Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

Macasiray Vs People

Enviado por

Kaye GeesDescrição original:

Título original

Direitos autorais

Formatos disponíveis

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Macasiray Vs People

Enviado por

Kaye GeesDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

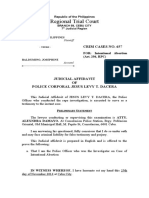

MACASIRAY VS PEOPLE G.R. No. 94736. June 26, 1998 MENDOZA, J.

: FACTS: Petitioners Melecio Macasiray, Virgilio Gonzales, and Benedicto Gonzales are the accused in Criminal Case No. 33(86) of the Regional Trial Court of San Jose City, presided over by Judge Pedro C. Ladignon. The case is for the murder of Johnny Villanueva, husband of private respondent Rosalina Rivera Villanueva, on February 9, 1986. It appears that in the course of the trial of the case, the prosecution introduced in evidence, as Exhibit B, an extrajudicial confession executed by petitioner Benedicto Gonzales on March 27, 1986, in which he admitted participation in the crime and implicated petitioners Melecio Macasiray and Virgilio Gonzales, his co-accused. Also presented in evidence, as Exhibit D, was the transcript of stenographic notes taken during the preliminary investigation of the case on April 8, 1986 before the fiscals office. This transcript contained statements allegedly given by Benedicto in answer to questions of the fiscal, in which he affirmed the contents of his extrajudicial confession. When the extrajudicial confession was offered at the conclusion of the presentation of evidence for the prosecution, petitioners objected to its admissibility on the ground that it was given without the assistance of counsel. The transcript of the preliminary investigation proceeding was similarly objected to on the same ground. In its order dated April 14, 1988, the trial court sustained the objections and declared the two documents to be inadmissible. It appears that when it was the turn of the defense to present evidence, Gonzales was asked about his extrajudicial confession (Exh. B). On cross-examination, he was questioned not only about his extrajudicial confession but also about answers allegedly given by him during the preliminary investigation and recorded in the transcript of the proceeding. As he denied the contents of both documents, the prosecution presented them as rebuttal evidence, allegedly to impeach the credibility of Gonzales. Petitioners once more objected and the trial court again denied admission to the documents. (Order, dated Oct. 17, 1988) Private respondent then sought the nullification of the trial courts orders and succeeded. The Court of Appeals declared the two documents admissible in evidence and ordered the trial court to admit them. Hence, this petition for review of the appellate courts decision. ISSUE: Whether or not petitioners waived objection to the admissibility of the documents, either by failing to object to their introduction during the trial or by using them in evidence RULING: First. Objection to evidence must be made after the evidence is formally offered.[4] In the case of documentary evidence, offer is made after all the witnesses of the party making the offer have testified,[5] specifying the purpose for which the evidence is being offered. [6] It is only at this time, and not at any other, that objection to the documentary evidence may be made. In this case, petitioners objected to the admissibility of the documents when they were formally offered. Contrary to the ruling of the appellate court, petitioners did not waive objection to admissibility of the said documents by their failure to object when these were marked, identified, and then introduced during the trial. That was not the proper time to make the objection. Objection to the documentary evidence must be made at the time it is formally offered, not earlier. Thus, it has been held that the identification of the document before it is marked as an exhibit does not constitute the formal offer of the document as evidence for the party presenting it. Objection to the identification and marking of the document is not equivalent to objection to the document when it is formally offered in evidence. What really matters is the objection to the document at the time it is formally offered as an exhibit. It may be mentioned in this connection that in one case, objection to the admissibility of a confession on the ground that no meaningful warning of his constitutional rights was given to the accused was raised as soon as the prosecution began introducing the confession, and the trial

judge sustained the objection and right away excluded the confession. This Court, through Chief Justice Fernando, upheld the action of the trial court over the dissent of Justice Aquino, who argued that the trial courts ruling was premature, considering that the confession was merely being identified. It was not yet being formally offered in evidence.[10] On the other hand, Justice Barredo, concurring, while agreeing that objection to documentary evidence should be made at the time of formal offer, nonetheless thought that to faithfully carry out the constitutional mandate, objections based on the Miranda right to counsel at the stage of police interrogation should be raised as early as possible and the ruling on such objections made just as soon in order not to create prejudice in the judge, in the event the confession is found inadmissible. [11] But the ruling in that case does not detract from the fact that objections should be made at the stage of formal offer. Objections to the admissibility of documents may be raised during trial and the court may rule on them then, but, if this is not done, the party should make the objections when the documentary evidence is formally offered at the conclusion of the presentation of evidence for the other party. Indeed, before it was offered in evidence, the confession in this case cannot even be considered as evidence to which the accused should object. Second. Nor is it correct to say that the confession was introduced in evidence by Benedicto Gonzales himself when it was his turn to present evidence for the defense. What happened is that despite the fact that in its order of April 14, 1988 the court sustained the objection to the admissibility of the confession and the statements given by Benedicto Gonzales at the preliminary investigation, the defense nonetheless asked him questions regarding his confession in reference to his denial of liability. It was thus not for the purpose of using as evidence the confession and the alleged statements in the preliminary investigation but precisely for the purpose of denying their contents that Gonzales was asked questions. Gonzales denied he ever gave the answers attributed to him in the TSN allegedly taken during the preliminary investigation. The defense did not really have to ask Gonzales questions regarding his confession inasmuch as the court had already declared both the confession and the transcript of stenographic notes to be inadmissible in evidence, but certainly the defense should not be penalized for exercising an abundance of caution. In fact, the defense did not mark the confession as one of its exhibits, which is proof of the fact that it did not adopt it as evidence. There is, therefore, no basis for the appellate courts ruling that because the defense adopted the confession by introducing it in evidence, the defense waived any objection to the admission of the same in evidence.

Você também pode gostar

- Macasiray Vs PeopleDocumento2 páginasMacasiray Vs PeopleRia Kriselle Francia PabaleAinda não há avaliações

- 01 People v. ServanoDocumento7 páginas01 People v. ServanoJet SiangAinda não há avaliações

- 3-L PP Vs SanchezDocumento2 páginas3-L PP Vs SanchezShaine Aira ArellanoAinda não há avaliações

- People vs. Sumili Presumption of Innocence in Drugs CasesDocumento5 páginasPeople vs. Sumili Presumption of Innocence in Drugs CasesChaAinda não há avaliações

- 60 Nissan North Edsa vs. United Philippine Scout Veterans Detective and Protective AgencyDocumento1 página60 Nissan North Edsa vs. United Philippine Scout Veterans Detective and Protective AgencyMitchi Barranco100% (1)

- Republic Vs de Guzman 652 SCRA 101, GR 175021 (June 15, 2011)Documento10 páginasRepublic Vs de Guzman 652 SCRA 101, GR 175021 (June 15, 2011)Lu CasAinda não há avaliações

- CD-59.Feria Vs CADocumento4 páginasCD-59.Feria Vs CABingoheartAinda não há avaliações

- People V CamatDocumento2 páginasPeople V CamatRachel Leachon0% (1)

- Loida M. Javier vs. Pepito GonzalesDocumento2 páginasLoida M. Javier vs. Pepito GonzalesAreeya ManalastasAinda não há avaliações

- TUASON v. CA, 241 SCRADocumento14 páginasTUASON v. CA, 241 SCRAEmil BautistaAinda não há avaliações

- Nissan North Edsa Vs United DigestDocumento1 páginaNissan North Edsa Vs United DigestJr CosteloAinda não há avaliações

- People v. MayingqueDocumento2 páginasPeople v. MayingqueTootsie GuzmaAinda não há avaliações

- 3 - People v. SamontanezDocumento1 página3 - People v. SamontanezRonnie Garcia Del RosarioAinda não há avaliações

- Madrigal v. CA DigestDocumento2 páginasMadrigal v. CA DigestFrancis Guinoo100% (1)

- Magdayao v. PeopleDocumento1 páginaMagdayao v. PeopleRomela Eleria GasesAinda não há avaliações

- 114020-2002-People v. NorrudinDocumento14 páginas114020-2002-People v. NorrudinMau AntallanAinda não há avaliações

- PP v. Palanas - Case DigestDocumento2 páginasPP v. Palanas - Case DigestshezeharadeyahoocomAinda não há avaliações

- Damaso Ambray and Ceferino Ambray Jr. vs. Sylvia Tsourous Et. Al. G.R. No. 209264 July 5 2016Documento2 páginasDamaso Ambray and Ceferino Ambray Jr. vs. Sylvia Tsourous Et. Al. G.R. No. 209264 July 5 2016Xtian HernandezAinda não há avaliações

- FERIA Vs CADocumento1 páginaFERIA Vs CAWeng CuevillasAinda não há avaliações

- JUDICIAL NOTICE Habagat Grill v. DMC Urban DeveloperDocumento2 páginasJUDICIAL NOTICE Habagat Grill v. DMC Urban DeveloperAdi LimAinda não há avaliações

- Case #11 (Batch 12)Documento2 páginasCase #11 (Batch 12)Reinald Kurt VillarazaAinda não há avaliações

- Belen Vs People, G.R. No. 211120, January 8, 2020 FactsDocumento2 páginasBelen Vs People, G.R. No. 211120, January 8, 2020 FactsKirstie Lou Sales100% (1)

- US V EvangelistaDocumento2 páginasUS V Evangelistaalexis_beaAinda não há avaliações

- Case Digest - People V QuidatoDocumento2 páginasCase Digest - People V QuidatoCherry Chao100% (1)

- Crim Information For Violation of Sec 11 9165Documento2 páginasCrim Information For Violation of Sec 11 9165Fay FernandoAinda não há avaliações

- People v. Abriol / GR No. 123137 / October 17, 2001Documento2 páginasPeople v. Abriol / GR No. 123137 / October 17, 2001Mini U. Soriano100% (1)

- Salcedo-Ortanez v. CADocumento1 páginaSalcedo-Ortanez v. CAWendy PeñafielAinda não há avaliações

- People Vs LaguaDocumento2 páginasPeople Vs LaguaRose Vivialyn LumasacAinda não há avaliações

- Regional Trial Court: Crim Cases No. 657Documento3 páginasRegional Trial Court: Crim Cases No. 657Levy DaceraAinda não há avaliações

- United States vs. Teresa Concepcion GR No. 10396 July 29, 1915Documento1 páginaUnited States vs. Teresa Concepcion GR No. 10396 July 29, 1915laika corralAinda não há avaliações

- People V UmanitoDocumento2 páginasPeople V UmanitoAnonymous fnlSh4KHIg100% (1)

- People v. VallejoDocumento2 páginasPeople v. VallejoAiken Alagban LadinesAinda não há avaliações

- Digest PP vs. CERILLADocumento3 páginasDigest PP vs. CERILLAStef OcsalevAinda não há avaliações

- Case Digest People vs. TundagDocumento1 páginaCase Digest People vs. TundagYsabelle100% (2)

- Espineli v. People and Citing Republic v. Heirs of Felipe AlejagaDocumento2 páginasEspineli v. People and Citing Republic v. Heirs of Felipe AlejagaTootsie GuzmaAinda não há avaliações

- 19 Patula vs. PeopleDocumento2 páginas19 Patula vs. PeopleNivAinda não há avaliações

- PEOPLE OF THE PHILIPPINES V CLARO Detailed DigestDocumento3 páginasPEOPLE OF THE PHILIPPINES V CLARO Detailed DigestJane Galicia100% (1)

- Datukan Malang Salibo Vs Warden (Quash Warrant of Arrest)Documento2 páginasDatukan Malang Salibo Vs Warden (Quash Warrant of Arrest)Don Astorga DehaycoAinda não há avaliações

- Auxillo, JR Vs NLRC DigestDocumento1 páginaAuxillo, JR Vs NLRC DigestSyElfredGAinda não há avaliações

- Case Digest - 20Documento2 páginasCase Digest - 20Mythel SolisAinda não há avaliações

- Tol-Noquera V Villamor DigestDocumento2 páginasTol-Noquera V Villamor DigestNinaAinda não há avaliações

- Opinion Rule People Vs Abriol Po2 Albert Abriol, Macario Astellero, and Januario Dosdos GR 123137, October 17, 2001Documento10 páginasOpinion Rule People Vs Abriol Po2 Albert Abriol, Macario Astellero, and Januario Dosdos GR 123137, October 17, 2001Dan LocsinAinda não há avaliações

- People vs. ClaraDocumento1 páginaPeople vs. ClaraGem Martle Pacson100% (1)

- PP v. Constancio - Case DigestDocumento2 páginasPP v. Constancio - Case Digestshezeharadeyahoocom100% (2)

- People vs. Espinosa DigestDocumento2 páginasPeople vs. Espinosa DigestEmir Mendoza100% (1)

- Calamba Steel v. CIR Case DigestDocumento1 páginaCalamba Steel v. CIR Case DigestKian FajardoAinda não há avaliações

- People Vs CarpoDocumento2 páginasPeople Vs CarpoGabriel Antonio ZuluetaAinda não há avaliações

- Star Two Vs Ko DigestDocumento1 páginaStar Two Vs Ko DigestLara Cacal0% (1)

- Tanzo vs. Hon. DrilonDocumento1 páginaTanzo vs. Hon. DrilonKaren GinaAinda não há avaliações

- Dela Rama Vs PapaDocumento2 páginasDela Rama Vs PapaEloisa SalitreroAinda não há avaliações

- PDF Evidence Case Digest 2Documento225 páginasPDF Evidence Case Digest 2janna cavalesAinda não há avaliações

- People of The Philippines Vs Condemena (1968)Documento2 páginasPeople of The Philippines Vs Condemena (1968)Abdulateef SahibuddinAinda não há avaliações

- 2014march - Castillo v. Prudentialife, Inc. - ConductoDocumento2 páginas2014march - Castillo v. Prudentialife, Inc. - ConductoRamon T. Conducto II100% (1)

- Sec. 25, Rule 130 Report - FinalDocumento17 páginasSec. 25, Rule 130 Report - FinalErmeline Tampus100% (1)

- People V CusiDocumento1 páginaPeople V Cusicmv mendoza0% (1)

- Leonilo Sanchez Alias Nilo, Appellant, vs. People of The Philippines and Court of AppealsDocumento6 páginasLeonilo Sanchez Alias Nilo, Appellant, vs. People of The Philippines and Court of AppealsRap BaguioAinda não há avaliações

- AFP Retirement V RepublicDocumento4 páginasAFP Retirement V RepublicPablo Jan Marc FilioAinda não há avaliações

- EDSA Shangrila Vs BF DigestedDocumento2 páginasEDSA Shangrila Vs BF DigestedKimberly RamosAinda não há avaliações

- Macasiray v. People PDFDocumento2 páginasMacasiray v. People PDFMarkNasolMadelaAinda não há avaliações

- Macasiray - v. - PeopleDocumento7 páginasMacasiray - v. - PeopleChristine Gel MadrilejoAinda não há avaliações

- Articles of IncorporationDocumento3 páginasArticles of IncorporationKaye GeesAinda não há avaliações

- State Prosecutors Vs Judge MuroDocumento2 páginasState Prosecutors Vs Judge MuroKaye GeesAinda não há avaliações

- People v. MatitoDocumento2 páginasPeople v. MatitoKaye GeesAinda não há avaliações

- Case Digest 3Documento2 páginasCase Digest 3Monique LhuillierAinda não há avaliações

- Duty of Care and The Civil Liability Act 2002 PDFDocumento26 páginasDuty of Care and The Civil Liability Act 2002 PDFTay MonAinda não há avaliações

- Updated Icrc Commentary Third Geneva Convention Prisoners War Twenty First Century 913Documento28 páginasUpdated Icrc Commentary Third Geneva Convention Prisoners War Twenty First Century 913tufa tufaAinda não há avaliações

- Oracle v. Department of Labor ComplaintDocumento48 páginasOracle v. Department of Labor ComplaintWashington Free BeaconAinda não há avaliações

- Contracts 2 Mind MapDocumento1 páginaContracts 2 Mind MapjadeftjdbAinda não há avaliações

- Admin Law Syllabus PDF SelectaDocumento11 páginasAdmin Law Syllabus PDF SelectaMichael C� Argabioso100% (1)

- Office of The Ombudsman Vs Carmencita CoronelDocumento3 páginasOffice of The Ombudsman Vs Carmencita CoronelEzekiel Japhet Cedillo EsguerraAinda não há avaliações

- Differential EquationDocumento9 páginasDifferential EquationPvr SarveshAinda não há avaliações

- Esmalin vs. NLRC DIGESTDocumento2 páginasEsmalin vs. NLRC DIGESTStephanie Reyes GoAinda não há avaliações

- G. Election Offenses Prosecution of Election Offenses: Section 1Documento15 páginasG. Election Offenses Prosecution of Election Offenses: Section 1Threes SeeAinda não há avaliações

- Pan 49 ADocumento4 páginasPan 49 ARajasekhar KollaAinda não há avaliações

- Lucy Cavendish College - Staff and FellowsDocumento4 páginasLucy Cavendish College - Staff and FellowsDavid CotterAinda não há avaliações

- Lawafrica (A) : Strathmore UniversityDocumento12 páginasLawafrica (A) : Strathmore UniversityshalzmesayAinda não há avaliações

- International Human Rights Law and Human Rights Laws in The PhilippinesDocumento28 páginasInternational Human Rights Law and Human Rights Laws in The PhilippinesFrancis OcadoAinda não há avaliações

- AFFIDAVIT To The State Dept.Documento1 páginaAFFIDAVIT To The State Dept.toski_tech5051100% (1)

- Instant Download Solution Manual For Cost Benefit Analysis Concepts and Practice 5th Edition PDF ScribdDocumento25 páginasInstant Download Solution Manual For Cost Benefit Analysis Concepts and Practice 5th Edition PDF ScribdBarbara Phillips100% (13)

- Revenue Regulations No. 2-40Documento3 páginasRevenue Regulations No. 2-40June Lester100% (1)

- Alefa Description and Goals 010515Documento2 páginasAlefa Description and Goals 010515api-241572394Ainda não há avaliações

- AGP Power FunctionDocumento20 páginasAGP Power FunctionFayaz KhanAinda não há avaliações

- Egyptian Dies, 15 Injured As Fire Breaks Out in 4-Storey BuildingDocumento1 páginaEgyptian Dies, 15 Injured As Fire Breaks Out in 4-Storey BuildingNasreen FalaahAinda não há avaliações

- Guideline MSAP 3Documento7 páginasGuideline MSAP 3AwerAinda não há avaliações

- Chemistry Topic Guide Energetics Energy and EntropyDocumento21 páginasChemistry Topic Guide Energetics Energy and EntropyGazar100% (1)

- BN 194 of 2017 Fit and Proper June 2020 2Documento48 páginasBN 194 of 2017 Fit and Proper June 2020 2Sin Ka YingAinda não há avaliações

- Philippine Airlines, Inc. vs. Jaime M. Ramos, Nilda RamosDocumento10 páginasPhilippine Airlines, Inc. vs. Jaime M. Ramos, Nilda RamosAngelReaAinda não há avaliações

- BS7889PVCDocumento2 páginasBS7889PVCdropsy24Ainda não há avaliações

- Pastel Blue Pastel Green Pastel Purple Playful Scrapbook About Me For School Presentation Party 1 PDFDocumento18 páginasPastel Blue Pastel Green Pastel Purple Playful Scrapbook About Me For School Presentation Party 1 PDFdarrelhatesyouAinda não há avaliações

- Barco v. CA, G.R. 120587, 20 January 2004Documento3 páginasBarco v. CA, G.R. 120587, 20 January 2004Deyo Dexter GuillermoAinda não há avaliações

- Taupo Hunt Week 2014 - Registration FormDocumento2 páginasTaupo Hunt Week 2014 - Registration FormSallyStrangAinda não há avaliações

- CfbrickellapplicationDocumento84 páginasCfbrickellapplicationNone None None0% (1)

- Application Form For Volunteers - Doc 1Documento5 páginasApplication Form For Volunteers - Doc 1ngan_ta2001Ainda não há avaliações