Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

Little Coherence, Considerable Strain For Reader, A Comparison Between Two Rating Scales For The Assessment of Coherence

Enviado por

NaniTítulo original

Direitos autorais

Formatos disponíveis

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Little Coherence, Considerable Strain For Reader, A Comparison Between Two Rating Scales For The Assessment of Coherence

Enviado por

NaniDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Available online at www.sciencedirect.

com

Assessing Writing 12 (2007) 108128

Little coherence, considerable strain for reader: A comparison between two rating scales for the assessment of coherence

Ute Knoch

Language Testing Research Centre, University of Melbourne, Level 3, 245 Cardigan Street, Carlton, Victoria 3052, Australia Available online 17 October 2007

Abstract The category of coherence in rating scales has often been criticized for being vague. Typical descriptors might describe students writing as having a clear progression of ideas or lacking logical sequencing. These descriptors inevitably require subjective interpretation on the side of the raters. A number of researchers (Connor & Farmer, 1990; Intaraprawat & Steffensen, 1995) have attempted to measure coherence more objectively. However, these efforts have not thus far been reected in rating scale descriptors. For the purpose of this study, the results of an adaptation of topical structure analysis (Connor and Farmer, 1990; Schneider and Connor, 1990), which proved successful in distinguishing different degrees of coherence in 602 academic writing scripts was used to formulate a new rating scale. The study investigates whether such an empirically grounded scale can be used to assess coherence in students writing more reliably and with greater discrimination than the more traditional measure. The validation process involves a multi-faceted Rasch analysis of scores derived from multiple ratings of 100 scripts using the old and new rating descriptors as well as a qualitative analysis of questionnaires canvassed from the raters. The ndings are discussed in terms of their implications for rating scale development. 2007 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.

Keywords: Writing assessment; Rating scales; Coherence; Rating scale validation; Multi-faceted Rasch analysis

1. Introduction Because writing assessment requires subjective evaluations of writing quality by raters, the raw score candidates receive might not reect their actual writing ability. In an attempt to reduce the

Tel.: +61 3 83445206; fax: +61 3 83445163. E-mail address: uknoch@unimelb.edu.au.

1075-2935/$ see front matter 2007 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved. doi:10.1016/j.asw.2007.07.002

U. Knoch / Assessing Writing 12 (2007) 108128

109

variability between raters and therefore to increase the reliability of ratings, attempts have been made to improve certain features of the rating process, most commonly through rater training (Elder, Knoch, Barkhuizen, & von Randow, 2005; McIntyre, 1993; Weigle, 1994a, 1994b, 1998). However, despite all the efforts put into training raters, it has been shown that differences in rater reliability persist and can account for as much as 35% of variance in students written performance (Cason & Cason, 1984). Some researchers have suggested that a better specication of scoring criteria might lead to an increase in rater reliability (Hamp-Lyons, 1991; North, 1995, 2003; North & Schneider, 1998). One reason for the variability found in writing performance might lie in the way rating scales are designed. Fulcher (2003) has shown that most existing rating scales are developed based on intuitive methods which means that they are either adapted from already existing scales or they are based on what developers think might be common features in the writing samples in question. However, for rating scales to be more valid, it has been contended that rating scales should be based on empirical investigation of actual writing samples (North & Schneider, 1998; Turner & Upshur, 2002; Upshur & Turner, 1995, 1999). 2. The assessment of coherence in writing Lee (2002) denes coherence as the relationships that link the ideas in a text to create meaning. Although a number of attempts have been undertaken in second language writing research to operationalize coherence (Cheng & Steffensen, 1996; Connor & Farmer, 1990; Crismore, Markkanen, & Steffensen, 1993; Intaraprawat & Steffensen, 1995), this has not been reected in rating scales commonly used in the assessment of writing. Watson Todd, Thienpermpool and Keyuravong (2004), for example, criticized the level descriptors for coherence in a number of rating scales as being vague and lacking enough detail for raters to base their decisions on. They quote a number of rating scale descriptors used for measuring coherence. The commonly used and much cited Jacobs scale (Jacobs, Zinkgraf, Wormuth, Hartel, & Hughey, 1981), for example, describes high quality writing as well organized and exhibiting logical sequencing. In other scales less successful writing has been described for example as being fragmentary so that comprehension of the intended communication is virtually impossible (TEEP Attribute Writing Scales, cited in Watson Todd et al., 2004). Watson Todd et al. therefore argue that while analytic criteria are intended to increase the reliability of rating, the descriptors quoted above inevitably require subjective interpretations of the raters and might lead to confusion. Although one reason for these vague descriptions of coherence might lie in the rather vague nature of coherence, Hoey (1991) was able to show that judges are able to reach consensus on the level of coherence. A notable exception to the scales described above is a scale for coherence developed by Bamberg (1984). Although Bamberg was able to develop more explicit descriptors for a number of different aspects of writing related to coherence (e.g., organization and topic development), her holistic scale descriptors mix a variety of aspects at the descriptor level. The descriptor for level 2, for example, describes the writing as incoherent, refers to topic identication, setting of context, the use of cohesive devices, the absence of an appropriate conclusion, ow of discourse and errors. Although the scale has ve levels, when Bambergs raters used the scale, they seemed to only be able to identify three levels. It is possible that because this holistic scale mixes so many aspects at the descriptor level, raters were overusing the inner three band levels of the scale and avoiding the extreme levels. It seems that no existing rating scale for coherence has been able to operationalize this aspect of writing in a manner that can be successfully used by raters. The aim of this study was therefore to attempt to develop a rating scale for coherence which is empirically-based.

110

U. Knoch / Assessing Writing 12 (2007) 108128

2.1. Topical structure analysis (TSA) In the second language writing literature, several attempts have been made to measure coherence. To be transferable into a rating scale, the method chosen for this study needs to be sufciently simple to be used by raters who are rating a number of scripts in a limited amount of time. Several methods were investigated as part of the literature review for this study. Crismore et al.s (1993) metadiscoursal markers were excluded because insufcient tokens were found in students essays and measures like topic-based analysis (Watson Todd, 1998; Watson Todd et al., 2004) needed to be excluded for being too complicated and time consuming. For this study, topical structure analysis (TSA) was chosen and adapted because it was the only attempt at operationalizing coherence which was sufciently simple to be transferred into a rating scale. TSA, based on topic and comment analysis, was rst described by Lautamatti (1987) from the Prague School of Linguistics in the context of text readability to analyze topic development in reading material. She dened the topic of a sentence as what the sentence is about and the comment of a sentence as what is said about the theme. Lautamatti described three types of progression, which create coherence in a text. These types of progression advance the discourse topic by developing a sequence of sentence topics. Through this sequence of sentence topic, local coherence is created. The three types of progression can be summarized as follows (Hoenisch, 1996): 1. Parallel progression, in which topics of successive sentences are the same, producing a repetition of topic that reinforces the idea for the reader (<a, b>, <a, c>, <a, d>). Example: Paul walked on the street. He was carrying a backpack. 2. Sequential progression, in which topics of successive sentences are always different, as the comment of one sentence becomes, or is used to derive, the topic of the next (<a, b>, <b, c>, <c, d>). Example: Paul walked on the street. The street was crowded. 3. Extended parallel progression, in which the rst and the last topics of a piece of text are the same but are interrupted with some sequential progression (<a, b>, <b, c>, <a, d>). Example: Paul walked on the street. Many people were out celebrating the public holiday. He had trouble nding his friends. Witte (1983a, 1983b) introduced TSA into writing research. He compared two groups of persuasive writing scripts, one rated high and one rated low, on the use of the three types of progression described above. He found that the higher level writers used less sequential progression, and more extended and parallel progression. There were, however, several shortcomings of Wittes study. Firstly, the raters were not professional raters, but rather were solicited from a variety of professions. Secondly, Witte did not use a standardized scoring scheme. He also conducted the study in a controlled revision situation in which the students revised a text written by another person. Furthermore, Witte did not report any intercoder reliability analysis. In 1990, Schneider and Connor set out to compare the use of topical structures by 45 writers taking the Test of Written English (TWE). They grouped the 45 argumentative essays into three different levels: high, medium, low. As with Wittes study, Schneider and Connor did not report any intercoder reliability statistics. The ndings were contradictory to Wittes ndings: the higher level writers used more sequential progression while the low and middle group used more parallel progression. There was no difference between the levels in the use of extended parallel progression. Schneider and Connor drew up clear guidelines on how to code TSA and also suggested

U. Knoch / Assessing Writing 12 (2007) 108128

111

a reinterpretation of sequential progression as part of their discussion section. They suggested dividing sequential progression into the following subcategories: 1. Direct sequential progression, in which the comment of the previous sentence becomes the topic of the following sentence. The topic and comment are either word derivations (e.g., science, scientist) or they form a part-whole relation (these groups, housewives, children) (<a, b>, <b, c>, <c, d>). 2. Indirect sequential progression, in which the comment of the previous sentence becomes the topic of the following sentence but topic and comment are only related by semantic sets (e.g., scientists, their inventions and discoveries, the invention of the radio, telephone and television). 3. Unrelated sequential progression, in which topics are not clearly related to either the previous sentence topic or discourse topic (<a, b>, <c, d>, <e, f>). Wu (1997), in his doctoral dissertation, applied Schneider and Connors revised categories to analyze two groups of scripts rated using the scale developed by Jacobs et al. (1981). He found in his analysis no statistically signicant difference in terms of the use of parallel progression between high and low level writers. Higher level writers used slightly more extended parallel progression and more direct sequential progression.A more recent study using TSA to compare groups of writing based on holistic ratings, was undertaken by Burneikait and Zabili t (2003). Using the e ue original criteria of topical structure developed by Lautamatti and Witte, they investigated the use of topical structure in argumentative essays by three groups of students rated as high, middle and low based on a rating scale adapted from Tribble (1996). They found that the lower level writers over-used parallel progression whilst the higher level writers used a balance between parallel and extended parallel progression. The differences in terms of sequential progression were small, although they could show that lower level writers use this type of progression slightly less regularly. Burneikait and Zabili t failed to report any interrater reliability statistics. e ue All studies conducted since Wittes study in 1983 show generally very similar ndings, however there are slight differences. Two out of three studies found that lower level writers used more parallel progression than higher level writers; however, Wu (1997) found no signicant difference. All three studies found that higher level writers used more extended parallel progression. In terms of sequential progression the differences in ndings can be explained by the different ways this category was used. Schneider and Connor (1990), and Burneikait and Zabili t (2003) used the e ue denition of sequential progression with no subcategories. Both studies found that higher level writers used more sequential progression. Wu (1997) found no differences between different levels of writing using this same category. However, he was able to show that higher level writers used more related sequential progression. It is also not entirely clear how much task type or topic familiarity inuences the use of topical structure and if ndings can be transferred from one writing situation to another. 3. The study The aim of this study was to investigate whether TSA can successfully be operationalized into a rating scale to assess coherence in writing. The study was undertaken in three phases. Firstly, 602 writing samples were analyzed to establish the topical structure used by writers at ve levels of writing ability. The ndings were then transferred into a rating scale. To validate this scale, eight raters were trained and then rated 100 writing samples. The ndings were compared to previous ratings of the same 100 scripts by the same raters using an existing rating scale for coherence.

112

U. Knoch / Assessing Writing 12 (2007) 108128

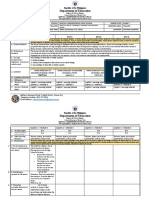

Fig. 1. Research design.

After the rating rounds, raters were given a questionnaire to ll in to canvass their opinions about the rating scale and a subset of ve raters was interviewed. Fig. 1 illustrates the design of the study visually. The research questions were as follows: RQ1: What are the features of topical structure displayed at different levels of expository writing? RQ2: How reliable and valid is TSA when used to assess coherence in expository writing? RQ3: What are raters perceptions of using TSA in a rating scale as compared to more conventional rating scales? 4. Method 4.1. Context of the research This study was conducted in the context of the Diagnostic English Language Needs Assessment (DELNA) which is administered at the University of Auckland, New Zealand. DELNA is a university-funded procedure designed to identify the English language needs of undergraduate students following their admission to the University, so that the most appropriate language support can be offered. DELNA is administered to both native and non-native speakers of English. This context was selected by the researcher purely because of its availability and because the rating scale used to assess the writing task (see description below) is representative of many other rating scales used in writing performance assessment across the world. A more detailed description of the assessment and the rating scale can be found in the section below. 4.1.1. The assessment instrument DELNA includes a screening component which consists of a speed-reading and a vocabulary task. This is used to eliminate highly procient users of English and exempts them from the timeconsuming and resource-intensive diagnostic procedure. The diagnostic component comprises objectively scored reading and listening tasks and a subjectively scored writing task. The writing section is an expository writing task in which students are given a table or graph of information which they are asked to describe and interpret. Candidates have 30 minutes to complete the task. The writing task is routinely double (or if necessary triple) marked analytically on nine traits (organization, coherence, style, data description, interpretation, development of ideas, sentence structure, grammatical accuracy, vocabulary and spelling) on a six-point scale ranging from four to nine. The assessment criteria were developed in-house, initially based on an existing scale. A number of validity studies have been conducted on the DELNA battery, which included validation of the rating scale (Elder & Erlam, 2001; Elder & von Randow, 2002). The wording of the scale has been changed a number of times based on the feedback of raters after

U. Knoch / Assessing Writing 12 (2007) 108128

113

training sessions or during focus groups. The DELNA rating scale reects common practice in performance assessment in that the descriptors are graded using adverbs like adequate, appropriate, sufcient, severe or slight. The coherence scale uses descriptors like skilful coherence, message able to be followed effortlessly or little coherence, considerable strain for reader. Strain is graded between different level descriptors from slight, some, considerable to severe. 4.1.2. The writing samples To identify the specic features of topical structure used by writers taking DELNA, 602 writing samples, which were produced as part of the 2004 administration of the assessment, were randomly selected. The samples were originally hand-written by the candidates. The mean number of words for the scripts was 269, ranging from 75 to 613. 4.1.3. The candidates Three hundred twenty-nine of the writing samples were produced by females and 247 by males (roughly reecting the gender distribution of DELNA), whilst 26 writers did not specify their gender. The L1 of the students (as reported in a self-report questionnaire) varied. Forty-two percent (or 248 students, N = 591) have an Asian rst language, 36% (217) are native speakers of English, 9% (52) are speakers of a European language other than English, 5% (31) have either a Pacic Island language or Maori as rst language, and 4% (21) speak either an Indian or a language from Sri Lanka as rst language. The remaining 4% (22) were grouped as others. Eleven students did not ll in the self-report questionnaire. The scripts used in this analysis were all rated by two DELNA raters. In case of discrepancies between the scores, the scores were averaged and rounded (in the case of a .5 result after averaging, the score was rounded down). The 602 scripts were awarded the following average marks (Table 1). 4.1.4. The raters The eight DELNA raters taking part in this study were drawn from a larger pool of raters based on their availability at the time of the study. All raters have high levels of English prociency although not all are native speakers of English. Most have experience in other rating contexts, for example, as accredited raters of the International English Language Testing System (IELTS). All have postgraduate degrees in either English, Applied Linguistics or Teaching English to Speakers of other Languages (TESOL). All raters have several years of experience as DELNA raters and take part in regular training moderation sessions either in face-to-face or online sessions (Elder, Barkhuizen, Knoch, & von Randow, 2007; Knoch, Read, & von Randow, 2007).

Table 1 Score distribution of 602 writing samples DELNA score 4 5 6 7 8 Frequency 23 115 253 172 26 Percent (%) 4 19 46 29 4

114

U. Knoch / Assessing Writing 12 (2007) 108128

4.2. Proceduresanalysis of writing samples 4.2.1. Pilot study While coding the 602 writing scripts, the categories of parallel, direct sequential and unrelated sequential progression were used as dened by Schneider and Connor (1990) and Wu (1997). However, other categories had to be changed or added to better account for the data. Firstly, extended parallel progression was changed to extended progression to account for cases in which the topic of a sentence is identical to a comment occurring more than two sentences earlier. Similarly, indirect sequential progression was modied to indirect progression to also include cases in which the indirect link is back to the previous topic. Then, a category was created that accounts for features very specic to writers whose L1 is not English. At very low levels, these writers often attempt to create a coherent link back to the previous sentence but fail because, for example, they use an incorrect linking device or a false pronominal. This category was called coherence break. Another category was established to account for coherence that is created not by topic progression but by features such as linking devices (e.g., however, also, but). This category also includes cases in which the writer clearly signals the ordering of an essay or paragraph early on, so that the writer can follow any piece of discourse without needing topic progression as guidance. Table 2 below presents all categories of topical structure used in the main analysis with denitions and examples.1 4.2.2. Main analysis To analyze the data, the writing scripts were rst typed and then divided into t-units following Schneider and Connor (1990) and Wu (1997). The next step was to identify sentence topics. For this, Wus (1997) criteria were used (see Appendix A). Then each t-unit was coded into one of the seven categories as described in Table 2. The percentage of each category was recorded into a spreadsheet. The mean DELNA score produced by the two DELNA raters was also added for each candidate. To identify which categories were used by students at different prociency levels, the nal score was correlated with the percentage of occurrence of each category. The results of this analysis can be found in the results section under research question 1 below. Finally, to ensure intercoder reliability, t-unit coding, topic identication and TSA were all undertaken by a second researcher (on a subset of 50 scripts) and intercoder reliability was calculated. 4.3. Proceduresrating scale validation 4.3.1. Procedure The raters rated 100 scripts using the current DELNA criteria and then the same 100 using the new scale based on TSA. The scripts were selected to represent a range of prociency levels. The raters were given the scripts in ve sets of 20 scripts over a time period of about eight weeks. They all participated in a rater moderation session to ensure they were thoroughly trained. All raters were further instructed to rate no more than ten scripts in one session to avoid fatigue. After rating the two sets of 100 scripts, the raters lled in a questionnaire canvassing their opinions about the scales. The questionnaire (part of a larger-scale study) allowed the raters to record any opinions or suggestions they had with respect to the coherence scale. The questionnaire questions were as follows:

All examples were taken from the data used in this study.

U. Knoch / Assessing Writing 12 (2007) 108128 Table 2 Categories of topical structure analysis used in main analysis with examples Parallel progression Topics of successive sentences are the same (or synonyms) <a,b> <a,c> Maori and PI males are just as active as the rest of NZ. They also have other interests Direct sequential progression The comment of the previous sentence becomes the topic of the following sentence <a,b> <b,c> The graph showing the average minutes per week spent on hobbies and games by age group and sex, shows many differences in the time spent by females and males in NZ on hobbies and games These differences include on age factor Indirect progression The topic or the comment of the previous sentence becomes the topic of the following sentence. The topic/or comment are only indirectly related (by inference, e.g., related semantic sets) <a,b> <indirect a, c> or <a,b> <indirect b, c> The main reasons for the increase in the number of immigrates is the development of some third-world countries. e.g., China. People in those countries have got that amount of money to support themselves living in a foreign country Superstructure Coherence is created by a linking device instead of topic progression <a,b> <linking device, c,d> Reasons may be the advance in transportation and the promotion of New Zealands natural environment and green image. For example, the lming of The Lord of the rings brought more tourists to explore the beautiful nature of NZ Extended progression A topic or a comment before the previous sentence become the topic of the new sentence <a,b> ... <a,c> or <a,b> ... <b,c> The rst line graph shows New Zealanders arriving in and departing from New Zealand between 2000 and 2002. The horizontal axis shows the times and the vertical axis shows the number of passengers which are New Zealanders. The number of New Zealanders leaving and arriving have increased slowly from 2000 to 2002. Coherence break Attempt at coherence fails because of an error <a,b> <failed attempts at a or b or linker, c> The reasons for the change on the graph. Its all depends on their personal attitude Unrelated progression Topic of a sentence is not related to the topic or comment in the previous sentence <a,b> <c,d> The increase in tourist arrivers has a direct affect to New Zealand economy in recent years. The government reveals that unemployment rate is down to 4% which is a great news to all New Zealanders

115

(1) What did you like about the scales? (2) Were there any descriptors that you found difcult to apply? If yes, please say why. (3) Please write specic comments that you have about the scales below. You could for example write how you used them, any problems that you encountered that you havent mentioned above or you can mention anything else you consider important. A subset of ve raters were also interviewed after the study was concluded.

116

U. Knoch / Assessing Writing 12 (2007) 108128

Table 3 TSA correlations with nal DELNA writing score Final writing score Parallel progression Direct sequential progression Superstructure Indirect progression Extended progression Unrelated progression Coherence break n = 602. a p < .01. .215a .292a .258a .220a .07 .202a .246a

4.3.2. Data analysis The results of the two rating rounds were analyzed using multi-faceted Rasch measurement in the form of the computer program FACETS (Linacre, 2006). FACETS is a generalization of Wright and Masters (1982) partial credit model that makes possible the analysis of data from assessments that have more than the traditional two facets associated with multiple-choice tests (i.e., items and examinees). In the many-facet Rasch model, each facet of the assessment situation (e.g., candidates, raters, trait) is represented by one parameter. The model states that the likelihood of a particular rating on a given rating scale from a particular rater for a particular student can be predicted mathematically from the prociency of the student and the severity of the rater. The advantages of using multi-faceted Rasch measurement is that it models all facets in the analysis onto a common logit scale, which is an interval scale. Because of this, it becomes possible to establish not only the relative difculty of items, ability of candidates and severity of raters as well as the scale step difculty, but also how large these differences are. Multi-faceted Rasch measurement is particularly useful in rating scale validation as it provides a number of useful measures such as rating scale discrimination, rater agreement and severity statistics and information with respect to the functioning of the different band levels in a scale. To make the multi-faceted Rasch analysis used in this study more powerful, a fully crossed design was chosen; that is, all eight raters rated the same 100 writing scripts on both occasions. Although such a fully crossed design is not necessary for FACETS to run the analysis, it makes the analysis more stable and therefore better conclusions can be drawn from the results (Myford & Wolfe, 2003). 5. Results 5.1. RQ1: What are the features of topical structure displayed at different levels of writing? The results of the intercoder reliability analysis show a high level of agreement for the two researchers coding the data. The proportion of exact agreement for the t-unit identication is .959, for the identication of the t-unit topics is .931 and for the TSA categories (as shown in Table 2) is .865. A Pearson correlation of the proportion that each TSA category was used in each essay with the overall writing score was performed in order to establish which categories are used at different levels of writing. The results of the correlation are reported in Table 3.

U. Knoch / Assessing Writing 12 (2007) 108128 Table 4 TSA-based rating scale for coherence Level 4 5 6 Coherence

117

Frequent: unrelated progression, coherence breaks Infrequent: sequential progression, superstructure, indirect progression As level 4, but coherence might be achieved in stretches of discourse by overusing parallel progression. Only some coherence breaks Mixture of most categories Superstructure relatively rare Few coherence breaks Frequent: sequential progression Superstructure occurring more frequently Infrequent: Parallel progression Possibly no coherence breaks Writer makes regular use of superstructures, sequential progression Few incidences of unrelated progression No coherence breaks

The table shows that the variables used for the analysis of TSA in the essays can be divided into three groups. The rst group consists of variables that were used more by students whose essays received a higher overall writing score. The three variables in this group are direct sequential progression, indirect progression, and superstructure. The second group is made up of variables that were used more by weaker writers. Variables in this group are coherence breaks, unrelated sequential progression, and parallel progression. The third group consists of variables that were used equally by the strong and the weak writers. The only variable that falls into this category is extended progression. The table showing the correlational results does not indicate the distribution over the different DELNA writing levels. Therefore, box plots were created for each variable, to indicate how the proportion of usage changes over the different DELNA band levels. The box plots can be found in Appendix B (Figs. 28). The box plots show that although there is a lot of overlap between the different levels of writing within each variable, there are clear trends in the distribution of the variables over the prociency levels. The only exception seems to be parallel progression, where writers at level 4 seemed to use fewer instances of parallel progression than writers at level 5. The quantitative results shown in the box plots were then used to develop the TSA-based rating scale. The trends for the different types of TSA categories observed in the box plots were used as the basis for the level descriptors. Because raters were presumably unable to identify small trends in the writing samples, general trends only were used for the different level descriptors. For example, raters were not asked to count each incident of each category of topical structure, rather they were guided as to what features they could expect least or most commonly at different levels. Because the strongest students were ltered out during the DELNA screening procedure, and therefore no scripts at band level 9 were analyzed, the TSA-based rating scale only has ve levels. However, the possibility of a sixth level exists. The scale is reproduced in Table 4. 5.2. RQ 2: How reliable and valid is TSA when used to assess coherence in writing? FACETS provides a group of statistics which investigates the spread of raters in terms of harshness and leniency (see Table 5). The rater xed chi square tests the assumption that all the raters share the same severity measure, after accounting for measurement error. A signicant

118 Table 5 Rater separation statistics

U. Knoch / Assessing Writing 12 (2007) 108128

DELNA scale Rater xed chi square value Rater separation ratio 66.9 d.f.: 7 signicance (probability): .00 2.94

TSA-based scale 216.8 d.f.: 7 signicance (probability): .00 5.62

Table 6 Rater int mean square values Rater 2 4 5 7 9 12 13 14 Mean S.D. Rater int mean square DELNA scale 1.11 1.30 1.53 .69 .91 1.08 .67 .69 1.00 .31 Rater point biserial DELNA scale .67 .54 .68 .68 .68 .50 .61 .65 .63 .07 Rater int mean square TSA-based scale 1.07 1.08 1.11 .98 .95 .97 .73 1.07 .99 .12 Rater point biserial TSA-based scale .65 .70 .79 .56 .65 .71 .70 .58 .67 .09

xed chi square means that the severity measures of at least two raters included in the analysis are signicantly different. The xed chi square value for both scales is signicant,2 showing that two or more raters are signicantly different in terms of leniency or harshness; however, the xed chi square value of the TSA-based scale is bigger indicating a larger difference between raters in terms of severity. The rater separation ratio provides an indication of the spread of the rater severity measures. The closer the separation ratio is to zero, the closer the raters are together in terms of their severity. Again, the larger separation ratio of the TSA-based scale shows that the raters differed more in terms of leniency and harshness. Another important output of the rater measurement report is the int mean square statistics with the rater point biserial correlations (see Table 6). The int mean square has an expected mean of 1. Raters with very low int mean square statistics (lower than .7) do not show enough variation in their ratings meaning they are overly consistent and possibly overuse the inner band levels of the scale, whilst raters with int mean square values higher than 1.3 show too much variation in their ratings meaning they rate inconsistently. Table 6 shows that two raters rated near the margins of acceptability when using the existing rating scale, whilst no raters rated too inconsistently when using the TSA-based scale. Three raters, however, showed not enough variation in their ratings when using the DELNA scale, shown by the int mean square values lower than .7. The rater point biserial correlation coefcient is reported for each rater individually as well as for the raters as a group. It summarizes the degree to which a particular raters ratings are consistent with the ratings of the rest of the raters. The point biserial correlation is concerned with

2 Myford and Wolfe (2004) note that the xed chi square test is very sensitive to sample size. Because of this, the xed chi square value is often signicant, even if the actual variation in terms of leniency and harshness between the raters is actually small.

U. Knoch / Assessing Writing 12 (2007) 108128 Table 7 Candidate separation statistics DELNA scale Candidate xed chi square Candidate separation ratio 833.5 d.f.: 99 signicance (probability): .00 3.93 TSA-based scale 736.6 d.f.: 99 signicance (probability): .00 4.13

119

the degree to which raters are ranking candidates in a similar fashion. Myford and Wolfe (2004) suggest that the expected values for this correlation are between .3 and .7, with a correlation of .7 being high for rating data. The point biserial correlation coefcient for the DELNA scale is .63, whilst the TSA-based rating scale results in an average correlation coefcient of .67. The ndings from Table 6 indicate that raters, when using the TSA-based scale, with its more dened categories, seemed to be able to not only rank candidates more similarly, but also to achieve consistency in their ratings. Similarly to the rater measurement report described above, FACETS also generates a candidate measurement report. The rst group of statistics in this report is the candidate separation statistics. The candidate xed chi square tests the assumption that all candidates are of the same level of performance. The candidate xed chi square values in Table 7 indicate that the ratings based on the TSA-based scale are slightly more discriminating (seen by the lower xed chi square value). The same trend can be seen when the candidate separation ratio is examined. The candidate separation ratio indicates the number of statistically signicant levels of candidate performance. This statistic also shows that when raters used the TSA-based scale, their ratings were slightly more discriminating. Although the existing DELNA scale has 6 levels of descriptors for coherence, the raters only separated the candidates into 3.93 levels. The TSA-based scale consists of ve levels and the raters separated the candidates into 4.13 levels when using it. The higher discrimination ability of the new scale is a product of the higher rater point biserial correlation. For the comparison of the rating scale categories, FACETS produces scale category statistics. The tables for the existing DELNA and the TSA-based scale are reproduced in Tables 8 and 9 respectively. The rst column in each table shows the raw scores represented by the two rating scales. Please note that the TSA-based scale has one less category to award, therefore only ranges from four to eight. The second column shows the number of times (counts) each of these scores was used by the raters as a group, the third column shows these numbers as percentages of overall use. When looking at the counts and percentages, it is clear that the raters when using the existing DELNA scale, under-used the outside categories: in particular, category 4 was rarely awarded. This table also underlines the evidence that the raters, when using the existing DELNA scale,

Table 8 Scale category statisticsDELNA scale Score 4 5 6 7 8 9 Counts 3 59 288 299 127 24 (%) 0 7 36 37 16 3 Average measure 1.69 1.43 0.41 1.04 2.46 2.95 Expected measure 2.21 1.46 .38 .98 2.34 3.24 Outt mean square 1.2 1.0 1.0 .9 .8 1.3 Step calibration measure 4.82 2.53 .28 2.58 4.49

120

U. Knoch / Assessing Writing 12 (2007) 108128

Table 9 Scale category statisticsTSA-based scale Score 4 5 6 7 8 Counts 38 165 239 205 153 (%) 5 21 30 26 19 Average measure 2.03 .75 .33 1.49 2.73 Expected measure 2.01 .81 .39 1.49 2.70 Outt mean square 1.0 1.1 1.0 .9 .9 Step calibration measure 2.89 .57 1.10 2.36

displayed a central tendency effect. The scores are far more widely spread when the raters used the TSA-based scale; however level 4 seemed still slightly underused, only being awarded in 5% of all cases. Low frequencies might indicate that the categories are unnecessary or redundant and should possibly be collapsed. Column four indicates the average candidate measures at each scale category. These measures should increase as the scale category increases. This is the case for both scales. When this pattern is seen to be occurring, it shows that the rating scale points are appropriately ordered and are functioning properly. This means that higher ratings do correspond to more of the variable being rated. Column ve shows the expected average candidate measure at each category, as estimated by the FACETS program. The closer the expected and the actual average measures, the closer the outt mean square value in column six will be to 1. It can be seen that the outt mean square values for both scales are generally close to 1, however category 9 of the existing scale is slightly high, which might mean that it is not contributing meaningfully to the measurement of the variable of coherence. Bond and Fox (2001) suggest that this might be a good reason for collapsing a category. Column seven gives the step calibration measures, which denote the point at which the probability curves for two adjacent scale categories cross (Linacre, 1999). Thus, the rating scale category threshold represents the point at which the probability is 50% of a candidate being rated in one or the other of these two adjacent categories, given that the candidate is in one of them. The rating scale category thresholds should increase monotonically and be equally distanced (Linacre, 1999) so that none are too close or too far apart. This is generally the case for both rating scales under investigation. Myford and Wolfe (2004) argue that if the rating scale category thresholds are widely dispersed, the raters might be exhibiting a central tendency effect. This is ever so slightly the case for the existing DELNA scale. Overall, the results from research question two indicate that the raters, when using the TSAbased scale, were able to discern more levels of ability among the candidates and ranked the candidates more similarly. They were also able to use more levels on the scale reliably. All these show evidence that the TSA-based scale functions better than the existing scale. However, the raters differed more in terms of leniency and harshness when using the TSA-based scale, which is undesirable but less crucial in situations where scripts are routinely double-rated. 5.3. RQ3: What are raters perceptions of using TSA in a rating scale as compared to more conventional rating scales when rating writing? The interviews provided some evidence that raters experienced problems when using the less specic level descriptors of the DELNA scale. Rater 12, for example, described his problems when using the DELNA scale in the following quote:

U. Knoch / Assessing Writing 12 (2007) 108128

121

. . . sometimes I look at [the descriptor] Im going what do you mean by that? . . . You just kind of have to nd a way around it cause its not really descriptive enough, yeah Rater 4 provided evidence of a strategy that she resorted to when experiencing problems assigning a level: I just tend to go with my gut feeling. So I dont spend a lot of time worrying about it ... but I think this is a very good example of where, if I have an overall sense that a script is really a seven, Id be likely to give it a seven in coherence. Raters were asked in a questionnaire about their perceptions of the rating scale category of coherence in the TSA-based scale. Four raters commented that it took them a while to get used to the rating scale and that they had concerns about it not being very marker friendly (e.g., Rater 5). Most of these raters, however, mentioned that they became accustomed to the category after having marked a number of scripts. Rater 2, for example, mentioned that he likes the scale because it gives me a lot more guidance than the DELNA scale and I feel that I am doing the writers more justice in this way. One rater, however, commented that the TSA-based scale is narrower than the DELNA coherence scale as it focuses only on topical structure and not on other aspects of coherence. Overall, the raters found the TSA-based scale more objective and more descriptive. 6. Discussion and conclusion The analysis of the 602 writing scripts using TSA analysis was able to show that this measure is successful in differentiating between different prociency levels. The redesign of the categories suggested by Schneider and Connor (1990) was valuable in improving the usefulness of the measure. Especially the new categories of superstructure and coherence breaks were found to be discriminating between different levels of writing ability. Apart from being useful in the context of rating scale development and assessment, this method could be applied to teaching, as was suggested by Connor and Farmer (1990). Overall, TSA analysis was shown to be useful as an objective discourse analytic measure of coherence. The comparison of the ratings based on the two different rating scales was able to provide evidence that the raters rated more accurately when using the TSA-based scale. Raters used more band levels and ranked the candidates more similarly when using this scale. Therefore, when using more specic rating scale descriptors when rating a fuzzy concept such as coherence, raters were able to identify more levels of candidate ability. Helping raters to divide performances into as many ability levels as possible, is the aim of rating scales. The raters, when in doubt which band level to award to a performance when using the more impressionistic descriptors of coherence on the DELNA scale, seemed to resort to two different strategies. Either they used most band levels on the scale, but did so inconsistently, or they overused the band levels 6 and 7 and avoided the extreme levels, especially levels 4 and 9. Whilst this might be less of a problem if the trait is only one of many on an analytic rating scale and the score is reported as an averaged score, in a diagnostic context, in which we would like to report the strengths and weaknesses of a candidate to stakeholders, this might result in a loss of valuable information. Alderson (2005) suggests that diagnostic tests should focus more on specic rather than global abilities, and therefore it could be argued that the TSA-based descriptors might be particularly useful in a diagnostic context.

122

U. Knoch / Assessing Writing 12 (2007) 108128

The interview and questionnaire data also provided evidence that the raters focused more on the descriptors when these were less vague and impressionistic. If we are able to arrive at descriptors which enable raters to rely less on their gut feeling of the overall quality of a writing performance but focus more on the descriptions of performance in the level descriptors, then we inevitably arrive at more reliable and probably more valid ratings. This study was able to show that developing descriptors empirically might be the rst step in this direction. An important consideration with respect to the two scales discussed in this study is practicality. Two types of practicality need to be considered: practicality of scale development and practicality of scale use. The TSA-based scale was clearly more time-consuming to develop than the pre-existing DELNA scale. To do a detailed empirical analysis of a large number of writing performances is labor-intensive and therefore might not be practical in some contexts. The practicality of the scale use is another issue that needs to be considered. In this case, there was evidence from the interviews and questionnaires that raters needed more time when rating with the TSA-based scale. However, most reported becoming accustomed to these more detailed scale descriptors. One limitation of this study is that TSA does not cover all aspects of coherence. So whilst the TSA-based scale is more detailed in its descriptions, some aspects of coherence which raters might look for when using more conventional rating descriptors might be lost, which lowers the content validity of the scale. However, it seems that the existing rating scale also resulted in two raters rating too inconsistently, which might be because they were judging different aspects in different scripts and others overusing the inside scale categories. Lumley (2002) was able to show that when raters are confronted with aspects of writing which are not specically mentioned in the scale descriptors, they inevitably use their own knowledge or feelings to resolve it by resorting to strategies. However, this study was able to show that rating scales with very specic level descriptors can help avoid play-it-safe methods and make it easier to arrive at a level (which is what rating scales are ultimately designed for), even though some content validity is sacriced. It is also important to mention that the raters taking part in this study were far more familiar with the current DELNA scale, having used it for many years. Being confronted with the TSA-based scale for this research project meant a departure from the norm. It is therefore possible that the raters in this study varied more in terms of severity when using the TSAbased scale because they were less familiar with it. It might be possible that if they were to use the TSA-based scale more regularly and receive more training, the variance in terms of leniency and harshness might be reduced. It seems important to ensure that rating patterns over time remain stable, and avoid central tendency effects, by subjecting individual trait scales to regular quantitative and qualitative validation studies, and addressing variations both through rater training (as is usually the case) and better specication of scoring criteria. This research was able to show the value of developing descriptors based on empirical investigation. Even an aspect of writing as vague and elusive as coherence was operationalized for this study. Rating scale developers should consider this method of scale development as a viable alternative to intuitive development methods which are commonly used around the world. Overall, it can be said however that more detailed, empirically developed rating scales might lend themselves to being more discriminating and result in higher levels of rater reliability than more conventional rating scales. Further research is necessary to establish if this is also the case for other traits, as this study only looked at a scale for coherence. Also, it would be interesting to pursue a similar study in the context of speaking assessment.

U. Knoch / Assessing Writing 12 (2007) 108128

123

Appendix A. Criteria for identifying sentence topics (taken from Wu, 1997) 1. Sentence topics are dened as the leftmost NP dominated by the nite verb in the t-unit. It is what the t-unit is about. 2. Exceptions: a. Cleft sentences i It is the scientist who ensures that everyone reaches his ofce on time ii It is Jane we all admire b. Anticipatory pronoun it i It is well known that a society benets from the work of its members ii it is clear that he doesnt agree with me c. Existential there i There often exists in our society a certain dichotomy of art and science ii There are many newborn children who are helpless d. Introductory phrase i Biologists now suggest that language is species-specic to the human race. Appendix B. Box plots comparing TSA over different levels See Figs. 28.

Fig. 2. Proportion of parallel progression over ve DELNA levels.

124

U. Knoch / Assessing Writing 12 (2007) 108128

Fig. 3. Proportion of direct sequential progression over ve DELNA levels.

Fig. 4. Proportion of superstructure over ve DELNA levels.

U. Knoch / Assessing Writing 12 (2007) 108128

125

Fig. 5. Proportion indirect progression over ve DELNA levels.

Fig. 6. Proportion extended progression over ve DELNA band levels.

126

U. Knoch / Assessing Writing 12 (2007) 108128

Fig. 7. Proportion unrelated progression over ve DELNA band levels.

Fig. 8. Proportion coherence breaks over ve DELNA band levels.

U. Knoch / Assessing Writing 12 (2007) 108128

127

References

Alderson, C. (2005). Diagnosing foreign language prociency. The interface between learning and assessment. London: Continuum. Bamberg, B. (1984). Assessing coherence: A reanalysis of essays written for National Assessment of Education Progress. Research in the Teaching of English, 18 (3), 305319. Bond, T. G., & Fox, C. M. (2001). Applying the Rasch model: Fundamental measurement in the human sciences. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum. Burneikait , N., & Zabili t , J. (2003). Information structuring in learner texts: A possible relationship between the topical e ue structure and the holistic evaluation of learner essays. Studies about Language, 4, 111. Cason, G. J., & Cason, C. L. (1984). A deterministic theory of clinical performance rating. Evaluation and the Health Professions, 7, 221247. Cheng, X., & Steffensen, M. S. (1996). Metadiscourse: A technique for improving student writing. Research in the Teaching of English, 30 (2), 149181. Connor, U., & Farmer, F. (1990). The teaching of topical structure analysis as a revision strategy for ESL writers. In: B. Kroll (Ed.), Second language writing: Research insights for the classroom. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Crismore, A., Markkanen, R., & Steffensen, M. S. (1993). Metadiscourse in persuasive writing: A study of texts written by American and Finnish university students. Written Communication, 10, 3971. Elder, C. (2003). The DELNA initiative at the University of Auckland. TESOLANZ Newsletter, 12 (1), 1516. Elder, C., Barkhuizen, G., Knoch, U., & von Randow, J. (2007). Evaluating rater responses to an online rater training program. Language Testing, 24 (1), 3764. Elder, C., & Erlam, R. (2001). Development and validation of the diagnostic English language needs assessment (DELNA): Final Report. Auckland: University of Auckland, Department of Applied Language Studies and Linguistics. Elder, C., Knoch, U., Barkhuizen, G., & von Randow, J. (2005). Individual feedback to enhance rater training: Does it work? Language Assessment Quarterly, 2 (3), 175196. Elder, C., & von Randow, J., (2002). Report on the 2002 Pilot of DELNA at the University of Auckland. Auckland: University of Auckland, Department of Applied Language Studies and Linguistics. Fulcher, G. (1987). Tests of oral performance: The need for data-based criteria. ELT Journal, 41 (4), 287291. Fulcher, G. (1996). Does thick description lead to smart tests? A data-based approach to rating scale construction. Language Testing, 13 (2), 208238. Fulcher, G. (2003). Testing second language speaking. London: Pearson Longman. Hamp-Lyons, L. (1991). Scoring procedures for ESL contexts. In: L. Hamp-Lyons (Ed.), Assessing second language writing in academic contexts. Norwood, NJ: Ablex Publishing Corporation. Hoenisch, S. (1996). The theory and method of topical structure analysis. Retrieved 30 April 2007, from http://www.criticism.com/da/tsa-method.php Hoey, M. (1991). Patterns of lexis in text. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Intaraprawat, P., & Steffensen, M. S. (1995). The use of metadiscourse in good and poor ESL essays. Journal of Second Language Writing, 4 (3), 253272. Jacobs, H., Zinkgraf, S., Wormuth, D., Hartel, V., & Hughey, J. (1981). Testing ESL composition: A practical approach. Rowley, MA: Newbury House. Knoch, U., Read, J., & von Randow, J. (2007). Re-training writing raters online: How does it compare with face-to-face training? Assessing Writing, 12 (1), 2643. Lautamatti, L. (1987). Observations on the development of the topic of simplied discourse. In: U. Connor & R. B. Kaplan (Eds.), Writing across languages: Analysis of L2 text (pp. 87114). Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley. Lee, I. (2002). Teaching coherence to ESL students: a classroom inquiry. Journal of Second Language Writing, 11, 135159. Linacre, J. M. (1999). Investigating rating scale category utility. Journal of Outcome Measurement, 3 (2), 103122. Linacre, J. M. (2006). Facets Rasch measurement computer program. Chicago: Winsteps. Lumley, T. (2002). Assessment criteria in a large-scale writing test: What do they really mean to the raters? Language Testing, 19 (3), 246276. McIntyre, P. N. (1993). The importance and effectiveness of moderation training on the reliability of teachers assessments of ESL writing samples. Unpublished masters thesis, University of Melbourne, Australia. Myford, C. M., & Wolfe, E. W. (2003). Detecting and measuring rater effects using many-facet rasch measurement: Part I. Journal of Applied Measurement, 4 (4), 386422. Myford, C. M., & Wolfe, E. W. (2004). Detecting and measuring rater effects using many-facet Rasch measurement: Part II. Journal of Applied Measurement, 5 (2), 189227.

128

U. Knoch / Assessing Writing 12 (2007) 108128

North, B. (1995). The development of a common framework scale of descriptors of language prociency based on a theory of measurement. System, 23 (4), 445465. North, B. (2003). Scales for rating language performance: Descriptive models, formulation styles, and presentation formats. TOEFL Research Paper. Princeton, NJ: Educational Testing Service. North, B., & Schneider, G. (1998). Scaling descriptors for language prociency scales. Language Testing, 15 (2), 217263. Schneider, M., & Connor, U. (1990). Analyzing topical structure in ESL essays. Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 12 (4), 411427. Tribble, C. (1996). Writing. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Turner, C. E., & Upshur, J. A. (2002). Rating scales derived from student samples: Effects of the scale maker and the student sample on scale content and student scores. TESOL Quarterly, 36 (1), 4970. Upshur, J. A., & Turner, C. E. (1995). Constructing rating scales for second language tests. ELT Journal, 49 (1), 312. Upshur, J. A., & Turner, C. E. (1999). Systematic effects in the rating of second-language speaking ability: Test method and learner discourse. Language Testing, 16 (1), 82111. Watson Todd, R. (1998). Topic-based analysis of classroom discourse. System, 26, 303318. Watson Todd, R., Thienpermpool, P., & Keyuravong, S. (2004). Measuring the coherence of writing using topic-based analysis. Assessing Writing, 9, 85104. Weigle, S. C. (1994). Effects of training on raters of English as a second language compositions: Quantitative and qualitative approaches. University of California, Los Angeles: Unpublished doctoral dissertation. Weigle, S. C. (1994). Effects of training on raters of ESL compositions. Language Testing, 11 (2), 197223. Weigle, S. C. (1998). Using FACETS to model rater training effects. Language Testing, 15 (2), 263287. Witte, S. (1983). Topical structure analysis and revision: An exploratory study. College Composition and Communication, 34 (3), 313341. Witte, S. (1983). Topical structure and writing quality: Some possible text-based explanations of readers judgments of students writing. Visible Language, 17, 177205. Wright, B. D., & Masters, G. N. (1982). Rating scale analysis. Chicago: MESA Press. Wu, J. (1997). Topical structure analysis of English as a second language (ESL) texts written by college Southeast Asian refugee students. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, University of Minnesota.

Você também pode gostar

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeNo EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (5794)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreNo EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (1090)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItNo EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceNo EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (890)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureNo EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (474)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersNo EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (344)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)No EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Nota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (119)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerNo EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingNo EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (399)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyNo EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (2219)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)No EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Nota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaNo EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (265)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryNo EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnNo EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (234)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaNo EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (45)

- Character Strengths and VirtuesDocumento2 páginasCharacter Strengths and Virtuesapi-237925148Ainda não há avaliações

- (Research Methods in Linguistics) Aek Phakiti-Experimental Research Methods in Language Learning-Continuum Publishing Corporation (2014) PDFDocumento381 páginas(Research Methods in Linguistics) Aek Phakiti-Experimental Research Methods in Language Learning-Continuum Publishing Corporation (2014) PDFYaowarut Mengkow100% (1)

- Feasibility ProposalDocumento3 páginasFeasibility Proposalapi-302337595Ainda não há avaliações

- English 7 DLL Q2 Week 8Documento6 páginasEnglish 7 DLL Q2 Week 8Anecito Jr. NeriAinda não há avaliações

- Perimeter and Area of RectanglesDocumento2 páginasPerimeter and Area of RectanglesKaisha MedinaAinda não há avaliações

- DepEd RADaR Report FormsDocumento2 páginasDepEd RADaR Report FormsBrown Cp50% (2)

- DLL Tle 10 HSDocumento4 páginasDLL Tle 10 HSLOIDA LAMOSTEAinda não há avaliações

- CreativewritingsyllabusDocumento5 páginasCreativewritingsyllabusapi-261908359Ainda não há avaliações

- 05-OSH Promotion Training & CommunicationDocumento38 páginas05-OSH Promotion Training & Communicationbuggs115250% (2)

- Teaching Science in Primary GradesDocumento26 páginasTeaching Science in Primary GradesRica Noval CaromayanAinda não há avaliações

- Practical Ethnography SampleDocumento39 páginasPractical Ethnography SampleSandra VilchezAinda não há avaliações

- UF InvestigationDocumento72 páginasUF InvestigationDeadspinAinda não há avaliações

- 6 KZPK 7 Cqs 9 ZazDocumento24 páginas6 KZPK 7 Cqs 9 ZazNelunika HarshaniAinda não há avaliações

- District Project Office Sarva Shiksha Abhiyan, Sambalpur: AdvertisementDocumento4 páginasDistrict Project Office Sarva Shiksha Abhiyan, Sambalpur: AdvertisementRupali PanigrahiAinda não há avaliações

- Vice Chancellor's message highlights WUM's missionDocumento115 páginasVice Chancellor's message highlights WUM's missionhome143Ainda não há avaliações

- Recirpocal Teaching Discussion Self-Assessment With RubricDocumento7 páginasRecirpocal Teaching Discussion Self-Assessment With RubricedyoututorAinda não há avaliações

- Compound SentencesDocumento4 páginasCompound SentenceswahidasabaAinda não há avaliações

- Sample Pa Ges CatalogueDocumento16 páginasSample Pa Ges CatalogueEndi100% (2)

- DLL - Tle 6 - Q2 - W6Documento3 páginasDLL - Tle 6 - Q2 - W6Rhadbhel Pulido100% (6)

- Chapter 3 The Life of Jose Rizal PDFDocumento11 páginasChapter 3 The Life of Jose Rizal PDFMelanie CaplayaAinda não há avaliações

- Art App Lesson PlanDocumento3 páginasArt App Lesson Planapi-354923074100% (1)

- COMPRE EXAM 2021 EducationalLeadership 1stsem2021 2022Documento7 páginasCOMPRE EXAM 2021 EducationalLeadership 1stsem2021 2022Severus S PotterAinda não há avaliações

- Team Sports Fall Semester Syllabus ADocumento4 páginasTeam Sports Fall Semester Syllabus Aapi-418992413Ainda não há avaliações

- ObjectivesDocumento5 páginasObjectivesRachelle Anne MalloAinda não há avaliações

- Digital Unit Plan Template 1 1 17 4Documento4 páginasDigital Unit Plan Template 1 1 17 4api-371629890100% (1)

- Csce 1030-002 SP15Documento6 páginasCsce 1030-002 SP15hotredrose39Ainda não há avaliações

- NCHE - Benchmarks For Postgraduate StudiesDocumento73 páginasNCHE - Benchmarks For Postgraduate StudiesYona MbalibulhaAinda não há avaliações

- Competency Proficiency Assessment OrientationDocumento44 páginasCompetency Proficiency Assessment OrientationKrisna May Buhisan PecoreAinda não há avaliações

- Asd-W School Calendar 2016-2017 ColoredDocumento1 páginaAsd-W School Calendar 2016-2017 Coloredapi-336438079Ainda não há avaliações

- Brigada Eskwela ManualDocumento19 páginasBrigada Eskwela ManualEdwin Siruno LopezAinda não há avaliações