Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

Status of Women and Girls New Haven Report

Enviado por

Helen Bennett0 notas0% acharam este documento útil (0 voto)

2K visualizações136 páginasInstitute for Women's Policy Research conducts rigorous research and disseminates its findings. Status of women reports have been written for all 50 states and the District of Columbia. IWPR's work is supported by foundation grants, government grants and contracts.

Descrição original:

Direitos autorais

© Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Formatos disponíveis

PDF, TXT ou leia online no Scribd

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoInstitute for Women's Policy Research conducts rigorous research and disseminates its findings. Status of women reports have been written for all 50 states and the District of Columbia. IWPR's work is supported by foundation grants, government grants and contracts.

Direitos autorais:

Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Formatos disponíveis

Baixe no formato PDF, TXT ou leia online no Scribd

0 notas0% acharam este documento útil (0 voto)

2K visualizações136 páginasStatus of Women and Girls New Haven Report

Enviado por

Helen BennettInstitute for Women's Policy Research conducts rigorous research and disseminates its findings. Status of women reports have been written for all 50 states and the District of Columbia. IWPR's work is supported by foundation grants, government grants and contracts.

Direitos autorais:

Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Formatos disponíveis

Baixe no formato PDF, TXT ou leia online no Scribd

Você está na página 1de 136

The Status of

Hsora & Cr|

New Haven

1200 18th St. NW, Suite 301

Washington, DC 20036

Phone: (202) 785-5100

Fax: (202) 833-4362

N

e

w

H

a

v

e

n

,

C

o

n

n

e

c

t

i

c

u

t

in NewHaven, Connecticut

About the Institute for

Womens Policy Research

The Institute for Womens Policy Research (IWPR)

conducts rigorous research and disseminates its findings

to address the needs of women, promote public

dialogue, and strengthen families, communities, and

societies. The Institute works with policymakers, scholars,

and public interest groups to design, execute, and

disseminate research that illuminates economic and social

policy issues affecting women and their families, and to

build a network of individuals and organizations that

conduct and use women-oriented policy research. IWPRs

work is supported by foundation grants, government

grants and contracts, donations from individuals, and

contributions from organizations and corporations. IWPR

is a 501(c)(3) tax-exempt organization that also works in

affiliation with the womens studies and public policy

programs at The George Washington University.

Since 1996, IWPR has produced an ongoing series of

reports on the status of women and girls in states and

localities throughout the United States. Status of women

reports have been written for all 50 states and the District

of Columbia and have been used throughout the country

to highlight womens progress and the obstacles they

continue to face and to encourage policy and

programmatic changes that can improve womens

opportunities. Created in partnership with local advisory

committees, the reports have helped state and local

partners achieve multiple goals, including educating the

public on issues related to womens and girls well-being,

informing policies and programs, making the case for

establishing commissions for women, helping donors and

foundations establish investment priorities, and inspiring

community efforts to strengthen economic circumstances

by improving womens status.

The Status of Women and Girls

in New Haven, Connecticut

Cynthia Hess, Ph.D.

Rhiana Gunn-Wright

Claudia Williams

IWPR #R355, July 2012

ISBN 978-1-878428-03-05

Library of Congress 2012940696

$20.00

Copyright 2012 by the Institute for Womens

Policy Research, Washington, DC.

All rights reserved.

Printed in the United States of America.

About This Report

This report is the result of conversations over nearly two

years among women leaders in New Haven about the

growing need for data on women and girls in New Haven.

The report has four goals: 1) to provide baseline

information on women and girls in New Haven; 2) to

inform policy and program priorities for women and girls in

New Haven; 3) to provide easily accessible data on women

and girls in New Haven; and 4) to create a platform for

advocacy and dialogue on issues affecting women and

girls in New Haven. The report was written by the Institute

for Womens Policy Research (IWPR) in partnership with

the Consortium for Women and Girls in New Haven under

a contract with the City of New Haven.

In producing this report, IWPR collaborated with many

individuals and organizations in New Haven. Dr. Chisara

Asomugha and Dr. Carolyn Mazure served as co-chairs of

the Consortium for Women and Girls and coordinated the

work of the Consortium, which is comprised of individuals

who work in diverse fields, including law enforcement,

womens health, education, philanthropy, immigration

services, business development, and employment services.

As co-chairs, Drs. Asomugha and Mazure managed all the

Consortium activities, including organizing meetings,

facilitating the review of the report by the Consortium

members and the Critical Review Panel (see list of panel

members below), editing the report, and coordinating the

writing of program descriptions to include in the text. The

Consortium co-chairs and members also helped select the

indicators for the report to ensure that the data analysis

would be useful, publicly presented the report findings,

and organized the publicity surrounding the report. Many

additional organizations and agencies in New Haven

collaborated with IWPR and the Consortium in this project

by providing data for the report on topics such as

domestic violence, womens health, housing, and political

participation.

About The Consortium for

Women and Girls in New Haven

Created and convened by Dr. Chisara N. Asomugha,

Community Services Administrator for New Haven and

co-chaired by Dr. Carolyn Mazure, Director for Womens

Health Research at Yale, the Consortium for Women and

Girls in New Haven represents various sectors and

communities in New Haven. Members of the Consortium

were tasked with obtaining local data and providing the

framework for a quantitative report on the status of

women and girls in New Haven. Members recognized

that the data could provide a common platform for New

Haven to address issues that affect women and girls.

The Status of

Hsora & Cr|

in NewHaven, Connecticut

Cynthia Hess, Ph.D.

Rhiana Gunn-Wright

Claudia Williams

Acknowledgments

This report was generously funded by the Community Fund for Women & Girls at

The Community Foundation for Greater New Haven, United Illuminating, Yale

New Haven-Hospital, New Haven Healthy Start, and the Junior League of Greater

New Haven. It was also supported with funding from grant #CCEWH111021 [The

New Haven Mental Health Outreach for Mothers (MOMS) Partnership] from the

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS)/Office on Womens

Health. Additional funding was provided by the Institute for Womens Policy

Research with support from the Annie E. Casey Foundation and the Ford

Foundation. The Chairs of the Consortium for New Haven Women and Girls

acknowledge the staff support provided by Lynn Lyons, Connie Cho, Zoe Mercer-

Golden, Kerri Lu, and Ariel Morriar, and the tremendous effort of the Consortium

Members (see list below). The Consortium also thanks former Assistant Police

Chief Petisia Adger and members of the Critical Review Panel, whose comments

strengthened the report. Members of the panel include Mark Abraham, Penny

Canny, Amy Casavina-Hall, Kelly Chapman, Amanda Durante, Ellen Durnin,

Esther Howe, Dorsey Kendrick, Laoise King, Shirley Jackson, New Haven MOMs

Partnership Community Mental Health Ambassadors, Shelly Saczynski, Barbara

Segaloff, Barbara Tinney, Dacia Toll, Susan Yolen, and Teresa Younger.

The authors of this report thank the Consortium Members, especially Co-Chairs

Chisara Asomugha and Carolyn Mazure, for their intensive work on the project.

Dr. Asomugha provided invaluable support in acquiring local data and

coordinating committee input in her role as the projects primary point of contact.

The authors would also like to acknowledge Institute for Womens Policy Research

(IWPR) staff who contributed to the production of this report. The authors thank

Barbara Gault, IWPRs Vice President and Executive Director, for her advice and

guidance throughout the various project phases. Heidi Hartmann, IWPRs

President, and Ariane Hegewisch, Study Director, gave helpful feedback on the

report. Caroline Dobuzinskis, Communications Manager, and Mallory Mpare,

Communications Assistant, provided valuable editorial assistance. Research

assistance was provided by Research Fellow Justine Augeri, Research and Program

Assistant Youngmin Yi, and Research Interns Jessica Emami, Clara Hanson, Vanessa

Harbin, Zoe Li, Sarah Murphy, Maureen Sarna, and Anlan Zhang. In addition, the

Institute thanks the organizations and agencies who provided data for the report,

including the Birmingham Group Health Services, the City of New Haven, the

Community Alliance for Research and Engagement at Yale, the Connecticut State

Police, the New Haven Health Department, New Haven Healthy Start, the New

Haven Police Department, New Haven Promise, and the New Haven Public

Schools.

Finally, the Consortium and IWPR acknowledge all the womenand menwho

laid the groundwork for progressive change in New Haven. It is upon this history

and passion that this report is made possible.

Foreword

What began as an idea nearly two years ago has materialized into a

comprehensive portrait of women and girls in New Haven. A thoughtful, diverse,

and powerful group of women with extensive ties to the New Haven community

came together in a meeting room and asked, What is the status of women and

girls in New Haven? And our answer became the impetus for this unprecedented

effort to paint a clear and compelling picture of New Havens women and girls.

Understanding the disparities that women and girls face in health, education,

economic security, and earning potential as well as in safety and political

leadership, this group set out to obtain and compile the data that would highlight

the challenges faced by women and girls in our community. The resulting

document is meant for policymakers, advocates, and communities to review and

use as a tool for advancing the lives of women and girls and thus improve the

well-being of the entire community.

This report has four main goals:

I To Provide Baseline Information on Women and Girls in New Haven

This report provides a foundation from which we can measure progress

and assess the impact of policies and programs in New Haven that affect

women and girls.

I To Inform Policy and Program Priorities for Women and Girls in New

Haven

This report provides community organizations and leaders, policymakers,

advocates, and residents with information on women and girls that can

inform their initiatives.

I To Provide Easily Accessible Data on Women and Girls in New Haven

While New Haven has numerous organizations that collect various types

of data on women and girls, until now the data have not been compiled

in one place that is easily accessible to community stakeholders.

I To Create a Platform for Advocacy and Dialogue on Issues Affecting

Women and Girls in New Haven

New Haven has historically been a proving ground for progressive change

and remains at the forefront of innovative social policy. Following this

tradition, this status report on New Havens women and girls provides an

important opportunity for New Haven to give voice to women and girls

at a critical time in our history and prioritize their needs to create a

stronger community.

We are excited about this report and its potential to leverage resources that will

improve the status of women and girls in New Haven. And while all the data it

presents cannot capture every facet of womens lives, we hope that the report and

the dialogue and action it fosters will ensure that New Havens residents can

benefit from a quality education, enjoy healthy lives and families, achieve

economic security, and actively engage in the community.

i

The Status of Women & Girls in New Haven, Connecticut

Chisara N. Asomugha,

M.D., MSPH, FAAP

Carolyn M. Mazure, Ph.D.

Co-Chairs, Consortium for

New Haven Women and Girls

The Status of Women & Girls in New Haven, Connecticut

ii

Ms. Nancy Alexander

Consultant and Past Chair

Community Fund for Women

and Girls

Dr. Chisara N. Asomugha*

Community Services Administrator

City of New Haven

Sister Mary Ellen Burns

Director

Apostle Immigrant Services

Ms. Sharon Cappetta

Director of Development

Community Foundation for Greater

New Haven

Ms. Maria Damiani

Director of Womens Health

New Haven Health Department

Ms. Suzannah Holsenbeck

Yale Co-Op Partnership Coordinator

Director of Co-Op After School

Cooperative Arts & Humanities High

School

Ms. Mubarakah Ibraham

Chief Executive Officer

Balance Fitness

Ms. Latrina Kelly

Development Director

Junta for Progressive Action

Ms. Jillian Y. Knox

Police Officer

New Haven Police Department

Dr. Carolyn Mazure*

Director, Womens Health

Research at Yale

Professor of Psychiatry

Yale University School of Medicine

Ms. Ebony McClease

Graduate Assistant, Womens

Studies Program

Graduate Intern, Womens Center

Southern Connecticut State University

Dr. Megan V. Smith

Assistant Professor of Psychiatry &

in the Child Study Center

Yale BIRCWH Scholar (NIH

OWRH/NIDA/NIAAA

Building Interdisciplinary Research

Careers in Women's Health Program)

Yale University School of Medicine

Ms. Lynn Smith

Senior Vice President of Community

and Business Development

Start Community Bank

Ms. Sandra Trevino

Executive Director

Junta for Progressive Action

Ms. Tomi Veale

Coordinator, Youth@Work

Youth Department

City of New Haven

Ms. Patricia Wallace

Director, Elderly Services Department

City of New Haven

Ms. Shirley Ellis-West

Supervisor of Street Outreach

New Haven Family Alliance

*Consortium Co-Chairs

iii

The Status of Women & Girls in New Haven, Connecticut

Consortium Members

The Status of Women & Girls in New Haven, Connecticut

iv

Contents

Executive Summary..................................................................................................1

I. Introduction....................................................................................................5

II. Employment and Earnings ..........................................................................13

III. Economic Security ......................................................................................29

IV. Education......................................................................................................41

V. Health and Well-Being ................................................................................53

VI. Crime and Safety..........................................................................................67

VII. Political Participation and Leadership ........................................................77

VIII. Creating a Brighter Future for Women and Girls in New Haven ..............87

Appendix I: Methodology ....................................................................................91

Appendix II: Tables ................................................................................................93

References ............................................................................................................107

v

The Status of Women & Girls in New Haven, Connecticut

List of Figures

Figure 1.1. Percent of Female Residents by Race/Ethnicity,

New Haven, 20082010 ........................................................................7

Figure 1.2. Percent of Female Residents by Race/Ethnicity,

Connecticut, 20082010........................................................................7

Figure 1.3. Age Distribution of Women and Girls by Race/Ethnicity,

New Haven, 20082010 ........................................................................8

Figure 1.4. Female Immigrants by Place of Birth, New Haven, 20082010 ........10

Figure 1.5. Marital Status by Gender and Nativity,

New Haven and Connecticut, 20082010..........................................10

Figure 2.1. Percent of Women and Men in the Labor Force,

16 Years and Older, New Haven, Connecticut,

and United States, 20082010 ............................................................15

Figure 2.2. Labor Force Participation Among Women Aged 55

and Older in New Haven, Connecticut, and

United States, 20082010....................................................................15

Figure 2.3. Unemployment Rates by Gender in New Haven, Connecticut,

and United States, 20082010 ............................................................18

Figure 2.4. Unemployment Rates by Gender and Race/Ethnicity,

New Haven, 20082010 ......................................................................18

Figure 2.5. Ratio of Women's to Men's Full-Time/Year-Round Median Annual

Earnings by Race/Ethnicity in New Haven, Connecticut, and

United States, 20082010....................................................................21

Figure 2.6. Distribution of Women and Men Across Broad Occupational

Groups in New Haven, 20082010 ....................................................23

Figure 2.7. Womens Distribution Across Employment

Sectors in New Haven, 20082010 ....................................................26

Figure 3.1. Median Annual Income by Household Type in New Haven,

Connecticut, and United States, 20082010......................................31

Figure 3.2. Poverty Rates by Gender in New Haven, Connecticut,

and United States, 20082010 ............................................................32

Figure 3.3. Poverty Rates by Gender and Race/Ethnicity,

New Haven, 20082010 ......................................................................33

The Status of Women & Girls in New Haven, Connecticut

vi

vii

The Status of Women & Girls in New Haven, Connecticut

Figure 3.4. Poverty Rates for Selected Family Types in New Haven,

Connecticut, and United States, 20082010......................................34

Figure 3.5. Poverty Rates by Gender and Age in New Haven,

Connecticut, and United States, 20082010......................................36

Figure 3.6. Percent of All Households and Households

with Children Receiving Food Stamps in New Haven,

Connecticut, and United States, 20082010......................................38

Figure 4.1. Dropout Rates by Gender for New Haven and

Connecticut, 20032010......................................................................46

Figure 4.2. Percent of English Language Learners in New Haven and

Connecticut Public Schools, 20012011 ............................................47

Figure 4.3. Educational Attainment of Women and Men

Aged 25 Years and Older in New Haven,

Connecticut, and United States, 20082010......................................48

Figure 4.4. Educational Attainment of Women Aged 25 and

Older by Race/Ethnicity, New Haven, 20082010 ............................49

Figure 4.5. Median Annual Earnings by Gender and Educational Attainment,

Aged 25 Years and Older, New Haven, 20062010............................50

Figure 4.6. Poverty Rates for the Population Aged 25 Years and

Older by Educational Attainment and Gender,

New Haven, 20082010 ......................................................................51

Figure 5.1. Breast Cancer Incidence Rates by Race/Ethnicity,

New Haven County and Connecticut, 20052009 ............................57

Figure 5.2. Crude Mortality Rates for Breast Cancer per 100,000 Women

by Race/Ethnicity, New Haven, 20052009 ......................................59

Figure 5.3. Percent of Women Receiving Non-Adequate

Prenatal Care by Race/Ethnicity, New Haven, 2008..........................61

Figure 5.4. Annual Infant Mortality Rates per 1,000

Live Births by Race/Ethnicity, New Haven, 20052009....................62

Figure 5.5. Teen Birth Rates in New Haven per 1,000 Teens Aged 1519

by Race/Ethnicity, New Haven, 2000, 2006, and 2008 ....................64

Figure 6.1. Type of Youth Violence

Perpetrated by Gender, New Haven, 2010..........................................72

Figure 6.2. Percent of High School Students Feeling Unsafe or

Experiencing Violence or Harassment by Gender,

Connecticut, 2009................................................................................74

Figure 6.3. Percent of High School Students Experiencing Dating

Violence by Type of Violence and Gender, Connecticut, 2009 ........74

Figure 7.1. Political Identification Among Registered

Voters by Gender, New Haven, 2012 ..................................................79

Figure 7.2. Numbers of Women and Men Employed in

City Government, New Haven, 2011 ................................................81

Figure 7.3. Numbers of Women Employed in City Government

by Race/Ethnicity, New Haven, 2011 ................................................82

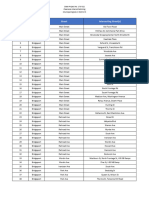

List of Tables

Table 2.1. Disability Limits or Prevents Work by Gender,

New Haven and Connecticut, 20092011..........................................16

Table 2.2. Disability Limits or Prevents Work by Gender and

Race/Ethnicity, Connecticut, 20092011 ..........................................16

Table 2.3. Median Annual Earnings of Women and Men Employed

Full-Time/Year-Round by Race/Ethnicity in New Haven,

Connecticut, and United States, 20082010......................................20

Table 2.4. Womens and Mens Median Annual Earnings Across Broad

Occupational Groups in New Haven and Connecticut,

20082010 ............................................................................................24

Table 4.1. Percentage of Third Through Eighth Graders Who Scored At or

Above Proficiency on Math, Reading, Science, and Writing

by Gender, New Haven, 20102011 ..................................................44

Table 4.2. Average SAT Scores by Gender,

New Haven and Connecticut, 2011....................................................45

Table 4.3. Poverty Rates by Gender and Educational Attainment in

New Haven, Connecticut, and United States, Aged 25 Years

and Older, 20082010 ........................................................................52

Table 5.1. Health Insurance Coverage by Gender and Race/Ethnicity in New

Haven, Connecticut, and United States, 20082010 ........................55

Table 5.2. Crude Mortality Rates per 100,000 for Selected Causes by Gender

and Race/Ethnicity, New Haven, 20052009 ....................................59

Table 5.3. Babies Born with Low Birth Weight as Percent of All Births, by Race

and Ethnicity of Mother, New Haven and Connecticut, 2008 ........63

Table 6.1. Violent Crime in New Haven in 1990, 2000, and 2010 ....................69

The Status of Women & Girls in New Haven, Connecticut

viii

List of Appendix Tables

Table 1 Distribution of Women and Girls by Age, New Haven and

Connecticut, 20082010......................................................................93

Table 2 Distribution of Households by Type, New Haven and

Connecticut, 20082010......................................................................93

Table 3 Immigrant and Native-Born Populations by Gender and Age in

New Haven, Connecticut, and United States, 20082010 ................94

Table 4 Median Annual Earnings by Gender and Nativity in New Haven,

Connecticut, and United States, 20082010......................................94

Table 5 Distribution of Women Across Broad Occupational Groups by

Race/Ethnicity, New Haven, 20082010............................................95

Table 6 Distribution of Women Across Broad Occupational Groups by

Race/Ethnicity, Connecticut, 20082010 ..........................................96

Table 7 Distribution of Women Across Broad Occupational Groups by

Race/Ethnicity, United States, 20082010 ........................................97

Table 8 Percent of Students Enrolled in Public Schools in the New Haven

School District by Race/Ethnicity, 2011 ............................................98

Table 9 Educational Attainment of Women and Men Aged 25 and

Older by Nativity in New Haven, Connecticut, and United States,

20082010 ............................................................................................98

Table 10 Educational Attainment of Women Aged 25 and Older by

Race/Ethnicity in New Haven, Connecticut, and United States,

20082010 ............................................................................................99

Table 11 Median Annual Earnings by Gender and Educational Attainment in

New Haven, Connecticut, and United States, 20062010 ..............100

Table 12 Numbers and Rates of Asthma Hospitalizations per 10,000 Among

Adults Aged 18 and Older by Gender, New Haven and Connecticut

(Minus Five Largest Cities), 20012005............................................100

Table 13 Numbers and Rates of Asthma Hospitalizations per 10,000 Among ..

Children Aged 017 by Gender, New Haven and Connecticut (Minus

Five Largest Cities), 20012005 ........................................................101

Table 14 Numbers and Rates of Asthma Hospitalizations per 10,000 Among

Adults Aged 18 and Older by Race/Ethnicity, New Haven and

Connecticut (Minus Five Largest Cities), 20012005 ....................101

ix

The Status of Women & Girls in New Haven, Connecticut

Table 15 Numbers and Rates of Asthma Hospitalizations per 10,000 Among

Children Aged 017 by Race/Ethnicity, New Haven and Connecticut

(Minus Five Largest Cities), 20012005............................................102

Table 16 Age-Adjusted Mortality Rates per 100,000 for Selected Causes by

Gender and Race, New Haven, 20052009 ......................................102

Table 17 Average Annual Count and Incidence Rates per 100,000 for Cervical

Cancer by Race/Ethnicity, New Haven County and Connecticut,

20052009 ..........................................................................................103

Table 18 Average Annual Count and Incidence Rates per 100,000 for Ovarian

Cancer by Race/Ethnicity, New Haven County and Connecticut,

20052009 ..........................................................................................103

Table 19 Numbers and Rates of Teen Births per 1,000 Teens by Race/

Ethnicity, New Haven and Connecticut, 2000, 2006, and 2008 ....104

Table 20 Chlamydia Diagnoses and Rates per 10,000 (Aged 10 and

Older) by Gender and Race/Ethnicity, New Haven, 2010 ..............104

Table 21 Gonorrhea Diagnoses and Rates per 10,000 (Aged 10 and Older)

by Gender and Race/Ethnicity, New Haven, 2010 ..........................105

Table 22 Chlamydia Diagnoses and Rates per 10,000 Among Women

Aged 10 and Older by Race/Ethnicity, New Haven and

Connecticut, 2010..............................................................................105

Table 23 Gonorrhea Diagnoses and Rates per 10,000 Among Women

Aged 10 and Older by Race/Ethnicity, New Haven and

Connecticut, 2010..............................................................................106

Table 24 Gonorrhea and Chlamydia Diagnoses Among Women and

Girls by Age, New Haven, 2010 ......................................................106

The Status of Women & Girls in New Haven, Connecticut

x

Executive

Summary

H

omen and girls in New Haven, Connecticut, have experienced

remarkable social, economic, and political progress in recent decades,

but the need for further improvements remains. Many of New Havens

women and girls are vulnerable to challenges such as poverty, long-term economic

insecurity, domestic violence, and specific adverse health conditions. In addition,

women and girls experience stubborn racial and ethnic disparities in opportunities

and outcomes. Addressing these challenges and disparities is essential to the health

and vibrancy of the city; when women and girls thrive, whole communities thrive.

This report provides information, using the most recent available data, to help

pinpoint areas where progress is needed to speed womens and girls

advancement. Drawing on multiple data sources, it analyzes issues that

profoundly affect the lives of women and girls: employment and earnings,

economic security, education, health and well-being, crime and safety, and

political participation and leadership. The data are intended to serve as a resource

for advocates, researchers, community leaders, and members of the public who

seek to analyze and discuss community investments and program initiatives that

will lead to sustained positive change.

Key findings include the following:

I Women and girls in New Haven constitute a diverse group. Among the

more than 68,000 women and girls who live in the city, blacks make up the

largest share (37 percent), followed by whites (32 percent) and Hispanics (23

percent). This is quite different from the composition of the female

population in Connecticut as a whole, which is largely (72 percent) white.

1

I Women in New Haven are less likely than men to be married. Only about

one in four women (26 percent) in the city aged 18 and older is married,

compared with more than three in ten men (32 percent). Both women

and men in New Haven are much less likely than women and men in

Connecticut to be married. In the state, half of women (50 percent) and

more than half of men (56 percent) aged 18 and older are married.

I Twenty-three percent of all households in New Haven are headed by

single women (with and without dependent children), compared with just

13 percent in the state as a whole. Only one in four households in New

Haven is headed by a married couple, a significantly smaller proportion

than in Connecticut as a whole (50 percent).

I Despite their increased participation in the workforce, womens wages

continue to lag behind mens. On average, women in New Haven earn

significantly less than men in the city: womens median annual earnings

are $37,530, compared with $42,433 for men. Womens median annual

earnings in New Haven are also much less than womens ($45,379) and

mens ($60,344) median annual earnings in Connecticut, but slightly

more than womens median annual earnings in the United States overall

($36,142).

I More than one-quarter of New Havens residents live below the federal

poverty line and more than half of those living in poverty are female.

Among the citys female population, Hispanics and blacks are

significantly more likely to be poor (43 percent and 30 percent,

respectively) than whites (17 percent) and Asians (19 percent).

I Girls in New Havens public schools outperform boys in many respects.

On the 2011 Connecticut Mastery Test, girls in New Haven in grades

three through eight scored higher than boys on nearly every section of

the test, including in mathematics (in all grades except third and sixth)

and in fifth and eight grade science, the only years for which data are

available by sex in this subject. In high school, the citys girls also have

lower dropout rates than boys and receive, on average, higher writing

scores on the SAT.

I Education is critical to womens economic security. Nearly half (47

percent) of women in New Haven with less than a high school diploma

live in poverty, compared with 12 percent of those with a bachelors

degree or higher. Among men, the proportion of those without a high

school diploma who live in poverty is significantly lower (29 percent).

Only 10 percent of men in New Haven with a college or advanced degree

live in poverty.

I In New Haven, as in the United States as a whole, women earn less than

men with similar levels of education, leading to a persistent gender wage

gap.

2

The Status of Women & Girls in New Haven, Connecticut

I Women in New Haven are more likely to have health insurance than

men. White women have the highest rate of coverage among women and

men in the city at 95 percent. Hispanic men have the lowest coverage rate

(58 percent), followed by Hispanic women (79 percent). Although women

overall have higher rates of coverage than men, significant disparities exist

between women of different races and ethnicities. Twenty-one percent of

Hispanic women in New Haven are uninsured, compared with five

percent of white women and ten percent of black women.

I The availability of reliable, gender-specific health data for New Haven

City varies greatly by health condition. Particularly pressing gaps in data

include information about cardiovascular disease, various forms of

cancer, mental health conditions, and addictive behaviors, including

smoking.

I As in many urban areas, births to teenage mothers are an issue of concern

in New Haven. Although teen birth rates in New Haven have dropped

considerably in the past decade, from 60.6 per 1,000 girls in 2000 to 46.0

per 1,000 in 2008, teen birth rates (to girls aged 1519) in New Haven are

double the rates for Connecticut, with black and Hispanic girls

comprising about 94 percent of all births to teenage mothers in the city

in 2008.

I Changes to public policies and program initiatives provide opportunities

to create a better future for women and girls in New Haven.

Recommended changes include encouraging employers to take steps to

remedy gender wage inequities, supporting women-led, women-initiated

businesses and female-specific programs in New Haven, implementing

strong career and education counseling for girls beginning in elementary

school, and creating a comprehensive health curriculum in the New

Haven School District that addresses physical and mental health,

including the prevention of dating violence and the advancement of

reproductive health.

I Better mechanisms for data collection and sharing across agencies are

needed to track progress for New Havens women and girls on key

indicators.

The economic, social, and political disparities that women and girls continue to

experience, as well as their significant progress, reveal the need to explore

opportunities to further advance the status of women and girls in New Haven

and the United States as a whole. Especially now, as the nation strives to move

beyond an economic recession in which women suffered substantial losses and

have experienced an especially slow recovery, it is imperative that womens

interests and concerns fully inform policymaking, service provision, advocacy,

and program initiatives. This report aims to provide information that can be used

to help ensure that this goal becomes a reality.

The Status of Women & Girls in New Haven, Connecticut

3

4

The Status of Women & Girls in New Haven, Connecticut

5

7

he status of women and girls is a key component of the overall health and

well-being of New Haven, Connecticut. Investing in initiatives that address

the needs of New Havens women and girls can improve not only their

circumstances, but also the economic standing, health, and well-being of the entire

community. When women and girls thrive, whole communities thrive.

Local initiatives that focus on women and girls must address the complex realities

of their lives. On the one hand, women and girls in New Haven have made

significant social, economic, and political progress in recent decades. Women who

live in New Haven today are active in the workforce, head local organizations, run

their own businesses, volunteer in their communities, participate in social justice

movements, and get involved in local politics. Their leadership and activism has a

long tradition in the city: in the early 1950s, more than 370 formally organized

womens clubs existed in New Haven (Minnis 1953). By the 1970s, a strong

womens movement had developed in the city, involving a large number of women

who believed in the power of collective action to create change (Kesselman 2001).

Women have playedand continue to playa vital role in making New Haven a

more vibrant community for all.

On the other hand, women in New Haven, as in Connecticut and the nation as a

whole, continue to experience specific challenges that reveal the slow nature of

change. Women at all educational levels earn less than men and are more likely to

live in poverty. Women are also disproportionately vulnerable to certain types of

violence and are often underrepresented in public office. In addition, women and

girls in New Haven experience persistent racial and ethnic disparities in

I.

Introduction

More than 68,000

women and girls live

in New Haven,

comprising 53

percent of the citys

total population.

1

The American Community Survey (ACS) population count includes both households and

group quarter (GQ) facilities, which include places such as college residence halls, residential

treatment centers, skilled nursing facilities, group homes, military barracks, correctional

facilities, workers dormitories, and facilities for people experiencing homelessness. Certain

group quarter facilities are excluded from ACS sampling and data collection, including

domestic violence shelters, soup kitchens, regularly scheduled mobile vans, targeted non-

sheltered outdoor locations, commercial maritime vessels, natural disaster shelters, and

dangerous encampments.

6

The Status of Women & Girls in New Haven, Connecticut

opportunities and outcomes. These challenges and disparities are often under-

recognized but must be addressed for the city as a whole to thrive.

Those working to understand and improve womens and girls circumstances need

reliable data on the status of New Havens female residents. This report seeks to

address this need by analyzing how women and girls in New Haven fare on

indicators in six topical areas that profoundly shape their lives: employment and

earnings, economic security, education, health and well-being, crime and safety, and

political participation and leadership. The analysis of these indicators provides

information that can be used to assess womens and girls progress in achieving

rights and opportunities, to identify persisting barriers to gender and racial equality,

and to propose promising solutions for overcoming these barriers.

In focusing on these indicators, the report offers a glimpse into womens and girls

lives, highlighting their successes and contributions to local communities and the

economy as well as the complex challenges they face. A sketch of some basic

demographic information begins to paint a portrait of women and girls in New

Haven and their many contributions and challenges.

A sr(ro( s[ Hsora oad Cr| a dr Ho.ra

The female population in New Haven is, in many ways, quite diverse

1

. Among the

more than 68,000 women and girls who live in the city, comprising 53 percent of its

total population, blacks make up the largest share (37 percent), followed by whites

(32 percent) and Hispanics (23 percent; Figure 1.1). This is similar to the

composition of the male population in New Haven but significantly different from

the composition of the female population in Connecticut (U.S. Department of

Commerce 20082010a). In the state as a whole, more than seven in ten (72

percent) women and girls are white (Figure 1.2).

Figure 1.1

Percent of Female Residents by Race/Ethnicity, New Haven, 20082010

Note: Whites are identified as exclusive: white, not Hispanic. Persons whose ethnicity is identified

as Hispanic or Latino may be of any race. Other includes those who chose more than one race

category as well as those who chose a race other than white, black, Hispanic, or Asian.

Source: IWPR calculations based on American Community Survey data accessed through the

American Fact Finder (U.S. Department of Commerce 20082010a).

Figure 1.2.

Percent of Female Residents by Race/Ethnicity, Connecticut, 20082010

Note: Percentages do not add to 100 due to rounding.

Whites are identified as exclusive: white, not Hispanic. Persons whose ethnicity is identified as

Hispanic or Latino may be of any race. Other includes those who chose more than one race

category as well as those who chose a race other than white, black, Hispanic, or Asian.

Source: IWPR calculations based on American Community Survey data accessed through the

American Fact Finder (U.S. Department of Commerce 20082010a).

32%

37%

23%

6%

2%

White

Black

Hispanic

Asian

Other

72%

10%

13%

4%

2%

White

Black

Hispanic

Asian

Other

The Status of Women & Girls in New Haven, Connecticut

7

The population of women and girls in New Haven is also diverse in age. Of the

age groups shown in Figure 1.3, the largest share is aged 2544 (31 percent),

followed by those aged 1524 (22 percent; Appendix II, Table 1). In New Haven,

the age distribution of women and girls varies considerably by race and ethnicity,

although for every race and ethnic group the age range 2544 is the largest.

Among whites, a much larger proportion of women are 65 years and older (16

percent) than among blacks (nine percent), Hispanics (four percent), and Asians

(three percent). Hispanics are the youngest group (Figure 1.3).

Figure 1.3.

Age Distribution of Women and Girls by Race/Ethnicity, New Haven, 2008

2010

Note: Whites are identified as exclusive: white, not Hispanic. Persons whose ethnicity is

identified as Hispanic or Latino may be of any race.

Source: IWPR calculations based on American Community Survey data accessed through the

American Fact Finder (U.S. Department of Commerce 20082010a).

On average, the female population in New Haven is younger than the female

population in Connecticut as a whole (Appendix II, Table 1). The relatively

young character of the female population in New Haven compared with women

across the state may stem partly from the citys sizable student population due to

the presence of colleges and universities, as well as from higher birth rates among

New Havens residents. In 2009, the birth rate in New Haven (per 1,000) was 16.7,

compared with 11.0 for the state as a whole (Connecticut Department of Public

Health 2009a).

Women in New Haven are slightly older than men, on average, and less likely to

be married. Only about one in four women in the city (26 percent) aged 18 and

older is married, compared with more than three in ten men (32 percent)a

7%

21%

28%

11%

24%

18%

21%

31%

31%

29%

31% 44%

22%

23%

16%

11% 16%

9%

4%

3%

0%

10%

20%

30%

40%

50%

60%

70%

80%

90%

100%

White Black Hispanic Asian

65 Years and Older

45-64 Years

25-44 Years

15-24 Years

0-14 Years

8

The Status of Women & Girls in New Haven, Connecticut

2

This report uses the term immigrant to refer to individuals born outside the United States

who were not U.S. citizens at birth. As Singer, Wilson, and DeRenzis (2009) observe, this

includes legal permanent residents, naturalized citizens, refugees, asylum seekers, and

migrants who temporarily stay in the United States. It also includes some undocumented

immigrants, although this population is likely undercounted by the U.S. Census survey data.

The term native-born refers to individuals born in the United States or abroad of American

parents.

The Status of Women & Girls in New Haven, Connecticut

9

difference that may stem partly from the fact that women in New Haven

outnumber men. Both women and men in New Haven are much less likely than

women and men in Connecticut to be married. In the state, half of women (50

percent) and more than half of men aged 18 and older (56 percent) are married

(U.S. Department of Commerce 20082010b).

Half of all households in Connecticut are headed by a married couple, compared

with just one quarter of households in New Haven. New Haven has a

significantly higher proportion of households headed by single women either

with or without children (23 percent) than Connecticut as a whole (13 percent;

Appendix II, Table 2).

Dooroa( Hsora oad Cr| a dr Ho.ra: Darroa

(/r C(g P/ar oad O.rr(g

Over the last several decades, the rich diversity in New Haven has been enhanced

by growth in the citys immigrant population.

2

Between 1990 and 2010, the share

of New Havens population that is foreign-born doubled, increasing from eight

percent in 1990 to sixteen percent in 2010 (University of Virginia Library 2012

and U.S. Department of Commerce 2010). Between 2008 and 2010, slightly less

than half of all immigrants in the city (47 percent) were female (U.S. Department

of Commerce 20082010b).

Immigrant women and girls come to New Haven from all over the world. The

largest groups are from the West Indies and South America (20 percent and 16

percent, respectively), followed by Mexico (13 percent), China (11 percent), and

Central America, Canada, and Thailand (4 percent each; Figure 1.4). The pattern

of immigration differs somewhat in the United States as a whole, where the

largest group of female immigrants comes from Mexico (27 percent), followed by

South America, Central America, the West Indies (7 percent each), and China

and India (6 percent each; U.S. Department of Commerce 20082010b).

Figure 1.4.

Female Immigrants by Place of Birth, New Haven, 20082010

Source: IWPR analysis of 20082010 Integrated Public Use Microdata Series (IPUMS) American

Community Survey microdata (Ruggles, et al. 2010).

The demographic characteristics of immigrant women and girls in New Haven

differ in several ways from those of immigrant men and native-born women. A

larger proportion of immigrant women is aged 55 and older than immigrant men

(18 percent and 12 percent, respectively), a pattern that holds true for the citys

native-born population as well, although the difference in the proportion of older

women and men among the citys native-born residents is not as great (Appendix

II, Table 3). Immigrant women in New Haven are also less likely (44 percent) than

immigrant men (49 percent) but much more likely than native-born women (22

percent) to be married (Figure 1.5).

Figure 1.5.

Marital Status by Gender and Nativity, New Haven and Connecticut, 2008

2010

Note: For women and men aged 18 and older.

Source: IWPR analysis of 20082010 IPUMS American Community Survey microdata (Ruggles,

et al. 2010).

20%

16%

13%

11%

4%

4%

4%

3%

25% West Indies

South America

Mexico

China

Central America

Canada

Thailand

USSR/Russia

Other

44%

22%

59%

48% 49%

27%

64%

54%

0%

10%

20%

30%

40%

50%

60%

70%

Immigrants in New Haven Native-Born in New Haven Immigrants in Connecticut Native-Born in Connecticut

Women

Men

10

The Status of Women & Girls in New Haven, Connecticut

oa(a o (r/(rr Fa(arr [sr Hsora oad Cr| a

dr Ho.ra

As the nation moves out of a lingering economic recession, the New Haven

community needs to take steps to strengthen the economic security of women and

their families. National data show that although the media dubbed the Great

Recession of 20072009 a mancession, women suffered substantial losses and

have experienced an especially slow recovery, regaining jobs in the recessions

aftermath less quickly than men (Institute for Womens Policy Research 2012a).

Across the nation, many women have expressed concern for their ability to meet

their basic needs (Hayes and Hartmann 2011) and for their future economic

security (Hess, Hayes, and Hartmann 2011), making it imperative to explore the

opportunities to advance womens economic, social, and political status that exist

within communities like New Haven.

This report aims to help build economic security and overall well-being by

providing critical data on women and girls in New Haven, and by pointing to

places where additional data are needed to understand the health and well-being of

women and girls. We hope the information the report presents will assist

community leaders, policymakers, advocates, and others striving to enhance the

prospects of women and girls in the city and strengthen its many communities.

The Status of Women & Girls in New Haven, Connecticut

11

12

The Status of Women & Girls in New Haven, Connecticut

13

rg Fada

I In New Haven, as in virtually all cities and states in the United States,

women who work full-time, year-round have lower median annual

earnings than men. The gender wage gap in New Haven, however, is

smaller than in the United States as a whole. In New Haven, women earn

88 percent of mens earnings, compared with 78 percent in the nation.

This smaller earnings gap stems from two factors: mens earnings are

considerably lower in New Haven than in the nation as a whole, and

womens are slightly higher in the city compared with womens earnings

in the United States.

I Between 2008 and 2010, men in New Haven had a higher unemployment

rate (14 percent) than women (11 percent). White men had a higher

unemployment rate than white women (6 percent compared with 4

percent), and black men had a higher unemployment rate at 25 percent

(the highest rate of any gender-race/ethnic group) than black women (13

percent). Only among Hispanics did women (20 percent) have a higher

unemployment rate than men (14 percent). Among all women, Hispanic

and black women had much higher unemployment rates than white

women. Hispanic womens unemployment rate of 20 percent was the

highest and was five times higher than the unemployment rate for white

women (4 percent).

II.

Employment

and Earnings

3

Womens labor force participation includes the proportion of the adult (aged 16 and older)

female population who are employed or unemployed but looking for work. This includes

civilian, non-institutionalized women who are employed full-time or part-time, those who

work 15 hours or more per week as unpaid workers in a family business, and those who are

not currently working but are actively seeking employment (U.S. Department of Labor 2012a).

14

The Status of Women & Girls in New Haven, Connecticut

I In New Haven as elsewhere, there is a significant amount of sex

segregation in occupations. Women are twice as likely as men to work in

sales and office occupations, and men are about twice as likely as women

to work in production, transportation, and material moving occupations.

Men are also eleven times more likely than women to work in natural

resources, construction, and maintenance occupations.

Da(rsda(sa

Womens increased participation in the labor force marks an important change in

the national economy across the last six decades.

3

Nearly six in ten women now

work outside the home, compared with 34 percent of women in 1950 and 43

percent of women in 1970 (Fullerton 1999). Womens labor force participation in

New Haven reflects this national trend: 63 percent of women aged 16 and older

who live in the city are employed or looking for work (U.S. Department of

Commerce 20082010a).

The higher percentage of women in the workforce today points to the workforce

opportunities available to women and to the financial challenges women often

encounter as they strive to support themselves and their families. Womens earnings

are important to many families well-being and long-term economic security. Many

families rely on womens earnings to stay out of poverty and provide for old-age.

Despite womens increased labor force participation, women still do not enjoy

economic parity with men. In the nation as a whole, womens median earnings are

significantly less than the median earnings of men, a trend that is reflected in New

Haven, although to a lesser extent than nationwide. This section examines the

economic status of women in New Haven by considering their labor force

participation, the limitations placed on their work by disabilities, their earnings in

relation to mens, and their distribution across occupations and employment

sectors.

Hsora a (/r losr Fsrr

Between 2008 and 2010, more than six in ten women (63 percent) who were living

in New Haven were in the labor force, compared with 68 percent of men. Women

in New Haven are equally as likely as women in Connecticut, but more likely than

women in the United States as a whole, to be in the workforce (63 and 60 percent,

respectively), whereas men in New Haven are somewhat less likely than men in

Connecticut and nationwide to participate in the labor force (Figure 2.1).

Figure 2.1.

Percent of Women and Men in the Labor Force, 16 Years and Older, New

Haven, Connecticut, and United States, 20082010

Source: IWPR calculations based on American Community Survey data accessed through the

American Fact Finder (U.S. Department of Commerce 20082010a).

The labor force participation rate for women in New Haven is strong for all the

large race and ethnic groups. Two-thirds (66 percent) of black women are

employed or looking for work, compared with 62 percent of white women and 61

percent of Hispanic women (U.S. Department of Commerce 20082010a).

Workforce participation in New Haven, as elsewhere, varies across the life cycle. For

women, the highest participation occurs between the ages of 25 and 44 (79 percent;

U.S. Department of Commerce 20082010a). As women near retirement age, they are

less likely to work. Nonetheless, 62 percent of women aged 5564 and nearly one in

three women (32 percent) aged 6574 are in the workforce in New Haven (Figure 2.2).

Figure 2.2.

Labor Force Participation Among Women Aged 55 and Older in New

Haven, Connecticut, and United States, 20082010

Source: IWPR calculations based on American Community Survey data accessed through the

American Fact Finder (U.S. Department of Commerce 20082010a).

63% 63%

60%

68%

73%

70%

0%

10%

20%

30%

40%

50%

60%

70%

80%

New Haven Connecticut United States

Women

Men

The Status of Women & Girls in New Haven, Connecticut

15

62%

32%

2%

68%

28%

4%

60%

21%

4%

0%

10%

20%

30%

40%

50%

60%

70%

80%

5564 Years 6574 Years 75 Years and Older

New Haven

Connecticut

United States

losr Fsrr or(po(sa oad Oo|(g

While womens labor force participation has increased over the last six decades,

women with disabilities continue to face barriers that make it difficult to maintain

employment. In New Haven, a similar proportion of women (7.9 percent) and men

(8.5 percent) experience a disability that limits or prevents their participation in the

labor force. These percentages are similar in Connecticut, where 8.5 percent of

women and 8.0 percent of men experience a disability that limits or prevents their

work (Table 2.1). In the state as a whole, black women and men are more likely than

their white and Hispanic counterparts to have a disability that hinders their labor

force participation. Among both women and men, Hispanic men are the least likely

(6.6 percent) to have such a disability. Black women are the most likely (14.3

percent; Table 2.2).

Table 2.1.

Disability Limits or Prevents Work by Gender, New Haven and Connecticut,

20092011

Note: Includes women and men aged 15 and older.

Source: IWPR analysis of microdata from the 20092011 Current Population Survey Annual

Social and Economic Supplement (King, et al. 2010).

Table 2.2.

Disability Limits or Prevents Work by Gender and Race/Ethnicity,

Connecticut, 20092011

Notes: Includes women and men aged 15 and older.

Sample size is insufficient to reliably estimate the percent of Asians whose work is limited or

prevented by a disability.

Whites and blacks are identified as exclusive: white, not Hispanic; and black, not Hispanic.

Persons whose ethnicity is identified as Hispanic or Latino may be of any race.

Source: IWPR analysis of microdata from the 20092011 Current Population Survey Annual

Social and Economic Supplement (King, et al. 2010).

Disability Limits or Prevents Work

New Haven Connecticut

Women 7.9% 8.5%

Men 8.5% 8.0%

Overall 8.2% 8.3%

16

The Status of Women & Girls in New Haven, Connecticut

Disability Limits or Prevents Work

Women Men Overall

White 7.4% 8.1% 7.8%

Black 14.3% 12.5% 13.5%

Hispanic 13.4% 6.6% 9.9%

uarop|sgora(

Many women (and men) are looking for work in New Haven and are struggling to

find a job. Based on a three-year average (20082010) that encompasses the

recession and early stages of the recovery, the unemployment rate for both women

and men in the city is significantly higher than in Connecticut and the United

States as a whole. Eleven percent of women and 14 percent of men in New Haven

were unemployed, compared with 8 percent of women and 9 percent of men in

Connecticut and 8 percent of women and 10 percent of men nationwide (2008

2010 averages; Figure 2.3).

4

Last summer, Connecticuts General Assembly passed the first statewide

paid sick days law in the United States. This law represents an important

victory for workers in New Haven and the rest of Connecticut. Public

Law 11-52 guarantees full-time and part-time workers, in businesses with

50 or more employees, five paid sick days (or 40 hours) per year, usable

after 120 days of employment. Workers can use their paid sick time for

diagnoses or treatment of their own or their childs health condition or

for preventive care. They can also use it to address the effects of

domestic violence, sexual assault, or stalking (Miller and Williams 2010).

Paid sick days will significantly benefit New Havens working women.

Women are more likely to have caregiving responsibilities and to

sacrifice a day of pay to meet their families health care needs (Lovell

2003). Women also tend to be concentrated in occupations that are the

least likely to offer paid sick days, such as food preparation, personal

care and service, cleaning and maintenance, and sales and related

occupations (Williams, Drago, and Miller 2011). Because of the passage

of the paid sick days law in Connecticut, fewer women in New Haven will

have to choose between a day of pay and taking care of a sick child at

home.

New Law Introduces Earned Sick Days Policy

The Status of Women & Girls in New Haven, Connecticut

17

4

In the American Community Survey, the unemployed population includes all civilians not

living in institutionalized quarters, such as jails and nursing homes, who are aged 16 years and

older and who do not have a job but are actively looking for work (or waiting to be called back

to a job from which they have been laid off and are available to start a job). Students living

in dormitories who are at least 16 years of age and are actively looking for work are included.

Figure 2.3.

Unemployment Rates by Gender in New Haven, Connecticut, and United

States, 20082010

Note: For women and men aged 16 and older.

Source: IWPR calculations based on American Community Survey data accessed through the

American Fact Finder (U.S. Department of Commerce 20082010a).

Unemployment in New Haven is particularly high among blacks and Hispanics,

with black men and Hispanic women experiencing the highest unemployment rates

(25 percent and 20 percent, respectively) between 2008 and 2010. Only four

percent of white women and six percent of white men in New Haven were

unemployed during these years (Figure 2.4).

Figure 2.4.

Unemployment Rates by Gender and Race/Ethnicity, New Haven, 2008

2010

Notes: For women aged 16 and older.

Sample size is insufficient to reliably estimate the unemployment rate for Asians.

Whites are identified as exclusive: white, not Hispanic. Persons whose ethnicity is identified as

Hispanic or Latino may be of any race.

Source: IWPR calculations based on American Community Survey data accessed through the

American Fact Finder (U.S. Department of Commerce 20082010a).

8% 8%

14%

10%

11%

9%

0%

2%

4%

6%

8%

10%

12%

14%

16%

New Haven Connecticut United States

Women

Men

18

The Status of Women & Girls in New Haven, Connecticut

4%

13%

20%

6%

25%

14%

0%

5%

10%

15%

20%

25%

30%

White Black Hispanic

Women

Men

Eoraa oad (/r Cradrr Hor Cop

Despite their increased participation in the workforce, womens wages continue to

lag behind mens. Women in New Haven earn significantly less than men in the

city: womens median annual earnings

5

are $37,530, compared with $42,433 for

men. Put another way, women in New Haven earn nearly $5,000 less each year than

the typical man. Womens median annual earnings in New Haven are also much

less than womens ($45,379) and mens ($60,344) median annual earnings in

Connecticut, but slightly more than womens median annual earnings in the

United States overall ($36,142; Table 2.3).

6

This measure of earnings, however, includes only those who work full-time, year-

round. If the earnings of all women and men were included, the earnings gap

would be even larger. Nationally, women are twice as likely as men to work part-

time (U.S. Department of Labor 2010) and more likely to work for less than 50

weeks a year (U.S. Department of Commerce 2010). This disparity in working hours

is due to the unequal distribution of unpaid work in the family (Krantz-Kent 2009),

the lack of a public infrastructure to help families negotiate the demands of work

and family responsibilities (Society for Human Resource Management 2011), and,

in the low-wage segment of the economyparticularly in retail, hotels, and

restaurantsthe limited availability of full-time jobs (Kalleberg 2000; Lambert and

Henley 2009; Shaefer 2008). Research shows that part-time jobs pay lower hourly

wages, on average, than full-time jobs and are much less likely to come with

benefits (Kalleberg, Reskin, and Hudson 2000; Wenger 2001).

In New Haven, the median annual earnings of women who work full-time, year-

round vary considerably by race and ethnicity. White women have the highest

median annual earnings ($47,585), followed by Asian ($38,448) and black women

($35,977). Hispanic women have the lowest median annual earnings ($30,153). The

pattern differs slightly in Connecticut and the United States. In the state and the

nation as a whole, Asian women have the highest median annual earnings, followed

by white, black, and Hispanic women (Table 2.3).

While womens earnings in New Haven are lower than mens, the difference is not

as large as in the nation as a whole. In the United States between 2008 and 2010,

the ratio of female to male median annual earnings for full-time, year-round

workers was 78 percent. This means that women earned about 78 cents for every

The Status of Women & Girls in New Haven, Connecticut

19

5

The U.S. Census defines median earnings as the amount which divides the income

distribution into two equal groups, half having incomes above the median, half having

incomes below the median (U.S. Department of Commerce 2012a). Median annual earnings

here include only those who worked at least 50 weeks per year for 35 or more hours per

week.

6

While in New Haven men overall earn more than women, this pattern does not hold true

among the citys immigrant population. Immigrant women earn, on average, more than their

male counterparts ($36,460 compared with $32,000; Appendix II, Table 4). Earnings data,

however, do not distinguish between documented and undocumented immigrants and likely

do not fully account for the work performed in the informal economy.

Women in New

Haven earn

significantly less

than men in the city:

womens median

annual earnings are

$37,530, compared

with $42,433 for

men.

Note: For women and men aged 16 and older.

In 2010 inflation-adjusted dollars.

Whites are identified as exclusive: white, not Hispanic. Persons whose ethnicity is identified as Hispanic or Latino may be of any race.

Source: IWPR calculations based on American Community Survey data accessed through the American Fact Finder (U.S. Department of

Commerce 20082010a).

20

The Status of Women & Girls in New Haven, Connecticut

7

Because the data in this report are based on the 20082010 file of the American Community

Survey, they are not strictly comparable to IWPRs standard calculation of the gender wage

gap, which is based on the Current Population Survey (CPS). In 2010, the national earnings

gap based on the CPS was 23 percent (Hegewisch and Williams 2011).

8

Research has found that even after controlling for factors such as differences in work

experience, industry, and occupations, there is a gender wage gap that cannot be explained

and is potentially due to discrimination. One study estimates the unexplained percentage of

the wage gap among full-time workers in the United States to be 41 percent, and finds that

this residual gap includes discrimination in the labor market, although it may include other

factors as well (Blau and Kahn 2007).

New Haven Connecticut United States

Women Men Percent Women Men Percent Women Men Percent

All Races/Ethnicities $37,530 $42,433 88% $45,379 $60,344 75% $36,142 $46,376 78%

White $47,585 $53,631 89% $48,843 $65,361 75% $38,548 $51,395 75%

Black $35,977 $42,334 85% $38,572 $43,039 90% $32,197 $37,100 87%

Hispanic $30,153 $28,215 107% $31,374 $35,678 88% $26,847 $30,844 87%

Asian $38,448 $47,167 82% $49,457 $62,089 80% $42,116 $52,314 81%

Table 2.3.

Median Annual Earnings of Women and Men Employed Full-Time/Year-Round by Race/Ethnicity in New

dollar earned by men, representing a gender earnings gap of 22 percent.

7

In New

Haven during this time period, the female/male earnings ratio was 88 percent (it

was 75 percent for Connecticut; Table 2.3). Women in New Haven earned less than

men in all race and ethnic groups, with one exception: Hispanic women had higher

earnings than Hispanic men ($30,153 compared with $28,215). Nationally, and in

Connecticut as a whole, men earned more than women in every race and ethnic

group (Table 2.3).

8

The smaller wage gap in New Haven compared with the nation as a whole reflects

two factors: (1) mens earnings were comparatively lower, and (2) womens earnings

were comparatively higher than the national median annual earnings (but not

higher than earnings in Connecticut as a whole). Mens median annual earnings in

New Haven ($42,433) were lower than for men in the United States as a whole

($46,376) and significantly lower than for all men in Connecticut ($60,344). While

Connecticut is a state with some of the highest earnings for men in the nation (only

The Status of Women & Girls in New Haven, Connecticut

21

88%

89%

67%

56%

72%

75% 75%

59%

48%

76%

78%

75%

63%

52%

82%

0%

10%

20%

30%

40%

50%

60%

70%

80%

90%

100%

All Women's Earnings

as Percent of All Men's

White Women's

Earnings as Percent of

White Men's

Black Women's

Earnings as Percent of

White Men's

Hispanic Women's

Earnings as Percent of

White Men's

Asian Women's

Earnings as Percent of

White Men's

New Haven Connecticut United States

Figure 2.5.

Ratio of Women's to Men's Full-Time/Year-Round Median Annual Earnings by Race/Ethnicity in

New Haven, Connecticut, and United States, 20082010

Notes: Women and men aged 16 and older who work full-time, year-round.

The earnings of all women as a percent of the earnings of all men includes all races and ethnicities for both women and

men.

Whites are identified as exclusive: white, not Hispanic. Persons whose ethnicity is identified as Hispanic or Latino may be

of any race.

Source: IWPR calculations based on American Community Survey data accessed through the American Fact Finder (U.S.

Department of Commerce 20082010a).

Washington, DC, ranks higher nationally for mens earnings)

9

, it appears that a

relatively small proportion of New Haven residents hold high earning jobs.

Hispanic men, in particular, have below average earnings compared with Hispanic

men both in the nation and Connecticut. Asian men also earn less in New Haven

than in the state and the nation, although their earnings exceed the earnings for all

men in New Haven (Table 2.3). Unlike men in New Haven, women in the city

overall have slightly higher median annual earnings than women nationally, further

contributing to New Havens smaller wage gap.

10

Another way of examining the gender wage gap is to compare earnings for different

groups of women with the highest earning group, white men. Between 2008 and

9

See Institute for Womens Policy Research. 2012b. Overview: State-by-State Rankings and

Data on Indicators of Women's Social and Economic Status, 2010, available at

<http://www.iwpr.org/initiatives/states/2010-state-by-state-overview>.

10

Also, the large percentage of men of color in New Haven means that median earnings for

all men are lower in New Haven than in Connecticut or the United States (because men of

color have lower earnings, on average, than white men). The wages of women of color, while

generally lower than white womens, actually reflect smaller race/ethnic differences than

among men, explaining why mens median earnings in New Haven are more affected by the

large share of men of color than are womens median earnings.

22

The Status of Women & Girls in New Haven, Connecticut

2010, Hispanic women in New Haven earned 56 percent of the earnings of white

men in the city. In Connecticut and the United States, they earned only 48 percent

and 52 percent of white mens earnings, respectively. Black women earned 67

percent of white mens earnings in New Haven, 59 percent in Connecticut, and 63

percent in the United States. By comparison, for white women the wage ratio was

89 percent in New Haven and 75 percent in both Connecticut and the United

States. Asian women in New Haven earned 72 percent of the earnings of white

men, a lower earnings ratio than for Asian women in Connecticut (76 percent) and

the United States (82 percent; Figure 2.5).

While these gaps are large, for all groups of women except Asian women the gaps

between the earnings of women and white men in New Haven are smaller than

they are in either Connecticut or the United States as a whole. The explanation for

this pattern lies largely in the higher earnings of white, black, and Hispanic women

in New Haven relative to the earnings of comparable women in the nation as a

whole.

Dapo(sao| O(ra(sa

In New Haven, women tend to concentrate in several lower-paid broad

occupational groups. Twenty-eight percent of women work in sales and office

occupations, which have median annual earnings for women of $35,401. Nearly

one in four women (24 percent) in New Haven works in a service occupation, the

lowest paid occupational group for women (with median annual earnings of

$27,963; Figure 2.6 and Table 2.4).

The concentration of women in lower-paid occupational groups is especially

evident among Hispanic and black women. Hispanic and black women are much

more likely (28 percent and 33 percent, respectively) than white women (16

percent) to work in service occupations. In addition, 20 percent of Hispanic women

and eight percent of black women work in production, transportation, and material

moving occupations (the second lowest paid group of occupations for women),

compared with just three percent of white women (Appendix II, Table 5 and Table

2.4). The high proportion of Hispanic women working in these occupations makes

New Haven rather atypical compared with Connecticut and the nation as a whole,

where a much smaller proportion of Hispanic women work in such jobs (Appendix

II, Tables 6 and 7).

Few women in the city are employed in the highest paid occupational groups of

management, business, and financial occupations (seven percent); computer,

engineering, and science occupations (five percent); and healthcare practitioners

and technical occupations (seven percent; Figure 2.6; Table 2.4). More than one in

five women in New Haven, however, works in education, legal, community service,

arts, and media occupations, which have median annual earnings for women of

$39,940. This occupational group combines relatively well-paid jobs, such as

teachers or administrators in education, with very low-paid jobs such as teaching

assistants. A comparison of the median earnings for women and men in this group