Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

Writing For Impact: Lessons From Journalism

Enviado por

OxfamTítulo original

Direitos autorais

Formatos disponíveis

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Writing For Impact: Lessons From Journalism

Enviado por

OxfamDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

www.oxfam.org.

uk/policyandpractice

WRITING FOR IMPACT: LESSONS FROM JOURNALISM

WHY MASTER THIS SKILL ?

Most of us obtain most of our information about what is going on in the world from some form of journalism listening to the news on the radio, reading a newspaper, watching the TV or increasingly, from citizens journalism like Twitter. We are so used to hearing or seeing news stories that we may not realise that they are cleverly constructed and usually in a particular way. It is the way journalists are taught to communicate, and it is clearly influential. If we wish to have maximum impact when communicating our research findings then we can learn a lot by understanding how journalists package the information they gather. There is a general inverse relationship between the amount of facts and the complexity of the information to be provided and the communicability of the information. The more information, the less likely it is that readers or listeners will absorb it all. However, by using journalistic techniques you may be surprised at how much information you can convey to people.

RESEARCH GUIDELINES

WHAT ARE THE TECHNIQUES USED BY JOURNALISTS?

The basis of any piece of journalism is to tell who did what to whom, when, where, how and why, and with what consequences. That is the actual sequence in which most news stories are told. That sequence is how stories have been told by humans from time immemorial, and journalism exploits the power of story-telling to communicate information. It explains what happened in a way, and in language, that most people can understand. There are four key techniques: Tell stories Keep it as brief as you can Use plain language Structure your report for impact

TELL STORIES

What is a story, and why are stories important? Stories are as old as humanity indeed, it may be that the ability to tell stories are the one and only unique distinguishing mark that separates humanity from other animals. Stories are generally told in a particular way a sequence: who did what to whom, when, where, how and why and with what consequences, and usually they revolve around actions outside the usual frame of reference of the reader or listener. Stories are always about living beings, whether humans, divinities or animals creatures with whom we the reader or hearer can identify. Stories are exciting: they engage the reader at an emotional as well as an intellectual level, which is why they are so memorable and can have such a powerful impact. They invite the reader or hearer to participate in the story by using her imagination so that they become involved with the fate of the protagonists. Stories surprise the reader, they make her or him want to read or listen to the end and they invite him or her to repeat the story to their friends. Stories will probably be remembered long after we have forgotten abstract facts and figures. So for Oxfam, whatever we write or broadcast should always be about people; what are people with whom we work doing, how are they affected, what are their names, their faces, their opinions, concerns in other words, their stories. Even very abstract briefings that need to be full of facts and statistics should always explain at some stage what have all those facts and statistics got to do with real people.

KEEP IT AS BRIEF AS YOU CAN

Why is brevity a useful discipline? Think about the way in which stories are communicated on the radio, TV or in newspapers. You will notice that news stories are generally quite short, in order to keep the viewers attention and in order to cram more news stories into the time or space available. News headlines on the radio may be only 30, 20 or even 10 seconds long. Reading a newspaper story is unlikely to take longer than two or three minutes. Many interviews on news channels are two or three minutes long, no more. Brevity is an important communications strategy because it is about boiling a story down to its absolute essentials. It makes us think about what is the essential piece of information that I want to communicate to my reader or listener, and how can I communicate that best so that it makes an impression on him or her. Having to boil down our research to perhaps one essential fact is not unreasonable if we think of our own lives and how we digest news. We wake up and the radio is on but we are half awake, the baby is crying, we are in a hurry to leave for work, we are trying to have breakfast so though the radio is on we are probably only going to be absorbing one fact per story

the headline and it will take something quite compelling and out of the ordinary to really grab our attention so that we actually listen attentively. So think, how would you explain your research findings to your partner or friend over breakfast in those circumstances? It has to be short, simple and unusual. It follows that you should not cite 10 facts when one will do, and you only need to use one telling example, not five. And to make the fact stick, you should say what it means to a person or family briefly tell the human story.

USE PLAIN LANGUAGE

It follows that we have to talk to people in language that they understand in order to communicate so keep your language simple. Use ordinary words and familiar terms. Avoid jargon and acronyms. Imagine how you would explain your argument to a relative who doesnt know much about Oxfam or what you do for Oxfam and who is likely to be slightly sceptical.

STRUCTURE YOUR REPORT FOR IMPACT

Most news stories have a particular structure. We are so used to the way news is presented that we may not notice the underlying structure but you can easily observe this if you analyse a newspaper. The structure is dictated by the need to grab a readers attention, and by the need for brevity. A news story can look rather like a pyramid. This is how it is usually conventionally represented (this is from Wikipedia):

Note though that in terms of the SIZE of the text that is written, this inverted pyramid is actually exactly the opposite of what we see in a newspaper or magazine. In practice a news story looks more like a pyramid the right way up the first paragraph (the top of the pyramid) is essentially the entire story in miniature as it contains all the facts (what happened i.e. who did what to whom, when, where). The second part expands on this with more background information usually why something happened. The remaining paragraphs expand on the story, perhaps with the implications i.e. what is this likely to mean. But if you only read the first couple of paragraphs, you would know the essential story.

So the way to think of writing a story is better represented like this the most important facts come first and they go into what is actually the smallest space:

Most newsworthy information must have! What happened? i.e. Who? What? When? Where? How?

Important details especially why this happened

General + background information + speculation about implications

Writing in this way and thinking in this way is actually quite a discipline to learn and is not necessarily natural. In fact it is the opposite of the way that one would tell a joke, or even tell a story to friends. To tell a joke you would first set out the scene then say what happened and finally deliver the punch line. The listener doesnt know what happened until the end. In news, you almost do the opposite; the punch line comes at the very beginning, the rest is an expanded explanation of why that thing happened. The reason for this is that if another, bigger story came in to the news desk, and your story had to be cut to accommodate it, the editor would usually cut your story from the bottom up, on the grounds that the least essential information was near the bottom. In the end the whole story could be cut except the first paragraph or two, and yet the essential facts would still be intact in brief. Some people, especially in research and academia, find it hard to adopt a journalistic style of constructing a story. They are taught to make a linear argument, setting out the whole scene first, finally culminating in a conclusion. This is perfectly valid, but the way in which a journalist would communicate the report would be to go straight to the conclusions and state them in the first paragraph of the news story. Thinking what is the key fact or conclusion that I really want to communicate in my report, and setting it out at the beginning, is useful discipline. So any research report should have at the beginning an executive summary - and maybe an abstract, which is an even shorter version of the executive summary- which sets out simply and clearly and up-front what is the essential finding of the report and the basic argument that it is making. Some of your audience (particularly perhaps politicians) will probably only read your executive summary; much as you would like them to read your entire report, they only have time (or inclination) for the essentials. In fact, it is good to write the executive summary of your report first, not write the report and then attempt to summarise it. By doing it this way round you will know clearly what the core argument is and the report itself should just be an expansion of each part of your executive summary.

ALLOW ENOUGH TIME

The purpose of research is to have impact to create change, and that cannot happen without effective communication of the results. But the time needed for effective communication to prepare it and to do it is not always factored into research timetables. Time must clearly be allowed for sign-off but many other people then have jobs to do to disseminate any report. They include editors, designers, printers and publishers, including those people who have to get the report into the right format to go on websites. Finally, the media team are responsible for gaining the attention of journalists and this can be a time-consuming process given the many other stories that are competing for space or airtime.

ADDITIONAL RESOURCES

For more information about writing like a journalist in a pyramidal fashion including an example of a famous news story see http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Inverted_pyramid

Oxfam GB November 2012 This guideline has been prepared by Oxfams Global Research Team and Oxfam GBs Policy and Practice Communications Team for use by staff, partners, and other development practitioners and researchers. It was written by John Magrath and edited with the help of Martin Walsh. The text may be used free of charge for the purposes of education and research, provided that the source is acknowledged in full. The copyright holder requests that all such use be registered with them for impact assessment purposes. For copying in any other circumstances, or for re-use in other publications, or for translation or adaptation, permission must be secured and a fee may be charged. E-mail publish@oxfam.org.uk Oxfam welcomes comments and feedback on its Research Guidelines. If you would would like to discuss any aspect of this document, please contact research@oxfam.org.uk. For further information on Oxfams research and publications, please visit www.oxfam.org.uk/policyandpractice The information in this publication is correct at the time of going to press. Published by Oxfam GB under ISBN 978-1-78077-223-3 in November 2012. Oxfam GB, Oxfam House, John Smith Drive, Cowley, Oxford, OX4 2JY, UK. Oxfam is a registered charity in England and Wales (no 202918) and Scotland (SC039042). Oxfam GB is a member of Oxfam International.

Você também pode gostar

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)No EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Nota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (98)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeNo EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (5794)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingNo EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (400)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureNo EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryNo EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (231)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceNo EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (895)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnNo EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (234)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItNo EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (838)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerNo EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (271)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaNo EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (266)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaNo EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (45)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersNo EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (345)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyNo EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (2259)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreNo EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)No EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Nota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (121)

- English NotesDocumento32 páginasEnglish NotesClair O.B100% (1)

- KERANGKA ACUAN KEGIATAN LOMBA ILMIAH DALAM BAHASA INGGRIS Dies Natalis 2024Documento10 páginasKERANGKA ACUAN KEGIATAN LOMBA ILMIAH DALAM BAHASA INGGRIS Dies Natalis 2024Putrinda Jingga SarastikaAinda não há avaliações

- Mage The Sorcerers CrusadeDocumento315 páginasMage The Sorcerers Crusadekramwalhalla100% (11)

- Reading and Writing Q1 - M1Documento14 páginasReading and Writing Q1 - M1ZOSIMO PIZON67% (3)

- ActivitiesDocumento2 páginasActivitiesMhelody VioAinda não há avaliações

- Spike Lee and Commentary On His WorkDocumento92 páginasSpike Lee and Commentary On His Workaliamri100% (1)

- Ielts Practice Test 2020Documento20 páginasIelts Practice Test 2020SELS IELTS78% (9)

- MYP Drama Subject Overview 2016 2017Documento11 páginasMYP Drama Subject Overview 2016 2017ricky fiascoAinda não há avaliações

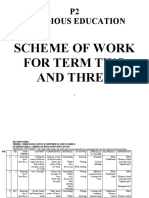

- P2 Religious Education: Scheme of Work For Term Two and ThreeDocumento11 páginasP2 Religious Education: Scheme of Work For Term Two and ThreeMonydit SantinoAinda não há avaliações

- In The Skin of A Lion EssayDocumento3 páginasIn The Skin of A Lion EssaylakedtAinda não há avaliações

- Teaching Young Learners English - From Theory To PracticeDocumento416 páginasTeaching Young Learners English - From Theory To PracticeCesar Pablo100% (3)

- Literatura LakototaDocumento48 páginasLiteratura LakototaFino UtzAinda não há avaliações

- Indigenous Storytelling UnitDocumento13 páginasIndigenous Storytelling Unitapi-535056577Ainda não há avaliações

- ImagineFX November 2015Documento116 páginasImagineFX November 2015Paula Nicodin100% (2)

- Film Genres: by John M. Grace, Film Worker and Instructor D.A.T.A. Charter High School Albuquerque, NMDocumento87 páginasFilm Genres: by John M. Grace, Film Worker and Instructor D.A.T.A. Charter High School Albuquerque, NMMdMehediHasanAinda não há avaliações

- Fences Reference GuideDocumento13 páginasFences Reference GuideFaith CalisuraAinda não há avaliações

- Design Thinking For Food - An Overview and Potential Application For Grains 2018Documento4 páginasDesign Thinking For Food - An Overview and Potential Application For Grains 2018CINTHIA SATURNINA AGUILAR CORRALESAinda não há avaliações

- Retelling Stories in OrganizationsDocumento22 páginasRetelling Stories in OrganizationsUdbodh BhandariAinda não há avaliações

- Ambassodor PDFDocumento46 páginasAmbassodor PDFPatsonAinda não há avaliações

- Soal Bahasa Inggris Kelas 9Documento4 páginasSoal Bahasa Inggris Kelas 9Putri MaharaniAinda não há avaliações

- Benjamin's Materialistic Theory of Experience. Richard WolinDocumento27 páginasBenjamin's Materialistic Theory of Experience. Richard Wolinmbascun1Ainda não há avaliações

- Beyond Narrative Coherence PDFDocumento205 páginasBeyond Narrative Coherence PDFoxana creangaAinda não há avaliações

- Classification of Character StrengthsDocumento2 páginasClassification of Character StrengthsSzabados SándorAinda não há avaliações

- Multilingual Education in Orissa Community, Culture and Curriculum - FinalDocumento18 páginasMultilingual Education in Orissa Community, Culture and Curriculum - FinalMahendra Kumar MishraAinda não há avaliações

- Narrative Effect LoopDocumento2 páginasNarrative Effect LoopRobert GreenbergAinda não há avaliações

- Beowulf Oral TraditionDocumento17 páginasBeowulf Oral Traditionapi-327692565Ainda não há avaliações

- SangkuriangDocumento1 páginaSangkuriangHerlinaputri PutriAinda não há avaliações

- Storytelling - Design Research TechniquesDocumento4 páginasStorytelling - Design Research TechniquesPaolo BartoliAinda não há avaliações

- Brain PickingsDocumento116 páginasBrain PickingsEric Henry100% (1)