Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

Defendants' Motion For Summary Judgment

Enviado por

Michael_Lee_RobertsTítulo original

Direitos autorais

Formatos disponíveis

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Defendants' Motion For Summary Judgment

Enviado por

Michael_Lee_RobertsDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

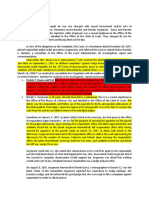

Case 1:11-cv-00645-RBJ-KMT Document 97 Filed 07/27/12 USDC Colorado Page 1 of 54

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE DISTRICT OF COLORADO Civil Action No. 11-cv-00645-RBJ-KMT ESTATE OF MARVIN L. BOOKER, REVEREND B.R. BOOKER, SR. and ROXEY A. WALTON, as Co-Personal Representatives, Plaintiffs, v. CITY AND COUNTY OF DENVER; DEPUTY FAUN GOMEZ, individually and in her official capacity; DEPUTY JAMES GRIMES, individually and in his official capacity; DEPUTY KYLE SHARP, individually and in his official capacity; DEPUTY KENNETH ROBINETTE, individually and in his official capacity; and SERGEANT CARRIE RODRIGUEZ, individually and in her official capacity; DENVER HEALTH AND HOSPITAL AUTHORITY d/b/a DENVER HEALTH MEDICAL CENTER, GAIL GEORGE, R.N., individually and in her official capacity, and SUSAN CRYER, R.N., individually and in her official capacity, Defendants.

DEFENDANTS COMBINED MOTION AND MEMORANDUM BRIEF IN SUPPORT OF MOTION FOR SUMMARY JUDGMENT ______________________________________________________________________________ Defendants, CITY AND COUNTY OF DENVER, FAUN GOMEZ, JAMES GRIMES, KYLE SHARP, KENNETH ROBINETTE and CARRIE RODRIGUEZ (collectively the Denver Defendants), by their attorneys, THOMAS S. RICE, SONJA S. McKENZIE, ERIC M. ZIPORIN, and SARAH E. McCUTCHEON of SENTER GOLDFARB & RICE, L.L.C., and pursuant to Fed.R.Civ.P. 56 and D.C.COLO.LCivR 56.1,

Case 1:11-cv-00645-RBJ-KMT Document 97 Filed 07/27/12 USDC Colorado Page 2 of 54

hereby submit their Combined Motion and Memorandum Brief in Support of Motion for Summary Judgment1 requesting the dismissal of all claims for relief as follows: I. INTRODUCTION

While many concerns exist for employees in jail, two things are paramount: security and order. Without these two, the safety of the deputies and others who work in the jail can be dangerously compromised, not to mention the safety of other inmates. Lacking security and order inside the jail can pose an even larger public safety risk to those outside of the facility. It is for these reasons that jail deputies receive extensive training on how to quell disturbances that threaten security and order, and to do so quickly, efficiently, and with certainty. There can be no margin for error as any breach to security and order can quickly escalate out of control. It is in this setting that Plaintiff has brought its claims against the Denver Defendants.2 Marvin Booker (Booker) was booked into the Downtown Detention Center on July 8, 2010, and a use of force incident occurred early the next day in response to Bookers unprovoked breach of security and order. Plaintiff claims that the deputies caused Bookers death and also allege that they failed to provide him timely medical care. And because Booker was AfricanAmerican, Plaintiff alleges that the deputies actions were motivated by his race and they conspired to use excessive force and ignore his medical needs. All of this malfeasance was allegedly done under the approving eye of the City and County of Denver, who Plaintiff alleges not only ratified the misconduct at issue, but encourages its deputies to use excessive force.

Pursuant to D.C.COLO.LCivR 56.1(A), the undisputed facts, argument, and recitation of legal authority are incorporated into this Motion for Summary Judgment in lieu of a separate opening brief. 2 While the caption appears to list Reverend B.R. Booker, Sr. and Roxey A. Walton as Plaintiffs (in their capacities as Co-Personal Representatives of the Estate), the only party which has standing is the Estate of Marvin L. Booker (Estate or Plaintiff). See Berry v. City of Muskogee, 900 F.2d 1489, 1506-1507 (10th Cir. 1990)(only remedy in 1983 death case is a survival action brought by the estate).

1

Case 1:11-cv-00645-RBJ-KMT Document 97 Filed 07/27/12 USDC Colorado Page 3 of 54

While the death of Booker is a tragedy, the inescapable truth is that none of this would have happened had he simply cooperated and did what he was told to do. Plaintiff alleges the following claims for relief against the Denver Defendants: First Claim for Relief: 42 U.S.C. 1983 Fourth Amendment excessive force; Second Claim for Relief: 42 U.S.C. 1983 Fourteenth Amendment

deprivation of life without due process; Third Claim for Relief 42 U.S.C. 1983 failure to provide medical care and treatment; Fourth Claim for Relief 42 U.S.C. 1983 failure to train or supervise against the City and County of Denver and Sergeant Carrie Rodriguez; Fifth Claim for Relief 42 U.S.C. 1985 conspiracy to interfere with civil rights; Sixth Claim for Relief 42 U.S.C. 1986 neglect to prevent conspiracy; and Tenth Claim for Relief Survival Action.3

Given the lack of evidence in the record to support these claims, as well as a lack of clearly established law to defeat the individual Defendants entitlement to qualified immunity, all claims against the Denver Defendants should be dismissed as a matter of law, including Plaintiffs claim for economic damages requesting recovery of social security benefits.

The Tenth Claim for Relief merely reasserts the Estates federal survival action as contemplated by Berry, supra, given that the Amended Complaint makes no reference to the Colorado survival statute (C.R.S. 13-20-101) and does not allege that the Court has supplemental jurisdiction over any state claim. The Tenth Claim for Relief is therefore duplicative of the other claims and does not entitle Plaintiff to any additional relief. That claim should therefore be dismissed.

Case 1:11-cv-00645-RBJ-KMT Document 97 Filed 07/27/12 USDC Colorado Page 4 of 54

II.

STATEMENT OF THE FACTS

A much different reality existed for Booker than the picture painted by Plaintiffs in their Amended Complaint. [Doc. No. 36.] Booker was born in 1954. In 1971, after a troubling childhood that led to an expulsion from school and multiple contacts with law enforcement, including time at a juvenile detention facility in Tennessee, Booker joined the Army. By 1974, he was serving a two year sentence in Leavenworth for armed robbery of military personnel and was later dishonorably discharged. Booker eventually made his way to Colorado, and was arrested in Denver during the 1980s and 1990s a total of 19 times, including arrests for disorderly conduct, trespass, loitering, escape, disturbing the peace, carrying a concealed weapon, and threatening assault. Booker was also arrested multiple times on various drug charges and admitted to using crack cocaine since the late 1980s. These arrests led to drug related charges and a felony conviction in Tennessee, as well as extensive periods of incarceration in Colorado. Records show that Booker displayed compulsive and irrational tendencies while in the Colorado Department of Corrections, to include assaultive behavior. While incarcerated in 1993, Bookers own writings gave insight into his troubled world, conceding that he was once a spiritual man but had forsaken his spirituality and no longer could discern between right and wrong. Booker spent considerable time both unemployed and as a homeless person. A friend reported that Booker was homeless in downtown Memphis in 2007 and 2008. He was homeless upon returning to Denver and spent some of his time prior to July of 2010 living in hotels or on the streets. Medically, Booker was diagnosed with depression, bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, and was suicidal. He had also been diagnosed with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease,

Case 1:11-cv-00645-RBJ-KMT Document 97 Filed 07/27/12 USDC Colorado Page 5 of 54

coronary artery disease, and congestive heart failure. And what was not discovered until his autopsy was that Booker had a heart twice the normal size for a man of his stature. Booker had been deemed disabled by the Social Security Administration as a result of these numerous maladies and was receiving Supplemental Security Income benefits. His autopsy showed the presence of cocaine in his system, consistent with a lengthy history of crack cocaine use. By the time Booker interacted with the subject deputies in July of 2010, he possessed most, if not all, of the classic symptoms for somebody at risk of sudden cardiac death. On the night of July 8, 2010, Booker was arrested by the Denver Police Department on a warrant for failing to appear at an earlier court appearance relating to a prior arrest for possession of drug paraphernalia. Police officers were called to the scene because a witness reported that Booker had been burning money, and thereafter determined that he had an active warrant. A witness at the scene and arresting officers described him as belligerent and very agitated. Booker was transported to the Downtown Detention Center (DDC) to be booked and processed into the jail. During the booking process, Booker became belligerent while deputies were attempting to fingerprint and photograph him. Booker again became belligerent and

uncooperative during his medical screening by shouting No before the nurse could complete a question. He was eventually placed in the cooperative seating area where he awaited

additional processing. This seating area is designed to permit inmates being processed to wait until called to various stations adjacent to the seating area to complete the booking process. The area is open and inmates are allowed to communicate with one another, watch television, and make telephone calls. Given the openness of the area, it is essential that inmates remain calm

Case 1:11-cv-00645-RBJ-KMT Document 97 Filed 07/27/12 USDC Colorado Page 6 of 54

and do not disrupt the deputies or other inmates to maintain security and order. In the event that an inmate is uncooperative, the inmate is moved to an isolation cell until the inmate is calm enough to complete the booking process. Until he was called up for additional processing, Booker mostly slept in the cooperative seating area. Defendant Faun Gomez (Gomez) eventually called Booker to her booking desk. Booker approached the desk, began yelling profanities, and making statements to the effect that he did not have to do what he was told. He was also upset that the deputy was going to take his money. Gomez told Booker to take a seat several times, but he refused and continued to yell. Given his lack of cooperation and disruptive behavior, based on her training, Gomez made the decision to place Booker in an isolation cell. She called several times for him to go to the cell, but Booker refused and ignored her commands. Booker initially started to walk toward Gomez, but then turned around and started walking back toward the stairs leading into the cooperative seating area, all the while yelling Fuck you and telling her he did not have to do as he was told. Gomez also heard Booker say something about his shoes. Gomez approached Booker with the intent of stopping him before he entered the cooperative seating area. She reached out to grab Bookers arm on two occasions, but both times he pulled away. Booker then raised his elbow and swung his arm backwards almost striking

Gomez in the head. The attempted assault was witnessed by other deputies in the area, to include Defendants Kenneth Robinette (Robinette), James Grimes (Grimes), Kyle Sharp (Sharp), and Carrie Rodriguez (Rodriguez). Aggression towards a deputy is one of the highest levels of threat in a jail setting. For this reason, Grimes, Robinette, and Sharp moved quickly to assist Gomez. After attempts at

Case 1:11-cv-00645-RBJ-KMT Document 97 Filed 07/27/12 USDC Colorado Page 7 of 54

moving him toward the isolation cell proved unsuccessful, the deputies wanted to get Booker down to the ground so that he could be more easily handcuffed and restrained. After the group fell into some surrounding chairs, the deputies were finally able to get Booker to the ground. Rodriguez also responded but the deputies were on the ground by the time she arrived. Once on the ground, the deputies needed to get Booker under control and restrained as quickly as possible. This need was magnified by the presence of numerous inmates in the cooperative seating area, and was consistent with their training as the fewer the deputies that get involved, the longer an incident can last and the potential need for greater force is increased. Normally an immediate show of force by multiple deputies will subdue an inmate without further incident, but this is not what happened with Booker. He continued to ignore commands and aggressively struggle with the officers. Since Booker had just attempted to assault Gomez and his attempt at controlling Booker was unsuccessful, Grimes attempted to control Booker in a carotid restraint.4 This restraint proved ineffective as Booker continued to resist and struggle. Hoping that the restraint would eventually work, Grimes attempted to continue the hold and would increase and decrease pressure roughly every 20 seconds. Robinette and Gomez struggled with Booker to get his hands and handcuff Booker as he continued to pull them away and ignore commands to give up his hands. In an attempt to achieve compliance with these commands, Sharp applied an Orcutt Police Nunchakus (OPN), a pain compliance tool, to Bookers ankle. Once Booker was finally handcuffed, Sharp released the pressure on the ankle and Booker immediately attempted to kick him. Sharp then reapplied

The hold is intended to cause unconsciousness by cutting off blood flow to the brain. The restraint does not inhibit the subjects ability to breathe as the crook of the elbow is outside the trachea while the bicep and forearm of the officer put pressure on the carotid arteries on either side of the neck.

Case 1:11-cv-00645-RBJ-KMT Document 97 Filed 07/27/12 USDC Colorado Page 8 of 54

the OPN and told the other deputies of the attempted kick. Given the kick and Bookers continued resistance, the decision was made to use a TASER in drive-stun mode as another pain compliance option. Rodriguez applied the TASER to Bookers thigh for 8 seconds. The deputies observed that Booker ceased resisting and struggling at that time, and Grimes released his hold. Once Booker was fully restrained and under control, the decision was made to place him in the isolation cell as was the original intent of Gomez. While carrying Booker to the cell, as well as while the deputies were inside the cell with him, the deputies noticed Booker making voluntary movements, and also noticed that he was breathing and making noises which gave them no cause for concern that Booker was in distress. But since a use of force incident had occurred, per procedure and their training, upon leaving the cell Rodriguez immediately went to get a nurse to evaluate Booker. Twenty-one seconds later, Sharp returned to the cell and noticed that Booker had not moved. He and Grimes immediately notified the nursing staff of the situation and informed them that they needed to hurry up. One nurse arrived followed by another nurse shortly thereafter and immediate attempts were made to resuscitate Booker. The Denver Fire Department arrived within minutes and took over the care. Paramedics were called and joined in the efforts to revive Booker. They eventually transported him to the Denver Health Medical Center where he was pronounced dead shortly after his arrival. The autopsy report provided diagnoses of cardiorespiratory arrest during physical restraint, hypertensive cardiovascular disease, emphysema, recent cocaine use, resuscitationrelated fractures of the sternum, and a listing of incidental findings. The cause of death was noted to be cardiorespiratory arrest during physical restraint. After the autopsy, the medical

Case 1:11-cv-00645-RBJ-KMT Document 97 Filed 07/27/12 USDC Colorado Page 9 of 54

examiner confirmed that Bookers own physical exertion, coupled with his medical conditions, can precipitate cardiac arrhythmia. III. STATEMENT OF UNDISPUTED MATERIAL FACTS

The following facts are established by the pleadings filed in this case, the discovery conducted, the videos of the incident5, and the affidavits submitted herewith. Although there are, of course, some factual disputes between the parties, the following material, dispositive facts are undisputed: 1. The intake area of the DDC is designed as a large open area with the center of that

area comprising the cooperative seating area which is surrounded by a railing and includes several rows of chairs and telephones. [Affidavit of Gary Wilson appended hereto as Exhibit A, 16; schematic of the floor plan appended hereto as Exhibit B.] 2. The intent of the department is to permit inmates who are being processed to wait

in the cooperative seating area until they are called to approach various stations to complete the booking process. Given the openness of the area, cooperation by inmates, meaning that they remain calm and do not disrupt the deputies or the other waiting inmates, is essential to maintaining order in the facility. [Exhibit A, 16.]

It is important to note that no single video or the totality of the videos can provide the entire perspective of what occurred during the roughly three minute use of force incident. The participants and the seating in the area obstruct the view at times. It is for this reason that the testimony of the officers becomes critical to fill-in that which cannot be seen on video. However, much as in Scott v. Harris, 550 U.S. 372 (2007), the videos serve as incontrovertible evidence of many material facts, namely that Booker disregarded orders to get in the isolation cell, that he pulled away from Gomez, that he swung his elbow in the direction of her head, that his hands could not be immediately secured on the ground, and that Booker was moving around on the floor as evidenced by the sudden jerking of the bodies of the deputies. The videos also show that the deputies did not strike or beat Booker with weapons, but calmly and with purpose employed control holds and pain compliance techniques to restrain him. (Proper foundation for the Courts consideration of the videos is provided in the Affidavit of Gary Wilson, Exhibit A, at 17.)

Case 1:11-cv-00645-RBJ-KMT Document 97 Filed 07/27/12 USDC Colorado Page 10 of 54

3.

If an inmate is uncooperative or disruptive, the inmate is moved to an

intake/isolation cell until the inmate is calm enough to complete the booking process. [Exhibit A, 16.] 4. There are several intake/isolation cells adjacent to the cooperative seating area,

and located on that same floor is a booking desk, the sergeants office, and the nurses station/office. [Exhibit A, 16; Exhibit B.] 5. Booker was arrested on July 8, 2010 pursuant to an arrest warrant ordered as a

result of his failure to appear at a hearing stemming from an arrest for possession of drug paraphernalia. [Certified copy of Case Information for Case Number 10GS188777 and Denver Police Department Warrant Arrest Report appended hereto as Exhibit C.] 6. At approximately 3:30 a.m. on July 9, 2010, after completing some preliminary

booking matters, Gomez called out Bookers name indicating that he needed to approach the booking desk. [Affidavit of Faun Gomez appended hereto as Exhibit D, 3-5.] 7. Booker rose from the cooperative seating area and approached Gomez yelling

profanities, moving his arms, and making statements to the effect of I dont have to do what you tell me and Youre going to take my fucking money. [Exhibit D, 6-7; DVD of videos appended hereto as Exhibit E, 3rd angle video at 3:34:25-3:34:526.] 8. On at least three occasions, Booker ignored directives from Gomez to sit, and

instead continued to yell, gesture with his hands, and make statements that he did not have to do as he was told. [Exhibit D, 6-9. Exhibit E, 3rd angle video at 3:34:40-3:34:52]

The video is not provided to the Court as evidence of the statements made by Booker and his refusal to sit down as directed. It is merely cited to in this paragraph, as well as paragraph 8 in this section, to provide the Court with a visual perspective of these events.

10

Case 1:11-cv-00645-RBJ-KMT Document 97 Filed 07/27/12 USDC Colorado Page 11 of 54

9.

Because of Bookers disruptive behavior, his refusal to follow directives, as well

as his level of agitation, pursuant to DDC procedure, Gomez decided that Booker needed to be placed in an isolation cell (I-8) until he calmed down. [Exhibit D, 10-11; Exhibit A, 16.] 10. Gomez walked toward I-8 and instructed Booker several times to come to the cell,

even unlocking the door and gesturing to get inside. Booker initially walked toward Gomez and then turned away and walked toward the stairs descending into the cooperative seating area. [Exhibit D, 12, 14-15; Exhibit E, 2nd angle video at 3:34:55- 3:35:06; Exhibit E, I-8 video at 3:34:57-3:35:03.] 11. As Booker walked away, he continued to yell statements to the effect of Fuck

you and I dont have to do what you tell me while moving his arms around and gesturing with his hands. [Exhibit D, 16; Exhibit E, 2nd angle video at 3:34:55-3:35:06.] 12. With the intent of stopping Booker before he entered the cooperative seating area

(which is the most dangerous area to make physical contact with an inmate given the number of other, unrestrained inmates), Gomez reached her hand toward Bookers upper left arm from behind, but Booker pulled away. Gomez tried again to grab Booker, but he swung his left arm up and away from her, again prohibiting Gomez from making contact with his arm. [Exhibit D, 17-20; Exhibit E, 2nd angle video at 3:35:06-3:35:09.] 13. Booker then turned and faced toward Gomez, grabbed the railing of the stairs with

his right hand, and then raised his left elbow and swung his arm up and backwards in the direction of Gomez, almost striking her. [Exhibit D, 21-22; Exhibit E, 2nd angle and Faun Gomez videos at 3:35:09-3:35:13.]

11

Case 1:11-cv-00645-RBJ-KMT Document 97 Filed 07/27/12 USDC Colorado Page 12 of 54

14.

Grimes, Robinette, Sharp, and Rodriguez all witnessed Booker swinging his

arm/elbow toward Gomez which they perceived as an act of aggression or an attempt to assault her. [Affidavit of James Grimes appended hereto as Exhibit F, 7-8; Affidavit of Kenneth Robinette appended hereto as Exhibit G, 8; Affidavit of Kyle Sharp appended hereto Exhibit H, 6-7; Affidavit of Carrie Rodriguez appended hereto as Exhibit I, 8.] 15. Grimes, Robinette, and Sharp immediately responded to Gomez location and

attempted to gain control of Booker to prevent him from moving further into the cooperative seating area and get him toward the isolation cell. Booker resisted and struggled with the deputies as he attempted to free himself while ignoring verbal commands to stop resisting, come with them to the isolation cell, and to provide his hands. [Exhibit D, 24-28; Exhibit F, 812; Exhibit G, 11-12; Exhibit H, 8-9; Exhibit E, Booker video at 3:35:13 3:35:25.] 16. Per their training, the intent of the deputies changed to get Booker to the floor so

they could better control him and get him in restraints, including handcuffing him. [Exhibit F, 12; Deposition testimony of Sheldon Marr7 appended hereto as Exhibit J, 88:16-25.] 17. The deputies and Booker fell to the floor where Booker continued to resist by

pushing, pulling, and moving his arms and legs which prevented the deputies from handcuffing him. Deputies continued to give commands to Stop resisting and Give me your hands. [Exhibit F, 13-14; Exhibit G, 13-17; Exhibit H, 12, 14; Exhibit I, 10-12; Exhibit E, Booker video at 3:35:25-3:35:55] 18. Because multiple deputies were involved in physical contact with an inmate who

had attempted to assault a deputy and Rodriguez was an on-duty supervisor, she remained

Deputy Marr was designated by DSD under Rule 30(b)(6) to testify as to arrest control and carotid restraint techniques and training.

7

12

Case 1:11-cv-00645-RBJ-KMT Document 97 Filed 07/27/12 USDC Colorado Page 13 of 54

standing near Booker so she could monitor the situation, and give instruction and assistance if needed. [Exhibit I, 10.] 19. After unsuccessfully attempting to gain control of Bookers arms, Grimes

attempted to place Booker in a carotid restraint. Grimes intent was to use the restraint to control Bookers movements to the point where he would voluntarily stop resisting or to render him temporarily unconscious so that he would stop moving around, and he was going to immediately release the restraint if Booker ceased actively resisting the deputies. [Exhibit F, 15-16; Exhibit E, James Grimes video at 3:35:26- 3:35:35.] 20. In attempting to place Booker in the carotid restraint, Grimes used his right arm

and placed pressure on both sides of Bookers neck, but avoided placing pressure on Bookers windpipe. Grimes placed the crook of his right arm in front of Bookers windpipe (with his elbow pointing away from Booker) with his right bicep and forearm applying pressure on either side of Bookers neck, using his left arm to pull his right hand towards his own body. Grimes upper body was positioned against Bookers left side, at his shoulder area, and his torso and legs were positioned against the floor. [Exhibit F, 16; diagram of carotid restraint appended hereto as Exhibit K; Exhibit E, James Grimes video at 3:35:31-3:35:45] 21. Booker continued to struggle against Grimes and his continued movement

prevented Grimes from completing the carotid restraint as evidenced by the fact that Booker continued to yell profanities, spit while he was doing so, and continued flailing around and struggling with the deputies.8 [Exhibit F, 17-18.]

An effective carotid restraint typically results in the subject going unconscious within 5-20 seconds. [Exhibit J, 61:10-62:1.]

13

Case 1:11-cv-00645-RBJ-KMT Document 97 Filed 07/27/12 USDC Colorado Page 14 of 54

22.

Grimes increased and decreased the amount of pressure applied to Bookers neck

as he attempted to apply the carotid restraint. Each time he lessened the pressure, Booker became more combative in his struggle, resulting in Grimes increasing the pressure. Grimes continued his attempts because the other deputies informed him that they were unable to get Booker in handcuffs and under control, in addition to himself feeling Booker moving around. [Exhibit F, 20-21; Exhibit E, James Grimes video at 3:35:45-3:38:02.] 23. Robinette and Gomez both attempted to secure Bookers hands so that he could

be handcuffed while giving him instructions to stop resisting and provide his hands. Booker resisted and continuously pulled his arms and hands away from the deputies, and trapped his left arm underneath his own body despite instructions to remove it. [Exhibit D, 34-37; Exhibit G, 16-17; Exhibit E, Kenneth Robinette video at 3:35:31-3:36:47; Exhibit E, Faun Gomez video at 3:35:50-3:36:47.] 24. Robinette was able to get Bookers right hand and applied a gooseneck control

hold with the intent that the hold would serve as a pain compliance technique to bring Bookers right arm behind his back enabling them to handcuff the right wrist. The hold was successful as Gomez was then able to handcuff Bookers right wrist. [Exhibit G, 18-20.] 25. Robinette and Gomez then focused on getting the left hand so that it could be

handcuffed. Booker held his left arm underneath his body and resisted the deputies attempts to free his left arm, while also pulling his handcuffed right arm away from Gomez. Despite Booker flailing and moving around, they were eventually able to roll Booker from side to side and retrieve the left hand which was then handcuffed. [Exhibit D, 40-44; Exhibit G, 21.]

14

Case 1:11-cv-00645-RBJ-KMT Document 97 Filed 07/27/12 USDC Colorado Page 15 of 54

26.

While Booker and the deputies were still standing, Sharp attempted to apply his

OPN to Bookers wrist to assist the other deputies in getting Booker to the ground and to get him to comply with commands, but was unable to do so because Booker was moving his arm and hand around too much. [Exhibit H, 10-11.] 27. The OPN is a control device that can be used to apply pressure or can be applied

in a twisting motion that can cause pain, resulting in pain compliance. [Exhibit H, 10.] 28. When Booker was on the ground, and after giving repeated commands to Stop

resisting, Sharp secured his OPN to Bookers left ankle and applied pressure without using the device in a twisting manner. Per his training, Sharps intent was to stop Booker from kicking and flailing his legs around and to gain compliance with verbal commands. [Exhibit H, 1215; Exhibit E, Kyle Sharp video at 3:35:28-3:35:35.] 29. Even after Sharp applied the OPN, he observed that Booker continued to move

around on the ground, including pulling his arms away from the deputies and preventing them from handcuffing him. Sharp heard other deputies making statements to the effect that they did not have his hands. [Exhibit H, 16-17; Exhibit E, Kyle Sharp video at 3:35:35-3:36:11.] 30. Once Sharp saw that Booker was in handcuffs, he started to remove the OPN

from Bookers left ankle. Almost immediately after releasing the pressure, Booker kicked his feet in Sharps direction. While Booker did not make contact, Sharp was concerned that Booker would continue to kick and injure him or another deputy, so he reapplied the OPN to Bookers left ankle and announced to the other deputies that Booker had tried to kick him. [Exhibit H, 20-21; Exhibit D, 48; Exhibit E, Kyle Sharp video at 3:36:50-3:36:57.]

15

Case 1:11-cv-00645-RBJ-KMT Document 97 Filed 07/27/12 USDC Colorado Page 16 of 54

31.

Grimes eventually requested a TASER given that the restraint he was using on

Booker was ineffective since Booker was continuing to be resistive and moving around. Grimes was also becoming fatigued and was concerned that he would be unable to maintain his hold on Booker and he would free himself and present a greater risk to the deputies and inmates in the area. [Exhibit F, 24.] 32. A TASER was given to Rodriguez and she informed Booker that she had a

TASER and that he needed to stop resisting and comply with the deputies. Booker continued to move his legs and struggle, and given that Grimes was also indicating that Booker was resisting, Rodriguez applied the TASER in drive stun mode to Bookers leg for several seconds. [Exhibit I, 19-24; Exhibit E, Carrie Rodriguez video at 3:37:21-3:37:559.] 33. Given that the TASER did not seem to have any effect on Booker, Rodriguez

removed the TASER from Bookers leg after several seconds. [Exhibit I, 25.] 34. Some deputies observed that Booker essentially stopped resisting and became

compliant after the use of the TASER. [Exhibit F, 28; Exhibit H, 23.] 35. Some deputies observed that Booker continued to move after the use of the

TASER. [Exhibit D, 56; Exhibit G, 27; Exhibit I, 25.] 36. After the use of the TASER, Sharp observed that Booker stopped pulling his arms

away from the deputies and stopped kicking and trying to stand up, so he removed the OPN from Bookers left ankle. [Exhibit H, 23.]

While the video appears to show that Rodriguez placed the TASER on Booker for roughly 28 seconds, a download from the TASER device confirms that it was applied to Booker for 8 seconds. (Unrelated downloads from different dates have been redacted.) [TASER download appended hereto as Exhibit L; proper foundation for the Courts consideration of the download is provided in Exhibit A, 18.]

16

Case 1:11-cv-00645-RBJ-KMT Document 97 Filed 07/27/12 USDC Colorado Page 17 of 54

37.

Once Grimes perceived that Booker had stopped resisting after the TASER was

used, Grimes released Booker and began to stand up roughly 5 seconds after Rodriguez removed the TASER from Booker. [Exhibit E, James Grimes video at 3:37:55-3:38:00; Exhibit F, 28.] 38. Gomez, Robinette, Sharp, and Rodriguez did not know that Grimes was

attempting a carotid restraint given the fact that his body was blocking their view. [Exhibit D, 39; Exhibit G, 23; Exhibit H, 19; Exhibit I, 18, 23.] 39. The entire use of force incident (from the time Gomez first made contact with

Bookers arm until Grimes released Booker) lasted for 2 minutes and 55 seconds. [Exhibit E, 2nd angle video at 3:35:07-3:38:02.] 40. According to their training and experience, the deputies observed that Booker was

incredibly strong, especially for someone of his size, and that the struggle with him lasted unusually long given his strength. [Exhibit D, 37; Exhibit F, 22.] 41. After the use of force incident, and prior to being carried to I-8, the deputies

observed actions by Booker which led them to believe that he was conscious and breathing. [Exhibit D, 56; Exhibit F, 28; Exhibit G, 29; Exhibit I, 26.] 42. While Booker was carried to I-8, the deputies observed actions by Booker and

heard noises from him which led them to believe that he was conscious. [Exhibit D, 59; Exhibit F, 31; Exhibit I, 30.] 43. The elapsed time between the end of the use of force incident and Booker being

placed in I-8 was 1 minute and 37 seconds. [Exhibit E, 2nd angle video at 3:38:02-3:39:39.]

17

Case 1:11-cv-00645-RBJ-KMT Document 97 Filed 07/27/12 USDC Colorado Page 18 of 54

44.

While inside I-8, the deputies witnessed voluntary movement from Booker as well

as the fact that he was breathing. [Exhibit D, 60-62, 64-66; Exhibit I, 36.] 45. The elapsed time between the deputies placing Booker in I-8 and leaving the cell

was 1 minute and 29 seconds. [Exhibit E, I-8 video at 3:39:39- 3:41:08.] 46. After leaving the cell, Rodriguez walked toward the nurses office per procedure

so that Booker could be evaluated following the use of force incident. Rodriguez advised the nurse that Booker needed to be evaluated and the nurse agreed to check on him. [Exhibit I, 39-43; Exhibit J, 117:21-118:3.] 47. Sharp returned to the cell 21 seconds later and called out to Grimes to take a look

at Booker since he had not moved since they left the cell. [Exhibit H, 28-30; Exhibit E, I8 video at 3:41:08 3:41:29.] 48. Grimes looked through the window and determined that Booker did not appear to

be breathing, so he shouted that he did not think Booker was breathing and he needed a nurse and a sergeant. [Exhibit F, 36-38.] 49. Sharp made his way to the nurses station and saw Rodriguez and called out to the

station that they needed to Step it up. Sharp made the same comment once he got to the nurses station. [Exhibit H, 32-33] 50. The elapsed time between Sharp returning to I-8 after Booker had first been

placed in the cell and a nurse arriving at the cell was 1 minute and 31 seconds. [Exhibit E, I-8 video at 3:41:29 3:43:00.]

18

Case 1:11-cv-00645-RBJ-KMT Document 97 Filed 07/27/12 USDC Colorado Page 19 of 54

51.

The total elapsed time between the completion of the use of force incident and a

nurse arriving at I-8 was 4 minutes and 58 seconds (from 3:38:02 3:43:00). [See above 43, 45, 47, 50.] 52. Other than Gomez who recognized Booker as someone who had been in the DDC

before, none of the other deputies recognized or knew Booker as of the date of the incident. [Exhibit D, 3; Exhibit F, 4; Exhibit G, 5; Exhibit H, 5; Exhibit I, 5.] 53. From 2005 until the date of the Booker incident, the DSD meted out the following (1) a written reprimand; (2) a

discipline to deputies for violations of its use of force policy:

suspension of 5 days; (3) a suspension of 27 days; (4) a suspension of 30 days; (5) a suspension of 60 days; and (6) four terminations (although one was reduced to a 120 day suspension). In addition, two deputies were disciplined in 2005 for violating the use of force policy but resigned before their pre-disciplinary meetings. [Exhibit A, 19-20.] 54. As a pre-condition of employment, each deputy sheriff employed by the DSD

must attend and successfully complete the DSD Training Academy. Training at the academy typically includes but is not limited to: use of force, arrest control and defensive tactics (to include the use gooseneck hold, the OPN, and the carotid restraint), TASER usage and certification, inmates constitutional rights, first aid/CPR, and Colorado statutes relating to the use of force. [Exhibit A, 3-4.] 55. DSD provides annual in-service training to its deputies which includes up to 40

hours of training on various topics, including but not limited to: use of force, arrest control and defensive tactics (including control holds and the carotid restraint), certification/recertification

19

Case 1:11-cv-00645-RBJ-KMT Document 97 Filed 07/27/12 USDC Colorado Page 20 of 54

on the TASER and OPN, inmates constitutional rights, first aid/CPR, and statutes relating to the use of force. [Exhibit A, 6-7.] 56. In addition to her Academy Training in 2004, Gomez received training on arrest

control and defensive tactics as well as on first aid/CPR during in-service trainings in 2005, 2006, 2007 and 2008. [Exhibit A, 9-11.] 57. In addition to his Academy Training in 1999, Grimes received training on arrest

control and defensive tactics and first aid/CPR during various in-service trainings from 2001 thru 2008. He also received training on the carotid restraint during those years either by way of an inservice training or as a member of the Emergency Response Unit. [Exhibit A, 9-10, 12.] 58. During his Academy Training in 2008, Sharp received training on arrest control

and defensive tactics, first aid/CPR, and the use of the OPN. [Exhibit A, 9-10, 13.] 59. During his Academy Training in 2007, Robinette received training on arrest

control and defensive tactics as well as first aid/CPR. [Exhibit A, 9-10, 14.] 60. In addition to her Academy Training in 1999, Rodriguez received use of force

training in 2000 and 2002. She attended in-service trainings in 2004, 2005, 2006, 2007, 2008, and 2009, which included use of force training. The 2004 training included certification on the TASER, and she was recertified on the device in 2006. Rodriguez received training on first aid/CPR in the Academy and again in 2004, and also received training in 2005 on referral of inmates for medical services. [Exhibit A, 9-10, 15.] 61. 24:13-18.] At a minimum, deputies are recertified in CPR every other year. [Exhibit J,

20

Case 1:11-cv-00645-RBJ-KMT Document 97 Filed 07/27/12 USDC Colorado Page 21 of 54

62.

Under the DSD policy, the carotid restraint, the TASER, the OPN, and

compliance techniques are all non-deadly force options. [Exhibit J, 84:13-85:18; 89:12-90:4] 63. Deputies receive training that the carotid restraint can be used in situations where

violent resistance is encountered, and can also be used where death or serious bodily harm will result to the officer. [Exhibit J, 89:12-24.] 64. Deputies receive training that there is a risk of brain damage to an inmate if the

carotid restraint is applied for more than a minute. [Exhibit J, 65:4-15.] 65. Deputies receive training that the carotid restraint should not be applied again to a

conscious inmate if the restraint has already rendered the inmate unconscious from a prior application. [Exhibit J, 127:6-19.] 66. Deputies receive training that if an inmate is known to have gone unconscious

from the use of the carotid restraint, deputies are to ensure that the inmates breathing is not restricted and to put the inmate on his side. [Exhibit J, 112:23-113:20.] 67. Deputies receive training on seven steps that must be followed if the inmate goes

unconscious following the use of the carotid restraint, to include placing the inmate on his side and checking vital signs (including a pulse) [Exhibit J, 113:21-114:25.] IV. STANDARD OF REVIEW

Summary judgment should be granted where, taking the facts in the light most favorable to the non-moving party, there is no genuine issue of material fact, and the moving party is entitled to judgment as a matter of law. See Deepwater Inv., Ltd. v. Jackson Hole Ski Corp., 938 F.2d 1105, 1110-11 (10th Cir. 1991). Summary judgment is appropriate if the pleadings, depositions, answers to interrogatories, and admissions on file, together with affidavits, if any, show

21

Case 1:11-cv-00645-RBJ-KMT Document 97 Filed 07/27/12 USDC Colorado Page 22 of 54

that there is no genuine issue as to any material fact and that the moving party is entitled to judgment as a matter of law. See Fed.R.Civ.P. 56(c). The existence of some alleged factual dispute is insufficient to defeat a supported motion for summary judgment. Anderson v. Liberty Lobby, Inc., 477 U.S. 242, 247-48 (1985). The opposing party must demonstrate a dispute over a material fact which affects the outcome of the case under the substantive law. Anderson, 477 U.S. at 248. V. A. ARGUMENT

QUALIFIED IMMUNITY AND PLAINTIFFS BURDEN.

Unlike other motions for summary judgment where the moving party carries the burden of proof to demonstrate that there is no genuine issue of material fact, when a defendant has asserted the affirmative defense of qualified immunity the burden then shifts to the plaintiff. Medina v. Cram, 252 F.3d 1124, 1128 (10th Cir. 2001) (citing Nelson v. McMullen, 207 F.3d 1202, 1205-206 (10th Cir. 2000)). In particular, a plaintiff must demonstrate the following elements by a preponderance of the evidence: (1) defendants actions violated a constitutional right; and (2) the right allegedly violated was clearly established at the time of the conduct at issue such that a reasonable law enforcement officer would have known that his challenged conduct was illegal. 10 Martinez v. Carr, 479 F.3d 1292, 1295 (10th Cir. 2007). The record must clearly demonstrate that Plaintiff has satisfied its heavy two-part burden; otherwise, the individual Defendants are entitled to qualified immunity. Gross v. Pirtle, 245 F.3d 1151, 1156 (10th Cir. 2001).

10

The United States Supreme Court has determined that the order in which a court addresses the two-step analysis is not mandatory. Pearson v. Callahan, 129 S.Ct. 808, 818 (2009).

22

Case 1:11-cv-00645-RBJ-KMT Document 97 Filed 07/27/12 USDC Colorado Page 23 of 54

Plaintiff does not meet this burden by identifying a right in the abstract and claiming the individual Defendants violated this right. Pueblo Neighborhood Health Ctrs., Inc. v.

Losavio, 847 F.2d 642, 645 (10th Cir. 1988). Rather, Plaintiff must articulate the clearly established constitutional right at issue and the conduct of the officers which violated the right with specificity, and demonstrate a substantial correspondence between the conduct in question and the prior law establishing that the actions of the individual Defendants were clearly prohibited. See Romero v. Fay, 45 F.3d 1472, 1475 (10th Cir. 1995). The relevant, dispositive inquiry in determining whether a right is clearly established is whether it would be clear to a reasonable officer that his conduct was unlawful given the situation with which he was confronted. Saucier v. Katz, 533 U.S. 199, 202 (2001). The law is clearly established when a United States Supreme Court or Tenth Circuit decision is on point, or if the clearly established weight of authority from other jurisdictions shows that the right must be as Plaintiff maintains. Roska v. Peterson, 328 F.3d 1230, 1248 (10th Cir. 2003)(internal citations omitted). In

analyzing this issue, the Tenth Circuit has concluded, in determining whether a right is clearly established, the courts assess the objective legal reasonableness of the action at the time of the alleged violation and ask whether the right was sufficiently clear that a reasonable officer would understand that what he was doing violated that right. Medina, 252 F.3d at 1128 (citing Wilson v. Layne, 526 U.S. 603, 615 (1999)). Applying these standards, the individual Defendants are entitled to qualified immunity on Plaintiffs claims under 1983 and 1985. Plaintiff cannot prove a constitutional violation, nor can it demonstrate that the clearly established law put the officers on notice that the force each

23

Case 1:11-cv-00645-RBJ-KMT Document 97 Filed 07/27/12 USDC Colorado Page 24 of 54

used under these circumstances was excessive or that their requests for medical assistance were so untimely as to violate the due process clause. B. THE INDIVIDUAL DEFENDANTS ARE ENTITLED TO QUALIFIED IMMUNITY ON THE USE OF FORCE CLAIM. 1. Plaintiffs claims must be analyzed exclusively under the due process clause.

Plaintiffs First Claim for Relief alleges excessive force in violation of the Fourth Amendment. However, given that Booker was a pretrial detainee at the time of the use of force incident, Plaintiff cannot bring a Fourth Amendment claim as the due process clause provides their only potential relief. Claims of excessive force are not governed by a uniform constitutional standard. Graham v. Connor, 490 U.S. 386, 393-394 (1989). Excessive force claims can be maintained under the Fourth, Fifth, Eighth, or Fourteenth Amendmentall depending on where the defendant finds himself in the criminal justice systemand each carries with it a very different legal test. Porro v. Barnes, 624 F.3d 1322, 1325 (10th Cir. 2010). The Tenth Circuit has held that the Fourth Amendment protects against unreasonable seizures in the context of the events leading up to and including an arrest, while the Eighth Amendment governs claims of excessive force involving a convicted inmate. Porro, 624 F.3d at 1325-26. And when neither the Fourth nor Eighth Amendment applieswhen the plaintiff finds himself in the criminal justice system somewhere between the two stools of an initial seizure and post-conviction punishmentwe turn to the due process clauses of the Fifth or Fourteenth Amendment and their protection against arbitrary governmental action by federal or state authorities. Id. at 1326 (referring to County of Sacramento v. Lewis, 523 U.S. 833, 843, 118

24

Case 1:11-cv-00645-RBJ-KMT Document 97 Filed 07/27/12 USDC Colorado Page 25 of 54

S.Ct. 1708, 140 L.Ed.2d 1043 (1998)). Detainees in this middle ground have been classified as pretrial detainees, a term defined by the Supreme Court as a person who has had a judicial determination of probable cause as a prerequisite to [the] extended restraint of [his] liberty following arrest. Bell v. Wolfish, 442 U.S. 520, 536 (1979)(quoting Gerstein v. Pugh, 42 U.S. 103 (1975)). It is well settled that claims of excessive force brought by a pretrial detainee are governed by the due process clause as opposed to the Fourth Amendment. See Graham, 490 U.S. at 395, n. 10; Porro, 624 F.3d at 1326; Meade v. Grubbs, 841 F.2d 1512, 1527 (10th Cir. 1988). Here, Booker was a pretrial detainee at the time of the incident as it is undisputed that he was arrested pursuant to a warrant, and thus a judicial determination of probable cause for his arrest had already occurred. [Statement of Undisputed Material Facts (SUMF), 5.] The initial

seizure or arrest had long since passed as Booker had been booked and detained in jail at the time the force was used. Importantly, Plaintiff does not dispute that Booker was lawfully arrested and detained, it simply challenge the conduct of the deputies after his arrest and during his detention at the jail. Accordingly, Plaintiffs claim of excessive force must be analyzed exclusively under the due process clause, and its First Claim for Relief alleging a Fourth Amendment violation must be dismissed as a matter of law.11 2. Use of force claims and the due process clause.

Plaintiffs Second Claim for Relief alleges a deprivation of life in violation of the due process clause. The allegation is based on the force that was used by the deputies against

11

The Tenth Circuit has held that the Fourth Amendment applies to claims of excessive force that arise after a warrantless arrest but before a probable cause hearing or arraignment. Austin v. Hamilton, 945 F.2d 1155, 1160 (10th Cir. 1991)(emphasis added). But again, here, Bookers arrest was made after a probable cause determination based on a warrant for his arrest.

25

Case 1:11-cv-00645-RBJ-KMT Document 97 Filed 07/27/12 USDC Colorado Page 26 of 54

Booker, as well as an allegation that the City encourages, condones, tolerates, and ratifies the use of excessive force. [Amended Complaint, Doc. No. 36, 145.] (Plaintiffs claim against the City will be addressed below in section V.E.) Excessive force claims under the due process clause focus on three factors: (1) the relationship between the amount of force used and the need presented; (2) the extent of the injury inflicted; and (3) the motives of the state actor. Roska v. Peterson, 328 F.3d 1230, 1243 (10th Cir. 2003). To establish a 1983 violation under the due process clause, the alleged conduct

must do more than show that the government actor intentionally or recklessly caused injury to the plaintiff by abusing or misusing government power.... [It] must demonstrate a degree of outrageousness and a magnitude of potential or actual harm that is truly conscience shocking. Livsey v. Salt Lake County, 275 F.3d 952, 95758 (10th Cir. 2001); Uhlrig v. Harder, 64 F.3d 567, 573 (10th Cir. 1995). [W]hen unforeseen circumstances demand an officers instant judgment, even precipitate recklessness fails to inch close enough to harmful purpose to spark the shock that implicates the large concerns of the governors and the governed. County of Sacramento, 523 U.S. at 853. Conduct that is intended to injure unjustifiable by any government interest is the type of conduct most likely to rise to the level of conscience shocking. Id. at 849. In addition, courts are required to give great deference to the decisions that necessarily occur in emergency situations as opposed to those situations which permit the opportunity for deliberation by the government official. Radecki v. Barela, 146 F.3d 1227, 1231-32 (10th Cir. 1998). As to the third factor from Roska, [f]orce inspired by malice or by unwise, excessive zeal amounting to an abuse of official power that shocks the conscience may be redressed under

26

Case 1:11-cv-00645-RBJ-KMT Document 97 Filed 07/27/12 USDC Colorado Page 27 of 54

the Fourteenth Amendment. Roska, 328 F.3d at 1243. A malicious, sadistic intent can be inferred where there can be no legitimate purpose for the officers conduct. Serna v.

Colorado Dept of Corrs., 455 F.3d 1146, 1152 (10th Cir. 2006). Courts in this circuit can also rely on excessive force cases under the Eighth Amendment since the Eighth Amendment standard provides the benchmark for such claims. Craig v. Eberly, 164 F.3d 490, 495 (10th Cir. 1998). The appropriate inquiry under the Eighth Amendment is whether the force was applied in a good-faith effort to maintain or restore discipline, or maliciously and sadistically to cause harm. Northington v. Jackson, 973 F.2d 1518, 1523-24 (10th Cir. 1992)(citing Hudson v. McMillian, 503 U.S. 1, 6-7 (1992)). 3. Defendant Grimes is entitled to qualified immunity. a. No constitutional violation.

As a backdrop to analyzing the use of force used by all of the individual Defendants, the environment in which the incident took place is a critical factor. The intake area of the DDC is a large open area comprising the cooperative seating area which is surrounded by a railing and includes several rows of chairs and telephones. [SUMF, 1.] The intent of the department is to permit inmates who are being processed to wait in the cooperative seating area until they are called to approach various stations to complete the booking process. [SUMF, 2.] Given the openness of the area, cooperation by inmates, meaning that they remain calm and do not disrupt the deputies or the other waiting inmates, is essential to maintaining order in the facility. [SUMF, 2.] If an inmate is uncooperative or disruptive, the inmate is moved by DDC staff to an adjacent intake/isolation cell until the inmate is calm enough to complete the booking process.

27

Case 1:11-cv-00645-RBJ-KMT Document 97 Filed 07/27/12 USDC Colorado Page 28 of 54

[SUMF, 3-4.] The cooperative seating area can be a highly dangerous area to the deputies if security and order are not maintained. Under the DSD policy, the carotid restraint is considered non-deadly force, and it can be used in situations where violent resistance is encountered. [SUMF, 62-63.] As part of their training, deputies are instructed about the risk associated with a continuous one minute application of the hold, and also receive training that the carotid restraint should not be applied again to a conscious inmate if the restraint has already rendered the inmate unconscious from a prior application. [SUMF, 64-65.] As shown below, Grimes use of the carotid restraint was consistent with both the policy of the DSD as well as the training that he received. Before using any force against Booker, Grimes witnessed Bookers attempted assault of Gomez. [SUMF, 14.] He responded to Gomez location and after Booker ignored verbal commands, he attempted to gain control of Booker to direct him to the isolation cell, but Booker fought off the deputies. [SUMF, 15] Per his training, Grimes wanted to get Booker to the floor to better control him, to include placing him in handcuffs. [SUMF, 16.] Upon falling to the floor, Booker continued to resist by pushing, pulling, and moving his arms and legs, while continuing to ignore ongoing verbal commands. [SUMF, 17.] After Grimes again unsuccessfully attempted to gain control of Bookers arms, he decided to attempt to place Booker in a carotid restraint to restrain or control his movements so he would voluntarily stop resisting or Grimes would render Booker temporarily unconscious. [SUMF, 19.] Grimes used his right arm and placed pressure on both sides of Bookers neck, but avoided placing pressure on Bookers windpipe by placing the crook of his right arm in front of Bookers windpipe (with his elbow pointing away from Booker) with his right bicep and

28

Case 1:11-cv-00645-RBJ-KMT Document 97 Filed 07/27/12 USDC Colorado Page 29 of 54

forearm applying pressure on either side of Bookers neck, using his left arm to pull his right hand towards his own body. [SUMF, 20.] Throughout the struggle, Grimes increased and decreased the amount of pressure applied to Bookers neck as he attempted to apply the carotid restraint, and each time he lessened the pressure, Booker became more combative in his struggle resulting in Grimes increasing the pressure. [SUMF, 22.] Booker was incredibly strong and continued to struggle with Grimes and his continued movement prevented Grimes from completing the carotid restraint as evidenced Booker continuing to yell profanities, spitting while he was doing so, and his continued flailing around and struggling with the deputies. [SUMF, 21, 40.] Even more telling is the fact that Booker did not go unconscious as an effective carotid restraint typically renders the subject unconscious in roughly 5 to 20 seconds. [SUMF, ftnt. 7.] These factors establish that the carotid restraint did not have the desired effect as Booker continued to resist and be non-compliant during the entire time Grimes was holding him. And once he perceived that Booker stopped resisting, Grimes released the hold only five seconds after the TASER was removed by Rodriguez. [SUMF, 37.] Applying the factors from Roska, the amount of force used by Grimes was proportionate to the immediate and critical need to gain compliance and restore order in a dangerous area of the jail. While Plaintiff alleges that the restraint was integral to causing Bookers death, the undisputed evidence establishes that Booker continued to resist during the attempted restraint (and thus was conscious), and there is no objective medical evidence in the record that Booker suffocated as a result of the attempted restraint. Perhaps most glaring is the complete lack of evidence that Grimes was motivated by anything other than a good-faith and legitimate effort to

29

Case 1:11-cv-00645-RBJ-KMT Document 97 Filed 07/27/12 USDC Colorado Page 30 of 54

restore discipline, and there is nothing to suggest that he was motivated by malice and a sadistic intent to cause harm. Grimes did not have time to deliberate and the actions of Booker

necessitated an immediate response. This is not the type of conscience shocking behavior that establishes a due process violation. b. No clearly established law.

Given that Plaintiff cannot establish a due process violation by Grimes, the Court need not address whether the law was clearly established to find an entitlement to qualified immunity. However, the second prong of the qualified immunity analysis even more clearly mandates the dismissal of this claim. There is no Supreme Court or Tenth Circuit case which addresses the use of the carotid restraint, let alone a single case from those courts which finds that the attempted use of the carotid restraint against an inmate who disobeyed verbal commands, attempted to assault a correctional officer, and violently resisted officers attempts to restrain him was unconstitutional. Defendants also could not locate a case from another federal circuit even addressing the appropriateness of the use of the carotid restraint.12 There is also no Supreme Court or Tenth Circuit case which stands for the proposition that the carotid restraint cannot be used in tandem with other restraints (such as the TASER, OPN, control holds, or handcuffing). Plaintiff will therefore be unable to meet its burden of showing that the law was clearly established such that Grimes should have known he was violating Bookers due process rights. For this additional reason, Grimes is entitled to qualified immunity.

12

Plaintiff has throughout this litigation referred to the carotid restraint as a chokehold, and thus may argue that there is case law addressing the unconstitutionality of the chokehold. However, there is no evidence in this case, either by way of sworn testimony or objective medical evidence, suggesting that Grimes applied a chokehold to Booker or that Booker suffocated as a result of the hold.

30

Case 1:11-cv-00645-RBJ-KMT Document 97 Filed 07/27/12 USDC Colorado Page 31 of 54

4.

Defendant Rodriguez is entitled to qualified immunity. a. No constitutional violation.

Grimes eventually requested a TASER given Bookers ongoing resistance and his concern that he was becoming fatigued and Booker would free himself and pose a greater risk to the deputies. [SUMF, 31.] Rodriguez has stated that she applied the TASER to Bookers leg for several seconds, and the download from the device confirms that it was applied for a total of 8 seconds. [SUMF, 32, ftnt. 8.] The TASER was used in drive stun mode (as opposed to the probe mode) after Rodriguez told Booker that she had the device and that it would be used if he did not stop resisting. [SUMF, 32.] She applied it only after Booker ignored the warning and continued to resist despite ongoing commands to comply. [SUMF, 32.] There was only a single application of the device as it seemed to have no effect on Booker. [SUMF, 32-33.] As a preliminary matter, evaluating Plaintiffs claim against Rodriguez is complicated by the fact there exists little case law on point. TASERs are a relatively new technology, and prior to 2006, only three federal circuits had decided an excessive force case involving the use of a TASER. See Mattos v. Agarano, 590 F.3d 1082, 1089-90 (9th Cir. 2010), reversed en banc 661 F.3d 433 (9th Cir. 2011). Significantly, the majority of the cases involving use of a TASER address instances where the TASER probes were deployed (probe mode) at a resistant and combative arrestee in an effort to take the subject into custody. Fewer cases address a TASER employed in a drive-stun manner on an arrestee or pretrial detainee.13 There is little Tenth

Courts have recently differentiated between the use of a TASER in probe mode and a TASER in drive-stun mode. While using a TASER in the probe mode causes pain through a suspects entire body and has a strong incapacitating effect due to the probes interference with the suspects nervous system and muscular functioning, a TASER in drive-stun mode causes only localized and temporary pain and is non-incapacitating. See generally Brooks v. City of Seattle, 599 F.3d 1018, 1026-1028 (9th Cir. 2010), reversed 661 F.3d 433 (9th Cir. 2012). Accordingly, using a

13

31

Case 1:11-cv-00645-RBJ-KMT Document 97 Filed 07/27/12 USDC Colorado Page 32 of 54

Circuit case law addressing the use of a TASER in a confinement setting, and as such, the Court should also look to authority outside of the jurisdiction for guidance. The Tenth Circuits unpublished decision in Hunter v. Young, 238 Fed.Appx. 336 (10th Cir. 2007) is instructive and provides a sampling of decisions from other circuits about the use of the TASER in a confinement setting.14 In Hunter, deputies twice used a TASER in probe mode against an inmate who ignored verbal commands to sit on his bunk. Hunter, 238 Fed.Appx. at 337. The Hunter court found the force to be constitutional, and in relying upon cases from multiple circuits, the court noted that the use of a TASER is not per se unconstitutional when used to compel obedience by inmates. Id. at 339 (referring to Draper v. Reynolds, 369 F.3d 1270, 1278 (11th Cir. 2004)(holding that a single use of the taser gun causing a one-time shocking against a hostile, belligerent, and uncooperative arrestee to effectuate the arrest was not excessive force); Jasper v. Thalacker, 999 F.2d 353, 354 (8th Cir. 1993) (using stun gun to subdue an unruly inmate did not violate Eighth Amendment where plaintiff failed to prove that the officers used the stun gun sadistically or maliciously to cause harm); Caldwell v. Moore, 968 F.2d 595, 602 (6th Cir. 1992) (use of stun gun against disruptive prisoner to restore discipline and order does not violate Eighth Amendment); Michenfelder v. Sumner,860 F.2d 328, 336 (9th Cir. 1988) (policy of allowing use of TASER on inmate who refuses to submit to a strip search does not constitute cruel and unusual punishment). Here, after providing Booker with a verbal warning beforehand, Rodriguez used a brief, single application of the TASER in the drive stun mode to his leg in response to Bookers

TASER in a drive-stun mode is less intrusive than the use of a TASER in probe mode, and is more akin to a pain compliance technique. Id. 14 Although the Tenth Circuit does not allow citation to unpublished opinions for precedential value, unpublished opinions may be cited for persuasive value. 10th Cir. R. 32.1.

32

Case 1:11-cv-00645-RBJ-KMT Document 97 Filed 07/27/12 USDC Colorado Page 33 of 54

resistance and non-compliance with commands. There was a relationship between the level of force (pain compliance only) and the need for force given Bookers prior resistance and noncompliance at the time the TASER was applied. There is no evidence in the record that the TASER, in and of itself, inflicted any kind of injury. There is also no evidence suggesting that the TASER was used for anything other than the legitimate purpose of gaining compliance and restoring order. This is no better evidenced by the fact that the TASER was used one time for only 8 seconds in the least intrusive manner possible (drive-stun mode), and the fact that it was removed from Booker as soon as Rodriguez noticed that it was not having the desired effect. Based on the factors from Roska, Plaintiff cannot establish a due process violation as to Rodriguez. b. No clearly established law.

Addressing the second prong of the analysis, the law was not clearly established to the point that Rodriguez should have known that she could not use a one-time 8 second application of the TASER in drive stun mode to gain compliance and obedience from Booker after he had attempted to assault a deputy and continued to resist. There is also no clearly established law that would have put her on notice that a TASER could not be used while another officer was attempting a carotid restraint and another office was applying an OPN to the inmate even assuming that she knew Grimes was attempting a carotid restraint.15 For this reason, Rodriguez is entitled to qualified immunity and the excessive force claim against her should be dismissed.

15

As noted above, Rodriguez (as well as Robinette, Gomez, and Sharp) did not know that Grimes was attempting to use a carotid restraint given the position of Grimes and Booker. [SUMF, 38.]

33

Case 1:11-cv-00645-RBJ-KMT Document 97 Filed 07/27/12 USDC Colorado Page 34 of 54

5.

Defendant Sharp is entitled to qualified immunity. a. No constitutional violation.

Sharps use of force was limited to an attempt to apply the OPN while Booker was standing and the eventual application of the device on Bookers left ankle while the group was on the floor. [SUMF, 26-30.] Sharp witnessed the attempted assault of Gomez, and only applied the OPN after Booker ignored repeated commands to stop resisting. [SUMF, 14, 28.] The intent was to use the pain compliance device to stop Booker from kicking and flailing and to gain compliance with verbal commands. [SUMF, 28.] Sharp did so in the least intrusive manner given that he did not strike Booker with the OPN nor did he twist it when he applied pressure. [SUMF, 27-30.] And when Sharp released the pressure, Booker kicked his feet at him necessitating the re-application of the device. [SUMF, 30.] Sharp also removed the OPN immediately when Booker stopped resisting. [SUMF, 36.] The use of this pain compliance device was proportionate to the resistance by Booker and for the legitimate purpose of maintaining security and restoring order. There is no evidence of any significant injury to Bookers ankle or leg as a result of the use of the OPN. There is also nothing in the record to support an allegation that Sharp acted with malice or a sadistic intent to cause harm, and nothing would suggest that the application of the OPN to Bookers ankle was the type of conscience shocking behavior that would result in a due process violation. b. No clearly established law.

A review of case law in preparation of this motion failed to reveal a single case from the Supreme Court or the Tenth Circuit outlining the constitutional parameters for the use of the OPN. This lack of case law in and of itself should result in the dismissal of the excessive force

34

Case 1:11-cv-00645-RBJ-KMT Document 97 Filed 07/27/12 USDC Colorado Page 35 of 54

claim against Sharp on qualified immunity grounds. Further, there is no other case law which would have put Sharp on notice that his use of a pain compliance technique against an inmates ankle after the inmate had attempted to assault another deputy and was resisting attempts to be controlled was in violation of the due process clause. The law was also not clearly established that the application of the OPN on a resisting and assaultive inmate simultaneously with an attempted carotid restraint and attempts at handcuffing an inmate was a constitutional violation. 6. Defendants Gomez and Robinette are entitled to qualified immunity. a. No constitutional violation.

It is undisputed that Gomez use of force was limited to the following: (1) attempting to and actually grabbing onto Bookers arm as he was descending the steps into the cooperative seating area; (2) attempting to and actually securing Bookers hands so that he could be handcuffed. [SUMF, 12, 23, 25.] Robinettes use of force was even more limited than Gomez, and solely constituted attempts at handcuffing Booker on the floor to include the use of a gooseneck hold. [SUMF, 23-25.] This minimal use of force was in response to Bookers (1) refusal to comply with verbal commands, (2) refusal to enter I-8 after being instructed to do so, (3) aggressively pulling away from Gomez as she attempted to grab his arm, (4) violently swinging his elbow/arm in the direction of her head, (5) continuously pulling his hands away from the deputies on the floor, and (6) flailing his body around on the floor preventing the deputies from handcuffing him. [SUMF, 8-13, 23, and 25.] Again applying the factors from Roska, the amount of force used by Gomez and Robinette was minimal compared to the immediate and critical need to gain compliance and

35

Case 1:11-cv-00645-RBJ-KMT Document 97 Filed 07/27/12 USDC Colorado Page 36 of 54

restore order in a dangerous area of the jail. There is no evidence that any injury to Booker resulted from these deputies grabbing his arms/hands and attempting to handcuff him. And most notably, there is nothing in the record to suggest that Gomez or Robinette was motivated by anything other than a good-faith effort to restore discipline. Nothing would suggest that their minimal force in response to Bookers belligerence and unprovoked disobedience was motivated by malice and a sadistic intent to cause harm. As with the other deputies, neither deputy had time to deliberate as the actions of Booker necessitated an immediate response. This is certainly not the type of conscience shocking behavior contemplated by the due process clause. Plaintiff therefore cannot establish a due process excessive force claim against Gomez or Robinette. b. No clearly established law.

Given that Plaintiff cannot establish a due process violation by Gomez or Robinette, the Court need not address whether the law was clearly established to find an entitlement to qualified immunity. However, as with the other deputies, the second prong of the qualified immunity analysis clearly requires the dismissal of these claims. It cannot be said that the law was clearly established such that either deputy should have known that placing hands on an inmate that had repeatedly ignored commands and subsequently attempting to handcuff that inmate who had attempted to assault a deputy was in violation of the constitution. The analysis does not change because Grimes was attempting a carotid restraint and Sharp was using an OPN at the same time the officers were attempting to gain control and handcuff Booker. There is no Supreme Court or Tenth Circuit decision pre-dating the incident that would have provided Gomez or Robinette with notice of such drastic limitations on their ability to maintain security and order in a

36

Case 1:11-cv-00645-RBJ-KMT Document 97 Filed 07/27/12 USDC Colorado Page 37 of 54

confinement setting. For this even more compelling reason, Gomez and Robinette are entitled to qualified immunity. C. THE INDIVIDUAL DEFENDANTS ARE ENTITLED TO QUALIFIED IMMUNITY ON THE FAILURE TO PROVIDE MEDICAL CARE CLAIM.

Plaintiffs Third Claim for Relief is brought pursuant to 1983 and alleges that the individual Defendants should have known of Bookers life-threatening condition from the force that had been used and failed to examine, assess, or treat Booker for his condition. [Amended Complaint, Doc. No. 36, 150-151.] The allegation appears to be that the deputies should have checked Bookers vital signs during and immediately after the use of force incident. Under the due process clause, pretrial detainees are ... entitled to the degree of protection against denial of medical attention which applies to convicted inmates under the Eighth Amendment. Martinez v. Beggs, 563 F.3d 1082, 1088 (10th Cir. 2009)(citing Garcia v. Salt Lake County, 768 F.2d 303, 307 (10th Cir.1985)). A plaintiff can prevail on this type of a claim if he can establish a deliberate indifference to serious medical needs. Martinez, 563 F.3d at 1088 (internal quotations omitted.) There is both an objective and subjective component to the deliberate indifference analysis. The objective component is satisfied if the alleged harm rises to a level to be sufficiently serious as being cognizable under the Eighth Amendment, meaning that it is the harm claimed by the plaintiff that must be sufficiently serious as opposed to the symptoms presented at the time the prison employee has contact with the prisoner. Id. at 1088 (citing Mata v. Saiz ,427 F.3d 745, 752-53 (10th Cir. 2005)(internal quotations omitted)). In addition, when the allegation is a delay in medical care, it must be shown that the delay resulted in substantial harm, such as the ultimate injury, so long as the prisoner can show that the more

37

Case 1:11-cv-00645-RBJ-KMT Document 97 Filed 07/27/12 USDC Colorado Page 38 of 54

timely receipt of medical treatment would have minimized or prevented the harm. Kikumura v. Osagie, 461 F.3d 1269, 1291-1292 (10th Cir. 2006)(citing Mata, 427 F.3d at 753). To establish the subjective component of the analysis, the prisoner must show that the defendants knew he faced a substantial risk of harm and disregarded that risk, by failing to take reasonable measures to abate it. Id. at 1089 (citing Callahan v. Poppell, 471 F.3d 1155, 1159 (10th Cir. 2006)). This requires a showing that the officer knew of and disregarded an excessive risk to the inmates health or safety, that the officer was both aware of facts from which the inference could be drawn that a substantial risk of serious harm exists, and the officer must also draw that inference. Id. (citing Farmer v. Brennan, 511 U.S. 825, 837 (1994)). Distinguishable from the objective component, the symptoms displayed by the inmate are relevant, and the inquiry is whether they rose to the level that the officer knew the risk to the inmate and nonetheless chose to disregard it. Id. (citing Mata, 427 F.3d at 753). 1. No constitutional violation. a. Objective component.

It would be difficult to argue that the ultimate harm suffered by Booker did not rise to the level of being sufficiently serious to be cognizable under the Eighth Amendment. However, in a delay of medical care case, Plaintiffs must show that the harm would have been minimized or prevented had there been no delay. Here, there is no objective medical evidence suggesting within a reasonable degree of medical probability that any earlier request for treatment or actual treatment by the individual Defendants would have resulted in Booker being alive today. Any alleged delay in treatment was minimal and insufficient to rise to the level of a due process violation. The entire use of force incident (from the time Gomez first made contact with

38

Case 1:11-cv-00645-RBJ-KMT Document 97 Filed 07/27/12 USDC Colorado Page 39 of 54

Bookers arm until Grimes released Booker) lasted for 2 minutes and 55 seconds. [SUMF, 39]. The elapsed time between the end of the use of force incident and Booker being placed in I-8 was 1 minute and 37 seconds. [SUMF, 43.] The time between the deputies placing Booker in I-8 and the deputies leaving the cell was 1 minute and 29 seconds. [SUMF, 45.] After leaving the cell, Rodriguez went to notify the nurse so that Booker could be evaluated. [SUMF, 46.] Accordingly, the total amount of time between the end of the use of force incident and the deputies seeking medical attention was only 3 minutes and 6 seconds (1 minute 37 seconds plus 1 minute 29 seconds). Sharp returned to the cell 21 seconds later and first noticed that Booker was not moving. [SUMF, 47.] When it appeared for the first time that Booker potentially faced a risk of harm, Sharp and Grimes immediately summoned medical assistance. [SUMF, 47-49.] The elapsed time between Sharp returning to I-8 and a nurse arriving at the cell was 1 minute and 31 seconds. [SUMF, 50.] The total elapsed time between the completion of the use of force incident and a nurse arriving at I-8 was therefore only 4 minutes and 58 seconds. [SUMF, 51.] Not only is there no competent evidence supporting the position that earlier intervention would have saved Bookers life, but the minimal delay at issue in this case is insufficient to establish the objective component of the due process analysis entitling the individual Defendants to qualified immunity. b. Subjective component.

Plaintiffs claim also fails as they cannot establish the subjective component. There is nothing in the record establishing that the individual Defendants knew anything about Bookers medical history at the time of the incident. More importantly, there is no evidence that the individual Defendants knew of and disregarded an excessive risk to Bookers health or safety,

39

Case 1:11-cv-00645-RBJ-KMT Document 97 Filed 07/27/12 USDC Colorado Page 40 of 54

that any of the officers were both aware of facts from which the inference could be drawn that a substantial risk of serious harm exists, and that any officer drew that inference. The deputies receive training from DSD that they are required to place on inmate on his side and check vital signs after the use of the carotid restraint if the inmate goes unconscious. [SUMF, 66-67.] There is consistent testimony from the deputies that Booker continued to move and flail around all the way up to the time that the TASER was applied. [SUMF, 17, 19, 21-23, 25, 29-32.] The deputies therefore would have had no reason to believe that a substantial risk of death existed during that time frame.16 After the use of the TASER, and until the deputies placed Booker in I-8 and then left the cell, there is evidence that Booker was voluntarily moving and breathing again eliminating any reason for the deputies to believe that a substantial risk of death existed. [SUMF, 41-42, 44.] Even prior to the deputies having any reason to believe that there was a substantial risk of death, they had summoned medical aid given that Booker had been involved in a use of force. [SUMF, 46.] And when it first could be said that any of the individual Defendants had reason to believe that Booker was at risk of harm, immediate efforts were made to obtain medical aid. [SUMF, 47-49.] None of the force used by the deputies constituted deadly force or was of the magnitude that any of the deputies would have thought that a substantial risk of death existed. [SUMF, 62.] In fact, all the force was less lethal, and most of the force used was intermediate in nature or lower. Put simply, there was nothing obvious about the degree of force that was used to trigger a belief in the minds of the deputies that there existed a substantial risk of death. And there is simply no evidence in the record to establish that the individual Defendants knew of and

16

This all assumes that the individual Defendants had both a duty and the capability to monitor Bookers vital signs prior to him being fully restrained and under control.

40

Case 1:11-cv-00645-RBJ-KMT Document 97 Filed 07/27/12 USDC Colorado Page 41 of 54