Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

Beyond Sticker Shock: What's Really Changed in Money in Politics in 2012?

Enviado por

Roosevelt InstituteDireitos autorais

Formatos disponíveis

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Beyond Sticker Shock: What's Really Changed in Money in Politics in 2012?

Enviado por

Roosevelt InstituteDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Beyond Sticker Shock: Whats Really Changed in Money in Politics in 2012?

Mark Schmi | The Roosevelt Institute Published: October 2nd, 2012

A RESEARCH AGENDA FOR JOURNALISTS, ACADEMICS, AND REFORMERS

That the role of money in American politics has changed in recent years cannot be doubted. Citizens United and other judicial decisions along the same line, the emergence of SuperPACs and 501(c)4 non-prots as campaign vehicles, the disappearance of rules governing coordination between campaigns and those groups, and the nal irrelevance of the presidential public nancing system have combined to return us to a climate roughly like that of the pre-Watergate era, when a few wealthy individuals, or in some cases corporations, could bankroll a candidate. The biggest dierence between the Nixon era and ours is that campaigns now cost 2,000 percent more. There are some things we know about this new environment. We know that in an era of unprecedented inequality of wealth and income, those who provide the means for politicians to be heard represent not just the 1 percent, but less than one-third of 1 percent: 0.026 percent of the population gives $200 or more to any federal candidate, but provide two-thirds of all campaign nancing. An even smaller share of the population maxes out or supports outside groups. Political inequality thus potentially reinforces economic inequality, in a dangerous and self-perpetuating cycle that, as Princeton political scientist Martin Gilens's recent book Auence and Inuence shows, diverts public policy from the public's views. We also know that when a single source supports a campaign with millions of dollars, it creates a dependent relationship between an elected ocial and the donor, which inevitably distorts decision-making maybe just a li le, maybe a lot. But there is more to the new world of money in politics than intimidating numbers and concerns about corruption and dependency. To fully understand or address the role of money in politics, we need to understand how money really works in politics, what its eects are, and what has changed in this cycle other than the top-line numbers. Here are some of the questions to consider, especially as full data on this election comes in a er November, looking at both what's happened and its implications for policy:

HAS MONEY AFFECTED COMPETITION?

Money can aect political competition in two ways: through scarcity (when candidates don't have enough money to compete) and through abundance (when some have overwhelming amounts). In the current climate, money is hardly scarce on any side, and that has an eect on competition. During the GOP presidential primaries, SuperPAC money kept candidacies alive that, in the past, would have expired for lack of money. While this created situations of total dependency for candidates on a single donor, it also led to competition that was absent in past presidential primary ba les where viable candidates ran out of money. Did the same occur at other levels? Were more congressional candidates able to reach the threshold to run competitive races? Or did huge blasts of outside spending wipe out potentially viable candidacies, in primaries or the general election? One measure will be, how many non-incumbents are able to reach the basic threshold for competitiveness?

DOES MONEY AFFECT POLARIZATION?

Many SuperPAC and other outside-money donors, especially those on the right, appear to be more ideologically focused than donors in the past, such as the so -money donors of the 1990s. And industries and corporations that have traditionally spread their bets across the parties appear from Center for Responsive Politics data (which includes employee contributions) to be moving toward stronger partisan alliances in 2012.

About the Roosevelt Institute The Roosevelt Institute is a nonprot organization carrying forward the Roosevelt legacy and forging a New Deal for the 21st century by developing innovative policy ideas, bold leadership, and a strategy to restore Americas promise of opportunity for all.For more information visit us at www.rooseveltinstitute.org or nd us on Facebook and Twi er.

Copyright 2012, the Roosevelt Institute. All rights reserved.

The views and opinions expressed in this paper are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the views of the Roosevelt Institute, its ocers, or its directors.

Finally, evidence shows that outside groups tend to run more negative ads than candidates themselves, potentially locking the candidates into positions that are dicult to step back from. Is this money making party positions more intractable, and thus exacerbating the structural polarization of politics?

ARE THERE DOWNSIDES TO SUPERPACS AND OTHER OUTSIDE-MONEY VEHICLES?

In the recent past, there were signicant reasons for campaigns to prefer to avoid moving money through outside organizations, since it meant giving up a considerable amount of control of their message. But with the de facto disappearance of rules about coordination between campaigns and outside commi ees (many SuperPACs are dedicated not to a cause but to a candidate, and are controlled by longtime staers to the candidate), there is no longer much reason for candidates to avoid SuperPACs or other outside vehicles. But two downsides remain: Broadcast stations are free to reject ads by outside groups that they consider false or misleading, and, more importantly, outside groups do not receive the lowest unit rate guarantee. A recent ProPublica report indicated that this second factor had all but wiped out the Romney campaign's early fundraising advantage over President Obama's campaign: Because more of Romney's ad buys were through outside groups, they were paying six times more for the same advertising time.

DO BROADCAST ADS MATTER AS MUCH AS THEY USED TO?

Radio and television advertising is still by far the largest cost in campaigns above the local level, and ads remain the only way to reach voters who aren't rmly commi ed and who don't seek out political information in newspapers or online. Reform eorts, such as the electioneering communications provisions of BCRA that were at issue in Citizens United, have focused primarily on broadcast media not only by bringing ads intended to inuence the election into the regulated zone, but also by ensuring aordable or free time for candidates. As the share of the voting electorate that is genuinely wavering shrinks to an estimated 3 to 5 percent, especially for high-prole races such as the presidency, the emphasis shi s to turnout and mobilization of the base (or pu ing obstacles, such as voter ID laws, in the way of turnout). The more consequential outside money, then, may involve not the be er-known SuperPACs, but groups involved in turnout and mobilization, or in discouraging voting, such as the group called True the Vote.

DO SMALL DONORS STILL MATTER?

Beginning in 2004, and partly facilitated by the Internet, small donors became a more signicant force in political campaigns, and campaigns put more eort into seeking small donors. This made small-donor reforms, which rely less on limits and more on incentives for small contributions, a ractive to many observers, notably the four political scientists who authored the paper, Reform in the Age of Networked Campaigns in 2010; law professor Spencer Overton in his recent article, The Participation Interest; and the congressional authors of the recently introduced Empowering Citizens Act. These reforms would use tax credits, matching funds, and other incentives, based on successful programs such as New York City's matching system, to motivate small donors to give and encourage campaigns to go a er them. Designed well, such as in Minnesota's system of an instantly refundable tax credit (now defunded, unfortunately), they can be, in eect, a voucher system in which every citizen will have the ability to make a small contribution and those contributions will ma er. Recent evidence from the Campaign Finance Institute suggests that even in an era of very big money, small donors do still ma er at least to the Obama campaign, which continued to get 34 percent of its support from 2

HAVE CORPORATIONS CHANGED THEIR BEHAVIOR?

The post-Citizens United scenario in which large corporations pour millions into eorts to unseat some politicians and boost others has not come to pass. With a few exceptions, and granted that we have limited information on many spending vehicles, corporations and especially publicly held corporations have not been the main contributors to SuperPACs. But have corporations changed their behavior in other ways, perhaps more in response to the sense that anything goes rather than the specic legal changes brought about by Citizens United? For example, have they used 501c(4) vehicles to move more partisan funding, while keeping the veneer of bipartisanship in their disclosed funding? Have they increased their communications with their own employees about politics, such as through internal websites a trend that began in 2008?

Copyright 2012, the Roosevelt Institute. All rights reserved. WWW.ROOSEVELTINSTITUTE.ORG

donors who gave less than $200. A er the election, we'll want to see how many congressional candidates built a viable base of small donors.

CAN SMALL-DONOR REFORMS WITHSTAND OUTSIDE MONEY?

A central debate among reformers is whether Citizens United and the decision known as McComish v. Benne , which threw out part of Arizona's public nancing system, will have to be reversed, by the Supreme Court or by constitutional amendment, in order for smalldonor public nancing to work. McComish prohibited systems that gave candidates under a ack by outside groups additional public funds. Arizona's system seems to have survived without this provision, in that all statewide candidates are participating in the public nancing system. A closer look at other state and municipal public nancing systems as they evolve will help determine whether they can work even within the Court's current framework, but all indications are that they can.

Recent polling by Greenberg Quinlan Rosner concluded that money in politics is not a distraction from the economy, it is the economy, and that voters would support candidates who seize the issue of reform and support small-donor matching programs and public nancing. We are entering a new era of political salience for the issue. But will the new public passion about the issue, particularly among those who connect it to economic inequality, make it more dicult to build the cross-partisan bridges that traditionally have made reform possible?

____________________________________________ MARK SCHMITT is a Senior Fellow at the Roosevelt

Institute, where he works on issues including money in politics and progressive taxation. He is a columnist for The New Republic and former editor of The American Prospect.

IS REFORM FINISHED AS A BIPARTISAN PROJECT?

Before there was McCain-Feingold, there was Goldwater-Boren; campaign nance reform has always been a bipartisan and cross-ideological project, in the states as well as at the federal level. In the 2000s, conservatives moved toward advocating deregulation coupled with full and instant disclosure as an alternative to limits, but in the current Congress, there are no Republican supporters of even the DISCLOSE Act. However, Senator John Cornyn recently suggested that he was open to some form of campaign reform, and Mi Romney even suggested banning contributions but only from teachers unions. Especially a er an electoral defeat, and the revelation that a SuperPAC advantage doesn't automatically translate into electoral victory, it's possible that the political alignments will be shaken again.

DOES THE PUBLIC CARE?

For decades, the role of money in politics has been at best a secondary issue for most voters, and largely an elite concern. In this cycle, however, there has been far more a ention paid in the media to money and stories about SuperPACs and big donors, and that news has connected to an overall concern about economic inequality that has engaged the public as never before even if much of the energy is focused on overturning Citizens United.

Copyright 2012, the Roosevelt Institute. All rights reserved. WWW.ROOSEVELTINSTITUTE.ORG

Você também pode gostar

- Profit Over Patients: How The Rules of Our Economy Encourage The Pharmaceutical Industry's Extractive BehaviorDocumento23 páginasProfit Over Patients: How The Rules of Our Economy Encourage The Pharmaceutical Industry's Extractive BehaviorRoosevelt InstituteAinda não há avaliações

- Off-Balance: Five Strategies For A Judiciary That Supports DemocracyDocumento45 páginasOff-Balance: Five Strategies For A Judiciary That Supports DemocracyRoosevelt InstituteAinda não há avaliações

- Ending Shareholder Primacy in Corporate GovernanceDocumento36 páginasEnding Shareholder Primacy in Corporate GovernanceRoosevelt InstituteAinda não há avaliações

- A Proposal To Enhance Antitrust Protection Against Labor Market MonopsonyDocumento23 páginasA Proposal To Enhance Antitrust Protection Against Labor Market MonopsonyRoosevelt InstituteAinda não há avaliações

- New Rules For Big Tech: A Conversation For ChangeDocumento5 páginasNew Rules For Big Tech: A Conversation For ChangeRoosevelt InstituteAinda não há avaliações

- The Unsound Theory Behind The Consumer (And Total) Welfare Goal in AntitrustDocumento49 páginasThe Unsound Theory Behind The Consumer (And Total) Welfare Goal in AntitrustRoosevelt InstituteAinda não há avaliações

- Unstacking The Deck: A New Agenda To Tame Corruption in WashingtonDocumento41 páginasUnstacking The Deck: A New Agenda To Tame Corruption in WashingtonRoosevelt InstituteAinda não há avaliações

- The Labor Market Impact of The Proposed Sprint-TMobile MergerDocumento31 páginasThe Labor Market Impact of The Proposed Sprint-TMobile MergerRoosevelt InstituteAinda não há avaliações

- Competition and Consumer Protection in The 21st CenturyDocumento26 páginasCompetition and Consumer Protection in The 21st CenturyRoosevelt InstituteAinda não há avaliações

- Left Behind: Snapshots From The 21 ST Century Labor MarketDocumento56 páginasLeft Behind: Snapshots From The 21 ST Century Labor MarketRoosevelt Institute100% (1)

- Towards Accountable Capitalism': Remaking Corporate Law Through Stakeholder GovernanceDocumento17 páginasTowards Accountable Capitalism': Remaking Corporate Law Through Stakeholder GovernanceRoosevelt Institute100% (1)

- The Effective Competition Standard: A New Standard For AntitrustDocumento59 páginasThe Effective Competition Standard: A New Standard For AntitrustRoosevelt InstituteAinda não há avaliações

- Seven Strategies To Rebuild Worker PowerDocumento59 páginasSeven Strategies To Rebuild Worker PowerRoosevelt InstituteAinda não há avaliações

- The Year of The Woman, AgainDocumento3 páginasThe Year of The Woman, AgainRoosevelt InstituteAinda não há avaliações

- Who Pays? How Industry Insiders Rig The Student Loan System-And How To Stop ItDocumento19 páginasWho Pays? How Industry Insiders Rig The Student Loan System-And How To Stop ItRoosevelt InstituteAinda não há avaliações

- Beyond The Budget: How The Tax Cuts and Jobs Act Increases Inequality and Exacerbates Our High-Profit, Low-Wage EconomyDocumento10 páginasBeyond The Budget: How The Tax Cuts and Jobs Act Increases Inequality and Exacerbates Our High-Profit, Low-Wage EconomyRoosevelt InstituteAinda não há avaliações

- Rebuilding Worker Voices in Today's EconomyDocumento47 páginasRebuilding Worker Voices in Today's EconomyRoosevelt InstituteAinda não há avaliações

- 10 Years After The Financial CrisisDocumento24 páginas10 Years After The Financial CrisisRoosevelt Institute100% (3)

- The United States Has A Market Concentration ProblemDocumento14 páginasThe United States Has A Market Concentration ProblemRoosevelt InstituteAinda não há avaliações

- Public Banking Option As A Mode of Regulation For Household Financial Services in The United StatesDocumento33 páginasPublic Banking Option As A Mode of Regulation For Household Financial Services in The United StatesRoosevelt Institute100% (1)

- Thinking Outside The (Patent) Box: An Intellectual Property Approach To Combating International Tax AvoidanceDocumento28 páginasThinking Outside The (Patent) Box: An Intellectual Property Approach To Combating International Tax AvoidanceRoosevelt InstituteAinda não há avaliações

- Who Are The Shareholders?Documento24 páginasWho Are The Shareholders?Roosevelt InstituteAinda não há avaliações

- Don't Fear The Robots: Why Automation Doesn't Mean The End of WorkDocumento34 páginasDon't Fear The Robots: Why Automation Doesn't Mean The End of WorkRoosevelt InstituteAinda não há avaliações

- Market Concentration and The Importance of Properly Defined MarketsDocumento9 páginasMarket Concentration and The Importance of Properly Defined MarketsRoosevelt InstituteAinda não há avaliações

- Remembering Rural: Shaping Connected and Automated Vehicle Technology in North CarolinaDocumento19 páginasRemembering Rural: Shaping Connected and Automated Vehicle Technology in North CarolinaRoosevelt InstituteAinda não há avaliações

- Airline Consolidation, Merger Retrospectives, and Oil Price Pass-ThroughDocumento33 páginasAirline Consolidation, Merger Retrospectives, and Oil Price Pass-ThroughRoosevelt InstituteAinda não há avaliações

- Hidden Rules of Race Are Embedded in The New Tax LawDocumento16 páginasHidden Rules of Race Are Embedded in The New Tax LawRoosevelt Institute100% (1)

- Making The Case: How Ending Walmart's Stock Buyback Program Would Help To Fix Our High-Profit, Low-Wage EconomyDocumento9 páginasMaking The Case: How Ending Walmart's Stock Buyback Program Would Help To Fix Our High-Profit, Low-Wage EconomyRoosevelt InstituteAinda não há avaliações

- The Many Hands Food Cooperative: Ending Food Deserts and Building Sustainable Communities Through Asset-Ownership and Community EmpowermentDocumento18 páginasThe Many Hands Food Cooperative: Ending Food Deserts and Building Sustainable Communities Through Asset-Ownership and Community EmpowermentRoosevelt InstituteAinda não há avaliações

- A Missing Link: The Role of Antitrust Law in Rectifying Employer Power in Our High-Profit, Low-Wage EconomyDocumento13 páginasA Missing Link: The Role of Antitrust Law in Rectifying Employer Power in Our High-Profit, Low-Wage EconomyRoosevelt InstituteAinda não há avaliações

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeNo EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (5794)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingNo EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (400)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceNo EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (895)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)No EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Nota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (98)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerNo EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (271)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryNo EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (231)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItNo EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (838)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureNo EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (474)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaNo EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (266)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaNo EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (45)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnNo EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (234)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyNo EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (2259)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreNo EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (1090)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersNo EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (344)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)No EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Nota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (121)

- Chapter 13 IdsDocumento8 páginasChapter 13 Idsapi-235757939Ainda não há avaliações

- 7re - (Groundswellgroup) FWD - Obama Takes Total Control of Elections - Google GroupsDocumento3 páginas7re - (Groundswellgroup) FWD - Obama Takes Total Control of Elections - Google GroupsBreitbart UnmaskedAinda não há avaliações

- Commissioner Rebecca Benally Speech On Bears Ears, Edits by Sutherland InstituteDocumento4 páginasCommissioner Rebecca Benally Speech On Bears Ears, Edits by Sutherland InstituteThe Salt Lake TribuneAinda não há avaliações

- Apush Chapter 6 VocabDocumento2 páginasApush Chapter 6 VocabSarahAinda não há avaliações

- Lesson 2 The Vice President and The First LadyDocumento8 páginasLesson 2 The Vice President and The First LadyEsther EnriquezAinda não há avaliações

- Instant Download Hotel Operations Management 3rd Edition Hayes Solutions Manual PDF Full ChapterDocumento32 páginasInstant Download Hotel Operations Management 3rd Edition Hayes Solutions Manual PDF Full Chapterfuturelydotardly1ivv100% (10)

- Plaintiff's First Amended Petition and Request For DisclosureDocumento7 páginasPlaintiff's First Amended Petition and Request For DisclosureThe Bench WireAinda não há avaliações

- E-Town Dems Complaint 2Documento2 páginasE-Town Dems Complaint 2Alex GeliAinda não há avaliações

- Clinton AndersonDocumento1 páginaClinton AndersonJorge MonteroAinda não há avaliações

- Instant Download Enduring Vision A History of The American People 8th Edition Boyer Solutions Manual PDF Full ChapterDocumento32 páginasInstant Download Enduring Vision A History of The American People 8th Edition Boyer Solutions Manual PDF Full Chapterdrtonyberrykzqemfsabg100% (8)

- Brians Preview AG Issues BookDocumento369 páginasBrians Preview AG Issues BookcqpresscustomAinda não há avaliações

- Instant Download Principles of Contemporary Marketing 14th Edition Kurtz Test Bank PDF Full ChapterDocumento32 páginasInstant Download Principles of Contemporary Marketing 14th Edition Kurtz Test Bank PDF Full Chapterdandyizemanuree9nn2y100% (6)

- MO Senate GOP Primary MemoDocumento3 páginasMO Senate GOP Primary MemoBreitbart NewsAinda não há avaliações

- Malone POL 296N Lecture 1Documento20 páginasMalone POL 296N Lecture 1cmalone410Ainda não há avaliações

- Sesi 7 Tugas 3Documento3 páginasSesi 7 Tugas 3teguh AWAinda não há avaliações

- William JDocumento2 páginasWilliam JFactPaloozaAinda não há avaliações

- Breakfast For Adam SmithDocumento1 páginaBreakfast For Adam SmithSunlight FoundationAinda não há avaliações

- Central Intelligence Agency - HistoryDocumento2 páginasCentral Intelligence Agency - Historyapi-241177893Ainda não há avaliações

- Sources For Brown V Board BibliographyDocumento6 páginasSources For Brown V Board Bibliographyapi-255671918Ainda não há avaliações

- Linda Greenhouse and Tony Picadio On Gun RightsDocumento3 páginasLinda Greenhouse and Tony Picadio On Gun RightsDon ResnikoffAinda não há avaliações

- Second Impeachment Trial of Donald Trump - Wikipedia - 1612944177787Documento134 páginasSecond Impeachment Trial of Donald Trump - Wikipedia - 1612944177787Baguma danielAinda não há avaliações

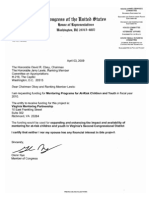

- Earmark RequestDocumento1 páginaEarmark RequestdjsunlightAinda não há avaliações

- NotforDistribution PMPExamFacilitatedStudy5thEdDocumento2 páginasNotforDistribution PMPExamFacilitatedStudy5thEdAli AsadAinda não há avaliações

- Milwaukee Family Court Judge Orders My Ex-Wife Carol Spizzirri To Submit To A Psychological Evaluation (Spizzirri v. Pratt, Case #656-244, 1/15/85)Documento30 páginasMilwaukee Family Court Judge Orders My Ex-Wife Carol Spizzirri To Submit To A Psychological Evaluation (Spizzirri v. Pratt, Case #656-244, 1/15/85)Gordon T. PrattAinda não há avaliações

- APUSH Notes 11-12Documento6 páginasAPUSH Notes 11-12SimoneMicheleAinda não há avaliações

- Democratic Party (United States)Documento44 páginasDemocratic Party (United States)Karl GustavAinda não há avaliações

- 2 Views of Forgotten ManDocumento2 páginas2 Views of Forgotten Manapi-260900099Ainda não há avaliações

- Executive Order D 78 89 California Governor 1989Documento3 páginasExecutive Order D 78 89 California Governor 1989Iowa Liberty Alliance100% (1)

- Eric Coomer v. Donald J. Trump For President Inc.Documento7 páginasEric Coomer v. Donald J. Trump For President Inc.Michael_Roberts2019Ainda não há avaliações

- Registration by BROWNSTEIN HYATT FARBER SCHRECK, LLP To Lobby For FirstService Residential Realty, Inc. (300314104)Documento2 páginasRegistration by BROWNSTEIN HYATT FARBER SCHRECK, LLP To Lobby For FirstService Residential Realty, Inc. (300314104)Sunlight FoundationAinda não há avaliações