Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

'In Eo Solo Dominivm Popvli Romani Est Vel Caesaris

Enviado por

hristijan_anchTítulo original

Direitos autorais

Formatos disponíveis

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

'In Eo Solo Dominivm Popvli Romani Est Vel Caesaris

Enviado por

hristijan_anchDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

'In eo Solo Dominivm Popvli Romani est vel Caesaris' Author(s): A. H. M.

Jones Source: The Journal of Roman Studies, Vol. 31 (1941), pp. 26-31 Published by: Society for the Promotion of Roman Studies Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/297101 Accessed: 03/02/2010 08:55

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at http://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=sprs. Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission. JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Society for the Promotion of Roman Studies is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The Journal of Roman Studies.

http://www.jstor.org

' IN EO SOLO DOMINIVM POPVLI ROMANI EST VEL CAESARIS'

By A. H. M. JONES

The doctrine that dominiumin provincial soil was vested in the Roman people or in Caesar has been taken far more seriously in modern, than it ever was in ancient, times. There is no evidence, as the late Professor Tenney Frank argued in volume xvii of this Journal, that the doctrine had any effect on the policy of the Roman government under the Republic or in the early years of the Principate. It may be added that there is equally little evidence that it was put to any practical use at any later period. At no time did the Roman government treat provincial landholders as tenants at will, or assume the right of arbitrarily dispossessing them: confiscation always remained a penal measure. Julius Frontinus,1 writing under Domitian, does, it is true, use the doctrine to explain why provincial landholders pay tribute: ' possidere enim illis quasi fructus tollendi causa et praestandi tributi condicione concessum est.' But it may be questioned how seriously Frontinus intended these words to be taken: the ' quasi' suggests that he is speaking figuratively. And in any case the theory had no effect on administrative practice. A tenant could be evicted for failing to pay his rent 2: a landowner who did not pay his tribute remained, despite the theory, liable only for the amount of his debt to the State.3 Even in the Byzantine period the distinction between private land and land belonging to the State, or rather to the emperor, remained perfectly unequivocal. If Justinian was conscious that the dominiumin provincial soil was vested in himself, he parted with his rights in a singularly light-hearted manner. So far as legal procedure went he assimilated Italian to provincial soil, abolishing such peculiarly Italian concepts as nudum ex iure 4 Quiritium dominium and usucapio by two years' possession, and applying to Italian soil the provincial rule of longi temporispraescriptio.5 The result of his reforms he nevertheless states is that 'his modis non solum in Italia sed in omni terra quae nostro imperio gubernatur dominium rerum, iusta causa possessionis praecedente, adquiratur .6 The italics are mine: Justinian lays no stress on the change, and it is only the commentatorTheophilus who at this point recalls the doctrine of Gaius, and underlines the emperor's beneficence in surrendering his rights.7

1 Bruns 7, ii, 86. 2 Gaius, Inst. iii, 145. 3 Dig. xlix, xiv, 45, ? I2. 4 Cod. Just. vii, xxv, I.

5 Ibid. vii, xxxi, i.

6

7 Comm. in Inst. ii, i, 40.

Just. Inst. ii, vi, pr.

'IN

EO SOLO DOMINIVM POPVLI ROMANI EST VEL CAESARIS' 27

The doctrine does not seem, in fact, to have interested constitutional lawyers. It is to explain problems of private law that it is invoked by Gaius. It is enunciated in so many words to account for the fact that solumItalicum,when a corpse was lawfully buried in it, became religiosum, whereas solumprovincialein similar circumstances became pro religioso only. The answer is that we make land religiosum ' mortuum inferentes in locum nostrum', and the land in the provinces is not ours.8 The doctrine also clearly in Gaius' mind underlies the other differences between Italian and provincial soil. The former is res mancipi, can be conveyed by mancipatioand in iure cessio,and is capable of usucapio. The latter is nec mancipi, can be conveyed by traditio only, and is Gaius' treatment of loca sacra and religiosa is not altogether satisfying. The distinction between the two is, he says, that land becomes sacer only by authority of the Roman People, whereas a private citizen can make his land religiosus.10 He goes on to explain why provincial land cannot become properly speaking religiosus. He then adds: ' item quod in provinciis non ex auctoritate populi Romanis consecratum est proprie sacrum non est '.1 Now we know from a letter of Trajan to Pliny 12 that provincial soil could not become sacer. It would appeartherefore that in this awkward sentence Gaius is shuffling. He knows that in the provinces the soil is incapable of becoming either religiosus or sacer. His theory accounts satisfactorily for the former fact. The latter is left unexplained and Gaius glosses over the difficulty by restating the unexceptionable principle that land can be rendered sacer only by authority of the Roman People and inconsequently Trajan not only states that provincial soil is incapable of being sacer, but gives an explanation which is more satisfying than that of Gaius : ' cum solum peregrinae civitatis capax non sit dedicationis quae fit nostro iure.' The explanation will cover

all the facts. Sacer, religiosus, res mancipi, mancipatio, in iure cessio fore applicable to ager Romanus only. Traditio, being iuris gentium, adding ' in provinciis '. incapable of usucapio.9

and usucapioare concepts and processes of the ius civile and there-

is applicable to all negotiable objects, including provincial soil. Trajan's viewpoint seems to be shared by Cicero. When Decianus entered in the Roman census estates that he had acquired at Apollonis, a free city of Asia, Cicero asked: ' sintne ista praediacensui censendo, habeant ius civile, sint necne sint mancipi, subsignari apud aerarium aut apud censorem possint ? ' 13 Most

8 10

Inst. ii, 9 Inst. ii, 7. I4a, 21, 27, 31, 46. Ibid. ii, 5, 6.

13

11 Ibid. ii, 7. 12 Pliny, Ep. x, 50. Cic., pro Flacco, 80.

28

A. H. M. JONES

of these questions would have to be answered in the negative if the land were, as in Gaius' theory, ager publicuspopuli Romani, but the second ' habeant ius civile' surely implies that Cicero regarded land in the territory of Apollonis as iuris peregrini. Trajan's theory is not only authoritativeas that of an emperor; it also seems to have the support of a great constitutional theorist of the Republic; and finally it explains the facts. I venture to suggest that it is correct. What then is the origin of Gaius' doctrine ? Since it was never taken up by the government, despite its obvious usefulness as a constitutional principle, but is known only as an explanation of problems of private law, it was in all probability evolved in order to explain such problems. It will therefore be useful to trace the development of Roman land law. Under Roman law agerprivatus could be conveyed either by the formal processes of mancipatioor in iure cessioor by the informal from process of traditio. The two former transferredthe dominium seller to buyer. The last transferredpossessioonly, but this flaw in the transaction was automatically remedied by the lapse of time, since possessioin good faith for two years conferred dominium by usucapio.14 These rules naturally applied to Roman citizens and (or peregrinipossessing commercium) to ager Romanus. Under the Republic it was apparently assumed that the territory of any community which accepted the Roman citizenship became part of the ager Romanus,and thus after the enfranchisement of the Italian allies the ager Romanusbecame to all intents and purposes coincident with Italy. Hence the concept of solum Italicum. Nevertheless there was ager Romanus outside Italy. Most of it was ager publicus,so that questions of conveyancing did not arise. But when the Roman People founded transmarine colonies, the parts of its ager publicus thus converted into ager privatus seem to have been regarded as possessing the same rights as Italian soil: at any rate the allotments at Carthage under the Lex Rubria do not appear, so far as can be judged from the fragmentary text of the Lex Agraria, to be differentiated from ager privatus in Italy.15 It seems to me probable that Caesar and Augustus continued to regard it as normal that Roman colonies planted in the provinces should form part of the ager Romanus. We know at any rate that a large number of their colonies possessed what Pliny and later authors call the ius Italicum,l6 whereby their soil had the same

Gaius, Inst. ii, 40-2. Bruns, 7, i, no. I I, 11.53 ff. ' 16 P-W s.v. 'Coloniae' Ius 580 f., Italicum' 1240. It must be remembered that our list of coloniae iuris Italici is far

15

14

from exhaustive, since it depends on such obiter dicta of the classicaljurists asJustinian's compilators have preserved and on the chance that a colony issued coins and used the Marsyas type on them.

'IN

EO SOLO DOMINIVM

POPVLI

ROMANI

EST VEL CAESARIS'

29

legal quality as that of Italy. Provincial municipiaseem, on the other hand, to have been treated differently: we know of very few which possessed the ius Italicum, and these are of late origin.17 The reason for this change of policy was probably fiscal. Ager Romanus was theoretically subject to the Roman tributum, but, as this was never levied, it was practically tax-free. This had not mattered so long as the communities enfranchised were Italian, since the Italian allies had never paid taxes to Rome. But when Caesar introduced the practice of granting the citizenship freely to provincial communities, the financial consequences would have been serious had their territoriesaccording to custom become ager Romanus. The same considerations of course applied to transmarine colonies, and ultimately led to the same change of policy, but at first their condition was not altered, partly perhaps because they were felt to be more intimately a part of the Roman State, partly because they consisted of men who were already Roman citizens, and most of them veterans, and who therefore had special claim to consideration, partly, no doubt, because they were relatively few in number. How the change in policy was affected we do not know, but the most plausible hypothesis is that a clause was inserted in the charters of newly created municipia,stating that the quality of the soil was unaffected by the enfranchisement of the community. If this was so a novel situation would have arisen. Hitherto individual Romans had bought and sold provincial land. What forms of law they used we do not know. It seems most probable that, as later in imperial Egypt,18they employed the legal procedure of the place, though they may have had recourse to traditio, which being iuris gentium was universally applicable. But now there were whole communities of Roman citizens, who could use no other law but Roman, buying and selling land which was not Roman. Traditio was the only procedure available to them. Lawyers would naturally have compared the processes applicable on Italian and on provincial soil. On provincial soil there was no mancipatioor in iure cessio, but only traditio. On Italian soil traditio was also common, perhaps indeed the normal procedure, but it conveyed possessio only: dominiumfollowed by usucapio. On provincial soil, the lawyers argued, traditio similarly transferredpossessio-but there was no usucapio. Where then had the dominiumvanished ?

17 Stobi (Dig. 1, xv, 8, ? 8) and Coela (Head, Hist. Num.2 p. 259, for a Marsyas statue) seem to be the only municipia possessing ius Italicum, and of these Stobi is not known to be earlier than Flavian and Coela

is Hadrianic. Nothing is known of the four Dalmatian communities stated to be iuris Italici in Pliny, HN iii, 139. 18 Mitteis, Grundziige, I72.

30

A. H. M. JONES

At this stage it will be profitable to examine with greater care the doctrine enunciated by Gaius. In the first place he states that the dominium in provincial soil 'populi Romani est aut Caesaris'. Caesar's appearance is unexpected and, on any sound constitutional doctrine, inexplicable. In the second place he divides provincial soil into two categories, praedia stipendiaria and tributaria, and explains that ' stipendiaria sunt ea quae in his provinciis sunt quae propriaepopuli Romani esse intelleguntur, tributariasunt ea quae in his provinciis sunt quae propriaeCaesaris esse creduntur '19 It would seem that in their search for a dominus of provincial land the lawyers seized on the phrases provinciae publicae and provinciae Caesaris and interpreted them as meaning owned by the Roman People and Caesar respectively. If provincial land was in reality solumperegrinarum civitatium the theory that ' in eo solo dominium populi Romani est vel and Caesaris' is a conveyancer's phantasy, Mommsen's view of the juristic status of the provinces must be abandoned. He held that provincial communities made or were deemed to have made a deditio on annexation, and that their juristic position remained unchanged thereafter. Thus the inhabitants of the provinces were in strict law dediticii, and their land ager publicuspopuli Romani. In a previous article in this Journal 20 I argued that the evidence does not seem to tally with Mommsen's view of the personal status of provincials, the majority of whom appear to have been not dediticii but peregrini, that is, members of civitates peregrinae. I suggested that, though a deditio was made or deemed to have been made on annexation, its effects were undone in so far as the lex provinciae reconstituted (or in some cases constituted) civitates. The members of these became peregrini, and their civitatium: territories, I would now add, became solumperegrinarum to quote Cicero 21: 'cum ... senatus et populus Romanus Thermitanis ... urbem agros legesque suas reddidisset.' I further suggested that where no civitates were constituted, as in Egypt, the inhabitants remained dediticii. It should follow that the land in such areas remained ager publicuspopuli Romani. This in Egypt was substantiallytrue, but on this point the Romans seem to have tempered legal logic with expediency. They kept the land of the conquered government, but allowed private landowners in most cases to retain their title. Nevertheless the principle that the land of a conquered people belonged to the Roman government unless and until a city was constituted on it would seem to have still prevailed in the Flavian period. Josephus 22

19 Inst. ii, 21.

20 21 22

Verr.

ii, 90.

JRS xxvi (1936), 223 ff., esp. 229-232.

Bell. Iud. vii, 216-17.

'IN

EO SOLO DOMINIVM POPVLI ROMANI EST VEL CAESARIS'

31

between the emperor and the Roman People, already at this period common in ordinary and especially provincial minds, these words seem to express correctly the official attitude to provincial soil.

o' sKE? 'louSaccov' yap KaTC-rKiEv T6oAXV, TtCcravxcbpacvarroSocOal TC-rOV i5iav EacuZr Tr Xcbpav uAarTTcov. If one allows for the confusion rv

says that on the conclusion of the Jewish war Vespasian ordered

Você também pode gostar

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)No EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Nota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (98)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeNo EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (5794)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingNo EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (400)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureNo EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryNo EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (231)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceNo EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (895)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnNo EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (234)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItNo EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (838)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerNo EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (271)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaNo EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (266)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaNo EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (45)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersNo EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (345)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyNo EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (2259)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreNo EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)No EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Nota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (121)

- Special Power of AttorneyDocumento6 páginasSpecial Power of AttorneyJem Mutiangpili MarquezAinda não há avaliações

- Proposal Submitted To HDFC ERGODocumento7 páginasProposal Submitted To HDFC ERGOTathagat JhaAinda não há avaliações

- Snell & Miller (1988) Emotional Self DiscloussereDocumento15 páginasSnell & Miller (1988) Emotional Self DiscloussereNoemí LeónAinda não há avaliações

- Christophe Bouton - Time and FreedomDocumento294 páginasChristophe Bouton - Time and FreedomMauro Franco100% (1)

- 4 - de La Torre v. CA, GR No. 160088 and GR No. 160565Documento1 página4 - de La Torre v. CA, GR No. 160088 and GR No. 160565Juvial Guevarra BostonAinda não há avaliações

- Kilayko V TengcoDocumento3 páginasKilayko V TengcoBeeya Echauz100% (2)

- TikTok Brochure 2020Documento16 páginasTikTok Brochure 2020Keren CherskyAinda não há avaliações

- EVIDENC1Documento83 páginasEVIDENC1mtabcaoAinda não há avaliações

- Standard 7 CC Workbook1Documento25 páginasStandard 7 CC Workbook1Donna Mar25% (4)

- In 1 Corinthians 13 LessonDocumento16 páginasIn 1 Corinthians 13 LessonMe-Anne Intia0% (1)

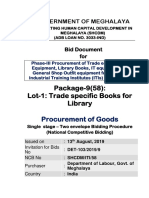

- BidDocument Phase 3 Package-9 (58) Lot-1 RebidDocumento150 páginasBidDocument Phase 3 Package-9 (58) Lot-1 RebidT TiwariAinda não há avaliações

- Guidelines For Students Association in Manonmaniam Sundaranar University DepartmentsDocumento2 páginasGuidelines For Students Association in Manonmaniam Sundaranar University DepartmentsDavid MillerAinda não há avaliações

- The Virtues of Al-Madeenah - Shaikh 'Abdul Muhsin Al-Abbad Al-BadrDocumento20 páginasThe Virtues of Al-Madeenah - Shaikh 'Abdul Muhsin Al-Abbad Al-BadrMountainofknowledgeAinda não há avaliações

- Self-Help Groups For Family Survivors of Suicide in JapanDocumento1 páginaSelf-Help Groups For Family Survivors of Suicide in JapanTomofumi OkaAinda não há avaliações

- Judgment of Chief Justice J.S. Khehar and Justices R.K. Agrawal, S. Abdul Nazeer and D.Y. ChandrachudDocumento265 páginasJudgment of Chief Justice J.S. Khehar and Justices R.K. Agrawal, S. Abdul Nazeer and D.Y. ChandrachudThe WireAinda não há avaliações

- Ethicsinscience FinalDocumento7 páginasEthicsinscience Finalapi-285072831Ainda não há avaliações

- 162 - Aguirre V FQBDocumento2 páginas162 - Aguirre V FQBColee StiflerAinda não há avaliações

- UNIT-III-LESSON-III-Teaching As A Vocation and MissionDocumento8 páginasUNIT-III-LESSON-III-Teaching As A Vocation and MissionFrancisJoseB.PiedadAinda não há avaliações

- International Commercial Agency Agreement Sample TemplateDocumento6 páginasInternational Commercial Agency Agreement Sample Templatemjavan255Ainda não há avaliações

- Lifespan Development: Why Is The Study of Lifespan Development Important?Documento23 páginasLifespan Development: Why Is The Study of Lifespan Development Important?mehnaazAinda não há avaliações

- Cultural Behaviour in Business: Addressing SomeoneDocumento2 páginasCultural Behaviour in Business: Addressing SomeoneEva Oktavia RamuliAinda não há avaliações

- Case Study: TEAM-2Documento5 páginasCase Study: TEAM-2APARNA SENTHILAinda não há avaliações

- Jsa CPBDocumento3 páginasJsa CPBmd maroofAinda não há avaliações

- Code of Business Conduct and EthicsDocumento2 páginasCode of Business Conduct and EthicsSam GitongaAinda não há avaliações

- 9 BoxDocumento10 páginas9 BoxclaudiuoctAinda não há avaliações

- AssignDocumento1 páginaAssignloric callosAinda não há avaliações

- Article 806 - Javellana Vs Ledesma DigestDocumento1 páginaArticle 806 - Javellana Vs Ledesma Digestangelsu04Ainda não há avaliações

- Manaloto Vs VelosoDocumento11 páginasManaloto Vs VelosocessyJDAinda não há avaliações

- PDFDocumento2 páginasPDFasadqureshi1510% (1)

- ZarathustraDocumento531 páginasZarathustraAnonymous DsugoSBa100% (1)