Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

Nutrition & Dietetics: Supplement

Enviado por

firdakusumaputriTítulo original

Direitos autorais

Formatos disponíveis

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Nutrition & Dietetics: Supplement

Enviado por

firdakusumaputriDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Nutrition & Dietetics

Journal of the Dietitians Association of Australia, including the Journal of the New Zealand Dietetic Association

Supplement

Evidence Based Practice Guidelines for the Nutritional Management of Malnutrition in Adult Patients Across the Continuum of Care

Editor Linda Tapsell, PhD, MHPEd, Dip Nutr Diet, BSc, MAIFST, FDAA Wollongong, New South Wales Acting Supplement Editor Ingrid Hickman, PhD, BHSc, APD Brisbane, Queensland Editorial Assistant Kristy Parsons Canberra, Australian Capital Territory Prepared by the DAA Malnutrition Guideline Steering Committee Cheryl Watterson, Grad Dip Nutr Diet, BSc, APD Director, Nutrition and Dietetics John Hunter Hospital Newcastle, New South Wales Allison Fraser, BHSc, APD Research and Development Dietitian John Hunter Hospital Newcastle, New South Wales Merrilyn Banks, PhD, MHltSc, Grad Dip Nutr Diet, Grad Dip Ed, BSc, APD Director, Nutrition and Dietetics Royal Brisbane and Womens Hospital Brisbane, Queensland Elisabeth Isenring, PhD, BHSc, AdvAPD NHMRC Australian Clinical Training Fellow Queensland University of Technology Brisbane, Queensland Michelle Miller, PhD, MNutDiet, BSc, APD Senior Lecturer Flinders University Adelaide, South Australia Caitlin Silvester, PGrad Dip Diet, Grad Dip HlthSc, BSc, APD Dietitian Beechworth Health Services Beechworth, Victoria Roy Hoevenaars, PhD, BSc(Hons), Grad Dip Nutr Diet, BSc, APD Manager, Nutrition and Dietetics Barwon Health Geelong, Victoria Judy Bauer, PhD, MHSc, GDipNutrDiet, BSc, AdvAPD Director, Nutrition and Dietetics The Wesley Hospital Brisbane, Queensland Angela Vivanti, DHSc, MAppl Sc, Grad Dip Nutr Diet, BSc, AdvAPD Research & Development Dietitian Princess Alexandra Hospital Brisbane, Queensland Maree Ferguson, PhD, MBA, Grad Dip Nutr Diet, BAppSc, AdvAPD Director, Nutrition and Dietitics Princess Alexandra Hospital Brisbane, Queensland Journal and Scientic Publications Management Committee Margaret Allman-Farinelli (Director Responsible) Anthea Magarey (Chairperson) Linda Tapsell Judy Bauer Marina Reeves Giordana Cross Clare Collins Maree Ferguson Andrea Braakhuis Jane Elmslie Claire Hewat Kristy Parsons Aims and Scope: Nutrition & Dietetics is Australia and New Zealands leading peer-reviewed Journal in its eld. Covering all aspects of food, nutrition and dietetics, the Journal provides a basic forum for the reporting, discussion and development of scientically credible knowledge related to human nutrition and dietetics. Widely respected in Australia and around the world, Nutrition & Dietetics publishes original research, review papers, viewpoint articles, insights short papers on ndings from demonstrating practice, letters, book reviews, conference reports and continuing education quizzes. Abstracting and Indexing Services: The Journal is indexed by Abstracts on Hygiene and Communicable Diseases; Agricola C R I S; Animal Bredding Abstracts; Aquatic Sciences & Fisheries Abstracts; Australasian Medical Index; Australian Family and Society Abstracts; Cumulative Index to Nursing & Allied Health Literature; Dairy Science Abstracts; EBSCO Contentville; Food Science and Technology Abstracts; Horticultural Science Abstracts; Infotrac; Infotrieve; Leisure, Recreation and Tourism Abstracts; Nutrition Abstracts and Reviews; Postharvest News and Information; Potato Abstracts; Poultry Abstracts; Review of Aromative and Medicinal Plants; Rural Development Abstracts; SAGE; Soybean Abstracts; Sugar Industry Abstracts; Tropical Diseases Bulletin; World Agricultural Economics and Rural Sociology Abstracts; World Banking Abstracts; World Magazine Bank. Address for Editorial Correspondence: Editor, Nutrition & Dietetics 1/8 Phipps Close Deakin ACT 2600 Australia Email: journal@daa.asn.au Disclaimer: The Publisher, the Dietitians Association of Australia, the New Zealand Dietetic Association, and Editors cannot be held responsible for errors or any consequences arising from the use of information contained in this journal; the views and opinions expressed do not necessarily reect those of the Publisher, the Dietitians Association of Australia, the New Zealand Dietetic Association and Editors, neither does the publication of advertisements constitute any endorsement by the Publisher, the Dietitians Association of Australia, the New Zealand Dietetic Association and Editors of the products advertised. Journal compilation 2009 (Dietitians Association of Australia). For submission instructions, subscription and all other information visit www.blackwellpublishing.com/nd This journal is available online at Wiley Interscience. Visit www. interscience.wiley.com to search the articles and register for table of contents and email alerts. Access to this journal is available free online within institutions in the devoloping world through the AGORA initiative with the FAO and the HINARI initiative with the WHO. For information, visit www.aginternetwork.org, www.healthinternetwork.org. ISSN 1446-6368 (Print) ISSN 1747-0080 (Online)

NDI.JEB.Dec09

Nutrition & Dietetics

Journal of the Dietitians Association of Australia, including the Journal of the New Zealand Dietetic Association

Volume 66 Supplement 3 December 2009 Evidence based practice guidelines for the nutritional management of malnutrition in adult patients across the continuum of care Executive summary Summary of evidence-based recommendations Introduction Evidence based statements Acknowledgement References Appendices

ISSN 1446-6368

S1 S2S3 S4S10 S11S20 S21 S22S27 S28S34

The Dietitians Association of Australia (DAA) supported the printing of these DAA-endorsed Best Practice Guidelines for the Nutritional Management of Malnutrition in Adult Patients Across the Continuum of Care.

Nutrition & Dietetics 2009; 66 (Suppl. 3): S1

Evidence based practice guidelines for the nutritional management of malnutrition in adult patients across the continuum of care

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

Malnutrition is a major international and Australian health problem, which continues to be unrecognised and therefore, untreated. It is both a cause and a consequence of ill health across many patient groups and healthcare settings. Malnutrition interferes with patients ability to benet from health treatments and affects every domain of their well-being. Additionally, it increases societys healthcare costs. This paper, Evidence based practice guidelines for nutritional management of malnutrition in adult patients across the continuum of care, has been developed to gather the best available evidence for detecting malnutrition and managing it with nutritional interventions. The Guideline Steering Committee hopes to inuence health care providers and especially dietitians to increase capacity within Australia to implement affordable detection systems, such as routine malnutrition screening. It is expected that the guidelines will provide a framework for evidence-based nutritional assessments and increase access to appropriate patient-focussed treatments for affected adults that are timely and occur both within and across hospital and primary care sectors. These guidelines are based on an agreed and rigorous process undertaken by the Steering Committee, and in accordance with the Dietitians Association of Australia (DAA) performance standards. They have resulted from the voluntary contribution of a collaboration of dietitians with clinical and research expertise across a range of practice settings. The process involved a systematic search of the literature, an assessment of the strength of the evidence, consultation with key stakeholders and the development of evidencebased statements and practice tips that may help to guide clinical practice and improve patient experience and health outcomes in Australian healthcare sectors for malnourished adults. The dissemination and implementation of the recommendations of the guidelines will be supported by the DAA.

2009 The Author. Journal compilation 2009 Dietitians Association of Australia

S1

Nutrition & Dietetics 2009; 66 (Suppl. 3): S2S3

SUMMARY OF EVIDENCE-BASED RECOMMENDATIONS

The guideline recommendations have been graded using the National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) classications for grades of recommendation1, which are as follows: Level A Body of evidence can be trusted to guide practice. Level B Body of evidence can be trusted to guide practice in most situations. Level C Body of evidence provides some support for recommendation(s) but care should be taken in its application. Level D Body of evidence is weak and recommendation(s) must be applied with caution.

1. Nutrition screening

Clinical question

1a. What is the prevalence of malnutrition and is it a problem?

Evidence-based recommendations

The prevalence of malnutrition is high worldwide (including in Australia) in all healthcare settings, yet is largely underrecognised and under-diagnosed resulting in a decline in nutritional status. Therefore, it is recommended that healthcare professionals are informed that malnutrition is associated with adverse clinical outcomes and costs. NHMRC Grade of recommendation: A Malnutrition should be identied, treated and action taken to reduce the prevalence in Australian healthcare settings and in community-dwelling adults. NHMRC Grade of recommendation: B

Clinical question

1b. Should there be routine screening for malnutrition and if so where and when should malnutrition screening occur?

Evidence-based recommendations

Routine screening for malnutrition should occur in the acute setting to improve the identication of malnutrition risk and to allow for nutritional care planning. NHMRC Grade of recommendation: B Routine screening for malnutrition should occur in the rehabilitation, residential aged care and community settings to improve the identication of malnutrition risk and enable nutritional care planning. NHMRC Grade of recommendation: D

Clinical question

1c. What screening process can be used to identify adults at risk of malnutrition?

Evidence-based recommendations

Use a valid malnutrition screening tool appropriate to the population in which it is to be applied. NHMRC Grade of recommendation: B

S2

2009 The Author. Journal compilation 2009 Dietitians Association of Australia

Practice Guidelines for the Nutritional Management of Malnutrition in Adult Patients Across the Continuum of Care

2. Nutrition assessment

Clinical question

What nutrition assessment processes can be used to diagnose malnutrition in adults?

Evidence-based recommendations

Use a valid nutrition assessment tool appropriate to the population in which it is to be applied. NHMRC Grade of recommendation: B

3. Nutrition goals, interventions and monitoring

Clinical question

3a. In adults with malnutrition or at risk of malnutrition, what are the appropriate nutrition goals, for optimal client, clinical and cost outcomes?

Evidence-based recommendations

Aim to prevent decline/improve nutritional status and associated outcomes in adults with malnutrition or at risk of malnutrition. NHMRC Grade of recommendation: A

Clinical question

3b. What are the appropriate interventions for prevention and treatment of malnutrition in adults?

Evidence-based recommendations

Nutrition interventions can improve outcomes. Consideration should be given to the healthcare setting, resources, patient/client goals, requirements and preferences. NHMRC Grade of recommendation: BC

Clinical question

3c. What are appropriate monitoring and outcome measures to demonstrate improved patient, clinical and cost outcomes?

Evidence-based recommendations

Choose standardised measures which change in a clinically meaningful way to demonstrate the outcomes of nutrition interventions. NHMRC Grade of recommendation: not applicable

2009 The Author. Journal compilation 2009 Dietitians Association of Australia

S3

Nutrition & Dietetics 2009; 66 (Suppl. 3): S4S10

1 INTRODUCTION 1.1 Purpose and scope

The purpose of these guidelines is to provide health care professionals, especially dietitians with evidence based recommendations supporting the identication and nutritional management of malnourished adults. The Evidence Based Practice Guidelines for Nutritional Management of Malnutrition in Adult Patients across the Continuum of Care focus on the identication and treatment of malnutrition in the acute, rehabilitation, residential aged care, and community settings. Although there are other international guidelines which address malnutrition,2,3 it was determined that gaps existed in these guidelines which warranted addressing and it was perceived that there would be a benet in exploring the evidence base with respect to the Australian context. Malnutrition is dened as a state of nutrition in which a deciency or excess (or imbalance) of energy, protein, and other nutrients causes measurable adverse effects on tissue/ body form (body shape, size and composition) and function and clinical outcome.4 For the purpose of these guidelines malnutrition refers solely to protein-energy under-nutrition despite the denition given above which encompasses both under- and over-nutrition. In developed countries the increasing prevalence of obesity and its resultant health consequences has contributed to the lack of recognition of under-nutrition. For nutritional treatment of obesity the reader is referred to the Best Practice Guidelines for the Treatment of Overweight and Obesity in Adults endorsed by the Dietitians Association of Australia.5 The outcomes of the implementation of these evidence based guidelines will achieve the following anticipated benets for adults with malnutrition or at risk of malnutrition: Improved access to ethical, effective and efcient patient care by developing and implementing relevant patientcentred protocols and pathways appropriate to the healthcare setting. Correct diagnosis of malnourished patients increasing recognition of the impact of this disease/ condition on patients and health service. Improved patient experience and health outcomes for identied adults. A skilled Dietitian workforce playing a key role in addressing adult malnutrition across healthcare settings by continuing advocacy of the Dietitians Association of Australia. Advocacy for appropriate and adequate food services; eating environments; staff resources and policy. Capacity building in Australian health and human services for preventing, recognising and treating malnutrition by the entire health workforce and health policy makers.

1.2 Methods

1.2.1 Guideline framework

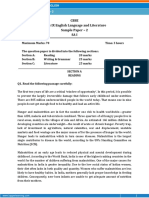

In developing these Guidelines the American Dietetic Associations Nutrition Care Process (NCP)6 has been used to dene the clinical questions for the systematic review. The NCP framework incorporates a standardised process and language as part of a conceptual model to guide and document nutrition care and patient outcomes.6 The framework includes nutrition assessment, nutrition diagnosis, nutrition intervention and nutrition monitoring and evaluation.6 This NCP framework has recently been adopted by the DAA. A trigger event initiates where and how the patient is identied for nutrition care.7 This trigger event may include nutrition screening. Since malnourished adults are often not recognised and thus fail to have access to the Nutrition Care Process, the trigger event has been added to the Guideline framework. This NCP including the trigger event is illustrated in Figure 1.7 Nutrition screening describes the process of identifying clients with characteristics commonly associated with nutrition problems who may require comprehensive nutrition assessment and may benet from nutrition intervention. These Guidelines refer to malnutrition screening which is used to identify those who may be malnourished or at risk of malnutrition. Nutrition assessment is a comprehensive approach to gathering pertinent data in order to dene nutritional status and identify nutrition-related problems. The assessment often includes patient history, medical diagnosis and treatment plan; nutrition and medication histories, nutrition related physical examination including anthropometry, nutritional biochemistry, psychological, social, and environmental aspects. Nutrition diagnosis is a clinical judgement based on data collected during the assessment phase. The set of nutrition diagnoses derived from the assessment data will give direction to prioritising treatment goals and intervention strategies. The nutrition diagnosis uses standardised terminology which identies and labels the actual occurrence, or risk of developing nutrition problems that dietitians treat independently. A nutrition diagnosis is written in PES format that states the problem (P) or nutrition diagnosis, the aetiology (E) or risk factors/ causes and the signs and symptoms (S) or measurable adverse nutrition status.8 Nutrition intervention is designed to address a nutrition problem or aetiology of the nutrition diagnosis. Nutrition interventions aim to change nutrition-related behaviour, risk factors, environmental aspects or characteristics of health status. Nutrition monitoring is the review and assessment of a patients status at a scheduled follow-up point with regard to the nutrition diagnosis, intervention plans/ goals, and outcomes. 2009 The Author Journal compilation 2009 Dietitians Association of Australia

S4

Practice Guidelines for the Nutritional Management of Malnutrition in Adult Patients Across the Continuum of Care

The Nutrition Care Process

Screening & Referral System Identify risk factors Use appropriate tools and methods Involve interdisciplinary collaboration

Practice Settings

Co d

e of

Ethics

Diet e

tics

Kn ow l ed ge

Pr ac t

Nutrition Assessment & Re-assessment

Obtain/collect timely & appropriate data Analyze/interpret with evidence-based standards Document

ice

Nutrition Diagnosis

Identify & label problem Determine cause/contributing risk factors Cluster signs & symptoms/defining characteristics Document

Evidenc e-b ase d

lth Hea

Competencies Skills &

Economics

Care System s

Relationship Between Patient/Client/Group & Dietetics Professional

Nutrition Monitoring & Evaluation

Monitor progress Measure outcome indicators Evaluate outcomes Document

Nutrition Intervention

Plan nutrition intervention Formulate goals & determine a plan of action Implement nutrition intervention Care is delivered & actions are carried out Document

Outcomes Management System Monitor the success of the Nutrition Care Process Implementation Evaluate the impact with aggregate date Identify and analyze causes of less than optimal performance and outcomes Refine the use of the Nutrition Care Process

Figure 1 American Dietetic Association Nutrition Care Process and Model7. Reproduced with the permission of Elsevier.

Outcome evaluation is the systematic comparison of current ndings with previous status, intervention goals, or reference standards. Outcomes which can be used to show the effectiveness of nutrition interventions can be grouped into direct nutrition outcomes, clinical and health status outcomes, patient-centred outcomes, and health care utilisation and cost outcomes.9

1.2.2 Literature appraisal and collation

Developing the literature search strategy and clinical questions Relevant clinical questions were developed for components of the Nutrition Care Process (Figure 1). A systematic literature review of studies was designed to address the clinical questions using appropriate search terms and methodologies. Three searches were written for the Medline Database using the OVID search engine and then modied to suit Embase and CINAHL databases. The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews was searched for all papers relating to malnutrition. The searches were limited to the English language and studies involving humans. Limits were added which excluded tutorials, editorials, news, letters and comments. Articles not reported in full (abstract only) were also excluded. Preliminary inclusion and exclusion criteria were dened by agreement of the Steering Committee and included in the search methodology where applicable. Please refer to Appendix 1 for the detailed search strategy. The clinical questions were as follows: 2009 The Author Journal compilation 2009 Dietitians Association of Australia

1. Criteria for screening and referral systems (Figure 1): What is the best method for identication of adults with malnutrition or at risk of malnutrition for improved patient, clinical and cost outcomes? 2. Nutrition assessment (and Nutrition Diagnosis) (Figure 1): Which specic measures best reect nutritional status or change in nutritional status in adults with malnutrition or at risk of malnutrition, for the diagnosis of malnutrition, can be altered by nutritional intervention, and are associated with improved patient, clinical and cost outcomes? 3. Nutrition intervention; Nutrition monitoring and evaluation (Figure 1): a) What are the nutrition goals for adults with malnutrition or at risk of malnutrition for improved patient, clinical and cost outcomes? b) In adults with malnutrition or at risk of malnutrition, what are the appropriate nutrition interventions, to optimise nutritional status for improved patient, clinical and cost outcomes? c) In adults with malnutrition or at risk of malnutrition, how will nutrition interventions be monitored for improved patient, clinical and cost outcomes? All searches were conducted to August 2006. For the rst two clinical questions databases were searched from inception of the databases whereas the nal question (Q3) was from 1996. The searches returned a total of 3987 titles and abstracts for review. In response to the large number of S5

a itic Cr

lT

g kin hin

Social Systems

Collaboratio n

Co m m u

ca ni

n t io

Nutrition & Dietetics 2009; 66 (Suppl. 3): S4S10

Table 1 Final Guideline clinical questions Nutrition Care Process Nutrition Screening Clinical questions which informed the systematic search Q1a) What is the prevalence of malnutrition and is it a problem? 1b) Should there be routine screening for malnutrition and if so where and when should malnutrition risk screening occur? 1c) What screening process can be used to identify adults at risk of malnutrition? Q2. What nutrition assessment processes can be used to identify malnutrition in adults? Q3a) In adults with malnutrition or at risk of malnutrition, what are the appropriate nutrition goals, for optimal client, clinical and cost outcomes? Q3b) What are the appropriate nutrition interventions for prevention and treatment of malnutrition in adults? Q3c) What are appropriate monitoring and outcome measures to demonstrate improved patient, clinical and cost outcomes?

Table 2 Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria Inclusion criteria Protein-energy malnutrition Undernutrition Energy deciency Protein deciency Adults Medical Nutrition Therapy Measurements of Nutrition Status (eg biochemistry, anthropometry) Screening for Protein-Energy Malnutrition Assessments of Nutrition status (e.g. Assessment tools) Nutrient intakes Exclusion criteria Non-English language Children/ Paediatrics Specic Vitamin Deciencies (e.g. Vitamin D) Specic Mineral Deciencies (e.g. Magnesium) Eating Disorders (anorexia or bulimia) Cystic Fibrosis Coeliac Disease

Nutrition Assessment and Nutrition diagnosis Nutrition goals (a)

Obesity surgery (Gastric bypass/ bands) Liver Disease

Nutrition interventions (b)

Nutrition monitoring and evaluation (c)

abstracts retrieved, the Steering Committee made some modications to manage the literature appraisal as follows: The search for the nutrition screening tool section was modied to focus on the main recommendations from the Jones review in 200610 of 44 nutrition screening and assessment tools describing literature until the year 2000 and also any identied relevant articles of screening tools with level III-2 evidence or higher to support their use published after 2000. Ninety-six articles were identied published between January 2000 and November 2008. Since August 2006 modications have been made to the clinical questions. A newly devised question has been added to determine whether malnutrition is a problem in Australia (prevalence) and question 1 has been split into parts to enhance the focus of the evidence based statements. Diagnosis was removed from the clinical questions when the International Statistical Classication of Diseases and Related Health Problems 10th Revision Australian Modication (ICD-10-AM) criteria for diagnosing malnutrition was released.11 Consequently the new ICD-10-AM diagnostic criteria for malnutrition has been included in the document as a Nutrition Assessment practice tip. Please refer to Table 1 for the nal clinical questions. For question 1a evidence was extracted from Strattons comprehensive review of studies until 2003 investigating the S6

Renal disease and Chronic Kidney Disease Dialysis and Haemodialysis Nutrition interventions(a) Nutrition monitoring Hereditary protein deciency disorders Complications, mortality Non-Systematic reviews/ and morbidity relating to opinions/viewpoints malnutrition Unspecied nutritional Non-Western Countries deciency Critical care Crohns Disease Alcoholism Alcoholism if malnutrition is vitamin related Prevalence data only Cancer Screening tools with 2 HIV parameters for the screening section only

Note: if nutrition interventions included an exercise component, these studies were included in the guidelines, however pharmaceutical interventions are not specically addressed in these Guidelines. HIV, Human Immunodeciency Virus.

(a)

prevalence and consequences of malnutrition.12 A literature search was then conducted to identify international reviews between 2003 and 2008 as well as all published papers which investigated malnutrition prevalence in an Australian or New Zealand population. The literature identied in the searches for the initial clinical questions along with the literature attained from the additional clinical question (question 1a) was then appraised for the guidelines. Seventy-eight papers (including the Stratton review) met the inclusion criteria (refer to Table 2) for question 1a and b.12 In addition to the Jones 2006 review,10 41 papers published between January 2000 and November 2008 met the inclusion criteria for the screening tool part of the question (question 1c). For question 2, twenty-ve 2009 The Author Journal compilation 2009 Dietitians Association of Australia

Practice Guidelines for the Nutritional Management of Malnutrition in Adult Patients Across the Continuum of Care

papers were assessed as meeting the inclusion criteria and included an assessment tool measured against a means of conrming validity. One hundred and four papers were assessed as meeting the inclusion criteria for question 3 and retrieved for full appraisal. Thus, a total of 249 papers were reviewed for the guidelines. A minimum of two Steering Committee members independently assessed the titles and abstracts using the inclusion and exclusion criteria (Table 2) before retrieving the full article. Criteria were added when the reviewers commenced assessing the literature and determined further criteria were needed to ensure the scope of the guidelines remained focussed. Additional criteria exclude conditions and diseases which were already the subject of other DAA evidence based guidelines or were alternate, potentially co-existing mechanisms for protein-energy malnutrition such as sarcopenia or cachexia (please refer to existing DAA endorsed evidence based practice guidelines: Evidence Based Practice Guidelines for Nutritional Management of Patients Receiving Radiation Therapy,13 Cancer Cachexia,14 Chronic Kidney Disease,15 and Australasian Clinical Practice Guideline for Nutrition in Cystic Fibrosis.16) Tables were developed to collate the evidence for screening, assessment, intervention, monitoring and evaluation. Evidence was categorised by health care setting and patient characteristics as described in Table 3.

Table 3 Denitions used for collating evidence based statements Setting/ Demographic Acute Care Denition for the purpose of collating the evidence based statements Acute Care is dened as services occurring within an acute care hospital Rehabilitation is dened as services by a multidisciplinary team with the goal of reducing disability by improving task-oriented behaviour.17 Rehabilitation settings include both inpatient and ambulatory settings. Residential Aged Care is dened as services for aged people who can no longer be assisted to stay in their home.18 Residential aged care settings involve both low (hostel) and high care (nursing home). Community is dened as free living adults with or without assistance from community services. Across settings is used to describe evidence which involved participants or analysis in two or more of the above settings. Groups of study participants had a mean age over 60 years.

Rehabilitation

Residential Aged Care

Community

Across settings

1.2.3 Rating the evidence

The strength of the evidence was assessed using the level of evidence rating system recommended by the National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) additional levels of evidence and grades of recommendations for developers of guidelines-Pilot Program (Appendix 2).1 NHMRC level of evidence of rating scheme is provided for various types of studies including: intervention; diagnosis; prognosis; aetiology; and screening (Appendix 2). Aetiology study criteria were used for clinical questions 1a and 1b Diagnostic studies were used for clinical questions 1c and 2 Intervention studies were used for clinical questions 3 a), b) &c) In all cases the evidence was ranked by two independent reviewers. Any disagreements between reviewers were handled by a third independent reviewer. This evidence then informed the evidence based statements. Only articles assessed as providing the highest level of evidence were included in the evidence based statements. However, with respect to the evidence base in the Australian and New Zealand populations, this evidence is also presented, where available, in addition to the higher level evidence from international studies. Unfortunately no New Zealand studies were located. This approach was supported by Dietitian stakeholder consultation in May 2008. Articles identied to be the same level of evidence but reporting inconclusive ndings have been noted. Articles were excluded if they reported inconclusive ndings and were reviewed as being of a lower level of evidence than articles 2009 The Author Journal compilation 2009 Dietitians Association of Australia

Older adult

Note: Literature describing the setting as sub-acute was reviewed closely and reported according to the setting for which the participants were most aligned. In most cases these were the acute and rehabilitation settings.

supporting the evidence based statement. Some articles were assigned two levels of evidence. This was to demonstrate the difference between ndings generated from analyses performed within (Level IV) and between group (Level II-III-3). If no evidence was returned during the search this was identied as no evidence located in the evidence based statements. The grades of recommendations were then formulated from the evidence based statements. The ve components that are considered in judging the body of evidence to apply a grade of recommendation according to the NHMRC classication are the volume of evidence, consistency of the results, potential clinical impact of the proposed recommendation, and the generalisability of the body of evidence to the Australian health care context (Appendix 2).1 The grades of recommendation are: Level A Body of evidence can be trusted to guide practice. Level B Body of evidence can be trusted to guide practice in most situations. Level C Body of evidence provides some support for recommendation(s) but care should be taken in its application. S7

Nutrition & Dietetics 2009; 66 (Suppl. 3): S4S10

Level D

Body of evidence is weak and recommendation(s) must be applied with caution. A process of decision making to deal with any conict arising between members of the Steering Committee was agreed upon. If one or more Steering Committee members were in disagreement with the majority then these Committee members were requested to seek additional information to support their position. If the conict was unable to be resolved at this point then the process was for the Steering Committee to seek advice from an independent expert.

1.2.4 Development of the practice tips

Whilst evidence based statements are objective interpretations of available evidence, practice tips were developed by the Committee where there was insufcient high level evidence from the literature to support an evidence based statement, but enough low level evidence and/or expert opinion to provide a statement of support for a practice approach. The practice tips contained within these Guidelines acknowledge the diversity of settings and age related target groups and are often an extension to relevant evidence based statements in order to provide further detail or clarication. In all cases, the practice tips have required consensus by all members of the Committee and external reviewers. The Committee also recommends that evidence based recommendations and practice tips contained in this document are read in conjunction with relevant complementary guidelines. Some examples include the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) Nutrition support in adults,3 European Society of Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition (ESPEN) guidelines on adult enteral nutrition19 and the stroke guidelines.20,21 The development process for these other Guidelines allowed recommendations based on both formal and informal consensus methods using expert opinion when there was an absence of scientic literature.

1.3 Consultation process

At the DAA 26th National Conference in 2008, a formative consultation with dietitians was sought on: relevant content, ease of use, clarity of recommendations, organisational barriers and whether or not these guidelines would be used in practice. The feedback provided by the ninety ve participants indicated that the majority of dietitians understood the Guideline development process; found that the Guideline format and structure were easy to follow; that the overall objectives were clear and that the evidence based recommendations were specic and unambiguous. Participants strongly agreed that they would use the Guidelines as part of their everyday practice. Most agreed that the Guidelines would help to bridge the gap between research and practice and that the Guidelines would result in the anticipated benets claimed. Specic feedback on improvements to the document were considered by the Committee and incorporated as appropriate. For example, a range of DAA endorsed evidence based S8

practice guidelines, were reviewed and cross referenced with the current document where relevant. These included; Evidence based practice guidelines for nutritional management of radiation therapy,13 cancer cachexia,14 chronic kidney disease15 and cystic brosis.16 The Committee decided that it was also important to include information on disease states such as cancer, renal disease and (Human Immunodeciency Virus/ Acquired Immune Deciency Syndrome ) HIV/ AIDS in order to answer question 1a. What is the prevalence of malnutrition and is it a problem?. However, these diseases are not referred to in later questions; instead reference is made to the above guidelines. Further, where participants identied gaps in the literature in the intervention section, additional studies were located including studies published after the nal date of the systematic search. A list of barriers to the implementation of the Guidelines in workplaces across the continuum of care were identied by workshop participants in 2008. Another workshop was held at the DAA 27th National Conference in 2009 which focussed on addressing the barriers to implementation previously identied. This body of work is discussed under Applicability. As part of the DAA guideline development process, these Guidelines have been independently reviewed by experts and assessed using the Appraisal of Guidelines for Research and Evaluation (AGREE) instrument.22 Modications to these Guidelines have been undertaken in response to this review. Since the Steering Committee acknowledge that dietitians do not act alone in either the detection or treatment of malnourished patients, it was considered important to consult with a wide range of health professionals and consumers of health services. The March 2008 version was circulated by DAA on behalf of the Steering Committee for multidisciplinary feedback to a range of organisations including: Aged Care Association Australia (ACAA) Australasian Podiatry Council Australian Association for Exercise and Sports Science Australian Association of Gerontology Australian Association for Quality in Health Care (AAQHC) Australian Association of Occupational Therapists Australian Association of Social Workers Australian General Practice Network Australian Physiotherapy Association Australian Psychology Society Australian College of Health Service Executives (ACHSE) Australian Meals On Wheels Australian New Zealand Society for Geriatric Medicine Institute of Hospitality in Healthcare Royal College of Nursing Australia Services for Australian Rural and Remote Allied Health (SARRAH) Services for Australian Rural and Remote Allied Health Society of Hospital Pharmacists of Australia Speech Pathology Australia The Royal Australasian College of Physicians 2009 The Author Journal compilation 2009 Dietitians Association of Australia

Practice Guidelines for the Nutritional Management of Malnutrition in Adult Patients Across the Continuum of Care

The Steering Committee sought comments from the above organisations regarding identication of relevant outcomes, target audiences, format for different users, obstacles to implementation, and formulation of implementation strategies. Unfortunately, despite the request for feedback from some twenty organisations, including two patient advocacy groups, feedback was received from only three organisations: Speech Pathology Australia; Royal College of Nursing Australia; and the Australian New Zealand Society for Geriatric Medicine. All feedback was discussed by the Steering Committee and incorporated into this nal version of the guidelines where appropriate. Further engagement with stakeholders will be undertaken as part of the launch by DAA of these guidelines and a formal stakeholder consultation will be incorporated into the strategic review plan.

1.4 Review process

The Guideline review process will be undertaken by the establishment of an implementation committee. The role of this committee will be to regularly review the evidence base and recommendations for practice. The implementation committee will establish an implementation and evaluation strategic plan in association with DAA. One focus will be to evaluate the contribution of the Guidelines towards achieving the anticipated benets listed at the front of the document. Another will be increasing awareness of this health issue and participation amongst stakeholders including patients in implementing sustainable practice change. This will be accomplished by converting these guidelines to a living document by using the Wiki format (refer to http://wiki.org for further information). This will allow ongoing comment by the target audience and timely revision of the document based on new evidence by the implementation committee. It is anticipated that at least bi-annual review will occur. The workshops conducted in 2008 and 2009 have also begun the evaluative phase of the guidelines and will continue as a result of the national guideline dissemination process.

1.5 Applicability

Although, these Guidelines provide the best available evidence and a framework to aid clinical decision making, they do not replace health professionals responsibility to make decisions appropriate to the circumstances of the individual patient. Malnutrition identication and treatment processes must conform with ethical and legal requirements. The best interests of the patient should be paramount; this includes a consideration of the risks and benets of identifying and treating malnutrition for the individual patient. Treatment must be undertaken with the informed consent of the patient or carer.3 Nutrition support management should be individualised and include the patients preferences and allow for commu 2009 The Author Journal compilation 2009 Dietitians Association of Australia

nication difculties or cognitive impairments. In addition, it needs to be culturally appropriate, comprehensive, and coordinated across all relevant disciplines and settings. The goals and outcomes of nutrition intervention will be dependent on the diagnosis and prognosis of the person. Patients need to be managed in the context of their co-morbidities. The benets and risks including potential adverse effects of any nutrition treatment such as risk of swallowing impairment need to be assessed and explained to the individual patient.3 For persons with end-stage disease the desired outcome of nutritional management is to maximise patient comfort and quality of life. The publication, Guidelines for a Palliative Approach in Residential Aged Care23 may help inform health professional decision making around physical symptom assessment and management for patients with end-stage disease. Putting evidence into practice is difcult.24 For these Guidelines to have an effect on reducing the burden of malnutrition on the Australian population there needs to an effective dissemination and implementation strategy. Innovations require one or more health professionals to lead, support and drive them through. Dietitians are ideally placed to act as clinical lead in applying this Guideline across Australian healthcare settings. Clinical coordinators are recognised as amongst the most effective implementation strategies.25 Practice change strategies coordinated by dietitian co investigators have been shown to lead to successful implementation of an evidence based guideline in a complex Australian healthcare setting.26 Also the DAA Board is committed to an active role in disseminating the Guideline by publication and to holding continuing professional development activities (road shows) around Australia to which all stakeholders will be invited. The DAA website, www.daa.asn.au will provide a link to the Guideline in both the members section (DINER) and a webpage available to non-members. National dissemination will support Dietitians to develop skills in organising screening pathways and using valid assessment tools. The DAA website will also link members with relevant implementation resources.27,28 The new National Competency Standards for Entry Level Dietitians in Australia29 now include performance criteria which support knowledge and skills in nutrition screening and assessment tools. National workshops conducted in 2008 and 2009 have resulted in participants identifying barriers and discussing solutions to overcoming these barriers (enablers) using the National Institute of Clinical Studies (NICS) barrier tool.30 Barriers typically included time, skills, knowledge and organisational agenda. Recognition of the importance of addressing malnutrition in a health setting together with staff/colleague willingness to prioritise management of malnutrition is a necessity for successful implementation.

1.6 Editorial Independence

The Guidelines were developed without the assistance of commercial sponsorship. As highlighted in the S9

Nutrition & Dietetics 2009; 66 (Suppl. 3): S4S10

Acknowledgements section of these guidelines, some funding was provided by both Hunter New England Population Health (Steering Committee Research Ofcer to devise and conduct a systematic review of the literature) and DAA (funded one face to face Steering Committee Meeting). In

kind support was provided by the employers of the Steering Group. To ensure integrity of the recommendations in these guidelines, Steering Committee members who were also authors of an article being reviewed were removed from the process of evaluating the article for levels of evidence.

S10

2009 The Author Journal compilation 2009 Dietitians Association of Australia

Nutrition & Dietetics 2009; 66 (Suppl. 3): S11S20

EVIDENCE BASED STATEMENTS 1. Nutrition Screening

Clinical question

1a: What is the prevalence of malnutrition and is it a problem?

Evidence Statement There is a high prevalence of malnutrition in the: Acute care setting (in the order of 2050%) Level of Evidence (using Aetiology criteriaAppendix 1) Level l12,31 Level ll3234 [Aus] Level IV3537 [Aus] Level l12 Level II32,3840 [Aus] Level l12 Level IV35,41 Level l12 Level IV42,43 [Aus]

Rehabilitation setting (in the order of 3050%) Residential aged care setting (in the order of 4070%) Community setting (in the order of 1030%)

The prevalence of malnutrition is higher in certain groups of individuals eg. in older adults; and in certain disease states: Older adults Level l12 Level IV35 [Aus] Cancer Level l12 Level IV35 [Aus] Critical illness Level l12 Level IV35 [Aus] Neurological disease Level l12 Orthopaedic injury Level l12 Level IV44 [Aus] Respiratory disease Level l12 Level IV45 [Aus] Gastrointestinal and liver disease Level l12 Renal disease Level l12 HIV and AIDS Level l12 Malnutrition is associated with adverse clinical outcomes and costs in the: Acute care setting Rehabilitation setting Residential aged care setting Community setting Malnutrition is under-recognised and under-diagnosed in the: Acute care setting Rehabilitation setting Residential aged care setting Community setting Level l12 Level II3840 [Aus] 46,47 Level II48 Level l12 Level II43 [Aus] Level I12,49 Level IV36,37 [Aus] Level l12 Level II39 [Aus] Level l12,49 Level lV50 [Aus] Level I12,49

Identication, documentation and coding of malnutrition results in a favourable reimbursement under casemix funding in the: Acute care setting Level II33 [Aus], 5153 Other settings Not applicable

2009 The Author Journal compilation 2009 Dietitians Association of Australia

S11

Nutrition & Dietetics 2009; 66 (Suppl. 3): S11S20

Nutritional status deteriorates in a signicant proportion of individuals over the course of admission in the: Acute care setting Level II5458 Rehabilitation setting Level II59 [Aus] Residential aged care setting No evidence located Community setting No evidence located Recommendations The prevalence of malnutrition is high worldwide (including in Australia) in all healthcare settings, yet is largely under-recognised and under-diagnosed resulting in a decline in nutritional status. Therefore, it is recommended that healthcare professionals are informed that malnutrition is associated with adverse clinical outcomes and costs. NHMRC Grade of recommendation: A Malnutrition should be identied, treated, and action taken to reduce the prevalence in Australian healthcare settings, and in community dwelling adults. NHMRC Grade of recommendation: B Clinical question

1b: Should there be routine screening for malnutrition and if so where and when should malnutrition screening occur?

Evidence Statement Level of Evidence (using Aetiology criteriaAppendix 1)

Implementation of malnutrition risk screening programs improves the identication of individuals at risk of malnutrition. Acute care setting Level II52,60 Rehabilitation setting No evidence located Residential aged care setting No evidence located Community setting Level lV61 Implementation of routine malnutrition risk screening facilitates timely and appropriate referral for nutrition care in settings. Acute setting Level II60,62,63 Rehabilitation setting No evidence located Residential aged care setting No evidence located Community setting Level lV61 There is no available evidence to determine the required frequency of routine malnutrition screening across settings. Across all settings No evidence located Recommendations Routine screening for malnutrition should occur in the acute setting to improve the identication of malnutrition risk and to allow for nutritional care planning. NHMRC Grade of recommendation: B Routine screening for malnutrition should occur in the rehabilitation, residential aged care and community setting to improve the identication of malnutrition risk and enable nutritional care planning. NHMRC Grade of recommendation: D Clinical question

1c: What screening process can be used to identify adults at risk of malnutrition?

Evidence Based Statement In the acute care setting, valid malnutrition screening tools include: Malnutrition Screening Tool (MST)64 [Aus] Malnutrition Universal Screening Tool (MUST)66 Mini Nutritional Assessment-Short Form (MNA-SF)71 older adults only Nutritional Risk Screening (NRS-2002)73 Simplied Nutritional Assessment Questionnaire (SNAQ(c))62 Level of Evidence (using Diagnostic criteriaAppendix 1) Level Level Level Level Level Level II65 III-264 [Aus] III-26670 III-172 III-268,69,73 II65

S12

2009 The Author Journal compilation 2009 Dietitians Association of Australia

Practice Guidelines for the Nutritional Management of Malnutrition in Adult Patients Across the Continuum of Care

In the rehabilitation setting, valid malnutrition screening tools include: MNA-SF71 Rapid Screen40 [Aus] In the residential aged care setting, valid malnutrition screening tools include: MNA-SF71 older adults only MUST66 Simplied Nutritional Appetite Questionnairec (SNAQ)78 Simple Nutrition Screening Tool79,80 In the community setting, valid malnutrition screening tools include: MNA-SF71 older adults only MUST66 Seniors in the Community: Risk Evaluation for Eating and Nutrition (SCREEN II)81 older adults only SNAQ78 (a) SNAQ(c)62

Level III-274 [Aus], 71 Level II40 [Aus] Level Level Level Level III-271,75,76 III-277 III-278 III-279,80

Level III-271,75 Level III-266 Level III-181 Level III-278 Level II82

Recommendation Use a valid malnutrition screening tool appropriate to the population in which it is to be applied. NHMRC Grade of recommendation: B

a

NB: there are two different screening tools called SNAQ; one developed in the USA78 and one developed in the Netherlands.62

Malnutrition Screening Practice Tips:

1a.i. Determination of malnutrition prevalence conduct a single day survey of the nutritional status of a majority of patients, residents or clients in your setting using a validated nutrition assessment tool (refer to Question 2). Prevalence of malnutrition = number of malnourished patients/total number of patients assessed. 1a.ii. In the acute setting, consider determination of potential reimbursement of coding for malnutrition under casemix funding.33 Refer to Nutrition Assessment practice tip 2.iii. 1a.iii. Reasons to exclude certain patient groups from malnutrition screening include: groups with low risk of malnutrition e.g. obstetric patients, who are unlikely to benet from intervention; or very high risk of malnutrition e.g. head and neck cancer patients requiring mandatory referral for nutritional intervention.13,49 1b.i. Malnutrition screening could be performed by people who come into contact with all individuals at risk of malnutrition such as nursing staff, assistants, administrative staff, doctors or directly by patients/ carers themselves. Who performs malnutrition screening may be dependent on the setting or specic facility e.g. dietetic assistants may conduct screening in rural facilities, whereas nursing staff may do this in tertiary hospitals.64 1b.ii. The malnutrition screen should be incorporated into standard processes e.g. admission forms, patient information sheets or residential aged care forms.49 1b.iii. Repeat malnutrition screening for those initially screened as at low risk. Due to lack of studies, there are no evidence-based statements regarding the frequency of nutrition screening, but examples of recommended screening frequency include: ideally rescreening weekly in hospital or rehabilitation 3 monthly in residential aged care settings,83 and annually in the community setting (perhaps by GP, practice nurse, MOW, HACC), or more frequently where there is clinical concern.42,84 1c.i. Select a valid malnutrition screening tool for your setting. Most of the valid malnutrition screening tools contain similar parameters. Some tools are very similar e.g. Rapid Screen40 and Simple Nutrition Screening tool79,80 both consist of Body Mass Index (BMI) and percentage weight loss. Key considerations for choice of a screening tool include: who will be undertaking the screening e.g. skill level, time to undertake; and burden of completion e.g. number of questions, measurements, equipment and calculations that may be required (refer to Appendix 3). For example; to determine BMI requires equipment for measurements, a certain level of skill to undertake the measurements and calculation of the actual BMI, which may result in the tool not being completed correctly.85 For calculation of BMI in older adults, an appropriate alternative method for estimating standing height is to measure knee height according to standard protocol and using purpose specic equipment.86 1c.ii. A scored malnutrition screening tool can help with workload management issues by prioritising those patients with the greatest need for nutrition support.64 1c.iii. Single parameters, such as Corrected Arm Muscle Area (CAMA), BMI and albumin, have some evidence of predictive validity8790 however, screening tools with at least two parameters are recommended because there is evidence that they have higher sensitivity and specicity at predicting nutritional status. 2009 The Author Journal compilation 2009 Dietitians Association of Australia S13

Nutrition & Dietetics 2009; 66 (Suppl. 3): S11S20

1c.iv. For patients identied as at risk of malnutrition, a process for assessment, intervention and monitoring needs to be put in place appropriate to the setting. It is important to regularly audit compliance with nutrition screening processes and address identied barriers. 1c.v. If the client has been referred to a dietitian by direct methods e.g. medical referral, nutrition screening is unnecessaryproceed directly to nutrition assessment and intervention. For details of screening tools validated in cancer and chronic kidney disease refer to the DAA endorsed guidelines by Isenring et al. 2008,13 Bauer et al. 200614 and Australia and New Zealand Renal Guidelines Taskforce.15

2. Nutrition Assessment

Clinical question

What nutrition assessment processes can be used to diagnose malnutrition in adults?

Evidence Based Statement In the acute care setting valid nutrition assessment tools include: Subjective global assessment (SGA)91 all adults Mini-nutritional assessment (MNA)97 (a) undertaken in older adults only Patient generated subjective global assessment (PG-SGA)102 all adults In the rehabilitation setting valid nutrition assessment tools include: Subjective global assessment (SGA) undertaken in older adults only Mini-nutritional assessment (MNA) undertaken in older adults only In the residential aged care setting valid nutrition assessment tools include: Subjective global assessment (SGA) undertaken in older adults only Mini-nutritional assessment (MNA) undertaken in older adults only In the community setting valid nutrition assessment tools include: Subjective global assessment (SGA) undertaken in older adults only Mini-nutritional assessment (MNA) undertaken in older adults only Level of Evidence (using Diagnostic criteriaAppendix 1) Level III-192,93 Level III-29496 Level III-275,95,98101 Level III-2103 (b) [Aus]

Level II104 Level III-239,47,105

(b)

Level III-248

(b)

Level III-275,98,105,106

Level III-2107 Level III-243 [Aus], 108 (b), 107,75,101 (b)

Recommendation Use a valid nutrition assessment tool appropriate to the population in which it is to be applied. NHMRC Grade of recommendation: B

Any modied versions of the MNA, SGA and PG-SGA (including cutoffs) cannot be assumed as validated until evaluated across a range of settings, against recognised nutrition assessment parameters, with adequate power. (b) Level of Evidence assessed using predictive (but not clinical) validity.

(a)

Nutrition Assessment Practice Tips:

2. Select a valid nutrition assessment tool for diagnosing protein-energy malnutrition which meets the needs of your setting, ideally across all patient/ client groups. 2.i. Training is required for the correct application of nutrition assessment tools. 2.ii. Nutrition assessment may not always be able to be completed immediately and more information may need to be sought, for example; from families of patients with communication or cognition difculties, or from interpreters for non-English speaking patients, or by direct observation of food intake, before a diagnosis of malnutrition can be made. However this should not preclude commencing a nutrition intervention. S14 2009 The Author Journal compilation 2009 Dietitians Association of Australia

Practice Guidelines for the Nutritional Management of Malnutrition in Adult Patients Across the Continuum of Care

2.iii. To diagnose malnutrition, use the ICD-10-AM Sixth Edition11 criteria (see Appendix 3): E43 Unspecied severe protein energy malnutrition In adults, BMI < 18.5 kg/m2 or unintentional loss of weight ( 10%) with evidence of suboptimal intake resulting in severe loss of subcutaneous fat and/or severe muscle wasting. E44 Protein-energy malnutrition of moderate and mild degree In adults, BMI < 18.5 kg/m2 or unintentional loss of weight (59%) with evidence of suboptimal intake resulting in moderate loss of subcutaneous fat and /or moderate muscle wasting. In adults, BMI < 18.5 kg/m2 or unintentional loss of weight (59%) with evidence of suboptimal intake resulting in mild loss of subcutaneous fat and/or mild muscle wasting. Amendments were made to the criteria for diagnosis of malnutrition in ICD-10-AM Sixth Edition (July 2008). In the acute care setting, clinical coders will now assign the appropriate code for malnutrition if there is adequate documentation by a dietitian. Consequently, dietitians need to ensure that nutrition documentation meets the diagnostic criteria. It is important to liaise with clinical coders in the acute care setting to discuss how the organisations documentation meets the diagnostic criteria. A malnutrition sticker may be useful to help identify patients to coders and standardise dietetic practice. In several Australian states in acute care facilities, assignment of the correct malnutrition code in some cases may increase the complexity and comorbidity level and thus, alter the Diagnosis Related Group and increase the casemix funding to the facility. 2.iv. The inclusion of BMI < 18.5 kg/m2 is based on World Health Organisation (WHO) criteria. However, in all settings clients with a higher BMI may be malnourished. There is evidence to suggest that weight loss of 5% annually is predictive of poor outcomes in older adults in acute and community settings.88,109,110 The mini nutritional assessment (MNA) acknowledges a higher BMI cut off for older adults.97 Unintentional weight loss is a better predictor of malnutrition than a weight or BMI at a single time point. For weight loss, a timeframe of 3 to 6 months is the consensus opinion,3 however clinical professional judgement should be used. 2.v. Single parameters have some evidence of predictive validity for nutrition assessment, however the same limitations apply here as for malnutrition screening (see practice point 1c.iii.). Valid assessment tools are recommended because they have higher sensitivity and specicity at predicting nutritional status. 2.vi. Subjective Global Assessment (SGA) and PG-SGA have previously been identied as valid methods of assessing nutritional status in patients as determined by levels of evidence in DAA Evidence Based Practice Guidelines for Nutrition Management Cancer Cachexia (SGA and PGSGA), Patients Receiving Radiation Therapy (SGA and PGSGA) and Chronic Kidney Disease (SGA).1315 2.vii. During nutritional assessment, as well as collecting pertinent data for diagnosing malnutrition, make sure to collect data on the aetiology or contributing causes of the low BMI, unintentional weight loss, and/or poor intake. These may include physiological causes such as altered nutrient need, malabsorption, Dysphagia, socio-economic causes such as lack of access to food, poor nutrition related knowledge, and psychological causes such as depression, dementia, and/or eating disorder. These causes of malnutrition are identied to inform the nutrition care process.8,9

3. Nutrition Goals, Interventions and Monitoring

Clinical question

3a: In adults with malnutrition or at risk of malnutrition, what are the appropriate nutrition goals, for optimal client, clinical and cost outcomes?

Evidence Statement Level of Evidence (using Intervention criteriaAppendix level 1)

In all settings improved outcomes may be achieved by establishing nutrition goals which focus on: Prevention of decline in nutritional status and associated adverse Level I3,111114 outcomes such as increased complications, including infections; incidence of pressure ulcer formation and mortality. Optimising nutritional status and other health outcomes by Level I3,112,115,116 improving total nutrient intake and body anthropometry in collaboration with the multidisciplinary team by timely interventions which are appropriate to the patients needs. Recommendation Aim to prevent decline/ improve nutritional status and associated outcomes in adults with malnutrition or at risk of malnutrition. NHMRC Grade of recommendation: A 2009 The Author Journal compilation 2009 Dietitians Association of Australia S15

Nutrition & Dietetics 2009; 66 (Suppl. 3): S11S20

Clinical question

3b: What are the appropriate interventions for prevention and treatment of malnutrition in adults?

Setting

(b)

Outcome(a)

Level of evidence

Modications to food provision methods may improve outcomes including: Level II Acute care Energy intake and weight status117 Level III-3 Global nutritional status118 Level II Rehabilitation Energy intake119 Level III-2 Protein intake119 Level II Residential aged care Fluid intake120 Level III-1 Energy and protein intake;121,122 weight status;123 physical function;123 quality of life; 123 and global nutritional status121 Level III-2 Community Weight status124 Level IV Global nutritional status125 NHMRC Grade of recommendation: B Feeding support provided by health care assistants may improve outcomes including: Level II Acute care Energy intake;126 body composition;126 use of antibiotics127 and life expectancy126 Rehabilitation No evidence located Residential aged care No evidence located Community No evidence located NHMRC Grade of recommendation: C A nutrition support team(c) may improve outcomes including: Level II Acute care Energy and protein intake128 Level IIl-1 Complications and costs129 Rehabilitation No evidence located Level IV Residential aged care Weight status130 Community No evidence located NHMRC Grade of recommendation: C Nutrition education provided on malnutrition to health professionals may improve outcomes: Acute care No evidence located Rehabilitation No evidence located Residential aged care No evidence located Level IIl-2 Community Global nutritional status131 NHMRC Grade of recommendation: D Multi-nutrient oral nutritional supplements (high energy and/or protein) may improve outcomes including: Level I Across settings Body composition,132,133 complications3 and life expectancy3,132,133 Level l Weight statusevidence of effect112 Level l Weight statusinconclusive3 Level ll Global nutritional status134 Level ll Energy intakeevidence of effect134 Level ll Energy intakeinconclusive135 Level III-2 Health care expenditure136 Level I Acute care Weight status;3,112,116 body composition;112,116 complications3,112 and pressure ulcers114 Level l Life expectancyevidence of an effect112,132,133 Level l Life expectancyinconclusive3 Level II Energy intake;137141 protein intake;139,141,142 global nutritional status143 and mood144 Level I Rehabilitation Complications and length of stay145 Level II Weight status;146 body composition146 and physical function147 Level IV Nutritional biochemistry; self-rated health and well-being148 Level I Residential aged care Weight status112 Level IV Energy intake149 Level I Community Weight status3,112 Level II Energy intake;150,151 body composition152 and physical function150,153 Level IV Cognition and quality of life154 [Aus] NHMRC Grade of recommendation: A S16 2009 The Author Journal compilation 2009 Dietitians Association of Australia

Practice Guidelines for the Nutritional Management of Malnutrition in Adult Patients Across the Continuum of Care

Dietary counselling(d) (with multi-nutrient oral nutritional supplements if deemed necessary) by a dietitian may improve outcomes including: Across settings No evidence located Level II Acute care Weight status and physical function155 Level IV Weight status and body composition156 Rehabilitation No evidence located Residential aged care No evidence located Community No evidence located NHMRC Grade of recommendation: C Enteral tube feeding(d) may improve outcomes including: Level I Across settings Complications111 Level l Acute care Weight status157 and length of stay158 Level I Risk of infectionevidence of effect158,159 Level l Risk of infectioninconclusive3 Level II Energy intake160 Level IV Body composition;161 nutritional biochemistry;161 and global nutritional status161,162 Rehabilitation No evidence located Residential aged care No evidence located Community No evidence located NHMRC Grade of recommendation: B Multi-nutrient oral nutritional supplements or enteral tube feeding in addition to exercise may improve outcomes including: Level II Acute care Weight status and nutritional biochemistry163 Level IV Physical function164,165 Level II Rehabilitation Weight status59 [Aus] Level II Residential aged care Energy intake and weight status166 Community No evidence located NHMRC Grade of recommendation: B Parenteral nutrition may improve outcomes including: Level I Acute care Risk of infection and life expectancy compared to no nutrition intervention159 Level I Life expectancy compared to EN, particularly delayed EN167 Level II Nutritional biochemistry168,169 Level IV Weight status170,171 and body composition170 Rehabilitation No evidence located Residential aged care No evidence located Community No evidence located NHMRC Grade of recommendation: B Individually prescribed nutritional support using mixed approaches (high energy diets +/- ONS; ETF; PN) may improve outcomes including: Level I Across settings Complications; risk of infection and length of stay111 Level II Acute care Energy intake172 and wound healing173 Level IV Weight status174 and nutritional biochemistry174 Rehabilitation No evidence located Level IV Residential aged care Weight status; body composition; nutritional biochemistry and physical function175 Community No evidence located NHMRC Grade of recommendation: C

2009 The Author Journal compilation 2009 Dietitians Association of Australia

S17

Nutrition & Dietetics 2009; 66 (Suppl. 3): S11S20

Recommendation Nutrition interventions can improve outcomes. Consideration should be given to the health care setting, resources, patient/client goals, requirements and preferences. NHMRC Grade of recommendation: BC

(a) Age, measures of body composition, nutritional biochemistry, global nutritional status (scores generated from two or more indicators of nutritional status), and other outcomes including physical function, vary across individual studies and readers are referred to study tables to determine measures used. (b) Studies evaluating food provision methods included strategies such as nutrient density, small portion sizes and improvements to the dining experience (eg. buffet style meals rather than pre-plated). (c) Nutrition support team interventions ranged from teams including a nurse and a dietitian to teams including nurses, a dietitian, speech and language therapists, caterers and occupational therapists. (d) Further evidence exists for certain patient groups [refer to Evidence Based Guidelines for the Nutritional Management of Patients Receiving Radiation Therapy].13 NB. Where NICE guidelines are referred to, only ndings from meta-analyses are included.3 ETF Enteral Tube Feed; ONS, High energy and protein multi-nutrient oral supplements; PN, Parenteral Nutrition. ,

Clinical question

3c: What are appropriate monitoring and outcome measures to demonstrate improved patient, clinical and cost outcomes?

Outcome measures Direct nutrition outcomes: Improving nutrition knowledge Suggested frequency of review of measure being monitored Inpatient: Daily initially for patient and team reducing to twice weekly as knowledge is gained3 Ambulatory: at least fortnightly13 Inpatient: Daily initially reducing to twice weekly when the patient/ resident is stable3 Ambulatory: minimum fortnightly dietitian contact13 Rationale or clarication Measure knowledge gained; behaviour change; adherence to plan.

Improved nutrient intake Energy Protein Fluid Improved nutrition anthropometry: Body weight

Monitor using direct observation and quantitative dietary intake methods especially of energy and protein.14 Monitor uid balance.176 Review progress towards nutrient goals; set criteria for commencing interventions such as high energy diets; ONS; ETF; PN.59 [Aus] Use calibrated equipment and standardised techniques and calculations where required. Ideally measure MAMC to take into account both body fat and muscle.175,177

MAMC Tricep skinfold thickness Improved score on validated global nutrition assessment tool Baseline and monthly MNA score134,143 PG-SGA score178

Inpatient: daily if concerns about uid status, otherwise weekly reducing to monthly3 Ambulatory: minimum fortnightly reducing to monthly; biannually as patient stabilises15 Baseline and monthly3

Global nutrition assessment tools can provide pre and post intervention comparisons so long as there is consistency in the application of the tool Many measures of nutritional biochemistry exist. Caution should be exercised in the interpretations of biochemistry particularly in the acute care setting; consideration should be given to the cost of testing and burden of testing to the patient.

Clinical and Health Status Outcomes Improved nutritional biochemistry Baseline then weekly3

S18

2009 The Author Journal compilation 2009 Dietitians Association of Australia

Practice Guidelines for the Nutritional Management of Malnutrition in Adult Patients Across the Continuum of Care

Prevention of pressure ulcers114

Patients at risk of developing pressure ulcers only: baseline/ admission and then weekly

Improved wound healing

Daily

Reduced infections and use of antibiotics Increased peak expiratory ow156 Decreased nausea, vomiting and/or diarrhea (from ONS and/or ETF) Patient-Centered Outcomes Improved quality of life, self rated health & well being

May be a suitable outcome measure for quality audits of the effectiveness of nutrition interventions Daily until problem resolves Daily until problem resolves

Consider a preventative nutrition intervention where there is a risk of pressure ulcers based on pressure ulcer risk tool e.g. Waterlow Pressure ulcer tool.114 Many tools are available; needs to be performed by an appropriately skilled health professional.154,173 Outcome needs to be monitored at the population level. To be performed by appropriate health professional. Intervene with early feeding where necessary. Review tolerance to formula/ feeding regimen to ensure achievement of goals.3,158 Use a culturally appropriate tool, e.g. Medical Outcomes Study 36-item Short-Form General Health Survey (SF-36) is commonly used.156 Culturally appropriate depression scales.144,179 Many measures of physical function exist, which may be used to monitor nutrition interventions. Tools require training, standardised techniques and calibrated equipment. Often, the measures may be undertaken in association with an appropriate health professional. For example, use the results of the Mini Mental State Examination (MMSE) tool.154 Outcome needs to be monitored at the population level.

Baseline and at the appropriate interval as per tool protocol

Improved mood Improved physical function Activities of Daily Living (eg; Katz index)147,155 Hand-grip strength

Baseline and at the appropriate interval as per tool protocol Baseline and monthly

Improved cognition

Baseline and at the appropriate interval as per tool protocol Hospital discharge, quarterly and yearly- audit health information datasets Yearly- survey of patients180

Improved life expectancy

Outcome needs to be monitored at the Patient satisfaction with nutrition population level. services provided by dietitians Healthcare utilisation and cost outcomes Reduced prevalence of Yearly-cross-sectional audit of Outcome needs to be monitored at malnutrition malnutrition prevalence the population level. Increased referrals of patients at Yearly-audit activity statistics risk of malnutrition to a dietitian Yearly-audit health information Reduced length of stay111 datasets Yearly-audit health information Reduced readmissions156 datasets Requires assistance from a Health Reduced costs11,136,176 Economist. Recommendation Choose standardised measures which change in a clinically meaningful way to demonstrate the outcomes of nutrition interventions. NHMRC Grade of recommendation: N/A

Note: The suggested frequency of review of the measures represents consensus opinion. MAMC, mid arm muscle circumference; MNA, mini nutritional assessment; High energy and protein multi-nutrient oral supplements; PG-SGA, Patient Generated- Subjective Global Assessment; PN, Parenteral Nutrition.

2009 The Author Journal compilation 2009 Dietitians Association of Australia

S19

Nutrition & Dietetics 2009; 66 (Suppl. 3): S11S20

Nutrition goals; intervention; monitoring practice tips: