Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

A Feminist Approach To Boatwright Women

Enviado por

Emilee RuhlandDescrição original:

Título original

Direitos autorais

Formatos disponíveis

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

A Feminist Approach To Boatwright Women

Enviado por

Emilee RuhlandDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

A Feminist Approach to Boatwright Women: Aunt Raylene and Mama as Mother Figures in Bastard Out of Carolina I wrapped my fingers

in Raylenes and watched the night close in around us (Allison 309). In Dorothy Allisons Bastard Out of Carolina, Bone is abused, and it is only her extended family that keeps her from ending up like her friend Shannon Pearl, who kills herself. The Boatwright women especially play a monumental role in Bones character development. Bone stays with three of her aunts in the course of the novel, and the rest of the Boatwright women make frequent appearances. At the beginning of the story Bone believes anything her Mama says. Although the beginning belongs to Mama, the very end belongs to Aunt Raylene. Allison invokes the concept of the definition of woman through the eyes of men with her focus on the Boatwright sisters. It is seen through a feminist lens that Mama and Aunt Raylene become opposites who affect Bone through their decisions. Whereas Mama does her best to conform to the societal and male definition of a woman, Aunt Raylene is thoroughly unconcerned about societal norms and becomes the ideal and only mother for Bone. Although Mamas marriage to Daddy Glen is supposed to be for the entire family, it becomes more important to Mama to achieve the status of a socially accepted and defined woman than whats best for the family. At the beginning of their marriage, Mama tells the girls this was a marriage for all of us (Allison 42). The marriage is to make them all safe, to provide all three girls with a man to fill the hole in their life and create stability. Mama embraces Glens logic of possessive paternity and celebrates the legal marriage that will produce them as a proper family (Harkins 120). The marriage is initially to help the family survive. However, in her effort to create a perfect family with the man she loves, Mama gets caught up in her attempts to be a proper woman for Glen, who she feels lost without. Virginia Woolf was the first to declare that

Ruhland, 2 the male defines female by their non-maleness, and we can see how Mama craves that definition in her relationship with Daddy Glen (Bressler 181). Courtney George explains, the Boatwright womenlike honky-tonk angelsoften let the men in their lives define them (140). Even when it is apparent that this relationship will hurt her child, Mama is too dependent on Glen, and thats why when Glen seemingly offers Anney an escape, she takes it, even at the cost of her own child (Bouson 109). Mama lets her adherence to the role of a socially proper, defined-by-man woman get in the way of her relationship with Bone. Aunt Raylene is different than other Boatwright women and does not concern herself with following the accepted and required norms of society. She lives her life differently from her sistersalone on the river where trash rises (180). She lets children run free, she can fix a car like a man, she is the best cook in the family, and she encourages Bone more than anyone else (George 140). This description gives Aunt Raylene a seemingly ambiguous gender role. Raylene cooks like a woman in this time period, but she fixes cars as a man would. In literature there are two typical images of womenthat of the angel in the house, and the madwoman in the attic (Bressler 186). While Mama strives for the angel image, Raylene rejects it and the madwoman idea, deciding instead to be ambiguous in societys terms. In spite of her image as an aunt who spoils and lets the children run around, Raylene gives Bone the advice she needs to hear and is there for her before, during and after her mother leaves her. Before Bone goes to her house for the first time, she says that Raylene let kids do pretty much anything they wanted (Allison 178). She lets the boys smoke in her yard and even curse. As Raylene becomes a bigger part of the story, though, the reader is introduced to her stern, motherly side. When Deedee doesnt want to go to her mothers funeral, Raylene slaps her and calmly tells her, youre going to her funeral the way she would want. If you dont, ten years

Ruhland, 3 from now youre gonna hate yourself for missing it, and I damn sure am not gonna let that go by (Allison 237). She isnt concerned about what Deedee thinks about her at that moment, or about letting her act like a child. Instead Raylene is concerned with what is the right thing to do, and she is intent on making Deedee understand that. This scene is one of the first where Raylene shows her motherly, forceful side. Then, Raylene sees Bones backside, where Daddy Glen belted her so hard it left bloody strips of skin that scabbed painfully. From that moment on, Raylene is determined to save Bone, and she is there for her throughout the rest of the hardships she faces. Bone recognizes this, and when she leaves the apartment her Mama rented, it is to Raylenes house that she walks. Bone says, Aunt Raylene didnt seem that surprised when Bone walks up her steps, and only briefly looks up from her plants to acknowledge her (Allison 256). Even now, Raylene understands what Bone wants; Bone wants her presence but no mention of what has happened. When she begins to talk to her, shes doing what Bone needs rather than wants. Raylene gives Bone that feeling of normalcy, the feeling that they can have a conversation thats not about pain and what Daddy Glen does. Raylene is not able to save Bone from the final assault of Daddy Glen, but she saves Bone from the terror that these assaults and abuse brought about. While Bone is dealing with Daddy Glen she begins to create stories, listen to gospel music, and becomes friends with Shannon Pearl. She is looking for something special, something magical, stories which can transform her and her world (King 134). Bone creates stories from the start of the book. Her first story is innocent and is a way to stop her sister from hitchhiking. As she becomes more upset and abused by Daddy Glen though, they become more violent and, also, freeing for a woman of her status. This reflects her attempts to create stories (read identities) that will provide her with what Allison describes as the hope of a remade life

Ruhland, 4 (King 124). As her stories get more violent, they become more hopeless, with Bone only being able to identify with the outsider, the outcast. It is during her stay with Raylene that Bone begins to understand that she can heal. That magic she was looking for is not found in gospel music, in the mean-hearted tales she shares with Shannon Pearl, in her violent sexual fantasies, or even in her reading (King 134). It is Raylene who offers her a chance at the magic. Her dreams and stories begin to change after she walks to Raylenes from the apartment. Her stories morph from morbid and hopeless. Instead, she began to imagine the highway that went northonly the stars guided me, and I was not sure where I would end (Allison 259). When she moves back with her Mama, Raylene still stays with her as a guiding mentor, teaching her the lessons that her Mama has failed to realize. To continue her motherly role, Raylene visits after Bone moves back and it is in one of these visits that Raylene offers Bone another lesson on her stories. Raylene teaches [Bone] how to create a different kind of story, one based on something more than hate (King 135). Bone tells Raylene that she hates the kids in the bus, who she says stare hatefully. They look at you the way you look at them, Raylene says clearly (Allison 262). Raylene is trying to make Bone understand that there are stories other than the horrible ones she imagines. She asks Bone to step in their shoes, imagine what they might go through. Even when Bone gives a rude response, and even mentions painful gossip, Raylene never deserts her. As Aunt Raylene begins to replace Mama as the mother of Bone, she begins to become more than just the opposite of Mamas attempt to the angel-figure. Instead, Aunt Raylene is what George describes as a honky tonk angel free of patriarchal constructionsRaylenes perceptions of love and tolerance are central to her worldview (141). She isnt just the madwoman in the attic. Raylene is there for Bone, offering Bone a place to live after her

Ruhland, 5 mother leaves her, and being there for her. While Bone is staying with Raylene, she decides never to live again in the same house with Daddy Glen (King 134). She gains confidence and although she is still assaulted by Glen, Rayleneis there to pick up the pieces (King 134). She refuses to leave Bones hospital room until she can leave, and she protects her against men like the Sheriff who, although they want to help her, are making Bone uncomfortable and scared (Allison 298). The Sheriff is kind, but not understanding of how to deal with a twelve-year-old child who has been through an abusive childhood. Right now she needs to feel safe and loved, not alone and terrified Raylene reprimands him (Allison 298). Raylene gives her the enduring love that Bone might not want, but that is what gives Bone the chance to heal and take advantage of the blank, unmarked, unstamped beginning of a new chapter in her life (Allison 309). Bastard Out of Carolina ends with Mama deserting Bone for Daddy Glen. It seems a gothic, miserable end to the story, but the audience needs to realize that Bones story isnt over. Bone is left with her Aunt Raylene, a woman who may not be her genetic mother but is nonetheless the real mother for Bone. Raylene doesnt allow societal conditions to cloud her judgment and unconditional love of Bone, nor does she let Bones behaviorwhich Raylene understands is the result of her abused childhoodget in the way of raising Bone in the best way possible. Bone is given the best chance she can to heal from her past and continue to grow from it, becoming a woman that Dorothy Allisonas well as the audiencewould be proud of.

Ruhland, 6

Works Cited Allison, Dorothy. Bastard out of Carolina. New York: Dutton, 1992. Print. Bouson, J. Brooks. "'You Nothin but Trash': White Trash Shame in Dorothy Allison's Bastard Out of Carolina." Southern Literary Journal 34.1 (2001): 101-123. EBSCO. Web. 15 Oct 2012. Bressler, Charles. "Feminism." Literary Criticism: An Introduction to Theory and Practice. 2. Upper Saddle River: Prentice Hall, 1999. 178-209. EBSCO. Web. 15 Oct. 2012. George, Courtney. ""It Wasn't God Who Made Honky-Tonk Angels": Musical Salvation in Dorothy Allison's "Bastard Out of Carolina"." Southern Literary Journal 41.2 (2009): 126-47. EBSCO. Web. 12 Oct 2012. Harkins, Gillian. "Surviving the Family Romance? Southern Realism and the Labor of Incest." Southern Literary Journal 40.1 (2007): 114-139. EBSCO. Web. 15 Oct 2012. King, Vincent. "Hopeful Grief: The Prospect of a Postmodernist Feminism in Allison's Bastard Out of Carolina." Southern Literary Journal 33.1 (2000): 122-141. EBSCO. Web. 15 Oct 2012.

Você também pode gostar

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeNo EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (5794)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreNo EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (1090)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItNo EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceNo EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (895)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersNo EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (344)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureNo EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (474)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)No EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Nota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (120)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerNo EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingNo EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (399)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyNo EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)No EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Nota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaNo EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryNo EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnNo EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (234)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaNo EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (45)

- BIOETHICSDocumento4 páginasBIOETHICSSherylou Kumo SurioAinda não há avaliações

- Auguste Comte - PPT PresentationDocumento61 páginasAuguste Comte - PPT Presentationmikeiancu20023934100% (8)

- 08 - Case Law-Unknown Case Law ListDocumento28 páginas08 - Case Law-Unknown Case Law ListNausheen100% (1)

- Management Decision Case: Restoration HardwaDocumento3 páginasManagement Decision Case: Restoration HardwaRishha Devi Ravindran100% (5)

- Letter of IntroductionDocumento2 páginasLetter of IntroductionEmilee RuhlandAinda não há avaliações

- Progress ReportDocumento2 páginasProgress ReportEmilee RuhlandAinda não há avaliações

- Final PaperDocumento13 páginasFinal PaperEmilee RuhlandAinda não há avaliações

- Emilee Ruhland: Relevant ExperienceDocumento2 páginasEmilee Ruhland: Relevant ExperienceEmilee RuhlandAinda não há avaliações

- Writing in The ClassroomDocumento9 páginasWriting in The ClassroomEmilee RuhlandAinda não há avaliações

- The Exploration of A DreamDocumento9 páginasThe Exploration of A DreamEmilee RuhlandAinda não há avaliações

- Monster in The ClosetDocumento7 páginasMonster in The ClosetEmilee RuhlandAinda não há avaliações

- ProposalDocumento4 páginasProposalEmilee RuhlandAinda não há avaliações

- Final PaperDocumento13 páginasFinal PaperEmilee RuhlandAinda não há avaliações

- Our American HeritageDocumento18 páginasOur American HeritageJeremiah Nayosan0% (1)

- "Land Enough in The World" - Locke's Golden Age and The Infinite Extension of "Use"Documento21 páginas"Land Enough in The World" - Locke's Golden Age and The Infinite Extension of "Use"resperadoAinda não há avaliações

- Marking Guide For MUNsDocumento2 páginasMarking Guide For MUNsNirav PandeyAinda não há avaliações

- Internship ReportDocumento44 páginasInternship ReportRAihan AhmedAinda não há avaliações

- Quotes For Essay and Ethics CompilationDocumento5 páginasQuotes For Essay and Ethics CompilationAnkit Kumar SinghAinda não há avaliações

- Strategic Management AnswerDocumento7 páginasStrategic Management AnswerJuna Majistad CrismundoAinda não há avaliações

- Professionals and Practitioners in Counselling: 1. Roles, Functions, and Competencies of CounselorsDocumento70 páginasProfessionals and Practitioners in Counselling: 1. Roles, Functions, and Competencies of CounselorsShyra PapaAinda não há avaliações

- The City Bride (1696) or The Merry Cuckold by Harris, JosephDocumento66 páginasThe City Bride (1696) or The Merry Cuckold by Harris, JosephGutenberg.org100% (2)

- 10ca Contract Manual 2005Documento4 páginas10ca Contract Manual 2005Kavi PrakashAinda não há avaliações

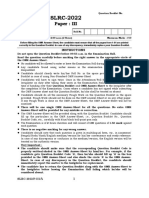

- SLRC InstPage Paper IIIDocumento5 páginasSLRC InstPage Paper IIIgoviAinda não há avaliações

- Moral Dilemmas in Health Care ServiceDocumento5 páginasMoral Dilemmas in Health Care ServiceYeonnie Kim100% (1)

- ISA UPANISHAD, Translated With Notes by Swami LokeswaranandaDocumento24 páginasISA UPANISHAD, Translated With Notes by Swami LokeswaranandaEstudante da Vedanta100% (4)

- Regulus Astrology, Physiognomy - History and SourcesDocumento85 páginasRegulus Astrology, Physiognomy - History and SourcesAntaresdeSuenios100% (3)

- Research ProposalDocumento8 páginasResearch ProposalZahida AfzalAinda não há avaliações

- The Seventh Level of Intelligence Is The Highest Level Which Is The Level of Infinite IntelligenceDocumento1 páginaThe Seventh Level of Intelligence Is The Highest Level Which Is The Level of Infinite IntelligenceAngela MiguelAinda não há avaliações

- 22ba093 - Souvick SahaDocumento12 páginas22ba093 - Souvick SahaSouvickAinda não há avaliações

- Elizabeth Stevens ResumeDocumento3 páginasElizabeth Stevens Resumeapi-296217953Ainda não há avaliações

- Customer Perception Towards E-Banking Services Provided by Commercial Banks of Kathmandu Valley QuestionnaireDocumento5 páginasCustomer Perception Towards E-Banking Services Provided by Commercial Banks of Kathmandu Valley Questionnaireshreya chapagainAinda não há avaliações

- Indian Contract Act 1972Documento37 páginasIndian Contract Act 1972Ashutosh Saraiya100% (2)

- Marathi 3218Documento11 páginasMarathi 3218Nuvishta RammaAinda não há avaliações

- University Institute of Legal Studies: Jurisprudence-Austin'S Analytical Positivism 21LCT114Documento15 páginasUniversity Institute of Legal Studies: Jurisprudence-Austin'S Analytical Positivism 21LCT114Harneet KaurAinda não há avaliações

- PolinationDocumento22 páginasPolinationBala SivaAinda não há avaliações

- Professional Cloud Architect Journey PDFDocumento1 páginaProfessional Cloud Architect Journey PDFPraphulla RayalaAinda não há avaliações

- Obaid Saeedi Oman Technology TransfeDocumento9 páginasObaid Saeedi Oman Technology TransfeYahya RowniAinda não há avaliações

- Brand Management Assignment 1 FINALDocumento4 páginasBrand Management Assignment 1 FINALbalakk06Ainda não há avaliações

- SweetPond Project Report-2Documento12 páginasSweetPond Project Report-2khanak bodraAinda não há avaliações