Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

The Economic Impacts of Ecotourism

Enviado por

Shoaib MuhammadDescrição original:

Direitos autorais

Formatos disponíveis

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

The Economic Impacts of Ecotourism

Enviado por

Shoaib MuhammadDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

The Economic Impacts of Ecotourism

By Kreg Lindberg, PhD Lecturer, Charles Sturt University 3 November 1996 There are two related, but distinct, economic concepts in ecotourism: economic impact and economic value. This issues paper focusses on economic impact, which refers to the change in sales, income, jobs, or other parameter generated by ecotourism. A common ecotourism goal is the generation of economic benefits, whether they be profits for companies, jobs for communities, or revenues for parks. Ecotourism plays a particularly important role because it can create jobs in remote regions that historically have benefited less from economic development programs than have more populous areas. Even a small number of jobs may be significant in communities where populations are low and alternatives are few. This economic impact can increase political and financial support for conservation. Protected areas, and nature conservation generally, provide many benefits to society, including preservation of biodiversity, maintenance of watersheds, and so on. Unfortunately, many of these benefits are intangible. However, the benefits associated with recreation and tourism in protected areas tend to be tangible. For example, divers at a marine park spend money on lodging, food, and other goods and services, thereby providing employment for local and non-local residents. These positive economic impacts can lead to increased support for the protected areas with which they are associated. This is one reason why ecotourism has been embraced as a means for enhancing conservation of natural resources. Several studies in Australia and elsewhere have assessed the economic impacts of ecotourism. Predictably, the level of benefits varies widely as a result of differences in the quality of the attraction, access, and so on. In some cases, the number of jobs created will be low, but in rural areas even a few jobs can make a big difference. Still, ecotourism benefits should not be oversold, or there may be a backlash as reality fails to live up to expectations. The impacts of ecotourism, or any economic activity, can be grouped into three categories: direct, indirect, and induced. Direct impacts are those arising from the initial tourism spending, such as money spent at a restaurant. The restaurant buys goods and services (inputs) from other businesses, thereby generating indirect impacts. In addition, the restaurant employees spend part of their wages to buy

various goods and services, thereby generating induced impacts. Of course, if the restaurant purchases the goods and services from outside the region of interest, then the money provides no indirect impact to the region -- it leaks away. Figure 1 illustrates some of these impacts and leakages.

By identifying the leakages, or conversely the linkages within the economy, the indirect and induced impacts of tourism can be estimated. In addition, this information can be used to identify what goods are needed but are not being produced in the region, how much demand there is for such goods, and what the likely benefits of local production would be. This enables policy makers to determine priorities for developing inputs for use by the tourism or other industries. How, then, are these direct, indirect, and induced impacts to be estimated? For small areas with non-diverse economies, there are relatively few indirect and induced impacts, and there are relatively little data available for modeling these impacts. Therefore, surveys of visitors, residents, and/or businesses often are used to identify tourism's direct impacts. For larger areas, such as states or countries, economists have developed various techniques for estimating indirect and induced impacts, including computable general equilibrium (CGE) and input-output (IO) analysis. Examples

Driml and Common (see below for references) present the following data on 1991/1992 annual visitor expenditure at the following World Heritage Areas: Great Barrier Reef AU$776 million Wet Tropics AU$377 million Kakadu AU$122 million Uluru AU$38 million Tasmanian Wilderness AU$59 million Powell and Chalmers used input-output analysis to estimate that Dorrigo National Park in New South Wales contributed 7% of gross regional output and 8.4% of regional employment. Lindberg and Enriquez used resident surveys and input-output analysis to estimate

local and national economic impacts associated with tourism in Belize. National total (direct, indirect, and induced) impacts for 1992 were estimated at US$211 million in sales and US$41 million in personal income.

A common priority is to increase economic benefits, and the traditional approach is to attract more visitors. Given that negative impacts (environmental, experiential, sociocultural, and economic) correspond, to varying degrees, to visitor numbers, generally it is preferable to increase local benefits by: increasing spending per visitor; increasing backward linkages (reducing leakages); or increasing local participation in the industry. Spending per visitor can be increased through, for example, provision of handicrafts where such provision currently does not exist. In some cases, there may also be prospects for attracting higher-spending visitors. Backward linkages can be increased through greater use of local agricultural and other products. In order to increase backward linkages and local participation in the industry, it may be necessary to implement or expand capital availability and training programs. Economic impact analysis can provide valuable information when evaluating the costs and benefits of such programs. For more information and examples In an article for the Australian Journal of Environmental Management (volume 2, number 1, pages 19-29), Sally Driml and Mick Common provide data on visitor expenditure (direct impacts) and user fees collected at five World Heritage Areas. In their report for the NSW National Parks and Wildlife Service (Regional Economic Impact: Gibraltar Range and Dorrigo National Parks, 1995, available for $10 from NSW NPWS (02) 585 6333), Roy Powell and Linden Chalmers use input-output analysis to estimate the economic impacts of ecotourism at these national parks. In their report for WWF (US) (An Analysis of Ecotourism's Economic Contribution to Conservation and Development in Belize, 1994), Kreg Lindberg and Jerry Enriquez use resident surveys to estimate local economic impacts and input-output analysis to estimate national economic impacts of tourism.

In a presentation at the 1996 Tourism and Hospitality Research Conference ("Kate Fischer or Liz Hurley, Which Model Should I Use?"), Trevor Mules discusses various economic impact models. The proceedings are published by the Bureau of Tourism Research (06) 279 7264. The Australian Bureau of Statistics publishes Information Paper, Australian National Accounts, Introduction to Input-Output Multipliers, Catalogue No. 5246.0, Fax (06) 252 5380. If you have comments on this issues paper or want to add a relevant reference, please contact Kreg Lindberg.

Você também pode gostar

- Economic Impacts of Tourism: Bba-Ho&MDocumento51 páginasEconomic Impacts of Tourism: Bba-Ho&MKets Ch100% (1)

- Ecotourism in SagadaDocumento19 páginasEcotourism in SagadaDaryl Santiago Delos ReyesAinda não há avaliações

- Classification of EcotourismDocumento20 páginasClassification of EcotourismKleyr Sambrano AlmascoAinda não há avaliações

- Eco-Tourism and ArchitectureDocumento5 páginasEco-Tourism and ArchitectureShreesh JagtapAinda não há avaliações

- Angkor Heritage Tourism and The Issues of SustainabilyDocumento293 páginasAngkor Heritage Tourism and The Issues of Sustainabilymarlonbiu100% (1)

- Ecotourism PDFDocumento9 páginasEcotourism PDFcelineAinda não há avaliações

- The Influence of Context On Privacy Concern in Smart Tourism DestinationsDocumento12 páginasThe Influence of Context On Privacy Concern in Smart Tourism DestinationsGlobal Research and Development ServicesAinda não há avaliações

- Ecotourism Practices in Sri Lankan Eco ResortsDocumento12 páginasEcotourism Practices in Sri Lankan Eco ResortsDanielAinda não há avaliações

- Sustainable TourismDocumento78 páginasSustainable TourismAndre WibisonoAinda não há avaliações

- EcotourismDocumento4 páginasEcotourismYanesa ValdezAinda não há avaliações

- An Assessment of The Ecotourism Sector in The Municipality of OcampoDocumento9 páginasAn Assessment of The Ecotourism Sector in The Municipality of OcampoNerwin IbarrientosAinda não há avaliações

- Ecotourism Visitor Management Framework AssessmentDocumento15 páginasEcotourism Visitor Management Framework AssessmentFranco JocsonAinda não há avaliações

- Saving Marine Turtles A Strategy For Community-Based Ecotourism in The West Coast of Puerto Princesa CityDocumento33 páginasSaving Marine Turtles A Strategy For Community-Based Ecotourism in The West Coast of Puerto Princesa CityCorazon LiwanagAinda não há avaliações

- 4 IntraDocumento23 páginas4 IntraPaulo FlavierAinda não há avaliações

- EcotourismDocumento4 páginasEcotourismRomeo Caranguian Jr.Ainda não há avaliações

- EcotourismDocumento15 páginasEcotourismJayaraju VasudevanAinda não há avaliações

- Terminals: (Airports and Bus Terminal)Documento40 páginasTerminals: (Airports and Bus Terminal)Nicole NiderAinda não há avaliações

- Vigan Case StudyDocumento2 páginasVigan Case StudySanderVinciMalahayFuentesAinda não há avaliações

- Ecotourism Park ResearchDocumento127 páginasEcotourism Park ResearchKent AlfantaAinda não há avaliações

- Gastronomic Experience For Tourists-Oruro-BoliviaDocumento8 páginasGastronomic Experience For Tourists-Oruro-BoliviadevikaAinda não há avaliações

- Discuss The Concept of Tourism Carrying Capacit1Documento6 páginasDiscuss The Concept of Tourism Carrying Capacit1Moses Mwah MurayaAinda não há avaliações

- PARAMETRICISM: A Community Trading Center for Small-to-Medium EnterprisesDocumento59 páginasPARAMETRICISM: A Community Trading Center for Small-to-Medium EnterprisesLhen DaanAinda não há avaliações

- Assessment of The Effects of One Stop Service Centers in Service Delivery To Small and Medium Enterprise in Manufacturing Sector: The Case of Mekell City TigrayDocumento10 páginasAssessment of The Effects of One Stop Service Centers in Service Delivery To Small and Medium Enterprise in Manufacturing Sector: The Case of Mekell City TigrayInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyAinda não há avaliações

- Sustainable Tourism and Carrying Capacity in The Mediterranean Area PDFDocumento50 páginasSustainable Tourism and Carrying Capacity in The Mediterranean Area PDFWihno100% (2)

- EcotourismDocumento8 páginasEcotourismRachel DollisonAinda não há avaliações

- MCWS Ecotourism Management Plan, Final - LAC - 26dec2018 (Edited)Documento163 páginasMCWS Ecotourism Management Plan, Final - LAC - 26dec2018 (Edited)Robert P. Duquil100% (2)

- Sustainable Tourism For Biodiversity Conservation - El Nido ResortsDocumento29 páginasSustainable Tourism For Biodiversity Conservation - El Nido ResortsEnvironment Department, El Nido ResortsAinda não há avaliações

- Thesis Eco-Culture TourismDocumento192 páginasThesis Eco-Culture TourismArdian SyahAinda não há avaliações

- Enchante Kingdom PRELIMS IN LEISUREDocumento4 páginasEnchante Kingdom PRELIMS IN LEISUREAdie UAinda não há avaliações

- Sustainable Tourism TP OutputDocumento5 páginasSustainable Tourism TP OutputRose AnnAinda não há avaliações

- Architecture and Tourism The Case of Historic Preservations, Human Capital Development and Employment Creation in NigeriaDocumento15 páginasArchitecture and Tourism The Case of Historic Preservations, Human Capital Development and Employment Creation in NigeriaEditor IJTSRDAinda não há avaliações

- Sustainable Redevelopment of Canigao Island ResortDocumento11 páginasSustainable Redevelopment of Canigao Island ResortAlvin YutangcoAinda não há avaliações

- PLANS AND PLANNING FOR RESORT DEVELOPMENTDocumento2 páginasPLANS AND PLANNING FOR RESORT DEVELOPMENTNikki OloanAinda não há avaliações

- Sustainable Tourism Growth in BangladeshDocumento36 páginasSustainable Tourism Growth in BangladeshMuannis Mahmood100% (1)

- Resort Planning Development ConsiderationsDocumento37 páginasResort Planning Development ConsiderationsJayarfernAinda não há avaliações

- Eco Business ParkDocumento10 páginasEco Business ParkJavier HerrerosAinda não há avaliações

- Arroceros Forest ParkDocumento2 páginasArroceros Forest ParkAika CardenasAinda não há avaliações

- Airport PresentationDocumento21 páginasAirport PresentationQuennie Grace Moreno TabayagAinda não há avaliações

- Understanding Heritage Aditi Sharma 181026Documento4 páginasUnderstanding Heritage Aditi Sharma 181026Aditi SharmaAinda não há avaliações

- Perceived Impacts of Tourism in A Protected Landscape: The Case of Brooke's Point and Quezon, Mt. Mantalingahan Protected LandscapeDocumento158 páginasPerceived Impacts of Tourism in A Protected Landscape: The Case of Brooke's Point and Quezon, Mt. Mantalingahan Protected LandscapeLovella Anne JoseAinda não há avaliações

- Lakbay Aral Sy 2015-2016 PDFDocumento10 páginasLakbay Aral Sy 2015-2016 PDFJeth MagdaraogAinda não há avaliações

- Tourism Development Plan of Camalaniugan, Cagayan: Outline: I. Tourism ProfileDocumento2 páginasTourism Development Plan of Camalaniugan, Cagayan: Outline: I. Tourism ProfileleeedeeemeeeAinda não há avaliações

- Philippine EcotourismDocumento97 páginasPhilippine EcotourismJericsson Isaac C. Lawrence100% (1)

- Agritourism: Alternative For Sustainable Rural DevelopmentDocumento21 páginasAgritourism: Alternative For Sustainable Rural DevelopmentDaniel LiensAinda não há avaliações

- Almodiente Thesis 1 4Documento67 páginasAlmodiente Thesis 1 4ScarletAinda não há avaliações

- Ecotourism ManualDocumento254 páginasEcotourism ManualJeavelyn CabilinoAinda não há avaliações

- Beach Resort Concept ProposalDocumento5 páginasBeach Resort Concept ProposalarianeAinda não há avaliações

- Sense of Place QuestionnaireDocumento1 páginaSense of Place QuestionnaireKaii Beray De AusenAinda não há avaliações

- Characterizing Campus Open Spaces at UP DilimanDocumento18 páginasCharacterizing Campus Open Spaces at UP DilimanAndroAinda não há avaliações

- ECO-FARM RESORT IN LAOAC THESIS PROPOSALDocumento41 páginasECO-FARM RESORT IN LAOAC THESIS PROPOSALDAWFWFAinda não há avaliações

- Marketing Practices of Resorts in Cuyapo, Nueva Ecija: Implications To Business and Social StudiesDocumento7 páginasMarketing Practices of Resorts in Cuyapo, Nueva Ecija: Implications To Business and Social StudiesIjaems JournalAinda não há avaliações

- Case Study Kerala TourismDocumento9 páginasCase Study Kerala Tourismurmi_18100% (1)

- Tourists Expectations Regarding Agritourism - Empirical EvidencesDocumento10 páginasTourists Expectations Regarding Agritourism - Empirical EvidencesDr. Vijay KumbharAinda não há avaliações

- Proposed Donsol Marine Center to Protect Whale SharksDocumento314 páginasProposed Donsol Marine Center to Protect Whale SharksKC PanerAinda não há avaliações

- Role of Visitor Attraction in TourismDocumento36 páginasRole of Visitor Attraction in Tourismparaway100% (4)

- Relationship Between Planned and Unplanned Land Uses and Their Implications On Future Development. A Case Study of Industrial Division in Mbale MunicipalityDocumento66 páginasRelationship Between Planned and Unplanned Land Uses and Their Implications On Future Development. A Case Study of Industrial Division in Mbale MunicipalityNambassi MosesAinda não há avaliações

- Barbados Agro-tourism Inventory ReportDocumento72 páginasBarbados Agro-tourism Inventory ReportRaymond Villamante AlbueroAinda não há avaliações

- Ecotourism ResearchDocumento6 páginasEcotourism ResearchArpanAinda não há avaliações

- Shantel WIlliams - Impact of Tourism On Economy Culture and EnvironmentDocumento7 páginasShantel WIlliams - Impact of Tourism On Economy Culture and EnvironmentShantel WilliamsAinda não há avaliações

- Cell # (+92) 345 787 46 74 - Muhammad Shoaib GSP Officer, Trade Development Authority of PakistanDocumento3 páginasCell # (+92) 345 787 46 74 - Muhammad Shoaib GSP Officer, Trade Development Authority of PakistanShoaib MuhammadAinda não há avaliações

- Muhammad Shoaib ResumeDocumento3 páginasMuhammad Shoaib ResumeShoaib MuhammadAinda não há avaliações

- Strategic Planning Assignment SolutionsDocumento3 páginasStrategic Planning Assignment SolutionsShoaib MuhammadAinda não há avaliações

- Muhammad Shoaib: Personal DataDocumento2 páginasMuhammad Shoaib: Personal DataShoaib MuhammadAinda não há avaliações

- Nike SWOT Analysis and Marketing StrategyDocumento15 páginasNike SWOT Analysis and Marketing Strategyumarulez100% (2)

- Assignment Solutions, Assignment Solutions,, Assignment Solutions,, Assignment SolutionsDocumento44 páginasAssignment Solutions, Assignment Solutions,, Assignment Solutions,, Assignment SolutionsShoaib MuhammadAinda não há avaliações

- Dissertation Chapter 4Documento18 páginasDissertation Chapter 4Shoaib MuhammadAinda não há avaliações

- International Human Resource Management 2Documento15 páginasInternational Human Resource Management 2Shoaib MuhammadAinda não há avaliações

- Assignment Solutions Relationship Between Capital Structure and PerformanceDocumento19 páginasAssignment Solutions Relationship Between Capital Structure and PerformanceShoaib MuhammadAinda não há avaliações

- Vodafone Strategic DevelopmentDocumento2 páginasVodafone Strategic DevelopmentShoaib MuhammadAinda não há avaliações

- 1B. MarketingDocumento10 páginas1B. MarketingShoaib MuhammadAinda não há avaliações

- Muhammad ShoaibDocumento2 páginasMuhammad ShoaibShoaib MuhammadAinda não há avaliações

- Adult Literacy in Pakistan (Muhammad Shoaib) Adult EducationDocumento10 páginasAdult Literacy in Pakistan (Muhammad Shoaib) Adult EducationShoaib MuhammadAinda não há avaliações

- Abbey NationalDocumento25 páginasAbbey NationalShoaib MuhammadAinda não há avaliações

- Motivation TheoriesDocumento22 páginasMotivation TheoriesslixsterAinda não há avaliações

- RSPN DBP PostsDocumento1 páginaRSPN DBP PostsShoaib MuhammadAinda não há avaliações

- 2002 FinalDocumento13 páginas2002 FinalShoaib MuhammadAinda não há avaliações

- McdonaldsDocumento10 páginasMcdonaldssree2u4Ainda não há avaliações

- Organizational Learning: Hafiz Muhammad Naeem UddinDocumento8 páginasOrganizational Learning: Hafiz Muhammad Naeem UddinShoaib MuhammadAinda não há avaliações

- CV for Accounts JobDocumento1 páginaCV for Accounts JobShoaib MuhammadAinda não há avaliações

- Anthropology TourismDocumento21 páginasAnthropology TourismButik AdistiAinda não há avaliações

- Guideline-Minimum Design RequirementsDocumento1 páginaGuideline-Minimum Design RequirementsOhoud KamalAinda não há avaliações

- Good Essay Writing - A Holiday I Would Never Forget - SPM English Essay WritingDocumento2 páginasGood Essay Writing - A Holiday I Would Never Forget - SPM English Essay Writingstam100% (1)

- Masskara Festival - Google SearchDocumento1 páginaMasskara Festival - Google SearchJarell BandrangAinda não há avaliações

- Transportation Sector Write UpDocumento2 páginasTransportation Sector Write Upeipem1Ainda não há avaliações

- 3 Macro Tourism Travel Tour PPPDocumento80 páginas3 Macro Tourism Travel Tour PPPVince L. LanidaAinda não há avaliações

- Innkeepers Act 1952Documento22 páginasInnkeepers Act 1952Fuo NienAinda não há avaliações

- Housekeeping Presentation: Challenges Faced by Housekeeping in A Beach Resort HotelDocumento12 páginasHousekeeping Presentation: Challenges Faced by Housekeeping in A Beach Resort Hotelharshal kushwahAinda não há avaliações

- In Pursuit of Alaska: An Anthology of Travelers' Tales, 1879-1909Documento29 páginasIn Pursuit of Alaska: An Anthology of Travelers' Tales, 1879-1909University of Washington PressAinda não há avaliações

- Factors in Uencing The Destination Image of Kuching Waterfront: A Tourist PerspectiveDocumento16 páginasFactors in Uencing The Destination Image of Kuching Waterfront: A Tourist PerspectivemilamoAinda não há avaliações

- Itm-Fhrai - 2013Documento40 páginasItm-Fhrai - 2013sudhanshujha2007Ainda não há avaliações

- Eng Tugas Wmk-Siska NurdeianaDocumento24 páginasEng Tugas Wmk-Siska NurdeianaariyanighisaAinda não há avaliações

- Basic Facts of KazakhstanDocumento2 páginasBasic Facts of KazakhstanIsrael AsinasAinda não há avaliações

- Prospects of Mountaineering and Trekking Tourism in Nepal (Please Comment After Read This)Documento32 páginasProspects of Mountaineering and Trekking Tourism in Nepal (Please Comment After Read This)Suman Babu Panta70% (10)

- Burlington 4Documento7 páginasBurlington 4Tudor AnaAinda não há avaliações

- ECONOMICSDocumento5 páginasECONOMICSSavitha Bhaskaran50% (4)

- Functions of Travel Management CompanyDocumento26 páginasFunctions of Travel Management CompanyVicente VicenteAinda não há avaliações

- HRP - HotelDocumento60 páginasHRP - HotelkartikAinda não há avaliações

- Redrow Millfields Host BrochureDocumento42 páginasRedrow Millfields Host BrochuremnawazAinda não há avaliações

- Evidence My Dream VacationDocumento5 páginasEvidence My Dream VacationJeison PalAciosAinda não há avaliações

- Allysea Marie R. LopezDocumento3 páginasAllysea Marie R. LopezAllysea LopezAinda não há avaliações

- Guideline For Green HotelDocumento66 páginasGuideline For Green HotelsufijinnAinda não há avaliações

- Private Pools and ResortsDocumento8 páginasPrivate Pools and ResortsJoanne Charmaine Ibana LaoagAinda não há avaliações

- ClassifiedrecordsDocumento23 páginasClassifiedrecordsChetana SJadigerAinda não há avaliações

- Both - Neither - EitherDocumento2 páginasBoth - Neither - EitherPaquiAinda não há avaliações

- Agriculture 12 01586 v2Documento15 páginasAgriculture 12 01586 v2Ying SunAinda não há avaliações

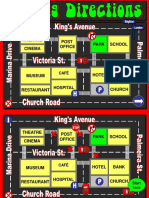

- Asking and Giving DirectionsDocumento12 páginasAsking and Giving DirectionsPelita BangunAinda não há avaliações

- Resort Improvement Newsletter | October 2014Documento8 páginasResort Improvement Newsletter | October 2014Aneed KasparovAinda não há avaliações

- Poslovni Engleski Jezik B2 / Pitanja Za UsmeniDocumento4 páginasPoslovni Engleski Jezik B2 / Pitanja Za Usmenikiki09062008Ainda não há avaliações

- Dương Nguyễn Hải Linh - Reflection Paper - HSTM4462Documento8 páginasDương Nguyễn Hải Linh - Reflection Paper - HSTM4462Linh DươngAinda não há avaliações