Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

Citigroup Frank Letter in Response

Enviado por

Daniel FisherTítulo original

Direitos autorais

Formatos disponíveis

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Citigroup Frank Letter in Response

Enviado por

Daniel FisherDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Theodore H. Frank Center for Class Action Fairness 1718 M Street NW, No.

236 Washington, DC 20036 (703) 203-3848 tfrank@gmail.com January 24, 2013

The Honorable Sidney H. Stein U.S. District Judge Daniel Patrick Moynihan U.S. Courthouse 500 Pearl St. New York, NY 10007-1312 Courtroom: 23A Fax: (212) 805-7924

VIA FACSIMILE Re: In re Citigroup Inc. Securities Litigation, No. 07 Civ. 9901(SHS) Request for Informal Discovery Conference Pursuant to L. R. 37.2

Your Honor, I have filed a pro se objection to the Rule 23(h) request in the above titled case (Dkt. No. 181) and a declaration and expert report in support of this objection (Dkt. No. 182); I plan to supplement it with at least one additional expert report by the new March 8 deadline. Plaintiffs have taken the objection seriously enough that they devoted twenty-three pages of their brief (Dkt. No. 195) and over forty-five pages of a separate declaration (Dkt. No. 196) to respond to it. (Plaintiffs also provide a chart listing twentyfive objections I have previously been involved in. Dkt. No. 196-3. They fail to mention that I won outright victories, fee reductions, or settlement improvements in seventeen of those twenty-five objections, with another four of the remaining eight still pending resolution. It is unclear why they think this track record militates against my substantive objection.) As documented in my earlier declaration, I have made inquiries to class counsel regarding whether they were willing to voluntarily provide me with discovery

Honorable Sidney H. Stein January 24, 2013 page 2 regarding their request for $100.3 million award. Specifically, I seek (1) to depose plaintiffs two experts that submitted opinions regarding the reasonableness of class counsels fee request, and (2) to discover information regarding the hourly rates assigned to the contract attorneys in class counsels lodestar report. Class counsel has refused my requests and argued to both me and this Court that I am not entitled to any discovery. See Reply Memorandum in Support of Request for Fees, Dkt. 195 at 24-25. While objector discovery is not absolute, the rule in the Second Circuit is that a class action settlement offer by a lower court must be overturned if it failed to allow objectors to develop on the record facts going to the propriety of the settlement. Detroit v. Grinnell Corp., 495 F.2d 448, 462 (2d Cir. 1974) (emphasis added and quotations omitted). The limited discovery I seek is appropriate and necessary for several reasons. First, the settlements structure prevents an adversarial process regarding class counsels fee request. Plaintiffs rely upon Malchman v. Davis, 761 F.2d 893 (2d Cir. 1985), as justification for their stonewalling, but that case supports the limited discovery that I seek. The Second Circuit first noted that On first impression, the district court's denial of discovery appears in conflict with an earlier opinion requiring scrutiny of the issue on which objectors wanted discovery. Id. at 898. But Malchman affirmed the denial of discovery only because defendants had conducted discovery at length on the issues where the objectors wished discovery. Id. at 898-99. Here in contrast, there has been no discovery or testing of the claims made in the fee request. The settlement has a clear sailing provision permitting class counsel to make their $100.3 million request without challenge from the defendants. See Settlement, Dkt. 155-1, 8. Such a clause by its very nature deprives the court of the advantages of the adversary process. Weinberger v. Great N. Nekoosa Corp., 925 F.2d 518, 525 (1st Cir. 1991). Class counsels submissions in connection with their fee request are untested, and will remain untested without the requested discovery. Denying discovery here would unfairly prejudice class members interests in responding to class counsels fee request. Second, the requested discovery seeks necessary information that has not been disclosed or otherwise subject to discovery. My objection contains numerous complaints regarding the soundness of the methodologies plaintiffs experts employed and the sufficiency of the factual predicates on which they rely. See Objection, Dkt. 181 at 6, 8, 14-19. Plaintiffs experts have not been deposed and examination is necessary to test such opinions. Vigorous cross-examination is an essential minimum of testing shaky but admissible evidence. Daubert v. Merrell Dow Pharmaceuticals, Inc., 509 US 579 (1993) (citing Rock v. Arkansas, 483 U.S. 44, 61 (1987)); accord Gayton v. McCoy, 593 F.3d 610, 616, 619 (7th Cir. 2010). If an objector doesnt cross-examine these experts, no

Honorable Sidney H. Stein January 24, 2013 page 3 one will; it would be most efficient for the cross-examination to occur in deposition and be summarized in briefing, rather than take place for hours at a fairness hearing. Unless the Court is to exclude the expert witnesses entirely, depositions are required. Information regarding the contract attorneys on class counsels lodestar report is also necessary. A comparison between the lodestar report and the attorney resumes submitted by class counsel reveals that $28.1 million of the $51.4 million lodestar amount was based on work performed by over 40 contract attorneys. See Exhibit E to Memo in Support of Fees, Dkt. 171-5. As set forth in my objection, these contract attorneys were likely being paid between $20 to $45/hour because they were performing low-skilled work. See Objection, Dkt. 181 at 11-12. (And it turns out my objection was insufficiently cynical: reporting from an independent journalist on this case reveals that the attorneys were paid $32/hour at most, and otherwise contradicts the assertions in plaintiffs briefing and declarations. See Daniel Fisher, Class-Action Firms Capitalize On Wretched Market For Law-School Grads, Forbes.com (Jan. 4, 2013).) Yet lead counsel assigned greatly exaggerated hourly rates for those contract attorneys between $325 to $550/hour. See id. This is wrong. The lodestar figure should be based on market rates in line with those [rates] prevailing in the community for similar services by lawyers of reasonably comparable skill, experience, and reputation. Reiter v. MTA N.Y. City Transit Auth., 457 F.3d 224, 232 (2d Cir. 2006) (emphasis added). Simply put, Michelangelo should not charge Sistine Chapel rates for painting a farmers barn. Ursic v. Bethlehem Mines, 719 F.2d 670, 677 (3d Cir. 1983). Accord, e.g., Detroit v. Grinnell Corp., 560 F.2d 1093, 1100 (2d Cir. 1977); Tucker v. City of New York, 704 F. Supp. 2d 347, 356 n.7 (S.D.N.Y. 2010); In re KeySpan Corp. Sec. Litig., CV 2001-5852 (ARR) (MDG), 2005 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 29068, at *53-*54 (E.D.N.Y. Aug. 25, 2005) (rejecting use of $275/hour attorneys to do document review). And there is no question that attorneys who have to resort to $32/hour jobs in the unpleasant conditions of temporary contract work are not even Michelangelo. Discovery is necessary to test plaintiffs assertions about the tasks of the contract attorneys. For example, plaintiffs claim that they needed highly-skilled attorneys to do the work that was assigned to them. There is readily available evidence that could prove this that plaintiffs did not submit to the Court. For example, did Hudson Legal (and other third-party providers) advertise for specific skills and experience? (The indiscriminate $32/hour rate reported by Fisherpaid both to experienced attorneys and to recent law-school grads (and a 1998 graduate who was not admitted to the bar until 2009, see Dkt. 196 158)certainly suggests a cannon-fodder scenario.) Did plaintiffs put the contract-work out for bid, and, if so, how was the project described? It

Honorable Sidney H. Stein January 24, 2013 page 4 would be telling if plaintiffs are representing to the court that the attorneys were performing highly-skilled work meritorious of $550/hour rates, but represented to third-party providers that the work was not specialized in order to negotiate lowerpriced proposals for contract-attorney work. What do the contracts with the third-party providers say? (And even if two of the contract attorneys were doing substantive work (Dkt. 196 103), it doesnt mean that all $26 million of lodestar attributed to the attorneys was for substantive work.) Other aspects of the declaration are suspiciously phrased in the passive tense that leads to the inference that a third party was the actor. E.g., Dkt. 196 129 states that contract attorneys were established in offices one block away. By whom? Who was responsible for that overhead? Unless the Court is willing to draw negative inferences and reject class counsels contentions out of hand, it is necessary to test these issues through the discovery process. With respect to the multiplier, class counsel argues that they incur substantial risk in engaging in securities cases, but they never directly dispute my demonstration (Dkt. 181 56-67) that the vast majority of hours and investment class action attorneys make in securities cases are in ultimately successful cases, and that risk is thus relatively low. (Indeed, class counsel inadvertently concede my argument with respect to this case by acknowledging that most of their lodestar was not incurred until 2011, well after the motion to dismiss was decided in November 2010. Dkt. 196 96 ff.) It would be easy enough for each class counsel to provide a list of all PSLRA cases resolved between 2008 and 2011, the lodestar invested in each case, and the ultimate fees awarded. If, as I contend, the overwhelming majority of hours are expended in cases where lodestar is recovered, a 1.9 multiplier is unnecessary to incentivize attorneys to engage in securities litigationespecially when so much of the risk actually reflects an investment in temporary attorneys paid $32/hour who can be terminated costlessly at cases end. This is a purely empirical question, measurable by objective evidence that does not need to be resolved by a battle of the experts: for what percentage of hours do PSLRA class action attorneys fail to recover their lodestar? Again, unless the Court is willing to draw negative inferences and reject class counsels contentions out of hand, discovery is necessary. I have other information that I do not wish to disclose at this time that I believe refutes claims in the class counsels sworn declaration, but cannot develop that impeaching information without limited document and deposition discoverythe reasonable investigation that Rule 11 requires. Third, the discovery I seek is limited to information regarding my specific objections to class counsels fee request. I am not seeking information regarding the

Honorable Sidney H. Stein January 24, 2013 page 5 underlying merits of the litigation and do not seek to re-litigate this matter. Indeed, the limited discovery will not cause delay in these proceedings and, if permitted to proceed at the beginning of February, should be complete well in advance of the fairness hearing. Permitting such limited discovery is particularly appropriate in light of class counsels large Rule 23(h) request. The court owes a fiduciary duty to absent class members, and the best way to test the claims of entitlement to $100.3 million of the classs money is through the adversary process. Plaintiffs claim to be entitled to ask for that money all but ex parte should be rejected. I am now prepared to file a motion to compel discovery. Local Civ. R. 37.2 provides that such a motion shall not be heard unless counsel for the moving party first requested an informal conference with the Court by letter and such request has either been denied or the discovery dispute has not been resolved as a consequence of such a conference. Please let this letter serve as a request for that informal conference. Very truly yours, /s/ Theodore H. Frank Theodore H. Frank cc: Counsel of record via email

Você também pode gostar

- PWC Colonial Liability Order 122817Documento92 páginasPWC Colonial Liability Order 122817Daniel Fisher100% (1)

- DOJ Brief Against CFPB 3-17-17Documento33 páginasDOJ Brief Against CFPB 3-17-17Daniel Fisher100% (1)

- Erhart V Boi Order 021417Documento34 páginasErhart V Boi Order 021417Daniel FisherAinda não há avaliações

- Syngenta Motion SummaryDocumento43 páginasSyngenta Motion SummaryDaniel FisherAinda não há avaliações

- GP Informational BriefDocumento52 páginasGP Informational BriefDaniel Fisher100% (1)

- Drummond Memorandum Opinion On Crime FraudDocumento50 páginasDrummond Memorandum Opinion On Crime FraudPaulWolfAinda não há avaliações

- Hearing 1Documento156 páginasHearing 1Daniel FisherAinda não há avaliações

- Federal Judge Strikes Down Sanctuary Cities OrderDocumento49 páginasFederal Judge Strikes Down Sanctuary Cities Ordermolliereilly100% (8)

- Presidential Executive Order On Promoting Energy Independence and Economic GrowthDocumento7 páginasPresidential Executive Order On Promoting Energy Independence and Economic GrowthPBS NewsHour100% (3)

- Zillow DismissDocumento43 páginasZillow DismissDaniel FisherAinda não há avaliações

- De 8-8 Affidavit of J. Noah HageyDocumento14 páginasDe 8-8 Affidavit of J. Noah HageyDaniel FisherAinda não há avaliações

- LTR Joint Ps (Moulton) (Apr3 2015)Documento16 páginasLTR Joint Ps (Moulton) (Apr3 2015)Daniel FisherAinda não há avaliações

- Amex Antisteering Settlement DenialDocumento44 páginasAmex Antisteering Settlement DenialDaniel Fisher100% (1)

- Hill V SEC ALJ OrderDocumento45 páginasHill V SEC ALJ OrderDaniel FisherAinda não há avaliações

- NYCAL Not. & Affirm - Joint Motion For Stay & Exhs 1-5Documento296 páginasNYCAL Not. & Affirm - Joint Motion For Stay & Exhs 1-5Daniel FisherAinda não há avaliações

- Nygard ResponseDocumento80 páginasNygard ResponseDaniel FisherAinda não há avaliações

- Collins TCPA Fee ContestDocumento229 páginasCollins TCPA Fee ContestDaniel FisherAinda não há avaliações

- Rubinstein DisbarDocumento22 páginasRubinstein DisbarDaniel FisherAinda não há avaliações

- O'Neill vs. Saudi Arabia Amended PleadingDocumento157 páginasO'Neill vs. Saudi Arabia Amended PleadingDaniel FisherAinda não há avaliações

- 10 - 14 - 14 Order Denying Norcold SettlementDocumento13 páginas10 - 14 - 14 Order Denying Norcold SettlementDaniel FisherAinda não há avaliações

- Lohan v. Take-Two InteractiveDocumento10 páginasLohan v. Take-Two InteractivepospislawAinda não há avaliações

- Robbins Geller Sanctions OrderDocumento18 páginasRobbins Geller Sanctions OrderDaniel FisherAinda não há avaliações

- 8 18 2014 Order On Motion For SanctionsDocumento14 páginas8 18 2014 Order On Motion For SanctionsDaniel FisherAinda não há avaliações

- Blixseth 8-16-10 Bcy DecisionDocumento135 páginasBlixseth 8-16-10 Bcy DecisionDaniel FisherAinda não há avaliações

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)No EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Nota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (98)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeNo EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (5795)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItNo EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceNo EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (895)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersNo EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (345)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingNo EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (400)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureNo EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryNo EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (231)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerNo EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (271)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaNo EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (266)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaNo EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (45)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnNo EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (234)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyNo EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (2259)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreNo EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)No EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Nota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (121)

- Nursing Philosophy Apa PaperDocumento7 páginasNursing Philosophy Apa Paperapi-449016836Ainda não há avaliações

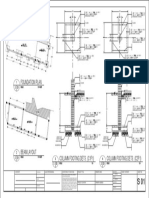

- Foundation Plan: Scale 1:100 MTSDocumento1 páginaFoundation Plan: Scale 1:100 MTSJayson Ayon MendozaAinda não há avaliações

- (2010) Formulaic Language and Second Language Speech Fluency - Background, Evidence and Classroom Applications-Continuum (2010)Documento249 páginas(2010) Formulaic Language and Second Language Speech Fluency - Background, Evidence and Classroom Applications-Continuum (2010)Như Đặng QuếAinda não há avaliações

- Tour Preparations Well Under WayDocumento1 páginaTour Preparations Well Under WayjonathanrbeggsAinda não há avaliações

- PCU 200 Handbook 2018-19 PDFDocumento177 páginasPCU 200 Handbook 2018-19 PDFVica CapatinaAinda não há avaliações

- Model Control System in Triforma: Mcs GuideDocumento183 páginasModel Control System in Triforma: Mcs GuideFabio SchiaffinoAinda não há avaliações

- Week 4Documento5 páginasWeek 4عبدالرحمن الحربيAinda não há avaliações

- Transform Your Appraisal Management Process: Time-Saving. User-Friendly. Process ImprovementDocumento10 páginasTransform Your Appraisal Management Process: Time-Saving. User-Friendly. Process ImprovementColby EvansAinda não há avaliações

- 001 The Crib SheetDocumento13 páginas001 The Crib Sheetmoi moiAinda não há avaliações

- 1167 Nine Planets in TamilDocumento1 página1167 Nine Planets in TamilmanijaiAinda não há avaliações

- Technical Analysis CourseDocumento51 páginasTechnical Analysis CourseAkshay Chordiya100% (1)

- Lampiran 18-Lesson Plan 02Documento5 páginasLampiran 18-Lesson Plan 02San Louphlii ThaAinda não há avaliações

- Book Review "The TKT Course Clil Module"Documento8 páginasBook Review "The TKT Course Clil Module"Alexander DeckerAinda não há avaliações

- Auto Loan Application Form - IndividualDocumento2 páginasAuto Loan Application Form - IndividualKlarise EspinosaAinda não há avaliações

- Vishnu Dental College: Secured Loans Gross BlockDocumento1 páginaVishnu Dental College: Secured Loans Gross BlockSai Malavika TuluguAinda não há avaliações

- Nutrition Science by B Srilakshmi PDFDocumento6 páginasNutrition Science by B Srilakshmi PDFRohan Rewatkar46% (35)

- "Written Statement": Tanushka Shukla B.A. LL.B. (2169)Documento3 páginas"Written Statement": Tanushka Shukla B.A. LL.B. (2169)Tanushka shuklaAinda não há avaliações

- Sow English Year 4 2023 2024Documento12 páginasSow English Year 4 2023 2024Shamien ShaAinda não há avaliações

- Revalida ResearchDocumento3 páginasRevalida ResearchJakie UbinaAinda não há avaliações

- The Spartacus Workout 2Documento13 páginasThe Spartacus Workout 2PaulFM2100% (1)

- Research Poster 1Documento1 páginaResearch Poster 1api-662489107Ainda não há avaliações

- Indian Banking - Sector Report - 15-07-2021 - SystematixDocumento153 páginasIndian Banking - Sector Report - 15-07-2021 - SystematixDebjit AdakAinda não há avaliações

- Banana Oil LabDocumento5 páginasBanana Oil LabjbernayAinda não há avaliações

- Short Questions From 'The World Is Too Much With Us' by WordsworthDocumento2 páginasShort Questions From 'The World Is Too Much With Us' by WordsworthTANBIR RAHAMANAinda não há avaliações

- Formulating Affective Learning Targets: Category Examples and KeywordsDocumento2 páginasFormulating Affective Learning Targets: Category Examples and KeywordsJean LabradorAinda não há avaliações

- Studi Penanganan Hasil Tangkapan Purse Seine Di KM Bina Maju Kota Sibolga Study of Purse Seine Catches Handling in KM Bina Maju Sibolga CityDocumento8 páginasStudi Penanganan Hasil Tangkapan Purse Seine Di KM Bina Maju Kota Sibolga Study of Purse Seine Catches Handling in KM Bina Maju Sibolga CitySavira Tapi-TapiAinda não há avaliações

- Warcraft III ManualDocumento47 páginasWarcraft III Manualtrevorbourget78486100% (6)

- KGTE February 2011 ResultDocumento60 páginasKGTE February 2011 ResultSupriya NairAinda não há avaliações

- Areopagitica - John MiltonDocumento1 páginaAreopagitica - John MiltonwehanAinda não há avaliações

- Intensive Care Fundamentals: František Duška Mo Al-Haddad Maurizio Cecconi EditorsDocumento278 páginasIntensive Care Fundamentals: František Duška Mo Al-Haddad Maurizio Cecconi EditorsthegridfanAinda não há avaliações