Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

Basa - Relationship Between SE Asian and Indian Glass

Enviado por

Charlie HigginsTítulo original

Direitos autorais

Formatos disponíveis

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Basa - Relationship Between SE Asian and Indian Glass

Enviado por

Charlie HigginsDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN SOUTHEAST ASIAN iNDIAN GLASS

Ian

INTRDDUCHON

In of beads Southeast (1965a:89) that

"It is rather ... that in the literature of Southeast Asian archaeology so little

attention ha:!! been paid to beads". More than two decades later the scene was not much

different. In the SPAFA Seminar on Prehistory of Southeast Asia, 12-25th January

it W@:l that

!!lost parts oif "''-""H''"'"''" Asia, of glass stone

the earliest of contact with East, South and Southwest Asia. And yet thus far

we know relatively little about their dating, manufacture, possible sources, nor of

the trade systems that brought them together 1987: 335) ..

comprehen:;ive of "'"'"'m""'uu1._, ......

from AsiaCJ In this trade between India and

from about 400 BC to about AD 500 wiH be discussed with attention to

morphological analytical studies of glass beads. In the discussion, the evidence

Ban Don Ta Phet is particularly important, because the numet:ous beads from

site dated and have contexts and the materia( associated

with at burial; archaeology Southeast Asia.

EARLY GLASS IN SOUTHEAST ASIA

There is no evidence of beads in Southeast Asia before the Iron Age, that is

before 600-400 BC. In Vietnam the earliest is dated to the 4th-3rd century BC

Ki Thailand 400 BC

beads an

radiocarbon dates mnging from the 5th century BC to the 2nd

1979:212-3). for only sites (Gilimanuk

and Pasir

Bail

Indo-Pacific Prehiswry Assn. Bulletin 1991:366-385 (P.

Anthropology, Utkal University, Bhubaneswar 751004, India

Institute of Archaeology, 31-34 Gordon Square, London OPY, United .Kingdom

of the

Research Lab. for Archaeology and the History of Art, 6 Kebie Road, Oxford OXI 3QJ, United Kingdom

10

26 ('\,

it

arl

lass

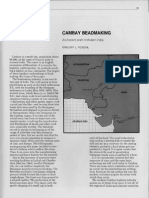

1 Non Ki Klang, 2 Sa

3 Ban Chiang, 4 Ban Na Di

5 Non Chai, 6 Phu Kibao

Pa

17 Vichayen' s House

18

21 Ban Don Ta l'het

22 Prasat Muang Singh

Pra Pathom, 24 Khok

25 Ku Bua, 26 Kok Ra Ka

27 Khao Sam Kaeo, Wat

29Laem 30 Ko Kho Khao

31 KantNam

32 Khlong Thorn

33 Nakom Si Thammarat

34 ........ ,,.

FIGURE 1: SITES !IN THAILAND WITII FINDS OF GiLASS

368 BASA, I. GLOVER AND J. HENDERSON

GLASS BEADS FROMBANDONTAPHET

The site of Ban Don Ta Phet lies on the southern

name in Kanchanaburi of West Central Thailand

over three seasons, first the Fine Arts

under Chin You-Di in and

of London and the FAD

basis of five consistent radiocarbon dates made on

of the

It was

in five rather earlier than once such a date is

not inconsistent with the age of similar etched carnelian and beads and

historic India. The site is in the context of this paper because it has

best corpus and widest range of beads of any site in Thailand

and indeed in the whole of Southeast Asia. A few and

distinctive ear ornaments were also found.

Shapes Transhu::ent beads Opaque beads

Colourless Honey Green Blue Violet 'Black' Orange Red Dark Grey Total

Spherical-elliptical 9 3 51 170 2 9 1 285

Barrel 54 1 452 135 2 3 509 3 11 59

Annular 28 8 9 2 312 446

Cylindrical 1 51 67 3 222 443

Cornerless cube 2 1 8

Bipyramidal/biconical 54 5 HI 20 137

Square prism 2 3 25 3 1

Hexagonal prism 3 26 55 84

9 9

4 51 38 37 4 77 2 1 1

Total 154 1 3 1 799 516 7 3 4 1116 83 2813

TABLE 1: GLASS BEADS FROM BAN DON TA PHET FROM ALL SEASONS, BY PlllNCIP AL

COLOURS AND SHAPES2

~ .. ~ ~ ..... all the glass beads from Don Ta Phet are monochrome, there is a wide range

of colours and tones which can be broadly grouped 1) into translucent and opaque

The former include colourless, honey, green, blue, grey-black and orange;

the latter include red (both opaque browny red and opaque orange red) and a few dark

grey specimens. The opaque red and opaque orange beads are of the often

known as , an Indonesian term used by Rouffaer (1899) in his

of beads among the communities of Timor and Flores who them as

of great value. Mutisalah beads constitute about forty percent of the glass bead collection

at Ban Don Ta about the same proportion as in the collections from Kuala Selinsing

BC to lOth AD) and Pengkalan centuries m

Peninsular Malaysia (Lamb 1965a:96). Many of the mutisalah beads show striations

to the hole and flat ends indicating that were drawn and cut from a

EARLY SOUTIIEAST ASIAN AND INDIAN GLASS 369

52 3 6

830

I

{J

53 4 1

4248

6075

2cm

6242

6028

3839

2cm

FIGURE 2: SMALL AND MAINLY NON-PRISMATIC GLASS BEADS FROM BAN DON TA PHET

5236 barrel; 5341 tabular diamond; 830 spherical; 4248 elliptical; 6075 and 6028

annular; 6242 cylindrical; 3839 biconical; lower right is segmented.

98

1 4 7 1

;;; 2cm

FIGURE 3: LARGER AND PRISMATIC BEAliJI FROM BAN DON

3175 and square 4427long 929 and 3155 prisms;

cornerless cube; 1272 bipyramidal

one fmm trapped in the

Xl;JIO!Iea when dra\W tubes were cut These are

manufacture 1990:8-15). MU4i!!alah belong

of "Indo-Pacific Mons:x:hrome Dr>RwrJ Glass Bead" identified by Francis

(1990:2)" 13-5) mentions t!tJ.at a number of the beadrc

Phet have cubic, bipyramidai, 1ilquare prismatic shapes

and imitate the forms of natcual mineral famous

'-LV<>1A"'" of South India. Prism.atic noted only rarely in

Asia, for instance at ]3\an (Malleret 1962:250).

diamond shaped tabular glass bead

polished no. 5341) and resembRes a

Phet and elsewhere ire Southeast

SalebabP (Benwood 1985:309,

FIGURE 4: UNIQUE COlriMASIIAPED mANSLUCENT U;HTLY TINTED GLASS EARRING FROM

liMN DON TA PHET, 19754 SEASON

(max. diam. about 5 em)

GLOVER HENDERSON

Sorr.,c of the bracelets too, Glover 1990a do not resemble ones known from

c:ontemporaxy sites.

EARLY GIASS IN 'IRE TRADE OF GLASS FROM INDI.A TO SOUTHEAST ASJA

have suL'!Im<uised the

trade between and Asia. The traded

(especially the etched varieties), high-tin bronze

regional

in trade. For

Kumrahar and Chandrak.etugarh

a::dve in

evidence to show

continued on,

and no

silk doth and silk yz.rn, well

vessels survive in som.e archaeological

Monochrcr:>e beads of differs=:m: cdours

However, Ar-ikamedu (Wheeler et

BC and early centuries

matm.Jifalctu.!in:?I. centres of the nmnochrome

varieties (Francis 1982.a, 1982b, Stem 1987). In Thailand

many Late Prehistoric sites such as Ban Chiang, Ban Na Di, Non Ban Tha

Ban Don Ta Prasat Muang and Kok Ra Ka (Basa n.d.). have also been

found at Kampong Lang centuries BC the early centuries: AD) in

Peninsular Malaysia, Sembiran in Bali (late centuries BC to the centuries

AD; and Bell'l:vood 1991 ).

The earliest evidence for manufacturing glass beads in Thailand comes from Khlong

Thorn, dated to about the 4th century AD onwards (Bronson 1990; but remember our

comment above on the presence of some locally shaped glass at Don Ta In

EARLY INDIAN GLASS 373

Peninsular Malaysia the beads comes from

Selinsing, recently dated between 200 BC and 1000 (Shuhaimi 1991).

the glass-bead-yielding levels In Gilimanuk, a

'Christian Era, is clz,imed to be

although Fnmcis

claims that glass beads

beads of trJ.nslucent d<:.rk blue Ta Phet.

One such blue bead has biC>en ~ " ' w ' " ' " ' ' " ' " burial near Tegurvvangi

Sumatra (Hoop from Taxila from Bhir

1941:27) and about the beginning the ' " ' ' ' " " ' " " ~ " " ' " "

Era to AD (Ghosh 21 ). This shape is common

(Beck and r:c a.y be

import from there.

Ban Ta 349 translucent beads

rarely reported in Southeast Asia; a few k11own as surface or uncontext:ed

finds from Ban Chiang and Oc Eo and one or two come from the :::tone cist graves at

South Sumatra (Hoop Many of these an: form of hexagonal

u ' ' " ~ ~ , ~ u barrels, square prisms and square barrels out earlier,

mimic the beryl crystals of South India which popular in the Buddhist

North India as the Roman world. These

who mentioned imitations were made in

tt.ND J. HEN1JERSON

f'uikamedu

no.

r;f GraecoRomafl

of this - o?Ie from the surface

Glass beads of similar

their

glass besds were rnanufactured

are :>:.urprisingly rare South Asian

recorded few such in surface

the last being dated

bead was also

1948:75, Plate

CHEl\HCA.L PREHISTORIC sm.riJ:-IE.""ST ASIAN GLASS

ma.ny was c.\11 %. TI1e

'JClriOSCIJpe wfih a Link

In Tabies 4 ami 5 a dash or a

sources consulted.

determined4;

Samples

were

2-5 the

Electron

a 4

that the

ll:.ly their find numbers) were

arc:nc;.'"'mo;D.C3:J COJ1telrts dating to the 4th century BC Those Sembiran (S2-6) were

also archaeological :cmtexts and probably AD 1 and 200 (Ardika

ami Bellwood 1991). 'Ihe Ban Chiang (BCl) was a surface find. Colours

are by thus TCG means means

t.ranslucent dark TCW means translucent of the colourless

heads have intemai cracks which appear whitish due light reflecting off internal

OER means opaque TP means translucent purplish and TOG

meam: translucent olive green, The red colour is different frmn a much brighter

se1l!H:!!l',''llruC red found ancient technology; borne out in the

EARL Y'SOUTHEAST ASIAN AND INDIAN' GL.<\SS 375

:.nd chemical of the two kinds red. On

3957

6114

some

IS

(Hass

Bead type NrJ20

OBRtbarrel 10.4

11.1

11.8

11

08R!ob!atc 12.0

OBR/cyHnoer 6.1

1.1

1.4

1.5

1.7

beads can be grouped into tc:'o bread

Sodium predomimltes in the an'i

SPJ2 K20

;8.6 5. i

S3.7 0.6 0.3 4.2

5.:) 66.9 0. 7 0.3 4, 7

'i C-\

6.7 62.9 0.6 0.3 :1A 2.6

6.2 GG.O

60.9 4.7

used seep. 374.

Tiij2

0.5

0.4

0.5

0.5

0.2

nd (K

2

0)

Fe2U:l Cu20 Total

2.3 2.5 101.6

2.0 93.6

2.2 2.4 99.1

:'.::1 colour

e!it!t!l

15.5

1 5.3

te.s .. ;c

1 0.30

2./ 2.5 101.4 16.9

2.0 10.8

though

in

m:v;eathered s,mples. 5234,

brovvn bead from B::an Don Tc:

level above 0.8% would

from Ban

1.0%

the final colon;: acbjeved would on a range other factors (Green and

Hart oxide is in bead2 from Ban Don Ta Phet, ranging up

2;emd No. [\]:0120 Ai203 I'205 S@2 C! K20 Cv:! Ti02 MnO Fe203 CQ.;_t:J Totm! '%,Jots! JlKall K201N211

1293

1432

7171

8010

9142

82

S3

S6

BC1

()_2 0.6 72.g G.4 Nil Nil 16.6 5.7 NO Nil 0.3 g)_4 88.0

0.4 0.2 74 9 :-n 0.1 IIIJ 15.6 I'll) NO 0.2

TCG!hex.prism 0.7 0.6 G 2 74.5 NO NO 4.9 NO

TO<::' fragment 1.3 1.3 2.2 69.6 0.4 17'.4 3.9 NO LD

l"2G/elliptical 0.5 NO L5 NO 02 15.0 L2 NO

TDGiob!ate ND 0.5 0.0 73.0 1\1) I 7.3 3.2. NO 1.0

TBGJbarre! 3.C iLS 0.1 NO 2.4 0.1

TOWbarrel 1.4 0.5 1.9 G\:.5 NO 0.3 3.1 0.1

TBdraqment 0.2 0.2 C.B 68.1 NO 0.7 0.5 1 1.5 NO NO

TBifr-v H91Ct 0.5 0. 77. i 0.6 h-!D 0.1 18.2 3. 7 ND NO

1.4 (l.4 1 70.3 NO I'D 18.2 ND NO 0.6

ND 0.2 :J.9 74.3 NO ND 16.5 3.8 NO N;)

-::.2 0.6 0.6 i\0 ND 16.6 ND NO 0.2

1.3 6S.0 ::.6 0.3 ND 'j 2.8 0.1 0.3 2.0

TDB/bcwrai 0.4 2.8 7!. { NO 0.4 NO 15.6 0.3 1.9 1.2

W 1.0 74.1 0 3 0.3 I 6.3 1.1 NO 1.0

o.a 1. ::.:.6 70.1 1.0 0.1 17.3 3.0 NO 0.'

'i.2 NO 37 75.5 NO 'i 3.4 0.4 0.5

!?(J;'fASSl1 .M-RI<::Zf FRC:MBANDON SEMBI RAN

OX!JlJES;.

the

g::.cup th.ere is no

and colour since S(rtl.:c: translucent

U 2.4%. This can

and in i_s, oxidised

is present

1

n a

agent :;rhich would help

and in these glasses

96.2 1!5.6

0.1 97.5 16.9

1.8 99.7 18.7

2.4 93.8 5.5

O.S 9-5.1 17.3

1.6 98.9 18.2

1.1 94.3 17.0

NO 98.4 17.6

NO 18.2

19.6

NO 95.8 16.5

100.6 16.8

1

1 Oi.S

ND 98.8 \7.7

2.5 100.3 18.7

l!LS

CHIANG

is consistent

to precipitate out

to those

eentury AD and (Henderson

used i: : corn positions are :)is tinct in other

n.vo mutisalah beads in the potassium and S6

ontain 2.5-3.1% copper present oxide

TI'ilE COMPOSffiON SOUT.dEAST ASIAN GLASS AND ITS SOURCES

Brill (1987:4) mentions that mixed-alkali rather rare the but recently

n.o

23. i

13J'

30.0

87.0

3.8

11.1

87.0

91.0

1:"LO

82. c

C:3.0

\1.0

1.!;

1.c

1.2

been from Broeze contexts of 11th-7th centuries BC in northern Italy,

Switzerland and implying the of European source for this earlier

1988:84). to Hendenmn 81, 89), there were three main

corn positional types silicate glass in before the 2nd AD. They 'were:

EARLY SOUTHEt\ST AS!AN AA"'D INDIAN GLASS

S03 14:20 c.o

%Total

0.1 4.3 4.8 0.3 1.2 0.7 L3 100.1

75.9 0.2 3.9 1.8 0.2 2.6 1.5 100.0

64.5 3.9 5.0 0.3 0.2 LS 1.9 98.0 17.4

4.5 66.7 4.0 4.6 0.3 0.1 1.3 2. j iOO.O 18.3

61.2 4.6 0.2 0.0 0.2 100.1 19.6

6 .. 9 63.2 7.4 4.8 0.2 0.1 2.6 3.9 99.9 16.1

4.7 57.3 6.9 3.3 0.4 4.5 10.9 100.0 14A

5. 7 61.2 6.4 5.2 0.4 0.1 1.5 0.1 100.0 22.2

Sar Dheri 3.5 3.9 61.7 7.2 5.2 0.3 0.1 1.3 0.2 100.0 23.5

Sar Dheri 5.0 2.3 59.6 7.2 5.0 0.1 0.1 1.2 2.0 99.8 24.2

Sar Dheri 3.2 4.2 61.7 7.5 6.4 0.3 0.1 1.2 0.1 100.0 22.6

S<>r 4.5 60.0 6.3 6.4 0.2 0.4 1.5 0.1 100.1 23.0

4.0 5.7 5EL "l 4.8 8.9 0.2 1.7 100.2 21 .6

TaxHa 0.5 2.9 4.9 7.1 0.0 99.7 17.7

0.1

16.1 tr 3.1

72.9 11.4 2.4 0.9 3.7

76.3 14.4 2.0 0.8

76.9 12.9 1.8 0 2 0.8

2.1 74.0 16.1 1.2 0.2 L5 2.2

80.4 HL7 3.9 2.6 0.1

0.7 0.9 2.5 76.4 14.1 2.0 0.1 1.5 1.4

Hulaskhera 0.1 16.9 3.6 0.3

Udayagiri 4.1 2.0 3.4 59.6 19.0 7.6

TABLE S. POTASSIUM-.RICH GLASS IN SOUTH ASIA (Wf, % AS OXIDES),

vv"'"'"""' < 1% are not not listed.

codes used seep. 374.

is unusual

9th-7th centuries BC

have been found in earlier Bronze

alkali

0.29

0.92

0.42

~ . 3 8

south from Sar Dheri and Kausambi in north India and TaxHa in Pakistan

:178 K. I. GLO"\'ER AND '-!ENDERSON

Tc

X

X

POTASH

GLASSES

X

Te

.,

To

xlSc x

X

X

X

u

= Mixed-alkali glass from

Do'' Phct Scmbirnll

X = Po!aSll glass

Ban Doo Ta Phct, Sembimn,

Ban {.:;c,i;mg

EARLY SOUTHEAST ASIAN AND INDIAN GLASS 379

mixed,alkali glasses from BDTP and Sembinm group

Kausambl and Sar glass. the same analytical

Fn::m the rJcq,c of

liable be the most technically difficult to manufacture.

is very rare in the Middle E<lst and

du'""''"'"'"' chf:mi::al Roman colourless

translucent blue from Stradonice, Bohemia of the 1st-4th cemuries

indicate that the Roman containea 12-14%

levels

in additioa

Hulashkera and Hastinapura in northern India (Table

from China to Ban Don Ta Phet in the 4th BC seems !;inc:e the forms of

Thai resemble oflndic there other e.vidence of 'Al'""'"''"'

material on the site.

Lal (1987:54) mentioned that some of the glass beads from Arikamedu have a four

the in

into this, category,

contents.

An apparently "black" glass bead from Ban Don Ta Phet (5653) has a high iron oxide

c;ontent This green when examined transmitted light

is reduced it can with on!;; Arikamedu

(Di.kshit 1969:151 ).

The Sembiran most from south India, from

most fm Indo"Pacif:ic glass be;J\d.s

which made both mixed-alkali and potassium glass. The recovery of the Rouletted ware

at Sembiran (Ardika and Bellwood 1991) strengthens the link bei"Neen Arikamedu and

Bali. it does not follow that Edi the heads

in Southeas:t Asia were imported from P.rikamedu. <LA::rm:po:sttlonal

380 K. BASA, I. GLOVER AND J. HENDERSON

studies show that certain types of typical north Indian glass beads are also found in

Southeast Asia and it is fair to assume that more than one centre in India exported them.

RELATIONSHIPS BETWEEN INDIA AND SOUTHEAST ASIA

During the period under study (400 BC-AD 500), India witnessed the emergence of

mature states - the Mauryas, Kushanas and the Guptas in north India and the

Satavabanas in the Deccan. During that period, south India had some powerful

chiefdoms such as the Cberas, Cholas and the Pandyas, some of which emerged as

urbanised states like that of the Pallavas who ruled over Tamilnadu during the 4th-6th

centuries AD. Despite the political plurality, what mattered for trade was the

diversification of arts and crafts under some form of guild (srenz) system, and the issue of

a wide range of coins by cities (nigama) and tribes (gana) in different areas. Trade based

on profit is well descnbed in the Arthasastra. An elaborate bureaucracy developed,

especially in the Mauryan state, and there was a considerable development of both

overland and maritime trade routes. There were regional variations in organization of

trade as Ray (this volume) makes clear. For example, in the north-western part of the

Indian sub-continent, trade was controlled by a sahaya association. In Tamilnadu, the

paratvar comprised inhabitants of the coastal tract who bad diversified from their

traditional occupation of salt making and fiShing into long distance trade. Moreover, the

term nikama, meaning nigama or exchange centre, is mentioned in the Tamil Brahmi

imcriptions from the Madurai region on the river Vaigai. Inscriptions from Mathura and

the Deccan also refer to the organization of guilds by traders in specified commodities.

Guilds also acted as banks and places for investment.

Politically, India's interest in Southeast Asia was commercial and not imperialist or

interventionist. The only evidence of the latter is the invasion by the Chola kingdom of

south India of the Srivijaya kingdom in Sumatra in the 11th century AD. In Southeast

Asia at this time the highest levels of political organisation were chiefly societies and at

best some nascent states. Barter is likely to have been the only mode of exchange.

Wisseman Christie (n.d.) bas argued for the emergence of three clusters of producer-

trading states in Peninsular Malaysia during ~ h e late centuries BC; in the Perak-Bemam

river valleys, in the lower courses of the Kelang and Langat rivers, and in the upper

Pabang-Tembeling river valley in the mountainous interior. Nevertheless, the first issues

of coinage in Southeast Asia, the so-called "Pyu coins", do not seem to predate the 7th or

8th centuries AD (Cnbb 1981) and seem to have bad a restricted circulation in the major

river basins of modem Burma, Thailand, Cambodia and southern Vietnam.

With a lack of written records we ~ a n n a t analyse, in the same detail as is possible for

India, the structure of exchange within Southeast Asia for the thousand years from the 5th

century BC. Good archaeological documentation is still scarce and we depend on models

based on analogies from more recent historical and ethnographic situations. For instance,

Bronson (1977), Wheatley (1975), Wolters (1982), Miksic (1984) and Wisseman Christie

(1982 and n.d.) have all proposed evolutionary or structural models for Southeast Asian

exchange systems. Although useful, these are generalised and abstract and, for the most

EARL YSOUTI-IEAST ASIAN AND INDIAN GlASS 381

part, lack firm support from empirical data from the past. Elsewhere, Basa (1991) has

explored in some detail the implications of these models, and also a modified "World

Systems" approach, for achieving a higher-level understanding of the role of the glass

bead trade in the development of social elites in Southeast Asia.

In this brief report we can sum up the position by emphasising that the westerly trade

of Southeast Asia during the period from about 400 BC to AD 500 was not a mere "trickle

of trade", nor can it be described simply as the "drift" of a few exotic and precious items to

the east from India. Rather it operated on a considerable scale at pan-regional, regional,

and local levels; it was developed as a commercial enterprise by Indian merchants; and

there is little doubt that Southeast Asian sailors and traders were also active in the

exchanges. The trade stimulated the growth of chiefly societies in Southeast Asia and

prepared the ground for the transformation to state-level organisations in the mid first

millennium of the Christian Era.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

In the study and analysis of glass beads, Basa received considerable help from Dafydd

Griffiths of the Institute of Archaeology and from Gerry McDonnell and Mike Heyworth

of English Heritage. I Wayan Ardika and ~ t e r Bellwood provided samples of glass beads

from Sembiran for comparative analysis. We thank all of them. However, we are

responsible for the interpretations put forward here.

F001NOTES

1 The Pasir Angin dates are 1050160 bp (ANU 1110), 1280170 bp (ANU 1112), 43701190 bp

(ANU 1109) and 2460440 bp (ANU 1113).

2 Table 1 shows the glass beads from all the three excavation seasons at Ban Don Ta Phet. It has

been compiled from Figures 5.8-5.10 in Basa (1991) where more typological distinctions are

indicated and the totals for the three seasons are separated.

3 This ornament was described as "crystal" when published by Chin You-di (1978: Colour Plate 5),

but is described as "glass" in a fine postcard of the piece on sale at the National Museum, Bangkok.

Mr Somchai Na Nakorn Phanom and Dr Warangkhana Rajpitak of the National Museum recently

examined the piece for us and confirm that it is indeed made of glass (pers. comm. 29.3.1991).

4 The analyses of glass from Don Ta Phet, Sembiran and Ban Chiang were done at the Ancient

Monuments Laboratory of English Heritage. Analyses of glass from other sites in Southeast Asia

have been published by van der Hoop 1932:170; van Heekeren 1958:41; Malleret 1962:465-9;

Harrisson 1963:237, 1964:38, 1968:129-31; Lamb 1965a:100-8, 1965b:36, 1966:86-7; Lugay

1974:161-2; Indraningsih 1985:139; and McKinnon and Bri111987:9-12. Results of further analyses

on beads from Don Ta Phet are awaited, and when these are available a more ambitious statistical

analysis of Asian glass will be made. [Tables 2 to 5 have been printed as received from the authors;

subscript chemical numbers would have necessitated retyping- Ed.]

382 K. BASA, I. GLOVER AND J. HENDERSON

5 Table 4 is based on analyses published by Dikshit 1969:151; Lamb 1966: 87; and Brilll987:17.

More analyses of South Asian glass have been published by Sen and Chaudhuri 1985.

6 Table 5 is based on analyses published by Dikshit 1969:150; Lal1952a:25 and 1952b:56; Agrawal

et al. 1987:60; Brill 1987: 18-20; and in the Annual Report of the Archaeological Survey of India for

1922-23, p.l58.

REFERENCES

Agrawal, 0. P, Jain, K. K. and Singh, T. 1987. Analysis of glass from Hulaskhera. In Bhardwaj,

H. C. (ed.) 1987a, pp. 57-62.

An, Jiayao n.d. Ancient glass in southeast coast of China. Paper presented in International Seminar

on Ancient Trade and Cultural Contacts in Southeast Asia, 21st-22nd January 1991,

Bangkok.

Ardika, I. Wayan and P. 1991. Sembiran: the beginnings of Indian contact with Bali.

Antiquity 65:221-32.

Basa, K. K. 1991. The Westero/ Thuie of Southeast Asia from c.400 BC to c.AD 500 with Special

Reference to Glass Beads. Ph. D. Thesis, University of London.

- n.d. Early glass beads in Thailand. To be published in M. Santoni (ed.), Southeast Asian

Archaeology 1988.

Beck, H. C. 1941. Beads from TariJa. New Delhi: Memoir of the Archaeological Survey oflndia 65.

Begley, V. 1983. Arikamedu reconsidered. American Journal of Archaeology 87:461-81.

Bellwood, P. S. 1985 Prehistory of the Indo-MalaysianArchipelago. Sydney: Academic Press.

Bhardwaj, H. C. 1979. Aspects of Ancient Indian Technology. Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass.

- ( ed.) 1987a. Archaeometry of Glass. Calcutta: Indian Ceramic Society.

-1987b. A review of archaeometric studies of Indian glasses. In Bhardwaj, H. C. (ed.) 1987a, pp.

64-75.

Brill, R H. 1987. Chemical analyses of some early Indian glasses. In Bhardwaj, H. C. (ed.) 1987a,

pp.l-25.

Bronson, B. 1977. Exchange at the upstream and downstream ends: notes towards a functional

model of the coastal state in Southeast Asia. In Mutterer, K. (ed.) Economic Exchange

and Social Interaction in Southeast Asia, pp. 39-52. Ann Arbor: Michigan Papers on

South and Southeast Asia, No.13.

- 1990. Glass and beads at Khuan Lukpad, Southern In Glover, I. C. and Glover, E.

(eds) 1990, pp. 213-29.

Bronson, B. and Glover, I. C. 1984. Archaeological mdiocarbon dates from Indonesia: a first list

Indonesia Circle 34:3744.

Bronson, B. and White, J. 1984. Radiocarbon and chronology in Southeast Asia. Unpublished

Roneo Report

Casson, L. ( ed) 1989. The Periplus Maris Erythraei. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Chin You-di 1978. Nothing is new. Muang Boran Joumal4( 4): 7-16. In Thai with English abstract

Cnob, J. 1981. The date of the symbolic coins of Burma and Thailand - a re--examination of the

evidence. Seaby Coin and Medal Bulletin 75:224-6.

to pre- and of

"""'"'"" Bulletin of zhe Indo-Pacific Prehistory Association 2:19-30.

----1983. Excavations at Ban Don Ta Phet, Kanchanatmri Province, Thailand 1980-81. .:>uuut:,u:><

Uie 1984-85

India and

(2nd revised ed.). Centre for Souiheasi .A.sian Studies,

Hull: Occasional Papers No. 16.

Glover, I.C., Charoenwongsa, P., B.AR. and K 1984. The cemetery of Ban Don

Ta Phet, Thailand: results from the 1980-81 excavation season. In B.

South Asian 1981, 319-30. Cambridge: ... ,k. ..... w ...

Glover, C. and G!.over, (eds) 1990. Southeast Asian B.AR.

International Series S-561.

Green, L.R. and Hart, F.A 1987. Colour and chemical composition in ancient glass. Journal

Archaeological Science 14: 271-82.

T. 1963. Translucent glass rings

- 19&t Monochrome beads from and elsewhere.

New analyses of excavated prehistoric glass from Bomeo.Asian Perspectives XI:125-31.

Ha Van Tan 1986. 0<: Eo: endogenous and exogenous elements. Vretnam Social Sciences

Heekeren, H. R. van 195/t The Bronze-Iron Age of Indonesia. The Martin us

Hend<eJrr,,on, J. 1988. Electron probe

91.

of mixed-alkali glasses. Archaeometry 30(1):77-

1991 Chemical characterisation of Roman vessels, enamels and tesserae. In P.B.

Vandiver, J. Druzik and E.S. Wheeler (eds), Materials Issues in Art and Archaeology

pp. 601-8. Pittsburgh: Materials Research Vol. 185.

Bo 1952a .. Examination ofscvme ancient IndE:;:m 8:17-Z'l.

1952b. m Miedieval Indiarn <reramics; some and

BeThuy. Kolliapur, Maski, Maheshwar.

lnstiew;te XIV(1):4 8-5&.

Glass technology in

1965a. Some observatioliil!! on stone and

the Malaysian Branch

of the Deccal!l College Research

l?P 44-56.

-- 1%5b. Some; glass beads from the Peninsula. LX'if;36-8.

---- 1966. A note on glass beads from the Studirz;g 8:80-94

J.R of the methods of manufacture of glass beads. In Procee.din,gs

the Fint Regional Seminar on /bicm emd Archaeology, Manila 1972,

pp.l48,glL Manila: Nati<m!llli Museum.

McKJ1mon, E.E. RR 1987. (:i;emical analyses of glasses from Sumatr:Bc.

H.C (ed.) 1987a,

Malleret,

1987. Investigation OER some Chinese

tambs. In Bhardwaj, H. (ed.) pp. 15-20.

J. 1984. A comparison between some C:istance w.stitutk>ns of the Ma!ace2

Western Pacffic. In Bayard, D. (ed.), Southreusi! Asian

.he Science pp. 235-53. University

Prehistoric Anthropology Ui.

Initial reseanch on glass making in Viem::;.m

Hoc 1983:7-54.

Vietnamesr:.} Khao Co

Peacock. B. A. V. 1979. The linter prehistory of the Malay Peninsula. In Smith, R B. and

W. (eds),Early South-East Asia, Oxforrtili: Oxford Universi1i:y Press.

Ray, H P. 1989. Early maritime oontaCIS between South and S::mmeast Asia. Journal of Southeast.

Asian

groep oorspronkelijk vandaan? Bijdmgen tot de Land- en Volkenkunde van

Nedmandsch-lndie (deel L der reeks) 50:4();9-675.

en S.N. and Chaudhuri, M. 1985. Anciens c:;lass tmd Inditll. Delhi: Indian National Science

Slnfll.a\jm2, Nik Hassan 1991. Recent research at Kua!m Pera!c. Bulletin of the Indo-Pacific

Prehistory.Associo.tion.ll:141-1S2.

Singh, R. N.1989 . .Ailu:ieF&t Indian Glass:Alrhaeologyand Technology. Demi: Parimal Fw,blications.

Solheim ll, W. G. 1981 Philippine prehistony. In Jose R.T., C'411siiio, E.S., Ellis,

and Solhemdll, W.G. (eds), Tf/ge People and An of the PhiUppines, pp. 17-83. Ln

Amie:e:les: Mmeum of Cultural History, University of California, Angeles.

EARLY SO UTI-lEAST ASIAN AND INDIAN GLASS 385

SPAFA 1987. Topics for further discussion. Appendix 8 in SPAFA Final Report of the Seminar in

Prehistory of Southeast Asia, 1W 11, Thailand, January 12-25th, 1987. Bangkok: SP AF A

Coordinating Committee.

Stern, E. M. 1987. On the glass industry of Arikamedu (Ancient Podouke). In Bhardwaj H. C. (ed.)

1987a, pp. 26-36.

Wheatley, P. 1975. Satyanrta in Suvarnadvipa: from reciprocity to redistribution in ancient

Southeast Asia. In Sabloff, J.A and Lamberg-Karlovsky, C.C. (eds), Ancient

Civilization and Trade, pp. 227-83. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press.

Wheeler, R.E.M., Ghosh, A, Deva, K 1946. Arikamedu: an Indo-Roman trading station on the

east coast ofindia. Ancient India 2: 17-124.

Wisseman Christie, J. 1982. Patterns of Trade in Western Indonesia: Ninth through Thirteenth

Centuries A.D. Ph. D. Thesis. University of London.

---- n.d. Port settlement to trading empire: genesis and growth of coastal states in maritime

Southeast Asia.

Wolters, 0. W. 1982. History, Culture and Religion in Southeast Asian Perspectives. Singapore:

Institute of Southeast Asian Studies.

Zhang Fukang 1987. Origin and development of early Chinese glasses. In Bhardwaj, H.C. (ed.)

1987a, pp.25-8.

Você também pode gostar

- Ancient Glass and IndiaDocumento6 páginasAncient Glass and IndiaSuneel KotteAinda não há avaliações

- Beads in Indonesia: Peter Francis, JRDocumento25 páginasBeads in Indonesia: Peter Francis, JRfuntraderAinda não há avaliações

- Glass Beads at Iron Age Sardis-2019Documento29 páginasGlass Beads at Iron Age Sardis-2019aivars silinsAinda não há avaliações

- 9837-Article Text-9788-1-10-20181029Documento30 páginas9837-Article Text-9788-1-10-20181029Jéssica IglésiasAinda não há avaliações

- DongSon Ken GegouDocumento3 páginasDongSon Ken GegouLourdesAinda não há avaliações

- Palavestra Amber KosovoDocumento29 páginasPalavestra Amber Kosovoaleksa8650Ainda não há avaliações

- Tom Harrisson-Bibliography of Publications Concerning Southeast Asian PrehistoryDocumento8 páginasTom Harrisson-Bibliography of Publications Concerning Southeast Asian PrehistoryjijokojawaAinda não há avaliações

- Metallurgy of Zinc, High-Tin Bronze and Gold in Indian Antiquity: Methodological Aspects (Sharada Srinivasan, 2016)Documento11 páginasMetallurgy of Zinc, High-Tin Bronze and Gold in Indian Antiquity: Methodological Aspects (Sharada Srinivasan, 2016)Srini KalyanaramanAinda não há avaliações

- Dholavira Metalwork AnnouncementDocumento115 páginasDholavira Metalwork AnnouncementVasundhara SontakkeAinda não há avaliações

- Experimental Replication of A GranulatedDocumento14 páginasExperimental Replication of A GranulatedNunzia LarosaAinda não há avaliações

- Iron Age Hillfort Survey Yields Pottery and WeaponsDocumento6 páginasIron Age Hillfort Survey Yields Pottery and WeaponsKaleVejaAinda não há avaliações

- Astragal Belts As Part of The Late Iron Age Female Costume in The South East Carpathian BasinDocumento17 páginasAstragal Belts As Part of The Late Iron Age Female Costume in The South East Carpathian BasinborkoAinda não há avaliações

- Bronze MirrorsDocumento7 páginasBronze MirrorsSweet SilendaAinda não há avaliações

- LECTURA 14. Lothrop Gold ChongoyapeDocumento20 páginasLECTURA 14. Lothrop Gold ChongoyapeADEMIR CESAR ALFONSO DIAZ ACUÑAAinda não há avaliações

- Adichanallur: A Prehistoric Mining Site: BS, S S, DV R, BR R, S B, S RDocumento26 páginasAdichanallur: A Prehistoric Mining Site: BS, S S, DV R, BR R, S B, S RThirumalai SundaramAinda não há avaliações

- Pittman and Potts 2009 Cylinder Seal DJ Nasr Abu DhabiDocumento13 páginasPittman and Potts 2009 Cylinder Seal DJ Nasr Abu DhabimenducatorAinda não há avaliações

- Treister - 2004 - Iranica AntiquaDocumento25 páginasTreister - 2004 - Iranica AntiquaMikhail TreisterAinda não há avaliações

- BEADS 27 Obluska v3Documento18 páginasBEADS 27 Obluska v3Hafud MageedAinda não há avaliações

- Medieval Copper Alloy Production and West African Bronze Analyses Part 2Documento30 páginasMedieval Copper Alloy Production and West African Bronze Analyses Part 2STAinda não há avaliações

- IRON AGE IN SOUTHEAST ASIADocumento13 páginasIRON AGE IN SOUTHEAST ASIAalkindiAinda não há avaliações

- Stone Agricultural Implements From The Island of Kos - The Evidence From Kardamaina, The Ancient Demos of Halasarna PDFDocumento13 páginasStone Agricultural Implements From The Island of Kos - The Evidence From Kardamaina, The Ancient Demos of Halasarna PDFKoKetAinda não há avaliações

- Chalcolithic Age !Documento7 páginasChalcolithic Age !Amol RajAinda não há avaliações

- A. Badescu, M. Negru, R. Avram - The Amphorae of Kapitan II Type in Dacia (RCRF Acta 38, 2003, 209-213)Documento6 páginasA. Badescu, M. Negru, R. Avram - The Amphorae of Kapitan II Type in Dacia (RCRF Acta 38, 2003, 209-213)Dragan GogicAinda não há avaliações

- Distribution of Bronze Drums of The Heger I and Pre-I Types: Temporal Changes and Historical Background (Keiji Imamura, 2010)Documento16 páginasDistribution of Bronze Drums of The Heger I and Pre-I Types: Temporal Changes and Historical Background (Keiji Imamura, 2010)Srini KalyanaramanAinda não há avaliações

- Contextualizing A Set of Classical Bronze Vessels From Macedonia - Despina IgnatiadouDocumento7 páginasContextualizing A Set of Classical Bronze Vessels From Macedonia - Despina IgnatiadouSonjce Marceva100% (1)

- Artistic Traditions p.31-47Documento17 páginasArtistic Traditions p.31-47amymeiAinda não há avaliações

- Archaeological Finds at Luke near Škrip on Brač IslandDocumento15 páginasArchaeological Finds at Luke near Škrip on Brač IslandNina Matetic PelikanAinda não há avaliações

- TamilRelations With SouthThailand and PtolemysTacolaDocumento8 páginasTamilRelations With SouthThailand and PtolemysTacolaஅசுஆ சுந்தர்Ainda não há avaliações

- Tayea Popillion - 3d Jewelry Historical Research S 2021Documento3 páginasTayea Popillion - 3d Jewelry Historical Research S 2021api-614463037Ainda não há avaliações

- A Bronze Mirror With The Titles R T-NSW M (T) - N R WT - RDocumento3 páginasA Bronze Mirror With The Titles R T-NSW M (T) - N R WT - RCeaser SaidAinda não há avaliações

- Metal Casting Traditions South Asia PT Craddock 2014Documento28 páginasMetal Casting Traditions South Asia PT Craddock 2014Srini Kalyanaraman100% (1)

- Yunnan University: School of Architecture and Planning. Dept. of Civil Engineering. Chinese Arts & Crafts AppreciationDocumento6 páginasYunnan University: School of Architecture and Planning. Dept. of Civil Engineering. Chinese Arts & Crafts Appreciationsajib ahmedAinda não há avaliações

- Early Cycladic Influence in Western Anatolia Revealed by Marble BowlsDocumento8 páginasEarly Cycladic Influence in Western Anatolia Revealed by Marble BowlsBüşra Özlem YağanAinda não há avaliações

- European Scientific Journal Vol. 9 No.1Documento20 páginasEuropean Scientific Journal Vol. 9 No.1Europe Scientific JournalAinda não há avaliações

- A Gemological Study of Turquoise in ChinaDocumento3 páginasA Gemological Study of Turquoise in China8duke8Ainda não há avaliações

- Backbone of Indus Script Corpora Tin Roa PDFDocumento228 páginasBackbone of Indus Script Corpora Tin Roa PDFTanvir KarimAinda não há avaliações

- Anderson J. Scotland in Pagan Times Bronze and Stone Ages PDFDocumento439 páginasAnderson J. Scotland in Pagan Times Bronze and Stone Ages PDFМихаил СтупкоAinda não há avaliações

- 24Documento21 páginas24ashish_upadhyayAinda não há avaliações

- The Resinous Cargo of The Java Sea WreckDocumento16 páginasThe Resinous Cargo of The Java Sea WreckLeroy EnoraAinda não há avaliações

- 1995 114 Researches and Discoveries in KentDocumento23 páginas1995 114 Researches and Discoveries in KentleongorissenAinda não há avaliações

- Beads in KonsoDocumento14 páginasBeads in KonsoashugirmaAinda não há avaliações

- This Content Downloaded From 109.92.100.174 On Thu, 30 Sep 2021 13:01:53 UTCDocumento15 páginasThis Content Downloaded From 109.92.100.174 On Thu, 30 Sep 2021 13:01:53 UTCAbram Louies HannaAinda não há avaliações

- Early Historic Stone Beads From NagardhaDocumento22 páginasEarly Historic Stone Beads From NagardhaMarekAinda não há avaliações

- Between Egypt Mesopotamia and Scandinavi PDFDocumento14 páginasBetween Egypt Mesopotamia and Scandinavi PDFLars BendixenAinda não há avaliações

- SK Eates 1991Documento15 páginasSK Eates 1991Attila Lébényi-PalkovicsAinda não há avaliações

- Journal of The Numismatic Society of IndiaDocumento306 páginasJournal of The Numismatic Society of IndiaVarun Vaidya100% (1)

- Hood - Minoan Long-Distance PDFDocumento18 páginasHood - Minoan Long-Distance PDFEnzo PitonAinda não há avaliações

- Near Eastern Jewelry A Picture PDFDocumento32 páginasNear Eastern Jewelry A Picture PDFElena CostacheAinda não há avaliações

- ChalcolithicDocumento6 páginasChalcolithicAdnan Ahmed VaraichAinda não há avaliações

- MadecouverteDocumento7 páginasMadecouverteNeperseAinda não há avaliações

- Seeing Dian Through Barbarian EyesDocumento8 páginasSeeing Dian Through Barbarian EyesQuang NguyenAinda não há avaliações

- Two New Thessalian Mints: Iolkos and PagasaiDocumento19 páginasTwo New Thessalian Mints: Iolkos and PagasaiLambros StavrogiannisAinda não há avaliações

- The SitesDocumento7 páginasThe SitesVision 12Ainda não há avaliações

- Schenk DatingHistoricalValueRoulettedWareDocumento30 páginasSchenk DatingHistoricalValueRoulettedWareCharlie HigginsAinda não há avaliações

- 2016 Sideris A Lydian Silver Amphora With Zoomorphic Handles Ondrejova Volume Studia HercyniaDocumento13 páginas2016 Sideris A Lydian Silver Amphora With Zoomorphic Handles Ondrejova Volume Studia HercyniaThanos Sideris100% (1)

- ST Teresa School English Project SESSION 2021-22: Submitted To-Babita Maam Krish Agarwal Xi A2 Roll No 12Documento13 páginasST Teresa School English Project SESSION 2021-22: Submitted To-Babita Maam Krish Agarwal Xi A2 Roll No 12krish agarwalAinda não há avaliações

- Jomon Pottery Relief DecorationDocumento9 páginasJomon Pottery Relief DecorationSidemen For LifeAinda não há avaliações

- Longshan Jade: Treasures from one of the least studied and most extraordinary neolithic jade erasNo EverandLongshan Jade: Treasures from one of the least studied and most extraordinary neolithic jade erasAinda não há avaliações

- Foote Collection o 00 Mad RDocumento280 páginasFoote Collection o 00 Mad RPriyank GuptaAinda não há avaliações

- 2 Saunders00thebarbersunhappinessDocumento20 páginas2 Saunders00thebarbersunhappinessCharlie HigginsAinda não há avaliações

- 2 Nabokov95scenesfromthelifeofadoublemonsterDocumento5 páginas2 Nabokov95scenesfromthelifeofadoublemonsterCharlie HigginsAinda não há avaliações

- 2 Horrocks06embodiedDocumento9 páginas2 Horrocks06embodiedCharlie HigginsAinda não há avaliações

- Technique of Wood Work - Some References in Ancient IndiaDocumento3 páginasTechnique of Wood Work - Some References in Ancient IndiaCharlie HigginsAinda não há avaliações

- Brouwer SouthIndianBlacksmithAndGoldsmithDocumento14 páginasBrouwer SouthIndianBlacksmithAndGoldsmithCharlie HigginsAinda não há avaliações

- 1 Englander99thetwentyseventhmanDocumento13 páginas1 Englander99thetwentyseventhmanCharlie HigginsAinda não há avaliações

- Roth LegendsOfCraftsmenInJainaLiteratureDocumento19 páginasRoth LegendsOfCraftsmenInJainaLiteratureCharlie HigginsAinda não há avaliações

- Technique of Wood Work - Some References in Ancient IndiaDocumento3 páginasTechnique of Wood Work - Some References in Ancient IndiaCharlie HigginsAinda não há avaliações

- Reade MilkingCheeseSealDocumento3 páginasReade MilkingCheeseSealCharlie HigginsAinda não há avaliações

- AcharyaPK ArchitectureOfManasaraTranslationDocumento246 páginasAcharyaPK ArchitectureOfManasaraTranslationCharlie Higgins67% (3)

- MilkingBhagavata (Fromgray)Documento1 páginaMilkingBhagavata (Fromgray)Charlie HigginsAinda não há avaliações

- Everyday Life in Babylon and AssyriaDocumento8 páginasEveryday Life in Babylon and AssyriaCharlie HigginsAinda não há avaliações

- Ergas ReligionAndBodyReclaimingMissingLinksWesternEducationDocumento12 páginasErgas ReligionAndBodyReclaimingMissingLinksWesternEducationCharlie HigginsAinda não há avaliações

- James EgyptianPaintingAndDrawingDocumento10 páginasJames EgyptianPaintingAndDrawingCharlie HigginsAinda não há avaliações

- Dellovin ACarpenter'sToolKitCentralWesternIranDocumento27 páginasDellovin ACarpenter'sToolKitCentralWesternIranCharlie HigginsAinda não há avaliações

- Waele EtchedCarnelianBeadsFromNESEArabiaDocumento10 páginasWaele EtchedCarnelianBeadsFromNESEArabiaCharlie HigginsAinda não há avaliações

- Dehejia RepresentingBodyGenderIssuesIndianArt PDFDocumento37 páginasDehejia RepresentingBodyGenderIssuesIndianArt PDFCharlie Higgins50% (2)

- Anschuetz Et Al 2001 - An Archaeology of Landscapes, Perspectives and DirectionsDocumento56 páginasAnschuetz Et Al 2001 - An Archaeology of Landscapes, Perspectives and DirectionsNagy József GáborAinda não há avaliações

- Charleston - Wheel Engraving and Cutting Some Early EquipmentDocumento18 páginasCharleston - Wheel Engraving and Cutting Some Early EquipmentCharlie HigginsAinda não há avaliações

- Calcutta School 1825Documento2 páginasCalcutta School 1825Charlie HigginsAinda não há avaliações

- Ergas ReligionAndBodyReclaimingMissingLinksWesternEducationDocumento12 páginasErgas ReligionAndBodyReclaimingMissingLinksWesternEducationCharlie HigginsAinda não há avaliações

- Brouwer SouthIndianBlacksmithAndGoldsmithDocumento14 páginasBrouwer SouthIndianBlacksmithAndGoldsmithCharlie HigginsAinda não há avaliações

- Tamil Writing 1672Documento2 páginasTamil Writing 1672Charlie HigginsAinda não há avaliações

- Possehl CambayBeadmakingDocumento5 páginasPossehl CambayBeadmakingCharlie HigginsAinda não há avaliações

- Veda Teaching FrogsDocumento4 páginasVeda Teaching FrogsCharlie HigginsAinda não há avaliações

- Ostor FilmingInNayaVillageDocumento5 páginasOstor FilmingInNayaVillageCharlie HigginsAinda não há avaliações

- Eguchi MusicAndReligionOfDiasporicIndiansInPittsburgDocumento116 páginasEguchi MusicAndReligionOfDiasporicIndiansInPittsburgCharlie HigginsAinda não há avaliações

- Ostor FilmingInNayaVillageDocumento5 páginasOstor FilmingInNayaVillageCharlie HigginsAinda não há avaliações

- Wrightetal2008 LevantDocumento35 páginasWrightetal2008 LevantVíctor M GonzálezAinda não há avaliações

- Meyer SexualLifeInAncientIndiaDocumento616 páginasMeyer SexualLifeInAncientIndiaCharlie HigginsAinda não há avaliações

- Search Inside Yourself PDFDocumento20 páginasSearch Inside Yourself PDFzeni modjo02Ainda não há avaliações

- Markle 1999 Shield VeriaDocumento37 páginasMarkle 1999 Shield VeriaMads Sondre PrøitzAinda não há avaliações

- Operational Risk Roll-OutDocumento17 páginasOperational Risk Roll-OutLee WerrellAinda não há avaliações

- UG022510 International GCSE in Business Studies 4BS0 For WebDocumento57 páginasUG022510 International GCSE in Business Studies 4BS0 For WebAnonymous 8aj9gk7GCLAinda não há avaliações

- TITLE 28 United States Code Sec. 3002Documento77 páginasTITLE 28 United States Code Sec. 3002Vincent J. Cataldi91% (11)

- Supreme Court declares Pork Barrel System unconstitutionalDocumento3 páginasSupreme Court declares Pork Barrel System unconstitutionalDom Robinson BaggayanAinda não há avaliações

- Barra de Pinos 90G 2x5 P. 2,54mm - WE 612 010 217 21Documento2 páginasBarra de Pinos 90G 2x5 P. 2,54mm - WE 612 010 217 21Conrado Almeida De OliveiraAinda não há avaliações

- MC-SUZUKI@LS 650 (F) (P) @G J K L M R@601-750cc@175Documento103 páginasMC-SUZUKI@LS 650 (F) (P) @G J K L M R@601-750cc@175Lanz Silva100% (1)

- Lesson 1 Reviewer in PmlsDocumento10 páginasLesson 1 Reviewer in PmlsCharisa Joyce AgbonAinda não há avaliações

- Chapter 12 The Incredible Story of How The Great Controversy Was Copied by White From Others, and Then She Claimed It To Be Inspired.Documento6 páginasChapter 12 The Incredible Story of How The Great Controversy Was Copied by White From Others, and Then She Claimed It To Be Inspired.Barry Lutz Sr.Ainda não há avaliações

- What Is Love? - Osho: Sat Sangha SalonDocumento7 páginasWhat Is Love? - Osho: Sat Sangha SalonMichael VladislavAinda não há avaliações

- Jaap Rousseau: Master ExtraodinaireDocumento4 páginasJaap Rousseau: Master ExtraodinaireKeithBeavonAinda não há avaliações

- Purposive Communication Module 1Documento18 páginasPurposive Communication Module 1daphne pejo100% (4)

- Art 1780280905 PDFDocumento8 páginasArt 1780280905 PDFIesna NaAinda não há avaliações

- Aladdin and the magical lampDocumento4 páginasAladdin and the magical lampMargie Roselle Opay0% (1)

- Secondary Sources Works CitedDocumento7 páginasSecondary Sources Works CitedJacquelineAinda não há avaliações

- 11th AccountancyDocumento13 páginas11th AccountancyNarendar KumarAinda não há avaliações

- PIA Project Final PDFDocumento45 páginasPIA Project Final PDFFahim UddinAinda não há avaliações

- Belonging Through A Psychoanalytic LensDocumento237 páginasBelonging Through A Psychoanalytic LensFelicity Spyder100% (1)

- The Neteru Gods Goddesses of The Grand EnneadDocumento16 páginasThe Neteru Gods Goddesses of The Grand EnneadKirk Teasley100% (1)

- Economic Impact of Tourism in Greater Palm Springs 2023 CLIENT FINALDocumento15 páginasEconomic Impact of Tourism in Greater Palm Springs 2023 CLIENT FINALJEAN MICHEL ALONZEAUAinda não há avaliações

- Golin Grammar-Texts-Dictionary (New Guinean Language)Documento225 páginasGolin Grammar-Texts-Dictionary (New Guinean Language)amoyil422Ainda não há avaliações

- McLeod Architecture or RevolutionDocumento17 páginasMcLeod Architecture or RevolutionBen Tucker100% (1)

- Icici Bank FileDocumento7 páginasIcici Bank Fileharman singhAinda não há avaliações

- Joint School Safety Report - Final ReportDocumento8 páginasJoint School Safety Report - Final ReportUSA TODAY NetworkAinda não há avaliações

- BCIC General Holiday List 2011Documento4 páginasBCIC General Holiday List 2011Srikanth DLAinda não há avaliações

- ACS Tech Manual Rev9 Vol1-TACTICS PDFDocumento186 páginasACS Tech Manual Rev9 Vol1-TACTICS PDFMihaela PecaAinda não há avaliações

- National Family Welfare ProgramDocumento24 páginasNational Family Welfare Programminnu100% (1)

- Exámenes Trinity C1 Ejemplos - Modelo Completos de Examen PDFDocumento6 páginasExámenes Trinity C1 Ejemplos - Modelo Completos de Examen PDFM AngelesAinda não há avaliações

- EE-LEC-6 - Air PollutionDocumento52 páginasEE-LEC-6 - Air PollutionVijendraAinda não há avaliações