Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

Introduction To Vol. 3, No. 3-4: "The Return of The Uncanny" Michael Arnzen University of Oregon

Enviado por

Angela NdalianisDescrição original:

Título original

Direitos autorais

Formatos disponíveis

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Introduction To Vol. 3, No. 3-4: "The Return of The Uncanny" Michael Arnzen University of Oregon

Enviado por

Angela NdalianisDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Introduction to Vol. 3, No.

3-4: "The Return of the Uncanny" Michael Arnzen University of Oregon

As this double issue of Paradoxa attests, "The Uncanny"[1] is enjoying an international resurgence of critical interest. Several of the contributors to this edition have already written (or are currently working on) books and articles which address the subject directly. In the past few years, other journals in the humanities have run special issues on the aesthetic conventions of the uncanny: from the Journal of the Fantastic in the Arts (on "the double"), to Research in Phenomenology (on "uncanny architecture"), to Angelaki (on "home and family" - an issue that also includes the first English translation of Ernst Jentsch's essay, "On the Psychology of the Uncanny," the inspiration for Freud's "Das Unheimliche"). Over the last decade a number of significant studies of the uncanny have emerged from vastly different disciplines: Terry Castle's The Female Thermometer: 18th Century Culture and the Invention of the Uncanny (1995); Anthony Vidler's The Architectural Uncanny (1994); Hal Foster's Compulsive Beauty (1993); Gordon Slethaug's The Play of the Double in Postmodern American Fiction (1993); Julia Kristeva's Strangers to Ourselves (1991), and Paul Coates' The Double and the Other (1988), to mention just a handful of the most notable titles. Even the latest edition of the PMLA (112.5) included an article by Robin Lydenberg on "Freud's Uncanny Narratives," which makes the audacious but persuasive claim that "the most essential quality of narrative is uncanniness" (1073). One might say that this is not only the "century of the uncanny" (to quote James Winchell's fine contribution to this volume), but also a century of uncanny scholarship - a century of heightened self-awareness and self-criticism, appropriate for a time when we are incessantly confronted with the sublime horror of our cultural past, and a time which seems to be turning progressively more "strange" and yet hauntingly more "familiar" as we stream toward the grand end of the second millennium. It is fitting that our interest in the uncanny should resurface at a time when literary critics seem to have finally settled onto that bed of nails we call "postmodern theory." The very term, "postmodern," contains and anticipates the immanent return of the "modern," which always threatens to reappear like Freud's uncanny "return of the repressed" (and this is why Lyotard reminds us that "'Post modern' would have to be understood according to the paradox of the future (post) anterior (modo)" (81)). The uncanny, if understood to be a state of paramnesia, or a subjective flux akin to dj-vu, structurally mimics Lyotard's linguistic paradox - past and present become confused in an experience of the uncanny just as they do in Baudrillard's "switching screen" of postmodern schizophrenic

consciousness. This is not to say that the uncanny is necessarily an issue of postmodern theory or today's culture alone - indeed, for a century of scholars, the uncanny has been a particularly modernist issue, because it shares the same concerns as that consummate modernist thinker, Freud, in his famously unsettled essay on the topic, "Das Unheimliche." Modernity and postmodernity share similar, yet different anxieties - the uncanny gives us a way of thinking about the interrelationship of both. The dopplegnger and the automaton haunted the moderns, for example, while clones and techno-human cyborgs haunt us today. The majority of the essays in this issue of Paradoxa fall somewhere between modernist and postmodernist concerns. But it should be noted that the disruption which the uncanny signals (a disruption of time; a fracturing, splitting, or doubling of subjectivity; a deconstructive repetition-with-a-difference) resonates deeply with contemporary philosophers who have moved beyond purely psychoanalytic or aesthetic issues. Indeed, Anthony Vidler believes that the "selfconscious ironization of modernism by postmodernism" has construed a "postmodern uncanny" (9); Jacques Derrida seems obsessed with the uncanny in his deconstruction of language and treatment of utterance as "always already" invested with meaning; Frederic Jameson describes the penchant for pastiche and nostalgia in late capitalist culture generally as an uncanny "waning of affect"; Jean Baudrillard's "simulacrum" shares much with traditional theories of the "double"; Hlne Cixous has even performed a feminist deconstructive reading of Freud's essay on the uncanny itself. Indeed, it seems as though that major strand of "indeterminacy" in postmodern theory which Ihab Hassan has termed "The Unrepresentable" is entirely preoccupied with the uncanny in many implicit and explicit ways (168-70). Contemporary criticism is not merely fascinated by the uncanny; such work reflects an uncanny world-view which many non-academics share. As Alice Jardine so eloquently puts it, [Postmodern theorists] have denaturalized the world that humanism naturalized, a world whose anthro-pology and anthro-centrism no longer make sense. It is a strange new world they have invented, a world that is unheimlich. And such strangeness has necessitated speaking and writing in new and strange ways. (24) The writers in this issue of Paradoxa all excel at exploring this "strange new world" as it has been mapped out in the century of literature, film, and culture since Freud. And while not all of the essays in this volume should be characterized as "postmodern theory," they all address the philosophical underpinnings of the uncanny in sophisticated and intriguing ways, in "new and strange ways," and from a variety of contemporary perspectives which significantly inform our understanding of today's anxieties, ideologies, and desires. One "new and strange way" of experiencing life in the 20th century has been through that relatively young medium, the "motion picture." Literally embodying the uncanny in that its technology animates a series of inanimate still pictures, the cinematic eye has become a metaphor for subjectivity - from "mindscreens" to the "male gaze" - and we haven't "looked" at the world in the same way since its emergence. Indeed, film could be called the artistic medium of this century, and the cinema (having recently celebrated its centenary) is now embraced as an imporant and serious discipline of aesthetic study. Consistent with this attention, most of the articles in this issue of Paradoxa explore the relationship of the uncanny to film. William Paul's historical essay, "Uncanny Theater," traces early film practice to show how both theater architecture and the subject matter of primitive films attempted to contain the uncanny possibilities of the

cinema, resulting in many of the strange conventions (screening and narrative) which remain with us today. Lesley Stern contributes a study of the cinematic motif of the somersault by somersaulting through her own screen memories as well as those of film history, jaunting from Scorsese pictures and Blade Runner all the way back to films of the 1900's and back again, spinning an insightful phenomenological treatment of the uncanny along the way. Martin Norden, in "The Uncanny Film Image of the Obsessive Avenger," likewise traces an uncanny motif through cinematic history (albeit more orthodox in its Freudian approach to the uncanny), reading film narrative's continued fascination with the handicapped through castration anxiety, and all that that implies. Where film history is not at issue, specific movies and cinematic genres which foreground the uncanny are addressed by the critics in these pages, raising issues of particular significance to scholars today. Elizabeth Coffman brings a post-colonial perspective to the uncanny and its relationship to race issues in her essay on Josephine Baker and that African-American star's vehicle, Princess Tam Tam. In "Double Reading/Reading Double," Anneleen Masschelein reads the uncanny function of "suture theory" in the independent film ironically entitled Suture, alongside Hlne Cixous' important essay on Freud's "Das Unheimliche" ("Fiction and its Phantoms"). Masschelein generates a surprisingly cohesive comparison between film and philosophy in order to both critique and trace the virtues of a "poetics of reading" grounded in uncanny subjectivity. Horror films, naturally, are also addressed in this issue. Isabel Pinedo looks at the uncanny film form of splatter movies and the function of what she terms "recreational terror" in her contribution, "The Wet Death and the Uncanny." Her essay bridges the assumed gap between "body horror" and the more sublime concerns of the uncanny. Some would argue, however, that the horror film as a genre has been exhausted, and is currently experiencing its own "wet death" in the eyes of the public Steven Schneider offers some clues as to why this genre is waning in his "Uncanny Realism and the Decline of the Modern Horror Film." An interview with film genre critic Barry Grant also provides us not only with myriad ways of thinking of the uncanny in relation to cinematic genres, but also in its latest manifestation in the recent "yuppie horror" cycle of films. Gesa Mackenthun turns to horror literature - particularly Stephen King novels- in her essay, "Haunted Real Estate." She traces how U.S. authors and filmmakers have treated Native American burial grounds as uncanny, uncovering an American "occlusion of colonial dispossession" (a disavowal of U.S. colonization) in the process. Also focusing on contemporary horror literature, Sylvia Kelso offers "The Postmodern Uncanny: or, Establishing Uncertainty" which not only traces the presence of the uncanny in vampire novels written by women, but contributes significantly to our understanding of postmodernity, body theory, and gender issues via the uncanny. Maria Aline Ferreira looks at specific representations of motherhood - which has a long ideological history of being aligned with the uncanny - in her close, perceptive reading of Angela Carter's book, The Passion of New Eve. Concerned not so much with motherhood as with childhood, Karen Coats presents a compelling analysis of the way children's literature "underwrites" the uncanny in psychosexual development. George Aichele contributes an essay on the uncanny as it functions in the literature (and theory) of postmodern fantasy, culminating in a close reading of Kafka's inherently uncanny story, "The Metamorphosis." James Winchell's "Century of the Uncanny" considers the centrality of the uncanny in the work of both Borges and William James, uncovering the crucial philosophical questions they raise for literary study. Altogether, the uncanny just may be "the most essential quality of narrative," as Lydenberg put it, and as all these articles on the

uncanny and literature reveal. An interview with 18th century scholar Terry Castle situates these literary concerns within a broader context that will enlighten as it entertains. Several pieces in this issue trace the uncanny in pop culture and the contemporary consciousness. Scott McQuire's "The Uncanny Home" begins with a profound reading of Bill Gates' dream house, and generates an insightful analysis of how the uncanny is invested in modern conceptions of space - which has become vastly interpolated by new technologies, including television. Nancy Batty reads the uncanny through that "unruly" television icon, Roseanne (a.k.a. Roseanne Arnold/Barr), revealing not only what that woman/character means for feminism, but also for television narrative and its contemporary audience. Shiela Kunkle provides a reading of postmodern museum art by an artist of the MTV generation, in an articulate, semi-autobiographical reading of the uncanny as it appears not only in one shocking exhibit, but also in the psychoanalytic theories of Lacan, Ziz#ek and Kristeva. And finally I have taken a look at the oddly uncanny objects clustering around the supermarket checkout stand - bar code scanners, "Double"-mint gum, the Weekly World News - in an attempt to "update" how we think about the uncanny, particularly in terms of the anxiety-ridden confrontation between the consumers and producers of mass culture. This is a "double" issue in every sense of the word. The scope of this issue should speak for itself (and isn't it uncanny that it does!). The uncanny has a significant, wide-ranging presence in our culture, and the tradition of its scholarship lends us an important way of thinking about the history of representation at the turn of the twentieth century. The uncanny is "a concept whose entire denotation is a connotation" (Cixous 528), and therefore it is also a very complicated and problematic subject. As anyone who has grappled with the uncanny knows, das Unheimliche is an enigmatic subjective experience, one which escapes language and yet is so intimately bound to its structure. The uncanny resists reason. And it is relatively easy to over-generalize the uncanny, to either see the "strangely familiar" everywhere or to universalize its foundation in the psyche. It is also quite easy to fall prey to the mise en abime of the uncanny's paradoxical nature, spinning one's wheels in never-ending contradictions and digging ever-so-deeper into a pit of ponderous theory. We applaud each writer in this issue for making a very difficult topic accessible, and for being so amenable to collaborative thinking during the editorial process. I would also like to thank those who worked behind-the-scenes on this issue ("all that should have remained secret, but has come to light"): Vivian Sobchack, Lance Olsen, Mark Ingram, Hamida Bosmajian, Beth Rapp Young, Kathleen Karlyn, David Sandner, Kate Sullivan, Daria Penta, Bennett Lovett-Graff, Sylvia Kelso, Renate Arnzen, Gemma Connolly, colleagues from the ICFA-18, and many others. I close with a kind wish for the reader, in the words of Jean Epstein, echoed by Lesley Stern: may you have "a strange and unexpected meeting with yourself" in these pages. Notes 1 Almost every author in this issue provides an operational definition of this term, whose meaning is multifaceted, but generally refers to an experience (either subjective or textual) of the "strangely familiar." For a short course in "Das Unheimliche" ("the uncanny" - literally, the "unhome-like") as it appears in Freud's

foundational essay on the topic, review the nice bulleted list in Lesley Stern's article, "I Think Therefore I ... Somersault" in this issue. Works Cited Angelaki 2.1 (1996). Baudrillard, Jean. "The Ecstasy of Communication." In The Anti-Aesthetic: Essays on Postmodern Culture. Ed. Hal Foster. Seattle, WA: Bay Press, 1983. 126-33. Castle, Terry. The Female Thermometer: Eighteenth-Century Culture and the Invention of the Uncanny. New York: Oxford UP, 1995. Cixous, Hlne. "Fiction and Its Phantoms: A Reading of Freud's Das Unheimliche." New Literary History 7.3 (Spring 1976): 525-48. Coates, Paul. The Double and the Other: Identity as Ideology in Post-Romantic Fiction. New York: St. Martin's Press, 1988. Derrida, Jacques. Dissemination. Trans. Barabara Johnson. Chicago: U of Chicago P, 1981. Foster, Hal. Compulsive Beauty. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1993. Freud, Sigmund. "The 'Uncanny.'" In Sigmund Freud: Collected Papers (Vol. 4). Trans. Joan Riviere. New York: Basic Books, Inc., 1959. 368-407. Hassan, Ihab. The Postmodern Turn: Essays in Postmodern Theory and Culture. Columbus, OH: Ohio State UP, 1987. Jameson, Fredric. Postmodernism, or, The Cultural Logic of Late Capitalism. Durham: Duke UP, 1991. Jardine, Alice. Gynesis: Configurations of Woman and Modernity. Ithaca, NY: Cornell UP, 1985. Jentsch, Ernst. "On the Psychology of the Uncanny." Trans. Forbes Morlock. Angelaki 2.1 (1996). Journal of the Fantastic in the Arts 6.2/3 (1995). Kristeva, Julia. Strangers To Ourselves. Trans. Leon S. Roudiez. New York: Columbia UP, 1991. Lydenberg, Robin. "Freud's Uncanny Narratives." PMLA 112.4 (Oct 1997): 1072-86. Lyotard, Jean-Franios. The Postmodern Condition: A Report on Knowledge. Trans. Geoff Bennington and Brian Massumi. Theory and History of Lit. 10. Minneapolis, MN: U of Minnesota P, 1993. Research in Phenomenology 22 (1992) Slethaug, Gordon E. The Play of the Double in Postmodern American Fiction. Carbondale: Southern Illinois UP, 1993. Vidler, Anthony. The Architectural Uncanny: Essays in the Modern Unhomely. Cambridge: MIT Press, 1994.

Copyright 1997 Michael A. Arnzen.

Return to Paradoxa

Você também pode gostar

- Scoring Incredible FuturesDocumento50 páginasScoring Incredible FuturesJOSE ANTONIO HERNANDEZ VERAAinda não há avaliações

- Scoring Incredible Futures: Science - Fiction Screen Music, and "Postmodernism" As Romantic EpiphanyDocumento35 páginasScoring Incredible Futures: Science - Fiction Screen Music, and "Postmodernism" As Romantic EpiphanyJorge GuardaminoAinda não há avaliações

- Absurd in Wole SinkaDocumento27 páginasAbsurd in Wole SinkaAchmad LatifAinda não há avaliações

- Postmodern LiteratureDocumento9 páginasPostmodern LiteratureStoica Villialina100% (1)

- Postmodernism Lecture WordDocumento6 páginasPostmodernism Lecture WordSky Walker100% (1)

- Postmodern LiteratureDocumento10 páginasPostmodern LiteraturemnazAinda não há avaliações

- Postmodern LiteratureDocumento10 páginasPostmodern Literatureoanatripa100% (1)

- Postmodern LiteratureDocumento14 páginasPostmodern LiteratureAly Fourou BaAinda não há avaliações

- Hochberg Asj Spring2018 Article PDFDocumento24 páginasHochberg Asj Spring2018 Article PDFمحمودحسنيAinda não há avaliações

- Małgorzata Stępnik, Outsiderzy, Mistyfikatorzy, Eskapiści W Sztuce XX Wieku (The Outsiders, The Mystifiers, The Escapists in 20th Century Art - A SUMMARY)Documento6 páginasMałgorzata Stępnik, Outsiderzy, Mistyfikatorzy, Eskapiści W Sztuce XX Wieku (The Outsiders, The Mystifiers, The Escapists in 20th Century Art - A SUMMARY)Malgorzata StepnikAinda não há avaliações

- Postmodernism and SlasherDocumento13 páginasPostmodernism and Slashercherry_booom100% (2)

- Heading for the Scene of the Crash: The Cultural Analysis of AmericaNo EverandHeading for the Scene of the Crash: The Cultural Analysis of AmericaAinda não há avaliações

- Stam - Sample Chapter - Literature Through FilmDocumento42 páginasStam - Sample Chapter - Literature Through FilmPablo SalinasAinda não há avaliações

- Postmodern Literature and The Question of Dehumanization in Dystopia: From The Optimistic Old To The Pessimistic NoveltyDocumento14 páginasPostmodern Literature and The Question of Dehumanization in Dystopia: From The Optimistic Old To The Pessimistic Noveltychahinez bouguerra100% (1)

- Postmodern LiteratureDocumento9 páginasPostmodern LiteraturejavedarifAinda não há avaliações

- Contemporary Gothic and Horror Film: Transnational PerspectivesNo EverandContemporary Gothic and Horror Film: Transnational PerspectivesAinda não há avaliações

- A Unique Loneliness The Existential Impulse in Art of The FortiesDocumento7 páginasA Unique Loneliness The Existential Impulse in Art of The FortiesSandra KastounAinda não há avaliações

- Scenes of the Obscene: The Non-Representable in Art and Visual Culture, Middle Ages to TodayNo EverandScenes of the Obscene: The Non-Representable in Art and Visual Culture, Middle Ages to TodayAinda não há avaliações

- Science Fiction: the Evolutionary Mythology of the Future: Volume Two: the Time Machine to MetropolisNo EverandScience Fiction: the Evolutionary Mythology of the Future: Volume Two: the Time Machine to MetropolisAinda não há avaliações

- Literary Genres: Ap English Literature & CompositionDocumento13 páginasLiterary Genres: Ap English Literature & CompositionMrsBrooks1100% (1)

- Unit4 PDFDocumento14 páginasUnit4 PDFUma BhushanAinda não há avaliações

- Chronotopes of the Uncanny: Time and Space in Postmodern New York Novels. Paul Auster's »City of Glass« and Toni Morrison's »Jazz«No EverandChronotopes of the Uncanny: Time and Space in Postmodern New York Novels. Paul Auster's »City of Glass« and Toni Morrison's »Jazz«Nota: 5 de 5 estrelas5/5 (1)

- The Washington Post Pulitzers: Phil Kennicott, CriticismNo EverandThe Washington Post Pulitzers: Phil Kennicott, CriticismAinda não há avaliações

- O Xango de Baker Street O Xango de Baker Street PDFDocumento11 páginasO Xango de Baker Street O Xango de Baker Street PDFherve zenaAinda não há avaliações

- Wasteland Modernism: The Disenchantment of MythNo EverandWasteland Modernism: The Disenchantment of MythAinda não há avaliações

- Self, World, and Art in The Fiction of John FowlesDocumento30 páginasSelf, World, and Art in The Fiction of John FowlesEvan PenningtonAinda não há avaliações

- The Modern Myths: Adventures in the Machinery of the Popular ImaginationNo EverandThe Modern Myths: Adventures in the Machinery of the Popular ImaginationNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (6)

- "Did You Smile With Her at The End?" - Performative Spectatorship in Midsommar and The Wicker ManDocumento14 páginas"Did You Smile With Her at The End?" - Performative Spectatorship in Midsommar and The Wicker ManBriti BhattacharyyaAinda não há avaliações

- Still Life: A User's Manual: Narrative May 2002Documento17 páginasStill Life: A User's Manual: Narrative May 2002Daisy BogdaniAinda não há avaliações

- In The Post-Modernist FiliationDocumento8 páginasIn The Post-Modernist FiliationMia AmaliaAinda não há avaliações

- Future Fiction: New Dimensions in International Science FictionNo EverandFuture Fiction: New Dimensions in International Science FictionAinda não há avaliações

- Reading MonstersDocumento11 páginasReading MonstersVíctor PueyoAinda não há avaliações

- (Modern American Literature) Pynchon, Thomas - Smith, Evans Lansing - Pynchon, Thomas - Thomas Pynchon and The Postmodern Mythology of The Underworld-Peter Lang Publishing Inc (2013) PDFDocumento355 páginas(Modern American Literature) Pynchon, Thomas - Smith, Evans Lansing - Pynchon, Thomas - Thomas Pynchon and The Postmodern Mythology of The Underworld-Peter Lang Publishing Inc (2013) PDFPedro LopezAinda não há avaliações

- MAP Module 3Documento6 páginasMAP Module 3Minh Quang DangAinda não há avaliações

- Unit-2 Postmodernism The BasicsDocumento6 páginasUnit-2 Postmodernism The BasicsAbhiram P PAinda não há avaliações

- The Novel As An AbsenceDocumento17 páginasThe Novel As An AbsenceZedarAinda não há avaliações

- Józsa István - Kortárs Művészet: Immortal Literature: Film Adaptations and Interpretations of Oscar Wilde'SDocumento19 páginasJózsa István - Kortárs Művészet: Immortal Literature: Film Adaptations and Interpretations of Oscar Wilde'SDeeJay MussexAinda não há avaliações

- Ivar Kreuger and Jeanne de la Motte: Two Plays by Jerzy W. TepaNo EverandIvar Kreuger and Jeanne de la Motte: Two Plays by Jerzy W. TepaAinda não há avaliações

- Gale Researcher Guide for: British Creative Nonfiction: The Development of the GenreNo EverandGale Researcher Guide for: British Creative Nonfiction: The Development of the GenreAinda não há avaliações

- Louise Milne The Broom of The System, Tramway, Glasgow, 2008Documento7 páginasLouise Milne The Broom of The System, Tramway, Glasgow, 2008Louise MilneAinda não há avaliações

- Nietzschean Nihilism and Alternative ModernitiesDocumento14 páginasNietzschean Nihilism and Alternative ModernitiesAbhinaba ChatterjeeAinda não há avaliações

- Pasolinis Decameron and Teaching The Middle AgesDocumento6 páginasPasolinis Decameron and Teaching The Middle AgesTara BurgessAinda não há avaliações

- Ionescos Rhinoceros and The Menippean TraditionDocumento15 páginasIonescos Rhinoceros and The Menippean TraditionAndreea JosefinAinda não há avaliações

- Badiou - Manifesto On AffirmationismDocumento8 páginasBadiou - Manifesto On AffirmationismÖzlem AlkisAinda não há avaliações

- The H.P. Lovecraft Drawing Book: Learn to draw strange scenes of otherworldly horrorNo EverandThe H.P. Lovecraft Drawing Book: Learn to draw strange scenes of otherworldly horrorAinda não há avaliações

- Absurdism in English LiteratureDocumento13 páginasAbsurdism in English LiteratureEmir100% (2)

- The Screaming Skull and Other Classic Horror StoriesNo EverandThe Screaming Skull and Other Classic Horror StoriesNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (8)

- 183 Good LadDocumento19 páginas183 Good LadYago GierliniAinda não há avaliações

- The Literary SchoolsDocumento26 páginasThe Literary SchoolsÂmâl AliAinda não há avaliações

- Construction Recruitment Company Profile V07102021 EmailDocumento14 páginasConstruction Recruitment Company Profile V07102021 EmailTakudzwaAinda não há avaliações

- 3 Day Challenge WorkbookDocumento29 páginas3 Day Challenge WorkbookMaja Bogicevic GavrilovicAinda não há avaliações

- Poem 3 Keeping QuietDocumento2 páginasPoem 3 Keeping QuietOjaswini SaravanakumarAinda não há avaliações

- Hafifah Dwi LestariDocumento9 páginasHafifah Dwi LestariHafifah dwi lestariAinda não há avaliações

- Lo3. Solving and AddressingDocumento8 páginasLo3. Solving and Addressingrobelyn veranoAinda não há avaliações

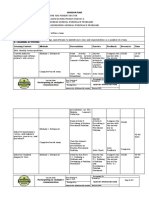

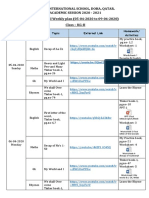

- Loyola International School, Doha, Qatar. Academic Session 2020 - 2021 Home-School Weekly Plan (05-04-2020 To 09-04-2020) Class - KG-IIDocumento3 páginasLoyola International School, Doha, Qatar. Academic Session 2020 - 2021 Home-School Weekly Plan (05-04-2020 To 09-04-2020) Class - KG-IIAvik KunduAinda não há avaliações

- Traditional IR vs. Web IRDocumento4 páginasTraditional IR vs. Web IRKaren Cecille Victoria-Natividad100% (2)

- 10 Benefits of ReadingDocumento4 páginas10 Benefits of Readingkanand_7Ainda não há avaliações

- Parts of Speech in FrenchDocumento3 páginasParts of Speech in FrenchApeuDerropAinda não há avaliações

- Anfis NoteDocumento15 páginasAnfis NoteNimoAinda não há avaliações

- MM5009 Strategic Decision Making and NegotiationDocumento11 páginasMM5009 Strategic Decision Making and NegotiationAnanda KurniawanAinda não há avaliações

- WLP - MIL Q1 Week6Documento2 páginasWLP - MIL Q1 Week6Clark DomingoAinda não há avaliações

- Unit 10 AssessmentDocumento54 páginasUnit 10 Assessmentstephen allan ambalaAinda não há avaliações

- Teaching Intercultural CommunicationDocumento24 páginasTeaching Intercultural CommunicationNashwa RashedAinda não há avaliações

- Order of Saturn - MSS CollectionDocumento19 páginasOrder of Saturn - MSS Collectionnoctulius_moongod6002Ainda não há avaliações

- SEA Program Oscar - Innerdance 2Documento4 páginasSEA Program Oscar - Innerdance 2Oscar CortesAinda não há avaliações

- User-Centered Approaches To Interaction Design: by Haiying Deng Yan ZhuDocumento38 páginasUser-Centered Approaches To Interaction Design: by Haiying Deng Yan ZhuJohn BoyAinda não há avaliações

- Conversion As A Productive Type of English Word BuildingDocumento4 páginasConversion As A Productive Type of English Word BuildingAnastasia GavrilovaAinda não há avaliações

- Hartapp Arc152 Midterm Exam Balbona DamianDocumento4 páginasHartapp Arc152 Midterm Exam Balbona Damiandenmar balbonaAinda não há avaliações

- Support Verb Constructions: University of NancyDocumento30 páginasSupport Verb Constructions: University of NancymanjuAinda não há avaliações

- Facilitating Learner Centered Teaching Module 19 26Documento72 páginasFacilitating Learner Centered Teaching Module 19 26Katherine Anne Munar-GuralAinda não há avaliações

- A. Report Iwcp2 (Melia Nova - 180107155)Documento63 páginasA. Report Iwcp2 (Melia Nova - 180107155)Baiq Imrokatul Hasanah UIN MataramAinda não há avaliações

- B1 UNITS 7 and 8 Study SkillsDocumento2 páginasB1 UNITS 7 and 8 Study SkillsKerenAinda não há avaliações

- SC Chap4 Fall 2016Documento43 páginasSC Chap4 Fall 2016Mohammed AliAinda não há avaliações

- The Importance of Value Education For Children NationDocumento6 páginasThe Importance of Value Education For Children NationInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyAinda não há avaliações

- Pedagogical PrinciplesDocumento3 páginasPedagogical PrinciplesAudrina Mary JamesAinda não há avaliações

- Space in Electroacoustic Music Composition Performance and Perception of Musical Space - Frank Ekeberg Henriksen - 2002Documento165 páginasSpace in Electroacoustic Music Composition Performance and Perception of Musical Space - Frank Ekeberg Henriksen - 2002Rfl Brnb GrcAinda não há avaliações

- Human-Centric Zero-Defect ManufacturingDocumento11 páginasHuman-Centric Zero-Defect ManufacturingAnanda BritoAinda não há avaliações

- Speech Recognition SeminarDocumento19 páginasSpeech Recognition Seminargoing12345Ainda não há avaliações

- LINUS 2.0 Screening SlidesDocumento28 páginasLINUS 2.0 Screening SlidesCik Pieces100% (1)