Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

Female Emancipation in Bahrain

Enviado por

Bahrain LiberalsTítulo original

Direitos autorais

Formatos disponíveis

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Female Emancipation in Bahrain

Enviado por

Bahrain LiberalsDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

FEMALE EMANCIPATION IN BAHRAIN: A TOOL FOR SOCIAL REFORM?

Magdalena Karolak New York Institute of Technology College of Arts and Science, Adliya, Kingdom of Bahrainmkarolak@nyit.edu; karolak.magdalena@gmail.com BAHRAIN: MODERNIZING THE TRADITIONAL SOCIETY Modernization is a concept that operates on two levels: economic and socio-political (Utvik, 2003, p. 44). Firstly, it occurs in the technological and economic sphere stimulating urbanization, industrialization and market economy. It is accompanied by profound changes in the social structure, where traditional order of society organized through family bonds and patron-client ties is slowly eroded. Social and family networks stemming from village or kinship relations become less important in the new urban environment. On a political level it is characterized by an increase in mobilization of society as well as by structuralizing and strengthening of the state apparatus. The processes of modernization accelerated since the 1970's have brought profound changes to Bahrain, yet due to the rapidity of these processes they were unable to fully reshape the social fabric. Thus, they led to deep inequalities and contrasts. Bahrain is a country at crossroads between tradition and modernity. In the area of politics, Nakhleh (1976) referred to this semi-modern system as "urban tribalism", adaptation of tribal traditions within a modern system of government. This model provides an accurate picture when transposed to other areas of society and applies to the position of women. Indeed, the fast growing and modernizing society has retained some of the tribal arrangements, which govern the social structure. Recent reforms initiated during the rule of King Hamad bin Isa Al Khalifa created new prospects for female empowerment in Bahrain. Indeed, "the country is making history by creating a new era where women [...] reach the goals that would have been unachievable in any other point in time." (SCW, n.d., p.1) On the other hand, long- standing traditions based on a patriarchal organization of society prevent women from becoming equal partners to men in Bahraini society. In order to assess the progress of female empowerment in Bahrain we shall analyze, in the first place, the traditional social bonds that regulate the position of women in society. Secondly, we will focus on the slow emergence of women as actors in the public sphere. Furthermore, we will assess large scale governmental initiatives that aim at

empowering women. Finally, we shall present an overview of the existing obstacles to full empowerment. Evaluation of women status in Bahraini society Within the legal framework rights of women in Bahrain are protected. The Constitution of Bahrain alludes to the role of women in society stating that "the State guarantees reconciling the duties of women towards the family with their work in society, and their equality with men in political, social, cultural, and economic fields without breaching the provisions of Islamic canon law (Shari'a)" [art. 5]. The Constitution guarantees also "that citizens, both men and women, are entitled to participate in public affairs and may enjoy all political rights" [art. 1e]. Furthermore, article 18 stipulates that "people are equal in human dignity and they are equal before the law in regards to their public rights and duties. No discrimination on the grounds of gender, origin, language, religion or belief is tolerated". Despite these legal provisions, empowerment of women faces challenges in the traditional societies in the Middle East, including Bahrain. As identified by Moghadam (2003) women in the Middle East, including Bahrain are lobbying for the changes related to: "(1) the modernization of family laws, (2) the criminalization of domestic violence and other forms of violence against women, (3) womens right to [] pass the nationality on their children, (4) greater access to employment and participation in political decision- making." (p. 279). These challenges are remnants of the tribal patriarchal structure of Arab societies, which proved particularly resistant to change. The effects of patriarchy weight heavily on women empowerment. Patriarchy is defined as "a hierarchy of authority that is controlled and dominated by the males"(Krauss, 1987, p. xii). It originates in the family, which forms a basic institution of Arab societies. Families are headed by men and within this patriarchal structure female and male obligations and spheres are strictly separated (Giacaman, Jad, &Johnson, 1996). Within patriarchal structures "family is also central to political identity. Political identity comes through male genealogy. The Arab nation is seen as descending through a series of patrilineal kin groups. Citizens have to belong to a male-defined kin group to belong to a religious sect, to belong to the nation, and to acquire the rights and responsibilities of citizenship. Children are assigned both the religious and political identities of their fathers. By not allowing women to pass citizenship on to their children (or their spouses), most Arab states cement

the linkage between religious identity, political identity, patrilineality, and patriarchy that is, between religion, nation, state, and kinship" (Hijab, 2002). Traditional division of roles sees women's fulfillment in the area of home as mothers and wives (Sabbagh, 2007). Family ought to create a safe zone within which women find protection. Women's subordinate position is justified this way. Although identifying women inequality with Islam is misleading, some aspects of Islam contribute to male domination in society. Legal system in Bahrain is, for example, a mix of western legal standards, tribal laws combined with sharia, a of set religious laws based on the interpretation of Quran, that treats men and women in a different manner. Despite rapid modernization of the country, female participation in society has been increasing slowly in Bahrain. Unprecedented economic boom of the Gulf region experienced in the 1970s did not really open doors for female participation in society. In the 1970s women made up only for 4 % of total workforce (SCW, 2001). Ross(2008) argued that oil rentierism is the cause of limited economic and political participation of women in the Middle East. Oil industry requires male labor and reduces female activity in the workforce. Consequently, women concentrate on running the households, which leads to higher fertility rates and limits possibilities of information exchange and thus political organization. Initially, the economic growth did not erode the tribal social structures that keep women outside the public sphere. On the contrary, it strengthened them by providing enough resources to families to rely solely on men's work. However in 2010, female participation in workforce rose to around 32.1% (Bahrain Economic Development Board, 2010). With longer education and professional careers on the rise, fertility rates dropped from 7.09 children per woman rate in 1960s to 2.29 in 2007 (World Bank, 2009). It is important to analyze how these social changes combined with recent reforms affected the position of women in Bahraini society. Female empowerment in Bahrain: initial overview Middle East and North Africa (MENA) is characterized by an unequal female participation in the public sphere. Recent analyses highlight substantial advancements of female empowerment in certain areas, which can "compare favorably with those of other regions" (World Bank, 2004). However inequalities between genders persist and hinder the development of the region. Moreover, patterns of female empowerment in MENA are in sharp contrast with the experiences observed in other regions of the world. Indeed "womens gains in health and education in other parts of the world have been matched by

gains in economic and political participation to a much greater degree than has been the case in the Arab states" (United Nations, 2007). Bahrain is no exception to this gender paradox. The Global Gender Gap Report, a tool developed in 2005 by the World Economic Forum offers interesting points of comparison throughout the years 2006-2010. In the area of health and survival as well as educational attainment, Bahrain has positioned itself relatively high among the countries of the region. On a scale 0-1, where 1 means full equality of men and women, Bahrain scored respectively 0.9612 and 0.9915 in 2010. Although since 2006 Bahrain has slightly fallen in the world ranking, its achievements in both areas are noteworthy. Nonetheless, Bahrain, along with other Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) countries, represents a peculiar case since participation of women in the economy has been steadily rising in recent years. On the contrary, female political involvement remains comparatively low. In the year 2006, in the area of economic participation and opportunity Bahrain scored 0.3829, while in the area of political empowerment 0.0236. In 2010, these scores were improved and reached, respectively,0.4967 and 0.0376 (The Global Gender Gap 2010 Report). Although significant advancements were made in the area of economic activity, political advancement falls clearly behind. It is important to underline that the indicators discussed above are, in major part, a reflection of the policies adopted by Bahraini authorities and their impact on the society. Recent reforms focused, on the one hand, on greater inclusion of women in the public sphere promoting their participation in the economic and political processes. On the other hand, new legislation allowed for codifying the status of women within family law. ROLE OF BAHRAINI AUTHORITIES IN WOMEN EMPOWERMENT Bahraini authorities play the role of actively promoting female empowerment. The importance of the cause was highlighted through the establishment of an organization dedicated especially to gender equality and the empowerment of women, the Supreme Council for Women (SCW) in 2001. SCW is a quasi-governmental body advisory to the king, headed by the king's first wife Sheikha Sabeeka bint Ibrahim Al Khalifa. It is dedicated to, between the others, promoting inclusion of women in the decision making positions, improving skills of women, creating job opportunities, conducting studies, as well as organizing awareness campaigns aimed at women. Among many tasks, SCW has been overseeing the implementation of the provisions of the Convention on Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women(CEDAW) agreement, within the limits of the sharia.

The other important initiative is the National Strategy on the Empowerment of Bahraini Women, conducted with the support of United Nations Development Programme (UNDP). It includes programs on enhancing economic and political empowerment of women that are carried out over the years 2009-2012. Moreover, SCW carried out a strong campaign to support the unified personal status law and subsequently, implementation of the law for the Sunni branch of Islam.

Economic empowerment Economic empowerment of women is part of the "Bahrain Economic Vision 2030", a broad initiative of development of the country unveiled in 2008. Oil depletion as well as soaring unemployment rates among Bahraini nationals demanded a shift in policies related to job market strategy (Bahrain Unemployment..., 2005). Sustainable development independent from oil resources and competitiveness are a must for future growth of the GCC region overall. Given the fact that women account for 70%of all university graduates (BEDB, 2009), Bahraini authorities saw womens rising education attainments as a resource for the country's development (SCW, n.d.).Indeed, international studies suggest that low participation of women in the workforce has a direct negative impact on the country's GDP (Lfstrm, 2009). Moreover, case studies assert that female participation in business ownership has an even stronger correlation with GDP growth (Weeks & Seiler, 2001). Tamkeen, an employment agency developed under the umbrella of the government, promotes greater inclusion of Bahrainis in the economy through multiple initiatives. It provides job training as well as training and employment programs in cooperation with Bahraini-based companies, scholarships, funding for enterprises and skill improvement programs. Tamkeen adopted in collaboration with SCW a special approach to increase female employability, including increasing the number of women in male-dominated fields of economy. This comes as an important step given that women constitute the majority of the unemployed. In 2009 and 2010 women constituted roughly 80% of the unemployed (Al Gharaibeh, 2011). The joint cooperation between Tamkeen and SCW awarded grants to women entrepreneurs in the fields of transportation, fashion design and photography. An all female job and training exhibition for the unemployed took place in 2010, while the theme for Bahraini Women Day's for 2011 was "The Bahraini Woman and her role in supporting the National Economy". As a result of cooperation between Tamkeen and Bahrain Women's Union, a computer skills training program for women wasestablished. So far, 11,782 women

have benefited from multiple programs organized by Tamkeen (Trade Arabia, 2011). New legislation encourages also the employment of Bahraini women, as in the process of nationalization of the workforce, each women counts as two local employees allowing companies to achieve their Bahrainization rates faster. Economic advances in Bahrain were strengthened by female business activity. Eased procedures that allowed women to process all paperwork themselves instead of male representatives boosted female entrepreneurship (Ahmed, 2010). In 2008 more than one third of Bahraini businesses were owned by women (Gender Gulf, 2008). On the other hand, since 1997 Micro Start project aims at economically empowering needy households. Developed jointly with the UNDP, it is addressed in particular to women who, so far, benefited 73% of all distributed loans in Bahrain. The program allows them to become productive and independent from income earned by men. Political empowerment Similarly, womens participation in politics would not have been possible without an active support of Bahraini authorities. Apart from obtaining suffrage right as well as the right to stand for elections to the lower house of the Bahrain Parliament in 2002,women were appointed in prominent public offices. Cabinets in 2002 and 2006included women as minister of health, minister of social affairs and minister of culture and information. Women were also appointed in the Shura Council, the upper chamber of the Parliament. Moreover, women represented Bahrain on an international scene. In 2000 first woman Sheikha Haya Rashed Al Khalifa became a Bahraini ambassador. She was subsequently elected a president of the UN General Assembly. In 2004 women were appointed in the GCC Consultative Corporation. However, these symbolic nominations would not be sufficient to promote participation of women in society overall. Thus, before the 2006 and the 2010 parliamentary elections SCW conducted political empowerment programs providing women with training necessary skills as well as funding to support their political campaign. The goals of such initiatives included altering of social attitudes and stereotypes towards women as well as supporting participation of women in the Parliament and the Municipal Councils(Action Plan for Political Empowerment of Women, 2002). Measuring the progress: a comparison The outcomes of governmental policies vary since regulations that stem from above are not necessarily readily accepted by the public. The opposition towards women business

activity is muted. Women in Bahrain have already had the right to own property and to open a bank account, which could ease their transition to businesswomen. Moreover, wife of the Prophet Muhammad, Khadija is often presented as an uncontested proof of female business activity and as a figure of economic empowerment, while in politics such strong symbols lack. Subsequently, women entering politics faced challenges from various segments in society. To begin with, the king's decision to grant women suffrage rights met an opposition of 60% of Bahraini women (Janardhan, 2005). Female candidates running in the elections were breaking an established social order, which caused tensions. In 2002 and in 2006elections many female candidates felt a direct pressure to withdraw put on them by male candidates in electoral districts (Toumi, 2006). Moreover male candidates used traditional division of gender roles to discredit their female opponents. Sunni Islamist candidate Ebrahim Bousandal addressed voters stating that women should not take part in politics because their place was at home (Intelligent, ambitious..., 2010). In2006 female candidates received phone messages threatening them to withdraw immediately from the race (Bille & Moroni, 2006). During electoral campaign of that year acts of vandalism were committed. Fawzia Zainal's campaign tent was set on fire. She claimed as well to have been targeted by derogatory gossips (Grewal, 2010).Furthermore, women were unable to secure the support of major political associations that are Islamic in nature. None of the Islamic associations endorsed female candidates. So far, only one woman Latifa Qaoud has been elected to the parliament in general elections in 2006 and in 2010. Although she was the first woman MP elected in the GCC, she ran both times unchallenged and represented scarcely populated and remote islands of Al Hawar. The example of politics represents an area where there is strong resistance to change. Nonetheless, participation of women in elections had an important effect on Bahraini society. In 2010 the level of social acceptance of women candidates has increased. Women did not face criticism or intimidation, which proves that voters acknowledged their active role in the political process. Moreover, in 2010 Latifa Salman a candidate in the municipal elections, became the first Bahraini woman to win a popular election, while directly challenging a male candidate. Women's achievements in breaking the gendered stereotypes are highlighted in the local media. Newspapers devoted several articles to present female candidates in the national elections and closely followed their campaigns. Similarly, women who break into the traditionally male dominated jobs, such as female judges or female pilot are highly praised and draw a lot of attention. (New crop..., 2010). Encouragement plays no doubt an important role in publicizing women's achievements in the society however certain areas

remain heavily male-dominated. Sector of education and healthcare are feminized, whereas the number of men exceeds that of women in all other fields and is especially acute for example in engineering (Ahmed, 2010).The path to full empowerment is not complete, however once this process has been started, it will certainly bring further positive outcomes as observed below: "Women are slowly emerging as political leaders in a region that has long been a bastion of male power.[...]. Once invisible, women are gradually realizing their political potential [...]"(Women in Parliament ...). Empowerment within family The problem of codifying the legal rights of women with relation to marriage, divorce and child custody caused a heated debate within Bahraini society. Bahraini activists since the 1980's have tried to exert pressure on the government to allow for creation of a Personal Status Law that would protect women. Although civil courts exist in Bahrain, all matters related to family are referred to sharia religious courts headed by clergymen. These courts are separate for Sunni and Shia sects of Islam and apply their own interpretations of sharia. Discriminatory practices in sharia court rulings are common. Due to the lack of a written law, all court rulings are subject to personal interpretation. This leads to a lack of consistency, rampant contradictions, and moreover, to a gender bias since judges would usually side with men. The effects of these practices on women are detrimental. Women would endure hardships to be granted a divorce if they initiated it and the proceedings could take up to ten years (Personal, Family and Legal Status of Bahraini Women, 2008). They could be easily deprived of custody of their children; unable to claim alimony or would be granted insufficient funds. Ultimately, the husbands could prevent their wives from living in the same house forcing them to move in with relatives. Since Bahraini civil courts do not have jurisdiction over sharia court, it is not possible to appeal an unjust verdict. Since its establishment SCW campaigned for a unified written law and took on a task to prepare a draft. Drafting the law created tensions between female activists and conservative clergy. The firm opposition of Shiite scholars caused the draft committee to abandon the idea of a unified law in favor of a Sunni version only. Consequently, the first written law called Family Provision Act (Law 19/2009) passed in May 2009 applies to Sunni sect. The law1 brought important regulations to protect rights of women related to marriage, divorce and child custody. Within the marriage contract women can stipulate that they do not allow their husbands to marry additional wives. Both parties can specify in the marriage contract terms and conditions related to family expenditures, housing as well as

employment and education. Furthermore, the new law specified cases where women are rightfully entitled to seek divorce such as lengthy imprisonment of the husband, drug addiction ,abandonment of the family and lack of financial support as well as discord and harm between husband and wife. Moreover, judges are allowed to consult psychologists and social workers when ruling custody of children keeping in mind the best interest of child. The law entitles women granted custody to entail housing provided by the father of children as well as to seek alimony. The court may also order DNA tests to establish parenthood. The SCW has undertaken a long-term study to analyze the impact of the new law on lives of Bahraini women. It is important to note however that the Family Provision Act does not establish equality between genders. A woman, for example, still requires the consent of a guardian to get married even though there are amendments to the role of the guardian in the marriage process. Similarly, the law makes a difference between divorces initiated by men and by women, since women have to provide legal grounds to ask for it. The effects of this law are also limited by the fact that it applies to Sunni sect only. Shia sharia courts continue exercising jurisdiction based on the traditional interpretation of the Islamic law. MODERN TRIBALISM Despite improvements, empowerment of women is hindered by a number of obstacles, which stem mostly from long-standing traditions and gender stereotyping. Consequently, the impact of newly introduced reforms is sometimes limited and changes occur at a slow pace. Furthermore, while there are significant improvements in certain areas, others fall significantly behind. These cases include lack of inadequate legislation to fully protect the status of women or application of legislation that holds back the empowerment of women. The reasons for and this uneven state of affairs and its consequences need to be examined in detail. Data collection revealed particularities in the problems encountered by Bahraini women. A brief overview is presented below. Nationality Even though Bahrain has adopted progressive legislation that guarantees equality of genders, Bahraini women cannot pass citizenship on their foreign husbands and on their children born from such marriages. The battle of female rights activists and SCW to amend the Article 4 of the 1963 the nationality law has led to slight improvements. The latest legislation allowed Bahraini women to sponsor their husbands' and children's residence in

Bahrain under certain conditions. Children can enjoy exemptions from fees for government as well as healthcare and education benefits equal to Bahrainis if they reside in the kingdom, however they are excluded from political, employment and housing benefits. This patriarchal approach to nationality was recently reaffirmed. In the royal decree to grant all Bahraini families a gift of 2650 USD on the tenth anniversary of the National Action Charter in February 2011,the term "Bahraini family" did not apply to families of Bahraini women married to foreigners and their children. Subsequently, they were not included in the cash payout. Labor market discrimination The Labour Act (Decree No. 23 of 1976) guarantees equality of all employees, however in the context of patriarchy women tend to be discriminated in the labor market with regards to remuneration as well as promotion opportunities. The gender pay gap is a sanctioned by gendered norms which assume that men ought to earn more since they are primary breadwinners for the family and women's job is a secondary source of income. Consequently, women's work is valued less and gets less recognition (Esplen & Brody, 2007). On the average, Bahraini woman earns 76% of the income of a male worker for similar job (Global Gender Report, 2010). In certain areas the inequalities are more rampant than in others. A study conducted in 2002revealed that in the private sector women earn 73% of men's salary in the administrative jobs, 61% in the services jobs, 55% in the scientific and technical jobs,46% in the transportation jobs, and 27% in the handicraft jobs (Korayem, 2007, p.6). Gender stereotyping has also a negative impact on promotion opportunities of women in the workplace. In a study conducted by SCW, 26.6% respondents agreed that there is discrimination in favor of men in promotion and appointments (Personal, Family and Legal Status of Bahraini Women, 2008). Although in the Global Gender Report Bahrain has significantly improved in the proportion of female legislators, senior officials, and managers that increased from 10% (2006) to 22% (2010); the proportion of female professional and technical workers slightly fell from 19% (2006)to 18% (2010). It is also not known how many appointments to senior position represented ad hoc practices and how they reflect aspirations of equality. Even though the general legislation supports the idea of gender equality, the labor laws "do not prohibit or provide protections against gender-based discrimination in the workplace" (Al Najjar, n.d.). Inheritance

Islamic sharia law governs inheritance and treats both genders separately. Women may inherit from fathers, mothers, brothers, husbands and children; however women's shares are significantly smaller than men's. The sectarian division complicates the matter since Sunni and Shia apply different set of rules. Daughters, in case of absence of a male child, can inherit full father's estate (Shia ruling) or they are obliged to share it with other paternal relatives (Sunni ruling). Under Shia laws, wives cannot inherit their husband's land but only movable assets, while under Sunni laws they can. In all cases, non-Muslim women cannot inherit from their Muslim husbands. The reason for women's different treatment in inheritance is directed by a different perception of social obligations in Islam. Men are held financially responsible for families needs.Women are supposed to be provided for by their fathers, brothers or sons and can, at least in theory, retain their earned money if they choose to work. Various sources suggest however that working women contribute to the daily household expenses, while in extreme cases they are forced to give up their salaries to their husbands (Al Najjar, n.d.). The increase of numbers of working women who are married from 45%in 1981 to 60% in 1991 may indicate that women's contribution to the family is increasing as well (Wilkenson & Atti, 1997). The expectations towards wives in Bahrain changed drastically as a number of respondents admitted that "young men nowadays look for a wife that can help with family expenses" (Kelly, 2009). Moreover, it is important to note that 10.84% of Bahraini families are supported by a woman. Violence against women The topic of violence-related problems within Bahraini families has only recently become open for public discussion. Domestic violence has been widely reported by women's rights organizations, which led to a growing awareness of the problem. The calls for criminalization of violence against women became vocal. This change of attitudes opened doors for debate in the media. Creation of centers of support for violence victims allowed not only providing help, advice and therapy but also for a better assessment of the problem. Until recently, victims would be condemned to suffer in silence due to social and religious pressure as well as lack of welfare organizations dedicated to the problem. The study conducted by the Batelco Centre for Family Violence Victims revealed that women still tend to tolerate abuse until domestic violence reaches unbearable limits as 75% of victims wait more than 10years to contact a support centre (Bahrain: Why women...). Women remain silent since they lack confidence in the legal system and fear negative consequences on their family. Indeed, the Penal Code, stipulates that "Nothing is considered a crime as long as it is the exercise of a right granted by law or custom" [art. 16].

Violence against women by male members of the family is accepted by conservative segments of society as a right to discipline the woman. The levels of the phenomenon are significant. Taking into account that most cases still remain unreported, statistics of the Batelco revealed 7503 cases of victims between 2007 and 2009 in the country of 568,399 Bahraini inhabitants (2011). Among the many types of abuse, in case of sexually motivated violence, Bahraini laws offer lowest protection for women. A rapist can escape punishment if he marries the victim, while spousal rape is not considered abuse since a husband has the right to execute his conjugal privileges even against the wishes of his wife. Recent cases highlighted by the media show also dangerous attitudes towards sexual crime victims. A Bahraini female lawyer defended suspects accused in gang rape of a Filipino stating that rape was just "fun" without criminal intent. A British victim of a gang rape claimed she was made to wait more than a week to undergo a medical exam. She was fired for reporting the case and the suspects freed due to inconclusive evidence. The fact that women affected were foreigners could act further in downplaying the crimes. Furthermore, the traditional view has it that women's behavior or appearance is an excuse in sexually motivated crimes. Studies suggest that violence against women is a widespread phenomenon as 88.4 % of respondents perceive it in the workplace and public places (Personal, Family and Legal Status of Bahraini Women, 2008). Bahraini laws continue to offer insufficient protection as legislation punishing acts of violence against women was ranked both, in 2006 and 2010, 0.75 on a scale from 0 to 1, where 1 means worst case scenario (The Global Gender Gap Report, 2006 & 2010). Attitudes towards female empowerment Evolution of traditional approaches to gender depends also on the change of attitudes among women towards female empowerment. However, Sabbagh (2007) points out that "womens daily lives and practices are reinforcing patriarchy". Indeed, in recent years women have supported views that reduce their ability to become full actors in the public sphere. For instance, 60% of Bahraini women opposed obtaining full political rights in 2002 and entering what is traditionally regarded to be a male sphere (Janardhan, 2005). Women's issues have been also used for political purposes (Kinninmont, 2011). In 2005 the Shia opposition groups organized a demonstration against the introduction of the personal status law for Shiites. They mobilized 120,000 protesters, mostly women. Women's rights organizations gathered only 500 people in support of the law (Ahmed, 2010). While

progressive activists call for ijtihad, reinterpretation of the Quran within the modern context, conservatives support the traditional application of the norms and reject claims of historical adaptation. The change could be brought about thanks to the commitment of SCW and Bahraini NGOs. The nineteen women NGOs include, between the others, Bahrain Businesswomens Society, Bahrain Women's Association for Human Development, Bahrain Womens Association, Womens Petition Committee, New Dawn Ladies Society Bahrain Womens Society, Awal Womens Society, Madinat Hamad Women's Society, Fatat Al-Reef, Riffa Cultural Charity Society and the Mustaqbal Society. Twelve societies are loosely organized under the umbrella of Bahrains Womens Union. The goals of women NGOs vary greatly, however all support a growing awareness of Bahraini women through workshops, training, debates or consultations. In total 4,000 women constitute over 60 % of membership of all Bahraini NGOs (Ahmed, 2010). Conclusion Full empowerment of women in Bahraini society is a lengthy process that is hampered by gender stereotyping due to long-standing traditions based on patriarchy. Recent governmental initiatives provide foundation to female leaders by changing the negative impact of patriarchy. On the other hand, remnants of tribal practices that discriminate women persist. They seem to have been widely accepted in society, including by many women. The work of NGOs can play an important role in raising awareness of women and to exert pressure for changes. However, women NGOs still do not have sufficient membership to mobilize large segments of society. Despite shortcomings, Bahrain can serve as a model of changing female role in the Gulf region.

Notes 1. Full text is available on-line in Arabic http://www.gcclegal.org/mojportalpublic/DisplayLegislations.aspx?country=6&LawTreeSectionID=9969

Bibliography

Action Plan for Political Empowerment of Women. (2002). Retrieved January 6, 2011, from http://www.undp.org.bh/Files/APW/46688.pdf Ahmed, D. A. A. (2010).Womens Rights in the Middle East and North Africa: Bahrain. Washington, DC: Freedom House.14 Al Najjar, S. (2009). Bahrain. Washington, DC: Freedom House. Bahrain Economic Development Board (BEDB). (2009). Bahrain leads the way in building capabilities of women. Retrieved January 6, 2010, from www.bahrainedb.com Bahrain Economic Development Board (2010). 4% Growth in Economy and Bahraini Workforce . Retrieved 12 February, 2011, from http://www.bahrainedb.com/enewsletter/en/default.asp?action=article&id=70 Bahrain Unemployment A Time Bomb, 2005, February 28, APS Diplomat Strategic Balance in the Middle East . Retrieved January 6, 2010, fromhttp://www.allbusiness.com/government/343553-1.html Bahrain: Why women are suffering silently . Retrieved January 6, 2010, fromwomensphere.wordpress.com/page/99/?archives-list=1 Bille, S. & Moroni, E. (2006). Report on Elections in the Arab World 2006 a Human Rights Evaluation. Amman Center for Human Rights Studies. Dunne, M. (n.d.). Women's Political Participation in the Gulf: A Conversation with Activists Fatin Bundagji (Saudi Arabia), Rola Dashti (Kuwait), Munira Fakhro(Bahrain) . Retrieved December 11, 2009, from Carnegie Endowment for International l Peace Web site: http://www.carnegieendowment.org/ Esplen, E., & Brody, A., (2007). Putting gender back in the picture: Rethinkingwomens economic empowerment. In Bridge report: Institute of Development Studies University of Sussex,19, pp.1-49. Al Gharaibeh, F. (2011). Womens Empowerment in Bahrain. Journal of International Women's Studies, 12 (3), pp. 96-113. Gender Gulf (April 10, 2008).The Economist.

Giacaman, R., Jad, I. & Johnson, P. (1996). For the Public Good? Gender and Social Citizenship in Palestine. Middle East Report . No. 198. Vol 26. No.1. Pp. 11-17. Grewal, S. S. (October 09, 2010). Election quota for women plea. Gulf Daily News .

Hijab, N. (2002).Women Are Citizens Too: The Laws of the State, the Lives of Women. New York: Regional Bureau for Arab States, UNDP. Intelligent, ambitious 12 Bahraini women fight stereotypes, stand for parliamentary elections (4 October, 2010). Retrieved 25 March, 2011, fromhttp://www.muslimsdebate.com/faces/sn.php?nid=1059 Janardhan, N. (2005, June 20). In the Gulf Women Are Not Womens Friends. The Daily Star. Kelly, S. (2009). Recent Gains and New Opportunities for Womens Rights in the Gulf Arab States, in Womens Rights in the Middle East and North Africa: Gulf Edition.Freedom House. Kinninmont, J. (2011). Framing the Family Law: A Case Study of Bahrain's Identity Politics, Journal of Arabian Studies, 1(1), 53-68. Korayem, Combating Poverty of Bahraini Females; Identification, Assessment, and Policy Recommendations, a Report prepared for the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), Bahrain Office and the Supreme Council for Women, Kingdomof Bahrain, 2007. Krauss, P. R. (1987).The Persistence of Patriarchy: Class, Gender, and Ideology in Twentieth Century Algeria. New York: Praeger. Lfstrm, A. (2009).Gender Equality, economic growth and employment . Swedish Ministry of Integration and Gender Equality. Moghadam, V. M. (2003). Modernizing women: Gender and social change in the Middle East . Boulder: Lynne Rienner Publishers, Inc . Nakhleh, Emile A. Bahrain: Political Development in a Modernizing Society. Lexington, MA: Lexington Books, 1976.

New crop of Arab women pioneers are soaring into a man's world (2010, January 22).Gulf Daily News, 2A. Personal, Family and Legal Status of Bahraini Women (2008). Bahrain Women's Union. Ross, M. L. (2008). Oil, Islam, and women. American Political Science Review ,102(1),107123. Sabbagh, A. (2007). Overview of women's political representation in the Arab Region: opportunities and challenges. The Arab quota report: selected case studies .Stockholm, Sweden: IDEA - International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance: pp. 7-18. Supreme Council for Women (n.d.) Statistics on Bahraini Women. The Global Gender Gap 2010 Report (2010). Geneva: World Economic Forum. The Global Gender Gap 2006 Report (2006). Geneva: World Economic Forum. Toumi, H. (November 25, 2006). Female hopefuls counter traditional roles. Gulf News. Trade Arabia (2011).Tamkeen skills drive a 'boon for Bahraini women' . Retrieved June 28, 2007, from http://www.tradearabia.com/news/EDU_193323.html16 United Nations (2007). Gender Equality Part Three Political and Economic Participation. ESCWA - Center for Women Newsletter . 2(13). Weeks, J. & Seiler, D. (2001). Womens Entrepreneurship in Latin America: An Exploration of Current Knowledge. Inter-American Development Bank. Wilkenson, B., Atti, A. (1997). UNDP microfinance assessment report for Bahrain. United Nations Capital Development Fund. Retrieved August 28, 2007, fromhttp://www.uncdf.org/english/microfinance/uploads/country_feasibility/bahfinaldb.pdf Women in Parliament in 2006: The Year in Perspective. (2006). Retrieved 5 February, 2011, from http://www.ipu.org/pdf/publications/wmn06-e.pdf World Bank. (2004).Gender and Development in the Middle East and North Africa: Women and the Public Sphere. Retrieved 5 February, 2011, fromhttp://go.worldbank.org/ENRPGWBY40 World Bank Development Indicators (2009). Washington: The World Bank.

Você também pode gostar

- Gender Inequality in The MENA Region Fall 2021Documento63 páginasGender Inequality in The MENA Region Fall 2021Yasmin HusseinAinda não há avaliações

- CertificateDocumento1 páginaCertificateAjay Dada GaykarAinda não há avaliações

- PDFDocumento6 páginasPDFAjit RaoAinda não há avaliações

- Bihar Birth CertificateDocumento1 páginaBihar Birth CertificateKAMAL SONIAinda não há avaliações

- eTAX Terms & ConditionsDocumento4 páginaseTAX Terms & ConditionsAccounts100% (1)

- Shanti Vihar FormatDocumento6 páginasShanti Vihar FormatAbhimanyu ChauhanAinda não há avaliações

- Payslip Feb 2022Documento1 páginaPayslip Feb 2022PRASHANT BANDAWARAinda não há avaliações

- PORTFOLIODocumento7 páginasPORTFOLIOismail abidAinda não há avaliações

- Anuj ASAPM2826N ITR-VDocumento1 páginaAnuj ASAPM2826N ITR-Vapi-27088128Ainda não há avaliações

- Statement of Account for Vinod Kumar PurbeyDocumento4 páginasStatement of Account for Vinod Kumar Purbeyshreya.pAinda não há avaliações

- Presentation Made To Analysts / Investors (Company Update)Documento20 páginasPresentation Made To Analysts / Investors (Company Update)Shyam SunderAinda não há avaliações

- Account Statement 151020 310122Documento243 páginasAccount Statement 151020 310122Subhash MauryaAinda não há avaliações

- Loan Offer LetterDocumento6 páginasLoan Offer LetterGyanendra KcAinda não há avaliações

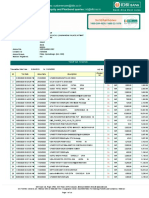

- Statement of Account: Date Narration Chq./Ref - No. Value DT Withdrawal Amt. Deposit Amt. Closing BalanceDocumento34 páginasStatement of Account: Date Narration Chq./Ref - No. Value DT Withdrawal Amt. Deposit Amt. Closing BalanceMehndi HasanAinda não há avaliações

- 1448 Sadab Sayed-Quess Corp (MCA) 2019-2020Documento8 páginas1448 Sadab Sayed-Quess Corp (MCA) 2019-2020Venkatesh BathulaAinda não há avaliações

- MDU Result for CHITRA (Reg. No. 2111291091Documento3 páginasMDU Result for CHITRA (Reg. No. 2111291091Chitra ParmarAinda não há avaliações

- Legal Barriers To Gender Equality in Inheritance in The Maghreb RegionDocumento72 páginasLegal Barriers To Gender Equality in Inheritance in The Maghreb RegionFIDHAinda não há avaliações

- New Joiner Handbook-BLRDocumento22 páginasNew Joiner Handbook-BLRsreem naga venkata shanmukh saiAinda não há avaliações

- Statement of Account No:922010005446977 For The Period (From: 09-02-2022 To: 08-05-2022)Documento3 páginasStatement of Account No:922010005446977 For The Period (From: 09-02-2022 To: 08-05-2022)Pradeep Kumar mohantyAinda não há avaliações

- PDFDocumento3 páginasPDFRISHI KEJRIWALAinda não há avaliações

- NiyoX-Statement-Jayavani M-01Sep22 - To - 30nov22 - 3cwp9zqDocumento26 páginasNiyoX-Statement-Jayavani M-01Sep22 - To - 30nov22 - 3cwp9zqRicha BehraAinda não há avaliações

- Annual bank statement for Samepal SinghDocumento10 páginasAnnual bank statement for Samepal SinghIshandhankharAinda não há avaliações

- Srinivasa Gupta StatementDocumento16 páginasSrinivasa Gupta StatementSrinivasa GuptaAinda não há avaliações

- RTPS Nec 2023 3581289Documento1 páginaRTPS Nec 2023 3581289Mahammad HachanAinda não há avaliações

- Jmiv Yq 9 Idi Gvy KKTDocumento2 páginasJmiv Yq 9 Idi Gvy KKTVara Prasad AvulaAinda não há avaliações

- GST Certificate - Pandurang SambhudasDocumento3 páginasGST Certificate - Pandurang SambhudasPandurang sambhudasAinda não há avaliações

- Statement of Account: Date Narration Chq./Ref - No. Value DT Withdrawal Amt. Deposit Amt. Closing BalanceDocumento2 páginasStatement of Account: Date Narration Chq./Ref - No. Value DT Withdrawal Amt. Deposit Amt. Closing Balancemozo dingdongAinda não há avaliações

- Step Transaction Acknowledgment: SuccessDocumento1 páginaStep Transaction Acknowledgment: Success@nshu_theachieverAinda não há avaliações

- HP PDFDocumento1 páginaHP PDFshekhar moreAinda não há avaliações

- Admit Card 2019-20 Odd-Sem PDFDocumento2 páginasAdmit Card 2019-20 Odd-Sem PDFRohit kumarAinda não há avaliações

- Statement of Account: State Bank of IndiaDocumento7 páginasStatement of Account: State Bank of IndiaPriyabrata MishraAinda não há avaliações

- Offer Letter Debojyoti MukherjeeDocumento6 páginasOffer Letter Debojyoti MukherjeeDebojyoti MukherjeeAinda não há avaliações

- Statement of Account: Date Narration Chq./Ref - No. Value DT Withdrawal Amt. Deposit Amt. Closing BalanceDocumento3 páginasStatement of Account: Date Narration Chq./Ref - No. Value DT Withdrawal Amt. Deposit Amt. Closing BalanceRajesh KumarAinda não há avaliações

- Shriram Life Insurance customer mandate formDocumento3 páginasShriram Life Insurance customer mandate formMOHD AFZAAinda não há avaliações

- Provident Fund Statement 2019-2020Documento1 páginaProvident Fund Statement 2019-2020VishwasKashyapAinda não há avaliações

- Aadhaar SURESH Original PDFDocumento1 páginaAadhaar SURESH Original PDFCA N RajeshAinda não há avaliações

- Fixed Term Contract OfferDocumento11 páginasFixed Term Contract OfferSrinivas KAinda não há avaliações

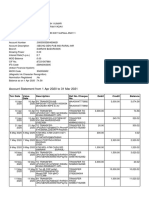

- Account Statement From 1 Apr 2020 To 31 Mar 2021: TXN Date Value Date Description Ref No./Cheque No. Debit Credit BalanceDocumento14 páginasAccount Statement From 1 Apr 2020 To 31 Mar 2021: TXN Date Value Date Description Ref No./Cheque No. Debit Credit BalanceMithilesh KumarAinda não há avaliações

- BANK StatementDocumento2 páginasBANK StatementSekhon VeerAinda não há avaliações

- Police Verification FormDocumento2 páginasPolice Verification Formrohit1409Ainda não há avaliações

- Appt of Biswajit Bhuiya PDFDocumento313 páginasAppt of Biswajit Bhuiya PDFsurajit maiti100% (1)

- Acct Statement - XX2139 - 02062022 PDFDocumento10 páginasAcct Statement - XX2139 - 02062022 PDFpooja mandalAinda não há avaliações

- Statement of Account: Date Narration Chq./Ref - No. Value DT Withdrawal Amt. Deposit Amt. Closing BalanceDocumento5 páginasStatement of Account: Date Narration Chq./Ref - No. Value DT Withdrawal Amt. Deposit Amt. Closing BalanceAmit GodaraAinda não há avaliações

- PrintApplication PDFDocumento1 páginaPrintApplication PDFRamakanta BiswalAinda não há avaliações

- HDFC Bank statement for Javed AliDocumento3 páginasHDFC Bank statement for Javed AliNew NewAinda não há avaliações

- EROsb FUiu DZP Z93 KDocumento12 páginasEROsb FUiu DZP Z93 KChandan GhoshAinda não há avaliações

- UntitledDocumento2 páginasUntitledVasant ChaudhariAinda não há avaliações

- PDFDocumento22 páginasPDFAnonymous ccPU4fAinda não há avaliações

- 1574317819091Documento17 páginas1574317819091JohnsonAinda não há avaliações

- KDXP ZBKKJ 7 Awt 49 yDocumento15 páginasKDXP ZBKKJ 7 Awt 49 yBharath AAinda não há avaliações

- Statement of Account: Date Narration Chq./Ref - No. Value DT Withdrawal Amt. Deposit Amt. Closing BalanceDocumento1 páginaStatement of Account: Date Narration Chq./Ref - No. Value DT Withdrawal Amt. Deposit Amt. Closing Balancesandip nagareAinda não há avaliações

- RAJEESH P N bank statement analysisDocumento3 páginasRAJEESH P N bank statement analysisGersome HenryAinda não há avaliações

- Canara - Epassbook - 2023-06-17 16:03:13.102279Documento3 páginasCanara - Epassbook - 2023-06-17 16:03:13.102279hamidanwarbelinjaAinda não há avaliações

- First Marraiage Certificate: Government of TelanganaDocumento1 páginaFirst Marraiage Certificate: Government of Telanganadeepu227Ainda não há avaliações

- StatementOfAccount 244682927 Dec10 173649Documento16 páginasStatementOfAccount 244682927 Dec10 173649vsguru15Ainda não há avaliações

- Account StatementDocumento10 páginasAccount StatementPuBg FreakAinda não há avaliações

- Electricity Bill - History PDFDocumento1 páginaElectricity Bill - History PDFR.GAinda não há avaliações

- Statement of Account: Date Narration Chq./Ref - No. Value DT Withdrawal Amt. Deposit Amt. Closing BalanceDocumento9 páginasStatement of Account: Date Narration Chq./Ref - No. Value DT Withdrawal Amt. Deposit Amt. Closing Balancevadivel ramalingamAinda não há avaliações

- Saket Kumar Primary Account Holder Name: Your A/C StatusDocumento14 páginasSaket Kumar Primary Account Holder Name: Your A/C StatusSaket KumarAinda não há avaliações

- UNSCW. United Nations Status On The Commission of WomenDocumento19 páginasUNSCW. United Nations Status On The Commission of WomenAbdul RehmanAinda não há avaliações

- Ron Alfred Moreno Victimology Module 10Documento2 páginasRon Alfred Moreno Victimology Module 10RON ALFRED MORENOAinda não há avaliações

- The City That Became Safe - New York's Lessons For Urban Crime and Its ControlDocumento272 páginasThe City That Became Safe - New York's Lessons For Urban Crime and Its ControlshmadmAinda não há avaliações

- Child Protection Policy SummaryDocumento10 páginasChild Protection Policy SummaryEdgar Senense CariagaAinda não há avaliações

- Death Penalty1Documento30 páginasDeath Penalty1Amreen SaifiAinda não há avaliações

- Collateral Damage: The Impact of Anti-Trafficking Measures On Human Rights Around The WorldDocumento277 páginasCollateral Damage: The Impact of Anti-Trafficking Measures On Human Rights Around The WorldGaatw SecretariatAinda não há avaliações

- Victimology Chapter 2Documento3 páginasVictimology Chapter 2seanleboeuf100% (1)

- GERONIMO DADO, Petitioner, vs. PEOPLE OF THE PHILIPPINES, RespondentDocumento8 páginasGERONIMO DADO, Petitioner, vs. PEOPLE OF THE PHILIPPINES, RespondentAmicus CuriaeAinda não há avaliações

- Criminal Justice SystemDocumento5 páginasCriminal Justice SystemMoshu TenseiAinda não há avaliações

- Sociological Perspectives of Indian SocietyDocumento64 páginasSociological Perspectives of Indian SocietyPranay BhardwajAinda não há avaliações

- ASCI, Hyd, Annual Rept 2006-07Documento60 páginasASCI, Hyd, Annual Rept 2006-07spsureshpillaiAinda não há avaliações

- Nunavunmi Maligaliuqtiit Nunavut Court of JusticeDocumento12 páginasNunavunmi Maligaliuqtiit Nunavut Court of JusticeNunatsiaqNewsAinda não há avaliações

- Human Trafficing 2 PDFDocumento39 páginasHuman Trafficing 2 PDFAnonymous lQ17JYTkhCAinda não há avaliações

- Human Trafficking SurveyDocumento28 páginasHuman Trafficking SurveyRonda HolmesAinda não há avaliações

- Criminal Law CasesDocumento197 páginasCriminal Law CasesKrissie GuevaraAinda não há avaliações

- White Collar CrimesDocumento13 páginasWhite Collar CrimesAkankshaAinda não há avaliações

- The Nature of Crimes.Documento2 páginasThe Nature of Crimes.maciucosulAinda não há avaliações

- Service Charter: For Victims of Crime in South AfricaDocumento8 páginasService Charter: For Victims of Crime in South AfricaLizbeth MafilaneAinda não há avaliações

- University students' views on revengeDocumento97 páginasUniversity students' views on revengeSAIKAT PAULAinda não há avaliações

- Ra 9262 (Vawc)Documento13 páginasRa 9262 (Vawc)Jose Li ToAinda não há avaliações

- Policy Brief on Human Trafficking FindingsDocumento8 páginasPolicy Brief on Human Trafficking Findingsalsan15Ainda não há avaliações

- Criminal Law and Procedure Chapter 10Documento3 páginasCriminal Law and Procedure Chapter 10Daniel LyndsAinda não há avaliações

- Family ResourcesDocumento33 páginasFamily ResourcesJackie S LaymanAinda não há avaliações

- Ricalde vs. People of The PhilippinesDocumento21 páginasRicalde vs. People of The PhilippinesAnonymous KaNu0py71Ainda não há avaliações

- UNIT III Ethics, Human ValuesDocumento27 páginasUNIT III Ethics, Human ValuesViswaprem CAAinda não há avaliações

- The Protection of Children From Sexual Offences ActDocumento1 páginaThe Protection of Children From Sexual Offences ActNeeraj BhargavAinda não há avaliações

- People v Rebucan: Murder CaseDocumento12 páginasPeople v Rebucan: Murder CaseMir SolaimanAinda não há avaliações

- Hga518 Essay e de JongDocumento17 páginasHga518 Essay e de Jongapi-325126195Ainda não há avaliações

- Dhurve CRPC NewDocumento29 páginasDhurve CRPC NewRohit Singh DhurveAinda não há avaliações

- Criminal Law 1 Case Digest | People v Germina | Mitigating CircumstancesDocumento2 páginasCriminal Law 1 Case Digest | People v Germina | Mitigating CircumstancesRubz JeanAinda não há avaliações

- Colorado Springs Police Department Annual Report 2014 PDFDocumento76 páginasColorado Springs Police Department Annual Report 2014 PDFMichael_Lee_RobertsAinda não há avaliações