Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

FinishingtheJob

Enviado por

AACS Co-repTítulo original

Direitos autorais

Formatos disponíveis

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

FinishingtheJob

Enviado por

AACS Co-repDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Finishing the job: Delivering a bullet-proof ATT

Summary At the end of the consensus-based negotiation process in the July 2012 Diplomatic Conference for the Arms Trade Treaty, states failed to agree a treaty. A draft treaty text was produced that contains many of the elements necessary for effective control of the international arms trade. However, this text also contains a number of weaknesses and loopholes that threaten fundamentally to undermine its effectiveness. As statements throughout the negotiations demonstrated, the majority of states want to see a robust treaty agreed. The Arms Trade Treaty is too important for any one state to be able to wield a veto. It is the voices of the overwhelming majority of states that want a strong treaty which must be heard in the next steps in the process, rather than the minority of states that do not support the aims and objectives set out by UN General Assembly Resolution 64/48 in 2009. Given that the July 2012 DipCon was unable to produce agreement by consensus any decision to hold a follow-up conference on the same basis runs the risk of repeating this failure.

Introduction

The July 2012 Diplomatic Conference (DipCon) for the Arms Trade Treaty (ATT) was intended as the concluding part of the UN ATT process, which formally began in 2006. After a month of detailed negotiations, a draft treaty text was presented on the penultimate day of the DipCon. Despite the desire of most states to see the treaty concluded, on the final day, the United States asked for more time to consider the text, thereby blocking a consensus outcome. Despite this setback, there is now widespread support to deliver a treaty in early 2013 by building upon the outcomes of the July 2012 negotiations. While it is encouraging that states have proved willing to harness the momentum of the final days of the July DipCon, it is worrying that many states appear prepared to see the next stage in the process bound by the consensus decision-making rule. This presents a significant risk of the next stage in the process merely repeating the failure of the previous, or producing a very weak text. States need to safeguard an effective and productive process by allowing for the possibility of a vote if all feasible attempts to achieve consensus fail. The draft text of 26 July 2012 contains many of the basic elements needed for effective control of the global arms trade, including: An obligation on arms-exporting states to conduct comprehensive risk assessments in line with international human rights and humanitarian law before approving international transfers of arms; A clear recognition that there are circumstances whereby transfers of arms should never be allowed, e.g. where weapons would be used to violate states international obligations; A scope that includes small arms and light weapons (SALW), which are responsible for the largest proportion of deaths from armed violence; A requirement that states report on their arms transfers and on steps that they take to implement the treaty; Positive provisions relating to record-keeping, international assistance, and implementation of the treaty; and The establishment of a Secretariat to assist signatories in implementing the treaty. 1

Closing the loopholes

However the current draft text has a number of problems and loopholes that would undermine its ability to adequately address the humanitarian and human rights problems fuelled by the poorly regulated international arms trade. Many of these were still being negotiated during the last hours of the July DipCon, when there appeared to be considerable resolve in favor of finding workable solutions so that a robust outcome could be achieved. These loopholes include but are not limited to the following: Article 2: The Scope of the draft treaty is too narrow: The draft treaty only includes arms that fall under the seven categories of major offensive conventional weapons covered by the UN Register of Conventional Arms plus SALW. This means that many types of conventional weaponsincluding armored troop-carrying vehicles and helicoptersare not controlled. Ammunition and munitions, parts and components are also missing from the scope section of the text, so transfers of these items are subject to less stringent control and are exempt from record-keeping and reporting requirements. Article 2: The draft treaty should provide much greater clarity regarding what constitutes an international transfer of arms: Current references to international transfers are conflated with definitions of the international trade in arms and are opaque and confusing; this could lead to states interpreting differently their obligations within the treaty. Article 3: Prohibitions relating to arms for genocide, crimes against humanity and war crimes are too narrowly applied: The current wording presumes an intent on the part of the supplying state that the weapons be used to commit prohibited acts, which would already place that state far beyond the bounds of international law and acceptability. Moreover, the range of war crimes to which even these provisions apply is far too narrow and excludes, for example, deliberate attacks on civilian populations. Article 4: The threshold for risk assessment of human rights and humanitarian law violations and for commission of terrorist acts is unclear: The draft treaty sets a threshold of overriding risk that states could interpret as requiring the refusal of a transfer only in extreme and exceptional circumstances. Article 4.6: Provisions concerning diversion, corruption, development, and gender-based violence are weak: The draft treaty does not require states to consider risks relating to diversion, corruption, development and gender-based violence as part of the grounds for refusing an international arms transfer. Article 5.2: Exemptions created by language on other instruments and defence cooperation agreements are very problematic: The assertion that the implementation of the treaty should not prejudice obligations with regard to other instruments could allow states to enter into agreements that undermine the treaty. There is also nothing to prevent States classifying all of their international arms trading operations as defence cooperation agreements thereby circumventing the treatys provisions. 2

Article 10: Reporting requirements will do little to enhance transparency in the international arms trade: The draft treaty makes no explicit provision for public reporting and, because of the narrow definition of scope, exempts reporting on ammunition and parts and components transfers. Exemptions for national security and commercially sensitive data pose the risk that states will withhold vital information even from the secretariat and other states parties. Article 16: Entry into Force (EIF) requirement of 65 is too high: This means that it could be many years before the treaty can enter into force; a requirement for 30 states to ratify for EIF is the practice under some other instruments and would be more appropriate for the ATT. Article 20: Strengthening the treaty over time will be very difficult: Decisions regarding amendments to the treaty will need to be taken by consensus, making it extremely hard to improve the treaty in future. Article 23: The possible absence of controls on certain transfers to states not-party to the treaty: This article is ambiguous with regard to the application of treaty obligations to states not party to the treaty. It asserts only that Articles 3 and 4 should apply to international transfers to non-party states of conventional arms under the scope of the treaty. This suggests, for example, that there would be no controls on international transfers of ammunition and parts and components to non-party states.

The humanitarian objective

Ultimately, the ATT will be judged according to its success in preventing arms transfers that risk contributing to or facilitating human suffering. An ATT that does not serve to enhance human security will represent a hollow victory for all those who have advocated for a robust treaty. If the above-cited exemptions and loopholes remain, then there is a serious risk that irresponsible and illegal transfers of weapons will continue to fuel conflict, armed violence and human rights abuses around the world. In particular, if ammunition is absent from the scope of the treaty and obligations to address diversion risks remain inadequate, the treaty will fail to live up to the hopes of the millions of people threatened by armed groups around the world who currently have easy access to the weapons and ammunition they need to continue waging war. Moreover, the defence cooperation agreement exemption would provide legal protection for irresponsible arms transfers of the kind seen between Russia and Syria throughout 2012. These transfersincluding the servicing and upgrade of attack helicoptershave been conducted under the guise of fulfilling existing contractual obligations. The loophole in the draft text would potentially legitimize and provide cover for such claims.

Você também pode gostar

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryNo EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (231)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)No EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Nota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (120)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaNo EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (266)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingNo EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (399)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItNo EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (838)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerNo EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (271)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeNo EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (5794)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyNo EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (2259)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersNo EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (344)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnNo EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (234)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreNo EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (1090)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceNo EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (895)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureNo EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (474)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaNo EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (45)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)No EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Nota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (98)

- Bench Guidelines and PoliciesDocumento3 páginasBench Guidelines and PoliciesEscalation ACN Whirlpool50% (2)

- Hijo Plantation V Central BankDocumento3 páginasHijo Plantation V Central BankAiken Alagban LadinesAinda não há avaliações

- Case 32Documento2 páginasCase 32Dianne Macaballug100% (1)

- Kho V CADocumento1 páginaKho V CAAlexandraSoledadAinda não há avaliações

- Tulabing V MST MarineDocumento3 páginasTulabing V MST MarineHencel GumabayAinda não há avaliações

- LC DigestDocumento34 páginasLC DigestJuvylynPiojoAinda não há avaliações

- 619-Valdez Vs TabisulaDocumento1 página619-Valdez Vs Tabisula001nooneAinda não há avaliações

- L11 - ATTresolutionDocumento2 páginasL11 - ATTresolutionAACS Co-repAinda não há avaliações

- ATTJoint StatementDocumento2 páginasATTJoint StatementAACS Co-repAinda não há avaliações

- 20130320ATTDraft PresidentNonPaperDocumento13 páginas20130320ATTDraft PresidentNonPaperAACS Co-repAinda não há avaliações

- 20130322ATTDraft PresidentNonPaperDocumento13 páginas20130322ATTDraft PresidentNonPaperAACS Co-repAinda não há avaliações

- NGO StatementDocumento3 páginasNGO StatementAACS Co-repAinda não há avaliações

- United Nations Arms Trade TreatyDocumento15 páginasUnited Nations Arms Trade TreatyDowning Post NewsAinda não há avaliações

- Consultation PAPER Implementation 2Documento3 páginasConsultation PAPER Implementation 2AACS Co-repAinda não há avaliações

- Consultation PAPER PreamblePrinciplesDocumento3 páginasConsultation PAPER PreamblePrinciplesAACS Co-repAinda não há avaliações

- Draft ("Final") Text 26 JulyDocumento11 páginasDraft ("Final") Text 26 JulyDanBenLee100% (2)

- Consultation PAPER Final ProvisionsDocumento4 páginasConsultation PAPER Final ProvisionsAACS Co-repAinda não há avaliações

- Consultation PAPER CriteriaDocumento1 páginaConsultation PAPER CriteriaAACS Co-repAinda não há avaliações

- PAPER Scope NewDocumento1 páginaPAPER Scope NewAACS Co-repAinda não há avaliações

- Draft Text 24 JulyDocumento12 páginasDraft Text 24 JulyDanBenLeeAinda não há avaliações

- Consultation PAPER Implementation 2Documento3 páginasConsultation PAPER Implementation 2AACS Co-repAinda não há avaliações

- Consultation PAPER Goals and ObjectivesDocumento1 páginaConsultation PAPER Goals and ObjectivesAACS Co-repAinda não há avaliações

- Consultation PAPER ScopeDocumento1 páginaConsultation PAPER ScopeAACS Co-repAinda não há avaliações

- Consultation PAPER Implementation 1Documento3 páginasConsultation PAPER Implementation 1AACS Co-repAinda não há avaliações

- PAPER Implementation1Documento3 páginasPAPER Implementation1AACS Co-repAinda não há avaliações

- PAPER Implementation2Documento1 páginaPAPER Implementation2AACS Co-repAinda não há avaliações

- PAPER Implementation3Documento2 páginasPAPER Implementation3AACS Co-repAinda não há avaliações

- PAPER2 Criteria ParametersDocumento2 páginasPAPER2 Criteria ParametersAACS Co-repAinda não há avaliações

- PAPER Criteria Parameters ImplementationDocumento2 páginasPAPER Criteria Parameters ImplementationAACS Co-repAinda não há avaliações

- Statement On Behalf ofDocumento2 páginasStatement On Behalf ofControl ArmsAinda não há avaliações

- PAPER CtiretiaDocumento2 páginasPAPER CtiretiaAACS Co-repAinda não há avaliações

- PAPER Goals ObjectivesDocumento1 páginaPAPER Goals ObjectivesAACS Co-repAinda não há avaliações

- PAPER Preamble PrinciplesDocumento2 páginasPAPER Preamble PrinciplesAACS Co-repAinda não há avaliações

- PAPER Final ProvisionsDocumento4 páginasPAPER Final ProvisionsAACS Co-repAinda não há avaliações

- PAPER ImplementationDocumento7 páginasPAPER ImplementationAACS Co-repAinda não há avaliações

- Paper IsuDocumento1 páginaPaper IsuAACS Co-repAinda não há avaliações

- 53 Goquiolay V Sycip (Resolution)Documento13 páginas53 Goquiolay V Sycip (Resolution)slumbaAinda não há avaliações

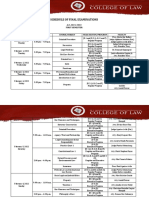

- 1st Sem 2021 22 Finals ScheduleDocumento5 páginas1st Sem 2021 22 Finals ScheduleRyan ChristianAinda não há avaliações

- IN-Sen: Trafalgar Group (R) (August 2018)Documento28 páginasIN-Sen: Trafalgar Group (R) (August 2018)Daily Kos ElectionsAinda não há avaliações

- Company Law Made Easy Quick Revision PDFDocumento44 páginasCompany Law Made Easy Quick Revision PDFMuhammad Hamdi Tahir Amin CHAinda não há avaliações

- Dear ColleagueDocumento3 páginasDear ColleaguePeter SullivanAinda não há avaliações

- Conflictofinterest AGDocumento204 páginasConflictofinterest AGbonecrusherclanAinda não há avaliações

- Internship Report by Vamsi KrishnaDocumento7 páginasInternship Report by Vamsi KrishnaManikanta MahimaAinda não há avaliações

- 2016-2017 Statcon Final SyllabusDocumento18 páginas2016-2017 Statcon Final SyllabusTelle MarieAinda não há avaliações

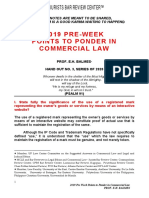

- 2019 Pre-Week Points To Ponder in Commercial Law by Prof. Erickson BalmesDocumento11 páginas2019 Pre-Week Points To Ponder in Commercial Law by Prof. Erickson BalmesMate LuquinganAinda não há avaliações

- Labour Law Notes GeneralDocumento55 páginasLabour Law Notes GeneralPrince MwendwaAinda não há avaliações

- 214 Spouses Lam v. Kodak Phils., Ltd.Documento1 página214 Spouses Lam v. Kodak Phils., Ltd.VEDIA GENONAinda não há avaliações

- Stephen D. Gardner Chief Counsel: Commercial Law Development ProgramDocumento14 páginasStephen D. Gardner Chief Counsel: Commercial Law Development ProgramxcygonAinda não há avaliações

- A Pongo L Final EditedDocumento3 páginasA Pongo L Final EditedMarq QoAinda não há avaliações

- The Difference Between Auditors and Forensic AccountantsDocumento1 páginaThe Difference Between Auditors and Forensic AccountantsMohammed MickelAinda não há avaliações

- General Exceptions To IPCDocumento14 páginasGeneral Exceptions To IPCNidhi SinghAinda não há avaliações

- Full Download Test Bank For Life Span Development 13th Edition Santrock PDF Full ChapterDocumento36 páginasFull Download Test Bank For Life Span Development 13th Edition Santrock PDF Full Chapterrecanter.kymneli72p100% (14)

- White Paper On Indian States (1950)Documento794 páginasWhite Paper On Indian States (1950)VIJAYAinda não há avaliações

- As365-Ec155-Sa365 2021-03-06Documento7 páginasAs365-Ec155-Sa365 2021-03-06chiri003Ainda não há avaliações

- Montelius AffidavitDocumento6 páginasMontelius Affidavitkaimin.editorAinda não há avaliações

- Fed. Drug IndictmentsDocumento16 páginasFed. Drug IndictmentsChewliusPeppersAinda não há avaliações

- State Vs LegkauDocumento9 páginasState Vs LegkauJei Essa AlmiasAinda não há avaliações

- When It Is Legal To Put An Employee On Floating Status - HR Practitioner's GuideDocumento2 páginasWhen It Is Legal To Put An Employee On Floating Status - HR Practitioner's GuidemereselAinda não há avaliações

- Capital Ins. & Surety Co., Inc. vs. SadangDocumento6 páginasCapital Ins. & Surety Co., Inc. vs. SadangToni LorescaAinda não há avaliações