Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

High Quality Civic Education:: What Is It and Who Gets It?

Enviado por

gpnasdemsulselDescrição original:

Título original

Direitos autorais

Formatos disponíveis

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

High Quality Civic Education:: What Is It and Who Gets It?

Enviado por

gpnasdemsulselDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

S o c i a l E d u c a t i o n

34

Research and Practice

High Quality Civic Education:

What Is It and Who Gets It?

Joseph Kahne and Ellen Middaugh

Interviewer: What are your

feelings about government and

politics?

Boys voice: Its boring.

Interviewer: When you say its

boring, whats boring about it?

Boys Voice: The subject mat-

ter.

Girls Voice: Yes, very true.

Boys Voice: Its not just the

work. Its what the work is

about. We dont care about it.

Focus group of high school seniors in a

traditional government classroom

It is commonly understood that dem-

ocratic self-governance requires an

informed and educated citizenry and

that access to education is an important

support for the development of such citi-

zens. Civic education, however, which

explicitly teaches the knowledge, skills

and values believed necessary for demo-

cratic citizenship, currently holds a tenu-

ous position in American public schools.

It was common in the 1960s for students

to take multiple courses in civics cover-

ing not only the structure of American

government but also the role of citizens

and the issues they and the government

face. Students today, however, typically

take only one semester-long course on

American government.

1

These courses

tend to focus on factual knowledge of

American government (e.g. contents of

the Constitution and branches of govern-

ment) and give considerably less attention

to the role of common citizen.

2

What brought about this retreat from

civic curricula? Any change in educa-

tional practice is likely the result of a

number of influences. However, two

important challenges to civic education

seem particularly relevant for under-

standing why it is such a small part of

public schooling today and whether

greater attention to the subject is war-

ranted.

One challenge is the belief by some

that civics instruction is relatively less

important than, and takes time away

from, subjects such as math, science

and reading. Indeed, the now famous

1983 report A Nation at Risk identi-

fed increasing pressures on schools to

provide solutions to personal, social,

and political problems as a core threat

to providing quality education.

3

The

authors acknowledge the importance

of an educated citizenry for democracy,

but focus on the need to develop general

skills such as literacy, critical thinking,

and labor market skills rather than skills,

knowledge, and thinking specifc to civic

participation and deliberation. This posi-

tion has been increasingly evident in edu-

cational policy. Most notably, the No

Child Left Behind Act of 2002 requires

schools to conduct assessments in math,

reading/language arts, and science only.

The accountability measures tied to these

assessments suggest that little importance

is placed on civic outcomes. It is not sur-

prising, then, that civics courses have

fallen by the wayside. Indeed, a 2006

study by the Center on Education pol-

icy found that 71% of districts reported

Social Education 72(1), pg 3439

2008 National Council for the Social Studies

Research and Practice, established early in 2001, features educational research

that is directly relevant to the work of classroom teachers. In this, the 20th article

in the series, I invited Joseph Kahne and Ellen Middaugh to report on the current

status of high-quality civic education in the U.S.what defnes it and who gets it.

Walter C. Parker, Research and Practice Editor,

University of Washington, Seattle.

J a n u a r y / F E b r u a r y 2 0 0 8

35

cutting back time on other subjects to

make more space for reading and math

instruction.

4

Social studies was the part of

the curriculum that was most frequently

cited as the place where these reductions

occurred.

While recent analyses of national

tests of academic achievement suggest

that some important gains have been

made since 1990, these gains appear

primarily in the area of math and only

for younger students.

5

In spite of pres-

sures to focus on curricular areas of

math and reading, we see little or no

progress in reading achievement since

1990 and little to no improvement for

reading or math among high school stu-

dents.

6

Meanwhile, numerous studies

have found that levels of informed civic

engagement are lower than desirable, and

in many cases, are declining.

7

As a panel

of experts convened by the American

Political Science Association recently

found, Citizens participate in public

affairs less frequently, with less knowl-

edge, and enthusiasm, in fewer venues,

and less equitably than is healthy for a

vibrant democratic polity.

8

For example, voting rates of those

under age 25 in U.S. presidential elec-

tions have declined steadily from 52%

to 37% between 1972 (the frst election

when 18 year-olds were given the right

to vote in a presidential election) and

2000.

9

Similarly, youth interest in dis-

cussing political issues declined to their

lowest levels since historic highs in the

1960s.

10

Roughly 25% of young people

from 1960-1976 reported that they fol-

lowed public affairs most of the time,

but by 2000, that number had declined

to 5%.

11

Although young peoples vot-

ing rates increased somewhat in the

November 2004 elections in the United

States, youth voters remained roughly

the same proportion of the total elector-

ate.

12

Furthermore, it is unclear whether

this up-tick in turnout will be sustained,

and more importantly, whether it will be

accompanied by increases in students

knowledge and interest in following

politics. As important as voting may be,

informed and educated voting is more

important.

Given the overall low levels of youth

commitment to and capacity for political

participation, it is clear that many young

people are not having experiences in or

out of school that support their develop-

ment into informed and effective citizens.

With this in mind, we address the sec-

ond challenge to civic educationthe

question of whether civics classes can

be effective for encouraging the develop-

ment of youth civic commitments and

capacities.

Early evaluations of the impact of high

school government courses found little

relationship between exposure to such

curriculum and youth political orienta-

tions, casting considerable doubt on their

effectiveness.

13

These studies, however,

focused on U. S. government courses

and civics courses in general, with little

attention to differences in quality. Indeed,

Langton and Jennings note that in spite

of their fndings about the general effects

of government courses, there is reason

to believe that under special conditions,

exposure to government and politics

courses does have an impact at the sec-

ondary level.

14

Uncovering what these

special conditions might be and fguring

out how to make them more typical has

become the focus of some recent research

and related educational practice and

policy work.

The purpose of this article is to share a

model of high quality civic education and

the research base that supports it. Using

this model, we then examine the extent

to which high quality civic education is

available to students across a diverse set

of schools in the state of California.

A Model of High Quality Civic

Education

In response to doubts about whether civic

education can have a substantial impact

on youth civic and political engagement,

some scholars have focused their atten-

tion on understanding how youth who are

active and engaged became that way and,

in turn, how schools might incorporate that

knowledge to provide better quality civic

education.

15

Perhaps the most thorough

treatment of this issue is undertaken by

James Youniss and Miranda Yates, whose

work provides a conceptualization of the

factors that promote the development of a

civic identity.

16

Drawing on Erik Eriksons

Identity, Youth, and Crisis, Youniss and

Yates argue that a prime task of late adoles-

cence is the development of a social iden-

tity that embraces an orientation towards

civic and political participation.

17

As they

state, Gaining a sense of agency and feel-

ing responsible for addressing societys

problems are distinguishing elements that

mark mature social identity.

18

They also

identify three kinds of opportunities that

can spur such development: opportuni-

ties for agency and industry, for social

relatedness, and for the development of

political-moral understandings. Their

model was designed to help explain how

various kinds of service-learning experi-

ences can promote a sense of social respon-

sibility in youth.

In an earl ier st udy wit h Joel

Westheimer, we adapted this framework

from service learning specifcally to civic

education generally.

19

Our reasoning was

that a mature social identity that sup-

ports civic engagement can be fostered

by opportunities that develop students

sense of their civic and political capaci-

ties, connections, and commitments.

While the terminology is more specifc

to civic education, the framework is the

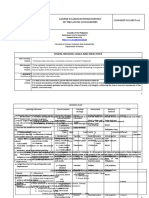

same. Our model (see Figure 1) assumes

that students broad commitment to civic

participation will be enhanced when

they develop the sense that they have

the capacity to be effective as civic actors,

when they feel connected to groups and

other individuals who share their com-

mitments and/or can facilitate their

involvement and effectiveness as civic

actors, and when they have formed par-

ticular and strong commitments with

respect to specifc social issues.

The model also provides a way to

understand how curricular experiences

can foster broad civic commitments by

developing students sense of their civic

capacities, connections, and commit-

ments to particular issues. For example,

opportunities to learn about ways to

improve the community might reason-

ably be expected to foster a sense of

civic capacity. Meeting civically-active

S o c i a l E d u c a t i o n

36

role models and participating in service

projects might be expected to foster a

sense of civic connection. And learn-

ing about social problems or discussing

current events might be expected to fos-

ter commitments to particular societal

issues. Moreover, some opportunities,

depending on how they are structured,

might be expected to foster more than one

of these intermediary outcomes.

Experiences that Foster Civic

and Political Commitments and

Capacities

Prior studies have found that the quantity

of civic education bears little relationship

to young peoples later civic and politi-

cal activity. Yet, when studies focus on

practices that align with the model of high

quality civic education just described,

the results are more promising. Indeed,

recent research has found a fairly broad

variety of school-based opportunities

(the curricular supports in our model)

that are related to increased levels of civic

and political commitments, capacities,

and activities amongst youth. A con-

sensus statement from leaders in the

feld identifed six promising practices

research has found to be related to higher

levels of students civic or political com-

mitment, knowledge, skills and activi-

ties. These include information about

the local, state, and national government;

opportunities to debate and discuss cur-

rent events and other issues that matter to

students; service-learning opportunities;

experiences with extra curricular activi-

ties; opportunities for youth decision

making; and engaging in simulations of

civic processes.

20

Other researchers have

identifed additional practices such as

open classroom environments and con-

troversial issue discussions.

21

Currently, much of the research is cor-

relational, leaving open the question of

whether these experiences lead to greater

civic commitments and capacities or are

sought out by students who are already

interested in civic and political engage-

ment. However, some recent studies that

used pre/post designs and control groups

have begun to address this concern. These

studies have focused on particular cur-

ricular initiatives such as service learn-

ing, examining upcoming elections, and

experience-based curriculum for high

school government courses.

22

In addition,

we recently completed a large-scale lon-

gitudinal study that, unlike prior large-

scale studies, examined multiple civic

learning opportunities associated with

best practice and controlled for students

prior civic commitments. We found that

meeting civic role models, learning about

problems in society, learning about ways

to improve ones community, having ser-

vice-learning experiences, being required

to keep up with politics and government,

being engaged in open classroom discus-

sions, and studying topics about which

the student cares, all promoted commit-

ments to civic participation among high

school students. And the magnitude of

this impact was substantial. We found

Curricular Supports for the Development of Civic and

Political Commitments to Working to Make the Society

Better

For example:

- Learnlng about ways to lmprove one's communlty

- worklng on communlty pro[ects

- Learnlng about current events

- Partlclpatlng ln after-school actlvltles

- Studylng lssues about whlch one cares

- Lxperlenclng an open classroom cllmate

- Meetlng and learnlng about clvlc role models

- Ltc.

Goal:

A soclal ldentlty that embraces clvlc and polltlcal

commltments to worklng to make soclety better.

Civic and Political Commitments

to worklng to make soclety better

Capacities for

informed civic and

political action

Connections to

those committed to

civic and political

engagement

Commitments to

specic issues

and ideals

Figure 1.

J a n u a r y / F E b r u a r y 2 0 0 8

37

that if schools could increase their pro-

vision of these opportunities, then they

could more than offset differences in

civic engagement caused by differences

in opportunities in students home envi-

ronments.

23

What Kinds of Experiences with

Civic Opportunities do High

School Students Typically Have?

Given the evidence that some school-

based opportunities foster adolescents

civic commitments and capacities at a

time in their lives when they are form-

ing their own civic and political identity,

it makes sense to examine the extent to

which high school students typically have

access to these kinds of opportunities.

To address this question, we surveyed a

sample of 2,366 California high school

students to fnd out how frequently they

experienced the kinds of opportunities

that supported the development of com-

mitted, informed, and effective citizens.

The fndings suggest that students access

to these opportunities is uneven. Some

opportunities are more common than

others, and some students are more likely

than others to be afforded them.

When we asked students how often

they had each of the civic opportunities

detailed in Figure 1, the most common

answer was, a little.

24

And sometimes,

for some students, these desired oppor-

tunities dont occur at all. For example,

when asked how much of a chance stu-

dents had to say how they think the

school should be run, 36% said not at

all. Thirty-six percent also reported

never having the opportunity to partici-

pate in simulations or role-plays during

high school. And 34% report never being

part of a service-learning project while in

high school. Clearly, one need not have

these experiences as part of every class,

but sizable numbers of students are not

getting these opportunities at all.

While the overall portrait suggests that

many students have little experience with

a number of the opportunities, there were

some bright spots. In particular, students

were more likely to report frequent expe-

riences with learning about how govern-

ment works (68%), discussing current

events (58%) and being in classrooms

where a wide range of student views were

discussed (68%).

Unequal Access to

Opportunities

It is inevitable that students will have

different opportunities with respect to

promoting civic development depending

on the teachers they happen to have for

particular subjects. It should not be the

case, however, that these opportunities

are distributed on the basis of character-

istics such as race or class, or academic

standing. Unfortunately, there is evidence

that these kinds of systemic inequalities

exist. Our study of high school seniors

in California revealed differences in

access to opportunities related to race

and ethnicityeven when we controlled

for students different academic perfor-

mance and future educational goals.

25

Specifically, even with other con-

trols in place, students who identifed

as African Americans were less likely

than others to report having civically-

oriented government courses, less likely

to report having discussions of current

events that were personally relevant,

less likely to report having voice in the

school or classroom, and were less likely

to report opportunities for role plays or

simulations.

26

Students who identifed

as Asian reported more participation in

after-school activities and more voice in

the school than others, but less open dis-

cussion in the classroom. Students who

identifed themselves as Latino reported

fewer opportunities for service than oth-

ers and fewer experiences with role plays

and simulations. Students identifying as

White were more likely than others to

report having civically-oriented govern-

ment courses and were more likely to

report having voice in the classroom. We

also found that high school seniors who

did not expect to take part in any form

of post-secondary education reported

significantly fewer opportunities to

develop civic and political capacities

and commitments than those with post-

secondary plans. Indeed, the quantity of

opportunities provided for students was

strongly related to the amount of post-

secondary education a student expected

to receive.

27

A large body of evidence demonstrates

that signifcant differences exist between

various groups of adults with respect to

their engagement and infuence in the

political system. When explaining these

differences, most researchers emphasize

factors such as an individuals income,

level of education, and race; they do

not consider the role that schools may

play in exacerbating that inequality by

providing fewer civic learning opportu-

nities to that same group of students.

28

Though the magnitude of such school

effects in relation to other factors is not

yet clear, it does appear that schools

may well increase rather than decrease

inequalities related to civic and political

participation.

Conclusion: Moving towards

High Quality Civic Education for

All Students

There are many indications that the level

of student civic and political commit-

ments and capacities is less than desir-

able for a democratic society and that, in

many cases, it is declining. There is also

considerable evidence that educators can

We also found that high school seniors who did not expect to take

part in any form of post-secondary education reported signifcantly

fewer opportunities to develop civic and political capacities

and commitments than those with post-secondary plans.

S o c i a l E d u c a t i o n

38

help by providing a particular set of civic

learning opportunities. When schools

provide the kinds of opportunities that

allow students to learn and practice a

variety of civic skills, learn about how

government works, see how others engage

civically and politically, and grapple with

their own roles as future citizens, then we

see increases in both students commit-

ment to and capacity for future participa-

tion. Indeed, the promise of these civic

learning opportunities makes clear the

signifcant cost of policies that crowd out

attention to the preparation of citizens

and therefore diminish attention to these

practices.

We believe these civic learning oppor-

tunities may be important later in life, but

are particularly important at the high

school level. Not only is high school

the last period when young people in

America are guaranteed access to free

education, and to civic education (when it

is included), but it is a time when many

are making important decisions about

their future and their relationship to the

world. Unfortunately, many students,

particularly those who are not planning

to seek further education and those

who are members of politically under-

represented racial and ethnic groups,

report few experiences with the kinds

of opportunities that have been found

to be most effective.

At the same time, however, we are

also aware that there is much more that

we still must learn. Not all findings

regarding the impact of civic learning

opportunities have been positive, and

there is reason to believe that the varied

quality of these opportunities can alter

their impact. For example, some stud-

ies that control for prior commitments

find significant positive effects only

for high quality service learning.

29

In addition, recent studies indicate that

varied civic learning opportunities may

impact young people of different races

and social classes in differing ways. For

example, our recent qualitative study

of high school students in different

social contexts in California suggests

that, while the majority of students in

our sample had little interest in poli-

tics, youth from high income, majority

white communities were more likely to

view political engagement as effective,

but less likely to view these activities

as necessary or important compared

to their counterparts from a primarily

working-class, Latino community.

30

These differences in perception are

likely to influence how students per-

ceive and make use of opportunities for

civic education provided by the schools.

Indeed, Rubin found that middle and

high school students from privileged,

homogeneous environments were more

likely to experience the ideals expressed

in civic texts as congruous with their

daily experiences than were urban youth

of color.

31

Further studies are needed

to better understand how prior experi-

ences with and assumptions about the

functioning of U.S. democracy infuence

students perceptions of and outcomes

related to civic education.

Moreover, not all who rally behind

the banner of democratic citizenship

value the same outcomes. Some empha-

size knowledge, while others place a

J a n u a r y / F E b r u a r y 2 0 0 8

39

premium on participation, on critical

analysis, on personal responsibility, on

tolerance, or other priorities. And, not

surprisingly, studies have found that

different practices, and the ways that

different practices are used, may pro-

mote different capacities and commit-

ments related to democratic citizenship.

32

Therefore, even though it is increasingly

clear that a range of best practices can

promote desired civic outcomes, we still

have much to learn about how the quality

of these practices along with the social

contexts in which they are implemented

infuence their impact. If our democracy

is to better fulfll its promise of enabling

all citizens to participate fully and as

equals, it is also clear that we must do

more to understand why schools often

fail to provide equal access to civic learn-

ing opportunities and how educators can

address this shortcoming.

Notes

1. R. Niemi and J. Smith, Enrollments in High School

Government Classes: Are We Short-Changing Both

Citizenship and Political Science Training? Political

Science and Politics 34, no. 2 (June 2001): 281-287.

2. P. Levine and M. Lopez, Themes Emphasized in

Social Studies and Civics Classes: New Evidence

(Center for Information and Research on Civic

Learning and Engagement, CIRCLE, 2004).

3. National Commission on Excellence in Education,

A Nation at Risk: The Imperative for Educational

Reform (Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing

Offce, 1983), 1.

4. Center on Education Policy, From the Capital to the

Classroom: Year Four of the No Child Left Behind

Act (Washington, D.C.: Center on Education Policy,

2006).

5. T. Loveless, The 2006 Brown Center Report on

American Education: How Well Are American

Students Learning? Vol. 2, no. 1 (Washington D.C.:

The Brookings Institution, October 2006).

6. Ibid., 9.

7. National Conference on Citizenship, Americas Civic

Health Index: Broken Engagement (A Report by the

National Conference on Citizenship in Association

with CIRCLE and Saguaro Seminar, 2006); R.

Putnam, Bowling Alone: The Collapse and Revival

of American Community (New York: Simon &

Schuster, 2000).

8. S. Macedo et al., Democracy at Risk: How Political

Choices Undermine Citizen Participation, and What

We Can Do About It (Washington, D.C.: Brookings

Institution, 2005).

9. P. Levine and M.H. Lopez, Youth Voter Turnout Has

Declined, By Any Measure (Washington, D.C.: Center

for Information and Research on Civic Learning and

Engagement, 2002).

10. L. J. Sax, Citizenship Development and the American

College Student, in Civic Responsibility and Higher

Education, ed. T. Ehrlich. (Phoenix, Ariz.: Oryx Press,

2000), 3-18.

11. C. Gibson and P. Levine, The Civic Mission of Schools

(New York and Washington, D.C.: The Carnegie

Corporation of New York and the Center for

Information and Research on Civic Learning and

Engagement, 2003).

12. See P. Levine and M. Lopez, Themes Emphasized in

Social Studies and Civics Classes: New Evidence.

(Washington, D.C.: Center for Information and

Research on Civic Learning and Engagement, 2004);

In response to these signs of declining interest, some

observers (and, in particular, youth from this gen-

eration) have argued that young people are participat-

ing in new non-traditional ways (S. Long, The New

Student Politics: The Wingspread Statement on

Student Civic Engagement. Providence, R.I.: The

Campus Compact, 2002). In addition to citing

increasing rates of volunteerism, proponents of this

view argue that youth participation is often informal

and grass-roots, and that youth acquire information

through alternative means such as the Internet. While

forms of civic and political engagement will vary by

generation, a systematic qualitative study of young

people that investigated this contention did not fnd

evidence to support it (M.W. Andolina, K. Jenkins,

S. Keeter, and C. Zukin, Searching for the Meaning

of Youth Civic Engagement: Notes From The Field,

Applied Developmental Science 6, no. 4 (2002):

189-195). Clearly, more work in the area of new forms

of civic participation is needed.

13. K. Langton and M.K. Jennings, Political Socialization

and the High School Civic Curriculum in the United

States, American Political Science Review 62 (1968):

862-67.

14. Ibid., 866.

15. The terms civic and political have been differ-

entiated in varied ways. Sherrod, Flanagan, and

Youniss, in Editors Note, Applied Developmental

Science 6, no. 4 (2002), 173-174, describe political

as referring to affairs of the state or the business of

government and civic as referring to membership

in a polity or community.

16. J. Youniss and M. Yates, Community Service and

Social Responsibility in Youth (Chicago, Ill.:

University of Chicago Press, 1997).

17. Erik H. Erikson, Identity: Youth and Crisis (New

York: W.W. Norton & Co., 1968).

18. Youniss and Yates, 36.

19. J. Kahne and J. Westheimer, Teaching Democracy:

What Schools Need To Do, Phi Delta Kappan 85,

no. 1 (2003), 34-40, 557-66.

20. See Gibson and Levine, 2003.

21. J. Torney-Purta, The Schools Role in Developing

Civic Engagement: A Study of Adolescents in Twenty-

Eight Countries, Applied Developmental Science

6 (2002): 203-212; D. Hess, Discussing Controversial

Public Issues in Secondary Social Studies Classrooms:

Learning from Skilled Teachers (University of

Washington Ph.D. Dissertation, 1998); Hess, How

Students Experience and Learn from the Discussion

of Controversial Public Issues in Secondary Social

Studies, Journal of Curriculum and Supervision 17,

no. 4 (2002): 283-314.

22. E.C. Metz and J. Youniss, Longitudinal Gains in

Civic Development through School-Based Required

Service, Political Psychology 26, no. 3 (2005):

413-438; M. McDevitt and S. Kiousis, Education

for Deliberative Democracy: The Long-Term

Infuence of Kids Voting (Working Paper #22,

Center for Information and Research on Civic

Engagement: University of Maryland, 2004); J.

Kahne, B. Chi, and E. Middaugh, Building Social

Capital for Civic and Political Engagement: The

Potential of High School Civics Courses, Canadian

Journal of Education 29, no. 2 (2006) 387-409.

23. J. Kahne and S. Sporte, Developing Citizens: The

Impact of Civic Learning Opportunities on Students

Commitment to Civic Participation. (Under review.

For working paper see: www.civicsurvey.org/

Democratic_Education_Reports_%26_Publications_.

html)

24. This fnding is consistent with the recent multi-nation

study by the International Association for the

Evaluation of Educational Achievement (IEA) which

found that 90% of U.S. students said that they most

commonly spent time reading textbooks and doing

worksheets (Baldi, S., M. Perie, D. Skidmore, E.

Greenberg, and C. Hahn, What Democracy Means

to Ninth Graders: U.S. Results from the International

IEA Civic Education Study [Washington, D.C.: U.S.

Department of Education, National Center for

Education Statistics, 2001]).

25. J. Kahne and E. Middaugh, Democracy for Some:

The Civic Opportunity Gap in High School (Under

review. For working paper see: www.civicsurvey.org/

Democratic_Education_Reports_%26_Publications_.

html)

26. For example, government courses where teachers

emphasize the importance of individual citizens stay-

ing informed and acting on issues that are relevant to

them.

27. Kahne and Middaugh, 2005.

28. See N.H. Nie, J. Junn, and K. Stehlik-Barry, Education

and Democratic Citizenship in America (Chicago:

University of Chicago Press, 1996); S. Verba, K.L.

Schlozman, and H.E. Brady, Voice and Equality:

Civic Volunteerism in American Politics (Cambridge,

Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1995); S.K.

Ramakrishnan and M. Baldassare, Ties that Bind:

Changing Demographics and Civic Engagement in

California (San Francisco: Public Policy Institute of

California, 2004).

29. See S. Billig, S. Root, and D. Jesse, The Impact of

Participation in Service Learning on High School

Students Civic Engagement, CIRCLE Working

Paper 33 (Washington, D.C.: Center for Information

and Research on Civic Learning and Engagement,

2005); A. Melchior, Final Report: National

Evaluation of Learn and Serve America and

Community-based Programs (Center for Human

Resources, Brandeis University: 1998).

30. E. Middaugh and J. Kahne, Civic Development in

Context: The Infuence of Local Contexts on High

School Students Beliefs about Civic Engagement in

Educating Citizens for Troubled Times: Qualitative

Studies of Current Efforts, eds. J. Bixby and J. Pace

(In Press, Albany: SUNY Press).

31. B. Rubin, Theres Still Not Justice: Youth Civic

Identity Development Amid Distinct School and

Community Contexts, Teachers College Record 109,

no. 7 (2007), www.tcrecord.org ID # 127771, accessed

on 10/16/2006.

32. J. Westheimer and J. Kahne, What Kind of Citizen?

The Politics of Educating for Democracy, American

Educational Research Journal 41, no. 2. (Summer

2004): 237-269; J. Torney-Purta and W.K.

Richardson, Trust in Government and Civic

Engagement among Adolescents in Australia, England,

Greece, Norway and the United States (Paper pre-

sented at the annual meeting of the American Political

Science Association, Boston, Mass., 2002).

Joseph Kahne is Abbie Valley Professor of Edu-

cation and dean of the School of Education at

Mills College in Oakland, California. The authors

research is accessible at www.civicsurvey.org.

Ellen Middaugh is a doctoral student in

Human Development and Education at the Uni-

versity of California at Berkeley.

Você também pode gostar

- Westheimer Teaching DemocracyDocumento17 páginasWestheimer Teaching DemocracyElize FontesAinda não há avaliações

- Public Engagement for Public Education: Joining Forces to Revitalize Democracy and Equalize SchoolsNo EverandPublic Engagement for Public Education: Joining Forces to Revitalize Democracy and Equalize SchoolsAinda não há avaliações

- Teaching Democracy:: What Schools Need To DoDocumento19 páginasTeaching Democracy:: What Schools Need To DoLTTuangAinda não há avaliações

- Deliberation & the Work of Higher Education: Innovations for the Classroom, the Campus, and the CommunityNo EverandDeliberation & the Work of Higher Education: Innovations for the Classroom, the Campus, and the CommunityNota: 5 de 5 estrelas5/5 (1)

- Civic Learning Opportunities and Civic CommitmentsDocumento58 páginasCivic Learning Opportunities and Civic CommitmentsVladankaAinda não há avaliações

- Teaching DemocracyDocumento20 páginasTeaching DemocracyDani ZsigovicsAinda não há avaliações

- Improving Schools through Community Engagement: A Practical Guide for EducatorsNo EverandImproving Schools through Community Engagement: A Practical Guide for EducatorsAinda não há avaliações

- BAB 3 KewarganegaraanDocumento16 páginasBAB 3 KewarganegaraanLitaNursabaAinda não há avaliações

- (A) Civic KnowledgeDocumento9 páginas(A) Civic KnowledgepodderAinda não há avaliações

- Why Civic Engagement Should Be Implemented in The Education System - EditedDocumento9 páginasWhy Civic Engagement Should Be Implemented in The Education System - EditedCandy OpiyoAinda não há avaliações

- "To Serve a Larger Purpose": Engagement for Democracy and the Transformation of Higher EducationNo Everand"To Serve a Larger Purpose": Engagement for Democracy and the Transformation of Higher EducationAinda não há avaliações

- The Future of Democracy: Developing the Next Generation of American CitizensNo EverandThe Future of Democracy: Developing the Next Generation of American CitizensNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (1)

- Guidelines For Citizenship Education inDocumento53 páginasGuidelines For Citizenship Education inPaula Josefa Neira MagliocchettiAinda não há avaliações

- The Public School Advantage: Why Public Schools Outperform Private SchoolsNo EverandThe Public School Advantage: Why Public Schools Outperform Private SchoolsNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (3)

- "The Job of A Citizen Is To Keep His Mouth Open"-: Ganter GrassDocumento3 páginas"The Job of A Citizen Is To Keep His Mouth Open"-: Ganter GrassMarcelo FrancoAinda não há avaliações

- Speaking of Politics: Preparing College Students for Democratic Citizenship through Deliberative DialogueNo EverandSpeaking of Politics: Preparing College Students for Democratic Citizenship through Deliberative DialogueAinda não há avaliações

- A Sample Qualitative StudyDocumento29 páginasA Sample Qualitative Studybluebell08Ainda não há avaliações

- Improving Civic Education in SchoolsDocumento3 páginasImproving Civic Education in SchoolsAleksandar PečenkovićAinda não há avaliações

- Between Movement and Establishment: Organizations Advocating for YouthNo EverandBetween Movement and Establishment: Organizations Advocating for YouthAinda não há avaliações

- Flunking Democracy: Schools, Courts, and Civic ParticipationNo EverandFlunking Democracy: Schools, Courts, and Civic ParticipationAinda não há avaliações

- Social Constructivism On The Culture of Senior High School Humss Students Towards Strengthening Voter'S EducationDocumento63 páginasSocial Constructivism On The Culture of Senior High School Humss Students Towards Strengthening Voter'S EducationguerrerosheenamaeAinda não há avaliações

- Literature Review On Citizenship EducationDocumento6 páginasLiterature Review On Citizenship Educationixevojrif100% (1)

- The Role of Assessment in Educating Democratic CitizensDocumento4 páginasThe Role of Assessment in Educating Democratic CitizensOlga Grijalva MartínezAinda não há avaliações

- Campus Politics Student Societies and SoDocumento20 páginasCampus Politics Student Societies and SoOluwatosin AdeeyoAinda não há avaliações

- Our Schools and Education: the War Zone in America: Truth Versus IdeologyNo EverandOur Schools and Education: the War Zone in America: Truth Versus IdeologyAinda não há avaliações

- John Dewey and the Decline of American EducationNo EverandJohn Dewey and the Decline of American EducationNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (3)

- Unprofitable Schooling: Examining the Causes of, and Fixes for, America's Broken Ivory TowerNo EverandUnprofitable Schooling: Examining the Causes of, and Fixes for, America's Broken Ivory TowerAinda não há avaliações

- Wrecked: Deinstitutionalization and Partial Defenses in State Higher Education PolicyNo EverandWrecked: Deinstitutionalization and Partial Defenses in State Higher Education PolicyAinda não há avaliações

- PA Times ArticleDocumento3 páginasPA Times ArticleSheri BaxterAinda não há avaliações

- Campus Politics, Student Societies and Social MediaDocumento20 páginasCampus Politics, Student Societies and Social MediaMurad KhanAinda não há avaliações

- Inequality in Key Skills of City Youth: An International ComparisonNo EverandInequality in Key Skills of City Youth: An International ComparisonStephen LambAinda não há avaliações

- The Future of School Integration: Socioeconomic Diversity as an Education Reform StrategyNo EverandThe Future of School Integration: Socioeconomic Diversity as an Education Reform StrategyAinda não há avaliações

- Civic Education Research PaperDocumento7 páginasCivic Education Research Paperfyh0kihiwef2100% (1)

- Lazickas N Scfemidterm Opt1Documento8 páginasLazickas N Scfemidterm Opt1api-303087146Ainda não há avaliações

- Racism in American Public Life: A Call to ActionNo EverandRacism in American Public Life: A Call to ActionAinda não há avaliações

- PCSReview2022 Essay Alcazaren1Documento19 páginasPCSReview2022 Essay Alcazaren1chocolate cupcakeAinda não há avaliações

- Troublemaker: A Personal History of School Reform since SputnikNo EverandTroublemaker: A Personal History of School Reform since SputnikNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (1)

- Part IV-Content Specific InstructionDocumento45 páginasPart IV-Content Specific InstructionFarah Zein EddinAinda não há avaliações

- Development StudiesDocumento102 páginasDevelopment StudiesJoy NapierAinda não há avaliações

- Creating Citizens: Liberal Arts, Civic Engagement, and the Land-Grant TraditionNo EverandCreating Citizens: Liberal Arts, Civic Engagement, and the Land-Grant TraditionBrigitta R. BrunnerAinda não há avaliações

- School Choice Myths: Setting the Record Straight on Education FreedomNo EverandSchool Choice Myths: Setting the Record Straight on Education FreedomAinda não há avaliações

- The Schooled Society: The Educational Transformation of Global CultureNo EverandThe Schooled Society: The Educational Transformation of Global CultureNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (1)

- Civic Education (Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy)Documento23 páginasCivic Education (Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy)4ieenereAinda não há avaliações

- Nelsen-Research Statement (7:15:19)Documento11 páginasNelsen-Research Statement (7:15:19)Matthew NelsenAinda não há avaliações

- Ensuring a Better Future: Why Social Studies MattersNo EverandEnsuring a Better Future: Why Social Studies MattersAinda não há avaliações

- Personal Reflection On Social Studies EducationDocumento6 páginasPersonal Reflection On Social Studies EducationKraigPeterson33% (3)

- Nelsen-Research StatementDocumento11 páginasNelsen-Research StatementMatthew NelsenAinda não há avaliações

- Higher Education for the Public Good: Emerging Voices from a National MovementNo EverandHigher Education for the Public Good: Emerging Voices from a National MovementAinda não há avaliações

- Social Studies PaperDocumento6 páginasSocial Studies Paperapi-623772170Ainda não há avaliações

- Educating the "GoodDocumento9 páginasEducating the "GoodEugene WongAinda não há avaliações

- The Problem with Rules: Essays on the Meaning and Value of Liberal EducationNo EverandThe Problem with Rules: Essays on the Meaning and Value of Liberal EducationNota: 1 de 5 estrelas1/5 (1)

- Racial Discrimination and Private Education: A Legal AnalysisNo EverandRacial Discrimination and Private Education: A Legal AnalysisAinda não há avaliações

- Civic Education Project 1Documento8 páginasCivic Education Project 1Makayla BlattenbergerAinda não há avaliações

- Hilly Gus PBDocumento23 páginasHilly Gus PBLjubica NovovićAinda não há avaliações

- An Age of Accountability: How Standardized Testing Came to Dominate American Schools and Compromise EducationNo EverandAn Age of Accountability: How Standardized Testing Came to Dominate American Schools and Compromise EducationAinda não há avaliações

- Weinberg, J. - Aprendiendo-Para-La-Democracia-La-Poltica-Y-La-Prctica-De-La-Educacin-Para-La-Ciudadana - Artculo - Acceso-Abierto - 2018Documento20 páginasWeinberg, J. - Aprendiendo-Para-La-Democracia-La-Poltica-Y-La-Prctica-De-La-Educacin-Para-La-Ciudadana - Artculo - Acceso-Abierto - 2018KhaligrafiasAinda não há avaliações

- The Stragtegic Co-Optation of Women's Rights-Discourse in The War On TerrorDocumento6 páginasThe Stragtegic Co-Optation of Women's Rights-Discourse in The War On TerrorgpnasdemsulselAinda não há avaliações

- MPS' Expenditure A ND General Election Campaigns: Do Incumbents Benefit From Contacting Their Constituents?Documento13 páginasMPS' Expenditure A ND General Election Campaigns: Do Incumbents Benefit From Contacting Their Constituents?gpnasdemsulselAinda não há avaliações

- Williams Trammell 2005 Proof Candidate Campaign e Mail Messages in The 2004 Presidential ElectionDocumento15 páginasWilliams Trammell 2005 Proof Candidate Campaign e Mail Messages in The 2004 Presidential ElectiongpnasdemsulselAinda não há avaliações

- Negative Advertising and Voter ChoiceDocumento33 páginasNegative Advertising and Voter ChoicegpnasdemsulselAinda não há avaliações

- 10 Myths EnglishDocumento3 páginas10 Myths EnglishgpnasdemsulselAinda não há avaliações

- Professional Is at I On of WhatDocumento7 páginasProfessional Is at I On of WhatgpnasdemsulselAinda não há avaliações

- Political Parties As Campaign OrganizationsDocumento35 páginasPolitical Parties As Campaign OrganizationsVinicius Do ValleAinda não há avaliações

- YouTube YesWeCan2008 Draft3Documento18 páginasYouTube YesWeCan2008 Draft3gpnasdemsulselAinda não há avaliações

- BrewerDocumento13 páginasBrewergpnasdemsulselAinda não há avaliações

- Cover SheetDocumento18 páginasCover SheetgpnasdemsulselAinda não há avaliações

- PRIVATE ETHICS AND PUBLIC POLICYDocumento13 páginasPRIVATE ETHICS AND PUBLIC POLICYgpnasdemsulselAinda não há avaliações

- PRIVATE ETHICS AND PUBLIC POLICYDocumento13 páginasPRIVATE ETHICS AND PUBLIC POLICYgpnasdemsulselAinda não há avaliações

- Xiaoxia and Brewer - Political Comedy Shows and Public Participation in PoliticsDocumento10 páginasXiaoxia and Brewer - Political Comedy Shows and Public Participation in PoliticsgpnasdemsulselAinda não há avaliações

- 63104984Documento19 páginas63104984gpnasdemsulselAinda não há avaliações

- Lilleker-Vedel 2013Documento38 páginasLilleker-Vedel 2013gpnasdemsulselAinda não há avaliações

- 63104984Documento19 páginas63104984gpnasdemsulselAinda não há avaliações

- Cover SheetDocumento18 páginasCover SheetgpnasdemsulselAinda não há avaliações

- Meetup, Blogs, and Online Involvement U.S. Senate Campaign Websites of 2004 PDFDocumento14 páginasMeetup, Blogs, and Online Involvement U.S. Senate Campaign Websites of 2004 PDFfadligmailAinda não há avaliações

- Campaigning in The Twenty-First Century: Dennis W. Johnson George Washington University Washington, D.CDocumento19 páginasCampaigning in The Twenty-First Century: Dennis W. Johnson George Washington University Washington, D.CgpnasdemsulselAinda não há avaliações

- Depaul University, Chicago: Political MarketingDocumento10 páginasDepaul University, Chicago: Political MarketingSabin PandeleaAinda não há avaliações

- Depaul University, Chicago: Political MarketingDocumento10 páginasDepaul University, Chicago: Political MarketingSabin PandeleaAinda não há avaliações

- 171Documento15 páginas171gpnasdemsulselAinda não há avaliações

- In Genta 847Documento14 páginasIn Genta 847gpnasdemsulselAinda não há avaliações

- 1-20040300521Documento7 páginas1-20040300521gpnasdemsulselAinda não há avaliações

- Meetup, Blogs, and Online Involvement U.S. Senate Campaign Websites of 2004 PDFDocumento14 páginasMeetup, Blogs, and Online Involvement U.S. Senate Campaign Websites of 2004 PDFfadligmailAinda não há avaliações

- Schneider Foot Webasobject 20030826Documento10 páginasSchneider Foot Webasobject 20030826gpnasdemsulselAinda não há avaliações

- Jankowski Et Al 2005 IpDocumento13 páginasJankowski Et Al 2005 IpgpnasdemsulselAinda não há avaliações

- Nisah Balsara Book ReviewDocumento5 páginasNisah Balsara Book ReviewgpnasdemsulselAinda não há avaliações

- 10 Bankole Et Al PDFDocumento9 páginas10 Bankole Et Al PDFgpnasdemsulselAinda não há avaliações

- Five Things to Know About Technological ChangeDocumento5 páginasFive Things to Know About Technological ChangegpnasdemsulselAinda não há avaliações

- Literature and Caste AssignmentDocumento4 páginasLiterature and Caste AssignmentAtirek SarkarAinda não há avaliações

- Guidelines of Seminar PreparationDocumento9 páginasGuidelines of Seminar Preparationanif azhariAinda não há avaliações

- Writing Correction SymbolsDocumento1 páginaWriting Correction SymbolsLuis Manuel JiménezAinda não há avaliações

- Samantha Jane Dunnigan: ProfileDocumento1 páginaSamantha Jane Dunnigan: Profileapi-486599732Ainda não há avaliações

- Trainers MethodologyDocumento3 páginasTrainers MethodologyPamela LogronioAinda não há avaliações

- IGS Term Dates 201819Documento1 páginaIGS Term Dates 201819Andrew HewittAinda não há avaliações

- Philippine Literature GenresDocumento10 páginasPhilippine Literature GenresWynceer Jay MarbellaAinda não há avaliações

- Effective Interventions For English Language Learners K-5Documento28 páginasEffective Interventions For English Language Learners K-5Jaycus Quinto100% (1)

- LTS-INTRODUCTIONDocumento34 páginasLTS-INTRODUCTIONAmir FabroAinda não há avaliações

- Ba History Hons & Ba Prog History-3rd SemDocumento73 páginasBa History Hons & Ba Prog History-3rd SemBasundhara ThakurAinda não há avaliações

- El Narrador en La Ciudad Dentro de La Temática de Los Cuentos deDocumento163 páginasEl Narrador en La Ciudad Dentro de La Temática de Los Cuentos deSimone Schiavinato100% (1)

- Phenomenology of The Cultural DisciplinesDocumento344 páginasPhenomenology of The Cultural DisciplinesJuan Camilo SotoAinda não há avaliações

- RRB NTPC Tier-2 Exam Paper Held On 19-01-2017 Shift-3Documento22 páginasRRB NTPC Tier-2 Exam Paper Held On 19-01-2017 Shift-3Abhishek BawaAinda não há avaliações

- Structured Learning Episode Competency: Hazard - A Dangerous Phenomenon, Substance, Human ActivityDocumento3 páginasStructured Learning Episode Competency: Hazard - A Dangerous Phenomenon, Substance, Human ActivityRachelle Dulce Mojica-NazarenoAinda não há avaliações

- Geometric Sequences Scavenger Hunt SIMDocumento16 páginasGeometric Sequences Scavenger Hunt SIMAlyssa Marie RoblesAinda não há avaliações

- Understanding the Causes and Risk Factors of Child DefilementDocumento6 páginasUnderstanding the Causes and Risk Factors of Child Defilementcrutagonya391Ainda não há avaliações

- English Lesson Plan - Irregular Plurals NovDocumento4 páginasEnglish Lesson Plan - Irregular Plurals Novapi-534505202Ainda não há avaliações

- l2 Teaching Methods and ApproachesDocumento22 páginasl2 Teaching Methods and ApproachesCarlos Fernández PrietoAinda não há avaliações

- Protective Factors SurveyDocumento4 páginasProtective Factors SurveydcdiehlAinda não há avaliações

- Cot Lesson PlanDocumento2 páginasCot Lesson PlanBlessel Jane D. BaronAinda não há avaliações

- The Last Lesson by Alphonse DaudetDocumento11 páginasThe Last Lesson by Alphonse DaudetalishaAinda não há avaliações

- Literature ReviewDocumento10 páginasLiterature Reviewapi-25443429386% (7)

- Syllabus Hist. 107 StudentDocumento6 páginasSyllabus Hist. 107 StudentloidaAinda não há avaliações

- Note: "Sign" Means Word + Concept Wedded Together.Documento2 páginasNote: "Sign" Means Word + Concept Wedded Together.Oscar HuachoArroyoAinda não há avaliações

- 2023 Tantra Magic and Vernacular ReligioDocumento24 páginas2023 Tantra Magic and Vernacular ReligioClaudia Varela ÁlvarezAinda não há avaliações

- Ableism KDocumento25 páginasAbleism Kalbert cardenasAinda não há avaliações

- 3-Methods of PhilosophyDocumento9 páginas3-Methods of PhilosophyGene Leonard FloresAinda não há avaliações

- Critical Book Review of "The Storm BoyDocumento10 páginasCritical Book Review of "The Storm BoyGomgom SitungkirAinda não há avaliações

- How Big Is The Problem FreeDocumento6 páginasHow Big Is The Problem FreeRoxana GogiuAinda não há avaliações

- Reviewer in Ucsp For Nat 2022-2023 ReferenceDocumento8 páginasReviewer in Ucsp For Nat 2022-2023 ReferencesabedoriarenaAinda não há avaliações