Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

Overview On The Ven Bhikkhu Bodhi S Critique of A Note On Paticcasamuppada Ven Mettiko

Enviado por

katificationDescrição original:

Título original

Direitos autorais

Formatos disponíveis

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Overview On The Ven Bhikkhu Bodhi S Critique of A Note On Paticcasamuppada Ven Mettiko

Enviado por

katificationDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Overview on the Ven.

Bhikkhu Bodhi's Critique of 'A Note on Paticcasamuppada'

Written by Ven. Mettiko Translated extract from 'Kritik' by Mettiko Bhikkhu: Notizen zu Dhamma, und andere Schriften: Germany, Verlag Beyerlein & Steinschule, 2007)

Shortly after the appearance of the [German] article 'Paiccasamuppdaeine alternative Annherung' in Lotusbltter, the author received a whole series of consensual posts and emails. There was only one censorious reaction, an exposed person associated with the 'Deutsche Buddhistische Union', which dubbed the author as a 'cultural neo-colonialist' and was indignant about the defiance of the venerable tradition. A content-related discussion did not take place. Likewise, Ven. avra was mostly confronted with incomprehension and not so much with refusal during his lifetime. He waited in vain for a profound critique. He surely had been glad about A Critical Examination of avra Thera's 'A Note on Paiccasamuppda' of the American monk-scholar Bhikkhu Bodhi, a critique which was written shortly after the appearance of Clearing the Path, and therefore much earlier than the copyright seems to imply: London, Buddhist Studies Review 1998. Bhikkhu Bodhi was ordained in 1972 in Sri Lanka, where he spent more than 20 years. He was president and editor of the Buddhist Publication Society, cotranslator of The Middle Lenght Discourses of the Buddha (Majjhima Nikya) and translator of The Connected Discourses of the Buddha (Sayutta Nikya). Today he lives in the Bodhi Monastery, New Jersey. Interestingly enough he was an admirer of Ven. avra in his first two years of his life as a monk, but then turned away because, amongst other things, of an 'arrogant attitude' of the Notes (email from 30 September 2005). He writes: When I came in contact with the deeply humble, unselfish, sympathetic, open-minded personality of the Ven. Nanaponika ... that was an entirely different world. But that doesn't mean that I have lost my appreciation for the Ven. avra as a thinker. I find many of his formulations highly insightful, even brilliant, and leave open the possibility that he might really have attained the first path and the first fruition. I'm not qualified to decide this question, but I think it is possible that individual stream-enterers may interpret the Buddhist teachings conceptually wrong. Bhikkhu Bodhi's polemic paper and apologia is more extensive than the criticized Note itself and would take a disproportional amount of space in this book. Nevertheless it shall be responded in bullet point form. On the one hand the Ven.

avra rates lack of knowledge of the commentary tradition admittedly as advantage (see Preface (a)), on the other hand he adduces good reasons to deal with false teachings (Letter 91). That's of course not to say that the writing of Bhikkhu Bodhi falls in the second category, but his Critique is definitely a touchstone on which one can measure one's understanding of the Notes. So that is to say that the reading of the Critique is recommended when one is somewhat firm in the existential approach to the Buddha's Teachings. [...] In the introduction Bhikkhu Bodhi describes with almost disbelieving astonishment the impact and approach of the Notes: For twenty-two years this [of Notes on Dhamma] circulated from hand to hand among a small circle of readers in the form of typed copies, photocopies, and handwritten manuscripts. Only in 1987 did Notes on Dhamma appear in print. [...] But in spite of its limited availability, Clearing the Path has had an impact on its readers that has been nothing short of electric. Promoted solely by word of mouth, the book has spawned an international network of admirersa Theravda Buddhist underground united in their conviction that Notes on Dhamma is the sole key to unlock the inner meaning of the Buddhas Teaching [...] Few of the standard interpretative principles upheld by Theravda orthodoxy are spared the slashing of his pen. The most time-honoured explanatory tools for interpreting the Suttas [...]all come in for criticism. (Para. 1) Bhikkhu Bodhi wonders in Para. 2: Strangely, although Notes on Dhamma makes such a sharp frontal attack on Theravda orthodoxy, to date no proponent of the mainstream Theravda tradition has risen to the occasion and attempted to counter its arguments. Ven. Bodhi wants to fill this gap by taking on the Note on Paiccasamuppda which is a 'bold challenge to the prevailing three-life interpretation'. Like the Ven. avra, he thereby wants to accept only the four main Nikays and the older parts of the Khuddaka Nikya as last resort. He concedes that the commentarial description is not to be found in the Suttas in all its particulars but serves as an instrument to make the Suttas and the Abhidhamma compatible. Neither is it necessary to accept it in all its particulars. His concern is only the 'essential vision' which underlies it, 'namely, that the twelvefold formula of [paiccasamuppda] extends over three lives and as such describes the generative structure of sasra, the round of repeated births.' (Para. 3) Bhikkhu Bodhi is 'aghast' over the fact that Ven. avra opposes an interpretation which is there for such a long time yet'virtually from the time that tradition emerged as a distinct school' and which is already to be found in the 'Vibhaga of the Abhidhamma Piaka and the Patisambhidamagga of the Sutta Piaka' (which he excludes two paragraphs earlier as last resort). After a half page of consternation, that someone stands alone against 'the entire mainstream Buddhist philosophical tradition' (incl. Sarvastivada, Mahasanghika, the great Madhyamika philosopher Nagarjuna along with the current Mahyna schools) he turns to the topic of the Buddha's Teachings: dukkha, the existential problem.

Here the differences already loom up between Ven. avra's subjective, existential approach and Bhikkhu Bodhi's scholastic, objective approachby Bhikkhu Bodhi's inability to understand dukkha as 'existential fear', 'nor even the distorted sense of self of which such anxiety may be symptomatic' (Para. 5). For him dukkha is the 'bondage to sasarathe round of recurring births, ageing and death' and 'self' is apparently only a special, additional (optional?) problem. From this it follows that (explicit in Para. 6) dukkha ends because and when one is no longer reborn. The personal, subjective problem of suffering becomes scholastically and scientifically objectivatedwonderful illustrative material for Ven. avra's criticism on the 'would-be synthesis of public facts' (compare Preface (c), (f), RPA and others). That nibbna thereby comes out not as the end of subjectivity, but effectively as annihilation is inevitable: positivism by its own rules can only be 'transcended' with nihilism. If dukkha is understood as a fact (without the inclusion of the suffering, appropriating subject), as an objective fact, observable from outside, then one can imagine the 'end of dukkha'' only in form of the absence of rebirth, when the arahat is truly dead once and for all. In this context the editor wants to point out that not only 'death' is not applicable to the 'dead' arahat but also 'sickness' is not applicable to the 'living' arahat. Luang Pu Lah Khemapatto, one of the great realised masters of Thailand, which the editor was allowed to become acquainted with shortly before his 'falling apart of the body', was an impressing example that having a 'wreck of a body' doesn't have to mean 'sickness' or 'suffering'if no subject comes into play which regards this wreck as 'mine'. That the arahat doesn't suffer from 'death'see ADDITIONAL TEXTS 13 and A NOTE ON PAICCASAMUPPDA (b). One sign of the incompatibility of the two paradigms is the fact that for the most part Bhikkhu Bodhi uses the same Sutta passages as Ven. avra Thera to support his position (e.g. D.15, M.44, S.12.2 and others). Now to some details: The Critique begins with the topic 'birth' and assumes that Ven. avra says in the end that bhavapaccay jarmaraa, 'with being as condition ageing-&-death' instead of 'with birth as condition ageing-&-death'. That is of course only justified if one assumes that paiccasamuppda is a temporal process. The Ven. Bodhi criticizes that Ven. avra sees birth, ageing and death in relation to the 'self, whereas the Suttas talk about the birth, ageing and death of the body' (Para. 7). To see a contradiction between the two really means reducing 'self' to a 'phenomenon of purely grammatical interest' (Preface (b)). And: jti means re-birth after all (at least implicitly). As a proof Bhikkhu Bodhi regards the fact that according to the Suttas birth happens in different classes of existence (Para. 7 and 8). On the subject of sakhra nothing else remains to be done for the Ven. Bodhi than to unwrap again the commentarial gimmicks, which were mentioned and refused by Ven. avrathe diverse variants of the patchwork rug strategy ('here it means this, there it means that'): a) In relation with paiccasamuppda sakhra be identical with cetan. For lack of proof in the Suttas the 'Suttanta Bhajaniya section of its Paiccasamuppda Vibhaga of the Abhidhamma Piaka' must serve as authority, which after all 'can

make a cogent claim to antiquity'. (Para. 12) b) Sometimes sakhra means 'that which forms' (paiccasamuppda, 4. khandha), sometimes 'that which is formed' (two of the three marks of existence) and sometimes both (the triad in M.44 is a 1:2 mixed calculation). c) Manosakhra be identical with cittasakhra. Besides of some 'implicit' evidence on page 17 Bhikkhu Bodhi brings in passages in which manosakhra is about action and its fruit. He thereby overlooks that Ven. avra doesn't deny at all that there will be rebirth for a being which still has desire, and he writes in A NOTE ON PAICCASAMUPPDA (g) that manosakhra is action (which happens according to the conditions of the puthujjanathat is paiccasamuppda anuloma (15)). When I look through rose-coloured glasses, all temporal events are rosecoloured, but the glasses themselves are extra-temporal in relation to the viewed events. On the subject of sakhra the Ven. Bodhi makes a side-trip to the SHORTER NOTES of the same name. For him it is a 'cryptical message' that Ven. avra Thera regards the properties of king Mahasudassana as conditions (sakhra) for his identity (along the lines of 'clothes makes people'). Does he think that the Buddha made that speech of almost two hours to tell nanda that all properties of a universal monarch (complete with horse, elephant, [primary] wife) are conditioned things and as such impermanent? Is not Dgha 17, as a long-winded prelude to a platitude, degraded to a mere entertainment program thereby? Bhikkhu Bodhi can't follow Ven. avra's remarks, his lack of understanding is based on an entirely different point of view. So it's not a surprise that he fails to capture the twofold function of sakhra (specific and general) which is shown in 15, 20 and 21 of that Note. Also based on those different paradigms are of course dissensions in translating, e.g. when Bhikkhu Bodhi's translation of paibaddha (he sees as 'dependent on' rather than 'associated with') is achieved only due to the anticipation of the result. He rightly writes that Ven. avra Thera translates the word upaga mistakenly as past participle instead of present ('has arrived at', here correct as 'arriving'). But: The meaning of the sentence is not changed. The meaning of upaga does indeed change when Bhikkhu Bodhi falsely interprets the prefix upawith his 'goes on towards'upa- means 'here, here towards me (approaching me), related to me' (compare Hecker, Lesewrterbuch). It would be possible to bring in many other examples for the approach of the Critique, but they all run with the same already demonstrated pattern. Perhaps in short on Bhikkhu Bodhi's 'defence of the tradition' (from Para. 21). He circumvents the problem with vipkavedan (3) in the three-livesinterpretation by presenting a 'softer interpretation', 'although the Commentaries do take the hard line'. The soft of that variant is: the body be kammavipka, but at the same time the instrument which makes possible to feel vedan, which is not kammavipka. On 4 he bluntly denies the relation of the Sutta passage cited by Ven. avra

with paiccasamuppda and accuses him of 'strangely careless misreading of the passage'. avra recommends with a good reason to study this Sutta 'firsthand'. Bhikkhu Bodhi at least concedes that 'paiccasamuppda is introduced later in the Sutta'. In the discourse, after the headline 'Which, bhikkhus is the teaching proclaimed by me?', all four categories are shown (the 'activity of the mind' mentioned by Ven. avra in third place, paiccasamuppda as an explanation of the 2 nd and 3 rd Noble Truth in the fourth position). Unmistakable the Buddha afterwards explains the relation of the four categories. To assume that he teaches incoherently, this is indeed 'strange and careless'. Bhikkhu Bodhi solves his contradiction with vipkacetan elegantly by saying that nmarpa 'that descends into the womb is the result of past kamma, hence vipka' and by referring again to a commentaryAtthasalini, p. 87-88. He discounts Ven. avra's point that the three-lives-interpretation is not aklika: The examination of the Suttas on paiccasamuppda that we have undertaken above has confirmed that the usual twelve-term formula applies to a succession of lives. This conclusion must take priority over all deductive arguments against temporal succession in paiccasamuppda [...] Realization of the characteristic of anatta removes clinging, and with the elimination of clinging anxiety is removed, including existential anxiety over our inevitable aging and death. This, however, is not the situation being described by the PS formula... (Para. 24) Besides that Bhikkhu Bodhi explains wordy that according to the commentaries the paiccasamuppda formular is 'not a rigid series', no 'linear sequence', that 'ignorance, craving, and clinging in unison generate renewed becoming' etc., maybe in order to show that the three-lives-interpretation is somehow a bit aklika after all, and that definitely no seeing of former or future lives is necessary to see paiccasamuppda. (Para. 25) That paiccasamuppda shall be aklika would rely anyway on a wrong interpretation by Ven. avra, who assumes in an unfunded way that paiccasamuppda is included in the Dhamma which is described as aklika. (Para. 26). One could only wonder how Bhikkhu Bodhi ignores Suttas like Majjhima 26 where paiccasamuppda is mentioned virtually as the quintessence of the Buddhadhamma. And one wonders that one page later he allows paiccasamuppda as aklika again, butand his reasoning extends over five pagesit doesn't mean timelessness, but just that one sees the Dhamma immediately when one sees it. Bhikkhu Bodhi had intended to show exactly the errors in a 'thicket of errors' (of the Note on Paiccasamuppda). He succeeded! The Noteslike the author himself concedes in letter 76are full of errorslooked at from the traditional point of view. This point of view and the existential approach remain incompatible, however much arguments may be exchanged. Which point of view one wants to join is and will be 'a matter of one's fundamental attitude to one's own existence' (A NOTE ON PAICCASAMUPPDA 7). From Bhikkhu Bodhi's Critique it becomes clearer over and over again that from the commentarial point of view an understanding of the existential approach is

utterly out of the question. Syncretism ('Maybe both are right.''It's all the same anyway.') is totally discardedalone for this lesson it's worth to deal with his writing. However even this standpoint is a matter of standpoint as Bhikkhu Bodhi's email from 30 September 2005 shows: I'm not sure whether a syncretistic approach to the twelve link formular of Dependent Origination is impossible. I think the Ven. avra was a bit hasty to exclude this possibility, maybe in order to provoce. I don't believe that both approaches can be equally correct. [...] But I think that the interpretation of the Ven. avra provides an interesting and intellectually stimulating attempt to contribute an interpretation which is meaningful and attractive in the sense of contemporary existential and agnostic frameworks of thought. This interpretation could therefore act as 'skilful means' to indroduce people to the Dhamma which initially would hesitate to accept the teaching of rebirth. [...] Such a conciliation of both approaches [...] would of course seem a heresy to a later follower of him. Would this strategy go well? First to thrust the Notes in the hands of a sceptic or agnostic in the hope that afterwards he will take pleasure in the intellectual dry food of Visuddhimagga and Co.?

Você também pode gostar

- The Buddha's Path of Virtue A Translation of the DhammapadaNo EverandThe Buddha's Path of Virtue A Translation of the DhammapadaAinda não há avaliações

- A Critical Examination of Nyanavira Thera Bodhi BSR1998Documento28 páginasA Critical Examination of Nyanavira Thera Bodhi BSR1998katificationAinda não há avaliações

- On The Problem of The External World in The Ch'eng Wei Shih LunDocumento66 páginasOn The Problem of The External World in The Ch'eng Wei Shih Lunahwah78Ainda não há avaliações

- The Buddha's Path of Virtue: A Translation of the DhammapadaNo EverandThe Buddha's Path of Virtue: A Translation of the DhammapadaAinda não há avaliações

- Gethin Bhavanga and Rebirth 1994-With-Cover-Page-V2Documento26 páginasGethin Bhavanga and Rebirth 1994-With-Cover-Page-V2buddhiAinda não há avaliações

- The Bhagavata Purana: Sacred Text and Living TraditionNo EverandThe Bhagavata Purana: Sacred Text and Living TraditionNota: 2 de 5 estrelas2/5 (1)

- "There Is No Self" (Nâtmâsti) - Marek MejorDocumento24 páginas"There Is No Self" (Nâtmâsti) - Marek Mejoramnotaname4522Ainda não há avaliações

- The Nidnasamyukta and The Mlamadhyamakakrik: Understanding The Middle Way Through Comparison and ExegesisDocumento39 páginasThe Nidnasamyukta and The Mlamadhyamakakrik: Understanding The Middle Way Through Comparison and ExegesisMattia SalviniAinda não há avaliações

- Controvesies On The Origine of AbbhidhammaDocumento8 páginasControvesies On The Origine of AbbhidhammaHoang NguyenAinda não há avaliações

- Book Report Kalupahana Principles of Buddhist PsychologyDocumento20 páginasBook Report Kalupahana Principles of Buddhist PsychologyAudwin WilkinsonAinda não há avaliações

- Ambedkar On GitaDocumento22 páginasAmbedkar On GitaAnushriBhatnagarAinda não há avaliações

- Rethinking Non Self A New Perspective FR PDFDocumento21 páginasRethinking Non Self A New Perspective FR PDFCAinda não há avaliações

- A Note On The Caraka Samhita and BuddhismDocumento6 páginasA Note On The Caraka Samhita and BuddhismJigdrel77Ainda não há avaliações

- The Buddha Counsels A Theist.81161309Documento14 páginasThe Buddha Counsels A Theist.81161309Mia WallisAinda não há avaliações

- 8649 8457 1 PBDocumento20 páginas8649 8457 1 PBunespgAinda não há avaliações

- Buddhist Existentialism explores early Buddhist philosophyDocumento8 páginasBuddhist Existentialism explores early Buddhist philosophyGertjan MulderAinda não há avaliações

- Reviews of Books 3 7 3 The Two Traditions of Meditation in Ancient India - by Johannes Bronkhorst. (AltDocumento3 páginasReviews of Books 3 7 3 The Two Traditions of Meditation in Ancient India - by Johannes Bronkhorst. (Altcheng yangAinda não há avaliações

- Ambedkar On The GitaDocumento19 páginasAmbedkar On The GitaAlan MellerAinda não há avaliações

- Compassion in Schopenhauer and Śāntideva: Journal of Buddhist EthicsDocumento30 páginasCompassion in Schopenhauer and Śāntideva: Journal of Buddhist Ethicscata_banusAinda não há avaliações

- Buddhist and Freudian PsychologyDocumento5 páginasBuddhist and Freudian PsychologyhannahjiAinda não há avaliações

- The Bodhisatta's Practice of Breath Retention: Self-Mortification or An Advanced Meditative Technique?Documento21 páginasThe Bodhisatta's Practice of Breath Retention: Self-Mortification or An Advanced Meditative Technique?MuraliAinda não há avaliações

- Was The Buddha OmniscientDocumento11 páginasWas The Buddha Omniscientmyatchitshin4121Ainda não há avaliações

- Verhaeghen, Paul (2017) The Self-Effacing Buddhist No (T) - Self in Early Buddhism and Contemplative NeuroscienceDocumento17 páginasVerhaeghen, Paul (2017) The Self-Effacing Buddhist No (T) - Self in Early Buddhism and Contemplative NeuroscienceAnonymous QTvWm9UERAinda não há avaliações

- Utpaladeva's Lost Vivrti On The Ishwara Pratyabhijna Karika - Raffaele TorellaDocumento12 páginasUtpaladeva's Lost Vivrti On The Ishwara Pratyabhijna Karika - Raffaele Torellaraffaeletorella100% (1)

- 1.8 Tevijja S d13 Piya Proto11Documento31 páginas1.8 Tevijja S d13 Piya Proto11Sora LeeAinda não há avaliações

- Dimock MayaDocumento16 páginasDimock MayaanudasAinda não há avaliações

- Analayo - A Brief Criticism of The Two Paths To Liberation Theory PDFDocumento14 páginasAnalayo - A Brief Criticism of The Two Paths To Liberation Theory PDFWuAinda não há avaliações

- Tibetan Buddhism in Western Perspective (Herbert v. Guenther)Documento6 páginasTibetan Buddhism in Western Perspective (Herbert v. Guenther)hannahjiAinda não há avaliações

- LOY The Deconstruction of BuddhismDocumento23 páginasLOY The Deconstruction of BuddhismIain CowieAinda não há avaliações

- Origin and Evolution of the Theravada AbhidhammaDocumento9 páginasOrigin and Evolution of the Theravada AbhidhammaPemarathanaHapathgamuwaAinda não há avaliações

- Problem of External World in Cheng-Wei-shih-lun - SchmithausenDocumento63 páginasProblem of External World in Cheng-Wei-shih-lun - SchmithausenkokyoAinda não há avaliações

- Bodhi - Root-Of-Existance (Mulaparyaya-Sutta)Documento106 páginasBodhi - Root-Of-Existance (Mulaparyaya-Sutta)Shreyas PAI GAinda não há avaliações

- Seeds of Emptiness in Early Buddhist TextsDocumento8 páginasSeeds of Emptiness in Early Buddhist Textsjaojaotai taitaiAinda não há avaliações

- Thomas Jones MPhil DissertationDocumento83 páginasThomas Jones MPhil DissertationThomas JonesAinda não há avaliações

- Analayo - The Luminous MindDocumento42 páginasAnalayo - The Luminous MindWuAinda não há avaliações

- Buddhist IllogicDocumento234 páginasBuddhist IllogicAvi SionAinda não há avaliações

- Notes On The Bhagavad GitaDocumento47 páginasNotes On The Bhagavad GitaAnonymous 0ha8TmAinda não há avaliações

- Tony Page - Affirmation of Eternal Self in The Mahāyāna Mahaparinirvana SutraDocumento9 páginasTony Page - Affirmation of Eternal Self in The Mahāyāna Mahaparinirvana SutraAni LupascuAinda não há avaliações

- 2018 Reich BhattanayakaandVedantaInfluenceonSanskritLiteraryTheoryDocumento26 páginas2018 Reich BhattanayakaandVedantaInfluenceonSanskritLiteraryTheorybrizendineAinda não há avaliações

- Patanjali and The Buddhists - Johannes BronkhorstDocumento7 páginasPatanjali and The Buddhists - Johannes BronkhorstLangravio Faustomaria PanattoniAinda não há avaliações

- Awynne 2004 JiabsDocumento32 páginasAwynne 2004 Jiabskspalmo100% (1)

- Rebirth and Inbetween States - Ajahn SujatoDocumento10 páginasRebirth and Inbetween States - Ajahn SujatoDhamma ThoughtAinda não há avaliações

- The Meaning of Vairocana in Hua-Yen BuddhismDocumento14 páginasThe Meaning of Vairocana in Hua-Yen BuddhismKohSH100% (1)

- Buddha and GodDocumento26 páginasBuddha and Goda-c-t-i-o-n_acioAinda não há avaliações

- Yogacara Analysis of VijnanaDocumento17 páginasYogacara Analysis of VijnanaDarie NicolaeAinda não há avaliações

- Expansion of Buddhism Into Southeast Asia 0Documento22 páginasExpansion of Buddhism Into Southeast Asia 0Harits Harifan AlfikriAinda não há avaliações

- The Silence of The Buddha and Its Madhyamic InterpretationDocumento15 páginasThe Silence of The Buddha and Its Madhyamic Interpretationcrizna1100% (1)

- Is The Buddha Like A Man in The Street Dharmakīrti's AnswerDocumento31 páginasIs The Buddha Like A Man in The Street Dharmakīrti's AnsweryogacaraAinda não há avaliações

- Kathavatthu and VijnanakayaDocumento4 páginasKathavatthu and Vijnanakayacha072Ainda não há avaliações

- Ananda Coomaraswamy - Review of Paul Mus' BarabudurDocumento9 páginasAnanda Coomaraswamy - Review of Paul Mus' BarabudurManasAinda não há avaliações

- The Heretic SageDocumento20 páginasThe Heretic SageRicky SimmsAinda não há avaliações

- Paccekabuddha: A Buddhist AsceticDocumento43 páginasPaccekabuddha: A Buddhist AsceticBuddhist Publication Society100% (1)

- Confusing The Esoteric With The ExotericDocumento64 páginasConfusing The Esoteric With The ExotericSivasonAinda não há avaliações

- Birgit Kellner Yogacara Vijnanavada - Idealism Fenomenology o Ninguno - 34p PDFDocumento34 páginasBirgit Kellner Yogacara Vijnanavada - Idealism Fenomenology o Ninguno - 34p PDFFilosofia2018Ainda não há avaliações

- The Genesis of The Five Aggregate TeachingDocumento26 páginasThe Genesis of The Five Aggregate Teachingcrizna1Ainda não há avaliações

- Review-LUSTHAUS Buddhist Phenomenology H-BuddhismDocumento23 páginasReview-LUSTHAUS Buddhist Phenomenology H-Buddhismzhigp100% (1)

- Kodera DogenDocumento26 páginasKodera Dogenzdenek.bernardAinda não há avaliações

- Heart Sutra A Chinese ForgeryDocumento108 páginasHeart Sutra A Chinese ForgerykatificationAinda não há avaliações

- An Annotated Translation of The Madhyamakahrdayakarika-Tarkajvala (Missing V 55-68)Documento170 páginasAn Annotated Translation of The Madhyamakahrdayakarika-Tarkajvala (Missing V 55-68)Guhyaprajñāmitra3100% (3)

- Peace Codes Ebook SampleDocumento45 páginasPeace Codes Ebook Samplekatification100% (1)

- BasicsDocumento1 páginaBasicskatificationAinda não há avaliações

- E001 Pathwork Guide Lecture No.1 by Eva Broch PierrakosDocumento5 páginasE001 Pathwork Guide Lecture No.1 by Eva Broch Pierrakosstarborn777Ainda não há avaliações

- Intoduction PermacultureDocumento155 páginasIntoduction Permacultureyolandamandujano100% (3)

- Notes On DODocumento1 páginaNotes On DOkatificationAinda não há avaliações

- The Inner Bhagavad Geeta NotebooksDocumento86 páginasThe Inner Bhagavad Geeta Notebooksdholt777100% (1)

- GrapefruitDocumento22 páginasGrapefruitkatification100% (5)

- Still Flowing Water - Ajahn ChahDocumento121 páginasStill Flowing Water - Ajahn ChahpancakhandaAinda não há avaliações

- Mindful Communication-How To Speak and Hear The TruthDocumento6 páginasMindful Communication-How To Speak and Hear The TruthkatificationAinda não há avaliações

- Sri Nisargadatta Maharaj - I Am UnbornDocumento130 páginasSri Nisargadatta Maharaj - I Am UnbornMisterE23Ainda não há avaliações

- Pablo Neruda Keeping QuietDocumento1 páginaPablo Neruda Keeping QuietkatificationAinda não há avaliações

- SZC MMC Winter 2010Documento32 páginasSZC MMC Winter 2010katificationAinda não há avaliações

- Mind 2.0 Buddhist Methods For Upgrading The Mind - S Performance 0613aDocumento17 páginasMind 2.0 Buddhist Methods For Upgrading The Mind - S Performance 0613akatification100% (2)

- Heart Sutra GuideDocumento5 páginasHeart Sutra GuidekatificationAinda não há avaliações

- The Sacred Fire PT 1Documento101 páginasThe Sacred Fire PT 1BrimmingInBedlam100% (2)

- Clearing The Path Writings of Nanavira Thera 2up A4 Print VersionDocumento294 páginasClearing The Path Writings of Nanavira Thera 2up A4 Print VersionkatificationAinda não há avaliações

- Heart Sutra GuideDocumento5 páginasHeart Sutra GuidekatificationAinda não há avaliações

- Four Quartets - T.s.elliotDocumento53 páginasFour Quartets - T.s.elliotFoniortodoksonkoritsas ZeriiorthodhoksevekorçareAinda não há avaliações

- Enjoy Life All LifeDocumento10 páginasEnjoy Life All LifekatificationAinda não há avaliações

- Heart Sutra A Chinese ForgeryDocumento108 páginasHeart Sutra A Chinese ForgerykatificationAinda não há avaliações

- BirksLectures 2011Documento1 páginaBirksLectures 2011katificationAinda não há avaliações

- Tir Na NogDocumento57 páginasTir Na NogkatificationAinda não há avaliações

- Ayurvedic Guide To Healthy KidsDocumento9 páginasAyurvedic Guide To Healthy KidskatificationAinda não há avaliações

- The Master and His Emissary by McGilchristDocumento17 páginasThe Master and His Emissary by McGilchristkatification100% (1)

- Notes On DODocumento1 páginaNotes On DOkatificationAinda não há avaliações

- Pablo Neruda Keeping QuietDocumento1 páginaPablo Neruda Keeping QuietkatificationAinda não há avaliações

- Fire SermonDocumento3 páginasFire SermonkatificationAinda não há avaliações

- Foam On The Waves: Stephen FulderDocumento2 páginasFoam On The Waves: Stephen FulderkatificationAinda não há avaliações

- Bahiya SuttaDocumento3 páginasBahiya SuttakatificationAinda não há avaliações

- NozzelsDocumento47 páginasNozzelsraghu.entrepreneurAinda não há avaliações

- Touchstone 2nd 2-WB - RemovedDocumento8 páginasTouchstone 2nd 2-WB - RemovedMia JamAinda não há avaliações

- Huawei Routing Overview CommandDocumento26 páginasHuawei Routing Overview Commandeijasahamed100% (1)

- Presentation on William Stafford's poem "Travelling Through the DarkDocumento14 páginasPresentation on William Stafford's poem "Travelling Through the DarkRG RAJAinda não há avaliações

- Ramadan PlannerDocumento31 páginasRamadan Plannermurodovafotima60Ainda não há avaliações

- Oracle BI Suite EE 10g R3 Create Reports and Dashboards SummaryDocumento3 páginasOracle BI Suite EE 10g R3 Create Reports and Dashboards SummaryLakmali Wijayakoon0% (1)

- Sai Krishna: Summary of QualificationDocumento2 páginasSai Krishna: Summary of Qualificationsai KrishnaAinda não há avaliações

- Assignment C++ (MUHAMMAD RYMI BIN MOHD RAFIZAL)Documento6 páginasAssignment C++ (MUHAMMAD RYMI BIN MOHD RAFIZAL)MUHAMMAD RYMIAinda não há avaliações

- Developing The Assessment Instrument of SpeakingDocumento11 páginasDeveloping The Assessment Instrument of Speakingifdol pentagenAinda não há avaliações

- Second Language Identities by Block DDocumento5 páginasSecond Language Identities by Block Dkawther achourAinda não há avaliações

- दक्षिणामूर्तिस्तोत्र अथवा दक्षिणापुर्त्यष्टकम्Documento19 páginasदक्षिणामूर्तिस्तोत्र अथवा दक्षिणापुर्त्यष्टकम्AnnaAinda não há avaliações

- IT Certification Made Easy with ServiceNow Practice TestsDocumento93 páginasIT Certification Made Easy with ServiceNow Practice TestsGabriel Ribeiro GonçalvesAinda não há avaliações

- CTK-500 Electronic Keyboard Specs & DiagramsDocumento21 páginasCTK-500 Electronic Keyboard Specs & DiagramsdarwinAinda não há avaliações

- Project 3Documento30 páginasProject 3Aown ShahAinda não há avaliações

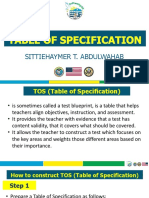

- Constructing a TOSDocumento17 páginasConstructing a TOSHymerAinda não há avaliações

- Question Bank: Course On Computer ConceptsDocumento18 páginasQuestion Bank: Course On Computer ConceptsVelocis Eduaction MallAinda não há avaliações

- Edgar Dale'S: Cone of ExperienceDocumento22 páginasEdgar Dale'S: Cone of Experienceapi-511492365Ainda não há avaliações

- The Technical Proposal and The Request of ProposalDocumento24 páginasThe Technical Proposal and The Request of ProposalMahathir Upao50% (2)

- Wa0009.Documento14 páginasWa0009.prasenajita2618Ainda não há avaliações

- English Result Intermediate Teacher's Book IntroductionDocumento9 páginasEnglish Result Intermediate Teacher's Book IntroductionomarAinda não há avaliações

- Reading Trends Improving Reading Skills MalaysaDocumento12 páginasReading Trends Improving Reading Skills MalaysaAnna Michael AbdullahAinda não há avaliações

- CE246 Practical List Database Management SystemDocumento27 páginasCE246 Practical List Database Management SystemnooneAinda não há avaliações

- Coherence Cohesion 1 1Documento36 páginasCoherence Cohesion 1 1Shaine MalunjaoAinda não há avaliações

- 2022 2023 Courseoutline Architectural Analysis and CriticismDocumento8 páginas2022 2023 Courseoutline Architectural Analysis and CriticismNancy Al-Assaf, PhDAinda não há avaliações

- Radiant International School, Patna: Split-Up Syllabus For Session 2019-2020Documento4 páginasRadiant International School, Patna: Split-Up Syllabus For Session 2019-2020KelAinda não há avaliações

- English Practice Book 4Documento19 páginasEnglish Practice Book 4akilasrivatsavAinda não há avaliações

- Jannah's Workbook (Final Requirement in English 6) (Repaired)Documento27 páginasJannah's Workbook (Final Requirement in English 6) (Repaired)JannahAinda não há avaliações

- How To Create A Lock FolderDocumento2 páginasHow To Create A Lock FolderChakshu GuptaAinda não há avaliações

- NY Test PrepDocumento75 páginasNY Test PrepYianniAinda não há avaliações

- Simple, Positive Language in Technical WritingDocumento3 páginasSimple, Positive Language in Technical Writingroel pugataAinda não há avaliações