Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

Organisational Climate

Enviado por

Dr-Rahat KhanDescrição original:

Direitos autorais

Formatos disponíveis

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Organisational Climate

Enviado por

Dr-Rahat KhanDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Introduction to Organisational Climate

Organisational climate is about the perceptions of the climate AND about absolute measures. Climate, as a metaphor is helpful - e.g. temperature is a measurable element of geographic climate, but it is not the absolute temperature that matters as much as human perception of it (is it cold, hot, or comfortable?). It is only after knowing what temperature means in terms of human comfort, that measurement of temperature becomes useful. Complicating perception is the probability that what may be too cool for one person may be too warm for another and just right for someone else. Similarly for organisations, the climate may be regarded in absolute terms and measured by instruments, but is felt differently by individuals. The absolute climate may suit one person and not another. What its like to work here or How I feel when I work here. Climate is worthwhile to understand and measure because there are organisational and human benefits a good climate, and powerful disadvantages of many kinds of bad climate.

In an increasingly competitive trading environment, there are compelling reasons to improve organisational performance. Typical targets for improvement programs are production quantity and quality, innovation, and creativity. But how do you do all that? We know that getting the entire organisational membership behind the performance push is important, but how do you create a climate that motivates people to think about how they can improve themselves and what they do for the organisations goals?

Organisational Change Whats been tried

It would seem bold to suggest that any one simple process, or change of process, could impact favourably on profit, employee turnover, EAP usage, sick days, absenteeism, commitment, innovation, creativity, performance and ultimately on share price, organisational esteem, executive kudos and so on. In fact, its not such a big ask. Its just that we are more familiar with narrowly focused fads and management programs, recognised by their three letter acronyms like MBO, JIT, QFD, CAT, TQC, QWL, TQP, CAM, SPC, VAM, MAP, TQM, MRP, CRM and BPR, and probably others. Research into their frequently poor ROI shows that they are usually applied in chunks and phases, and usually fail because they are introduced more as a way to improve efficiency than to spread strategic conversation focused on missions and visions.

Strategic Climate Planning & Alignment

Although organisational activities are theoretically conducted in an emotionless manner, and strategic plans are highly mechanistic in nature, there are at least two occurrences of 'below the line' interactions that need acknowledgement. Firstly, humans are doing the strategic planning, so feelings and emotions are an unavoidable (even if denied) and integral part of all group conversations . The climate that is 'felt' by participating executives will influence their behaviour during that conversation. In other words, climate influences strategic conversation. Secondly and conversely, the strategic decisions affect feelings and emotions of employees impacted by the decisions and thus influence the perceptual climate. So strategic conversation influences climate. Unfortunately, acknowledgement of that bi-directional interaction is absent from literature on strategic planning. This is in spite of recognition that much of what really goes on in an organisation takes place below the surface of daily behaviours, displayed in the form of conflicts, defensive behaviour, tensions and anxiety .

Climate and strategic planning

Before organisation-wide strategic thinking and conversation can occur, employees must 'feel' they are in a safe climate that encourages their understanding of , and involvement in, strategic conversation . It is even intuitively reasonable to expect a different climate report from within an organisation that merely 'permits' strategic thinking, to one that proactively encourages it from within a climate of psychological safety. In support of this approach is empirical evidence that climate and culture do indeed impact strategic thinking (Harris cited in . This line of argument provides support for the possibility of using climate planning intelligently - strategically - as a way to move strategic conversation throughout the organisation. The same argument supports acknowledging human behaviour within the resultant strategic plan - that is, the plan should acknowledge that it is dealing with humans. In summary, the links between strategic plans and emotions can be demonstrated in three ways. First there is the emotional involvement of participants to the process of developing strategic plans . Secondly, every strategic plan impacts people, and therefore their climate. The need to adjust plans to accommodate adverse impact on climate brings us to the need to deliberately set out to influence climate. It is akin to a 'climate impact study' for strategic plans. Finally, the previous two points prompt the suggestion that every strategic plan should acknowledge and account for climatic impact, and prepare the climate as necessary. A specific sub-strategy should conceivably be designed solely with emotional or climate goals. The strategic value of having a particular type of climate for the organisation in question may range from reducing turnover and absenteeism to enhancing organisational learning. Strategic climate planning and alignment (the subject of current research & development work by the author) therefore refers to an organisational system whereby the strategies that result from scenario planning are considered in the light of what kind of organisational climate do we need?' for the various scenarios. The design of organisational climate should address both external and internal environments. This question about climate then drives a new round of discussions by a similar spread of stakeholders to plan the climate that should suit the scenarios and resultant strategies. Its about learning how to adapt organisation climate to suit the current business climate. More importantly though, it is about learning how to create an organisational system that manages organisational climate - so that organisational climate can easily, quickly and painlessly align with the next business climate.

Climate and strategy

Some people describe organisations in terms of warfare (objectives, goals), and organisational processes in warlike terminology (strategic planning, tactics). Others, who

don't like the idea of having to go to war every day, prefer other more familial or paternal analogies. However, there is no avoiding the existence of competition between and within organisations, and that humans love competition - judging by the strong support for sporting activities. Humans also love challenge, judging by the recreational activities we choose. Interestingly, sporting groups also use the same war-like terminology - strategies and tactics. Perhaps, then, we can learn something by looking at military cases. For example, if a group of men is sent into the bush, what will happen? Did you just make an assumption? In your mind's eye were they fully trained military combat personnel on a mission. In fact, based on information you were given (a group of men is sent into the bush), not much of any value will happen. Outcomes might improve if they have goals - at least they will know why they are going. If they also have a plan, then it is more likely that the desired outcome will be delivered. It is even better if it is a strategic plan, with matching tactics and appropriate skills and abilities. Stratagem: artifice, trick(ery), device(s) for deceiving enemy. Strategic: Of, dictated by, serving the ends of, strategy; designed to disorganise the enemy's internal economy & to destroy morale. Strategy: Generalship, the art of war; management of an army in a campaign, art of so moving or disposing of troops, ships or aircraft as to impose upon the enemy the place & time & conditions for fighting preferred by oneself. Tactical: adroitly planning or planned in support of strategic operations. Tactics: art if disposing forces in actual contact with enemy, procedure calculated to gain some end, skilful device(s).

Let's examine this more closely. Consider two combat groups about to be sent into an aggressively hostile zone. One group is poorly trained, poorly prepared, and has vague goals. The other fully trained elite group has goals, objectives, strategies, contingencies and tactics all worked out. What will the climate be like within each group? Which group would you rather belong to? How does fear influence motivation? What about skills, and the clarity of how skills (group capability) match task (required capability)?

One can understand fear in a military engagement. What has been learned here about climate? What could the army do to create the most beneficial group climate?

If climate is about my perception - the way I feel about being here, what is felt at the indicidual level? To help explore this, consider two individuals in three situations. First they

are combatants in national championships for martial arts, with high chance of pain or injury, but each looking forward to the experience - nervous, some fear, but wouldn't miss it. Now they're together and facing a mountain. Person A sees all the places you can fall from. Person B sees all the handholds and footholds and assesses the various tracks for reaching the top. Now, put them on the beach looking at white-caps and rough water with high wind. Person A grins while preparing the windsurfer, and B can't imagine anything more frightening. The different approaches to situations may be due to skills and abilities, and also due in some way to a personal characteristic to see the challenge and excitement rather than the danger and fear. Increasing stimulus increases excitement - to a point - then it becomes increasing stress. A little bit of fear can be exhilarating. But there is a point beyond which the challenge is terrifying, and that point varies between individuals, and between situations. The fact that someone may have a low fear threshold for X does not mean a low threshold for Y. However, you can hardly have a one-person climate. But imagine a group of A's versus a group of B's at the mountain - then you have group climates. It also suggests how any one person contributes to group climate. The B people do not want any A's spoiling their group atmosphere, and vice versa. In other words, climate is of interest at personal, group, and organisational levelsSo climate is personal, and personal behaviours influence it, just as climate influences personal behaviour. It's a strong two-way relationship. So let's apply this to organisations and continue with the component - fear. We don't often think about fear as an issue in organisations, yet climate instruments consistently detect fear, or variables related to fear, among respondents. There are many things to fear in an organisation. Ask. Assuming there is fear, what does that do for the climate? How does that climate impact motivation? What will that do to efforts by members to deliver high performance aimed at corporate goals and strategies?

We have already suggested the importance to climate of having clear strategies, so are there clear goals and strategies in your organisation? By contrast, what chance for success is there for the organisation with opaque goals and a climate of fear or uncertainty? So let's assume that your organisation has clear goals and strategies. What happens now? If the organisation just rambles on as always, reactive and putting out fires while responding to ideas and whims, then having goals and strategies means nothing, and the climate will be one of confusion and lack of commitment. How can any member commit to an organisation that either doesn't know where it is going, or doesnt follow its own map? In having goals and strategies, it is as important to stop doing non-strategic acts as it is to start doing strategic ones. Too often, organisations spend resources on a project that was someone's idea, but it was never properly assessed for its strategic relevance, risks, or opportunity costs of time consumed. The people on that project know they are working on something that is merely a pet issue, and not really important in the scheme of things. How

do they feel? What are they learning about the organisation? How important a contribution do they feel they make? Do they feel good at the end of the day? What sort of climate are they feeling? Ideally, the organisation has a hierarchy of projects, all properly assessed for strategic importance and proportional resource demand. Assuming the organisation can do only so much, what are the criteria for starting or stopping a project? What provisions are there for compensating the greater psychological difficulty we have to exit a project than to start one? How does the organisation deal with the many vested but unimportant interests when egos become more important than the organisation's goals? From those questions: How can an organisation protect people from feeling devalued - because they know they are wasting time on an unimportant project? How can an organisation stop a project, while protecting the ego of those whose future ideas may be withheld if they are psychologically hurt as ideas fail to perform well enough or lose relevancy?

These are climate issues because they impact climate. What is the policy for outsourcing, and what internal resources are needed to administer any outsourced activity? This is another climate issue.

Clear procedures help clarify climate variables. Unclear procedures introduce climate 'noise' climate movements with unclear origins, and variations between silos that interpret policies differently. In other words - strategy and climate interconnect strongly.

How to assess organisational climate

If the organisation actually wants to understand and use climate, it will recognise that climate is a dynamic thing - and is too huge for for any one climate survey instrument to manage. When organisational climate is used correctly, only those attributes that are currently important, strategically and socially, need to be measured - and they may differ slightly each year. The organisation needs to learn about the cause-effect nature of organisational climate and how to manipulate the causes to have the desired impact on effect. Importantly, a climate survey must not be something done to an organisation. It must not be about HR or executives collecting data. Instead, it should be about members reporting their climate. The philosophical difference is huge, and will make a difference in how it is done - and the feeling of the organisational members towards participating. The sequence for a climate survey therefore becomes something like: Assess the desired climate based on strategic goals (usually missed out) Prepare members for survey (usually missed out) Assess the desired climate based on social view (usually missed out)

Design survey (often missed out - opting for a standard instrument) Prepare members for data collection (climate for data collection) (usually missed out) Collect data Analyse Interpret - with the aid of members (what does this mean?) (usually missed out) Remedial action plan with non-exec. members (locally) and executives (globally) Report - with the aid of members Bad Climate has been linked to: Turnover Stress Sickness Poor performance Error rate Wastage Accidents

Good Climate has been linked to desirable outcomes such as: Job satisfaction Confidence in management Affective commitment Intention to quit Emotional Exhaustion Faith in Organisational Performance

and to bad behaviours such as: Sabotage Absenteeism Go-slow Bullying

and to desirable behaviours such as: risk-taking (strategic), departure from the status quo, open communication, trust, operational freedom, and employee development -

"Employees have learned to distrust change programs."

A major common flaw is that they are inflicted and directed from the 'top down', but the additional effort required in execution is experienced bottom-up. In focusing on organisational economic / performance benefits, the plans ignore the very people who are required to make it work from the bottom up - the employees. Too little attention is paid to involving, motivating and inspiring people. The non-executive members see only what they risk losing - security, livelihood, opportunity, job satisfaction. To them changes mean more job losses, more work, longer hours, and more responsibility for the same or less money. In a response learned because nothing good for employees has ever happened following change, trust towards the organisation's executive level usually suffers.

A missing ingredient - 'what's in it for me'

The typical management program focuses on whats in it for the organisation, or the customer, or the shareholder. Such tunnel vision ignores the impact on the other stakeholder areas, especially employees. It is equally ineffective to emphasise the employees, and pander to their comfort wishes in the hope that it will translate into commitment and performance. Instead, we can learn from what we know about the psychology of motivation, and from successful change projects. We do know that most employees want to be valued, want to be proud to work 'here', want to contribute, want to look good and be appreciated, and want appropriate rewards for organisational gains from their contributions. People want to work, and will work hard even in harsh environments when they know why, and believe in why. Humans flourish in a fair and just relationship of give and take. It is rarely a money issue that triggers people to quit or under-perform but dissatisfaction about what its like to work here. To maintain high levels of commitment, innovation, creativity and performance, organisations should therefore expect to facilitate development of an organisational climate that is conducive to the desired behaviour. Unfortunately, organisational climate is currently an accident of everything the organisation is and does. How often does an executive member include the question 'what will this plan do to our climate?', or use a phrase something like heres the climate impact study? A deeper and strategic question would be 'If this plan is so important to us, what sort of climate will carry it through?'. Climate is not merely important, but strategically so. So, instead of ignoring it and letting it be an accident, how do we design, implement and maintain a suitable climate? And then how do we learn to improve those abilities to design, implement and maintain climate?

Why is climate important?

Organisational climate is essentially about what its like to work here. True to the climate metaphor, organisational climate is primarily about the perceptions of the climate rather than its absolute measures. While temperature is an important measure of geographic climate, it is not the temperature that is of interest, but our perception of it. What may be too cool for me may be too warm for you. To facilitate measurement and manipulation of organisational climate, researchers have dissected its characteristics and perceptions into categories such as the nature of interpersonal relationships, the nature of the hierarchy, the nature of work, and the focus of support and rewards. It is through those characteristics and perceptions that climate has a bi-directional relationship with everything the organisation is and does - it effects everything, and is effected by everything. For example: Organisational literature describes climates of crisis, trust, cooperation, calm, trust, distrust, entrepreneurialism, innovation, fear, respect, collective learning, openness and so on. Climates are also described as political, supportive, creative, strong, etc. For each climate there is an opposite: climate of calm vs crisis, and trust vs distrust etc. Climate relates strongly to performance measures.

Você também pode gostar

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeNo EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (5794)

- SalesDocumento1 páginaSalesDr-Rahat KhanAinda não há avaliações

- MMX 352G USB Modem User ManualDocumento26 páginasMMX 352G USB Modem User ManualDr-Rahat KhanAinda não há avaliações

- MMX 352G USB Modem User ManualDocumento26 páginasMMX 352G USB Modem User ManualDr-Rahat KhanAinda não há avaliações

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)No EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Nota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (98)

- SalesDocumento1 páginaSalesDr-Rahat KhanAinda não há avaliações

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceNo EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (895)

- Lupin Case StudyDocumento8 páginasLupin Case StudyDr-Rahat KhanAinda não há avaliações

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersNo EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (344)

- SalesDocumento1 páginaSalesDr-Rahat KhanAinda não há avaliações

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingNo EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (399)

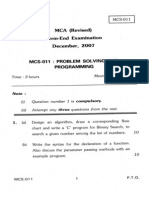

- MCS 011Documento4 páginasMCS 011Nitin NileshAinda não há avaliações

- Inferential StatisticsDocumento1 páginaInferential StatisticsDr-Rahat KhanAinda não há avaliações

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerNo EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (271)

- Effective Decision MakingDocumento3 páginasEffective Decision MakingDr-Rahat KhanAinda não há avaliações

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaNo EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (266)

- Competency MappingDocumento9 páginasCompetency MappingDr-Rahat KhanAinda não há avaliações

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItNo EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (838)

- Zahida ShabnamDocumento13 páginasZahida ShabnamDr-Rahat KhanAinda não há avaliações

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryNo EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (231)

- Emerging Trends in Corporate Governance PracticesDocumento9 páginasEmerging Trends in Corporate Governance PracticesDr-Rahat KhanAinda não há avaliações

- Zahida ShabnamDocumento9 páginasZahida ShabnamDr-Rahat KhanAinda não há avaliações

- Module 7 Weeks 14 15Documento9 páginasModule 7 Weeks 14 15Shīrêllë Êllézè Rīvâs SmïthAinda não há avaliações

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureNo EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (474)

- Words From The FilmDocumento4 páginasWords From The FilmRuslan HaidukAinda não há avaliações

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnNo EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (234)

- Elliot Kamilla - Literary Film Adaptation Form-Content DilemmaDocumento14 páginasElliot Kamilla - Literary Film Adaptation Form-Content DilemmaDavid SalazarAinda não há avaliações

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyNo EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (2259)

- 9709 w06 Ms 6Documento6 páginas9709 w06 Ms 6michael hengAinda não há avaliações

- Cost ContingenciesDocumento14 páginasCost ContingenciesbokocinoAinda não há avaliações

- A Journey To SomnathDocumento8 páginasA Journey To SomnathUrmi RavalAinda não há avaliações

- Villaroel Vs EstradaDocumento1 páginaVillaroel Vs EstradaLylo BesaresAinda não há avaliações

- Key Influence Factors For Ocean Freight Forwarders Selecting Container Shipping Lines Using The Revised Dematel ApproachDocumento12 páginasKey Influence Factors For Ocean Freight Forwarders Selecting Container Shipping Lines Using The Revised Dematel ApproachTanisha AgarwalAinda não há avaliações

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaNo EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (45)

- Principles and Methods of Effective TeachingDocumento5 páginasPrinciples and Methods of Effective TeachingerikaAinda não há avaliações

- A Case Study On College Assurance PlanDocumento10 páginasA Case Study On College Assurance PlanNikkaK.Ugsod50% (2)

- Developmental Stages WritingDocumento2 páginasDevelopmental Stages WritingEva Wong AlindayuAinda não há avaliações

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreNo EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (1090)

- Dynamic Behavior of Closed-Loop Control Systems: 10.1 Block Diagram RepresentationDocumento26 páginasDynamic Behavior of Closed-Loop Control Systems: 10.1 Block Diagram Representationratan_nitAinda não há avaliações

- Contract ManagementDocumento26 páginasContract ManagementGK TiwariAinda não há avaliações

- Final Research Proposal-1Documento17 páginasFinal Research Proposal-1saleem razaAinda não há avaliações

- (After The Reading of The Quote) : For The Entrance of The Philippine National Flag!Documento4 páginas(After The Reading of The Quote) : For The Entrance of The Philippine National Flag!JV DeeAinda não há avaliações

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)No EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Nota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (120)

- 1.introduction To Narratology. Topic 1 ColipcaDocumento21 páginas1.introduction To Narratology. Topic 1 ColipcaAnishoara CaldareAinda não há avaliações

- Turn Taking and InterruptingDocumento21 páginasTurn Taking and Interruptingsyah malengAinda não há avaliações

- Construction Quality Management 47 PDFDocumento47 páginasConstruction Quality Management 47 PDFCarl WilliamsAinda não há avaliações

- Financing The New VentureDocumento46 páginasFinancing The New VentureAnisha HarshAinda não há avaliações

- Daily Hora ChartDocumento2 páginasDaily Hora ChartkalanemiAinda não há avaliações

- "The Sacrament of Confirmation": The Liturgical Institute S Hillenbrand Distinguished LectureDocumento19 páginas"The Sacrament of Confirmation": The Liturgical Institute S Hillenbrand Distinguished LectureVenitoAinda não há avaliações

- Krautkrämer Ultrasonic Transducers: For Flaw Detection and SizingDocumento48 páginasKrautkrämer Ultrasonic Transducers: For Flaw Detection and SizingBahadır Tekin100% (1)

- Suitcase Lady Christie Mclaren ThesisDocumento7 páginasSuitcase Lady Christie Mclaren ThesisWriteMyPaperForMeCheapNewHaven100% (2)

- Chemical Engineering Science: N. Ratkovich, P.R. Berube, I. NopensDocumento15 páginasChemical Engineering Science: N. Ratkovich, P.R. Berube, I. Nopensvasumalhotra2001Ainda não há avaliações

- Internal Job Posting 1213 - Corp Fin HyderabadDocumento1 páginaInternal Job Posting 1213 - Corp Fin HyderabadKalanidhiAinda não há avaliações

- Degenesis Rebirth Edition - Interview With Marko DjurdjevicDocumento5 páginasDegenesis Rebirth Edition - Interview With Marko DjurdjevicfoxtroutAinda não há avaliações

- Sandy Ishikawa DiagramDocumento24 páginasSandy Ishikawa DiagramjammusandyAinda não há avaliações

- University of Mumbai: Bachelor of Management Studies (Finance) Semester VIDocumento73 páginasUniversity of Mumbai: Bachelor of Management Studies (Finance) Semester VIPranay ShettyAinda não há avaliações

- Spouses Benatiro V CuyosDocumento1 páginaSpouses Benatiro V CuyosAleli BucuAinda não há avaliações

- Application of Schiff Base Ligamd ComplexDocumento7 páginasApplication of Schiff Base Ligamd Complexrajbharaths1094Ainda não há avaliações