Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

Birth Preparedness

Enviado por

Prativa DhakalDescrição original:

Título original

Direitos autorais

Formatos disponíveis

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Birth Preparedness

Enviado por

Prativa DhakalDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Birth preparedness

Definition: Birth preparedness is advance planning and preparation for delivery. Birth preparedness helps ensure that women can reach professional delivery care when labour begins and can also help reduce the delays that occur when women experience obstetric complications.

Birth Preparedness: advance planning and preparation for delivery can do much to improve maternal health outcomes. Birth preparedness helps ensure that women can reach professional delivery care when labour begins. In addition, birth preparedness can help reduce the delays that occur when women experience obstetric complications, such as recognizing the complication and deciding to seek care, reaching a facility where skilled care is available and receiving care from qualified providers at the facility.

Key elements of birth preparedness include:

Attending antenatal care at least four times: Attending antenatal care at least four times during pregnancy; Identifying a skilled provider and making a plan for reaching the facility during labour; Setting aside personal funds to cover the costs of travelling to and delivering with a skilled provider and any required supplies; Recognizing signs of complications; transport, funds, available in case of emergencies;

get to the hospital, setting aside funds; identifying person(s) to accompany to the hospital and/or to stay at home with family; and identifying a blood donor.

Because life-threatening complications can occur during the early postpartum period, birth preparedness also includes preparing/planning for accessing postpartum care during the first week after delivery and at six weeks after delivery. Birth preparedness involves not only the pregnant woman, but also her family, community and available health staff. The support and involvement of these persons can be critical in ensuring that a woman can adequately prepare for delivery and carry out a birth plan.

Birth preparedness

Evidence-based effective interventions for ANC include: Antenatal education for breast feeding; energy/ protein supplementation in women at risk for low birth weight; folic acid supplementation to all women before conception and up to 12 weeks of gestation to avoid neural tube defects in the fetus; iodine supplementation in populations with high levels of cretinism; Calcium supplementation in women at high risk of gestational hypertension and in communities with low dietary calcium intake; smoking and alcohol consumption cessation for reducing low birth weight and preterm delivery;

acupressure (sea bands) and ginger for nausea control; bran or wheat fibre supplementation for constipation; exercise in water, massages and back care classes for backache; screening for pre-eclampsia with a comprehensive strategy including an individual risk assessment at first visit, accurate blood pressure measurement, urine test for proteinuria and education on recognition of advanced pre-eclampsia symptoms; anti-D given during 72 hours postpartum to Rh-negative women who have had a Rh-positive baby; Downs syndrome screening; screening and treatment of asymptomatic bacteriuria during pregnancy; screening of hepatitis B infection for all pregnant women and delivery of hepatitis B vaccine and immunoglobulin to babies of infected mothers; screening for HIV in early pregnancy, a short course of antiretroviral drugs, and caesarean section for infected mothers at 38 weeks, to reduce vertical transmission; screening for rubella antibody in pregnant women and postpartum vaccination for those with negative antigen; screening and treatment of syphilis; routine ultrasound early in pregnancy (before 24 weeks);

external cephalic version at term (36 weeks) by skilled professionals, for women who have an uncomplicated singleton breech pregnancy; and a course of corticosteroids given to women at risk of preterm

delivery to reduce respiratory distress syndrome in the baby and neonatal mortality. Sexual intercourse and moderate aerobic exercise have been found safe during pregnancy.

Resource A: Birth Preparedness Information Needs What woman/family needs to know?

1. Expected due date: Woman needs to know expected due date and that it is only an approximate or estimated date labour may start before or after the expected due date. 2. Planning and preparation are life-saving: Woman needs to know that many obstetric complications are unpredictable and can arise suddenly and without warning. Planning or preparing for delivery does not invite such events to happen. Although it is difficult to plan for an event that will happen at an unknown date, planning and preparation can save a womans life. 3. Obstetric risks and appropriate facility for delivery: If the woman is at higher risk she needs to understand why it is crucial to deliver at a health facility

and she needs to know when she should go (e.g. before her expected due date? When labour starts?) To which facility should she go? Is there a maternity waiting home where she can stay near the facility before delivery? Even if the woman does not have serious risk factors, she still needs to be able to recognize signs of serious complications. She also needs to know that a health facility is the safest place to deliver. She needs to know which facility she should go to for delivery and whether services are available at night. 4. Basic supplies needed: The woman needs to know basic items that she should have ready for delivery, how much they may cost, and where they can be obtained. If making preparations for a baby that is not yet born is not culturally acceptable, counselling should mainly focus on items that the woman herself will need (rather than items for the baby) recommending the woman and her family amass savings to buy necessary items for the baby once it is born. 5. Facility charges for normal delivery and costs of early postpartum care: The woman needs to know what charges she can expect for a normal delivery. She also needs to know the costs associated with a caesarean section, especially if it is likely to occur given her obstetric history. 6. Available transport options and associated costs: The woman needs to know available options for reaching a facility where she can deliver her baby at

night or during the day. She needs to know the approximate travel time to the facility as well as the costs involved. 7. Total anticipated expenses: The woman needs to know the sum total that supplies, service delivery charges and transport to the facility are likely to cost so she can set aside sufficient funds. 8. Possible sources of funds: The woman needs to realistically assess whether she/her family will be able to put aside the required funds or brainstorm other possible sources of support relatives, neighbors, friends, etc. She should also know of/explore other community-level resources, such as emergency loan funds, womens groups, merry-go-rounds, etc. if they are in existence. 9. Whom to involve in birth preparations: The woman needs to know that preparing for delivery is a family responsibility and that family dialogue and discussion are essential for obtaining support and the necessary contributions. She needs to assess the roles of various family members in care-related decision-making and involve these key decision-makers in discussing the issue, as well as identify individuals who can be called upon to support her during pregnancy, delivery and the early postpartum period. 10. When to start birth preparations: Whether she is in her 2nd or her 8th month of pregnancy, the woman needs to be motivated and empowered to start

preparing for skilled care during delivery and the early postpartum period as soon as possible. Given all the preparations that need to be made, she needs to map out a realistic timeframe for making the preparation need

Você também pode gostar

- Toxemia in PregnancyDocumento21 páginasToxemia in PregnancyRiajoy Asis100% (5)

- RH Incompatibility Resource UnitDocumento6 páginasRH Incompatibility Resource UnitJannah Marie A. DimaporoAinda não há avaliações

- A Comprehensive Textbook of Midwifery and Gynecological Nursing PDFDocumento5 páginasA Comprehensive Textbook of Midwifery and Gynecological Nursing PDFrenjini100% (2)

- Maternal and Child Health IssuesDocumento12 páginasMaternal and Child Health IssuesQudrat Un NissaAinda não há avaliações

- Final Case Study SLDocumento17 páginasFinal Case Study SLCharmie Mei Paredes-RoqueAinda não há avaliações

- Rare Childbirth Emergency: Amniotic Fluid EmbolismDocumento5 páginasRare Childbirth Emergency: Amniotic Fluid EmbolismPatel AmeeAinda não há avaliações

- HIV in Mothers and ChildrenDocumento90 páginasHIV in Mothers and Childrenabubaker100% (1)

- Stages of Illness BehaviourDocumento14 páginasStages of Illness BehaviourSumit YadavAinda não há avaliações

- JSY Guidelines for Implementing India's Janani Suraksha Yojana ProgramDocumento29 páginasJSY Guidelines for Implementing India's Janani Suraksha Yojana ProgramFanyAinda não há avaliações

- A Study To Assess The Knowledge of Primi Gravida Mother Regarding Importance Colostrum at Selected Hospital Bagalkot Karnataka, IndiaDocumento10 páginasA Study To Assess The Knowledge of Primi Gravida Mother Regarding Importance Colostrum at Selected Hospital Bagalkot Karnataka, IndiaInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyAinda não há avaliações

- Breast EngorementDocumento19 páginasBreast EngorementSumit Yadav100% (1)

- History Taking in Obstetrics&gynaecologyDocumento40 páginasHistory Taking in Obstetrics&gynaecologybeamumuAinda não há avaliações

- SUCADENUMDocumento9 páginasSUCADENUMmayliaAinda não há avaliações

- IUGR: Causes, Types, Assessment and Management of Intrauterine Growth RestrictionDocumento21 páginasIUGR: Causes, Types, Assessment and Management of Intrauterine Growth Restrictionمصطفى محمدAinda não há avaliações

- Lactational AmenorrhoeaDocumento24 páginasLactational AmenorrhoeaIbrahimWagesAinda não há avaliações

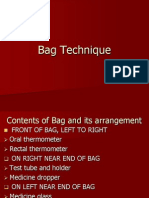

- Bag TechniqueDocumento12 páginasBag TechniquePerlie Loren Arreo CabatinganAinda não há avaliações

- Benefits of BreastfeedingDocumento20 páginasBenefits of BreastfeedingIan FordeAinda não há avaliações

- Demo AntenatalDocumento26 páginasDemo AntenatalDeepika PatidarAinda não há avaliações

- Vaginal Irrigation DemonstrationDocumento16 páginasVaginal Irrigation DemonstrationAnjali DasAinda não há avaliações

- Physiological changes postpartumDocumento14 páginasPhysiological changes postpartumXo YemAinda não há avaliações

- 03 Health Committees ReportsDocumento60 páginas03 Health Committees ReportsKailash NagarAinda não há avaliações

- Typhoid Fever 2010Documento28 páginasTyphoid Fever 2010Earl John Natividad100% (3)

- Antenatal PreparationDocumento24 páginasAntenatal PreparationSwatiAinda não há avaliações

- Indigenoussystemofmedicine 190329102338Documento27 páginasIndigenoussystemofmedicine 190329102338Shilu Mathai PappachanAinda não há avaliações

- Case Presentation On AphDocumento20 páginasCase Presentation On AphAnkita SamantaAinda não há avaliações

- Lecture-4 Diagnosis of PregnancyDocumento31 páginasLecture-4 Diagnosis of PregnancyMadhu Sudhan Pandeya100% (1)

- Unit 7 - Vesicular MoleDocumento43 páginasUnit 7 - Vesicular MoleN. Siva100% (1)

- Family Planning MethodDocumento105 páginasFamily Planning MethodKailash NagarAinda não há avaliações

- Kangaroo Mother CareDocumento9 páginasKangaroo Mother CareSREEDEVI T SURESHAinda não há avaliações

- Lesson Plan On KMCDocumento13 páginasLesson Plan On KMCriya priya100% (1)

- AbortionsDocumento99 páginasAbortionsAGERI PUSHPALATHAAinda não há avaliações

- Health Education ON Post Natal ExercisesDocumento9 páginasHealth Education ON Post Natal ExercisesAGERI PUSHPALATHAAinda não há avaliações

- Uterine AtonyDocumento20 páginasUterine AtonyKpiebakyene Sr. MercyAinda não há avaliações

- ECLAMSIADocumento14 páginasECLAMSIADrPreeti Thakur ChouhanAinda não há avaliações

- Wesleyan University Case Study on OligohydramniosDocumento8 páginasWesleyan University Case Study on OligohydramniosKinjal Vasava100% (1)

- Placenta Previa: Causes, Symptoms and TreatmentDocumento9 páginasPlacenta Previa: Causes, Symptoms and TreatmentSanket TelangAinda não há avaliações

- Postnatal Care: Samson Udho MSC, BSCDocumento34 páginasPostnatal Care: Samson Udho MSC, BSCAYO NELSON0% (1)

- Hazards of Grand Multiparity: BY DR Adefisan As Dept of Obgyn, Eksu/EksuthDocumento10 páginasHazards of Grand Multiparity: BY DR Adefisan As Dept of Obgyn, Eksu/EksuthcollinsmagAinda não há avaliações

- Intrauterine Fetal Death: College of Health SciencesDocumento49 páginasIntrauterine Fetal Death: College of Health SciencesAce TabioloAinda não há avaliações

- CP On Abrutio PlacentaDocumento13 páginasCP On Abrutio PlacentaUsha DeviAinda não há avaliações

- CVS Procedure ExplainedDocumento5 páginasCVS Procedure ExplainedpriyankaAinda não há avaliações

- Abnormal Delivery Types and ManagementDocumento12 páginasAbnormal Delivery Types and ManagementBadrul MunirAinda não há avaliações

- Baby Agnes Samuel NBU Care PlanDocumento4 páginasBaby Agnes Samuel NBU Care PlanMuhammadAinda não há avaliações

- All India Institute of Medical Sciences, Jodhpur College of NursingDocumento17 páginasAll India Institute of Medical Sciences, Jodhpur College of NursingFarheen khanAinda não há avaliações

- Demonstration POSTNATAL EXAMINATION Easy WayDocumento9 páginasDemonstration POSTNATAL EXAMINATION Easy Wayjyoti singhAinda não há avaliações

- Hypothermia in NeonatesDocumento7 páginasHypothermia in NeonatesBhawna Pandhu100% (2)

- Course Title:-Child Health Nursing Topic: - Care of Newborn Duration: - 1 HR Venue: - Classroom A.V.Aids: - Ppts Date: - General Objectives: - Specific ObjectivesDocumento9 páginasCourse Title:-Child Health Nursing Topic: - Care of Newborn Duration: - 1 HR Venue: - Classroom A.V.Aids: - Ppts Date: - General Objectives: - Specific ObjectivesBhawna Pandhu100% (1)

- Perineal Care: Our Lady of Fatima UniversityDocumento3 páginasPerineal Care: Our Lady of Fatima University3s- ALINEA AERON LANCE100% (1)

- Florence College of Nursing Medical Surgical Nursing: Health Talk ONDocumento13 páginasFlorence College of Nursing Medical Surgical Nursing: Health Talk ONSunil Kumar100% (1)

- Antenatal Exercise BenefitsDocumento10 páginasAntenatal Exercise BenefitsAGERI PUSHPALATHAAinda não há avaliações

- INTRODUCTIONDocumento5 páginasINTRODUCTIONDrDeepak PawarAinda não há avaliações

- Gynaecology & Obstetrics Dept. OPD & Wards: PGDHM & HC, Sem:1 Roll No.2, DR - Vaishali GondaneDocumento23 páginasGynaecology & Obstetrics Dept. OPD & Wards: PGDHM & HC, Sem:1 Roll No.2, DR - Vaishali GondaneRachana VishwajeetAinda não há avaliações

- Postnatal CareDocumento34 páginasPostnatal CareApin PokhrelAinda não há avaliações

- BREAST SELF EXA-WPS OfficeDocumento16 páginasBREAST SELF EXA-WPS OfficeEra khanAinda não há avaliações

- Anaemia in Pregnancy: WelcomeDocumento25 páginasAnaemia in Pregnancy: WelcomeDelphy VargheseAinda não há avaliações

- Newborn Assessment FinalDocumento63 páginasNewborn Assessment FinalsanthiyasandyAinda não há avaliações

- Antenatal PreparationDocumento47 páginasAntenatal PreparationVijith.V.kumarAinda não há avaliações

- Antenatal Care & ManagementDocumento23 páginasAntenatal Care & ManagementPabhat Kumar100% (1)

- Global Safe Motherhood Agenda: Reducing Maternal MortalityDocumento41 páginasGlobal Safe Motherhood Agenda: Reducing Maternal MortalityRubinadahalAinda não há avaliações

- High Pressure Check Valves 150119Documento6 páginasHigh Pressure Check Valves 150119Nilesh MistryAinda não há avaliações

- 5th Gen Vocational Model GuideDocumento34 páginas5th Gen Vocational Model GuideKieran Ryan100% (1)

- Business Environment Notes For MbaDocumento34 páginasBusiness Environment Notes For Mbaamrit100% (1)

- Peplink Balance v6.1.2 User ManualDocumento258 páginasPeplink Balance v6.1.2 User ManualoscarledesmaAinda não há avaliações

- Olivier Clement - Persons in Communion (Excerpt From On Human Being)Documento7 páginasOlivier Clement - Persons in Communion (Excerpt From On Human Being)vladnmaziluAinda não há avaliações

- Osce Top TipsDocumento20 páginasOsce Top TipsNeace Dee FacunAinda não há avaliações

- Mrs Jenny obstetric historyDocumento3 páginasMrs Jenny obstetric historyDwi AnggoroAinda não há avaliações

- Answer Following Questions: TH THDocumento5 páginasAnswer Following Questions: TH THravi3754Ainda não há avaliações

- Acc6475 2721Documento4 páginasAcc6475 2721pak manAinda não há avaliações

- Spec 120knDocumento2 páginasSpec 120knanindya19879479Ainda não há avaliações

- Summary of Jordan Peterson's Biblical LecturesDocumento25 páginasSummary of Jordan Peterson's Biblical LecturesRufus_DinaricusAinda não há avaliações

- Electromagnetic Spectrum 1 QP PDFDocumento13 páginasElectromagnetic Spectrum 1 QP PDFWai HponeAinda não há avaliações

- 390D L Excavator WAP00001-UP (MACHINE) POWERED BY C18 Engine (SEBP5236 - 43) - Sistemas y ComponentesDocumento3 páginas390D L Excavator WAP00001-UP (MACHINE) POWERED BY C18 Engine (SEBP5236 - 43) - Sistemas y ComponentesJuan Pablo Virreyra TriguerosAinda não há avaliações

- Sports Project BbaDocumento10 páginasSports Project Bbadonboy004Ainda não há avaliações

- Economic Impact of Food Culture and History of West Bengal On TouristDocumento17 páginasEconomic Impact of Food Culture and History of West Bengal On Touristhitesh mendirattaAinda não há avaliações

- European Summary Report On CHP Support SchemesDocumento33 páginasEuropean Summary Report On CHP Support SchemesioanitescumihaiAinda não há avaliações

- Manual Videoporteiro Tuya Painel de Chamada 84218Documento6 páginasManual Videoporteiro Tuya Painel de Chamada 84218JGC CoimbraAinda não há avaliações

- 3 Strategic CapabilitiesDocumento20 páginas3 Strategic CapabilitiesMariyam HamdhaAinda não há avaliações

- TOJan Feb 16Documento40 páginasTOJan Feb 16kumararajAinda não há avaliações

- Programmable Logic Controller (PLC)Documento19 páginasProgrammable Logic Controller (PLC)Jason Sonido88% (8)

- Radio Data Reference Book Jessop 1967Documento148 páginasRadio Data Reference Book Jessop 1967Cubelinho ResuaAinda não há avaliações

- Mind Your Manners ReadingDocumento58 páginasMind Your Manners ReadingВероника БаскаковаAinda não há avaliações

- Environment - Parallel Session - Jo Rowena GarciaDocumento26 páginasEnvironment - Parallel Session - Jo Rowena GarciaAsian Development Bank ConferencesAinda não há avaliações

- The Demands of Society From The Teacher As A PersonDocumento2 páginasThe Demands of Society From The Teacher As A PersonKyle Ezra Doman100% (1)

- English Romanticism: Romantic PoetryDocumento58 páginasEnglish Romanticism: Romantic PoetryKhushnood Ali100% (1)

- Kriging: Fitting A Variogram ModelDocumento3 páginasKriging: Fitting A Variogram ModelAwal SyahraniAinda não há avaliações

- Law Movie Analysis Erin BrockovichDocumento3 páginasLaw Movie Analysis Erin Brockovichshaju0% (3)

- Python Programming For Beginners 2 Books in 1 B0B7QPFY8KDocumento243 páginasPython Programming For Beginners 2 Books in 1 B0B7QPFY8KVaradaraju ThirunavukkarasanAinda não há avaliações

- Miguel Angel Quimbay TinjacaDocumento9 páginasMiguel Angel Quimbay TinjacaLaura LombanaAinda não há avaliações

- Specification Table for Kindergarten English Cognitive Domain LevelsDocumento2 páginasSpecification Table for Kindergarten English Cognitive Domain LevelsStefany Jane PascualAinda não há avaliações