Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

Pathophysiology of Hypothermia

Enviado por

Gracel QuiaotDescrição original:

Direitos autorais

Formatos disponíveis

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Pathophysiology of Hypothermia

Enviado por

Gracel QuiaotDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

NCM 103 FLUIDS AND ELECTROLYTES

HYPOTHERMIA

Pathophysiology and Management

Submitted by: ASIS, ANGELICA P. BSN 219

Conduction and Convection Respiration and Evaporation Circulating Air

Heat Loss

Dry Conditions and Radiation Direct transfer of heat to another object Drowning/ Immersion of water

Stimulation of Hypothalamus Thermoregulation

Increase Heat Production

Shivering

Thyroxine and Epinephrine

O2 consumption and caloric demands

Vasoconstriction

Overwhelmed mechanism for heat preservation Drop of core temperature HYPOTHERMIA

Depolarization of cardiac pacemakers

CNS Depression

Bradycardia

Atrial and Ventricular arrhythmia

Abnormal Electrical Activity Brain Death

MANAGEMENT Gentle rewarming of the patient.

To perform this, three main techniques are available. These are passive rewarming, active external rewarming and active internal rewarming. In passive rewarming, wet clothing should be removed and the patient well insulated at room temperature, including the head, to prevent further heat loss while the bodys natural thermogenesis is relied upon to restore body temperature. Proponents of this method argue that it is the most physiological and it is thought that it reduces the incidence of rewarming shock. However, failure to rewarm or the presence of dysrhythmias are not good prognostic signs and indicate that a more aggressive approach is required.

Active external rewarming relies on a heat source applied to the body and therefore depends on the conduction of heat through the skin. Methods currently used are warming blankets, heating pads or immersion of the patient in a bath maintained at a temperature around 40C. Caution must be taken with heating pads as skin injury can occur while monitoring is made virtually impossible by submersion in water. Hence the later technique should only be used for those who are conscious, shivering, uninjured and able to get in and out of the bath unaided. Nevertheless, the advantage of active external rewarming is that rewarming occurs more rapidly than with passive rewarming, particularly if the patient has impaired thermoregulatory function.

In active internal rewarming heated fluid or humidified gas is delivered internally. Humidified and warmed oxygen can be given, thereby warming and effectively insulating the patients airways. Heated peritoneal lavage warms the heart through the diaphragm and blood returning via the inferior vena cava, stabilising cardiac conduction. It is a relatively safe and simple technique, although it is contraindicated in intra-abdominal trauma and cases of severe intra-abdominal sepsis and disseminated intravascular coagulation have been reported. Fluids, including blood, can be warmed and given intravenously, although the risk of fluid overload and cardiac failure must be considered. Finally, heated cardiopulmonary bypass provides extracorporeal rewarming and circulatory support, with this technique providing the most rapid and physiological method of internal rewarming as the core is rewarmed first. However, an experienced team is required and it has been argued that this technique is unnecessarily invasive. In practice, extracorporeal warming is usually adopted only if other methods have failed.

While rewarming occurs, a number of supportive measures may require implementation and patients should have their vital signs monitored to detect any possible complications. If the gag reflex or ventilation is inadequate, endotracheal intubation may be required. However, in an attempt to avoid dysrhythmias, the hypothermic patient should be handled gently and the ECG continuously monitored. Consequently, chest compressions should only be commenced by rescuers prior to hospital admission if there is no carotid pulse palpable for at least one minute and it will be possible to continue the compressions until hospital or other location.

If hypothermia has been prolonged, patients may be hypovolaemic and therefore warmed fluids should be given and the bladder catheterised. Blood glucose may initial be high but falls as rewarming progresses, so 50% glucose solution may be necessary. In this situation, glucagon is not usually effective as the majority of patients will have depleted their glycogen stores. As many hypothermic patients are alcoholics, vitamin B, particularly thiamine, should be given to avoid the complication of acute Wernicke's encephalopathy. Acidosis is not normally corrected with bicarbonate as the patients metabolic picture changes rapidly throughout the rewarming process and over vigorous correction results in alkalaemia, which may predispose to arrhythmias. Finally, if gastric dilatation and poor gastric mobility exist, the insertion of a nasogastric tube is an option.

The use of drugs should be avoided as they are ineffective at lower temperatures and may cause unwanted side effects as the patient is rewarmed. Exceptions to this are oxygen, dextrose, naloxone and thiamine.

Bloods should be taken for full blood count, urea and electrolytes, amylase, clotting and, in severe hypothermia, blood gases. Toxicology screens may be appropriate. A chest x-ray is also essential to exclude a subsequent pneumonia or adult respiratory distress syndrome.2

Você também pode gostar

- Acute Lymphoblastic LeukemiaDocumento34 páginasAcute Lymphoblastic LeukemiamtyboyAinda não há avaliações

- Perioperative HypothermiaDocumento4 páginasPerioperative Hypothermiasri utari masyitahAinda não há avaliações

- CnsDocumento15 páginasCnsArun GeorgeAinda não há avaliações

- Oxygen Delivery DevicesDocumento7 páginasOxygen Delivery DevicesPleural Effusion0% (1)

- Acute Disease Case Study: Metabolism - HypothermiaDocumento8 páginasAcute Disease Case Study: Metabolism - HypothermiaRegina PerkinsAinda não há avaliações

- Risk For InfectionDocumento7 páginasRisk For InfectionAnn Michelle TarrobagoAinda não há avaliações

- Umbilical Cord ProlapseDocumento6 páginasUmbilical Cord ProlapseCeth BeltranAinda não há avaliações

- Introduction - MIDocumento10 páginasIntroduction - MIkhimiiiAinda não há avaliações

- Family Care PlanDocumento3 páginasFamily Care PlanAngie MandeoyaAinda não há avaliações

- Frostbite and HypothermiaDocumento43 páginasFrostbite and HypothermiaBlade DarkmanAinda não há avaliações

- Tetralogy of Fallot: Arianna Jasminemabunga Bsn-2BDocumento30 páginasTetralogy of Fallot: Arianna Jasminemabunga Bsn-2BArianna Jasmine MabungaAinda não há avaliações

- Toxic Megacolon...Documento10 páginasToxic Megacolon...Vikas MataiAinda não há avaliações

- Pleural EffusionDocumento12 páginasPleural EffusionWan HafizAinda não há avaliações

- ThrombocytopeniaDocumento2 páginasThrombocytopeniaNeoMedica100% (1)

- Uremic EncephalophatyDocumento48 páginasUremic EncephalophatySindi LadayaAinda não há avaliações

- Amniotic Fluid Embolism ArticleDocumento3 páginasAmniotic Fluid Embolism ArticleShailesh JainAinda não há avaliações

- About Critical Care NursingDocumento7 páginasAbout Critical Care NursingaivynAinda não há avaliações

- Acute Renal FailureDocumento19 páginasAcute Renal Failurebala.mAinda não há avaliações

- Management of Diabetic Ketoacidosis: MW SavageDocumento3 páginasManagement of Diabetic Ketoacidosis: MW SavagedramaysinghAinda não há avaliações

- Rosalina Q. de Sagun, M.D. Maria Antonia Aurora Moral - Valencia, M.DDocumento52 páginasRosalina Q. de Sagun, M.D. Maria Antonia Aurora Moral - Valencia, M.DDaphne Jo ValmonteAinda não há avaliações

- GROUP 3 - CASE STUDY - TraumaDocumento5 páginasGROUP 3 - CASE STUDY - TraumaDinarkram Rabreca EculAinda não há avaliações

- Pathophysiology of Ischemic Stroke - UpToDateDocumento11 páginasPathophysiology of Ischemic Stroke - UpToDateKarla AldamaAinda não há avaliações

- Epilepsy in Pregnancy JatuDocumento57 páginasEpilepsy in Pregnancy Jatuninjahattori1Ainda não há avaliações

- Massive BleedingpptDocumento24 páginasMassive BleedingpptFidel Gimotea Yongque IIIAinda não há avaliações

- Case Scenario CVDocumento14 páginasCase Scenario CVjohnhenryvAinda não há avaliações

- Amniotic Fluid EmbolismDocumento13 páginasAmniotic Fluid Embolismelfa riniAinda não há avaliações

- Head InjuryDocumento2 páginasHead InjuryPheiyi WongAinda não há avaliações

- Revised BPHDocumento2 páginasRevised BPHCyril Jane Caanyagan AcutAinda não há avaliações

- Pleurisy (Pleuritis)Documento17 páginasPleurisy (Pleuritis)kamilahfernandezAinda não há avaliações

- City of Manila (Formerly City College of Manila) Mehan Gardens, ManilaDocumento8 páginasCity of Manila (Formerly City College of Manila) Mehan Gardens, Manilaicecreamcone_201Ainda não há avaliações

- THROMBOPHLEBITISDocumento50 páginasTHROMBOPHLEBITISmers puno100% (3)

- Intracranial Hemorrhage - Hatfield 11 2018Documento51 páginasIntracranial Hemorrhage - Hatfield 11 2018Sebastian Mora LópezAinda não há avaliações

- Drugs Affecting The Respiratory SystemDocumento4 páginasDrugs Affecting The Respiratory SystemJerica Jaz F. Vergara100% (1)

- Aldactone SpironlactoneDocumento1 páginaAldactone SpironlactoneCassie100% (1)

- Case Report ThymomaDocumento18 páginasCase Report ThymomaFatur ReyhanAinda não há avaliações

- Chapter 067 Sirs ModsDocumento25 páginasChapter 067 Sirs Modsapi-232466940Ainda não há avaliações

- NCP For Breast CancerDocumento2 páginasNCP For Breast Cancergeng gengAinda não há avaliações

- Cardiogenic Shock and HemodynamicsDocumento18 páginasCardiogenic Shock and HemodynamicsfikriAinda não há avaliações

- Case Studies - Tetralogy of FallotDocumento16 páginasCase Studies - Tetralogy of FallotKunwar Sidharth SaurabhAinda não há avaliações

- Methods in Assessing Fetal Well-BeingDocumento27 páginasMethods in Assessing Fetal Well-BeingPasay Trisha Faye Y.Ainda não há avaliações

- Agn PDFDocumento6 páginasAgn PDFMohamed ZiadaAinda não há avaliações

- Generic Name:: Drug Name Indicatio N Mechanism of Action Side Effects Nursing ResponsibilitiesDocumento1 páginaGeneric Name:: Drug Name Indicatio N Mechanism of Action Side Effects Nursing Responsibilitiesgrace pitogoAinda não há avaliações

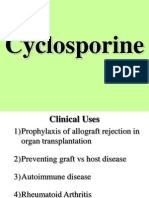

- CyclosporineDocumento24 páginasCyclosporinesanchit_J14Ainda não há avaliações

- Hypovolemic Shock TEXTDocumento5 páginasHypovolemic Shock TEXTrhen1991Ainda não há avaliações

- Drug StudyDocumento2 páginasDrug StudyJi Vista MamigoAinda não há avaliações

- Jade R. Dinolan BSN-4: Diagnosi SDocumento5 páginasJade R. Dinolan BSN-4: Diagnosi SJhade Relleta100% (1)

- Cold Injury and HypothermiaDocumento31 páginasCold Injury and HypothermiatparamesparanAinda não há avaliações

- Hydrocephalus in Adult PresentDocumento25 páginasHydrocephalus in Adult PresentmarthintoriAinda não há avaliações

- 1 - Presentation - Management of Preclamplsia, Mild and ModerateDocumento22 páginas1 - Presentation - Management of Preclamplsia, Mild and ModeratesharonAinda não há avaliações

- Pathophysiology of MalariaDocumento20 páginasPathophysiology of Malariamelia100% (1)

- Abruptio PlacentaeDocumento4 páginasAbruptio PlacentaeMelissa Aina Mohd YusofAinda não há avaliações

- Submersion Injuries: Richard Dionne MD CCFP-EM Avik Nath MD CCFP emDocumento29 páginasSubmersion Injuries: Richard Dionne MD CCFP-EM Avik Nath MD CCFP emRuDy RaviAinda não há avaliações

- Pathophysiology: Risk FactorsDocumento4 páginasPathophysiology: Risk FactorsEdson John DemayoAinda não há avaliações

- CRANIOTOMYDocumento31 páginasCRANIOTOMYDrVarun KaliaAinda não há avaliações

- Valvularheart Diseases: PathophysiologyDocumento9 páginasValvularheart Diseases: PathophysiologyVoid LessAinda não há avaliações

- Drug Study (AGN)Documento10 páginasDrug Study (AGN)kristineAinda não há avaliações

- ABC Near DrowningDocumento3 páginasABC Near DrowningAhmad FachrurroziAinda não há avaliações

- Critical Care in The Emergency Department: Shock and Circulatory SupportDocumento10 páginasCritical Care in The Emergency Department: Shock and Circulatory SupportKhaled AbdoAinda não há avaliações

- Bahan Dasar Uji Gula GulaDocumento3 páginasBahan Dasar Uji Gula GulavannyAinda não há avaliações

- Promoting Adequate Gas ExchangeDocumento5 páginasPromoting Adequate Gas Exchangeali sarjunipadangAinda não há avaliações

- Lymphatic SystemDocumento22 páginasLymphatic SystemJohn MenesesAinda não há avaliações

- Physiology of The Liver: Corresponding AuthorDocumento12 páginasPhysiology of The Liver: Corresponding AuthorMansour HazaAinda não há avaliações

- Partial E-Tool HA - Abdomen PDFDocumento2 páginasPartial E-Tool HA - Abdomen PDFNicole BertulfoAinda não há avaliações

- Safety Tracker in Excel For HSE ProfessionalsDocumento22 páginasSafety Tracker in Excel For HSE Professionalsngomsia parfaitAinda não há avaliações

- Para Sample QuestionsDocumento5 páginasPara Sample QuestionsMaria Christina LagartejaAinda não há avaliações

- 24, Standards For Blood Banks and Blood Transfusion ServicesDocumento111 páginas24, Standards For Blood Banks and Blood Transfusion ServicesShiv Shankar Tiwari67% (3)

- Decalcifiying Pineal GlandDocumento8 páginasDecalcifiying Pineal Glandsonden_291% (11)

- TangladDocumento10 páginasTangladKwen AnascaAinda não há avaliações

- Natural Remedies For FibroidsDocumento2 páginasNatural Remedies For Fibroidsafm2026Ainda não há avaliações

- Neck Lump HistoryDocumento4 páginasNeck Lump HistoryAlmomnbllah Ahmed100% (1)

- Lungs and Lung Disease QuestionsDocumento16 páginasLungs and Lung Disease QuestionsrkblsistemAinda não há avaliações

- 2.biomekanik Pada Edentulus PenuhDocumento27 páginas2.biomekanik Pada Edentulus PenuhJesica Dwiasta Octaria NainggolanAinda não há avaliações

- Alfred T. Schofield - Nerves in Disorder (1903)Documento224 páginasAlfred T. Schofield - Nerves in Disorder (1903)momir6856Ainda não há avaliações

- Narrative TextDocumento7 páginasNarrative TextNorma AyunitaAinda não há avaliações

- Ace Reasoning New AddaDocumento359 páginasAce Reasoning New Addajuinarka24112002Ainda não há avaliações

- MCQSDocumento3 páginasMCQSShahzad RasoolAinda não há avaliações

- Quiz ReproductiveDocumento78 páginasQuiz ReproductiveMedShare86% (7)

- Hemichordata and Invertebrate ChordatesDocumento31 páginasHemichordata and Invertebrate ChordatesayonAinda não há avaliações

- Oral Histology Quiz - True False (AmCoFam)Documento35 páginasOral Histology Quiz - True False (AmCoFam)AmericanCornerFamily88% (8)

- PSTAdec 2017Documento586 páginasPSTAdec 2017Ryan Bacarro BagayanAinda não há avaliações

- History of NeuroscienceDocumento17 páginasHistory of NeurosciencerazorviperAinda não há avaliações

- Occlusal AnalysisDocumento14 páginasOcclusal AnalysisDavid DongAinda não há avaliações

- Parasitology Case Presentation: Group 3Documento42 páginasParasitology Case Presentation: Group 3Christine Joy LegaspiAinda não há avaliações

- Hospital Patient Chart Free PDF Download PDFDocumento1 páginaHospital Patient Chart Free PDF Download PDFnila nurilAinda não há avaliações

- Anatomy and Physiology of Oral CavityDocumento15 páginasAnatomy and Physiology of Oral Cavity28 manan patelAinda não há avaliações

- Abp 10 Years PDFDocumento44 páginasAbp 10 Years PDFUtsabAinda não há avaliações

- MP - Hardgainer GuideDocumento14 páginasMP - Hardgainer GuideAnthony Dinicolantonio100% (2)

- Nervous SystemDocumento2 páginasNervous SystemShanel Aubrey AglibutAinda não há avaliações

- Pyeronie Disease and HomoeopathyDocumento16 páginasPyeronie Disease and HomoeopathyDr. Rajneesh Kumar Sharma MD HomAinda não há avaliações

- Studi Kasus: Pemalsuan Daging Sapi Dengan Daging Babi Hutan Di Kota Bogor Lailatun Nida, Herwin Pisestyani, Chaerul BasriDocumento10 páginasStudi Kasus: Pemalsuan Daging Sapi Dengan Daging Babi Hutan Di Kota Bogor Lailatun Nida, Herwin Pisestyani, Chaerul Basriclarentina aristawatiAinda não há avaliações

- Love Life: How to Raise Your Standards, Find Your Person, and Live Happily (No Matter What)No EverandLove Life: How to Raise Your Standards, Find Your Person, and Live Happily (No Matter What)Nota: 3 de 5 estrelas3/5 (1)

- LIT: Life Ignition Tools: Use Nature's Playbook to Energize Your Brain, Spark Ideas, and Ignite ActionNo EverandLIT: Life Ignition Tools: Use Nature's Playbook to Energize Your Brain, Spark Ideas, and Ignite ActionNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (404)

- By the Time You Read This: The Space between Cheslie's Smile and Mental Illness—Her Story in Her Own WordsNo EverandBy the Time You Read This: The Space between Cheslie's Smile and Mental Illness—Her Story in Her Own WordsAinda não há avaliações

- The Age of Magical Overthinking: Notes on Modern IrrationalityNo EverandThe Age of Magical Overthinking: Notes on Modern IrrationalityNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (31)

- Summary: Outlive: The Science and Art of Longevity by Peter Attia MD, With Bill Gifford: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisNo EverandSummary: Outlive: The Science and Art of Longevity by Peter Attia MD, With Bill Gifford: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (42)

- ADHD is Awesome: A Guide to (Mostly) Thriving with ADHDNo EverandADHD is Awesome: A Guide to (Mostly) Thriving with ADHDNota: 5 de 5 estrelas5/5 (3)

- Think This, Not That: 12 Mindshifts to Breakthrough Limiting Beliefs and Become Who You Were Born to BeNo EverandThink This, Not That: 12 Mindshifts to Breakthrough Limiting Beliefs and Become Who You Were Born to BeNota: 2 de 5 estrelas2/5 (1)

- Summary: The Psychology of Money: Timeless Lessons on Wealth, Greed, and Happiness by Morgan Housel: Key Takeaways, Summary & Analysis IncludedNo EverandSummary: The Psychology of Money: Timeless Lessons on Wealth, Greed, and Happiness by Morgan Housel: Key Takeaways, Summary & Analysis IncludedNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (82)

- Cult, A Love Story: Ten Years Inside a Canadian Cult and the Subsequent Long Road of RecoveryNo EverandCult, A Love Story: Ten Years Inside a Canadian Cult and the Subsequent Long Road of RecoveryNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (46)

- The Body Keeps the Score by Bessel Van der Kolk, M.D. - Book Summary: Brain, Mind, and Body in the Healing of TraumaNo EverandThe Body Keeps the Score by Bessel Van der Kolk, M.D. - Book Summary: Brain, Mind, and Body in the Healing of TraumaNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (266)

- The Ritual Effect: From Habit to Ritual, Harness the Surprising Power of Everyday ActionsNo EverandThe Ritual Effect: From Habit to Ritual, Harness the Surprising Power of Everyday ActionsNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (4)

- The Obesity Code: Unlocking the Secrets of Weight LossNo EverandThe Obesity Code: Unlocking the Secrets of Weight LossNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (6)

- Manipulation: The Ultimate Guide To Influence People with Persuasion, Mind Control and NLP With Highly Effective Manipulation TechniquesNo EverandManipulation: The Ultimate Guide To Influence People with Persuasion, Mind Control and NLP With Highly Effective Manipulation TechniquesNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (1412)

- Raising Mentally Strong Kids: How to Combine the Power of Neuroscience with Love and Logic to Grow Confident, Kind, Responsible, and Resilient Children and Young AdultsNo EverandRaising Mentally Strong Kids: How to Combine the Power of Neuroscience with Love and Logic to Grow Confident, Kind, Responsible, and Resilient Children and Young AdultsNota: 5 de 5 estrelas5/5 (1)

- Dark Psychology & Manipulation: Discover How To Analyze People and Master Human Behaviour Using Emotional Influence Techniques, Body Language Secrets, Covert NLP, Speed Reading, and Hypnosis.No EverandDark Psychology & Manipulation: Discover How To Analyze People and Master Human Behaviour Using Emotional Influence Techniques, Body Language Secrets, Covert NLP, Speed Reading, and Hypnosis.Nota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (110)

- Why We Die: The New Science of Aging and the Quest for ImmortalityNo EverandWhy We Die: The New Science of Aging and the Quest for ImmortalityNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (5)

- Raising Good Humans: A Mindful Guide to Breaking the Cycle of Reactive Parenting and Raising Kind, Confident KidsNo EverandRaising Good Humans: A Mindful Guide to Breaking the Cycle of Reactive Parenting and Raising Kind, Confident KidsNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (170)

- Summary: Limitless: Upgrade Your Brain, Learn Anything Faster, and Unlock Your Exceptional Life By Jim Kwik: Key Takeaways, Summary and AnalysisNo EverandSummary: Limitless: Upgrade Your Brain, Learn Anything Faster, and Unlock Your Exceptional Life By Jim Kwik: Key Takeaways, Summary and AnalysisNota: 5 de 5 estrelas5/5 (8)

- When the Body Says No by Gabor Maté: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisNo EverandWhen the Body Says No by Gabor Maté: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (2)

- Mindset by Carol S. Dweck - Book Summary: The New Psychology of SuccessNo EverandMindset by Carol S. Dweck - Book Summary: The New Psychology of SuccessNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (328)

- Troubled: A Memoir of Foster Care, Family, and Social ClassNo EverandTroubled: A Memoir of Foster Care, Family, and Social ClassNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (27)

- Dark Psychology: Learn To Influence Anyone Using Mind Control, Manipulation And Deception With Secret Techniques Of Dark Persuasion, Undetected Mind Control, Mind Games, Hypnotism And BrainwashingNo EverandDark Psychology: Learn To Influence Anyone Using Mind Control, Manipulation And Deception With Secret Techniques Of Dark Persuasion, Undetected Mind Control, Mind Games, Hypnotism And BrainwashingNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (1138)

- The Courage Habit: How to Accept Your Fears, Release the Past, and Live Your Courageous LifeNo EverandThe Courage Habit: How to Accept Your Fears, Release the Past, and Live Your Courageous LifeNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (253)