páginasResearch ProposalImpassible SunAinda não há avaliações

- SHG Training ManualDocumento95 páginasSHG Training ManualZareenAinda não há avaliações

- 8.chapter II Review - of - LiteratureDocumento51 páginas8.chapter II Review - of - Literaturesowmiya Sankar100% (1)

- Women EntrepreneursDocumento99 páginasWomen EntrepreneursAisha Akram92% (36)

- Promotion of Women Empowerment and Rights (POWER) Project Proposal by Mutual Relief and Liberty OrganizationDocumento11 páginasPromotion of Women Empowerment and Rights (POWER) Project Proposal by Mutual Relief and Liberty OrganizationमनिसभेटुवालAinda não há avaliações

- Financial Literacy Survey - Sri Lanka 2021Documento18 páginasFinancial Literacy Survey - Sri Lanka 2021Adaderana OnlineAinda não há avaliações

- Case Studies of Women Entrepreneurs in Service Sector in Chennai CityDocumento17 páginasCase Studies of Women Entrepreneurs in Service Sector in Chennai CityarcherselevatorsAinda não há avaliações

- 1.overview: Project Title: Youth For Change InitiaveDocumento8 páginas1.overview: Project Title: Youth For Change InitiaveVedaste NdayishimiyeAinda não há avaliações

- USAID Support For NGO Building - Approaches, Examples, MechanismsDocumento45 páginasUSAID Support For NGO Building - Approaches, Examples, MechanismsAisha SiddiqueAinda não há avaliações

- Women Empowerment Throuh Selfhelp GroupsDocumento17 páginasWomen Empowerment Throuh Selfhelp Groupspradeep324Ainda não há avaliações

- Women Entrepreneurship in India Research ProjectDocumento24 páginasWomen Entrepreneurship in India Research ProjectDevesh RajakAinda não há avaliações

- Rual Primary School Project ProposalDocumento7 páginasRual Primary School Project ProposalAmmutha Sokayah100% (2)

- Project Work On Rural Development of The NagasDocumento16 páginasProject Work On Rural Development of The NagasHukuyi Venuh100% (1)

- Ngo List in BiharDocumento7 páginasNgo List in Biharrks81Ainda não há avaliações

- Success in Business.Documento26 páginasSuccess in Business.Lamyae ez- zghari100% (1)

- Challenges Faced by Indian EntrepreneursDocumento36 páginasChallenges Faced by Indian EntrepreneursPrashu171091Ainda não há avaliações

- PrefaceDocumento4 páginasPrefaceAnkur ChopraAinda não há avaliações

- Background of The OrganizationDocumento32 páginasBackground of The OrganizationZiko RahmanAinda não há avaliações

- Women EmpowermentDocumento7 páginasWomen EmpowermentJessica Glenn100% (1)

- Challenges of NgosDocumento8 páginasChallenges of NgosNishan KhanAinda não há avaliações

- Entrepreneurship in India Scenario-Vol2no1 - 6 PDFDocumento5 páginasEntrepreneurship in India Scenario-Vol2no1 - 6 PDFMahibul IslamAinda não há avaliações

- Strengths:: The Swot AnalysisDocumento1 páginaStrengths:: The Swot AnalysisPhool Kumar JhaAinda não há avaliações

- Project Proposal On Self EmployabilityDocumento24 páginasProject Proposal On Self EmployabilityMaria Melanie Maningas Montiano-LotoAinda não há avaliações

- Research Proposal: A Study On Capital Productivity of Small & Medium Scale Industries in KarnatakaDocumento6 páginasResearch Proposal: A Study On Capital Productivity of Small & Medium Scale Industries in Karnatakashashikiranl858050% (2)

- Is Globalization A Ver Necessary EvilDocumento6 páginasIs Globalization A Ver Necessary EvilhhgfAinda não há avaliações

- AssignmentDocumento16 páginasAssignmentPrincy JohnAinda não há avaliações

- ProposalDocumento21 páginasProposalPrincy JohnAinda não há avaliações

- Literature Review On MicrofinanceDocumento8 páginasLiterature Review On Microfinancenivi_nandu362833% (3)

- Concept Note On Livelihood Enhancement of Poor in South Odisha: by Harsha TrustDocumento12 páginasConcept Note On Livelihood Enhancement of Poor in South Odisha: by Harsha TrustAlok Kumar Biswal100% (1)

- 1606 Impact of Financial Literacy OnDocumento19 páginas1606 Impact of Financial Literacy OnfentahunAinda não há avaliações

- Fdi in Nigeria ThesisDocumento62 páginasFdi in Nigeria ThesisYUSUF BAKO100% (1)

- Micro Finance & Women EmpowermentDocumento32 páginasMicro Finance & Women EmpowermentMegha Solanki67% (3)

- SWOT of Self Help GroupDocumento17 páginasSWOT of Self Help GroupAnand Jha0% (1)

- Micro Finance Complete Project VijayDocumento66 páginasMicro Finance Complete Project Vijaynaveemraja100% (4)

- Report On Micro FinanceDocumento55 páginasReport On Micro Financearvind.vns14395% (73)

- Concept Note - Integrated FarmingDocumento6 páginasConcept Note - Integrated Farmingsunthar82Ainda não há avaliações

- 1 1 MFI Survey QuestionnaireDocumento26 páginas1 1 MFI Survey QuestionnaireAbhishek Singh75% (4)

- Research ProposalDocumento34 páginasResearch ProposalSimon Muteke100% (1)

- Youth Empowerment and Livelihoods...Documento122 páginasYouth Empowerment and Livelihoods...Muchiri E Maina100% (1)

- Sustainable Development in IndiaDocumento17 páginasSustainable Development in IndiaAnil BatraAinda não há avaliações

- Social Project-Dec 2017Documento36 páginasSocial Project-Dec 2017Dilzz KalyaniAinda não há avaliações

- Sustainable Tourism Research ProjectDocumento82 páginasSustainable Tourism Research ProjectravindrahawkAinda não há avaliações

- Camp ProposalDocumento16 páginasCamp Proposalngeshb0% (1)

- Microfinance in IndiaDocumento12 páginasMicrofinance in IndiaRavi KiranAinda não há avaliações

- Self Help GroupsDocumento13 páginasSelf Help GroupsSomya AggarwalAinda não há avaliações

- Finacial LiterncyDocumento48 páginasFinacial LiterncyKiranAinda não há avaliações

- Homestay Tourism in BDDocumento5 páginasHomestay Tourism in BDSazib Shohidul Islam100% (1)

- Attracting Youth in Agriculture in Asia Final PaperDocumento45 páginasAttracting Youth in Agriculture in Asia Final PaperKendy Marr Salvador100% (1)

- Empowerment of Women Through MicrofinanceDocumento22 páginasEmpowerment of Women Through MicrofinanceKevin Jacob100% (2)

- Introduction To S.R.PDocumento12 páginasIntroduction To S.R.PPrabhdeep ChhabraAinda não há avaliações

- Heinrich Research ProposalDocumento18 páginasHeinrich Research ProposalJustin Alinafe MangulamaAinda não há avaliações

- Introduction - Single FileDocumento8 páginasIntroduction - Single FileranjithAinda não há avaliações

- Microfinance and Women EntrepreneurshipDocumento8 páginasMicrofinance and Women EntrepreneurshipMEERA RAVI PSGRKCWAinda não há avaliações

- S 11 - Capital Budgeting For The Levered FirmDocumento13 páginasS 11 - Capital Budgeting For The Levered FirmAninda DuttaAinda não há avaliações

- Kotak Mahindra Bank Limited Standalone Financials FY18Documento72 páginasKotak Mahindra Bank Limited Standalone Financials FY18Shankar ShridharAinda não há avaliações

- Individual Assignment 1Documento2 páginasIndividual Assignment 1Getiye LibayAinda não há avaliações

- RSIretDocumento4 páginasRSIretPrasanna Pharaoh100% (1)

- Peak Performance Forex TradingDocumento183 páginasPeak Performance Forex TradingK. Wendy Ozzz100% (2)

- Service Tax NotesDocumento24 páginasService Tax Notesfaraznaqvi100% (1)

- Charge BackDocumento9 páginasCharge Backسرفراز احمدAinda não há avaliações

- Variable Production Overhead Variance (VPOH)Documento9 páginasVariable Production Overhead Variance (VPOH)Wee Han ChiangAinda não há avaliações

- 10 Administrative DecentralisationDocumento16 páginas10 Administrative DecentralisationAlia Al ZghoulAinda não há avaliações

- Hoisington Q3Documento6 páginasHoisington Q3ZerohedgeAinda não há avaliações

- Corporation Law - Case DigestsDocumento7 páginasCorporation Law - Case DigestsFrancis Dominick AbrilAinda não há avaliações

- 9 CNG Cost Components PDFDocumento9 páginas9 CNG Cost Components PDFReno SaibihAinda não há avaliações

- Key Factors Weight AS TASDocumento5 páginasKey Factors Weight AS TASasdfghjklAinda não há avaliações

- AS310 Midterm Test Sep Dec2021 PDFDocumento1 páginaAS310 Midterm Test Sep Dec2021 PDFGhetu MbiseAinda não há avaliações

- AVT Natural Products-R-26032018 PDFDocumento7 páginasAVT Natural Products-R-26032018 PDFBoss BabyAinda não há avaliações

- Sn53sup 20170430 001 2200147134Documento2 páginasSn53sup 20170430 001 2200147134Henry LowAinda não há avaliações

- Foundation Forum: College and Career Center Tops The Priority ListDocumento4 páginasFoundation Forum: College and Career Center Tops The Priority ListnsidneyAinda não há avaliações

- Leases Part IIDocumento21 páginasLeases Part IICarl Adrian ValdezAinda não há avaliações

- Admin Law Cases Week 3Documento18 páginasAdmin Law Cases Week 3bidanAinda não há avaliações

- Bisi 2018Documento96 páginasBisi 2018Akun NuyulAinda não há avaliações

- Check List LOANDocumento12 páginasCheck List LOANshushanAinda não há avaliações

- KSPI FY24 Guidance For 2024Q2Documento8 páginasKSPI FY24 Guidance For 2024Q2brianlam205Ainda não há avaliações

- Identifying Text Structure #1Documento3 páginasIdentifying Text Structure #1Ethiopia FurnAinda não há avaliações

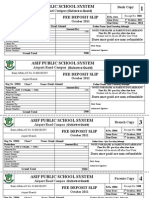

- Asif Public School System: Fee Deposit SlipDocumento1 páginaAsif Public School System: Fee Deposit SlipIrfan YousafAinda não há avaliações

- Commitment LetterDocumento306 páginasCommitment LetterNoor Azah AdamAinda não há avaliações

- SwiggyDocumento9 páginasSwiggyEsha PandyaAinda não há avaliações

- Portfolio Strategy Asia Pacific: The Goldman Sachs Group, IncDocumento20 páginasPortfolio Strategy Asia Pacific: The Goldman Sachs Group, IncNivasAinda não há avaliações

- 4 Managing Debts Effectively PDFDocumento48 páginas4 Managing Debts Effectively PDFLawrence CezarAinda não há avaliações

- Inventory Lecture NotesDocumento15 páginasInventory Lecture NotessibivjohnAinda não há avaliações

- Bar Questions - Obligations and ContractsDocumento6 páginasBar Questions - Obligations and ContractsPriscilla Dawn100% (9)