Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

Data Mining MetaAnalysis

Enviado por

paparountasDireitos autorais

Formatos disponíveis

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Data Mining MetaAnalysis

Enviado por

paparountasDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

International Journal of Systems Biology and Biomedical Technologies, 1(3), 1-39, July-September 2012 1

Data Mining and Meta-Analysis on DNA Microarray Data

Triantafyllos Paparountas, Biomedical Sciences Research Center Alexander Fleming, Greece Maria Nefeli Nikolaidou-Katsaridou, Biomedical Sciences Research Center Alexander Fleming, Greece Gabriella Rustici, European Molecular Biology Laboratory-European Bioinformatics Institute, UK Vasilis Aidinis, Biomedical Sciences Research Center Alexander Fleming, Greece

ABSTRACT

Microarray technology enables high-throughput parallel gene expression analysis, and use has grown exponentially thanks to the development of a variety of applications for expression, genetics and epigenetic studies. A wealth of data is now available from public repositories, providing unprecedented opportunities for meta-analysis approaches, which could generate new biological information, unrelated to the original scope of individual studies. This study provides a guideline for identification of biological significance of the statistically-selected differentially-expressed genes derived from gene expression arrays as well as to suggest further analysis pathways. The authors review the prerequisites for data-mining and meta-analysis, summarize the conceptual methods to derive biological information from microarray data and suggest software for each category of data mining or meta-analysis. Keywords: Biological Information, Data Mining, Gene Networks, Meta-Analysis, Microarray

INTRODUCTION

The ability to investigate an organisms entire genomic sequence has revolutionized biological sciences. One aspect of this phenomenon was the fabrication of gene microarrays in the late 1980s (Fodor et al., 1991). Array based highthroughput gene expression analysis is widely used in many research fields; gene expression microarrays have been used in numerous

DOI: 10.4018/ijsbbt.2012070101

applications, including the identification of novel genes associated with diseases, most notably cancers (Lee, 2006; Kim et al., 2005; Al Moustafa et al., 2002; Lancaster et al., 2006), the tumors classification (Perez-Diez, Morgun, & Shulzhenko, 2007; Nguyen & Rocke, 2002; Ray, 2011; Dagliyan, Uney-Yuksektepe, Kavakli, & Turkay, 2011; Best et al., 2003) and the prediction of patient outcome (Mischel, Cloughesy, & Nelson, 2004; Simon, 2003; Futschik, Sullivan, Reeve, & Kasabov, 2003; Michiels, Koscielny, & Hill, 2005; Liu, Li, & Wong, 2005), as well

Copyright 2012, IGI Global. Copying or distributing in print or electronic forms without written permission of IGI Global is prohibited.

2 International Journal of Systems Biology and Biomedical Technologies, 1(3), 1-39, July-September 2012

as the -cell line related- drug chemosensitivity identification (Amundson et al., 2000; Dan et al., 2002; Kikuchi et al., 2003; Sax & El-Deiry, 2003; Ikeda, Jinno, & Shirane, 2007; Baggerly & Coombes, 2009; Ory et al., 2011). Typically, a microarray experiment generates a list of genes that have been identified as statistically significant differentially expressed (DEGs). Following this ensues the real challenge of assigning biological significance to the results and reconstructing pathways of interactions among DEGs. Several software tools for pathway analysis, gene ontology analysis and gene prioritization are routinely used for identifying common features in lists of DEGs. As the quantity and size of microarray datasets continues to grow (Table 2, Microarray repositories), researchers are provided with a rich data resource, but also face interoperability and data management issues. The primary data should be stored in a MIAME (Minimum Information About Microarray Expression) compliant format, which is a set of guidelines outlining the minimum information that should be included when describing a microarray experiment. It is required in order to facilitate the interpretation of the experimental results unambiguously and to potentially reproduce the experiment (Brazma et al., 2001). Complimentary to the standardization of data storage, workflows (School of Computer Science, 2008) (Table 3, Holistic Approaches) offer a solution to data management and analysis issues as they enable the automated and systematic use of distributed bioinformatics data and applications from the scientists desktop. In order to address reliability concerns as well as other performance, quality, and data analysis issues, the National Center for Toxicological Research, NCTR, has initiated the MAQC, MicroArray Quality Control project, (Shi et al., 2006, 2010), in response to the FDAs (U.S. Food and Drug Administration, n.d.) Critical Path Initiative (Coons, 2009; Mahajan & Gupta, 2010; Woodcock & Woosley, 2008). The main target of this initiative is to develop guidelines for microarray data analysis and provide the public with large reference datasets.

1. PREREQUISITES FOR DATA MINING

Generating high quality microarray data requires applying stringent quality control measures and best practices at each individual step of the process, starting with choosing the most appropriate experimental design for the study, the correct experimental platform, the protocols for sample preparation, processing, and ultimately ending with the data analysis approach for normalization and statistical analysis. (Chuaqui et al., 2002) provides a short review on the validation of primary analysis methods, (Allison, Cui, Page, & Sabripour, 2006; Dupuy & Simon, 2007; Ioannidis et al., 2009; Shi et al., 2010) inform on reasons of result discrepancies after reanalysis of raw data across different teams, while (Troester, Millikan, & Perou, 2009) provide a short list of guidelines for statistical analysis and reporting of microarray studies.

1.1. Experimental Design

Experimental design is one of the most important aspects of a successful experiment related to the identification of differential gene expression patterns. Proper experimental design is crucial to ensure that the biological questions of interest can be answered and that this can be done accurately. Appropriate experimental design (Churchill, 2002; Festing & Altman, 2002; Qiu, 2007; Shaw, Festing, Peers, & Furlong, 2002) allows a more accurate identification of DEGs and prediction of false positives (Benjamini & Hochberg, 1995; Reiner, Yekutieli, & Benjamini, 2003; Wolfinger et al., 2001). Fundamental principles of experimental design are simplicity, replication & statistical power (Festing & Altman, 2002) and bias prevention through randomization & blocking (Damaraju, 2005; Johnson & Besselsen, 2002).

1.1.1. Replication

The effects of the: Treatment-group, subject, sample, gene, probe and noise are the major sources of variability in microarray experiments. Ideally to estimate the statistically significant

Copyright 2012, IGI Global. Copying or distributing in print or electronic forms without written permission of IGI Global is prohibited.

International Journal of Systems Biology and Biomedical Technologies, 1(3), 1-39, July-September 2012 3

changes, while accounting for the noise introduced and unwanted variance factors, replication should be done at the level of the group, the subject and the probe. Replication safeguards against Type I errors (False positive) and thus ensures results of high statistical significance (Rao, 2009). Issues that should be taken into consideration when designing an experiment are: the aim of the experiment, the finances governing the number of slides and the amount of biological material required, design extensibility, and validation method. These factors determine the number of biological replicates or, in the case of few biological replicates, the number of technical replicates that should be used in the experiment (Wei, Li, & Bumgarner, 2004) (Figure 1). The number of replicates (Dobbin & Simon, 2005) depends on the type of array technology chosen (Irizarry et al., 2005), the dye bias (Dobbin, Kawasaki, Petersen, & Simon, 2005), the quality of manufacturing (Mecham et al., 2004), the specific number of arrayed genes and the tolerance level of false positives (Wang, Hessner, Wu, Pati, & Ghosh, 2003). When high variance within group signal is expected (de Reynies et al., 2006), higher numbers of replicates per group are needed, to account for false negatives (see statistical power). The term technical replicates refers to multiple arrays hybridized, with RNA isolated from a single sample, or multiple replicates of a single gene on the surface of an array. The term biological replicates refers to RNA samples isolated from multiple individuals of a population treatment and/or group, each hybridized to a different microarray or a different array in the case of multi-welled chips. Technical replicates are used mainly as quality control and reproducibility of the method, whereas biological replicates are used to strengthen the statistical power to detect significantly DEGs.

design, referred as power analysis, allows the calculation of the minimum number of replicates that are needed to detect an effect of a given size (Festing & Altman, 2002). Experiments utilizing subjects with homogenous genetic background need fewer subjects to achieve a good statistical power. This equals to ability of detection of smaller treatment responses with fewer animals (Festing & Altman, 2002). Useful software to calculate power are G*power (Faul, Erdfelder, Buchner, & Lang, 2009; Faul, Erdfelder, Lang, & Buchner, 2007) and NCSS PASS (NCSS inc. Utah, USA). On his article (Churchill, 2002) described a simple way to calculate statistical power. The method has evolved since but this approach still holds value, mainly due to its simplicity. According to Churchill, analysis can be carried out by determination of the degrees of freedom or Df. Df may be calculated in the following way: first count the number of independent units; in case of multiple treatment factors all combinations that occur should be calculated. From this sum subtract the number of distinct treatments to identify the Df. The Df score should be more than 5 in order to ensure that the experiment has enough statistical power to efficiently do analysis based on biological variance.

1.1.3. Randomization

Randomization in microarray experiments is related to: a. the randomization of samples hybridization and b. the probe placement on the arrays. In the first case randomization accounts for bias in expression levels because of the batch processing effect (for a microarray allowing one sample placed on one array) or the position effect (for a microarray allowing multiple samples placed on one array) (Rao, 2009). Randomization during the positioning of the probes on each array on the other hand ensures no propagation of spatial effects during intensity measurement. If the placement of probes is not randomized, measurements from the training stage to validation stage may have different biases (Verdugo, Deschepper, Munoz,

1.1.2. Statistical Power

Statistical power refers to the adequacy of a statistical test to avoid a Type II error (False negative). The evaluation of the power of a

Copyright 2012, IGI Global. Copying or distributing in print or electronic forms without written permission of IGI Global is prohibited.

4 International Journal of Systems Biology and Biomedical Technologies, 1(3), 1-39, July-September 2012

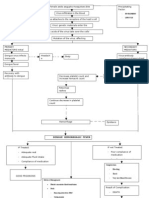

Figure 1. Elucidation of differences between technical and biological replicates

Pomp, & Churchill, 2009; Barnes, Freudenberg, Thompson, Aronow, & Pavlidis, 2005). It should be noted in their assessment whether such probe-transcript mapping influences expressions reported by the same platform (Kitchen et al., 2011) allege that no such correlation was observed.

1.1.4. Blocking and Block Randomization

Extraneous factors may affect the gene expression that is quantified through the array platforms. The phenomenon that occurs when it is not possible to disentangle the effects of two or more extraneous factors is referred as confounding (Everitt, 2007; Pearl, 1998). The two effects are usually referred to as aliases. Common examples of confounding factors are gender and age in epidemiological studies, where a trait can also be attributed to the age or gender and not only on the treatment. In the case of microarrays the technology behind array construction may as well be a confounding factor. During an experiment there are two stages when confounding factors can be accounted for; the first during the experimental design, by achieving better experiment control (Johnson & Besselsen, 2002) over the entangled factors (better factor separation during grouping) and the second during statistical analysis, by ap-

plication of statistical methods to account for confounding and thus avoid related Type I errors. A technique applied during experimental design to isolate and, if necessary, eliminate variability due to extraneous causes (Everitt, 2007), and thus produce a better estimate of treatment effects, is termed (randomized) blocking (Damaraju, 2005; Festing & Altman, 2002). Under this design strategy, samples are divided in subgroups called blocks so that variability within blocks is less than variability between blocks. Multi-arrayed chips, like NimbleGen 12-well arrays, are especially useful to apply the randomized blocking technique. In the case of utilizing a one chip per sample- strategy, on chips with standardized placement of probes and with no (or minimal) replication of probe sets like Affymetrix MOE 133A2, HG-U95 or HG-U133 chips, it is impossible to separate array to array variability from sample to sample variability (Rao, 2009). Attempts to correct for confounded effects by statistical modeling alone reduce power of detection for true differential expression thus leading to increased rate of false-positive results in the confounded design. Proper normalization (see normalization) improves differential expression testing in both experiments (confounded or not) but randomization has been proven to be the most important fac-

Copyright 2012, IGI Global. Copying or distributing in print or electronic forms without written permission of IGI Global is prohibited.

International Journal of Systems Biology and Biomedical Technologies, 1(3), 1-39, July-September 2012 5

tor for establishing accurate results (Verdugo et al., 2009).

1.2. Choice of Microarray Platform

The choice of a microarray platform (Table 4, Microarray suppliers) should be based, apart from the cost, on the chip availability for the species under analysis, on genome coverage, the starting amount of RNA needed, quality of array manufacturing, the validity and availability of software tools for image analysis, the quality of gene annotation combined with assured company support in the future, and intra platform variability. Intra-platform variability and reproducibility have been used as measures of data quality (Yauk & Berndt, 2007). Experiments have been carried out to determine the effective differences in accuracy (proximity to true value) (de Reynies et al., 2006), sensitivity (ability to accurately detect changes at low concentrations), and specificity (to hybridize to the correct gene) among the technologies (Draghici, Khatri, Eklund, & Szallasi, 2006; Hardiman, 2004; van Bakel & Holstege, 2004).

1.3. Quality Controls

Quality controls have been established to ensure the quality of the sample both before and after hybridization and provide crucial information on whether to utilize or not a sample or an array for downstream analysis. Quality controls are divided into two broad categories; biological and software. The choice of the method to apply depends entirely on the step of the experiment. Biological quality controls, which are carried out prior to hybridization, aim at controlling the quality of the prepared RNA sample. Instruments like the Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer and Nanodrop spectrophotometer (NB: nanodrop can only check the quantity) offer users the ability to assess the quality and quantity of the RNA samples (Kiewe et al., 2009; Thompson & Hackett, 2008). Another measure of quality used at this step is the Frequency Of Incorporation (FOI). The FOI is a measure of the level of dye incorporation into a labeled nucleic acid sample. FOI measurements are important

to check labeling consistence, and to provide a guide as to how much probe is required for hybridization. FOI requires prior determination of DNA or RNA product yield and the amount of dye attached to it. The picomoles of dye present are calculated from the dyes extinction coefficient, and through this the FOI is determined (Promega Inc., 2012). Following hybridization, software quality controls come into play. This type of quality control is reliant on image analysis. In example control of the uniformity of the hybridization, e.g., border element control plots in the case of Affymetrix chips (Affymetrix Inc., 2004). Based on software quality controls, pre-filtering/ masking and/or background/signal adjustment are applied to edit out portions of the array image or balance intensities of areas with high or low signal. Masking refers to applications of microarray signal correction that account for cross hybridization (Naef, Lim, Patil, & Magnasco, 2002; Naef & Magnasco, 2003), array scratches, improper scanner configuration (Shi et al., 2005; Timlin, 2006), spot light saturation and washing issues (Yauk, Berndt, Williams, & Douglas, 2005) that may have occurred (Speed, 2003). Masking blocks the normalization algorithm from parsing signals of ruled out areas. A number of different DNA microarray platforms use spiked-in targets to check the performance of the sample preparation and hybridization.

1.4. Normalization

Normalization is performed to correct for systematic differences between samples on the same slide, or between slides, which do not represent true biological variation but are the result of biases introduced throughout the procedure. Normalization is fundamental for experiments to be combined and/or compared. It focuses on adjusting the individual hybridization intensities in order to balance them appropriately so that meaningful biological comparisons can be made (Quackenbush, 2002). Signal scaling factors are utilized for assessing the overall signal quality of the arrays. Apart from the

Copyright 2012, IGI Global. Copying or distributing in print or electronic forms without written permission of IGI Global is prohibited.

6 International Journal of Systems Biology and Biomedical Technologies, 1(3), 1-39, July-September 2012

low number of biological replicates, that can affect the strength of the statistical analysis, poor quality of chip construction influences negatively the analysis of differential expression. The signal is adjusted so that the estimated expression values will fall on proper scale. There are a number of reasons why data must be normalized: to remove systematic biases, which include sample preparation, variability in hybridization, spatial effects, scanner settings, experimenter bias (Mecham, Nelson, & Storey, 2010; Argyropoulos et al., 2006). The decision as to which normalization method is appropriate may depend on the biological nature of the dataset examined. For each microarray technology there is a preferred normalization method (Argyropoulos et al., 2006; Bolstad, Irizarry, Astrand, & Speed, 2003; Wu, Xing, Myers, Mian, & Bissell, 2005). Typical normalization methods include the global mean or median normalization (Bilban, Buehler, Head, Desoye, & Quaranta, 2002), rank invariant normalization (Tseng, Oh, Rohlin, Liao, & Wong, 2001), quantile (Bolstad et al., 2003), contrast (Astrand, 2003), LOWESS/LOESS methods (Cleveland, Grosse, & Shyu, 1991) and cyclic loess (Dudoit, Yang, Speed, & Callow, 2002). For many types of commercial arrays, R-Bioconductor (Team, 2008; Gentleman et al., 2004) packages can be used to do background adjustment and data normalization (Bolstad et al., 2003), including RMA (Robust MultiArray Average expression measure) (Irizarry et al., 2003), GCRMA (Robust Multi-Array Average expression measure using sequence information) (Wu, Irizarry, Gentleman, Martinez-Murillo, & Spencer, 2004), VSN (Variance Stabilization and Normalization) (Huber, von Heydebreck, Sultmann, Poustka, & Vingron, 2002) and Li and Wong (2001). Data from spike-in experiments, where the mRNA-ratios of a set of artificial clones are known, may be used to determine the relative merits of a set of analysis methods (Ryden et al., 2006).

manufacturing of many microarrays. Two color arrays suffer more from missing values in comparison to other microarray platforms (e.g., array scratches, scanner improper configuration, spot light saturation etc.) (Jornsten, Ouyang, & Wang, 2007). In case of opting for a platform that does have missing values innate to the array creation, one possible solution is to exclude whole slides that appear problematic. However, this solution is impractical since usually no slide is perfect and modern arrays contain tens of thousands of probes making measurements more sensitive to artifacts. Imputation of missing values (Donders, van der Heijden, Stijnen, & Moons, 2006) is best done either using many replicates within the same logical set (Jornsten et al., 2007) or by intra-chip probe replication (Du, 2010; Lin, Du, Huber, & Kibbe, 2008), especially helpful in case of custom built arrays (MYcroarray.com, 2011) .

1.6. Statistical Selection

Statistical selection is applied to identify the list of statistically significant differentially expressed genes, out of the total set of genes found on the arrays. Several statistical selection methods are currently available to test the hypothesis of a gene being differentially expressed. The two main categories are as follows: (i) the parametric tests, like t-test or ANOVA, for experiments that compare more than two factors at the same time (Cui & Churchill, 2003; Dudoit et al., 2002; Ideker, Thorsson, Siegel, & Hood, 2000; Kerr, Martin, & Churchill, 2000; Park et al., 2003) and (ii) the non-parametric tests, like Wilcoxon sign-rank and Kruskal-Wallis (Conover, 1980), which both can be applied to cDNA or oligonucleotide arrays (Affymetrix Inc.) (Tusher, Tibshirani, & Chu, 2001). These tests result in each gene being given a statistical significance score (p-value). A threshold is then applied to the score to determine, together with the fold change difference of each gene, the DEGs. A common problem with this approach is that while a strict p-value threshold would provide assurance on the statistical significance, many genes do not reach this threshold resulting in a limited number

1.5. Missing Values

Missing values are a serious issue for further concern innate to the technology behind the

Copyright 2012, IGI Global. Copying or distributing in print or electronic forms without written permission of IGI Global is prohibited.

International Journal of Systems Biology and Biomedical Technologies, 1(3), 1-39, July-September 2012 7

of statistical significant genes and even fewer DEGs; this is often due to few replicates being tested and the best decision is then to use Rank Products (Breitling, Armengaud, Amtmann, & Herzyk, 2004; Breitling & Herzyk, 2005). Another issue is the multiple comparisons problem. This means that with an increasingly high number of individual tests, the likelihood of data observation satisfying the acceptance criterion, by chance alone, is amplified. Methods to minimize this problem include the false discovery error rate (Benjamini & Hochberg, 1995; Efron & Tibshirani, 2002; Jung, 2005; Keselman, Cribbie, & Holland, 2002; Reiner et al., 2003; Shedden et al., 2005; Storey, 2002; Tibshirani, 2006; van den Oord & Sullivan, 2003; Yang, Yang, McIndoe, & She, 2003) and the Bonferroni corrections (Holm, 1979). The R library limma is considered to be the most widely utilized package for statistical selection of microarray analysis (Smyth, 2004), and is based on a linear modeling approach to fit microarray intensity data.

proven to lead to results of higher quality (Dai et al., 2005; Gautier, Moller, Friis-Hansen, & Knudsen, 2004; Sandberg & Larsson, 2007; Elo et al., 2005), better biological interpretation of the DEGs list, and has also aided the comparative analysis of datasets (Tzouvelekis et al., 2007) by providing an orthologuous genes map between species.

2. DATA-MINING: DERIVING BIOLOGICAL INFORMATION FROM MICROARRAY EXPERIMENTS

A successful primary analysis of a microarray experiment leads to a list of statistically significant DEGs. DNA microarray studies often implicate hundreds of genes in the pathogenesis of complex diseases, affecting many different mechanisms and pathways. How can such complexity be understood? How can hypotheses be formulated and tested? To extract the biological information from the lists of DEGs we need to apply methods to build or identify gene networks that interconnect the DEGs to common functions, biological pathways, regulatory elements, similarly expressed genes, existing literature, previous experimental data suggesting high specificity roles, mutation and disease related information. An updated list of links of software, currently available for the extraction of biological information, can be found at http://www.bioinformatics.gr (Leung, 2007; Paparountas, 2007).

1.7. Annotation

Annotation is required to proceed to data mining. Primary annotation uses X,Y map coordinates to link the position of the signal on the microarray surface to the probe ID (Affymetrix Inc.). At a second step, probe sequence associated annotation retrieval is achieved through reference databases (Draghici, Sellamuthu, & Khatri, 2006; Durinck et al., 2005; Haider et al., 2009; Smedley et al., 2009) (Table 6, Gene ID conversion). These steps produce information from the list of DEGs that will be used to extract knowledge through data mining (see data-mining). The importance of updating the annotation prior to data-mining cannot be stressed enough (Barbosa-Morais et al., 2010; Liu et al., 2007; Lu, Lee, Salit, & Cam, 2007; Sandberg & Larsson, 2007) the main reasons being that certain probes may be mis-targeting or deprecated, or new information, related to the biology behind the coded oligonucleotide sequence, may have been recently uncovered. Annotation update prior to data mining has

2.1. Clustering

As a first step of data mining, clustering analysis can help in the identification of gene expression patterns by providing a graphical representation of experimental data. Clustering analysis can be divided in two categories: (i) supervised and (ii) unsupervised. In a supervised approach, the classes (clusters) are predefined whereas in the unsupervised data, classes are unknown. It is common practice that clustering of microarray data, is performed after pre-processing of the

Copyright 2012, IGI Global. Copying or distributing in print or electronic forms without written permission of IGI Global is prohibited.

8 International Journal of Systems Biology and Biomedical Technologies, 1(3), 1-39, July-September 2012

data (normalize, filter, impute missing values and standardize) (Figure 2). Several clustering methods exist (Table 5, Clustering methods) (Yeung, Haynor, & Ruzzo, 2001). Clustering can be conducted per sample and per gene or by a combination of the two and it relies on direct comparison of gene expression (normalized intensity levels) to identify patterns of co-expression. Per gene clustering is especially useful as it provides organized data groups which are non-biased by a working hypothesis. It can be performed on the DEGs lists to identify common clusters of genes and differences between groups. The sublists-results of this method can fuel further data mining that will be presented in the following sections. Briefly, after retrieval of annotation related to the identified subgroups of genes, we can make hypothesis on genes function (e.g., same protein family or same cellular pathway), their transcriptional regulation (transcription regulatory factors, miRNA) and on genes with unknown function based on the role of the genes they co-cluster with (guilt by association) (Quackenbush, 2003; Stuart, Segal, Koller, & Kim, 2003; Wolfe, Kohane, & Butte, 2005). Clustering per sample is useful to identify sub-classification, for example to predict groups of patients, forming a primary indicator of condition outcome or treatments with inhibitors/small molecules.

A vs B type experimental design (Churchill, 2002) single Venn-diagram. The second step is applied when needed to cross compare multiple Venn-diagrams. This enables identification of common or unique traits between conditions i.e., common KEGG pathways or common transcription factors, even when the compared DEGs sets do not contain the same probes. A following step is the identification of the geneculprits behind the common traits.

2.2.1. Data-Mining Related to Relational Databases

In the relational databases, non-complex information is retrieved to provide basic information related to the genes, for example showing the common transcription factors binding domains present in the regulatory regions upstream the DEGs start sites, microRNA binding sites, etc. Here we provide methods that connect the genes to information related to their common regulatory elements (Tables 7 and 8) drug toxicity analysis (Table 9), mutation and disease (Table 9), existing literature (Table 10), functions (Table 11), biological pathways (Tables 11 and 12), similarly expressed genes (Table 12), previous experimental data suggesting high specificity roles, and similar protein products (Table 13). Furthermore we suggest integrative approaches that provide information based simultaneously on more than one category. It is important at all times to have a good understanding of what each tool does and the probability of error based on each separate error discovery procedure utilized (Gold, Miecznikowski, & Liu, 2009). 2.2.1.1. Transcription Factor Analysis & Motif Analysis Software Statistically significant genes or genes derived from the co-expression analysis are parsed through software that identifies common transcription factors - binding sites in upstream regions. By identifying transcription factors binding sites in common between the DEGs it is possible to formulate hypothesis on common gene control mechanisms (or in some cases hub

2.2. Knowledge Based Analysis

For this type of analysis, information stored in databases is retrieved and combined to support the formulation of a hypothesis, which describes the biological relation between the genes currently found in the DEGs list. This type of analysis combines annotation and functional analysis tools. The knowledge-based analysis can be a one or a two step approach, primarily depending on the design complexity of the experiment. The first step is to retrieve and combine information based on relational or semantic databases. This step is the maximum that may be applied to the

Copyright 2012, IGI Global. Copying or distributing in print or electronic forms without written permission of IGI Global is prohibited.

International Journal of Systems Biology and Biomedical Technologies, 1(3), 1-39, July-September 2012 9

Figure 2. Layout of the main experiment analysis, data-mining and meta-analysis procedures

genes), which might be responsible for gene co-regulation. Regulatory regions are generally conserved across species, and this principle has led to development of positional prediction tools (Pavlidis, Furey, Liberto, Haussler, & Grundy, 2001). Currently there is a plethora of available string search tools (Table 7, Transcription Factor and motif analysis) each with its own approach and true positive detection potency. 2.2.1.2. MicroRNA Discovery Software parsers may uncover common hidden binding sites of miRNAs (Lee, Feinbaum, & Ambros, 1993; Ruvkun, 2001). Each miRNA is processed from a primary transcript, known

as pri-miRNA, to a short stem-loop structure called pre-miRNA and finally to the functional miRNA. Experimentally derived miRNA sequences are often used as training sets in order to identify miRNA sequences across species with high evolutionary conservation. Some characteristic features are the stem-loop hairpin structure found on the pre-miRNAs, the conservation of sequence and secondary structure of the hairpin across species and also the clustering of miRNAs within close proximity to one another. A list of available search tools is provided (Table 8, miRNA) each utilizing its own database to search of common miRNAs.

Copyright 2012, IGI Global. Copying or distributing in print or electronic forms without written permission of IGI Global is prohibited.

10 International Journal of Systems Biology and Biomedical Technologies, 1(3), 1-39, July-September 2012

2.2.1.3. Drug Toxicity Analysis and Bioentity Analysis Specialized databanks for the identification of chemical substances that may target the identified genes or their products can be found by utilizing drug toxicity analysis tools (Table 9, Disease/Toxicity). The principle behind this method is to enrich gene lists with drugs or toxic agents that are known to affect the expression or the downstream regulation of the identified genes. This knowledge environment includes data derived from small molecules and smallmolecule screens, and resources for studying the data so that biological and medical insights can be gained. There are a number of different databanks that store an increasingly varied set of cell measurements derived from, among other biological objects, cell lines treated with small molecules. Pharmaceutical companies have their own databanks and analysis tools that allow the relationships between cell states, cell measurements and small molecules to be determined. Database access through commercial entities permit conditional utilization of such data. 2.2.1.4. Genetic Linkage Analysis Genetic linkage relates to genetic loci or alleles of genes that are inherited jointly. Genetic loci on the same chromosome are physically connected and tend to segregate together during meiosis. Maps of the genetically linked regions that show the position of known genes and/or genetic markers relative to each other in terms of recombination frequency, rather than as specific physical distance along each chromosome, are built in order to facilitate linkage mapping. This is critical for identifying the location of genes that cause genetic diseases. In an attempt to combine gene expression analysis with genetic linkage analysis, all differentially expressed genes are mapped to the chromosomes together with the known quantitative trait loci (QTL, chromosomal regions/genes segregating with a quantitative trait) (Aidinis et al., 2005; Tzouvelekis et al., 2007).

2.2.2. Semantic-Ontology Data Mining

Ontologies provide controlled vocabularies to describe concepts and relationships between them, thereby enabling knowledge sharing (Gruber, 1993). Utilization of information, stored in semantic-ontology databases, is considered as the second subtype of knowledge-based-datamining and facilitates the performance of a higher level search among the individual genes constituting the list of DEGs. This analysis is based on the theory that networks in nature are often characterized by a small number of highly connected nodes, while the majority of nodes have few connections. The highly connected nodes serve as hubs that affect many other nodes. The process identifies such hubs that have key roles in the network. In other words aims at annotating the results by reducing the complexity, so a large number of genes are transformed into a shorter list of biological themes (Larsson, Wennmalm, & Sandberg, 2006). Currently there are many such structured vocabularies (Jegga, 2006), used to represent biological entities and functions, each though is specialized in a certain field of biomedical science. OBO foundry is an initiative for the development of new biomedical ontologies that establishes the set of principles for ontology formation (Smith et al., 2007). OLS Ontology Lookup Service (Cote, Jones, Apweiler, & Hermjakob, 2006) (EBI) provides a web service interface to query multiple ontologies from a single location with a unified output format. BioPortal (http://bioportal.bioontology.org/) is a Web-based application for accessing and sharing biomedical ontologies. Three major types of ontology analysis are the (i) literature analysis, (ii) the functional analysis and (iii) the pathways analysis. 2.2.2.1. Literature Analysis It aims at finding associations between genes according to information found in the literature. The simplest way is to find the defined terms of search inside the literature by text-mining. An advancement of the method is to create gene

Copyright 2012, IGI Global. Copying or distributing in print or electronic forms without written permission of IGI Global is prohibited.

International Journal of Systems Biology and Biomedical Technologies, 1(3), 1-39, July-September 2012 11

networks based on the amount of times that this relationship has been referred in the literature (Table 10, Literature analysis software). Semantic approach of literature analysis is by utilizing the ontology related to the MeSH terminology of Medline repository. The MeSH vocabulary is a distinctive feature of the MEDLINE database produced by the United States National Library of Medicine. 2.2.2.2. Functional Analysis Functional analysis aims at storing information related to gene or gene products location, function and interaction. Functional analysis provides a biological interpretation for the data obtained from the primary analysis. A reference to the most often used tools is discussed in this paper. The most widely accepted method for functional analysis is based on Gene Ontology (GO) terms (Aidinis et al., 2005). The GO project (Ashburner et al., 2000) captures and organizes the increasing knowledge on gene properties into three controlled vocabularies describing a gene product in terms of its associated biological processes, cellular components and molecular functions in a species-independent manner. GO terms, enriched among a list of DEGs, can provide insight into the biological processes and provide a link between biological knowledge and either gene expression profiles or proteomics data (GO-Slim). Additionally, by using this technique it is possible to map GO terms and incorporate manual GO annotation into own databases to enhance a given dataset or to validate automated ways of deriving information about gene function (text-mining) (Table 11, Gene ontology analysis software). 2.2.2.3. Pathway Analysis This approach aims at identifying metabolic pathways which might be over-represented among members of a given gene list. One of the most commonly used resource for pathway enrichment analysis is the KEGG database (Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes) (Kanehisa, Goto, Kawashima, Okuno, & Hattori, 2004). Assessment as to whether a pathway

has been activated or not can be carried out in two ways: either by examining the ratio of the active genes divided by the total number of genes known for their role in that pathway, or by identifying whether certain pathways have statistically significant over-representation of active genes according to the results of the hypergeometric test. The additional ability to overlay gene expression details can significantly promote biological interpretation especially in kinetics based microarray experiments (Table 12, Pathway analysis software).

2.2.3. Integrative Data-Mining

Another approach to knowledge based analysis is to combine the findings of the two types mentioned above to produce results in a top down (minimal detailed information) or a bottom up approach (maximization of detailed combined information). 2.2.3.1. Gene Prioritization Gene prioritization is a process to identify and prioritize genes of interest, according to their similarity to a custom made list of genes, which is known a priori to be involved in a particular disease or phenotype. Currently two software suites excel in this field namely Endeavor (Aerts et al., 2006) and GeneWanderer (Kohler, Bauer, Horn, & Robinson, 2008). Endeavor uses a number of different data sources including both vocabulary-based (such as GO) as well as other data sources (such as BLAST and microarray databases). The ranking of a test gene for a given data source is calculated based on its similarity with the training genes, while the final prioritization is calculated based on order statistics of the individual rankings. GeneWanderer utilizes retrieved interaction data from major databases of protein interactions (HPRD, (Peri et al., 2004) BIND (Alfarano et al., 2005) and BioGrid (Stark et al., 2006), IntACT (Kerrien et al., 2007), and DIP (Salwinski et al., 2004) to create a protein-protein interaction (PPI) network. Gene prioritization is achieved by ranking each of the genes of interest according to (i) the relative position of a test gene to a training

Copyright 2012, IGI Global. Copying or distributing in print or electronic forms without written permission of IGI Global is prohibited.

12 International Journal of Systems Biology and Biomedical Technologies, 1(3), 1-39, July-September 2012

gene and (ii) the number of interactions of a test gene to different training genes. The main difference of the two suites is that Endeavour utilizes methods of shortest path and direct interaction that identify local properties to rank candidate genes, while GeneWanderer utilizes an algorithm for random walk or diffusion kernel that identifies global characteristics of the interaction network. 2.2.3.2. Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA) Genes of certain groups may be the controlling factors for phenotypes; still the individual genes of those groups may not be directly related to the phenotype under analysis. Gene groupings are made according to biological function, chromosomal location, or regulation. The advantages of this approach are two (i) GSEA provides a way to integrate multiple data-mining tests and (ii) apart from over-representation analysis it provides the option to take into account the expression levels of the DEGs list, so that a 10x expression will weigh more than a 2x expression after over representation analysis, which the current software for GO, miRNA, transcription factors analyses and pathways analyses do not provide. The main inhibiting factor for this kind of analysis is the non-controllable quality and the amount of information that is available for each individual gene, common problem in all data mining software, while a second one is the fact that GSEA does not integrate a wide variety of data sources. Characteristic software are (GSEA) (Subramanian et al., 2005), PAGE (Kim & Volsky, 2005) and GeneTrail (Backes et al., 2007). 2.2.3.3. Information Retrieval of Disease and Protein The retrieval of detailed gene information and related proteins/diseases at an early stage of the analysis, may lead to the formation of biological hypotheses that might influence downstream interpretation. This information can be utilized in order to better understand human biology, to predict potential disease risks, and to stimulate the development of new therapies to prevent and

treat these diseases. DNA microarray studies of gene-interaction networks of complex diseases may contain modules of co-regulated or interacting genes that have distinct biological functions. Such modules may be linked to specific gene polymorphisms, transcription factors, cellular functions and disease mechanisms. Genes that are reliably active only in the context of their modules can be considered markers for particular modules and may thus be promising candidates for biomarkers or therapeutic targets (Benson & Breitling, 2006). Diseases are often linked to proteins; therefore a better understanding of the protein interaction is essential. Protein-protein interactions are key determinants of protein function. Protein-protein interaction maps can serve as a suitable base to anchor genomics/gene expression, small interfering and microRNAs (siRNA/ miRNA), protein function and post-translational modifications, metabolic/signaling pathways and genetics/clinically-relevant information, as previously demonstrated by the maps generated for model organisms, such as H. Pylori (Rain et al., 2001), yeast (Uetz et al., 2000; Gavin et al., 2002; Han et al., 2004), C. elegans (Li et al., 2004), and Drosophila (Giot et al., 2003). These maps can represent an entire organism, a particular cell type or a tissue or an organ such as the mammalian brain (Choudhary & Grant, 2004) (Table 13, Protein-protein interactions).

3. META-ANALYSIS

Decisions about the validity of a hypothesis cannot be based on the results of a single study, due to intrinsic variability. Rather, a mechanism is needed to integrate data across studies. Meta-analysis is the statistical procedure for combining data from multiple studies. Meta-analysis aims to minimize systematic variations due to technical reasons such as lab effect and microarray platform, or biological factors such as circadic rhythm, the stress or species specific intricacies, while enabling recognition of real differences, and extraction of valid cross-experiment information. A first

Copyright 2012, IGI Global. Copying or distributing in print or electronic forms without written permission of IGI Global is prohibited.

International Journal of Systems Biology and Biomedical Technologies, 1(3), 1-39, July-September 2012 13

target of such analyses is the biological interpretation of a group of data; when the effect of a treatment is consistent from one study to the next, meta-analysis can be used to identify this common effect. When the effect varies from one study to the next, meta-analysis may be used to identify the reason for the variation. Apart from the biological interpretation of a group of data, the second target of a metaanalysis is biomarker identification. Biomarkers are genes which, when recognized as being selectively highly expressed in a pathological condition during a gene expression analysis, help in the direct recognition of diseases. The first rule governing a meta-analysis is the retrieval of datasets from databases containing high quality raw datasets. The retrieved datasets must be updated with the latest annotation, (same IDs and same build, preferably latest version) (Eszlinger, Krohn, Kukulska, Jarzab, & Paschke, 2007; Sandberg & Larsson, 2007). Furthermore the selected experiments should have good annotation that provide information about the datasets (metadata). Experimental metadata should include information about protocols, microarray platform, sample characteristics, and experimental design, including sample and data relationships. The availability of the raw data and metadata ensures the conduct of high quality analysis and is the primary concern behind the formulation of the MIAME (Brazma et al., 2001) standard. Compliance to the standard is required in order to facilitate the interpretation of the experimental results unambiguously and to potentially reproduce the experiment. The type of meta-analysis that we will be discussing produces a list of genes, that is either supported by the findings of the constitutive experiments or new hypotheses may be drawn based on further exploratory analysis. This list of genes (considered to be of higher quality in comparison to the individual constitutive experiments) can be thereafter fed into the data mining techniques, hence, providing the best way to create a complete statistically supported biological interpretation of the condition(s) under question.

A presentation of meta-analysis in reference to the dataset complexity and comparison models has been discussed in past studies (Larsson et al., 2006), while others (Yauk & Berndt, 2007) have reviewed the cross platform comparability of results. Comparative expression profiling is a way to exploit previously collected data in relation to the list of statistically significant genes. For this method the expression profiles of the genes of interest from past and current experiments are compared. In most cases the past study results are stored as flat files or in platformspecific databases, the most prominent among them being: GEO (Barrett et al., 2005) and ArrayExpress (Parkinson et al., 2005). Certain repositories databases T1D db (Hulbert et al., 2007), GEO (Barrett et al., 2005), and related database related tools (Adler et al., 2009; Kapushesky et al., 2010; Rhodes et al., 2007; Wu et al., 2009) provide the option to compare the normalized raw data of past experiments from the graphical user interface, which permits the direct comparison of expression levels across experiments, thus enabling basic comparative expression profiling analysis. Databases provide expression profiling over many experiments and organisms of specific genes, most often related to a certain disease or field of study (Table 14, Meta-analysis software).

3.1. Integrative Data-Mining and Meta-Analysis

The heterogeneous mix of data and information from the field of Genome Sciences includes functional descriptions of the DNA sequence, molecular interactions, images of molecules or phenotype of a microbe, plant or animal, and details about the environment in which these organisms live. The advent of the grid computing era has made holistic approaches to relate these data sources with high throughput biology technologies, such as microarray and next generation sequencing, achievable. Knowledgebases such as Facebase (Hochheiser et al., 2011) and KBase (Energy, 2010) are drawing near or have started producing actual

Copyright 2012, IGI Global. Copying or distributing in print or electronic forms without written permission of IGI Global is prohibited.

14 International Journal of Systems Biology and Biomedical Technologies, 1(3), 1-39, July-September 2012

Table 1. Summary points of article

Summary Points Microarray experiments may be flawed due to, non-optimal sample size, RNA/DNA quality and quantity, inefficient hybridization and normalization, ability to analyze the data. There is no global guide for microarray analysis. Data mining depends on the needs and requirements of each individual experiment Vast amount of microarray data and a number of different repositories are publicly available. We suggest software for each different aspect of biological information extraction, and combination of data across different datasets. The databases suggested in this paper can be utilized for biological information extraction from SNP, CGH, FISH, SAGE, RNA-Seq, Chip-Seq experiments.

results (Wolfson, 2008). The ultimate goal behind these multi-million dollar endeavors encompassing many fields of science is the predictive understanding of biological systems. The significant value of these projects is better recognized by (i) the development of freely available frameworks for software-database integration (The NCI Center for Bioinformatics, 2011; Hull et al., 2006; Oster et al., 2007) (ii) the hardware infrastructure to run analyses (Dinh, 2011; Fox, 2011; Halligan, Geiger, Vallejos, Greene, & Twigger, 2009; Kabachinski, 2011; Schatz, Langmead, & Salzberg, 2010) (iii) novel software tools (Blankenberg et al., 2010; Goecks, Nekrutenko, & Taylor, 2010) that are able to fully utilize the grid (iv) training of new scientists on cutting edge technology to further accelerate scientific research.

metabolic and microarray studies will lead to model changes throughout the system of the organism under question. Whole organism biology modeling could provide patients with individual customized medical treatment, which constitutes the scientific target in the field of systems biology. Summary points are listed in Table 1.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

Grateful acknowledgement for proofreading goes to Dr. Elisa Cesarini, Research Assistant at Istituto di Biologia Cellulare e Neurobiologia, CNR, Rome. This work was supported by the Hellenic Ministry for Development GSRTPENED-136 grant

4. CONCLUSION

The aforementioned techniques demonstrate the extent of the application of microarray technology. The introduction of the annotation based approaches in data mining and metaanalysis marks a tremendous leap forward, from discovery driven analysis to hypothesis driven analysis, indicative of the potential gene discoveries of the immediate future. The gathering of all information for each particular experiment forms a snapshot of information for the individual tissue/disease that the microarray experiment aims to analyze. Combination of individual experimental results of different

REFERENCES

Adler, P., Kolde, R., Kull, M., Tkachenko, A., Peterson, H., Reimand, J., & Vilo, J. (2009). Mining for coexpression across hundreds of datasets using novel rank aggregation and visualization methods. Genome Biology, 10(12), R139. doi:10.1186/gb2009-10-12-r139 Aerts, S., Lambrechts, D., Maity, S., Van Loo, P., Coessens, B., & De Smet, F. (2006). Gene prioritization through genomic data fusion. Nature Biotechnology, 24(5), 537544. doi:10.1038/nbt1203 Affymetrix Inc. (2004). Expression analysis technical manual. Retrieved from http://www.affymetrix.com/ support/technical/manual/expression_manual.affx

Copyright 2012, IGI Global. Copying or distributing in print or electronic forms without written permission of IGI Global is prohibited.

International Journal of Systems Biology and Biomedical Technologies, 1(3), 1-39, July-September 2012 15

Affymetrix Inc. (2006a). Affymetrix data analysis fundamentals. Retrieved from http://www.affymetrix.com/support/downloads/manuals/data_analysis_fundamentals_manual.pdf Affymetrix Inc. (2006b). Affymetrix NetAFFX. Retrieved from http://www.affymetrix.com/analysis/ index.affx Aidinis, V., Carninci, P., Armaka, M., Witke, W., Harokopos, V., & Pavelka, N. (2005). Cytoskeletal rearrangements in synovial fibroblasts as a novel pathophysiological determinant of modeled rheumatoid arthritis. PLOS Genetics, 1(4), e48. doi:10.1371/ journal.pgen.0010048 Al Moustafa, A. E., Alaoui-Jamali, M. A., Batist, G., Hernandez-Perez, M., Serruya, C., & Alpert, L. (2002). Identification of genes associated with head and neck carcinogenesis by cDNA microarray comparison between matched primary normal epithelial and squamous carcinoma cells. Oncogene, 21(17), 26342640. doi:10.1038/sj.onc.1205351 Alfarano, C., Andrade, C. E., Anthony, K., Bahroos, N., Bajec, M., & Bantoft, K. (2005). The biomolecular interaction network database and related tools 2005 update. Nucleic Acids Research, 33, 418424. doi:10.1093/nar/gki051 Allison, D. B., Cui, X., Page, G. P., & Sabripour, M. (2006). Microarray data analysis: From disarray to consolidation and consensus. Nature Reviews. Genetics, 7(1), 5565. doi:10.1038/nrg1749 Amundson, S. A., Myers, T. G., Scudiero, D., Kitada, S., Reed, J. C., & Fornace, A. J. Jr. (2000). An informatics approach identifying markers of chemosensitivity in human cancer cell lines. Cancer Research, 60(21), 61016110. Argyropoulos, C., Chatziioannou, A. A., Nikiforidis, G., Moustakas, A., Kollias, G., & Aidinis, V. (2006). Operational criteria for selecting a cDNA microarray data normalization algorithm. Oncology Reports, 15, 983996. Ashburner, M., Ball, C. A., Blake, J. A., Botstein, D., Butler, H., & Cherry, J. M. (2000). Gene ontology: Tool for the unification of biology. The gene ontology consortium. Nature Genetics, 25(1), 2529. doi:10.1038/75556 Astrand, M. (2003). Contrast normalization of oligonucleotide arrays. Journal of Computational Biology, 10(1), 95102. doi:10.1089/106652703763255697

Backes, C., Keller, A., Kuentzer, J., Kneissl, B., Comtesse, N., & Elnakady, Y. A. (2007). GeneTrail-Advanced gene set enrichment analysis. Nucleic Acids Research, 3, 186192. doi:10.1093/nar/gkm323 Baggerly, K. A., & Coombes, K. R. (2009). Deriving chemosensitivity from cell lines: Forensic bioinformatics and reproducible research in high-throughput biology. Ann. Appl. Stat., 3(4), 25. doi:10.1214/09AOAS291 Barbosa-Morais, N. L., Dunning, M. J., Samarajiwa, S. A., Darot, J. F., Ritchie, M. E., Lynch, A. G., & Tavare, S. (2010). A re-annotation pipeline for Illumina BeadArrays: Improving the interpretation of gene expression data. Nucleic Acids Research, 38(3), e17. doi:10.1093/nar/gkp942 Barnes, M., Freudenberg, J., Thompson, S., Aronow, B., & Pavlidis, P. (2005). Experimental comparison and cross-validation of the Affymetrix and Illumina gene expression analysis platforms. Nucleic Acids Research, 33(18), 59145923. doi:10.1093/nar/gki890 Barrett, T., Suzek, T. O., Troup, D. B., Wilhite, S. E., Ngau, W. C., & Ledoux, P. (2005). NCBI GEO: Mining millions of expression profiles--database and tools. Nucleic Acids Research, 33, 562566. doi:10.1093/nar/gki022 Benjamini, Y., & Hochberg, Y. (1995). Controlling the false discovery rate: A practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society. Series B. Methodological, 57, 11. Benson, M., & Breitling, R. (2006). Network theory to understand microarray studies of complex diseases. Current Molecular Medicine, 6(6), 695701. doi:10.2174/156652406778195044 Best, C. J., Leiva, I. M., Chuaqui, R. F., Gillespie, J. W., Duray, P. H., & Murgai, M. (2003). Molecular differentiation of high- and moderate-grade human prostate cancer by cDNA microarray analysis. Diagnostic Molecular Pathology, 12(2), 6370. doi:10.1097/00019606-200306000-00001 Bilban, M., Buehler, L. K., Head, S., Desoye, G., & Quaranta, V. (2002). Normalizing DNA microarray data. Current Issues in Molecular Biology, 4(2), 5764. Blankenberg, D., Von Kuster, G., Coraor, N., Ananda, G., Lazarus, R., & Mangan, M. Taylor, J. (2010). Galaxy: A web-based genome analysis tool for experimentalists. In F. M. Ausubel, R. Brent, R. E. Kingston, D. D. Moore, J. G. Seidman, J. A. Smith et al. (Eds.), Current protocols in molecular biology (Ch. 19, pp. 1-21). New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons.

Copyright 2012, IGI Global. Copying or distributing in print or electronic forms without written permission of IGI Global is prohibited.

16 International Journal of Systems Biology and Biomedical Technologies, 1(3), 1-39, July-September 2012

Bolstad, B. M., Irizarry, R. A., Astrand, M., & Speed, T. P. (2003). A comparison of normalization methods for high density oligonucleotide array data based on variance and bias. Bioinformatics (Oxford, England), 19(2), 185193. doi:10.1093/bioinformatics/19.2.185 Brazma, A., Hingamp, P., Quackenbush, J., Sherlock, G., Spellman, P., & Stoeckert, C. (2001). Minimum information about a microarray experiment (MIAME)-toward standards for microarray data. Nature Genetics, 29(4), 365371. doi:10.1038/ ng1201-365 Breitling, R., Armengaud, P., Amtmann, A., & Herzyk, P. (2004). Rank products: A simple, yet powerful, new method to detect differentially regulated genes in replicated microarray experiments. FEBS Letters, 573(1-3), 8392. doi:10.1016/j.febslet.2004.07.055 Breitling, R., & Herzyk, P. (2005). Rank-based methods as a non-parametric alternative of the T-statistic for the analysis of biological microarray data. Journal of Bioinformatics and Computational Biology, 3(5), 11711189. doi:10.1142/S0219720005001442 Choudhary, J., & Grant, S. G. (2004). Proteomics in postgenomic neuroscience: the end of the beginning. Nature Neuroscience, 7(5), 440445. doi:10.1038/ nn1240 Chuaqui, R. F., Bonner, R. F., Best, C. J., Gillespie, J. W., Flaig, M. J., & Hewitt, S. M. (2002). Post-analysis follow-up and validation of microarray experiments. Nature Genetics, 32, 509514. doi:10.1038/ng1034 Churchill, G. A. (2002). Fundamentals of experimental design for cDNA microarrays. Nature Genetics, 32, 490495. doi:10.1038/ng1031 Cleveland, W. S., Grosse, E., & Shyu, W. M. (1991). Local regression models. In Chambers, J. M., & Hastie, T. (Eds.), Statistical models in S (pp. 309376). New York, NY: Chapman & Hall. Conover, W. (1980). Practical nonparametric statistics. New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons. Coons, S. J. (2009). The FDAs critical path initiative: A brief introduction. Clinical Therapeutics, 31(11), 25722573. doi:10.1016/j.clinthera.2009.11.035 Cote, R. G., Jones, P., Apweiler, R., & Hermjakob, H. (2006). The ontology lookup service, a lightweight cross-platform tool for controlled vocabulary queries. BMC Bioinformatics, 7, 97. doi:10.1186/14712105-7-97

Cui, X., & Churchill, G. A. (2003). Statistical tests for differential expression in cDNA microarray experiments. Genome Biology, 4(4), 210. doi:10.1186/ gb-2003-4-4-210 Dagliyan, O., Uney-Yuksektepe, F., Kavakli, I. H., & Turkay, M. (2011). Optimization based tumor classification from microarray gene expression data. PLoS ONE, 6(2), e14579. doi:10.1371/journal. pone.0014579 Dai, M., Wang, P., Boyd, A. D., Kostov, G., Athey, B., & Jones, E. G. (2005). Evolving gene/transcript definitions significantly alter the interpretation of GeneChip data. Nucleic Acids Research, 33(20), e175. doi:10.1093/nar/gni179 Damaraju, R., & Lakshmi, V. P. (2005). Block designs: Analysis, combinatorics and applications. Singapore: World Scientific. Dan, S., Tsunoda, T., Kitahara, O., Yanagawa, R., Zembutsu, H., & Katagiri, T. (2002). An integrated database of chemosensitivity to 55 anticancer drugs and gene expression profiles of 39 human cancer cell lines. Cancer Research, 62(4), 11391147. de Reynies, A., Geromin, D., Cayuela, J. M., Petel, F., Dessen, P., Sigaux, F., & Rickman, D. S. (2006). Comparison of the latest commercial short and long oligonucleotide microarray technologies. BMC Genomics, 7, 51. doi:10.1186/1471-2164-7-51 Dinh, A. K. (2011). Cloud computing 101. Journal of American Health Information Management Association, 82(4), 3637, 44. Dobbin, K., & Simon, R. (2005). Sample size determination in microarray experiments for class comparison and prognostic classification. Biostatistics (Oxford, England), 6(1), 2738. doi:10.1093/ biostatistics/kxh015 Dobbin, K. K., Kawasaki, E. S., Petersen, D. W., & Simon, R. M. (2005). Characterizing dye bias in microarray experiments. Bioinformatics (Oxford, England), 21(10), 24302437. doi:10.1093/bioinformatics/bti378 Donders, A. R., van der Heijden, G. J., Stijnen, T., & Moons, K. G. (2006). Review: A gentle introduction to imputation of missing values. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 59(10), 10871091. doi:10.1016/j. jclinepi.2006.01.014 Draghici, S., Khatri, P., Eklund, A. C., & Szallasi, Z. (2006). Reliability and reproducibility issues in DNA microarray measurements. Trends in Genetics, 22(2), 101109. doi:10.1016/j.tig.2005.12.005

Copyright 2012, IGI Global. Copying or distributing in print or electronic forms without written permission of IGI Global is prohibited.

International Journal of Systems Biology and Biomedical Technologies, 1(3), 1-39, July-September 2012 17

Draghici, S., Sellamuthu, S., & Khatri, P. (2006). Babels tower revisited: A universal resource for cross-referencing across annotation databases. Bioinformatics (Oxford, England), 22(23), 29342939. doi:10.1093/bioinformatics/btl372 Du, P. (2010). Preprocess Affymetrix data by integrating VST with RMA method (Version lumi v. 1.8.3). Retrieved from http://svitsrv25.epfl.ch/R-doc/ library/lumi/html/affyVstRma.html Dudoit, S., Yang, Y. H., Speed, T., & Callow, M. J. (2002). Statistical methods for identifying differentially expressed genes in replicated cDNA microarray experiments. Statistica Sinica, 12, 18. Dupuy, A., & Simon, R. M. (2007). Critical review of published microarray studies for cancer outcome and guidelines on statistical analysis and reporting. Journal of the National Cancer Institute, 99(2), 147157. doi:10.1093/jnci/djk018 Durinck, S., Moreau, Y., Kasprzyk, A., Davis, S., De Moor, B., Brazma, A., & Huber, W. (2005). BioMart and Bioconductor: A powerful link between biological databases and microarray data analysis. Bioinformatics (Oxford, England), 21(16), 34393440. doi:10.1093/bioinformatics/bti525 Efron, B., & Tibshirani, R. (2002). Empirical Bayes methods and false discovery rates for microarrays. Genetic Epidemiology, 23(1), 7086. doi:10.1002/ gepi.1124 Elo, L. L., Lahti, L., Skottman, H., Kylaniemi, M., Lahesmaa, R., & Aittokallio, T. (2005). Integrating probe-level expression changes across generations of Affymetrix arrays. Nucleic Acids Research, 33(22), e193. doi:10.1093/nar/gni193 Eszlinger, M., Krohn, K., Kukulska, A., Jarzab, B., & Paschke, R. (2007). Perspectives and limitations of microarray-based gene expression profiling of thyroid tumors. Endocrine Reviews, 28(3), 322338. doi:10.1210/er.2006-0047 Everitt, B. S. (2007). Medical statistics from A to Z: A guide for clinicians and medical students (2nd ed.). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. Faul, F., Erdfelder, E., Buchner, A., & Lang, A. G. (2009). Statistical power analyses using G*Power 3.1: Tests for correlation and regression analyses. Behavior Research Methods, 41(4), 11491160. doi:10.3758/BRM.41.4.1149

Faul, F., Erdfelder, E., Lang, A. G., & Buchner, A. (2007). G*Power 3: A flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behavior Research Methods, 39(2), 175191. doi:10.3758/BF03193146 Festing, M. F., & Altman, D. G. (2002). Guidelines for the design and statistical analysis of experiments using laboratory animals. The Institute for Laboratory Animal Research Journal, 43(4), 244258. Fodor, S. P., Read, J. L., Pirrung, M. C., Stryer, L., Lu, A. T., & Solas, D. (1991). Light-directed, spatially addressable parallel chemical synthesis. Science, 251(4995), 767773. doi:10.1126/science.1990438 Fox, A. (2011). Computer science. Cloud computing-whats in it for me as a scientist? Science, 331(6016), 406407. doi:10.1126/science.1198981 Futschik, M. E., Sullivan, M., Reeve, A., & Kasabov, N. (2003). Prediction of clinical behaviour and treatment for cancers. Applied Bioinformatics, 2(3), 5358. Gautier, L., Moller, M., Friis-Hansen, L., & Knudsen, S. (2004). Alternative mapping of probes to genes for Affymetrix chips. BMC Bioinformatics, 5, 111. doi:10.1186/1471-2105-5-111 Gavin, A. C., Bosche, M., Krause, R., Grandi, P., Marzioch, M., & Bauer, A. (2002). Functional organization of the yeast proteome by systematic analysis of protein complexes. Nature, 415(6868), 141147. doi:10.1038/415141a Gentleman, R. C., Carey, V. J., Bates, D. M., Bolstad, B., Dettling, M., & Dudoit, S. (2004). Bioconductor: Open software development for computational biology and bioinformatics. Genome Biology, 5(10), R80. doi:10.1186/gb-2004-5-10-r80 Giot, L., Bader, J. S., Brouwer, C., Chaudhuri, A., Kuang, B., & Li, Y. (2003). A protein interaction map of Drosophila melanogaster. Science, 302(5651), 17271736. doi:10.1126/science.1090289 Goecks, J., Nekrutenko, A., & Taylor, J. (2010). Galaxy: A comprehensive approach for supporting accessible, reproducible, and transparent computational research in the life sciences. Genome Biology, 11(8), R86. doi:10.1186/gb-2010-11-8-r86 Gold, D. L., Miecznikowski, J. C., & Liu, S. (2009). Error control variability in pathway-based microarray analysis. Bioinformatics (Oxford, England), 25(17), 22162221. doi:10.1093/bioinformatics/btp385

Copyright 2012, IGI Global. Copying or distributing in print or electronic forms without written permission of IGI Global is prohibited.

18 International Journal of Systems Biology and Biomedical Technologies, 1(3), 1-39, July-September 2012

Gruber, T. R. (1993). A translation approach to portable ontology specifications. Knowledge Acquisition, 5(2), 2. doi:10.1006/knac.1993.1008 Haider, S., Ballester, B., Smedley, D., Zhang, J., Rice, P., & Kasprzyk, A. (2009). BioMart Central Portal--unified access to biological data. Nucleic Acids Research, 37, 2327. doi:10.1093/nar/gkp265 Halligan, B. D., Geiger, J. F., Vallejos, A. K., Greene, A. S., & Twigger, S. N. (2009). Low cost, scalable proteomics data analysis using Amazons cloud computing services and open source search algorithms. Journal of Proteome Research, 8(6), 31483153. doi:10.1021/pr800970z Han, J. D., Bertin, N., Hao, T., Goldberg, D. S., Berriz, G. F., & Zhang, L. V. (2004). Evidence for dynamically organized modularity in the yeast protein-protein interaction network. Nature, 430(6995), 8893. doi:10.1038/nature02555 Hardiman, G. (2004). Microarray platforms--comparisons and contrasts. Pharmacogenomics, 5(5), 487502. doi:10.1517/14622416.5.5.487 Hochheiser, H., Aronow, B. J., Artinger, K., Beaty, T. H., Brinkley, J. F., & Chai, Y. (2011). The FaceBase Consortium: A comprehensive program to facilitate craniofacial research. Developmental Biology, 355(2), 175182. doi:10.1016/j.ydbio.2011.02.033 Holm, S. (1979). A simple sequentially rejective Bonferroni test procedure. Scandinavian Journal of Statistics, 6, 6570. Huber, W., von Heydebreck, A., Sultmann, H., Poustka, A., & Vingron, M. (2002). Variance stabilization applied to microarray data calibration and to the quantification of differential expression. Bioinformatics (Oxford, England), 18(1), 96104. doi:10.1093/bioinformatics/18.suppl_1.S96 Hulbert, E. M., Smink, L. J., Adlem, E. C., Allen, J. E., Burdick, D. B., & Burren, O. S. (2007). T1DBase: Integration and presentation of complex data for type 1 diabetes research. Nucleic Acids Research, 35(1), 742746. doi:10.1093/nar/gkl933 Hull, D., Wolstencroft, K., Stevens, R., Goble, C., Pocock, M. R., Li, P., & Oinn, T. (2006). Taverna: A tool for building and running workflows of services. Nucleic Acids Research, 34, 729732. doi:10.1093/ nar/gkl320 Ideker, T., Thorsson, V., Siegel, A. F., & Hood, L. E. (2000). Testing for differentially-expressed genes by maximum-likelihood analysis of microarray data. Journal of Computational Biology, 7(6), 805817. doi:10.1089/10665270050514945

Ikeda, T., Jinno, H., & Shirane, M. (2007). Chemosensitivity-related genes of breast cancer detected by DNA microarray. Anticancer Research, 27(4C), 26492655. Ioannidis, J. P., Allison, D. B., Ball, C. A., Coulibaly, I., Cui, X., & Culhane, A. C. (2009). Repeatability of published microarray gene expression analyses. Nature Genetics, 41(2), 149155. doi:10.1038/ng.295 Irizarry, R. A., Hobbs, B., Collin, F., Beazer-Barclay, Y. D., Antonellis, K. J., Scherf, U., & Speed, T. P. (2003). Exploration, normalization, and summaries of high density oligonucleotide array probe level data. Biostatistics (Oxford, England), 4(2), 249264. doi:10.1093/biostatistics/4.2.249 Irizarry, R. A., Warren, D., Spencer, F., Kim, I. F., Biswal, S., & Frank, B. C. (2005). Multiple-laboratory comparison of microarray platforms. Nature Methods, 2(5), 345350. doi:10.1038/nmeth756 Jegga, A. (2006). Bio-Ontologies: A list of links. Retrieved from http://anil.cchmc.org/Bio-Ontologies. html Johnson, P. D., & Besselsen, D. G. (2002). Practical aspects of experimental design in animal research. The Institute for Laboratory Animal Research Journal, 43(4), 202206. Jornsten, R., Ouyang, M., & Wang, H. Y. (2007). A meta-data based method for DNA microarray imputation. BMC Bioinformatics, 8, 109. doi:10.1186/14712105-8-109 Jung, S. H. (2005). Sample size for FDR-control in microarray data analysis. Bioinformatics (Oxford, England), 21(14), 30973104. doi:10.1093/bioinformatics/bti456 Kabachinski, J. (2011). Whats the forecast for cloud computing in healthcare? Biomedical Instrumentation & Technology, 45(2), 146150. doi:10.2345/0899-8205-45.2.146 Kanehisa, M. (1995). KEGG: Kyoto encyclopedia of genes and genomes. Kyoto, Japan: Kanehisa Laboratories. doi:10.1093/nar/28.1.27 Kanehisa, M., Goto, S., Kawashima, S., Okuno, Y., & Hattori, M. (2004). The KEGG resource for deciphering the genome. Nucleic Acids Research, 32, 277280. doi:10.1093/nar/gkh063 Kapushesky, M., Emam, I., Holloway, E., Kurnosov, P., Zorin, A., & Malone, J. (2010). Gene expression atlas at the European bioinformatics institute. Nucleic Acids Research, 38, 690698. doi:10.1093/ nar/gkp936

Copyright 2012, IGI Global. Copying or distributing in print or electronic forms without written permission of IGI Global is prohibited.

International Journal of Systems Biology and Biomedical Technologies, 1(3), 1-39, July-September 2012 19

Kerr, M. K., Martin, M., & Churchill, G. A. (2000). Analysis of variance for gene expression microarray data. Journal of Computational Biology, 7(6), 819837. doi:10.1089/10665270050514954 Kerrien, S., Alam-Faruque, Y., Aranda, B., Bancarz, I., Bridge, A., & Derow, C. (2007). IntActopen source resource for molecular interaction data. Nucleic Acids Research, 35, 561565. doi:10.1093/ nar/gkl958 Keselman, H. J., Cribbie, R., & Holland, B. (2002). Controlling the rate of Type I error over a large set of statistical tests. The British Journal of Mathematical and Statistical Psychology, 55(1), 2739. doi:10.1348/000711002159680 Kiewe, P., Gueller, S., Komor, M., Stroux, A., Thiel, E., & Hofmann, W. K. (2009). Prediction of qualitative outcome of oligonucleotide microarray hybridization by measurement of RNA integrity using the 2100 Bioanalyzer capillary electrophoresis system. Annals of Hematology, 88(12), 11771183. doi:10.1007/s00277-009-0751-5 Kikuchi, T., Daigo, Y., Katagiri, T., Tsunoda, T., Okada, K., & Kakiuchi, S. (2003). Expression profiles of non-small cell lung cancers on cDNA microarrays: identification of genes for prediction of lymph-node metastasis and sensitivity to anti-cancer drugs. Oncogene, 22(14). Kim, J. M., Sohn, H. Y., Yoon, S. Y., Oh, J. H., Yang, J. O., Kim, J. H.,Kim, N. S. (2005). Identification of gastric cancer-related genes using a cDNA microarray containing novel expressed sequence tags expressed in gastric cancer cells. Clinical Cancer Research, 11(2). Kim, S. Y., & Volsky, D. J. (2005). PAGE: Parametric analysis of gene set enrichment. BMC Bioinformatics, 6, 144. Kitchen, R. R., Sabine, V. S., Simen, A. A., Dixon, J. M., Bartlett, J. M., & Sims, A. H. (2011). Relative impact of key sources of systematic noise in Affymetrix and Illumina gene-expression microarray experiments. BMC Genomics, 12, 589. doi:10.1186/1471-2164-12-589 Kohler, S., Bauer, S., Horn, D., & Robinson, P. N. (2008). Walking the interactome for prioritization of candidate disease genes. American Journal of Human Genetics, 82(4), 949958. doi:10.1016/j. ajhg.2008.02.013

Lancaster, J. M., Dressman, H. K., Clarke, J. P., Sayer, R. A., Martino, M. A., & Cragun, J. M. (2006). Identification of genes associated with ovarian cancer metastasis using microarray expression analysis. International Journal of Gynecological Cancer, 16(5), 17331745. doi:10.1111/j.1525-1438.2006.00660.x Larsson, O., Wennmalm, K., & Sandberg, R. (2006). Comparative microarray analysis. OMICS: A Journal of Integrative Biology, 10(3), 381397. doi:10.1089/ omi.2006.10.381 Lee, R. C., Feinbaum, R. L., & Ambros, V. (1993). The C. elegans heterochronic gene lin-4 encodes small RNAs with antisense complementarity to lin-14. Cell, 75(5), 843854. doi:10.1016/00928674(93)90529-Y Lee, Z.-J., Lin, S. W., Hsu, C.-C. V., & Huang, Y.P. (2006, November 14-17). Gene extraction and identification tumor/cancer for microarray data of ovarian cancer. In Proceedings of the IEEE Region 10 Conference (pp. 1-3). Leung, Y. F. (2007). Functional genomics. Retrieved from http://genomicshome.com/ Li, C., & Hung Wong, W. (2001). Model-based analysis of oligonucleotide arrays: Model validation, design issues and standard error application. Genome Biology, 2(8), Li, S., Armstrong, C. M., Bertin, N., Ge, H., Milstein, S., Boxem, M.,Vidal, M. (2004). A map of the interactome network of the metazoan C. elegans. Science, 303(5657), 540543. doi:10.1126/science.1091403 Lin, S. M., Du, P., Huber, W., & Kibbe, W. A. (2008). Model-based variance-stabilizing transformation for Illumina microarray data. Nucleic Acids Research, 36(2), e11. doi:10.1093/nar/gkm1075 Liu, H., Li, J., & Wong, L. (2005). Use of extreme patient samples for outcome prediction from gene expression data. Bioinformatics (Oxford, England), 21(16), 33773384. doi:10.1093/bioinformatics/ bti544 Liu, H., Zeeberg, B. R., Qu, G., Koru, A. G., Ferrucci, A., & Kahn, A. (2007). AffyProbeMiner: A web resource for computing or retrieving accurately redefined Affymetrix probe sets. Bioinformatics (Oxford, England), 23(18), 23852390. doi:10.1093/ bioinformatics/btm360 Lu, J., Lee, J. C., Salit, M. L., & Cam, M. C. (2007). Transcript-based redefinition of grouped oligonucleotide probe sets using AceView: High-resolution annotation for microarrays. BMC Bioinformatics, 8, 108. doi:10.1186/1471-2105-8-108

Copyright 2012, IGI Global. Copying or distributing in print or electronic forms without written permission of IGI Global is prohibited.

20 International Journal of Systems Biology and Biomedical Technologies, 1(3), 1-39, July-September 2012