Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

Surface Anatomy of The Middle Division of The.15

Enviado por

bryan_millan_9Descrição original:

Título original

Direitos autorais

Formatos disponíveis

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Surface Anatomy of The Middle Division of The.15

Enviado por

bryan_millan_9Direitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

RECONSTRUCTIVE

Surface Anatomy of the Middle Division of the Facial Nerve: Zukers Point

Amir H. Dorafshar, M.B.Ch.B. Daniel E. Borsuk, M.D., M.B.A. Branko Bojovic, M.D. Emile N. Brown, M.D. Ralph T. Manktelow, M.D. Ronald M. Zuker, M.D. Eduardo DeJesus Rodriguez, D.D.S., M.D. Richard J. Redett, M.D.

Baltimore, Md.; and Toronto, Ontario, Canada

Background: The anatomy of the facial nerve and its branches has been well documented. The course of the extratemporal facial nerve, its anatomical planes, and the surface landmarks of the temporal division and marginal mandibular division are well known. However, the surface landmark of the middle division of the facial nerve has not been studied to date. Methods: Eighteen hemifacial dissections in 10 fresh human cadavers were performed through a preauricular face-lift incision. An 18-gauge needle with brilliant green dye was used to mark the nerve through the skin before dissection. The exact location of the middle division branches of the facial nerve was documented in relation to the transcutaneous marking. Results: The middle division branches of the facial nerve were found to lie at a mean of 2.3 mm from the tattooed point, with a range of 0 to 6 mm. A nerve branch was found directly tattooed by the needle seven of 18 times, inferior to the tattoo five of 18 times, and superior to the tattoo six of 18 times. Conclusions: The zygomatic/buccal motor branch that innervates the zygomaticus major muscle can be reliably found at the midway point on a line drawn from the root of the helix and the lateral commissure of the mouth. This study will help guide surgeons to the middle division of the facial nerve as it applies to facial surgery. (Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 131: 253, 2013.)

acial nerve anatomy has long interested plastic and reconstructive surgeons. Since the classic description of the surface anatomy of the frontal branch of the facial nerve and its pertinence to face-lift surgery by Pitanguy and Ramos,1 numerous authors have accurately described the extratemporal courses and planes of the upper, middle, and lower divisions of the nerve.27 The zygomatic/buccal branch that supplies the zygomaticus major muscle is critically responsible for smiling and is of specific interest to those who plan to use it as a donor motor branch for facial paralysis or facial transplantation operations. In this study, we performed 18 facial nerve dissections on 10 cadaver hemifaces to help elucidate the exact topical location of the zygomaticus major nerve branch as it exits the parotid gland in the midface.

From The Johns Hopkins Medical Institute; the R Adams Cowley Shock Trauma Center, University of Maryland School of Medicine; and The Hospital for Sick Children, University of Toronto. Received for publication July 23, 2012; accepted August 20, 2012. The first two authors contributed equally to the article. Copyright 2013 by the American Society of Plastic Surgeons DOI: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e3182778753

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Eighteen fresh cadaver hemifaces were dissected at the Anatomy Board of Maryland (Baltimore, Md.). A line was drawn from the root of the helix of the ear to the commissure of the mouth. The distance was measured and a transcutaneous tattoo with brilliant green dye was performed through the deep tissues with an 18-gauge needle (Figs. 1 and 2). The faces were dissected through a preauricular face-lift incision by the same surgical team. A subsuperficial musculoaponeurotic system dissection was carried anteriorly toward the nasolabial fold. When the transcutaneous tattoo was encountered on the anterior border of the parotid gland, the dissection was carried to the deeper plane. The parotid duct and middle division branches of the nerve were identified and dissected to their respective muscular targets (Fig. 3). A nerve branch supplying the zygomaticus major muscle was identified in all specimens. The distance of the nerve to the green mark was measured, as was its anatomical location in relation to the mark (Fig. 4). Disclosure: The authors have no financial interest to declare in relation to the content of this article.

www.PRSJournal.com

253

Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery February 2013

Fig. 1. Surface anatomy of a cadaver of Zukers point midway between the root of the helix and the commissure of the mouth. The green X indicates the location of the tattoo with brilliant green dye.

of 18 cases and superior in six of 18 cases. The mean distance from the root of the helix to the commissure was 107 mm, with an average tattoo distance of 53.33 mm from the root of the helix (range, 45 to 63 mm) (Table 1).

DISCUSSION

One of the senior coauthors (R.M.Z.) first noted the surface landmark of the nerve while performing facial nerve dissections in children with facial paralysis in the early 1990s. It became evident that the donor motor nerve branches that would be connected to the cross-face nerve grafts were reliably found at the midway point on a line drawn from the root of the helix to the commissure. This point, which served as a starting place for nerve mapping with nerve stimulation, has been consequently labeled Zukers point by one of the senior coauthors (R.J.R.) during his facial nerve dissections for facial nerve reanimation surgery. This clinical observation led us to examine the surface anatomy of the middle division of the facial nerve in a cadaveric study, and to confirm whether this point would be helpful in dissection of the facial nerve branches in preparation of a donor face vascularized composite allotransplantation. The senior authors (R.M.Z. and R.J.R.) have intraoperatively tattooed approximately 100 patients undergoing facial reanimation operations over the years. Routinely, this point is marked preoperatively and used as the starting point for mapping the zygomatic/buccal nerve branch of the facial nerve that stimulates the zygomaticus major muscle. This cadaveric study corroborates the clinical observation of the facial nerve by dem-

Fig. 2. Schematic drawing of the surface markings for identification of the middle division of the facial nerve. A point halfway on a line drawn from the root of the helix to the commissure of mouth is marked with an X. (Copyright Johns Hopkins University 2012, Department of Art as Applied to Medicine, The Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine.)

RESULTS

The middle division branches supplying the zygomaticus major muscle were identified as they coursed through and exited the parotid gland at a mean of 2.3 mm from the tattooed point (range, 0 to 6 mm). The tattoo actually perforated the nerve in seven of 18 cases (39 percent). The anatomical location of the nerve in relation to the tattoo was found to be inferior to the tattoo in five

254

Volume 131, Number 2 Anatomy of Facial Nerve Middle Division

Fig. 3. Preauricular incision of fresh cadaver. Dissection is carried to the nasolabial fold, exposing the underlying tattoo and facial branches.

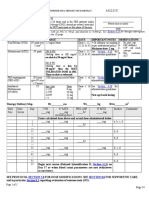

Table 1. Results

Distance of Tattoo from Root of Helix (mm) 50 51 51 60 59 63 63 55 47 46 45 50 48 50 58 58 53 53 53.33 45 63 Distance of Zygomaticus Major Nerve Branch from Tattoo (mm) 5 5 0.5 1 0 6 0 3 0 3 4 0 4 5 0 0 5 0 2.31 0 6 Location of Nerve Branch in Relation to Tattoo Superior Inferior Inferior Inferior On nerve Superior On nerve Superior On nerve Superior Superior On nerve Inferior Superior On nerve On nerve Inferior On nerve On nerve in 7 Superior to tattoo in 6 Inferior to tattoo in 5

Nerve Specimen 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 Mean Minimum Maximum

Fig. 4. (Above) A branch to the zygomaticus major muscle is directly tattooed with brilliant green dye. (Below) Green mark located just inferior to the buccal branch as it exits the parotid. Note the buccal branch as it inserts into the zygomaticus major. ZM, zygomaticus major muscle; PD, parotid duct; MD, middle division of facial nerve; M, masseter muscle; TT, transcutaneous tattoo of brilliant green at Zukers point.

onstrating that the branch of interest was found to lie at approximately 2.3 mm from Zukers point. This relationship is very useful in facial surgery for four reasons. First, the surface landmark on the skin may help limit the dissection area needed to find the appropriate donor nerve branch. This may potentially prevent damage to other branches of the facial nerve and reduce the amount of surgical tissue trauma in the area. Second, correctly identifying the location of the nerve preopera-

255

Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery February 2013

tively may help reduce the operative time needed to find the nerve. Less operative time in pediatric surgery and face transplantation surgery is of critical importance to patient safety. Third, this point provides a critical zone for surgeons who perform facial procedures, such as rhytidectomy, to help prevent nerve injury. To date, there are three commonly cited anatomical landmarks that are clinically used in facial surgery. The course of the frontal branch of the facial nerve as described by Pitanguy and Ramos,1 Dingman and Grabbs classic description of the marginal mandibular branch and its relation to the mandible and facial artery,8 and McKinney and Katranas detailing of the great auricular nerve and its relation to the ear lobule.9 Fourth, unlike the reference landmarks described by Pitanguy and Ramos and by McKinney and Katrana that use absolute distance measurements, such as 1.5 cm above the lateral brow or 6.5 cm below the caudal edge of the bony external auditory canal,1 Zukers point is related to fixed patient-specific anatomical markers that can be applied to adults and children irrespective of their size. Although the landmark is useful in guiding the surgeon to the appropriate branch, it is in no way a direct target to the desired nerve. Accuracy can be confirmed only with intraoperative nerve stimulation. In facial nerve reanimation surgery, for example, ideally the nerves should be mapped and two branches with the same function identified. This is of critical importance in some congenital bilateral facial paralysis cases where there is weakness on one side of the face, and when one might consider using the facial nerve as the power for a cross-face nerve graft. In this situation, a clear dissection of the distal components of the nerve is essential. If one sacrifices the nerve without identifying a second redundant nerve that has the same function, a patient may be left with a paralyzed donor side. Moreover, some branches that innervate muscles that are not pertinent to smiling may be found in the vicinity of Zukers point. This study does not identify the specific branch of the middle division that accurately recreates the patients particular smile because of the impossibility of nerve stimulation in cadavers. Nevertheless, the authors have successfully noted and correlated the finding clinically in adults and children alike (Fig. 5). The functional restoration of facial animation is essential in facial transplantation. Successful allotransplantation of the face depends on reestablishing healthy vascularized tissue that functions properly. This requires specific attention to detail in both the recipient and the donor dissections.

Fig. 5. (Above) Clinical demonstration of Zukers point. The green X is the location of the tattoo with brilliant green dye. The tattoo is made with an 18-gauge needle through the deep tissue. (Below) Clinical representation of the utility of Zukers point. The green tattoo is observed 2 mm inferior to the middle division of the facial nerve. Green arrow, transcutaneous tattoo of brilliant green dye at Zukers point; blue arrow, middle division of the facial nerve.

Facial transplantation groups have described different methods of facial nerve dissection, but all have stressed the importance of reinnervation of the facial musculature.10 12 In theory, nerves that are coapted closer to their respective muscular targets should have faster and more accurate recovery.12 There are a number of factors that are hypothetically necessary for successful facial nerve reanimation in facial vascularized composite allotransplantation. The recipients of face transplantation have heavily scarred facial tissues from the initial injury or from prior operations. Zukers point as a clinical landmark may be useful to guide surgeons to the general vicinity of the buccal and zygomatic branches of the facial nerve. Once these nerves have been identified, as in facial nerve re-

256

Volume 131, Number 2 Anatomy of Facial Nerve Middle Division

animation surgery, the distal nerve dissection can be completed to isolate the specific branches to the targeted facial mimetic musculature. At this point, the nerves can be tagged in anticipation of the donor nerves. In the donor, this clinical landmark could be beneficial to the surgeon in finding the middle division branches and would assist with speed of dissection and specificity of facial nerve anatomy. Targeting the branches directly would allow for less devascularization of the nerves and potentially hasten functional recovery. Correctly identifying and coapting the zygomatic and buccal branches in these patients is essential for establishing normal appearance and function.13,14 Moreover, Zukers point was mapped and accurately located the middle division of the facial nerve in both the recipient and the donor during the total face transplant performed at the University of Maryland Medical Center in March of 2012. Finally, the utility of this landmark is important to any surgeon who routinely performs facial surgery. Acquaintance with this critical zone may help surgeons avoid inadvertent dissection in proximity and ultimately potential damage to the facial nerve branches. This may be of practical utility in aesthetic procedures, such as rhytidectomy, where inadvertent nerve injury is consequential. The shortcoming of this investigation is inherent in the fact that it was a cadaveric study. The relationships of the nerve branches to the surface landmarks may be distorted in the specimens, and functional nerve stimulation is not possible. Notwithstanding this limitation, given the clinical experience of the senior authors (R.M.Z. and R.J.R.) in using this landmark, combined with the findings of this study, we can conclude that Zukers point is a valuable surface anatomical mark for the middle division of the facial nerve. of the facial nerve to predictably lie below Zukers point halfway between the root of the helix and the lip commissure. This surface marker serves as a useful clinical guide for facial nerve surgery.

Amir H. Dorafshar, M.B.Ch.B. The Johns Hopkins Medical Institute 601 North Caroline Street Baltimore, Md. 21231 adorafs1@jhmi.edu

REFERENCES

1. Pitanguy I, Ramos AS. The frontal branch of the facial nerve: The importance of its variations in face lifting. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1966;38:352356. 2. Ziarah HA, Atkinson ME. The surgical anatomy of the mandibular distribution of the facial nerve. Br J Oral Surg. 1981; 19:159170. 3. Bernstein L, Nelson RH. Surgical anatomy of the extraparotid distribution of the facial nerve. Arch Otolaryngol. 1984; 110:177183. 4. Laing MR, McKerrow WS. Intraparotid anatomy of the facial nerve and retromandibular vein. Br J Surg. 1988;75:310312. 5. Stuzin JM, Wagstrom L, Kawamoto HK, Wolfe SA. Anatomy of the frontal branch of the facial nerve: The significance of the temporal fat pad. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1989;83:265271. 6. Gosain AK. Surgical anatomy of the facial nerve. Clin Plast Surg. 1995;22:241251. 7. Chowdhry S, Yoder EM, Cooperman RD, Yoder VR, Wilhelmi BJ. Locating the cervical motor branch of the facial nerve: Anatomy and clinical application. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2010; 126:875879. 8. Dingman RO, Grabb WC. Surgical anatomy of the mandibular ramus of the facial nerve based on the dissection of 100 facial halves. Plast Reconstr Surg Transplant Bull. 1962;29:266 272. 9. McKinney P, Katrana DJ. Prevention of injury to the great auricular nerve during rhytidectomy. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1980;66:675679. 10. Alam DS, Papay F, Djohan R, et al. The technical and anatomical aspects of the Worlds first near-total human face and maxilla transplant. Arch Facial Plast Surg. 2009;11:369377. 11. Meningaud JP, Hivelin M, Benjoar MD, Toure G, Hermeziu O, Lantieri L. The procurement of allotransplants for ballistic trauma: A preclinical study and a report of two clinical cases. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2011;127:18921900. 12. Singhal D, Pribaz JJ, Pomahac B. The Brigham and Womens Hospital face transplant program: A look back. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2012;129:81e88e. 13. Pomahac B, Lengele B, Ridgway EB, et al. Vascular considerations in composite midfacial allotransplantation. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2010;125:517522. 14. Meningaud JP, Paraskevas A, Ingallina F, Bouhana E, Lantieri L. Face transplant graft procurement: A preclinical and clinical study. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2008;122:13831389.

CONCLUSIONS

Although surgeons have acknowledged the surface anatomy of the upper and lower divisions of the facial nerve, the location of the middle division and its relationship to the overlying skin have not been established. This cadaver study confirms the location of the middle division branches

257

Você também pode gostar

- Maxillofacial Trauma MedellinDocumento8 páginasMaxillofacial Trauma Medellinbryan_millan_9Ainda não há avaliações

- Wound Closure ManualDocumento127 páginasWound Closure ManualDougyStoffell100% (5)

- Emergency Treatment of Facial Lacerations of Dog Bite WoundsDocumento5 páginasEmergency Treatment of Facial Lacerations of Dog Bite Woundsbryan_millan_9Ainda não há avaliações

- CDC February 2014Documento179 páginasCDC February 2014bryan_millan_9100% (1)

- 10 Bad Listening HabitsDocumento5 páginas10 Bad Listening HabitsAlfadilAinda não há avaliações

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeNo EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (5794)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingNo EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (399)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryNo EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (231)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceNo EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (894)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)No EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Nota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (98)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureNo EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (474)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItNo EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (838)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaNo EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (265)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerNo EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (271)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersNo EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (344)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnNo EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (234)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaNo EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (45)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyNo EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (2219)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreNo EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)No EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Nota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (119)

- Bowel ObstructionDocumento48 páginasBowel ObstructionPatrick John100% (1)

- Forensic ToxicologyDocumento7 páginasForensic ToxicologyLaiba Jahangir100% (2)

- NstiDocumento12 páginasNstiKania IradatyaAinda não há avaliações

- India Immunization Chart 2010Documento1 páginaIndia Immunization Chart 2010Sarath Nageshwaran SujathaAinda não há avaliações

- 12 SP Physical Edu CbseDocumento9 páginas12 SP Physical Edu CbseshivamAinda não há avaliações

- Mechanisms, Causes, and Evaluation of Orthostatic Hypotension - UpToDateDocumento20 páginasMechanisms, Causes, and Evaluation of Orthostatic Hypotension - UpToDateCipriano Di MauroAinda não há avaliações

- Adenosine Life MedicalDocumento20 páginasAdenosine Life MedicalLaura ZahariaAinda não há avaliações

- BPH PSPD 2012Documento43 páginasBPH PSPD 2012Nor AinaAinda não há avaliações

- Addiction CaseDocumento4 páginasAddiction CasePooja VarmaAinda não há avaliações

- Reaksi Hipersensitivitas Atau Alergi: RiwayatiDocumento7 páginasReaksi Hipersensitivitas Atau Alergi: Riwayatiaulia nissaAinda não há avaliações

- Jazel Ibon Galon PDFDocumento2 páginasJazel Ibon Galon PDFJazel GalonAinda não há avaliações

- Ace InhibitorsDocumento26 páginasAce InhibitorsDeipa KunwarAinda não há avaliações

- 2023 ACC Expert Consensus Decision Pathway On Comprehensive Multidisciplinary Care For The Patient With Cardiac AmyloidosisDocumento51 páginas2023 ACC Expert Consensus Decision Pathway On Comprehensive Multidisciplinary Care For The Patient With Cardiac AmyloidosisERIK EDUARDO BRICEÑO GÓMEZAinda não há avaliações

- TMG Versus DMGDocumento3 páginasTMG Versus DMGKevin-QAinda não há avaliações

- Simplicity and Versatility: Philips Respironics Trilogy 202 Portable Ventilator SpecificationsDocumento4 páginasSimplicity and Versatility: Philips Respironics Trilogy 202 Portable Ventilator SpecificationsVincent Seow Youk EngAinda não há avaliações

- Ayurved TerminologiesDocumento30 páginasAyurved TerminologiesVipul RaichuraAinda não há avaliações

- High Risk B-Precursor Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia Interim Maintenance IIDocumento1 páginaHigh Risk B-Precursor Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia Interim Maintenance IIRitush MadanAinda não há avaliações

- Chapter 4 A1 Poster Example 2Documento3 páginasChapter 4 A1 Poster Example 2Krisna PamungkasAinda não há avaliações

- Cam4 5 1239Documento12 páginasCam4 5 1239kadiksuhAinda não há avaliações

- UNAIDS Core Epidemiology Slides enDocumento11 páginasUNAIDS Core Epidemiology Slides enTabarcea VitaliAinda não há avaliações

- Daftar Obat Klinik MPHDocumento3 páginasDaftar Obat Klinik MPHxballzAinda não há avaliações

- Onnetsutherapys 130128035904 Phpapp01 PDFDocumento70 páginasOnnetsutherapys 130128035904 Phpapp01 PDFjavi_reyes_17Ainda não há avaliações

- Drug Tabulation orDocumento23 páginasDrug Tabulation orChin Villanueva UlamAinda não há avaliações

- The Sage Encyclopedia of Abnormal and Clinical Psychology - I36172Documento5 páginasThe Sage Encyclopedia of Abnormal and Clinical Psychology - I36172Rol AnimeAinda não há avaliações

- Secretin Hormone Activates Satiation by Triggering Brown FatDocumento1 páginaSecretin Hormone Activates Satiation by Triggering Brown FatTalal ZariAinda não há avaliações

- Hip DislocationDocumento4 páginasHip DislocationcrunkestAinda não há avaliações

- Integrated Management of Childhood Illnes1Documento5 páginasIntegrated Management of Childhood Illnes1Ryan VocalanAinda não há avaliações

- Antimicrobial Mouthwash - Google SearchDocumento1 páginaAntimicrobial Mouthwash - Google Searchbruce kAinda não há avaliações

- AbijitDocumento3 páginasAbijitvimalAinda não há avaliações

- Platelet Rich FibrinDocumento7 páginasPlatelet Rich FibrinNelly AndriescuAinda não há avaliações