Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

All For The Union Final Paper

Enviado por

xjakeknockoutDescrição original:

Título original

Direitos autorais

Formatos disponíveis

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

All For The Union Final Paper

Enviado por

xjakeknockoutDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Luck of the Draw

HST277 Objective Analysis of All for the Union Jacob Fuerst, 10/24/12

Perhaps Elisha Rhodes' mother knew something that he did not. It was one late Saturday night in April of 1861 when Elisha broke the news to his mother that he wished to enlist with the 2nd Rhode Island Volunteers of the Union Army. The next Sunday was a sorrowful one, nineteen year old Elisha writes in his diary. My mother went about with tears in her eyes he continues, until she finally conceded that if 'other mothers must make sacrifices, why should not I?' (Rhodes 4, 5). Elisha recorded his mothers sorrowful reaction in what would one day become All for the Union, a compilation of Elishas diary entries and letters during his time in the Union Army. They provide unique insight into the day to day wartime experiences of the Civil War soldier. Moreover, they expose the episodic, guerilla warfare-style battles that broke up a soldiers otherwise routine life spent drilling, marching, and waiting at camp. In keeping these records, Elisha not only documented the attempted training and discipline of Yankee regiments like his, but unwittingly illustrated that the lives of almost every soldier on both fronts were protected very little by such activities. His accounts demonstrate that Civil War battles often degenerated into guerilla warfare style combat. Soldiers on both sides perished at the hands of this because they were not equipped to handle such frenzied bloodshed. The Civil War was wrought with periods of extreme, all inclusive violence in an unfamiliar form that affected the survival of all participants; Mrs. Rhodes may have known all too well. Elisha Rhodes All for the Union reveals that combat in the American Civil War frequently descended into frenzied, guerilla style warfare that participating soldiers training, experience and military discipline did not effectively prepare them for. As documented by the diary entries of Elisha Rhodes, combat in the Civil War often occurred as a kind of bloody guerilla warfare that left troops from both sides scattered and vulnerable, separated from their regiments. During Elishas time as a private in the 2nd Rhode Island Volunteer Infantry, his 1

regiment marched for weeks before finally hearing gunshots in the distance. Elisha here admits his ignorance to the fact that violence was so close by. This, however, reflects the relative ignorance of the soldier in general they knew very little of what was to come and had to learn to be ready for battle at a moments notice. The careful planning and execution of combat by Civil War higher-ups, like officers or generals, was information excluded to many field soldiers like Elisha, leaving them vulnerable to conflict that could happen when they least expected it. Nonetheless, Elisha's regiment proceeded to engage in an unforeseen battle with surrounding Rebels where, at one point, the woods and roads were soon filled with fleeing men, both Union and Confederate (Rhodes 21). Rhodes records multiple battles that degenerated like this; such gory chaos, where bodies piled three or four high, had come directly after Rhodes ignorantly believed his regiment victorious, only to be again fired upon by rebels so unexpectedly that they were forced to retreat. In an unsigned letter possessed by Rhodes, an anonymous soldier wrote to him about similarly chaotic events where all the troops retreated precipitately in the greatest confusion under a perfect avalanche of balls (Rhodes 30). He proceeded to recount how his regiment was again attacked, guerilla-style, when seeking shelter in nearby woods. This was very destructive, he says sorrowfully, where baggage wagons were piled one upon another... and men lay all around, some dead, others wounded, and dying. Much like this, the horrid things that Elisha and other Civil War soldiers endured were representative of the sheer lethality of guerilla warfare-style combat that the Civil Wars battles often became. The terrifying nature of the wars guerilla-style battles in All for the Union thus rendered the prior military training of almost all soldiers unsuccessful and, at times, plain irrelevant to increasing their chances of survival. In training, Elisha writes of drilling for hours on end and nothing more. But during Elisha's recount of his aforementioned first battle, he remembers his smooth bore rifle becoming so foul that he had to jam it against a fence to place the cartridge correctly (Rhodes 18). Training had not prepared him for the woes of weapon failure. And while that one blunder alone could have easily 2

cost him his life when compared to the mass death surrounding him, Elisha remained unscathed; however, his nearby Colonel Slocum was not as lucky. While frantically climbing a similar fence, Slocum received a bullet from rear to front through the top of his head (Rhodes 20). Its clear that the outcomes of the two men were due to happenstance, not training, and Rhodes alludes to his own knowledge of this fact here: I feel to thank God that he has kept me within his fold while so many have gone astray... (Rhodes 50). This same fate-dependent (rather than training-dependent) survival during the Civil War is personified in another letter possessed by Rhodes which was written by Corporal Samuel J. English. He documents a battle that became so desperate that while attempting to cross a bridge on his hands and knees, another fellow soldier directly next to him and also crawling was quite literally shot in half (Rhodes 26). No degree of prior training ensured a soldiers' survival against hit-or-miss bloodshed of this magnitude. Englishs story further shows that soldiers like him faced situations where gunfire came from all sides and with such pandemonium that survival became a game of odds, not a reflection of prior training. A year later, at the Charleston city crossroads in June of 1862, Elisha inadvertently exposes the same issues with training in the enemy Confederates. While his regiment engaged in guerilla warfare tactics, concealed in the woods, a rebel troop came right up to them but did not manage to injure a single Yankee. Had training prepared the rebels for this sort of guerrilla warfare, they may not have missed every single shot and allowed Elisha's troop to take many prisoners (Rhodes 66). There was a final aspect of warfare at the time that no amount of training could prepare a soldier for handling the limits of their sanity. After one particularly gruesome battle, Elisha matter-of-factually states that the excitement had caused some men to lose their minds (Rhodes 33). No matter the situation, though, the battles of the American Civil War were recurrent displays of chaotic destruction that no amount of training could adequately protect a soldier against any more than the prayers of Elisha could. Even wartime experience, a source of both glory and confidence for many veterans, could not 3

effectively protect the lives of American Civil War soldiers against elements of guerilla warfare combined with increasingly lethal weaponry. All for the Union shows time and time again that experienced men fell victim to many of the same fates as those of the common soldier. Case in point: Elisha, still a private, lives through his first battle while his Colonel Slocum is shot multiple times in the head and ankle (Rhodes 20). In fact, four Union officers died in that same battle. For reference, it took Elisha himself years (and much of the book) to reach the rank of colonel similarly lengthy years of experience failed to protect the other officers that perished. The deadliness of the Civil War's conflict, when it happened, affected whoever it pleased. The letter from Samuel J. English recalled seeing a man get struck in the chest with a bomb shell and get blown to pieces, effectively demonstrating that the weapons now prevalent in warfare of the time could strike anyone anywhere (Rhodes 25). The sheer range and striking power of the Civil War's smooth bore rifles and exploding cannon shells meant that no one, not even a person of rank or experience, would have their safety guaranteed not even in the security of their camps. An incident on July 9th, 1861 documents a caisson explosion in Rhodes' camp that left two soldiers dead, three wounded. ...it gives us our first idea of the terrible effect of gunpowder, Elisha writes of the event (Rhodes 14). The battles of the Civil War were fought with elements of guerilla warfare that neither rank nor experience could protect against, especially when the wars weaponry made combat all the more total. Furthermore, the lax and often inconsistent administration of discipline in the armies of the Civil War actually proved to potentiate the wars deadliness to all soldiers. The beginning of Rhodes' military service in All for the Union exposes the Union's inconsistent use of discipline. Rhodes is instructed by his Captain, Captain Steere, to remain in camp while the rest of his regiment marches. Elisha documents his response: I objected to this plan and finally told my Captain that if he left me in camp I would run away and join the Regiment on the road as soon as it became dark. His stunning display of direct disobedience is entertained, surprisingly, by his Captain who only attempts to 4

convince Elisha that he is too slight built to march. Rhodes claims that he'll go with or without orders and his Captain gives in to his demands (Rhodes 15). Here, discipline in the Union army is handled with a soft hand. That a private deemed weak by his superiors can force his way into battle is seemingly uncharacteristic of military conduct and exposes the undisciplined nature of the wars participating soldiers. When Rhodes and his regiment make a march to Washington after retreating from a bloody encounter with rebels, Rhodes repeatedly lies down in the mud and refuses to continue. Despite immediate irony that Elishas actions reinforce his captains concerns about his ability to march, the only prodding he receives is that of fellow soldiers who urge Rhodes to continue on (Rhodes 22). Unlike the Prussian troops of the Napoleonic Wars, who threatened to leave cavalry member Nadezhda Durova behind during intense marches, Elisha receives only encouragement. Such inconsistency is seen again when in late October of 1863, a few stray shots fired at pigs that attack our outposts warranted an angry response from brigade Headquarters, that threatened all sorts of punishment to anyone in Rhodes' brigade that continued shooting swine. That punishment went undocumented and Elisha's witty response sums up it up nicely: ...officers are like policemen and are never around while mischief is being done, (Rhodes 120). The ease at which all soldiers could engage in disobedience serves to further explain the many instances in which battles left soldiers scattered, disorganized and potentially dead. As evidenced by All for the Union, the training, experience and discipline of all soldiers in the American Civil War did not prove advantageous to their survival because of the tendency for battles to degenerate into chaotic, guerilla-style warfare that soldiers were unprepared for. Elisha Rhodes' mother knew it from the moment he set his heart on enlisting his chances of coming home rested almost completely in the hands of fate. The training, discipline and eventual experience of soldiers like Rhodes may have made him into a soldier, but as documented firsthand in All for the Union, being the best soldier alive did not mean that one would stay alive. The bouts of overwhelming bloodshed made the 5

battles of the Civil War particularly gruesome and often let them descend into disarray. A soldier's chance at survival, regardless of his military background, felt nearly powerless at the hands of this fact. As for soldiers like Elisha Rhodes, who even wrote that he'd finish out his duty or die in service, the American Civil War provided the exact coin flip he was after (Rhodes 236).

Works Cited

Rhodes, Elisha Hunt and Rhodes, Robert Hunt. All for the Union. Vintage Civil War Library, New York. 1992.

Você também pode gostar

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryNo EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (231)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)No EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Nota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (121)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaNo EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (266)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingNo EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (399)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItNo EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (838)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerNo EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (271)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeNo EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (5794)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyNo EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (2259)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersNo EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (344)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnNo EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (234)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreNo EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (1090)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceNo EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (895)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureNo EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (474)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaNo EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (45)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)No EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Nota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (98)

- Culture and Customs of UkraineDocumento219 páginasCulture and Customs of UkraineJurij Andruhovych75% (4)

- Bukovsky - Is The European Union The New Soviet Union Transcript) (R)Documento4 páginasBukovsky - Is The European Union The New Soviet Union Transcript) (R)pillulful100% (1)

- International Relations Theory-Routledge (2022)Documento205 páginasInternational Relations Theory-Routledge (2022)Muhammad MateenAinda não há avaliações

- Warmachine: VengeanceDocumento142 páginasWarmachine: VengeanceJimmy100% (2)

- Field Artillery Journal - Aug 1945Documento67 páginasField Artillery Journal - Aug 1945CAP History LibraryAinda não há avaliações

- The Official Newsletter of The Naval Airship AssociationDocumento36 páginasThe Official Newsletter of The Naval Airship Associationgustavojorge12Ainda não há avaliações

- Volunteer ExperienceDocumento3 páginasVolunteer ExperiencexjakeknockoutAinda não há avaliações

- Carlina A. Vanjo: Career SummaryDocumento1 páginaCarlina A. Vanjo: Career SummaryxjakeknockoutAinda não há avaliações

- Personal Statement 5Documento2 páginasPersonal Statement 5xjakeknockoutAinda não há avaliações

- Carlina A. Vanjo: Career SummaryDocumento1 páginaCarlina A. Vanjo: Career SummaryxjakeknockoutAinda não há avaliações

- Diversity StatementDocumento1 páginaDiversity StatementxjakeknockoutAinda não há avaliações

- Personal Statement 5Documento2 páginasPersonal Statement 5xjakeknockoutAinda não há avaliações

- Carlina A. Vanjo: Career SummaryDocumento2 páginasCarlina A. Vanjo: Career SummaryxjakeknockoutAinda não há avaliações

- Carlina A. Vanjo: Career SummaryDocumento2 páginasCarlina A. Vanjo: Career SummaryxjakeknockoutAinda não há avaliações

- FERPA WaiverDocumento1 páginaFERPA WaiverxjakeknockoutAinda não há avaliações

- Pac Ferpa Waiver 2016Documento1 páginaPac Ferpa Waiver 2016xjakeknockoutAinda não há avaliações

- Work ExperienceDocumento4 páginasWork ExperiencexjakeknockoutAinda não há avaliações

- Diversity StatementDocumento1 páginaDiversity StatementxjakeknockoutAinda não há avaliações

- Updated ResumeDocumento2 páginasUpdated ResumexjakeknockoutAinda não há avaliações

- Ferpa Waiver For Pac 1.17.14Documento1 páginaFerpa Waiver For Pac 1.17.14xjakeknockoutAinda não há avaliações

- Volunteer ExperienceDocumento1 páginaVolunteer ExperiencexjakeknockoutAinda não há avaliações

- Carlina A. Vanjo: Career SummaryDocumento2 páginasCarlina A. Vanjo: Career SummaryxjakeknockoutAinda não há avaliações

- Carlina A. Vanjo: Career SummaryDocumento2 páginasCarlina A. Vanjo: Career SummaryxjakeknockoutAinda não há avaliações

- Work ExperienceDocumento4 páginasWork ExperiencexjakeknockoutAinda não há avaliações

- Work ExperienceDocumento4 páginasWork ExperiencexjakeknockoutAinda não há avaliações

- Carlina A. Vanjo: Career SummaryDocumento2 páginasCarlina A. Vanjo: Career SummaryxjakeknockoutAinda não há avaliações

- Volunteer ExperienceDocumento1 páginaVolunteer ExperiencexjakeknockoutAinda não há avaliações

- Ferpa Waiver For Pac 1.17.14Documento1 páginaFerpa Waiver For Pac 1.17.14xjakeknockoutAinda não há avaliações

- READ THESE TIPS BEFORE FILLING OUT THE GPA CALCULATION GRID (Which Appears On The Next Tab Within This Excel Document)Documento41 páginasREAD THESE TIPS BEFORE FILLING OUT THE GPA CALCULATION GRID (Which Appears On The Next Tab Within This Excel Document)xjakeknockoutAinda não há avaliações

- Carlina A. Vanjo: Career SummaryDocumento2 páginasCarlina A. Vanjo: Career SummaryxjakeknockoutAinda não há avaliações

- Depaul University 1 East Jackson Boulevard Chicago, Il 60604Documento5 páginasDepaul University 1 East Jackson Boulevard Chicago, Il 60604xjakeknockout100% (1)

- Work ExperienceDocumento4 páginasWork ExperiencexjakeknockoutAinda não há avaliações

- Graduate School InformationDocumento2 páginasGraduate School InformationxjakeknockoutAinda não há avaliações

- Updated ResumeDocumento1 páginaUpdated ResumexjakeknockoutAinda não há avaliações

- Shadowing ExperienceDocumento1 páginaShadowing ExperiencexjakeknockoutAinda não há avaliações

- SSR TSRPT-1Documento4 páginasSSR TSRPT-1xjakeknockoutAinda não há avaliações

- New York Times War and Memory LessonDocumento39 páginasNew York Times War and Memory Lessonapi-218930601Ainda não há avaliações

- Confrontation 2.0Documento65 páginasConfrontation 2.0FranklinAinda não há avaliações

- Heliborne InsertionDocumento6 páginasHeliborne InsertionJotaAinda não há avaliações

- Anastasopoulos, Political Initiatives From The Bottom UpDocumento24 páginasAnastasopoulos, Political Initiatives From The Bottom UpAladin KučukAinda não há avaliações

- D Day Fact Sheet The SuppliesDocumento1 páginaD Day Fact Sheet The SuppliesmossyburgerAinda não há avaliações

- Ww2 A Crhonlogie August 1944Documento109 páginasWw2 A Crhonlogie August 1944ekielmanAinda não há avaliações

- Israel-Palestine Conflict (An Apple of Discord in Middle East)Documento7 páginasIsrael-Palestine Conflict (An Apple of Discord in Middle East)Malick Sajid Ali IlladiiAinda não há avaliações

- Vortex 9Documento12 páginasVortex 9255sectionAinda não há avaliações

- Linchpin Analysis ExampleDocumento2 páginasLinchpin Analysis Examplekcope412Ainda não há avaliações

- Using and Understanding Mathematics 6th Edition Bennett Test BankDocumento36 páginasUsing and Understanding Mathematics 6th Edition Bennett Test Bankpanchway.coccyxcchx100% (37)

- Hercules and Balarama - The Symbolic and Historical ConnectionsDocumento25 páginasHercules and Balarama - The Symbolic and Historical ConnectionsDouglas Varun AndersonAinda não há avaliações

- Forge World Imperial Armour Sixth Edition Vehicle UpdatesDocumento3 páginasForge World Imperial Armour Sixth Edition Vehicle UpdatesZiac LortabAinda não há avaliações

- Savage Wars of Peace: Case Studies of Pacification in The Philippines, 1900-1902Documento181 páginasSavage Wars of Peace: Case Studies of Pacification in The Philippines, 1900-1902Gen. H.P. Flashman100% (1)

- Journal International Law N2-09 N1-10Documento260 páginasJournal International Law N2-09 N1-10David PataraiaAinda não há avaliações

- CFP Inogs 2024 Conference v4Documento4 páginasCFP Inogs 2024 Conference v4Sanjana RahmanAinda não há avaliações

- Course Outline - International Relations Since 1648-1945 BSIR-2nd (R)Documento2 páginasCourse Outline - International Relations Since 1648-1945 BSIR-2nd (R)Aasma IsmailAinda não há avaliações

- Babbar KhalsaDocumento1 páginaBabbar KhalsaShalss Rockkss100% (1)

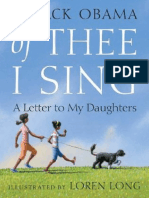

- COPII Barack Obama of Thee I Sing. A Letter To My DaughtersDocumento41 páginasCOPII Barack Obama of Thee I Sing. A Letter To My DaughtersIonela Jac100% (2)

- Bar TalDocumento68 páginasBar TalRude FloAinda não há avaliações

- The 29 February Us-Iea Agreement and Implications For Ngos: Table of ContentsDocumento18 páginasThe 29 February Us-Iea Agreement and Implications For Ngos: Table of ContentsM. Yaqub AhmadiAinda não há avaliações

- CasablancaDocumento71 páginasCasablancapicilohatAinda não há avaliações

- Law and Order SituationDocumento2 páginasLaw and Order SituationIRFAN KARIMAinda não há avaliações

- PhilHis HaliliDocumento301 páginasPhilHis Haliliinfoman201086% (7)

- Battle Cry Zulu WarDocumento4 páginasBattle Cry Zulu WarPat RisAinda não há avaliações