Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

Leon Trotsky

Enviado por

Carl RollysonDescrição original:

Direitos autorais

Formatos disponíveis

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Leon Trotsky

Enviado por

Carl RollysonDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Leon Trotsky was both an intellectual and a man of action.

One of the charismati c leaders of the Russian RevolutionLenin said there was no better Bolshevikhe crea ted the Red Army through virtually an act of will and led it to victory in the 1 918-20 civil war. But he was also a mesmerizing dissenter, sent by Stalin into e xile in 1927 and then murdered in Mexico by one of Stalin's agents in 1940. Trotsky was Jewishborn Lev Davidovich Bronstein in 1879and it is as such that he i s treated in Joshua Rubenstein's brief biography, part of Yale University Press' s Jewish Lives series. Trotsky said that his ethnic background had not the sligh test influence on his life. But no one inquiring into his origins can ignore wha t it meant to be a Jew in a Russia permeated with anti-Semitism or can suppose t hat because Trotsky opposed Zionismor, indeed, any movement or policy that favore d Jewshe was unaffected when many of his actions were attributed to his Jewishnes s. Isaac Deutscher, the author of the classic biography of Trotsky (three volumes, published between 1954 and 1963), largely took his subject at his word, noting o nly those instances when Trotsky himself raised the issue of his Jewishness. Tro tsky rejected, for example, Lenin's wish to appoint him commissar of home affair s in 1917, pointing out, according to Deutscher, that counter-revolutionaries wo uld "whip up anti-Semitic feeling and turn it against the Bolsheviks." After Len in died in 1924, Trotsky appealed to Nicolai Bukharin, a fellow Politburo member , to speak out against the anti-Semitic Party members working for Stalin who had begun "hinting" (Deutscher's word) that Trotsky had better give way to "native and genuine Russian socialism." Otherwise, Deutscher is as silent as his subject about the nexus between "Trotsky and the Jews." That is the title of a chapter in Robert Service's "Trotsky" (2009), which provi des helpful background. Trotsky was not a so-called self-hating Jew. He often li ved among Jews in Russia and abroad, but he described himself as an "internation alist," which meant that he wanted nothing whatever to do with specifically Jewi sh causes. He neither favored nor discriminated against Jews and spoke up for th em only in terms of his defense of all minorities suffering discrimination. Mr. Service, however, clarifies an aspect of Trotsky's belief and behavior that bears directly on what Mr. Rubenstein calls Trotsky's "curiously passive" stance during the period after Lenin's death, when Stalin was busily lining up allies and consolidating his hold on power. Mr. Service observes: "Trotsky continued to believe that his own prominence in government, party and army did practical dam age to the revolutionary cause." Surprisingly, Mr. Rubenstein, who is highly cri tical of Mr. Service's biography for its "gratuitous criticism of Trotsky's char acter and personality" and its failure "to understand the full complexity of Tro tsky's relationship to his Jewish origin," does less in a whole book than Mr. Se rvice did in that single sentence to explain why it waswith the fate of a revolut ion in his hands, with at least the chance to outwit and even outgun StalinTrotsk y hesitated and so lost. (He also underestimated his opponent, thinking that bec ause Stalin had neither his intellect nor experience, he would fail.) To put it another way, Mr. Rubenstein's Trotsky is not Jewish enough. Like Deuts cher, he seems beguiled by Trotsky's own denials. In one sense, this accession i s understandable. How can the biographer say being a Jew was important to Trotsk y when Trotsky's public pronouncements and actionsand even his private behaviorsee m devoid of any sort of Jewish resonance. To harp on his Jewishness, to endow it with special qualities, would play into the most anti-Semitic notions of Jewish ness. But though Trotsky never tired of saying "I'm no Jew, I'm an international ist," he knew very well that nothing would change ingrained prejudices. And so k nowledge of his Jewishness affected his decisions at the most important moment o f his career. Although Mr. Rubenstein conscientiously describes Trotsky's dealings with Jews a

nd Jewish issues, he is wary of attributing any feelings and motivations about T rotsky's ethnicity to Trotsky himself. He never mentions it in analyzing Trotsky 's downfall, for instance, though this is ascribed to many factors: Trotsky's ea rly opposition to Lenin, which many Bolsheviks could not forgive; Trotsky's inde pendent and outspoken attitudes, which, mixed with contempt for his rivals, made it difficult for him to secure allies; Trotsky's refusal to act as ruthlessly a s his opponent; the strange and seemingly psychosomatic fevers that felled Trots ky at critical moments; and Trotsky's absolute faith in the authority of the par ty that was in the vanguard of history and his countervailing lack of faith in i ndividuals. These are all reason enough for Trotsky's decisive failure, and they have been c arefully canvassed in the many other Trotsky biographies. And yet a biographer c harged with looking at a single issue and how it played out in Trotsky's life mi ght just want to exercise a little boldness, not refuting the multiple reasons f or Trotsky's failure to seize power but suffusing them with the underlying premi se that, in the eyes of so many others, once a Jew, always a Jewas Trotsky himsel f knew full well. Only once does Mr. Rubenstein seem to recognize Trotsky's lifelong plight. The b iographer recounts his subject's response to the case of Mendel Beilis, a brickfactory worker accused of murdering a 12-year-old boy in Kiev in 1912, supposedl y to use the blood to prepare matzoh for the Passover holidaythe old blood libel. The trumped-up charges and trial gave rise to world-wide protests and were trea ted by Trotsky as a czarist effort to stir up anti-Semitism (always a useful out let for discontent). Trotsky wrote extensively about the trial (unmentioned in the Deutscher or Servi ce biographies), not merely denouncing it but expressing his disgust even after the jury acquitted Beilis. The cautious Mr. Rubenstein notes that Trotsky's comm itment to social justice had "several sources," none of which Trotsky attributed to his Jewish upbringing. But then, summing up Trotsky's passionate coverage of both the Beilis case and earlier the oppressed Jewish community in Romania, he adds this, the most important passage in his whole book: Perhaps he did not think of himself as a Jew in the same way that they were Jews ; he was a Marxist, a convinced internationalist, a man who resisted any narrow parochial appeal in the name of a universal, political faith. But he had still b een born and raised as a Jew. Perhaps the starkness of their lives touched somet hing so deep inside his emotional life that he needed to vomit it out, to disgor ge it before it compelled him to see himself in their faces. At moments like the se, Leon Trotsky was a Jew in spite of himself. And I would add: not only at those moments. Just at the moment when Trotsky comm anded the world stage and still had time to stop Stalin, he may very well have w ondered about doing permanent injury to the revolution he had done so much to br ing about by now vouchsafing it to a Jew. As an introduction to Trotsky, Mr. Rub enstein's biography is succinct and reliable. As the last word on Trotsky as Jew , it seems surprisingly reluctant to pick up on the strains in history and in Tr otsky's own character that made it impossible for a Jew to command Lenin's legac y.

Você também pode gostar

- UntitledDocumento3 páginasUntitledCarl RollysonAinda não há avaliações

- TolstoyDocumento1 páginaTolstoyCarl RollysonAinda não há avaliações

- UntitledDocumento2 páginasUntitledCarl RollysonAinda não há avaliações

- UntitledDocumento3 páginasUntitledCarl RollysonAinda não há avaliações

- Tillie OlsenDocumento2 páginasTillie OlsenCarl RollysonAinda não há avaliações

- William Jennings BryanDocumento2 páginasWilliam Jennings BryanCarl RollysonAinda não há avaliações

- Margaret SangerDocumento1 páginaMargaret SangerCarl RollysonAinda não há avaliações

- Richard FeynmanDocumento2 páginasRichard FeynmanCarl RollysonAinda não há avaliações

- Margaret FullerDocumento1 páginaMargaret FullerCarl RollysonAinda não há avaliações

- William F. Buckley Jr.Documento1 páginaWilliam F. Buckley Jr.Carl RollysonAinda não há avaliações

- Gypsy Rose LeeDocumento3 páginasGypsy Rose LeeCarl RollysonAinda não há avaliações

- A Slave in The White HouseDocumento2 páginasA Slave in The White HouseCarl RollysonAinda não há avaliações

- James JoyceDocumento1 páginaJames JoyceCarl RollysonAinda não há avaliações

- Joseph SmithDocumento2 páginasJoseph SmithCarl RollysonAinda não há avaliações

- George IIIDocumento2 páginasGeorge IIICarl RollysonAinda não há avaliações

- Beatrix PotterDocumento2 páginasBeatrix PotterCarl RollysonAinda não há avaliações

- Jerome RobbinsDocumento2 páginasJerome RobbinsCarl RollysonAinda não há avaliações

- Patricia HighsmithDocumento1 páginaPatricia HighsmithCarl RollysonAinda não há avaliações

- George SandDocumento2 páginasGeorge SandCarl RollysonAinda não há avaliações

- ToussaintDocumento2 páginasToussaintCarl RollysonAinda não há avaliações

- Leni RiefenstahlDocumento2 páginasLeni RiefenstahlCarl RollysonAinda não há avaliações

- Adolf HitlerDocumento2 páginasAdolf HitlerCarl RollysonAinda não há avaliações

- John LockeDocumento2 páginasJohn LockeCarl RollysonAinda não há avaliações

- Emerson & ErosDocumento2 páginasEmerson & ErosCarl RollysonAinda não há avaliações

- George KennanDocumento2 páginasGeorge KennanCarl RollysonAinda não há avaliações

- Belva LockwoodDocumento2 páginasBelva LockwoodCarl RollysonAinda não há avaliações

- Ernest JonesDocumento2 páginasErnest JonesCarl RollysonAinda não há avaliações

- Ho Chi MinhDocumento2 páginasHo Chi MinhCarl RollysonAinda não há avaliações

- Ho Chi MinhDocumento2 páginasHo Chi MinhCarl RollysonAinda não há avaliações

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeNo EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (5794)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingNo EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (400)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceNo EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (895)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)No EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Nota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (98)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerNo EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (271)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryNo EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (231)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItNo EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (838)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureNo EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (474)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaNo EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (266)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaNo EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (45)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnNo EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (234)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyNo EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (2259)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreNo EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (1090)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersNo EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (344)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)No EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Nota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (121)

- Ca-G.r. SP No. 14994Documento2 páginasCa-G.r. SP No. 14994Net WeightAinda não há avaliações

- Epassport Application Form PDFDocumento1 páginaEpassport Application Form PDFLinelyn Vallo PangilinanAinda não há avaliações

- Chapter 1 - Nature Scope & SignificanceDocumento8 páginasChapter 1 - Nature Scope & SignificancePankaj Sharma100% (1)

- Republic Acts Relevant For LETDocumento2 páginasRepublic Acts Relevant For LETAngelle BahinAinda não há avaliações

- 446-Article Text-1176-1-10-20190521Documento7 páginas446-Article Text-1176-1-10-20190521banu istototoAinda não há avaliações

- TAITZ V ASTRUE (USDC HI) - 15 - ORDER DENYING PLAINTIFF'S EMERGENCY EX PARTE MOTION FOR EMERGENCY ORDER TO SHOW CAUSE AND - Gov - Uscourts.hid.98529.15.0Documento2 páginasTAITZ V ASTRUE (USDC HI) - 15 - ORDER DENYING PLAINTIFF'S EMERGENCY EX PARTE MOTION FOR EMERGENCY ORDER TO SHOW CAUSE AND - Gov - Uscourts.hid.98529.15.0Jack RyanAinda não há avaliações

- Cyber Bullying and Its Effects On The Youth 2Documento4 páginasCyber Bullying and Its Effects On The Youth 2Cam LuceroAinda não há avaliações

- Teknik Bahasa Humor Komedian Sadana Agung Dan KeteDocumento11 páginasTeknik Bahasa Humor Komedian Sadana Agung Dan KeteIlyas Al hafizAinda não há avaliações

- Emergency National Security Supplemental Appropriations Act, 2024Documento370 páginasEmergency National Security Supplemental Appropriations Act, 2024Daily Caller News FoundationAinda não há avaliações

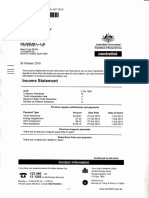

- Income Statement: Llillliltll) Ilililtil)Documento1 páginaIncome Statement: Llillliltll) Ilililtil)Indy EfuAinda não há avaliações

- Autobiography of A 2nd Generation Filipino-AmericanDocumento4 páginasAutobiography of A 2nd Generation Filipino-AmericanAio Min100% (1)

- Resolution No. 9b - S. 2022Documento4 páginasResolution No. 9b - S. 2022John Carlo NuegaAinda não há avaliações

- Final Requirement in Constitutional Law 1 Atty. Malig OnDocumento504 páginasFinal Requirement in Constitutional Law 1 Atty. Malig OnDeeej cartalAinda não há avaliações

- Incorrect Memorandum Following George Washington University Censure VoteDocumento9 páginasIncorrect Memorandum Following George Washington University Censure VoteThe College FixAinda não há avaliações

- History Research PaperDocumento7 páginasHistory Research Paperapi-241248438100% (1)

- MUNRO The Munro Review of Child Protection Final Report A Child-Centred SystemDocumento178 páginasMUNRO The Munro Review of Child Protection Final Report A Child-Centred SystemFrancisco EstradaAinda não há avaliações

- Basic Concepts Tools Gender AnalysisDocumento16 páginasBasic Concepts Tools Gender AnalysisMaria Fiona Duran MerquitaAinda não há avaliações

- What Is Defamation of CharacterDocumento10 páginasWhat Is Defamation of CharacterAkpoghene Lopez SamuelAinda não há avaliações

- Anandi Gopal JoshiDocumento21 páginasAnandi Gopal JoshiTheProject HouseAinda não há avaliações

- Pawb Technical Bulletin NO. 2013-05: (Caves and Cave Resources Conservation, Management and Protection)Documento6 páginasPawb Technical Bulletin NO. 2013-05: (Caves and Cave Resources Conservation, Management and Protection)Billy RavenAinda não há avaliações

- Bock-Ch15 Problems Probability RulesDocumento10 páginasBock-Ch15 Problems Probability RulesTaylorAinda não há avaliações

- Ethos Pathos Fallacy and LogosDocumento6 páginasEthos Pathos Fallacy and Logosapi-272738929100% (1)

- Owens Charge2 PDFDocumento2 páginasOwens Charge2 PDFmjguarigliaAinda não há avaliações

- Development EconomicsDocumento2 páginasDevelopment EconomicsOrn PhatthayaphanAinda não há avaliações

- The GuardianDocumento10 páginasThe GuardianABDUL SHAFIAinda não há avaliações

- Ronald Stevenson Composer-Pianist - An Exegetical Critique From A Pianistic PerspectiveDocumento321 páginasRonald Stevenson Composer-Pianist - An Exegetical Critique From A Pianistic PerspectiveMark GasserAinda não há avaliações

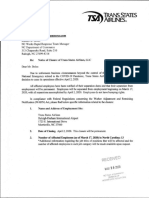

- WARN Trans States AirlinesDocumento2 páginasWARN Trans States AirlinesDavid PurtellAinda não há avaliações

- Marxist Media TheoryDocumento11 páginasMarxist Media TheorymatteocarcassiAinda não há avaliações

- CAANRCDocumento8 páginasCAANRCAaryaman Rathi (Yr. 21-23)Ainda não há avaliações

- PLATODocumento33 páginasPLATOAsim NowrizAinda não há avaliações