Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

Abolish Social Studies

Enviado por

Dave GreenDireitos autorais

Formatos disponíveis

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Abolish Social Studies

Enviado por

Dave GreenDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Autumn 2012 Abolish Social Studies Michael Knox Beran Born a century ago, the pseudo-discipline has outlived

its uselessness. Emerging as a force in American education a century ago, social studies was inte nded to remake the high school. But its greatest effect has been in the elementa ry grades, where it has replaced an older way of learning that initiated childre n into their culture with one that seeks instead to integrate them into the soci al group. The result was a revolution in the way America educates its young. The old learning used the resources of culture to develop the child s individual pote ntial; social studies, by contrast, seeks to adjust him to the mediocrity of the social pack. Why promote the socialization of children at the expense of their individual dev elopment? A product of the Progressive era, social studies ripened in the faith that regimes guided by collectivist social policies could dispense with the comp etitive striving of individuals and create, as educator George S. Counts wrote, t he most majestic civilization ever fashioned by any people. Social studies was to mold the properly socialized citizens of this grand future. The dream of a worl d regenerated through social planning faded long ago, but social studies persist s, depriving children of a cultural rite of passage that awakened what Coleridge called the principle and method of self-development in the young. The poverty of social studies would matter less if children could make up its cu ltural deficits in English class. But language instruction in the elementary sch ools has itself been brought into the business of socializing children and has c eased to use the treasure-house of culture to stimulate their minds. As a result , too many students today complete elementary school with only the slenderest kn owledge of a culture that has not only shaped their civilization but also done m uch to foster individual excellence. In 1912, the National Education Association, today the largest labor union in th e United States, formed a Committee on the Social Studies. In its 1916 report, T he Social Studies in Secondary Education, the committee opined that if social st udies (defined as studies that relate to man as a member of a social group ) took a place in American high schools, students would acquire the social spirit, and the youth of the land would be steadied by an unwavering faith in humanity. This was an allusion to the religion of humanity preached by the French social thinker August e Comte, who believed that a scientifically trained ruling class could build a b etter world by curtailing individual freedom in the name of the group. In Comtia n fashion, the committee rejected the idea that education s primary object was the cultivation of the individual intellect. Individual interests and needs, educatio n scholar Ronald W. Evans writes in his book The Social Studies Wars, were for t he committee secondary to the needs of society as a whole. The Young Turks of the social studies movement, known as Reconstructionists becaus e of their desire to remake the social order, went further. In the 1920s, Recons tructionists like Counts and Harold Ordway Rugg argued that high schools should be incubators of the social regimes of the future. Teachers would instruct stude nts to discard dispositions and maxims derived from America s individualistic ethos, w rote Counts. A professor in Columbia s Teachers College and president of the Ameri can Federation of Teachers, Counts was for a time enamored of Joseph Stalin. Aft er visiting the Soviet Union in 1929, he published A Ford Crosses Soviet Russia, a panegyric on the Bolsheviks new society. Counts believed that in the future, all

important forms of capital would have to be collectively owned, and in his 1932 ess ay Dare the Schools Build a New Social Order?, he argued that teachers should enli st students in the work of social regeneration. Like Counts, Rugg, a Teachers College professor and cofounder of the National Co uncil for the Social Studies, believed that the American economy was flawed beca use it was utterly undesigned and uncontrolled. In his 1933 book The Great Technol ogy, he called for the social reconstruction and scientific design of the economy, a rguing that it was now axiomatic that the production and distribution of goods ca n no longer be left to the vagaries of chance specifically to the unbridled compet itions of self-aggrandizing human nature. There must be central control and superv ision of the entire [economic] plant by trained and experienced technical personne l. At the same time, he argued, the new social order must socialize the vast propo rtion of wealth and outlaw the activities of middlemen who didn t contribute to the pr oduction of true value. Rugg proposed new materials of instruction that shall illustrate fearlessly and dra matically the inevitable consequence of the lack of planning and of central cont rol over the production and distribution of physical things. . . . We shall diss eminate a new conception of government one that will embrace all of the collective activities of men; one that will postulate the need for scientific control and operation of economic activities in the interest of all people; and one that wil l successfully adjust the psychological problems among men. Rugg himself set to work composing the new materials of instruction. In An Introdu ction to Problems of American Culture, his 1931 social studies textbook for juni or high school students, Rugg deplored the lack of planning in American life : Repeatedly throughout this book we have noted the unplanned character of our civ ilization. In every branch of agriculture, industry, and business this lack of p lanning reveals itself. For instance, manufacturers in the United States produce billions of dollars worth of goods without scientific planning. Each one produce s as much as he thinks he can sell, and then each one tries to sell more than hi s competitors. . . . As a result, hundreds of thousands of owners of land, mines , railroads, and other means of transportation and communication, stores, and bu sinesses of one kind or another, compete with one another without any regard for the total needs of all the people. . . . This lack of national planning has ind eed brought about an enormous waste in every outstanding branch of industry. . . . Hence the whole must be planned. Rugg pointed to Soviet Russia as an example of the comprehensive control that Am erica needed, and he praised Stalin s first Five-Year Plan, which resulted in mill ions of deaths from famine and forced labor. The amount of coal to be mined each year in the various regions of Russia, Rugg told the junior high schoolers readin g his textbook, is to be planned. So is the amount of oil to be drilled, the amount of wheat, co rn, oats, and other farm products to be raised. The number and size of new facto ries, power stations, railroads, telegraph and telephone lines, and radio statio ns to be constructed are planned. So are the number and kind of schools, college s, social centers, and public buildings to be erected. In fact, every aspect of the economic, social, and political life of a country of 140,000,000 people is b eing carefully planned! . . . The basis of a secure and comfortable living for t he American people lies in a carefully planned economic life. During the 1930s, tens of thousands of American students used Rugg s social studie s textbooks. Toward the end of the decade, school districts began to drop Rugg s textbooks beca use of their socialist bias. In 1942, Columbia historian Allan Nevins further un dermined social studies premises when he argued in The New York Times Magazine th at American high schools were failing to give students a thorough, accurate, and

intelligent knowledge of our national past in so many ways the brightest national record in all world history. Nevins s was the first of many critiques that would co unteract the collectivist bias of social studies in American high schools, where old-fashioned history classes have long been the cornerstone of the social studie s curriculum. Yet possibly because school boards, so vigilant in their superintendence of the high school, were not sure what should be done with younger children, social stu dies gained a foothold in the primary school such as it never obtained in the se condary school. The chief architect of elementary school social studies was Paul Hanna, who entered Teachers College in 1924 and fell under the spell of Counts and Rugg. We cannot expect economic security so long as the [economic] machine is conceived as an instrument for the production of profits for private capital ra ther than as a tool functioning to release mankind from the drudgery of work, Han na wrote in 1933. Hanna was no less determined than Rugg to reform the country through education. P upils must be indoctrinated with a determination to make the machine work for so ciety, he wrote. His methods, however, were subtler than Rugg s. Unlike Rugg s textbo oks, Hanna s did not explicitly endorse collectivist ideals. The Hanna books conta in no paeans to central planning or a command economy. On the contrary, the illu strations have the naive innocence of the watercolors in Scott Foresman s Dick and Jane readers. The books depict an idyllic but familiar America, rich in materia l goods and comfortably middle-class; the fathers and grandfathers wear suits an d ties and white handkerchiefs in their breast pockets. Not only the pictures but the lessons in the books are deceptively innocuous. It is in the back of the books, in the notes and interpretive outlines, that Hanna s muggles in his social agenda by instructing teachers how each lesson is to be in terpreted so that children learn desirable patterns of acting and reacting in dem ocratic group living. A lesson in the second-grade text Susan s Neighbors at Work, for example, which describes the work of police officers, firefighters, and othe r public servants, is intended to teach concerted action and cooperation in obeying commands and well-thought-out plans which are for the general welfare. A lesson in Tom and Susan, a first-grade text, about a ride in grandfather s red car is mea nt to teach children to move from absorption in self toward consideration of what is best in a group situation. Lessons in Peter s Family, another first-grade text, seek to inculcate the idea of socially desirable work and cooperative labor. Hanna s efforts to promote behavior traits conducive to group living would be less obj ectionable if he balanced them with lessons that acknowledge the importance of i deals and qualities of character that don t flow from the group individual exertion, liberty of action, the necessity at times of resisting the will of others. It i s precisely Coleridge s principle of individual self-development that is lost in Han na s preoccupation with social development. In the Hanna books, the individual is perpetually sunk in the impersonality of the tribe; he is a being defined solely by his group obligations. The result is distorting; the Hanna books fail to sho w that the prosperous America they depict, if it owes something to the impulse t o serve the community, owes as much, or more, to the free striving of individual s pursuing their own ends.

Hanna s spirit is alive and well in the American elementary school. Not only Scott Foresman but other big scholastic publishers among them Macmillan/McGraw-Hill and Houghton Mifflin Harcourt publish textbooks that dwell continually on the communa l group and on the activities that people undertake for its greater good. Lesson s from Scott Foresman s second-grade textbook Social Studies: People and Places (2 003) include Living in a Neighborhood, We Belong to Groups, A Walk Through a Communit y, How a Community Changes, Comparing Communities, Services in Our Community, Our Cou y Is Part of Our World, and Working Together. The book s scarcely distinguishable twi n, Macmillan/McGraw-Hill s We Live Together (2003), is suffused with the same grou

p spirit. Macmillan/McGraw-Hill s textbook for third-graders, Our Communities (200 3), is no less faithful to the Hanna model. The third-grade textbooks of Scott F oresman and Houghton Mifflin Harcourt (both titled Communities) are organized on similar lines, while the fourth-grade textbooks concentrate on regional communi ties. Only in the fifth grade is the mold shattered, as students begin the seque ntial study of American history; they are by this time in sight of high school, where history has long been paramount. Today s social studies textbooks will not turn children into little Maoists. The g roup happy-speak in which they are composed is more fatuous than polemical; Hann a s Reconstructionist ideals have been so watered down as to be little more than b analities. The ultimate goal of the social studies, according to Michael Berson, a coauthor of the Houghton Mifflin Harcourt series, is to instigate a response tha t spreads compassion, understanding, and hope throughout our nation and the glob al community. Berson s textbooks, like those of the other publishers, are generally faithful to this flabby, attenuated Comtism. Yet feeble though the books are, they are not harmless. Not only do they do too little to acquaint children with their culture s ideals of individual liberty and initiative; they promote the socialization of the child at the expense of the de velopment of his own individual powers. The contrast between the old and new app roaches is nowhere more evident than in the use that each makes of language. The old learning used language both to initiate the child into his culture and to d evelop his mind. Language and culture are so intimately related that the Greeks, who invented Western primary education, used the same word to designate both: p aideia signifies both culture and letters (literature). The child exposed to a p articular language gains insight into the culture that the language evolved to d escribe for far from being an artifact of speech only, language is the master ligh t of a people s thought, character, and manners. At the same time, language particul arly the classic and canonical utterances of a people, its primal poetry has a uni que ability to awaken a child s powers, in part because such utterances, Plato say s, sink furthest into the depths of the soul. Social studies, because it is designed not to waken but to suppress individualit y, shuns all but the most rudimentary and uninspiring language. Social studies t extbooks descend constantly to the vacuity of passages like this one, from Peopl e and Places:

Children all around the world are busy doing the same things. They love to play games and enjoy going to school. They wish for peace. They think that adults sho uld take good care of the Earth. How else do you think these children are like e ach other? How else do you think they are like you? The language of social studies is always at the same dead level of inanity. Ther e is no shadow or mystery, no variation in intensity or alteration of pitch no rom ance, no refinement, no awe or wonder. A social studies textbook is a desert of linguistic sterility supporting a meager scrub growth of commonplaces about commu nity, neighborhood, change, and getting involved. Take the arid prose in Our Communiti s: San Antonio, Texas, is a large community. It is home to more than one million pe ople, and it is still growing. People in San Antonio care about their community and want to make it better. To make room for new roads and houses, many old tree s must be cut down. People in different neighborhoods get together to fix this b y planting. It might be argued that a richer and more subtle language would be beyond thirdgraders. Yet in his Third Eclectic Reader, William Holmes McGuffey, a nineteenth -century educator, had eight-year-olds reading Wordsworth and Whittier. His nine -year-olds read the prose of Addison, Dr. Johnson, and Hawthorne and the poetry of Shakespeare, Milton, Byron, Southey, and Bryant. His ten-year-olds studied th

e prose of Sir Walter Scott, Dickens, Sterne, Hazlitt, and Macaulay and the poet ry of Pope, Longfellow, Shakespeare, and Milton. McGuffey adapted to American conditions some of the educational techniques that were first developed by the Greeks. In fifth-century BC Athens, the language of Homer and a handful of other poets formed the core of primary education. With th e emergence of Rome, Latin became the principal language of Western culture and for centuries lay at the heart of primary- and grammar-school education. McGuffe y had himself received a classical education, but conscious that nineteenth-cent ury America was a post-Latin culture, he revised the content of the old learning even as he preserved its underlying technique of using language as an instrumen t of cultural initiation and individual self-development. He incorporated, in hi s Readers, not canonical Latin texts but classic specimens of English prose and poetry. Because the words of the Readers bit deep deeper than the words in today s social st udies textbooks do they awakened individual potential. The writer Hamlin Garland a cknowledged his deep obligation to McGuffey for the dignity and literary grace of h is selections. From the pages of his readers I learned to know and love the poem s of Scott, Byron, Southey, and Words- worth and a long line of the English mast ers. I got my first taste of Shakespeare from the selected scenes which I read i n these books. Not all, but some children will come away from a course in the old learning stirred to the depths by the language of Blake or Emerson. But no stud ent can feel, after making his way through the groupthink wastelands of a social studies textbook, that he has traveled with Keats in the realms of gold. It might be objected that primers like the McGuffey Readers were primarily inten ded to instruct children in reading and writing, something that social studies d oesn t pretend to do. In fact, the Readers, like other primers of the time, were o nly incidentally language manuals. Their foremost function was cultural: they us ed language both to introduce children to their cultural heritage and to stimula te their individual self-culture. The acultural, group biases of social studies might be pardonable if cultural learning continued to have a place in primary-sc hool English instruction. But primary-school English or language arts, as it has com e to be called no longer introduces children, as it once did, to the canonical lan guage of their culture; it is not uncommon for public school students today to r each the fifth grade without having encountered a single line of classic English prose or poetry. Language arts has become yet another vehicle for the socializa tion of children. A recent article by educators Karen Wood and Linda Bell Soares in The Reading Teacher distills the essence of contemporary language-arts instr uction, arguing that teachers should cultivate not literacy in the classic sense but critical literacy, a pedagogic approach to reading that focuses on the politic al, sociocultural, and economic forces that shape young students lives. For educators devoted to the social studies model, the old learning is anathema precisely because it liberates individual potential. It releases the powers of a young soul, the classicist educator Werner Jaeger wrote, breaking down the restrai nts which hampered it, and leading into a glad activity. The social educators hav e revised the classic ideal of education expressed by Pindar: Become what you are has given way to Become what the group would have you be. Social studies verbal dra bness is the means by which its contrivers starve the self of the sustenance tha t nourishes individual growth. A stunted soul can more easily be reduced to an a cquiescent dullness than a vital, growing one can; there is no readier way to re duce a people to servile imbecility than to cut them off from the traditions of their language, as the Party does in George Orwell s 1984. Indeed, today s social studies theorists draw on the same social philosophy that O rwell feared would lead to Newspeak. The Social Studies Curriculum: Purposes, Pr oblems, and Possibilities, a 2006 collection of articles by leading social studi es educators, is a socialist smorgasbord of essays on topics like Marxism and Cri

tical Multicultural Social Studies and Decolonizing the Mind for World-Centered Gl obal Education. The book, too, reveals the pervasive influence of Marxist thinker s like Peter McLaren, a professor of urban schooling at UCLA who advocates a genu ine socialist democracy without market relations, venerates Che Guevara as a secul ar saint, and regards the individual self as a delusion, an artifact of the materia l relations which produced it capitalist production, masculinist economies of power a nd privilege, Eurocentric signifiers of self/other identifications, all the parap hernalia of bourgeois imposture. For such apostles of the social pack, Whitman s So ng of Myself, Milton s and Tennyson s soul within, Spenser s my self, my inward self I me n, and Wordsworth s aspiration to be worthy of myself are expressions of naive faith in a thing that dialectical materialism has revealed to be an accident of matter , a random accumulation of dust and clay. The test of an educational practice is its power to enable a human being to real ize his own promise in a constructive way. Social studies fails this test. Purge it of the social idealism that created and still inspires it, and what remains is an insipid approach to the cultivation of the mind, one that famishes the sou l even as it contributes to what Pope called the progress of dulness. It should be abolished. Michael Knox Beran, a contributing editor of City Journal, is the author of Forg e of Empires 1861 1871: Three Revolutionary Statesmen and the World They Made and Pathology of the Elites, among other books. http://www.city-journal.org/printable.php?id=8564

Você também pode gostar

- Traditional Chinese Medicine Is An OddDocumento9 páginasTraditional Chinese Medicine Is An OddDave GreenAinda não há avaliações

- The New Abortion BattlegroundDocumento4 páginasThe New Abortion BattlegroundDave GreenAinda não há avaliações

- On TransienceDocumento2 páginasOn TransienceDave GreenAinda não há avaliações

- 2013 Quotas and Longline ClosureDocumento4 páginas2013 Quotas and Longline ClosureDave GreenAinda não há avaliações

- France's Cul-De-SacDocumento3 páginasFrance's Cul-De-SacDave GreenAinda não há avaliações

- Portrait of The Artist As A CavemanDocumento8 páginasPortrait of The Artist As A CavemanDave GreenAinda não há avaliações

- Why This Gigantic Intelligence ApparatusDocumento3 páginasWhy This Gigantic Intelligence ApparatusDave GreenAinda não há avaliações

- The Problem With Psychiatry, The DSM,'Documento3 páginasThe Problem With Psychiatry, The DSM,'Dave GreenAinda não há avaliações

- The Dead Are More VisibleDocumento2 páginasThe Dead Are More VisibleDave GreenAinda não há avaliações

- The Me, Me, Me' WeddingDocumento4 páginasThe Me, Me, Me' WeddingDave GreenAinda não há avaliações

- Hieber - Language Endangerment & NationalismDocumento34 páginasHieber - Language Endangerment & NationalismDave GreenAinda não há avaliações

- Language and The Socialist-Calculation ProblemDocumento7 páginasLanguage and The Socialist-Calculation ProblemDave GreenAinda não há avaliações

- Journey Through The Checkout RacksDocumento4 páginasJourney Through The Checkout RacksDave GreenAinda não há avaliações

- Egypt's High Value On VirginityDocumento3 páginasEgypt's High Value On VirginityDave Green100% (1)

- Against Environmental PanicDocumento14 páginasAgainst Environmental PanicDave GreenAinda não há avaliações

- Double Helix Meets God ParticleDocumento1 páginaDouble Helix Meets God ParticleDave GreenAinda não há avaliações

- How A Doctor Came To Believe in Medical MarijuanaDocumento2 páginasHow A Doctor Came To Believe in Medical MarijuanaDave GreenAinda não há avaliações

- Language As ActionDocumento3 páginasLanguage As ActionDave GreenAinda não há avaliações

- Big Data Is Not Our MasterDocumento2 páginasBig Data Is Not Our MasterDave GreenAinda não há avaliações

- The Lost BoysDocumento3 páginasThe Lost BoysDave GreenAinda não há avaliações

- The Constitutional Amnesia of The NSA Snooping ScandalDocumento5 páginasThe Constitutional Amnesia of The NSA Snooping ScandalDave GreenAinda não há avaliações

- Is 'Austerity' Responsible For The Crisis in Europe?Documento8 páginasIs 'Austerity' Responsible For The Crisis in Europe?Dave GreenAinda não há avaliações

- The Numbers Don't LieDocumento4 páginasThe Numbers Don't LieDave GreenAinda não há avaliações

- The Lost BoysDocumento3 páginasThe Lost BoysDave GreenAinda não há avaliações

- To Understand Risk, Use Your ImaginationDocumento3 páginasTo Understand Risk, Use Your ImaginationDave GreenAinda não há avaliações

- A Dark Night IndeedDocumento12 páginasA Dark Night IndeedDave GreenAinda não há avaliações

- Red Menace or Paper TigerDocumento6 páginasRed Menace or Paper TigerDave GreenAinda não há avaliações

- Dis-Enclosure (The Deconstruction of Christianity)Documento202 páginasDis-Enclosure (The Deconstruction of Christianity)Dave GreenAinda não há avaliações

- The High Cost of FreeDocumento7 páginasThe High Cost of FreeDave GreenAinda não há avaliações

- Sympathy DeformedDocumento5 páginasSympathy DeformedDave GreenAinda não há avaliações

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItNo EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (838)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureNo EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (474)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeNo EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (5783)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceNo EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (890)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)No EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Nota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (98)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingNo EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (399)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryNo EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnNo EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (234)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaNo EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (265)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersNo EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (344)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerNo EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (271)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyNo EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (2219)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaNo EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreNo EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)No EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Nota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (119)

- TaxGenie Introduction For Banks PDFDocumento27 páginasTaxGenie Introduction For Banks PDFsandip sawantAinda não há avaliações

- Layher Allround Industri Stillas 2015 - Engelsk - Utskrift.2Documento68 páginasLayher Allround Industri Stillas 2015 - Engelsk - Utskrift.2cosmin todoran100% (1)

- Collage of Business and Economics Department of Management (MSC in Management Extension Program)Documento4 páginasCollage of Business and Economics Department of Management (MSC in Management Extension Program)MikealayAinda não há avaliações

- Seminar Assignments Ticket Vending MachineDocumento13 páginasSeminar Assignments Ticket Vending MachineCandy SomarAinda não há avaliações

- Ipw - Proposal To OrganizationDocumento3 páginasIpw - Proposal To Organizationapi-346139339Ainda não há avaliações

- Diss Q1 Week 7-8Documento5 páginasDiss Q1 Week 7-8Jocelyn Palicpic BagsicAinda não há avaliações

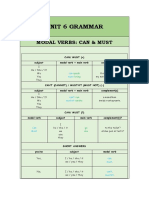

- Grammar - Unit 6Documento3 páginasGrammar - Unit 6Fátima Castellano AlcedoAinda não há avaliações

- Remedial 2 Syllabus 2019Documento11 páginasRemedial 2 Syllabus 2019Drew DalapuAinda não há avaliações

- Bollinger, Ty M. - Cancer - Step Outside The Box (2009)Documento462 páginasBollinger, Ty M. - Cancer - Step Outside The Box (2009)blah80% (5)

- Mrs.V.Madhu Latha: Assistant Professor Department of Business Management VR Siddhartha Engineering CollegeDocumento14 páginasMrs.V.Madhu Latha: Assistant Professor Department of Business Management VR Siddhartha Engineering CollegesushmaAinda não há avaliações

- HR CONCLAVE DraftDocumento7 páginasHR CONCLAVE DraftKushal SainAinda não há avaliações

- Roy FloydDocumento2 páginasRoy FloydDaniela Florina LucaAinda não há avaliações

- Old English Vs Modern GermanDocumento12 páginasOld English Vs Modern GermanfonsecapeAinda não há avaliações

- Static and Dynamic ModelsDocumento6 páginasStatic and Dynamic ModelsNadiya Mushtaq100% (1)

- Beginners Guide To Sketching Chapter 06Documento30 páginasBeginners Guide To Sketching Chapter 06renzo alfaroAinda não há avaliações

- Task 2 AmberjordanDocumento15 páginasTask 2 Amberjordanapi-200086677100% (2)

- Problem Set 1Documento5 páginasProblem Set 1sxmmmAinda não há avaliações

- 10, Services Marketing: 6, Segmentation and Targeting of ServicesDocumento9 páginas10, Services Marketing: 6, Segmentation and Targeting of ServicesPreeti KachhawaAinda não há avaliações

- Virl 1655 Sandbox July v1Documento16 páginasVirl 1655 Sandbox July v1PrasannaAinda não há avaliações

- Cooking Taoshobuddha Way Volume 2Documento259 páginasCooking Taoshobuddha Way Volume 2Taoshobuddha100% (3)

- (Progress in Mathematics 1) Herbert Gross (Auth.) - Quadratic Forms in Infinite Dimensional Vector Spaces (1979, Birkhäuser Basel)Documento432 páginas(Progress in Mathematics 1) Herbert Gross (Auth.) - Quadratic Forms in Infinite Dimensional Vector Spaces (1979, Birkhäuser Basel)jrvv2013gmailAinda não há avaliações

- KM UAT Plan - SampleDocumento10 páginasKM UAT Plan - Samplechristd100% (1)

- Docu53897 Data Domain Operating System Version 5.4.3.0 Release Notes Directed AvailabilityDocumento80 páginasDocu53897 Data Domain Operating System Version 5.4.3.0 Release Notes Directed Availabilityechoicmp50% (2)

- Mock Exam Part 1Documento28 páginasMock Exam Part 1LJ SegoviaAinda não há avaliações

- Dialogue CollectionDocumento121 páginasDialogue CollectionYo Yo Moyal Raj69% (13)

- Tabel Laplace PDFDocumento2 páginasTabel Laplace PDFIlham Hendratama100% (1)

- Designing Organizational Structure: Specialization and CoordinationDocumento30 páginasDesigning Organizational Structure: Specialization and CoordinationUtkuAinda não há avaliações

- 300 Signs and Symptoms of Celiac DiseaseDocumento7 páginas300 Signs and Symptoms of Celiac DiseaseIon Logofătu AlbertAinda não há avaliações

- Ajzen - Constructing A Theory of Planned Behavior QuestionnaireDocumento7 páginasAjzen - Constructing A Theory of Planned Behavior QuestionnaireEstudanteSax100% (1)

- v4 Nycocard Reader Lab Sell Sheet APACDocumento2 páginasv4 Nycocard Reader Lab Sell Sheet APACholysaatanAinda não há avaliações