Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

Roger Fry Art Commerce

Enviado por

ndegen_galleryDescrição original:

Direitos autorais

Formatos disponíveis

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Roger Fry Art Commerce

Enviado por

ndegen_galleryDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Journal of Cultural Economics 22: 4347, 1998. 1998 Kluwer Academic Publishers. Printed in the Netherlands.

43

Classic Article reprint series

Roger Fry: Art and Commerce

Introduction

CRAUFURD D. GOODWIN

Duke University, Department of Economics, Durhan, North Carolina 277080097, U.S.A.

Roger Fry (18661934) was at various times art critic, historian, painter, journalist, aesthetician, museum curator, advisor to government, and entrepreneur in the art world as gallery operator, consultant to collectors and modest speculator (Spalding, 1980 and Woolf [1940], 1976). He is perhaps remembered best as organizer of the two Postimpressionist art exhibitions in London in 1910 and 1912 that introduced Cezanne, Matisse, Van Gogh, Picasso, and other radical painters to the English speaking world, as the proprietor of the Omega Workshops (19131919), and as a core member of the Bloomsbury Group, that informal community of artists and intellectuals that included, among others, Virginia and Leonard Woolf, Lytton Strachey, E. M. Forster, and John Maynard Keynes. Fry was a remarkable polymath, a modern Renaissance man. He was trained as a scientist and received a double rst in natural sciences at Cambridge. But he spent his career in the arts. He had insatiable curiosity, and he could not resist plunging into with gusto, and writing condently about, any subject that caught his fancy in the arts, humanities, applied science, architecture, and the social and behavioral sciences from the poems of Mallerm to the psychoanalysis of Freud. He maintained ties with Cambridge over his lifetime but he was never a conventional academic. Nor did he write for a scholarly audience. His more than 650 publicaitons are mainly short articles and pamphlets written rather hastily and sometimes republished in collections (Laing, 1979). These must be assembled and organized topically by the reader to gain a sense of Frys overall position on any subject. When this is done, however, it can be seen that often Frys work is systematic and lled with insights that are relevant still to modern theory and practice. Since most of Frys career was involved with one part or another of the art market it is not surprising that he wrote extensively about it. He seems to have had little contact with the professional economics of his time beyond an acquaintance perhaps with Mills Principles, the works of Ruskin on political economy,

44

CRAUFURD D. GOODWIN

and whatever he may have picked up from his close acquaintance with Keynes. Frys writings on the art market reveal his intimate acquaintance with details of market phenomena and with nuances of events that would have been lost on less sophisticated observers. Fry was distinctive among his Bloomsbury friends for applying the methods of science as he understood them to all aspects of life, including the arts and humanities. He searched for generalizations that could be used to explain facts that intrigued him. But he was always careful to employ theory as hypothetical only and subject to test and modication on the evidence. He was fascinated by the very nature of science, and he speculated that it might be closely akin to the creative arts as part of the imaginative life of human beings, following disciplinary rules, by and large, but at the same time advancing in ways that could not be fully understood. Frys reections on the art market began in the 1890s and continued until his death in 1934. Understandably he began his explorations on the supply side where he was himself prominently invloved. What, he asked, made artists create art? Here he took inspiration from Sir Joshua Reynolds Discourses to the Royal Academy which he introduced in a new edition in 1905 (Fry, 1905). Reynolds suggested that principles of order and reason as against caprice and accident should be discoverable to explain the creative imagination. Frys own rst attempt to illuminate these principles of order and reason was An Essay in Aesthetics (1909), reprinted in his collection of essays Vision and Design (Fry, 1920) and probably his best known work. There, and in subsequent writings, Fry suggested that human experience could be divided into two parts: the actual life where biological and instinctive needs and responses prevailed, and an imaginative life where different stimuli operated, notably the love of truth and beauty. The motivation that drove artists on, and the pleasure that they gave to themselves and others, seemed to Fry to be fundamentally different from the utility and disutility that lay beyond calculations and decisions made in labor and consumer goods markets. Fry took from Leo Tolstoy the idea that art is not about the production and exchange of goods that yield utility but about the communication of emotion (Tolstoy [1896], 1960). The motivating force was not pecuniary but was a mysterious aesthetic impulse somewhat akin to, and perhaps derived from, Thorstein Veblens instinct of workmanship (Veblen [1899], 1979). In Frys own terms an artist rst experienced a vision, and then transformed this vision into a design that was an effective vehicle for the communication of aesthetic emotion. He suggested rst, following the Harvard aesthetician Denman Ross, that design, embodying proper attention to both order and variety, was more important than the content of a work of art in determining its effectiveness at communication. Later he accepted the need for a proper balance between form and content. Fry maintained that in any society at any one time there are few artists with the innate capacity to communicate aesthetic emotion successfully and with the impulse to do so. Society had the responsibility to itself to make certain that these

ROGER FRY: ART AND COMMERCE

45

few were adequately nourished and encouraged so that thereby they could enrich the vital imaginative life of the people. This led him naturally from the supply side to the demand side of the market, so as to discover who in a modern market economy is likely to engage in the consumption of art. Fry concluded that the demand for art, in contrast to the biologically-driven demands for goods of the actual life, is socially driven. Through history the most important demands had come from the Church. Then, as the role of religion in the imaginative life of mankind declined, monarchical and aristocratic patrons emerged as replacements on the demand side. By the nineteenth century, however, both the Church and the aristocracy were being displaced by wealthy merchants and manufacturers in the art market. Reecting on the signicance of this shift, Fry was led to publish the pamphlet that is reprinted here. In it, following Thorstein Veblen, with whose work he had presumably become familiar during his residence in New York (19051907), he makes a distinction between what really is the market for art, and what most people think of as the market for art but which he calls the market for opifacts, dened as all objects not for direct use but for the gratication of those special feelings and desires, those various forms of ostentation. Works of art are only a subset of the opifacts produced in any society at any time but the proportion of art to opifacts helps to determine the quality of a civilization. Correspondingly the proportion of artists among the makers of opifacts (the opicers) is a critical determinant of human progress. The relations between artists and the larger community of opicers, most of whom were responding only to demands for goods that would demonstrate conspicuous consumption, were often tense. Yet, Fry observed, deceased artists of great distinction were frequently claimed by opicers as their own and canonized. Living artists were seldom celebrated in this way. Beginning with Art and Commerce, published by his friends Leonard and Virginia Woolf at their Hogarth Press (Fry, 1926a), Fry began an extended exploration of the likely consequences of advanced industrial development for the arts. Mass production, he concluded, was likely to have negative effects, because of the discouragement to spontaneity and the high costs of design changes that put designers out of work. The one compensating benet from industrialization for artists that he could discern came from their employment in the creation of advertising materials. With the Church, the aristocracy, and the modern corporation largely irrelevant in the market for genuine art, Fry asked who remained. In a number of publications written around the same time as Art and Commerce, some of which were republished in his collection entitled Transformations (Fry, 1926) he explored this question in some detail. Any demand for art from the state he found to be generally unsatisfactory because government agencies were driven to action by the herd of voters, most of whom had execrable taste. All that remained on the demand side, then, was the middle class which for analytical purposes he divided into three categories: the snobbists who are driven entirely by fashion, men of culture who purchase only works of dead artists certied by scholars to be of high quality,

46

CRAUFURD D. GOODWIN

and true aesthetes responding to the aesthetic message carried by the work of art. Although the middle-class aesthete was in many places a threatened species, Fry credited it still with providing the necessary impetus for the outpouring of Impressionist and Postimpressionist art in France in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Frys recommendations for public policy in the art market were modest. He was doubtful of the contributions that public education or museums could make either to the demand or the supply side of the art market. He was resolutely opposed to direct public subsidies to artists on the ground that government would usually pick the wrong ones. Frys most condent recommendation was for improvement in competition in the art market. He insisted upon elimination of corruption and conspiracy in restraint of trade, and he held out high hopes for achieving these goals from the efforts of fearless investigatory art critics such as himself. He favored experimentation with different kinds of economic units for the production and sale of art so as to provide secure employment for artists while recognizing their particular characteristics and human foibles. His own Omega Workshops was a bold experiment of this kind that offered a guaranteed minimum income to participants (Collins, 1983). It required anonymity among the artists so that rents that might accrue could be shared among the entire community and so that artists who came suddenly into fashion would not be corrupted by fame and fortune. Frys observations of the fate of the artist in the new Soviet state (Fry, 1920) only strengthened his conviction that hope for the artist over the long run lay in a democracy with a competitive market economy and a broadly educated and aesthetically-sensitive middle class able to sustain the market demand for art. His own efforts to move British society in this direction included a prominent role with John Maynard Keynes and others in the Contemporary Art Society, which aimed to get ne art widely distributed among the citizenry, and close association with Leonard and Virginia Woolf in the Hogarth Press, an attempt to restore aesthetic values to a publishing industry that seemed to have succumbed almost entirely to mass production. The pamphlet Art and Commerce which follows was not Frys crowning work on the art market. There is no such work. He had no grand research program on this topic in which this could be seen even as a building block. He wrote when he felt like it, inspired by his reading, his conversations, events in his life, and questions he wanted answered. This work, published by his friends the Woolfs, was originally a lecture on posters, which he perceived as an artistic by-product of advertising in a market economy. This essay is more carefully constructed than some of his writings, but note still the mistake in the title of Veblens great work. At least fty of Frys writings contain valuable comment on economic topics. A selection of these works, with an interpretation, will be published later this year by the University of Michigan Press under the title Art and the Market: Roger Fry on the Commerce in Art .

ROGER FRY: ART AND COMMERCE

47

References

Collins, Judith (1983) The Omega Workshops. Secker and Warburg, London. Fry, Roger (1905) Discourses Delivered to the Students of the Royal Academy by Sir Joshua Reynolds, with Introduction and Notes by Roger Fry. Seeley and Co., London. Fry, Roger (1920) Bolshevik Art. Athenaeum (13 August): 216217. Fry, Roger ([1920] 1956) Vision and Design. Meridian, New York. Fry, Roger (1926) Transformations: Critical and Speculative Essays on Art. Chatto and Windus, London. Fry, Roger (1926a) Art and Commerce. Hogarth Press, London. Laing, Donald A. (1979) Roger Fry: An Annotated Bibliography of his Published Writings. Garland, New York. Rosenbaum, S. P. (1964) Edwardian Bloomsbury. St Martins Press, New York. Spalding, Frances (1980) Roger Fry: Art and Life. University of California Press, Berkeley and Los Angeles. Tolstoy, Leo N. ([1896] 1960) What is Art? Liberal Arts Press, Macmillan, New York. Veblen, Thorstein ([1899] 1979) Theory of the Leisure Class. Penguin Books, New York. Woolf, Virginia ([1940] 1976) Robert Fry: A Biography, Harvest edition. Harcourt Brace, New York.

Você também pode gostar

- After the End of Art: Contemporary Art and the Pale of History - Updated EditionNo EverandAfter the End of Art: Contemporary Art and the Pale of History - Updated EditionNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (26)

- Alloway Lawrence 1962 2004 Pop Since 1949Documento13 páginasAlloway Lawrence 1962 2004 Pop Since 1949Amalia WojciechowskiAinda não há avaliações

- Introduction: "Pop Since 1949": Nigel WhiteleyDocumento13 páginasIntroduction: "Pop Since 1949": Nigel WhiteleyMilica Amidzic100% (1)

- Linda BenglysDocumento14 páginasLinda BenglysClaudiaRomeroAinda não há avaliações

- RomanticismDocumento31 páginasRomanticismapi-193496952100% (1)

- LFM PresentationDocumento3 páginasLFM PresentationFor YouAinda não há avaliações

- Chapter 3 Art Sentence OutlineDocumento8 páginasChapter 3 Art Sentence OutlineRomar PogoyAinda não há avaliações

- Realism N DadaismDocumento13 páginasRealism N Dadaismkatelybabe0% (1)

- Atestat EnglezaDocumento17 páginasAtestat EnglezaBob Cu PunctAinda não há avaliações

- RomanticismDocumento8 páginasRomanticismVioleta ComanAinda não há avaliações

- Abject Sexuality in Pop ArtDocumento8 páginasAbject Sexuality in Pop ArtGris ArvelaezAinda não há avaliações

- Blooms Bury - Fry - C Bell - & Chinese ArtDocumento43 páginasBlooms Bury - Fry - C Bell - & Chinese ArtpillamAinda não há avaliações

- NullDocumento4 páginasNullDanish AliAinda não há avaliações

- Whiteley 2001 Reyner Banham Historian of The Immediate Future PDF (102 161)Documento60 páginasWhiteley 2001 Reyner Banham Historian of The Immediate Future PDF (102 161)MarinaAinda não há avaliações

- Orwell Art and PropagandaDocumento5 páginasOrwell Art and PropagandaMarcusFelsman100% (1)

- Pop ArtDocumento8 páginasPop ArtsubirAinda não há avaliações

- Enough With Pop Art: Giulia SmithDocumento6 páginasEnough With Pop Art: Giulia SmithRafael Iwamoto TosiAinda não há avaliações

- Marc Lowenthal, Translator's Introduction To 'Si: Francis PicabiaDocumento3 páginasMarc Lowenthal, Translator's Introduction To 'Si: Francis PicabiaAndrew Wayne Flores0% (1)

- Art For Art SakeDocumento3 páginasArt For Art SakeRubab ChaudharyAinda não há avaliações

- History of English Assignment 1st PDFDocumento22 páginasHistory of English Assignment 1st PDFHassan JavedAinda não há avaliações

- Pop ArtDocumento11 páginasPop ArtAgus Rodriguez100% (1)

- Target Audience of Pop ArtDocumento2 páginasTarget Audience of Pop Artapi-264140833Ainda não há avaliações

- Gale Researcher Guide for: The Arts and Scientific Achievements between the WarsNo EverandGale Researcher Guide for: The Arts and Scientific Achievements between the WarsAinda não há avaliações

- Huyssen, A. - Avantgarde and PostmodernismDocumento19 páginasHuyssen, A. - Avantgarde and PostmodernismMónica AmievaAinda não há avaliações

- Abstraction and Empathy: A Contribution to the Psychology of StyleNo EverandAbstraction and Empathy: A Contribution to the Psychology of StyleAinda não há avaliações

- Richard BergDocumento12 páginasRichard BergSiddhartha Della SantinaAinda não há avaliações

- Pop ArtDocumento24 páginasPop ArtCorina MariaAinda não há avaliações

- ModernismDocumento2 páginasModernismTanmoy RajbanshiAinda não há avaliações

- Art For Truth SakeDocumento16 páginasArt For Truth Sakehasnat basir100% (1)

- YONATAN TEWELDE, Yasar University. Faculty of Communication: DadaismDocumento6 páginasYONATAN TEWELDE, Yasar University. Faculty of Communication: DadaismNailArtMuseAinda não há avaliações

- October's PostmodernismDocumento12 páginasOctober's PostmodernismDàidalos100% (1)

- Twentieth Century and ModernismDocumento24 páginasTwentieth Century and Modernismφελίσβερτα ΩAinda não há avaliações

- Pop ArtDocumento8 páginasPop Artapi-193496952Ainda não há avaliações

- Make Up DiscussionsDocumento3 páginasMake Up DiscussionsBarut Shaina TabianAinda não há avaliações

- Important Modern Ismss Modern Prose Writings 1 1629365083324Documento119 páginasImportant Modern Ismss Modern Prose Writings 1 1629365083324Ananya SinghAinda não há avaliações

- Avant GardeDocumento8 páginasAvant Gardealbert Dominguez100% (1)

- Realism Versus Realism in British Art of The 1950s: Juliet SteynDocumento13 páginasRealism Versus Realism in British Art of The 1950s: Juliet SteynMarcos Magalhães RosaAinda não há avaliações

- Is Art Criticism in A Crisis Master ThesDocumento96 páginasIs Art Criticism in A Crisis Master ThesMarina ErsoyAinda não há avaliações

- Arte Sacro FuturistaDocumento41 páginasArte Sacro FuturistaLauCabezasAinda não há avaliações

- Art Rules Pierre Bourdieu The Visual Arts PDFDocumento225 páginasArt Rules Pierre Bourdieu The Visual Arts PDFDheyby Yolimar Quintero SiviraAinda não há avaliações

- Lec 9Documento3 páginasLec 9Ubaid KhanAinda não há avaliações

- Bronzino's Martyrdom of St. Lawrence & Counter Reformation PDFDocumento23 páginasBronzino's Martyrdom of St. Lawrence & Counter Reformation PDFde-kAinda não há avaliações

- Anti Modernism EssayDocumento3 páginasAnti Modernism EssayAndrew MunningsAinda não há avaliações

- SG Art, Music, Literature/Social History 1450-2000Documento5 páginasSG Art, Music, Literature/Social History 1450-2000smbajwaAinda não há avaliações

- Antliff, Mark. ''Fascism, Modernism, and Modernity'' PDFDocumento23 páginasAntliff, Mark. ''Fascism, Modernism, and Modernity'' PDFiikAinda não há avaliações

- 2011 - Art History - Rahtz - The Artist As WorkerDocumento3 páginas2011 - Art History - Rahtz - The Artist As WorkerManuel CirauquiAinda não há avaliações

- Reviewof Kelly Encyclopediaof AestheticsDocumento14 páginasReviewof Kelly Encyclopediaof AestheticsSosiAinda não há avaliações

- Structural Criticism: We Started This Course With A Discussion of What Art Is. That Discussion WasDocumento3 páginasStructural Criticism: We Started This Course With A Discussion of What Art Is. That Discussion Waslara camachoAinda não há avaliações

- HH Arnason - Abstract Expressionism and The New American Art (Ch. 19)Documento36 páginasHH Arnason - Abstract Expressionism and The New American Art (Ch. 19)KraftfeldAinda não há avaliações

- Francis Haskell, Art and The Language of Politics, Journal of European Studies 1974 Haskell 215 32Documento19 páginasFrancis Haskell, Art and The Language of Politics, Journal of European Studies 1974 Haskell 215 32meeeemail5322Ainda não há avaliações

- Modernist Abstraction, Anarchist Anti Militarism, and WarDocumento39 páginasModernist Abstraction, Anarchist Anti Militarism, and WarAtosh KatAinda não há avaliações

- Introduction: Dada, Surrealism, and ColonialismDocumento8 páginasIntroduction: Dada, Surrealism, and ColonialismDorota MichalskaAinda não há avaliações

- Pop ArtDocumento9 páginasPop ArtGuzel AbdrakhmanovaAinda não há avaliações

- Daros Latinamerica Memories BehindDocumento32 páginasDaros Latinamerica Memories BehindGuillermo VillamizarAinda não há avaliações

- Y1 - Modernism in IrelandDocumento20 páginasY1 - Modernism in IrelandBrendan Joseph MaddenAinda não há avaliações

- Art in The 1960sDocumento19 páginasArt in The 1960scara_fiore2Ainda não há avaliações

- Pierre Bourdieu, Hans HaackeDocumento78 páginasPierre Bourdieu, Hans HaackeClaudiaRomeroAinda não há avaliações

- Sherwin Simmons, Chaplin Smiles On The Wall - Berlin Dada and Wish-Images of Popular CultureDocumento33 páginasSherwin Simmons, Chaplin Smiles On The Wall - Berlin Dada and Wish-Images of Popular CultureMBAinda não há avaliações

- CAA The Art Bulletin: This Content Downloaded From 131.196.210.253 On Wed, 10 Aug 2022 12:14:23 UTCDocumento28 páginasCAA The Art Bulletin: This Content Downloaded From 131.196.210.253 On Wed, 10 Aug 2022 12:14:23 UTCJuan CarlosAinda não há avaliações

- Ge 404 - Tutorial 1 1Documento10 páginasGe 404 - Tutorial 1 1Riad El AbedAinda não há avaliações

- Vantive API: Reference GuideDocumento211 páginasVantive API: Reference Guidechechu_sg100% (1)

- Look, Read and Circle.: Kelly John MaryDocumento3 páginasLook, Read and Circle.: Kelly John MaryJazmin Bendezu PeñaAinda não há avaliações

- Library Binding Can Be Divided Into TheDocumento3 páginasLibrary Binding Can Be Divided Into TheNirmal BhowmickAinda não há avaliações

- Using Postgis/Postgresql For Managing Cad and Gis DataDocumento18 páginasUsing Postgis/Postgresql For Managing Cad and Gis DatatsimencAinda não há avaliações

- Fomrhi 110Documento88 páginasFomrhi 110Gaetano PreviteraAinda não há avaliações

- Unsitely Maria MirandaDocumento157 páginasUnsitely Maria MirandaIsabelaAinda não há avaliações

- Bill ViolaDocumento13 páginasBill ViolaNick Savidge100% (1)

- There Is / There e / Is There / Re ThereDocumento2 páginasThere Is / There e / Is There / Re ThereCamilo LópezAinda não há avaliações

- h3d API ManualDocumento57 páginash3d API ManualNathalie Cañon ForeroAinda não há avaliações

- The Merciad, April 25, 1996Documento12 páginasThe Merciad, April 25, 1996TheMerciadAinda não há avaliações

- Before Listening: Finding The LibraryDocumento4 páginasBefore Listening: Finding The Librarytomas rAinda não há avaliações

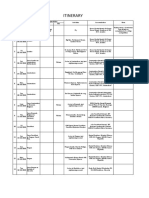

- 25 Days in Europe Itinerary1Documento22 páginas25 Days in Europe Itinerary1Ega ErlanggaAinda não há avaliações

- Care, Compassion, Excellence Mount Lockyer Primary School A Place To Learn and GrowDocumento4 páginasCare, Compassion, Excellence Mount Lockyer Primary School A Place To Learn and GrowMountLockyerAinda não há avaliações

- Handout 6751 SD6751 Ambrosius PDFDocumento31 páginasHandout 6751 SD6751 Ambrosius PDFedwin154Ainda não há avaliações

- Man Eng Mov11.3 Movicon Vba LanguageDocumento1.260 páginasMan Eng Mov11.3 Movicon Vba LanguagemsciricAinda não há avaliações

- Verbal Linguistic Wordsmart Presentation3dDocumento2 páginasVerbal Linguistic Wordsmart Presentation3dapi-297339950Ainda não há avaliações

- SimCity Exception Report 2014.03.24 09.33.06Documento3 páginasSimCity Exception Report 2014.03.24 09.33.06Adah Gwynne TobesAinda não há avaliações

- Amsterdam enDocumento23 páginasAmsterdam enCosstyAinda não há avaliações

- Read UK: Graffiti: Art or Vandalism? - Exercises: PreparationDocumento2 páginasRead UK: Graffiti: Art or Vandalism? - Exercises: PreparationSofiamarcAinda não há avaliações

- Skin Two MagazineDocumento3 páginasSkin Two MagazineJennifer Oswalt Rosario36% (14)

- Answer in ShortDocumento87 páginasAnswer in Shortapi-19920737Ainda não há avaliações

- Red Queen by Michael BagenDocumento55 páginasRed Queen by Michael BagenkarlorrocksAinda não há avaliações

- Marketing: Making A Case For Your Library: (Reprinted For This Workshop by Permission of The Author)Documento6 páginasMarketing: Making A Case For Your Library: (Reprinted For This Workshop by Permission of The Author)PonsethuAinda não há avaliações

- Sipovskij V V Iz Istorii Russkogo Romana I Povesti 01 XVIII Vek 1903Documento370 páginasSipovskij V V Iz Istorii Russkogo Romana I Povesti 01 XVIII Vek 1903brankovranesAinda não há avaliações

- Bernini Sculpting in Clay PDFDocumento434 páginasBernini Sculpting in Clay PDFAmitabh Julyan89% (9)

- Creatia Lui Carl CzernyDocumento9 páginasCreatia Lui Carl CzernyMarcela NeaguAinda não há avaliações

- Louisburg Log Cabin MuseumDocumento8 páginasLouisburg Log Cabin MuseumCharles PurvisAinda não há avaliações

- Bbiblio ElectroblioDocumento732 páginasBbiblio ElectroblioratatuAinda não há avaliações

- Exhibition Review: Maison Martin Margiela "20" The ExhibitionDocumento10 páginasExhibition Review: Maison Martin Margiela "20" The Exhibitionvitor santannaAinda não há avaliações