Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

ASEAN Economic Community Blueprint

Enviado por

Renzo R. GuintoDescrição original:

Direitos autorais

Formatos disponíveis

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

ASEAN Economic Community Blueprint

Enviado por

Renzo R. GuintoDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Trade and Health: The ASEAN Economic Community Blueprint

Ramon Lorenzo Luis R. Guinto University of the Philippines The Philippines is one of the founding members of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), a regional bloc of 10 countries in Southeast Asia. For almost a decade, member nations of ASEAN have been discussing the full realization of regional economic integration by year 2020. In 2007, the heads of state signed the ASEAN Economic Community Blueprint that lays the steps towards the envisioned single market and production base in the region. In the blueprint, there were listed five core elements of economic integration: (i) free flow of goods; (ii) free flow of services; (iii) free flow of investment; (iv) freer flow of capital; and (v) free flow of skilled labour. The fifth element, free flow of skilled labor, exerts a potentially huge burden on the already-dismal state of the health workforce in the region. A recent Lancet series on Southeast Asia reports that although there is no shortage of health workers in the region overall, many countries in southeast Asia suffer from problems in the health workforce related to shortages, skill mix imbalances, and maldistribution of skilled staff. In the Philippines, for example, while six out of ten Filipinos die without seeing a health professional, the country suffers from overproduction, maldistribution, high out-migration, nil inmigration, and low return migration of health professionals. Healthcare sector integration in the ASEAN According to the document ASEAN Roadmap for Integration of the Healthcare Sector, which is based on the overarching economic blueprint, ASEAN countries will aim to increase the ability of skilled labor meaning, health professionals to provide services across border. It was recommended that arrangements for visa and work permits will be standardized to ease mobility of health professionals in the region. A mutual recognition arrangement (MRA) for nursing services has actually been already signed in December 2006 this is the first attempt to develop a common set of professional standards or competencies in medical services. Work is underway for a similar MRA on medical practitioners. According to the MRA, host countries still retain the right to recognize foreign nursing qualifications; foreign-trained nurses are required to work with local nurses and will still need to apply for a license to practice from the competent authority of the host-country. Over time, the ASEAN Joint Coordinating Committee on Nursing that was established under the MRA could explore further acceptance of home market credential and experience as members become more familiar with each others regimes and practices and skills converge at a high level. Regional economic integration versus national public health? This plan, which is already under way, poses both advantages and disadvantages. Allowing greater mobility of health professionals expands the space of opportunities for the regions doctors and nurses who may want to take other pursuits that are not available in their home countries. Furthermore, enabling health workers to practice in neighboring countries may enhance potential for joint learning through formal education and research activities. However, the potential dangers of this proposal to national health security are quite alarming. Such increase in mobility may lead to internal/regional brain drain. Doctors and nurses who are unsatisfied by

work conditions and limited opportunities in poorer countries in ASEAN, let us say Myanmar, will opt to transfer to more prosperous Brunei to practice their profession and receive higher salaries. Spots left unoccupied by doctors in urban areas will be replaced by doctors from rural areas, therefore leaving poor rural areas underserved. The country will be left with health workers of lower quality, since the highly qualified ones have gone for greener pastures in the richer ASEAN states. On the other hand, doctors from technologically advanced Singapore will look for lucrative opportunities to expand practice in countries with a thriving upper and growing middle class like the Philippines, in order to bring new technology and knowledge. Filipinos then might consider seeing instead Singaporean doctors in Manila, thereby displacing local doctors. Tensions may arise between local and foreign doctors who are competing for patients/customers. Such liberalization in the flow of health workers within the region may aggravate existing shortages in poorer countries, worsen maldistributions by bringing more doctors to the cities and to richer countries, decrease quality of health workforce in countries with high out-migration, and ultimately deepen inequities in access to health workers. It seems that these negative consequences have not been considered when the economic integration plan was devised and applied in the health sector. Consideration of health in trade agreements In 2008, the WHO Commission on Social Determinants of Health stated in its report that governments should institutionalize consideration of health and health equity impact in national and international economic agreements and policy-making. I hope the architects of the ASEAN Economic Community Blueprint and its accompanying policies pertaining to regional healthcare sector integration heed this call.

Você também pode gostar

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)No EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Nota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (98)

- Solving Public Health Through Public HealthDocumento5 páginasSolving Public Health Through Public HealthRenzo R. GuintoAinda não há avaliações

- TOR For RA Migration HealthDocumento2 páginasTOR For RA Migration HealthRenzo R. GuintoAinda não há avaliações

- New Leaders For Health StatementDocumento3 páginasNew Leaders For Health StatementRenzo R. GuintoAinda não há avaliações

- Migrant Health in The PhilippinesDocumento6 páginasMigrant Health in The PhilippinesRenzo R. GuintoAinda não há avaliações

- Universal Health Coverage in 'One ASEAN': Are Migrants Included?Documento1 páginaUniversal Health Coverage in 'One ASEAN': Are Migrants Included?Renzo R. GuintoAinda não há avaliações

- IFMSA WHO Internship Application FormDocumento2 páginasIFMSA WHO Internship Application FormRenzo R. GuintoAinda não há avaliações

- IFMSA WHO Delegation Application Form RCM 2013Documento2 páginasIFMSA WHO Delegation Application Form RCM 2013Renzo R. GuintoAinda não há avaliações

- Manila Survival Guide For Interns PDFDocumento10 páginasManila Survival Guide For Interns PDFRenzo R. GuintoAinda não há avaliações

- Universal Health Care PreGA ProgramDocumento9 páginasUniversal Health Care PreGA ProgramRenzo R. GuintoAinda não há avaliações

- IFMSA WHO Internship Application FormDocumento2 páginasIFMSA WHO Internship Application FormRenzo R. GuintoAinda não há avaliações

- IFMSA WHO Internship Application FormDocumento2 páginasIFMSA WHO Internship Application FormRenzo R. GuintoAinda não há avaliações

- 1 66th WHA Provisional AgendaDocumento6 páginas1 66th WHA Provisional AgendaRenzo R. GuintoAinda não há avaliações

- IFMSA Internship Opportunity WHO ERM 2013 AprilDocumento2 páginasIFMSA Internship Opportunity WHO ERM 2013 AprilRenzo R. GuintoAinda não há avaliações

- ApplicationForm IFMSAExternalMeetingsDocumento3 páginasApplicationForm IFMSAExternalMeetingsRenzo R. GuintoAinda não há avaliações

- GHWA InternshipDocumento3 páginasGHWA InternshipRenzo R. GuintoAinda não há avaliações

- Concept Note - Youth Pre-World Health Assembly - 13.03.13-pw PDFDocumento16 páginasConcept Note - Youth Pre-World Health Assembly - 13.03.13-pw PDFInternational Pharmaceutical Students' Federation (IPSF)Ainda não há avaliações

- 5 Application Form-Youth-Pre-WHA and WHA For IFMSADocumento5 páginas5 Application Form-Youth-Pre-WHA and WHA For IFMSARenzo R. GuintoAinda não há avaliações

- Call For Applications - WHO Public Health and Environment Internship 2013Documento3 páginasCall For Applications - WHO Public Health and Environment Internship 2013Renzo R. GuintoAinda não há avaliações

- IFMSA Internship Opportunity WHO Patient SafetyDocumento2 páginasIFMSA Internship Opportunity WHO Patient SafetyRenzo R. GuintoAinda não há avaliações

- PSP Fact Sheet - May 2012Documento2 páginasPSP Fact Sheet - May 2012Renzo R. GuintoAinda não há avaliações

- IFMSA WHO Internship Application FormDocumento2 páginasIFMSA WHO Internship Application FormRenzo R. GuintoAinda não há avaliações

- WHO PHE Internship 2013 - Concept Note FINALDocumento4 páginasWHO PHE Internship 2013 - Concept Note FINALRenzo R. GuintoAinda não há avaliações

- Social Change Morong 43 PhilippinesDocumento2 páginasSocial Change Morong 43 PhilippinesRenzo R. GuintoAinda não há avaliações

- IFMSA LO WHO Plan of ActionDocumento13 páginasIFMSA LO WHO Plan of ActionRenzo R. GuintoAinda não há avaliações

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeNo EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (5795)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItNo EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceNo EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (895)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersNo EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (345)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingNo EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (400)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureNo EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryNo EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (231)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerNo EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (271)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaNo EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (266)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaNo EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (45)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnNo EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (234)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyNo EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (2259)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreNo EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)No EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Nota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (121)

- Pediatric Nurse Cover LetterDocumento5 páginasPediatric Nurse Cover Letterafjwoovfsmmgff100% (2)

- Eleonor Mateo LopezDocumento4 páginasEleonor Mateo LopezmikomapaulenAinda não há avaliações

- Full Download Test Bank For Maternal and Child Nursing Care 5th Edition by London Isbn 10 0134167228 Isbn 13 9780134167220 PDF Full ChapterDocumento6 páginasFull Download Test Bank For Maternal and Child Nursing Care 5th Edition by London Isbn 10 0134167228 Isbn 13 9780134167220 PDF Full Chaptertrigraph.loupingtaygv100% (21)

- Post Basic 2nd Year Master and ClinicalDocumento4 páginasPost Basic 2nd Year Master and ClinicalKavi rajput100% (1)

- Circulating Case Slip: Name of Student Student NumberDocumento12 páginasCirculating Case Slip: Name of Student Student NumberEugenio Roque Casaclang De Leon IiiAinda não há avaliações

- (Ebook PDF) Ethics and Issues in Contemporary Nursing 3Rd by Margaret A. BurkhardtDocumento41 páginas(Ebook PDF) Ethics and Issues in Contemporary Nursing 3Rd by Margaret A. Burkhardtdouglas.phillips23398% (42)

- Case ManagementDocumento2 páginasCase Managementapi-350503746Ainda não há avaliações

- Learning Plan Sem 3Documento4 páginasLearning Plan Sem 3api-596613382Ainda não há avaliações

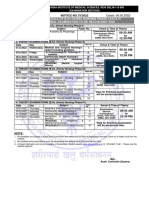

- Revised: Schedule of B.SC (Hons) Nursing Phase-I, Ii, Iii & Iv Professional Examination To Be Held in May 2022Documento1 páginaRevised: Schedule of B.SC (Hons) Nursing Phase-I, Ii, Iii & Iv Professional Examination To Be Held in May 2022sarath6872Ainda não há avaliações

- 2 - Hospital and It's OrganizationDocumento30 páginas2 - Hospital and It's OrganizationAbdul BasitAinda não há avaliações

- St. Paul University Philippines: School of Nursing and Allied Health SciencesDocumento13 páginasSt. Paul University Philippines: School of Nursing and Allied Health SciencesRachelle Ann DomingoAinda não há avaliações

- Fitrawati Arifuddin - How To Give An Oral Report To An RNDocumento9 páginasFitrawati Arifuddin - How To Give An Oral Report To An RNfitrawatiarifuddinAinda não há avaliações

- Exam For NursesDocumento15 páginasExam For Nursesaringkinking100% (2)

- 7th Grade State 2018Documento3 páginas7th Grade State 2018Izabela Uzunoska CrneskaAinda não há avaliações

- Roy's Adaptation ModelDocumento20 páginasRoy's Adaptation ModelKiana Vren Jermia100% (6)

- Kim Resume PDFDocumento1 páginaKim Resume PDFapi-548816548Ainda não há avaliações

- Community Health NursingDocumento40 páginasCommunity Health NursingSherlyn PedidaAinda não há avaliações

- A Descriptive Study To Assess The Level of Stress and Coping Strategies Adopted by 1st Year B.SC (N) StudentsDocumento6 páginasA Descriptive Study To Assess The Level of Stress and Coping Strategies Adopted by 1st Year B.SC (N) StudentsAnonymous izrFWiQAinda não há avaliações

- SituationDocumento32 páginasSituationEnzoyessaBilly ManauisAinda não há avaliações

- Pakalveedu-The Kollam Experience: Local InnovationDocumento6 páginasPakalveedu-The Kollam Experience: Local Innovationgion.nandAinda não há avaliações

- NUR-302 Nursing Theorist Betty Neuman WikiDocumento8 páginasNUR-302 Nursing Theorist Betty Neuman WikiCasey Ann Musice100% (5)

- Higher Education in KSA Changing Demand in Line With Vision 2030Documento11 páginasHigher Education in KSA Changing Demand in Line With Vision 2030vishalsontAinda não há avaliações

- Recent Advances On Patient Transferring DeviceDocumento13 páginasRecent Advances On Patient Transferring DeviceIsaac kadreeAinda não há avaliações

- Medical Devices and Ehealth SolutionsDocumento76 páginasMedical Devices and Ehealth SolutionsEliana Caceres TorricoAinda não há avaliações

- Completed Essential 3 E-Folio Nursing 402Documento4 páginasCompleted Essential 3 E-Folio Nursing 402api-374818694Ainda não há avaliações

- Hearts of Care Community Hospital Project ProposalDocumento33 páginasHearts of Care Community Hospital Project ProposalWALGEN TRADINGAinda não há avaliações

- B1 Prevalence of Bioethical Issues (Midterms)Documento12 páginasB1 Prevalence of Bioethical Issues (Midterms)Joan Cuh-ingAinda não há avaliações

- NCPDocumento6 páginasNCPgenevieve kryzleiAinda não há avaliações

- 2022021669Documento10 páginas2022021669Mahesh CheAinda não há avaliações

- Reviewer For P1Documento28 páginasReviewer For P1depedro.lorinel10Ainda não há avaliações