Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

Murderers I Have Known

Enviado por

Robin KirkTítulo original

Direitos autorais

Formatos disponíveis

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Murderers I Have Known

Enviado por

Robin KirkDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

MURDERERS I HAVE KNOWN Copyright Glamour Magazine, November 2005 Robin Kirk immerses herself in the world of men

who killnot to punish them, but to save them. Here, Glamours third annual essay contest winner tells why she tries, and what it costs her. Is that dog chained? It was winter in North Carolina. I was standing outside a trailer sunk in weeds. Rain had turned the driveway into a muddy ditch, which coursed into the muddy creek that was the road. A pit bull striped like a tiger glared at me, a rusted Chevy Impala the only thing between us. The woman watching me from her trailer next door shrugged in answer to my question. I was looking for the friend of a man charged with three shooting deaths in a trailer just like the one the pit bull was defending. Stripes, I decided to call him. He growled and took a step forward, and I heard the comforting rattle of a chain. Last year I started working as an investigator in capital punishment cases. My job is to find personal information that might convince juries not to impose the death penalty on defendants who have been charged with first-degree murder; I also help defendants who have been sentenced to death and are appealing, hoping for a new trial. I conduct interviews with the families of accused murderers, their teachers, their doctors, their friends, looking for any evidence of mental retardation or early abuse, among other things. I decipher 30-year-old notes made by psychiatrists about a mothers mental illness. I parse obituaries for clues to an overdose or alcoholism within a defendants family. Lawyers can use such personal details to show a jury how a defendants mental state or past may have impaired his ability to understand the consequences of a violent act, a necessary component of a first-degree conviction. At the very least, evidence of severe abuse can help move a jury to mercy. Since I took this job, my list of things Ive done for the first time in my life has grown. Once, I called a man to tell him about a son he never knew he had. After he absorbed this, I told him that his son was 35 years old and on death row. That is some news for a Tuesday morning. I told him he could help his son by talking to his sons lawyers. The man declined, then hung up. In another case, I worked with lawyers defending a young man from a Latin American country. Victor (not his real name) was charged with killing a prostitute. I speak Spanish and translated for his attorneys. Victor was so thrilled to talk with someone in his own language that his life story came out like hail on a tin roof. The two lawyers and I sat knee to knee in the sweltering visitors booth where glass separated us from Victor. He spoke in excruciating detail. My violence verbs, I realized, needed updating. As I

struggled to distinguish between knife and dagger, slap and punch, the lawyers grew wide-eyed. Tell him he faces a possible death sentence, one told me. Inadvertently, I laughed. You mean he doesnt know? The lawyer frowned, dismayed at my reaction. There is no death penalty in most of Latin Americaor much of the rest of the worldbut it had never occurred to me that I would have to relay this particular bit of news. It hadnt occurred to Victor, either. I told him that if his case went to trial, he could be sentenced to death. To defend him, I continued, we needed to ask him about his past. After a pause, he said, May I ask a question? Por supuesto. Of course. Can you ask them when I can go home? He hadnt comprehended the threat of death at all. Since that day, Victor has written me several letters from jail, where he is being held pending trial. He decorates them with elaborate pencil drawings of a grinning, winged heart wearing a halo, pictures like the kind a high schooler doodles on his spiral notebook. As my husband noted, the heart looks like a gang tattoo. But the drawings are the only gift Victor is capable of giving to say thank you for my visits. Jails are stinking, dirty and incredibly loud places. Once, I interviewed a clients cousin while the cousin was incarcerated for a minor crime. I wanted to find out what he remembered about my client when they were boys. While answering my questions quite calmly, the cousin started masturbating under his Popsicle-orange jumpsuit. It took me a minute to understand what was happening, especially because the cousin was also cheerily greeting other inmates with his free hand. Once I got over my initial shock, it turned out to be a useful interview. On the same case, my clients sister agreed to talk about her brothers early involvement with drugs. As we settled in her living room for the interview, her children ate quietly in the kitchen. Their awards for academic and sports accomplishments decorated the walls. On the porch, however, their father sold crack. To get the most out of the interview, I felt I had to ignore this and did. But as a mother myself, I had a powerful urge to cross the room and give the sister one hard slap. Just such an environment had led her brother to the threshold of death row; now she seemed oblivious to its effect on her children. My work is not all so strange. There are unexpected moments of grace. During one trial, I stood on the rainy courthouse steps as members of my clients family took a smoke break. Several family secretsa mothers attempted suicide, a robust family history of alcoholism and domestic abusehad just been revealed during testimony and would be

on the front page of the local newspaper by morning. There was quiet contemplation and some shrugs. One of the uncles caught my eye. A mill worker, he had thick hands roughened by the machines he had operated six days a week for the past 30 years. Is that Calvin Klein youre wearing? He was referring to my perfume. We began discussing the merits of various scents, from Poison to Carolina Herrera. He told me hed just switched to Comme de Garons. We laughed when we discovered that both of our fathers used Old Spice. Later, I thought about how skin color, money and culture make us so different, yet we can all be moved by a scent and the memories it carries with it. The job I had before this one was not exactly sheltered either. I investigated and wrote about human rights abuses in Peru and Colombia for an international human rights group. I interviewed paramilitaries and guerrillas, argued with generals, slipped into parishes to take down the stories of people with bounties on their heads. Occasionally, I lived the diplomatic high life, chatting up U.N. pashas, sipping cocktails at foreign embassies and mulling dessert lists at fancy restaurants. It was exciting work, exotic and full of the danger that puts a quasi-cosmetic glow on my cheeks. But after a while, I felt empty. Like the proverbial guest with good gossip, I felt that I was dining out too often on the misery of others. And I missed home. I decided that I wanted to live in my country like the people I admired in Colombia live in theirsfully engaged, clear-eyed and willing to take on unpopular causes. Honestly, it is hard to pick a more unpopular cause than defending accused murderers. My mother was not pleased. For years, she had worried as I flew into war zones and came back without a single story she could bear to hear. What happened to saving the whales? she asked me, remembering my teen passion. I could have trotted out a spiel on how it is critical in our democracy to fight for a fair justice system for all. Even for people who do despicable things. Especially when they do them. But a high ideal isnt what motivates me. It is the value of human life tucked like a note into the stories I hear. Behind the stone face, the tattoo, the swagger is the child who at five years of age would search out his drunken mother, coax her out of a ditch and guide her home. Here is the man whose first memory is of his fathers fist moving toward his face like the Apollo rocket, last launched the year he turned four. Here is the spelling bee champion who, at nine, was beaten senseless for moving the TV Guide. Here is the toddler whose mother sold him to pedophiles in exchange for drugs. These stories do not excuse murder. A murderer causes unspeakable pain in the families and the communities he harms. Murderers should be punished. Sometimes, they are so damaged that they cannot be allowed to rejoin society and must be imprisoned for the rest of their lives.

But for every seemingly remorseless killer like Scott Peterson, there are a hundred men on death row consumed with self-loathing and the inner torture of their own pasts. Their stories have taught me that their crimes are not committed in an instant, but created over years. In fact, in my sons elementary school, I can spot the children who may make my client list one day. A spectral hand seems to hang over them. They are the ones whose faces are closed at five years old. They are quiet but can erupt suddenly. For them, the English word tantrum is inadequate; what they have is rabia, rage. Friends assume I am working to free the wrongly accused, and there are some innocents in jail and on death row. But there are more men who admit their crimes. What is so compelling, at least to me, is how so many of them were made into criminals by their circumstances, assembled piece by piece, like Lego toys. Of course, there is free will and redemption and examples of people who overcome their lot and fashion law-abiding lives and even excel. But dont be fooled. Most of us are pulled down by hardship. Some of us dont survive. Sometimes the deck is stacked so thoroughly that it is a living miracle that any human feeling lingers in a drug-addled, abused and neglected brain. But the human spirit is hard to extinguish. With one client now on death row, I have an extensive and energetic correspondence about this very issue. He killed a woman, then turned himself in to the police. He says he regrets what he did every single day and every waking hour. But he rejects any suggestion that his upbringing in a household riddled by physical and sexual abuse, in one of the most violent urban slums in the United Stateshad anything to do with it. He is a true believer in the American ideal, the concept of an individual unhampered by race or gender or economic circumstance. And what about the victims? I also talk to their families to find out where they stand on the death penalty. A familys opposition can help gain clemency from a governor and save a clients life. But this is by far the most wrenching aspect of the work. Many families are not interested in talking to me, and that is their right. Others are, if only to find out what is going on with the case. Prosecutors represent the state, not the victims of crimes, and they spend little time keeping grieving families informed about new developments. Not long ago, I visited the mother of a woman shot and killed by one of my clients, the womans live-in boyfriend. The mother graciously allowed me into her home. We talked about her daughter and the status of my clients appeal. Around us swirled children and grandchildren, including the two boys left orphaned by my clients rage. While washing supper dishes, the younger boy feigned indifference but was intently listening to the adults talk. From the couch, the older boy glowered. He was the angry one, his memories of his mother still fresh. Still, I was comforted by their presence. I saw nothing of that spectral hand on these boys. Their grandmother wept. I wept. I touched their deepest wound, covered but never to be healed. The victims brother, a thick-set, powerful-looking man, told me he wanted my

client to die and cited the Bible as support. His mother also cited the Bible, but to express forgiveness and a desire that my client live. There was no struggle or argumentthey each had their own way of resolving the loss. Out of respect and a shared pain, neither presumed to dictate what the other should feel. It was one of the gentlest expressions of love between a mother and son that I have seen. I dont know how long Ill keep doing this work. Sometimes the weight of it feels real, like a load I cannot set down. But then, other times, when I least expect it, it lifts me.

Você também pode gostar

- The Black Hand: The Story of Rene "Boxer" Enriquez and His Life in the Mexican MafiaNo EverandThe Black Hand: The Story of Rene "Boxer" Enriquez and His Life in the Mexican MafiaNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (39)

- General Speech Rubric Wedding One PageDocumento2 páginasGeneral Speech Rubric Wedding One Pageapi-233206899100% (1)

- Sample Formal Report Student 2Documento17 páginasSample Formal Report Student 2Thalia SandersAinda não há avaliações

- Part A in What Situation Is English (Or Would English Be) Useful For You? Please Check The Appropriate ColumnDocumento8 páginasPart A in What Situation Is English (Or Would English Be) Useful For You? Please Check The Appropriate ColumnFarid HajisAinda não há avaliações

- 1 Shs Daily Lesson Log DLL Template Oral CommunicationDocumento12 páginas1 Shs Daily Lesson Log DLL Template Oral CommunicationKristine Bernadette MartinezAinda não há avaliações

- Listening Process-: Principles of Teaching Listening and Speaking SkillsDocumento19 páginasListening Process-: Principles of Teaching Listening and Speaking SkillsOmyAinda não há avaliações

- Contest Piece For The Oratorical ContestDocumento5 páginasContest Piece For The Oratorical ContestKlaus AlmesAinda não há avaliações

- Declamation PieceDocumento3 páginasDeclamation PieceJarby Vann CapitoAinda não há avaliações

- Grade 1 To 12 Daily Lesson LOG Comprehensive High School Sheila L. Lutero Context (First Semester)Documento3 páginasGrade 1 To 12 Daily Lesson LOG Comprehensive High School Sheila L. Lutero Context (First Semester)sheilaAinda não há avaliações

- The Pang of Misfortune - Declamation PieceDocumento2 páginasThe Pang of Misfortune - Declamation Piecemiathemermaid100% (1)

- Assessing GrammarDocumento24 páginasAssessing Grammarcahaya288Ainda não há avaliações

- GRADE 11/12 Daily Lesson Log: Creative Writing Monday Tuesday Wednesday Thurday Friday I. ObjectivesDocumento3 páginasGRADE 11/12 Daily Lesson Log: Creative Writing Monday Tuesday Wednesday Thurday Friday I. ObjectivesRachel Anne Valois Lpt100% (1)

- Q1 Week 2 Lesson 1.2Documento53 páginasQ1 Week 2 Lesson 1.2Isay SeptemberAinda não há avaliações

- Eng4 Final Persuasive Speech RubricDocumento1 páginaEng4 Final Persuasive Speech RubricAlyssa Joyce PenaAinda não há avaliações

- Communicative StrategyDocumento2 páginasCommunicative StrategyJulieSanchezErsando100% (1)

- Grade 9 Passive VoiceDocumento5 páginasGrade 9 Passive VoiceMarkbrandon0% (1)

- OCC Module 6Documento11 páginasOCC Module 6Jan MykaAinda não há avaliações

- 2 Intonation and StressDocumento27 páginas2 Intonation and StressdiwiyanaAinda não há avaliações

- DLP - Creative Writing - Detailed LPDocumento6 páginasDLP - Creative Writing - Detailed LPAgnes Asuncion VelascoAinda não há avaliações

- Oral Communication in Context 2 Quarter ExamDocumento3 páginasOral Communication in Context 2 Quarter ExamCleo DehinoAinda não há avaliações

- DLP OralDocumento2 páginasDLP Oralrogelyn samilinAinda não há avaliações

- Assessing Listening and Speaking Skills 1Documento49 páginasAssessing Listening and Speaking Skills 1NurSyazwaniAinda não há avaliações

- Oral Comm Mod 2Documento7 páginasOral Comm Mod 2Trisha Cortez100% (1)

- Linguistic Varieties and Multilingual NationsDocumento14 páginasLinguistic Varieties and Multilingual NationsSyaifuddin NoctisAinda não há avaliações

- DLL Oral Comm Week 3Documento5 páginasDLL Oral Comm Week 3Foreign Mar PoAinda não há avaliações

- Entertainment Speech Group4Documento15 páginasEntertainment Speech Group4klein 한번Ainda não há avaliações

- What Is Text, Discourse DefinedDocumento2 páginasWhat Is Text, Discourse DefinedChristine BlabagnoAinda não há avaliações

- Daily Lesson Plan 11 Oral Communication in Context First ObjectivesDocumento2 páginasDaily Lesson Plan 11 Oral Communication in Context First ObjectivesMaAtellahMendozaPagcaliwaganAinda não há avaliações

- Grades 1 To 12 Daily Lesson LogDocumento3 páginasGrades 1 To 12 Daily Lesson LogJeryn Ritz Mara HeramizAinda não há avaliações

- Tesol Letter of IntentDocumento3 páginasTesol Letter of Intentayoub1984Ainda não há avaliações

- Adapting MaterialsDocumento2 páginasAdapting MaterialsJuan Carlos Salazar GallegoAinda não há avaliações

- Department of Education: Inventory of Learning Resources Melcs-Based Oral Communication in ContextDocumento2 páginasDepartment of Education: Inventory of Learning Resources Melcs-Based Oral Communication in ContextDarl Dela CruzAinda não há avaliações

- SEE 5, Structure of EnglishDocumento32 páginasSEE 5, Structure of Englisherica lusongAinda não há avaliações

- 21st Century Literature From The Philippines and The World (Hum1)Documento10 páginas21st Century Literature From The Philippines and The World (Hum1)Bridgett TrasesAinda não há avaliações

- Genre Analysis OutlineDocumento5 páginasGenre Analysis Outlineapi-271788026100% (1)

- OC DLL JuneDocumento4 páginasOC DLL JuneAdeline PascualAinda não há avaliações

- HST Teaching Presentation RubricDocumento2 páginasHST Teaching Presentation RubricRonald MatrizAinda não há avaliações

- Types of Speech StyleDocumento18 páginasTypes of Speech StyleShyrell CepilloAinda não há avaliações

- 4AS LP For Grade 11 SHS (Comm Models)Documento3 páginas4AS LP For Grade 11 SHS (Comm Models)Ralph LacangAinda não há avaliações

- H. Ventura, Balara Filters Quezon CityDocumento3 páginasH. Ventura, Balara Filters Quezon Citybernaflor pacantaraAinda não há avaliações

- The Direct Method of Teaching EnglishDocumento7 páginasThe Direct Method of Teaching EnglishVisitacion Sunshine BaradiAinda não há avaliações

- Q2 Week 7 21st CLDocumento3 páginasQ2 Week 7 21st CLRonald RomeroAinda não há avaliações

- Oral Comm Week 6Documento10 páginasOral Comm Week 6Joseph ChristianAinda não há avaliações

- Q2 LESSON 1 Writing A Close Analysis and Critical Interpretation ofDocumento11 páginasQ2 LESSON 1 Writing A Close Analysis and Critical Interpretation ofColeen Faye NayaAinda não há avaliações

- Grade 9-English Anglo-American Literature: Prepared By: Ms. Andreata Gleen-Naie B. PaniangoDocumento19 páginasGrade 9-English Anglo-American Literature: Prepared By: Ms. Andreata Gleen-Naie B. Paniango원톤면Ainda não há avaliações

- Dran, Which Means "To Do.": Ancient Greece Is Considered The Birthplace of Classic Western TheaterDocumento5 páginasDran, Which Means "To Do.": Ancient Greece Is Considered The Birthplace of Classic Western TheaterGeraldine Dadacay-SarmientoAinda não há avaliações

- Types of Speech StylesDocumento40 páginasTypes of Speech StylesChrisBaruelAinda não há avaliações

- Functions of Nonverbal CommunicationDocumento9 páginasFunctions of Nonverbal CommunicationayushdixitAinda não há avaliações

- Early Approaches To Second Language AcquisitionDocumento22 páginasEarly Approaches To Second Language AcquisitionAmaaal Al-qAinda não há avaliações

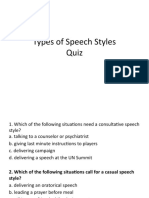

- Types of Speech Styles QuizDocumento6 páginasTypes of Speech Styles QuizAnais WatersonAinda não há avaliações

- Principles of Speech WritingDocumento16 páginasPrinciples of Speech WritingAriana CerdeniaAinda não há avaliações

- Teaching SpeakingDocumento36 páginasTeaching SpeakingTawanshine. penthisarnAinda não há avaliações

- Content of The Lesson PlanDocumento3 páginasContent of The Lesson Planapi-318034428Ainda não há avaliações

- Cefr ENDocumento1 páginaCefr ENhanminhtut.geniushmhAinda não há avaliações

- Grade 1 To 12 Daily Lesson LOG High School Sheila Lutero Week September 12 & 14, 2017 (Tuesday and Thursday/ 9:30-11:30a.m.)Documento3 páginasGrade 1 To 12 Daily Lesson LOG High School Sheila Lutero Week September 12 & 14, 2017 (Tuesday and Thursday/ 9:30-11:30a.m.)sheilaAinda não há avaliações

- Objectives: Voyages in Communication - English Learner's Module Grade 8Documento3 páginasObjectives: Voyages in Communication - English Learner's Module Grade 8Juan MiguelAinda não há avaliações

- The Suprasegmentals or Prosodic Feature of A Language.Documento29 páginasThe Suprasegmentals or Prosodic Feature of A Language.Franz Gerard AlojipanAinda não há avaliações

- The True Crime Dictionary: The Ultimate Collection of Cold Cases, Serial Killers, and MoreNo EverandThe True Crime Dictionary: The Ultimate Collection of Cold Cases, Serial Killers, and MoreNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (1)

- Decade of Chaqwa: Peru's Internal RefugeesDocumento42 páginasDecade of Chaqwa: Peru's Internal RefugeesRobin KirkAinda não há avaliações

- Sugar PopDocumento6 páginasSugar PopRobin KirkAinda não há avaliações

- The Dark ArmyDocumento5 páginasThe Dark ArmyRobin KirkAinda não há avaliações

- Human Rights As A Contest of MeaningsDocumento5 páginasHuman Rights As A Contest of MeaningsRobin KirkAinda não há avaliações

- The Treaty of Hopewell: 1785Documento5 páginasThe Treaty of Hopewell: 1785TRAVIS MISHOE SUDLER I100% (4)

- (CRIM 1) Articles 6-8 Case Digests PDFDocumento16 páginas(CRIM 1) Articles 6-8 Case Digests PDFRubyAinda não há avaliações

- Fulltext Crim Olazo-Sea Lion CaseDocumento79 páginasFulltext Crim Olazo-Sea Lion CaseFritzie G. PuctiyaoAinda não há avaliações

- Nilo Macayan, Jr. vs. People of The PhilippinesDocumento15 páginasNilo Macayan, Jr. vs. People of The PhilippinesAlexandra GarciaAinda não há avaliações

- G.R. No. L-2161-Pp Vs Young 93 Phil 702Documento4 páginasG.R. No. L-2161-Pp Vs Young 93 Phil 702mae ann rodolfoAinda não há avaliações

- V Sriharan at Murugan v. Union of India & Ors.Documento20 páginasV Sriharan at Murugan v. Union of India & Ors.Bar & BenchAinda não há avaliações

- Naskah Ujian Akhir Sekolah Tahun Ajaran 2018Documento5 páginasNaskah Ujian Akhir Sekolah Tahun Ajaran 2018Atmi Sri DewiAinda não há avaliações

- PP V Rafael FullDocumento10 páginasPP V Rafael FullGeanelleRicanorEsperonAinda não há avaliações

- A. Identify The Following Thesis StatementDocumento3 páginasA. Identify The Following Thesis StatementJonathan23dAinda não há avaliações

- Juvinile Justice.Documento19 páginasJuvinile Justice.prakash DubeyAinda não há avaliações

- The Solicitor General For Plaintiff-Appellee. Ernesto D. Labastida, Sr. For Accused-AppellantDocumento6 páginasThe Solicitor General For Plaintiff-Appellee. Ernesto D. Labastida, Sr. For Accused-AppellantJohn WickAinda não há avaliações

- Appellation Proclamtion Declaration Change May 10 2023 Updated Feb 05 2024 Red Font2Documento9 páginasAppellation Proclamtion Declaration Change May 10 2023 Updated Feb 05 2024 Red Font2akil kemnebi easley elAinda não há avaliações

- UA 195-92 - Chile Death Penalty Juan Domingo Salvo Zúñiga.Documento3 páginasUA 195-92 - Chile Death Penalty Juan Domingo Salvo Zúñiga.Marcelo ChaparroAinda não há avaliações

- Sentences and SentencingDocumento3 páginasSentences and SentencingAnmol TanwarAinda não há avaliações

- Argumentative EssayDocumento2 páginasArgumentative EssayRain GuevaraAinda não há avaliações

- Death Penalty Research PaperDocumento5 páginasDeath Penalty Research Paperktchen91333% (3)

- People Vs RiosDocumento9 páginasPeople Vs RiosIsaias S. Pastrana Jr.Ainda não há avaliações

- People v. DimaanoDocumento8 páginasPeople v. DimaanoNikki Joanne Armecin LimAinda não há avaliações

- Article 21Documento50 páginasArticle 21UMANG COMPUTERSAinda não há avaliações

- Seminar Presentation 1Documento5 páginasSeminar Presentation 1SHRUTI SINGHAinda não há avaliações

- Paragraph QuestionsDocumento67 páginasParagraph Questionsapi-3771391Ainda não há avaliações

- Love of Neighbor: Submitted To: Ms. Ladylyn Mabutol Submitted By: John Israel SiaronDocumento6 páginasLove of Neighbor: Submitted To: Ms. Ladylyn Mabutol Submitted By: John Israel SiaronJohn Israel Siaron100% (1)

- Discussion Text Exercise 2Documento2 páginasDiscussion Text Exercise 2Diki Roy Nirwansyah100% (7)

- Article2-Right To LifeDocumento21 páginasArticle2-Right To LiferitaAinda não há avaliações

- Rights of The Child in IRANDocumento68 páginasRights of The Child in IRANImpactAinda não há avaliações

- Corporal Punishment Versus Capital PunishmentDocumento8 páginasCorporal Punishment Versus Capital Punishmentchinthaka18389021Ainda não há avaliações

- Human Rights Case DigestsDocumento9 páginasHuman Rights Case DigestsEduard Loberez ReyesAinda não há avaliações

- 100 People v. Capalac, 1117 SCRA 874Documento2 páginas100 People v. Capalac, 1117 SCRA 874Princess MarieAinda não há avaliações

- CRIM LAW 1 - Pre FiDocumento6 páginasCRIM LAW 1 - Pre FiTin AngusAinda não há avaliações

- People v. GundaDocumento4 páginasPeople v. GundaNetweightAinda não há avaliações