Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

Optimistic Futurism

Enviado por

Seymourpowell0 notas0% acharam este documento útil (0 voto)

120 visualizações2 páginasOptimistic futurism began in the early 1950s, but then suddenly it stopped. The '3 day week' in 1974 showed us that we couldn't be considered world-class. Then came several global depressions, shrinking ozone layers, aeroplanes into buildings, global warming.

Descrição original:

Direitos autorais

© Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Formatos disponíveis

PDF, TXT ou leia online no Scribd

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoOptimistic futurism began in the early 1950s, but then suddenly it stopped. The '3 day week' in 1974 showed us that we couldn't be considered world-class. Then came several global depressions, shrinking ozone layers, aeroplanes into buildings, global warming.

Direitos autorais:

Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Formatos disponíveis

Baixe no formato PDF, TXT ou leia online no Scribd

0 notas0% acharam este documento útil (0 voto)

120 visualizações2 páginasOptimistic Futurism

Enviado por

SeymourpowellOptimistic futurism began in the early 1950s, but then suddenly it stopped. The '3 day week' in 1974 showed us that we couldn't be considered world-class. Then came several global depressions, shrinking ozone layers, aeroplanes into buildings, global warming.

Direitos autorais:

Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Formatos disponíveis

Baixe no formato PDF, TXT ou leia online no Scribd

Você está na página 1de 2

Optimistic Futurism

By Richard Seymour

So what the hell happened to the future?

Everything was going just fine in the early1950s, though much of Europe, Japan and the Soviet Union was still flattened under a shroud of ash and broken bricks. Even as the icy grip of the Cold War tightened, those of us that were growing up then, found time to look with thrall and optimism into the future. Men went to the moon and back, Teflon and liquid crystals and lasers and Velcro changed our lives (as had nylon and cellulose before them) and although life wasnt unremitting fun, we could all sense a faint, underpinning mantra: gradually, things were getting better. And then suddenly it stopped. Ive been trying to isolate the moment when it stopped for ages. Some say it was Jack Kennedys assassination. Others claim it wasnt a single moment at all, but a gradual decent into collective depression after the Summer of Love didnt make good on its THC-fuelled dreams. But as far as the UK is concerned, Im absolutely sure I can trace it back to a specific moment: January 1st 1974. The 3 day week as it came to be known, a virtual halving of industrial output, brought on by an energy crisis which arose from industrial action over coal-mining in the UK, showed us Brits that we could no longer be considered world-class at all. Wed finally lost the ability to build big, exciting aeroplanes, Blue Streak, our own, much-vaunted, independant nuclear delivery missile was a dead duck, our railways were screwed and we couldnt run a bath. We suddenly realised we were crap. A couple of years before that, people had run screaming from the initial screenings of A Clockwork Orange claiming that such a barbaric vision of a future dystopia couldnt possibly happen. Now the news slowly began to reveal that Little Alexs ultraviolence was a hideous creeping reality. Then came several global depressions, the end of the Space Age, shrinking ozone layers, aeroplanes into buildings, Global Warming and, bingo, here we are. Comprehensively screwed and wondering what were doing here. If you look around the now, poking around in popular culture, youll usually find a doomy view of the future promulgated - from Japans manga and anime to your regular, everyday news reviews, nihilistic, post-apocalyptic visions prevail. We just dont seem to be able to shake off this maudlin streak in Europe. The French, though, are an exception. And it comes from an unexpected quarter. France has a highly-developed adult cartoon culture, fuelled for a good thirty years by the brilliant foresight of the likes of Bilal and Moebius (Jean Giraud), both graphic novelists from the crucible of modern social imagery: Metal Hurlant. And it is in this unlikely medium that Frances optimistic futurism is at its most obvious. Certainly, it has its dark moments but hidden within the pages of your average French cartoon youll find a core of ebullient humanism trying to get out. Its something we all need to see. Designers cannot be, by definition, pessimists. It just doesnt go with the job. Were supposed to be defining the future, arent we? Populating it with the kit and the buildings and the dcor that everyone else is going to move in to when they get there. If we cant see the world as a better place to live in, then what chance does anyone else have? Its exciting listening to genuine design optimists, like Apples Jonathan Ive, talk about how things are going to get progressively better. Easier. Faster. Simpler. Yummier. Or Gordon Murray, waxing lyrical about how hes left McLaren to sort out city mobility. Or designer-come-wizard Tom Heatherwick, giggling like a schoolboy because hes turned a bridge in Docklands into a living, breathing piece of mechanical ballet in front of yet another haughty Richard Rodgers glasshouse. Its exciting because I believe them. And its exciting because these people are embracing big, complicated issues which affect all of us, not just running away into a corner to design yet another salt and pepper pot for an Italian luxury goods company. And its exciting because, in this postconvergent world, we really can fix a lot of the stuff that didnt serve us well before. We can make sure that impossible-to-programme crap like VCRs dont happen again. We can connect ourselves to virtually anyone around the planet, for any number of reasons and for a fraction of the price. We can fix shopping for disabled people. We could even convert a bus system into a book-your-seat personal limo service. We can do almost anything we can imagine now, if we put our minds to it. Which puts us squarely in the same position as our forebears were in the early 16th century, with a new age of technology and capability stretching out in front of us, as far as the eye can see, if we only choose to. So now its no longer down to what we can do its about what we should do. And that takes more than just imagination, it takes wisdom. For instance, distributing power generation to the point of use, such as in the infrastructures imagined in the Hydrogen economy, could utterly revolutionise the way we live. It doesnt have to be done all at once. We can do it a bit at a time and still win. Even apparently tiny changes can still make a phenomenal difference. In the US three years ago, five large schools got together to see what impact that tiny folding, aluminium kids scooter had made to the school run. They calculated the fuel saving over a year, where Mom wasnt using the SUV to take junior to

Optimistic Furturism (cont)

school, but walking with him scooting his little steed instead. They made a phenomenal discovery. Over only five schools, the fuel saving was an amazing 830,000 gallons of gasoline, almost enough to drive a compact European car to the Sun! Theres nothing on the planet that cant be made just that bit better (rather than just that bit different). But before you do it, you need to have an idea where you want all this to go eventually, a vision of the future, with a set of stepping stones to let you get from the now into the future in an effective and efficient way. Dan Dare, Pilot of the Future, an exquisitelyillustrated comic strip did this beautifully in the 50s and 60s, portraying a virtually utopian future with recognisable emotional signposts along the way. The planet-hopping shuttle rocket in this picture is surrounded by battered leather suitcases with Mars stickers on them. Thats not because the illustrator/futurist Frank Hampson lacked the vision to imagine the luggage of the future, it was just his little way of saying: Itll be everything you dreamed of, but with all your favourite, familiar stuff still there. And thats what we should be doing: leading the way by visualising and articulating achievable futures that get us out of this hole. Im pretty sure Apple dont call themselves optimistic futurists, but thats exactly what they are. My favourite Steve Jobs one-liner is: Its not the consumers job to know about the future, thats my job. And hes absolutely right. Jurassic corporations need to learn from the mammals. The secret of the next big thing isnt lurking inside the consumers head, waiting to be liberated by some wellpaid focus group. Its inside the heads of the dreamers, the futurists, the Utopians. You and me. And sometimes we get despondent and knocked-back by the beancounters who tell us were wrong and that the consumer is always right. Or by the supply chain who say it cant be done. Or by the MD who cant see further than his own Excel spreadsheet. But the difference is that were the ones with the imagination to see beyond what things are, which is why we applied for art college in the first place, rather than accountancy or law. If I wake up depressed tomorrow and design a really bad poster for hair gel, whos going to give a damn? (other than the client). If I get The shape of things to come up and design a really bad train, though, Im going to visit a trillion devils on thousands of people for years to come. History tells us that before great business can happen, it first has to be a Mission. And a Mission starts with a Dream. As designers, we potentially hold enormous power. And with it comes responsibility. Wield it imaginatively and wisely. And optimistically. Or fuck off and do something less dangerous.

Theres nothing on the planet that cant be made just that bit better (rather than just that bit different).

Você também pode gostar

- Milan in Perspective 2014Documento15 páginasMilan in Perspective 2014SeymourpowellAinda não há avaliações

- A View On MasculinityDocumento11 páginasA View On MasculinitySeymourpowellAinda não há avaliações

- Wearable Technology - Learning, Connecting, Monitoring and PosingDocumento11 páginasWearable Technology - Learning, Connecting, Monitoring and PosingSeymourpowell100% (1)

- Milan in Perspective 2013: Design DualityDocumento13 páginasMilan in Perspective 2013: Design DualitySeymourpowellAinda não há avaliações

- Seymourpowell Newsbook Autumn/Winter 2012Documento31 páginasSeymourpowell Newsbook Autumn/Winter 2012SeymourpowellAinda não há avaliações

- In Conversation With Richard SeymourDocumento3 páginasIn Conversation With Richard SeymourSeymourpowellAinda não há avaliações

- Seymourpowell Design Multiple-Award-Winning Products & Product Identity For KT (Korea Telecom)Documento4 páginasSeymourpowell Design Multiple-Award-Winning Products & Product Identity For KT (Korea Telecom)SeymourpowellAinda não há avaliações

- Many Routes, One Destination - The Sustainable Design CompassDocumento24 páginasMany Routes, One Destination - The Sustainable Design CompassSeymourpowellAinda não há avaliações

- Violence of The NewDocumento3 páginasViolence of The NewSeymourpowellAinda não há avaliações

- Key Trends From CES 2013Documento7 páginasKey Trends From CES 2013SeymourpowellAinda não há avaliações

- Sustainability in BriefDocumento3 páginasSustainability in BriefSeymourpowellAinda não há avaliações

- How Good Designers ThinkDocumento4 páginasHow Good Designers ThinkSeymourpowellAinda não há avaliações

- An Innovative Path To A Greener FutureDocumento3 páginasAn Innovative Path To A Greener FutureSeymourpowellAinda não há avaliações

- Is The Customer Always RightDocumento5 páginasIs The Customer Always RightSeymourpowellAinda não há avaliações

- Marketing Week 181012Documento1 páginaMarketing Week 181012SeymourpowellAinda não há avaliações

- Authenticity in Fairy TalesDocumento3 páginasAuthenticity in Fairy TalesSeymourpowellAinda não há avaliações

- How Will The Evolution of Video Games Influence The Products We Surround Ourselves With in The Future?Documento3 páginasHow Will The Evolution of Video Games Influence The Products We Surround Ourselves With in The Future?SeymourpowellAinda não há avaliações

- Milan in Perspective 2012Documento10 páginasMilan in Perspective 2012SeymourpowellAinda não há avaliações

- Innovation in AviationDocumento4 páginasInnovation in AviationSeymourpowellAinda não há avaliações

- Loving The AliensDocumento2 páginasLoving The AliensSeymourpowellAinda não há avaliações

- Becoming Dai-SenseiDocumento5 páginasBecoming Dai-SenseiSeymourpowellAinda não há avaliações

- An Inconvenient Truth About Transformational InnovationDocumento4 páginasAn Inconvenient Truth About Transformational InnovationSeymourpowellAinda não há avaliações

- Fat Snake and The DumbbellDocumento7 páginasFat Snake and The DumbbellSeymourpowellAinda não há avaliações

- Future of The FutureDocumento8 páginasFuture of The FutureSeymourpowellAinda não há avaliações

- ProPlanCat Press Release 12 March 2012Documento4 páginasProPlanCat Press Release 12 March 2012SeymourpowellAinda não há avaliações

- Chris Sherwin Joins Seymourpowell 2012Documento3 páginasChris Sherwin Joins Seymourpowell 2012SeymourpowellAinda não há avaliações

- Ethnography's Importance To BusinessDocumento5 páginasEthnography's Importance To BusinessSeymourpowellAinda não há avaliações

- Bringing Ideas To LifeDocumento4 páginasBringing Ideas To LifeSeymourpowellAinda não há avaliações

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItNo EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (838)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureNo EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (474)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeNo EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (5783)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceNo EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (890)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)No EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Nota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (98)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingNo EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (399)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryNo EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnNo EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (234)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaNo EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (265)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersNo EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (344)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerNo EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (271)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyNo EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (2219)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaNo EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreNo EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)No EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Nota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (119)

- ABC Australia Seeks Wide Variety of Genres for KidsDocumento11 páginasABC Australia Seeks Wide Variety of Genres for Kidsdudaxavier100% (2)

- Applying Graph Theory to Map ColoringDocumento25 páginasApplying Graph Theory to Map ColoringAnonymous BOreSFAinda não há avaliações

- Graphics Educational TechnologyDocumento4 páginasGraphics Educational TechnologyJude Angelo Barrozo GeminoAinda não há avaliações

- Sylvannas LoreDocumento19 páginasSylvannas LorebogdyloveAinda não há avaliações

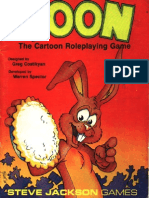

- Toon - The Cartoon RPGDocumento66 páginasToon - The Cartoon RPGBluesinha100% (7)

- 3RD QTR-G12Documento13 páginas3RD QTR-G12ALLEN JOSEPH ONGAinda não há avaliações

- First Toondoo Student GuideDocumento11 páginasFirst Toondoo Student Guideapi-288902605Ainda não há avaliações

- Philippine arts worksheetDocumento3 páginasPhilippine arts worksheetKyla CandontolAinda não há avaliações

- Comics BlondieDocumento3 páginasComics Blondiemimi meAinda não há avaliações

- CorelPainCorel Painter - 08 - Magazine, Art, Digital Painting, Drawing, Draw, 2dDocumento92 páginasCorelPainCorel Painter - 08 - Magazine, Art, Digital Painting, Drawing, Draw, 2dFlie67% (3)

- Japanese Movies PDFDocumento1 páginaJapanese Movies PDFcccAinda não há avaliações

- Spaced Analysis Spaced Season 1 Episode 4 (Battles)Documento1 páginaSpaced Analysis Spaced Season 1 Episode 4 (Battles)Anonymous DcN05DAinda não há avaliações

- Assignment Two CartoonsDocumento3 páginasAssignment Two CartoonsAbraham Kang100% (1)

- Presentation - CartooningDocumento44 páginasPresentation - CartooningEloisa Micah GuabesAinda não há avaliações

- Grade 9Documento45 páginasGrade 9Fransil SaysonAinda não há avaliações

- Seahorse Life CyclesDocumento16 páginasSeahorse Life Cyclesta_1091Ainda não há avaliações

- The Philippine National Artists For Visual ArtDocumento2 páginasThe Philippine National Artists For Visual ArtMelca Miikay MalatagAinda não há avaliações

- Film National Media Television Radio Museum Web PhotographyDocumento3 páginasFilm National Media Television Radio Museum Web PhotographyChristian Andrés GrammáticoAinda não há avaliações

- Mangajin63 - Joy of A Japanese BathDocumento66 páginasMangajin63 - Joy of A Japanese Bathdustinbr100% (1)

- Name: Sabira Rafique Subject: Biology Topic: Av Aids Department: Education Submitted To: Ma'am Aliya Ayub Date of Submission: 21Documento10 páginasName: Sabira Rafique Subject: Biology Topic: Av Aids Department: Education Submitted To: Ma'am Aliya Ayub Date of Submission: 21Irfan EssazaiAinda não há avaliações

- Alfred McCoy's Political Cartoons of the American EraDocumento13 páginasAlfred McCoy's Political Cartoons of the American Eramaricrisandem40% (5)

- The Black PantherDocumento6 páginasThe Black Pantherapi-235326611Ainda não há avaliações

- Online Greenlight ReviewDocumento10 páginasOnline Greenlight ReviewsbpayneAinda não há avaliações

- IB History IADocumento13 páginasIB History IAAngelina Fokina100% (1)

- Aiesec University: 1. Two Truths, One LieDocumento3 páginasAiesec University: 1. Two Truths, One LieGeorgianaAinda não há avaliações

- Joke Best Comedy2Documento118 páginasJoke Best Comedy2tyldermineAinda não há avaliações

- Kitaro's Yokai Battles Shigeru MizukiDocumento37 páginasKitaro's Yokai Battles Shigeru MizukiRenato AraujoAinda não há avaliações

- Relative clauses and Miyazaki's animated filmsDocumento3 páginasRelative clauses and Miyazaki's animated filmsandres palaciosAinda não há avaliações

- Corel Painter - 15 - Imagine Publishing LTD PDFDocumento78 páginasCorel Painter - 15 - Imagine Publishing LTD PDFHUknows1Ainda não há avaliações

- Hugh Harman: CareerDocumento3 páginasHugh Harman: CareerT NgAinda não há avaliações